Link

0 notes

Photo

C-32 Sucursal: La Ene at MALBA Buenos Aires, Argentina August 8 - October 13, 2014

Do It Yourself

Every exhibition is a proposition. Every museum is a project.

La Ene, the Nuevo Museo Energía de arte contemporáneo, was founded in August 2010 as a critique of the institutional system and the ways that art is circulated, legitimized and produced. The first contemporary art museum in the city of Buenos Aires, La Ene is a critical intervention on its environment, a way of building formats that renew the ways we think of museums. it sets out to question the supposed opposition between the alternative and the institutional. it furthers experimentation and critical thinking on art. it is an open, flexible, dynamic, expansive, and chévere museum.

La Ene is an institution that responds to the needs of a specific environment. it exists because there is a community that demands it not because of a preexisting collection in need of a shelter or someone to administrate it. The nuevo Museo is a tool that combats the use of art for the sake of the mainstream, and the banalization and corporate globalization of museum as trademark. La Ene is based on a “do-it-yourself” philosophy and the new museology; it is a dynamic and amorphous, inclusive and provocative organism. it is a space of cooperation, communication, and encounter, a host of alternative practices in research and cultural production.

A project like La Ene partakes of two distinct genealogies, one that reacts to local concerns and another involving the broader history of institutional criticism. The first critical institutions emerged in other continents in the sixties (like the Moderna Museet in Stockholm or El Museo del barrio in New York). For too long, in Buenos Aires the discourse on art and the production of many young artists have necessarily been enmeshed with commercial galleries. Even today, despite the vast number of independent, artist-run projects in Argentina, the gallery is still the dominant aspirational model. In lack of institutions or government structures that respond to updated policies, or proper funding to further contemporary art practices and the working conditions of cultural agents, La Ene must exist. The museum produces exhibitions by local and international artists and curators conceived specifically for its space. It organizes educational events—seminars, workshops, lectures, informal gatherings—that encourage new readings of art history and artistic practices. It has established a network of dialogue between independent projects in Latin America and the rest of the world in order to support artists and to foster an exchange of exhibitions, materials, and ideas. The institution came first, then came the collection. For La Ene, the creation of a collection is not an instance of legitimation, but rather a statement on what can be considered a collection and how it can be built. if, in its founding, La Ene signaled an institutional void, its collection is similarly critical of the way local museums acquire, conserve and put art in circulation—or fail to do so. The museum’s collection is stored on a hard drive. what La Ene holds in its collection are not objects, but the rights, granted by the artists, to reproduce works. it is a hybrid set of works that combines traditional notions of collection and archive with features of information technology. The origin of this collection lies in an analysis of the difficulties that a museum faces in attempting to have a collection, difficulties linked to the conservation and storage of its contents. In La Ene’s new museum format, the collection can be transported and installed anywhere. Its works can be reproduced according to the space they occupy: some works exist in memory, others are printed out, remade, or simply planned. a pixel is a pixel, regardless of location. a memory expands beyond the confines of a building. For the exhibition Sucursal, La Ene temporarily moves its seat to MALBA. The show mostly consists of a display of La Ene’s collection and of archival material pertinent to the activities it has organized since its founding four years ago. in the framework of the exhibition, Radamés “Juni” Figueroa, from puerto Rico, and Sofía Olascoaga, from Mexico, will carry out specific projects as part of their residencies at La Ene. Lastly, Luis Camnitzer’s work El museo es una escuela [The Museum is a School], which partakes of La Ene’s ideology regarding the social role of the museum, will be exhibited on MALBA’s façade. La Ene is not an answer, but many questions. How to have a collection without storage space? How to be political without engaging in proselytizing? How to be a critical and self-reflexive institution? How to build a collection on the basis of physical limitations and the possibilities of memory? This new Museum promotes acting outside of established institutions in order to create our own, proposing ideas even when they seem to fall on deaf ears. La Ene will be a success if it outlives us, if it ceases to be necessary, or if it finally stops being ad honorem, not necessarily in that order.

#la ene#museo la ene#luis camnitzer#MALBA#radamés figueroa#juni figueroa#sofia olascoaga#gala berger#santiago villanueva#sofía dourron#marina reyes franco

0 notes

Photo

Trabaja por tu nombre [Work for your name]

Tobías Dirty

Urgente, August 2014

Criminal Queer

A choir of transvestite fairy godmothers repeats phrases like edicts: "work for your name even if it's false," "manage time and do not waste your will," "work on behalf of everyone, even if you're weird, clumsy and silly." Alternating between a tone of reprimand and almost indifferent recommendation, the chorus repeats itself to exasperation. Tobias Dirty, Toto Dirty, Tobias García -all and one- trabaja por su nombre [”works for his name”] in an exhibition that reflects on his biography, linking artistic work to the construction of identity and the relationship between desire and commitment.

The Protestant ethic of work runs through the room like a ghost of a past adolescence raking the leaves in the patio of the family home. Historically, the belief that hard work leads to success also goes hand in hand with prejudice and discriminatory policies. You have to earn a place in the world, deserve things and affection, recognition and the right to be who you feel you are. It is no coincidence that among the synonyms of work are burden, grief, martyrdom, torment, battle and struggle. How can he be less García and more Dirty? Far from the aspirations of Christian salvation, the references to work that abound in this exhibition reflect on the relationship between the expectation of struggle and homonegativity.

The pieces that make up the exhibition are hybrid works that are presented as crosses between drawing, installation, sculpture, performance and sound art - contemporary art as a hermaphrodite entity. For Dirty, the human body is a sculpture and the clothes, shoes and accessories that complement it are essential for the construction of being. "Work is a private choice and a public task," says the chorus. Trabaja por tu nombre relates to both the "personal politics" of feminist theory, to what he has in common with other boys who also raked their backyards, to a playlist that goes from Missy's Work It to Iggy's Work, and the development of his work as an artist.

Now get this work

Now get this work

Now get this work

Now get this work

Working on my shit

Performance materials:

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A thousand pieces

Luciana Rondolini and Nicolás Vasen

Recoleta Cultural Center, Buenos Aires

May 8 to 29, 2014

Something is rotten in the state of Denmark. Shortly before midnight, Hamlet, Horatio and Marcellus converse among the castle's protective battlements. While they wait in the dark, they hear other men in the palace laughing and dancing drunkenly; the country is the laughingstock of Europe. The ghost of the father of Hamlet, assassinated by the present king, makes his appearance and Hamlet leaves with him in spite of the pleadings of his friends. Marcellus, enraged by the evident moral and political corruption of his country, pronounces one of the most famous lines of English literature: "Something is rotten in the state of Denmark." Horatio prefers to trust that the divine will will save everything, but Marcelo -wisely- knows it cannot happen.

The tensions between construction, durability and false image are the basis of this joint exhibition by Nicolás Vasen and Luciana Rondolini. Working in sculpture, drawing, photo and installation with very different sensibilities, the works of Vasen and Rondolini converge in their approach to the Recoleta Cultural Center’s own building as a fragile container of meanings. Vasen’s structures inhabit Rondolini’s decorated space in a counterpoint of works that approach opposite concepts that stem from architecture and construction: tension and resistance, matrix and decoration, decadence and ostentation.

Appearance and reality. The awkward truth is covered in an apparent pleasantness that requires a closer look. Matter is resistant to change but at the end of the day it is still malleable, revealing its inner layers and mechanisms. These forms echo the ideas and conversations that occur in this old convent. The palace intrigues are not far from the internal tensions of an art exhibition. We follow the ghost of Hamlet's father into darkness because we know that there is no divine will that changes this state of art.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Donde hay protesta hay negocio

Ricardo Alcaide, Gala Berger, Carolina Caycedo, Marcelo Cidade, Livia Corona and Guillermo E. Rodríguez

Galería Agustina Ferreyra, San Juan

“So you tell me what I have to do; I will show you the budget, I’ll tell you the price you can ask for the apartments in a house like the one we can build here, in a narrow, sunless spot; I’ll explain everything and you’ll tell me how much I can profit off it, or I stand to lose money; I’ll conform to whatever you tell me...”

- Caisotti, in La especulación inmobiliaria by Italo Calvino

The last decade has seen the rise of a series of institutionalized left-leaning governments throughout Latin America, as well as a strong bid for power by longstanding interest groups. Venezuela, Bolivia, Brazil and Argentina became the countries that challenged the "empire" the most, either by their rhetoric or by their renewed economic power. In several countries, however, the economic policies from the nineties have deepened. Even more interesting are the contradictions between discourse and actions that have arisen during this economic boom period in most of Latin America. Puerto Rico, from its own relative historical isolation in relation to the rest of the region, reblogs, retweets, criticizes and idealizes the rest of the continent from its own deep economic and social crisis. We know a thing or two about economic bubbles, the meddling of financial groups, real estate speculation, ecologic devastation and middle class aspirations.

This exhibition reflects, without Manichean pretensions, on the rapid economic growth and social conflicts that it produces, provokes and represses. Through a selection of their works, Ricardo Alcaide, Gala Berger, Carolina Caycedo, Marcelo Cidade, Livia Corona and Guillermo E. Rodríguez address social and economic processes in several Latin American countries at different times in their history, such as commentary on the failures of mid-twentieth century modernist ideals, the obsolescence of several national currencies and the pantheon of figures it ennobled, to the repression of those who combat the speculation with natural resources.

Marcelo Cidade’s Luto e Luta serves as an anchor for this show, which was originally conceived during the several weeks of protests in cities across Brazil following the increase of twenty cents to public transportation in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The sculpture consists of a Brazilian flag buried underneath 240 cement blocks. A critique of the developmental dream of the fifties, Cidade tries to contradict the concept of identity construction with a formal aspect that evokes a kind of tomb. Similarly, Ricardo Alcaide -Venezuelan but a resident of São Paulo- is equally influenced by modern architecture and the aspirations of the burgeoning petrodollars in seventies Venezuela. The pictures from his Prototypes series consist of arrangements of found objects presented by way of modernist buildings, which in turn appear to be housing prototypes for the many people -in São Paulo or any other city- who, wrapped in some blanket, spend their nights on the streets. In her Two Million Homes for Mexico series, Livia Corona also takes as a starting point architecture, urban planning, the construction business and the speculation surrounding it. In 2000, then presidential candidate Vicente Fox Quesada proposed a six year plan to build two million houses for low-income people, mostly families who aspire to a middle-class life by moving closer to larger cities. In one of the photos, a child resident of one of these developments, watches us from his humble neighborhood playground. Built in areas with little or no urban planning, little living space and poor materials, these houses make us question their status as homes. In her work, Corona explores the social, cultural and ecological transformation that occurs as a product of speculation, campaign promises and the literal sale of dreams.

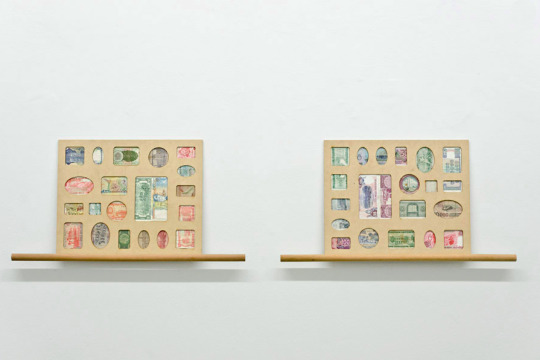

The relationship between graphics, history, memory and object is very present in the works of Gala Berger and Guillermo E. Rodriguez. Berger’s constructions from La piedra que cambió las cosas series, made from wood and uncirculated banknotes from various countries, seem to be part of an old photo album. These currencies from Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, United States, Bolivia and Brazil may be more valuable to collectors than have any actual market value. The bills feature a careful selection of buildings, historical figures, national landscapes and dated heroic deeds. This kind of portrait of the national character of the people is as changeable as the stock market, the interests of the World Bank and the fall of the dictatorships that once plagued the continent. Now there is a National Institute of Argentine Historical Revisionism and in recent years, Argentine bills have become, even more because of their novelty, in an ideological object: in the hundred peso bill, Julio Roca was replaced by Eva Perón and now, instead of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, the fifty peso bill reclaims the Malvinas [otherwise known as the Falkland] Islands for Argentina. Palimpsestos are a series of works by Guillermo E. Rodríguez which take their individual title from the numbers featured in the lottery tickets that cover the entire surface of each stretched canvas. Rodríguez’ pieces play with references to painting, but also reflect on the images that are printed on each lottery ticket and the kind of luck that a losing ticket implies. Palimpsest is word that derives from the greek for “scraped clean and used again”. In geological terms, palimpsest are geographic features made up of superimposed structures created at different times. Just as Rodríguez reuses and adds layers of meaning to the unfortunate lottery tickets, in times of scarcity, manuscripts were erased for re-use. The graphics that accompany these numbers allude to the reverence for the mother, festivals in various towns of the island and historical monuments, as a reminder of what is truly important in terms of traditions, culture and family.

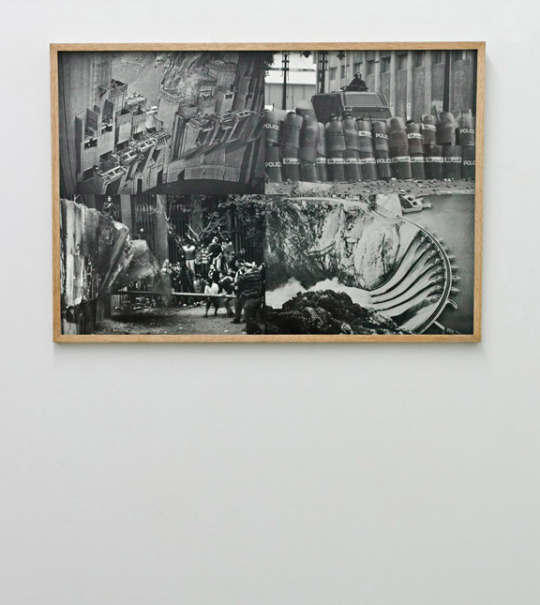

Several images of protests in Tahrir Square in Cairo and Swedish dams make up Carolina Caycedo’s Escalated River. This picture is just a sample of a larger project called Be Damned, which delves into the concepts of flow and containment. Caycedo explores water as a repressive element, while simultaneously being suppressed, deviated and polluted. Water is used for both crop irrigation and for the construction of dams, being of particular interest the ones recently built in Colombia and Brazil. The sinister implications range from the use of water cannons for crowd dispersion, to the neocolonial reality of dams being built by foreign multinational companies that ipso facto take control of rivers. The pun between represa and represión [dam and repression] or in the project’s own title, are in themselves comments on the uses and abuses of water as a catalyst for social change, violence and population control. As the old saying goes, el río tiene memoria [the river remembers].

The title, Donde hay protesta hay negocio [Where there’s protest there’s business], suggests we thinking about how the economy works today, in which every unjust act is accompanied by someone who profited from it. However, it also seeks to plant a doubt about our own contradictory roles, especially when politically motivated art is produced. With a selection of works by artists from Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, Brasil, México and Puerto Rico, the exhibition presents a b-side to the rapid economic development in Latin America and the battles fought along the way.

0 notes

Photo

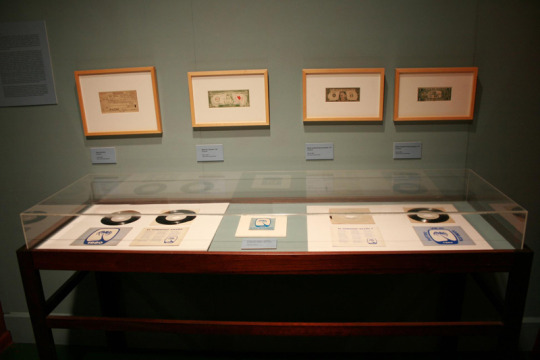

Museum Ad Nauseam: Essays in institutional critique

La Ene - Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo

Felipe Ehrenberg (MX)

Nicolás Robbio (AR)

Mónica Rodríguez Medina (PR)

+

Contributions by: Richard Kostelanetz, Pablo León de la Barra, Julieta González, 100 Propuestas para un nuevo museo, Centro de Información y Documentación Nacional de las Artes Plásticas en la Galería de Arte Nacional de Venezuela, The Joker and Prince.

November 8 to December 6, 2013

Complain and create

In June 2012, a group calling itself Organized Artists issued a declaration of rejection of the acquisition policy of the Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires, a city museum. The system of massive donations that had been imposed during the 2001 crisis was being revived, even in very different economic and social conditions, more than 10 years later. The exhibition to be held, Últimas Tendencias II [Latest Tendencies II], without any other curatorial criteria than the extortive mechanism of donation in exchange for inclusion, represents only a symptom of the great budgetary, ideological and ethical problems of public museums in Buenos Aires. In order to contextualize the struggles, claims and possible creative alternatives to the institutional crisis that was made visible in 2012, Museum Ad Nauseam: essays in institutional criticism presents a series of works, documents, research and, why not, a video of the Joker destroying works of art in the Gotham City museum to the rhythm of Prince's music.

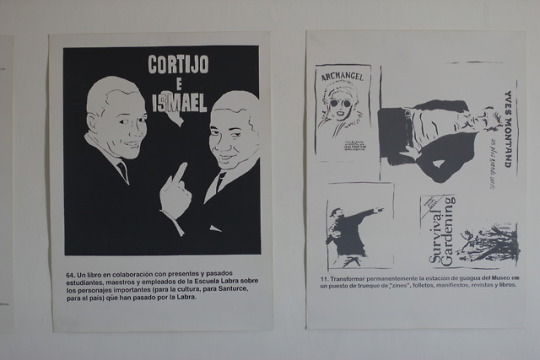

The exhibition is divided into two units, the ground floor covers criticisms and interventions, and a second section in the mezzanine with creative proposals and alternative institutions. The vitrine displays the work that inspires the title of the exhibition, Museum Ad Nauseum (1970), a visual poem by Richard Kostelanetz. Critical works include a photo, a transcription translated into Spanish and original audio of the famous A Date With Fate at The Tate (1970) by the Mexican artist Felipe Ehrenberg. With his face covered except for a slit to see through one eye, Ehrenberg went to the Tate Gallery in London and, in a heated discussion after being banned from entering the museum for his clothing, intermittently declares himself a Work of Art and a Human being. The discussion is interesting because of the various issues it raises: from which person can enter the building, to what is called a work of art and who has the right to do so within the institutional framework of a museum. For her part, Mónica Rodríguez presents a chronology of protests and interventions by various groups of artists in New York City from the thirties to the present. These informational panels highlight the continuous claims for practically the same things over several decades: representation of minorities within institutions, ethics and transparency with respect to posts and economic resources, as well as - increasingly - demands for labor dignity a the recognition of artists as cultural workers. This chronology is accompanied by some "scores" that, evoking the Fluxus events, indicate how to carry out brief performances in which fragments of past protests are recreated.

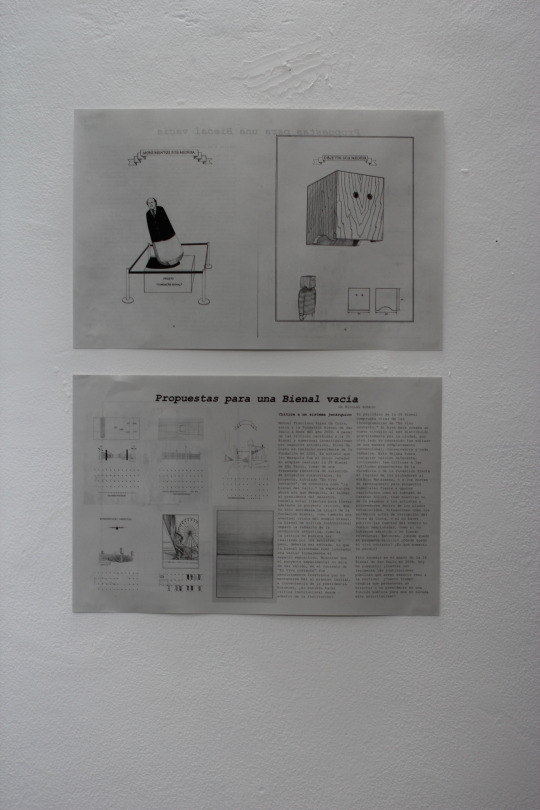

Sometimes the most venerated institutions are not museums, but biennials, and these are not exempt from controversies, as evidenced by the work of Nicolás Robbio. Proposals for an empty Biennial, by Nicolás Robbio, is a newspaper publication of 8 drawings and a critical text to the Bienal de São Paulo 2008 entitled "Critique of a hierarchical system". It is the first time that all the drawings are published after several were censored in the publication of the biennial for which they were commissioned.

The proposals section includes a series of posters and documents that record situations of institutional tension and the actions in response of artists and other actors of the cultural scene. The poster for the Novo Museo Tropical, a museum without walls designed by the Mexican curator Pablo León de la Barra, presents an alternative historiographical proposal on the tropical, as Ad Reinhardt once did with modern art, only through a bunch of bananas. For comparison, another discrepancy between museum and art scene is featured in the exhibition. In 2008, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Puerto Rico requested support from the artistic community to ask the government for more operating funds, but the artists and other cultural workers responded by demanding more control over the institution. The open letter replying to the museum’s request is included in the exhibition, as well as several posters related to the 100 proposals for a new museum that stemmed from the ensuing public discussion, designed by Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Michy Marxuach and Tony Cruz, in collaboration with Abdiel Segarra, Rafael Miranda, Conboca, Repuesto and others. The debate that took place around the museum’s budgetary issues culminated in the resignation of the director, but the other demands were not met. In order to continue the research proposed by the exhibition, the show features an open archive and a reference library.

These works and events serve as a point of reference for the recently reactivated proactive attitude of a sector of the Buenos Aires art scene, who are not willing for changes to be dictated by others or, worse, for nothing to change.

Nicolás Robbio

Felipe Ehrenberg

#mónica rodríguez medina#nicolás robbio#Felipe Ehrenberg#Pablo león de la barra#novo museu tropical#Richard Kostelanetz

0 notes

Photo

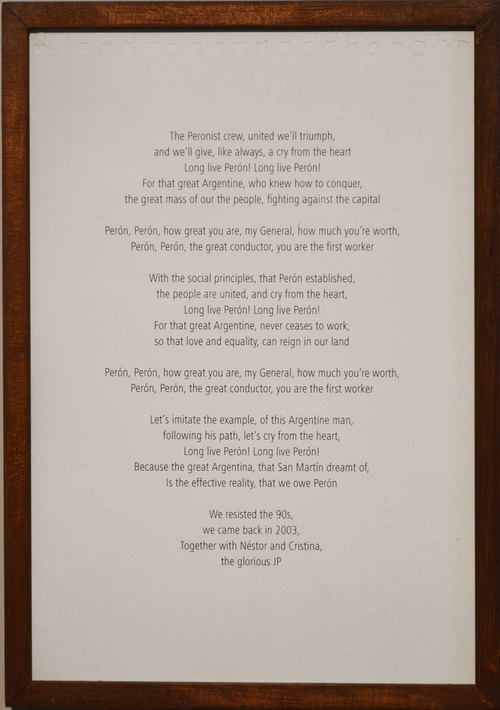

What would be a conversation between an old Peronist and a young militant of La Campora be like? What space do the visual arts have within the “national model”? What does redistribution imply, not only in economic but also in cultural terms? How did you find out that I'm from the middle class? These and other questions - implicitly and explicitly - are posed by Nani Lamarque in his exhibition Frente en Alto.

This exhibition is a rumination, from the visual arts, on the "gained decade” of Kirchnerist politics and the terrain that it conquered among the youth. When we refer to politics and militancy in art, the questioning of the space contemporary art has in state policies is implicit. These ambiguously militant works comprise a selection of two years of Lamarque's production, whose strength resides precisely in his obstinacy in not assuming a clear position. His works bounce off the ideas of those who look at them.

The exhibition itself is simple, concise. A meter and a half of light blue synthetic enamel protects the walls and gives, literally, an air of asphyxiating institutionality. A charcoal drawing guiltily questioning the artist’s social class dominates the room. In a niche there is a picture of the stain left by a cross when it was removed from the wall. I can not help but think about when President Néstor Kirchner gave the order to Lieutenant General Bendini to withdraw the paintings of Videla and Bignone. The spectrum of the cross is still there, the grime persists. Customs are hard to forget and history is never erased. An English translation of a song by La Cámpora and three t-shirts conclude the display. The apparent contradiction of using the language of the American Empire is taken by Lamarque as a symbol of a past time in which they talked about "exporting the model", something like a neo-pedagogical colonization in reverse. Just two years ago the Occupy movement talked about taking factories and making cacerolazos of their own. Finally, the shirts that are raised as flags are the clearest representation of the understanding of popular culture and politics. It is about the game of seduction of the images of immortality, the political slogans and the renamed Néstornauta.

The contradictions of Argentina are never as obvious as in the use and abuse of images for political purposes. However, if something is evident it is that it has been during the last 10 years that a space has been gained for historically marginalized groups and communities. It is in this framework that Lamarque asks about the place of art.

For La Ene, as a project of institutional critique in the field of contemporary art and host of this exhibition, it is very important to discuss artistic practice in relation to politics. The decision to present an exhibition that speaks explicitly about political parties and militant groups aims to highlight the curious imbalance that exists in relation to political positions and the art scene in Buenos Aires. At a minimum, we must be militants in our own field.

#nani lamarque#marina reyes franco#la ene#museo la ene#argentine art#cristina fernández de kirchner#néstor kirchner

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wordings

Gala Berger

The Wooden Floor, Santa Ana, California

Sayago & Pardon Collection

June 2013 - June 2014

In the preface to a translation of Balzac ́s novel Father Goriot, the famous Chinese translator Fu lei writes: “in terms of effect, translating is supposed to be like painting. What is sought is not formal resemblance, but spiritual resemblance.”1 Fu lei was the only independent translator in China during the 50s and 60s, the decades immediately following the Communist revolution.2 Educated in France, he worked, since his return to China in the 30s, as a professor of Art History and French at the Academy of Fine Arts in Shanghai, where he also edited its art magazine. Most of his translations were from French to Chinese, although he also translated a volume on British painting from English. Fu understood Western languages as analytic and prose-like, while Chinese was synthetic and poetry-like. According to Fu, the ideal translation would be the original author’s writing in Chinese. This, of course, is impossible because a foreigner could never become Chinese.3

Three years ago, Gala Berger met lin-Yi Hsuan, a young Taiwanese artist who had just moved to Argentina. The drawings that Berger developed afterwards would become the series Chino para principiantes [Chinese for Beginners], a jokingly self imposed bet, a ridiculous quest to learn Chinese. The drawings—as much as 300 of them—are playful and abstract yet also tell a story of migration, translation, diplomatic issues and language. The 88 works that make up this exhibition are part of a larger bid at grasping the Chinese language—so visual, poetic, conceptual—through her own art. With Mao Bianzhi paper, a tool used at Chinese schools to teach traditional calligraphy, Berger attempts an intuitive approach to language. Gala Berger paints, but not in the sense that a lot of Argentine artists do, often reflecting on the country’s own art history or referring to painting itself. She uses it as a way to interact with other cultures, nature itself, or as a means to experiment with economies or disregard the conventions of business in art. Her artistic projects take as much from the immaterial world of the internet as from the materials she chooses to use. This results in a sort of open source process and value system in which she gives as much as she takes, always giving credit and modifying ideas for the local context. Underscoring this attitude is the fact that Berger seldom works alone. While it’s true that, as an artist, she still maintains a studio, her projects and exhibitions are not for mere contemplation. Berger’s artistic practice is expansive, taking on the form of various ventures, both as an artist and organizer, often blurring the lines between one and the other. Following a 2009 residency in the Korean city of Anyang-si, Berger became involved with Munguau, a cultural exchange project between South Korea and Argentina, both as co-director and curator. Through a wide range of activities, from parties to workshops and art exhibitions both in Argentina and abroad, Munguau seeks to expand the involvement and awareness of the Korean community in Argentina, which has been growing since the 1960s. Beyond the successive displacements of Koreans to Argentina, the project focuses on the latest generation of Argentine-Koreans, arising from an interest in cultural exchange, not only between Argentina and the Korean peninsula, but with members of the Korean community in Buenos Aires. Born out of the sheer will of a group of people, this project provides a much needed active cultural dialogue between these two countries, often bypassing the obsolete diplomatic institutions. A kind of “do-it-yourself”, although not entirely by yourself, attitude permeates most of Berger’s projects. during part of 2009 and 2010, Berger, along with fellow artists osías Yanov and Paola Vega, developed their own teas and organized gatherings in a tea house they rented and fixed up. referencing Gordon Matta-Clark and Food, the restaurant he co-founded in new York in 1971, Energía Casa de Té was a tea house where the artists offered their own herbal concoctions, but also served as a meeting place in a still desolate-looking girls school turned into a commercial gallery and increasingly an aspiring artistic space. That very same space would later become la Ene, or nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo, an experimental museum that is in itself an institutional critique project.4 Somewhat later in 2012, Berger also embarked on founding and co-directing Galería inmigrante together with fellow artists Cotelito and Mario Scorzelli. With no gallery in which to show their work, the artists made-up their own and invited along other friends. in a country lacking a strong art market, this is not uncommon. However, Berger doesn’t confine herself to the role of administrator, rather she creates artworks around the ideas of these small institutions she has helped co-found. in this vein, she has exhibited a set of photographs about making your own gallery, a video explaining how to replicate la Ene’s model for creating a museum, and placed a street sign advertising la Ene right across the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires. Whether it’s founding a tea house as an art project, an artist-run-gallery or the first—and smallest— contemporary art museum in the city, there is always an element of disregard towards established institutions but also a reverence and homage to certain key influences in Berger’s work. in the same spirit of paying tribute to her personal and art historical references, such as the Bauhaus school and the Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño, Berger presents us with Vorkurs, Denkraum and Todos los tiempos confluyen [All Times Converge], three subsets from the “Chino para principiantes” series, consisting of 88 drawings and watercolors on Chinese rice paper. The works themselves are mostly abstract, some highlighting the orange squares and triangles that are supposed to guide the students when writing the characters, while others completely obscure them, or reference the brush strokes found in traditional Chinese calligraphy and landscape painting. developed between 2010 and 2012, these works represent Berger’s interest in creating an intuitive learning system concerning language. Vorkurs is the name of a fundamental class in the Bauhaus school, taught by Johannes itten. Concerned with researching the main components of visual language, such as texture, color, shape, contour and materials, the class also emphasized the role of intuition through abstraction, which led to a break from the institution. on the other hand, Denkraum is a term used by Aby Warburg to describe a state of consciousness pervaded by reason. like itten, Warburg also stressed the role of intuition, along with imagination and feeling, citing them as important influences to that consciousness. With Todos los tiempos confluyen, Berger cites roberto Bolaño and speaks specifically about language, the technicalities of past and present tense and implicitly accepts the role of painter-as-translator. The friendship between lin-Yi and Berger grew out of the mutual admiration for each other’s work in spite of the immense language barrier that still precludes them from easily communicating. While working in a Chinese language school in 2010, lin-Yi came across a whole stash of unused rice paper and, being an artist, the administration told him to keep it and use it for his art. He, in turn, just gave it to Berger, who decided to use it and joked that if she could paint 300 of them, she’d learn Chinese. This appreciation for the material qualities of the Mao Bianzhi paper can only come with the distance of someone who doesn’t belong to that culture. These are leftovers from an earlier time, when Chinese calligraphy was taught at school, when the teachers actually knew how to properly write in Chinese. The current Taiwanese generation of students that attend the school have grown up with Spanish as their primary language. despite the rigorous examinations that are part of the formal education at the school, these efforts are not enough to keep assimilation at bay. Attracted by the story behind the paper and its graphic quality, Berger saw an opportunity where lin-Yi only saw reminders of his own education in Taiwan. it is fitting that she tried to establish a relationship to his culture through a material, not only that he gave her, but that served an educational purpose as well. in a book about the Korean immigration in Argentina, the social anthropologist Carolina Mera writes that you are what you feel to be through contact with others. An individual’s identity is the result of this exchange.5 if Berger’s artistic practice was an object, it’d be a stamped passport, a visa to come and go as she pleases. Part repetitive task, part painting as social practice, Berger knows she can, at best, be a translator, but that doesn’t stop her from trying.

Bibliography:

1. luo X, Fanyi Lunji [Selected Papers on Translation], Beijing, Shangwu Yinshuguan, 1984, p. 558.

2. Chuanmao, Tian, Fu Lei’s Translation Activity and Legacy, Journal of language and Culture Vol. 2 (10), october 2011, pp. 174-183.

3. idem, p. 179.

4. La Ene, of which I’m also a co-founder, was created after a video conference with Mexican curator Cuauhtémoc Medina, in which he pointed out how ridiculous it was that Buenos Aires, though pretending to be a cultural hot spot, lacked a contemporary art museum. Through exhibitions, workshops and a residency program, la Ene aims, not only to point out the institutional void that exists in Argentina regarding contemporary art, but also contributes to a scene that lacks international projection and interaction with its latin American peers.

5. Carolina Mera, La inmigración coreana en Buenos Aires: multiculturalismo en el espacio urbano, Buenos Aires, Eudeba, 1998.

0 notes

Photo

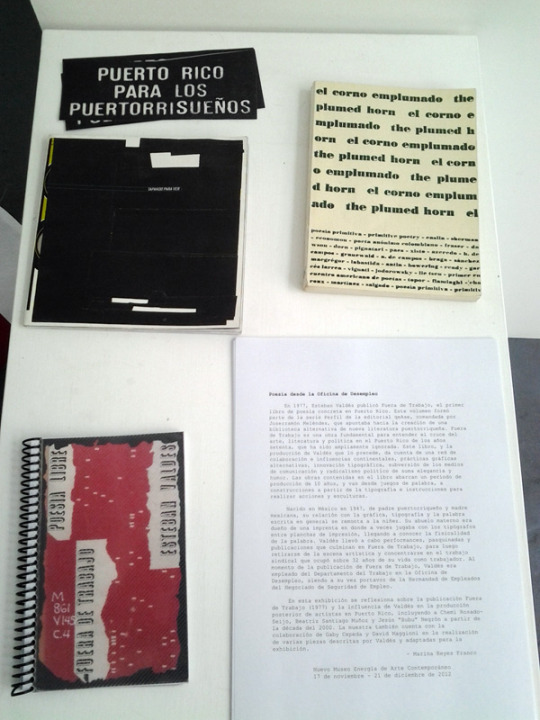

Poetry from the Unemployment Office

Esteban Valdés, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Chemi Rosado Seijo, Jesús "Bubu" Negrón, with David Maggioni and Gaby Cepeda

Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo - La Ene

Buenos Aires, Argentina

November 2012

In 1977, Esteban Valdés published Fuera de Trabajo, the first book of concrete poetry in Puerto Rico. This volume was part of the Perfil series of the publishing house Editorial qeAse, commanded by Joserramón Meléndes, which aimed at the creation of an alternative library of new Puerto Rican literature. Fuera de Trabajo is a fundamental work to understand the intersection of art, literature and politics in Puerto Rico in the seventies, which has been widely ignored. This book, and the production of Valdés that precedes it, accounts for a network of collaboration and continental influences, alternative graphic practices, typographic innovation, subversion of the media and political radicalism of great elegance and humor. The works contained in the book cover 10 years of poetic production, ranging from word games to constructions based on typography and instructions for actions and sculptures.

Born in Mexico in 1947, of Puerto Rican father and Mexican mother, his relationship with graphics, typography and the written word in general stems from his own childhood. His maternal grandfather owned a printing house where he sometimes played with typesetters between printing plates, and it’s there that he got to know the physicality of words. Valdés carried out performances and wrote poems that culminated in Fuera de Trabajo, before retiring from the artistic scene and concentrating on the union organizing work that occupied him for over 32 years of his life as a worker. At the time of the publication of Fuera de Trabajo, Valdés was an employee of the Department of Labor in the Unemployment Office, and was a spokesperson for the Brotherhood of Employees of the Bureau of Employment Security. In this exhibition we reflect on the publication Fuera de Trabajo and the influence of Valdés on the subsequent production of artists in Puerto Rico, including Chemi Rosado-Seijo, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz and Jesús "Bubu" Negrón, starting in. The show also includes collaborations with Gaby Cepeda, and David Maggioni who helped realize two pieces described by Valdés and adapted for the exhibition.

*Adaptations of this exhibition have also been presented in Phosphorus (São Paulo, Brazil) and Bosque Auxiliar (Naguabo, Puerto Rico)

Buenos Aires:

São Paulo:

Naguabo:

0 notes

Photo

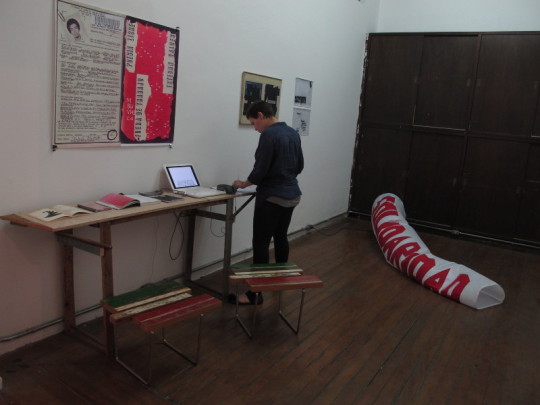

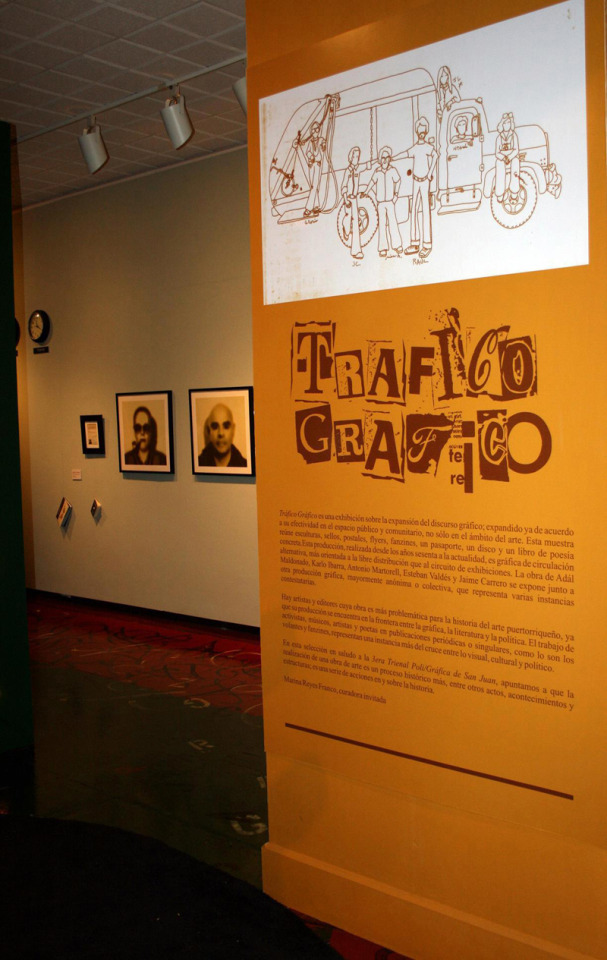

Graphic Traffic

Dr. Pío López Martínez Museum, University of Puerto Rico, Cayey

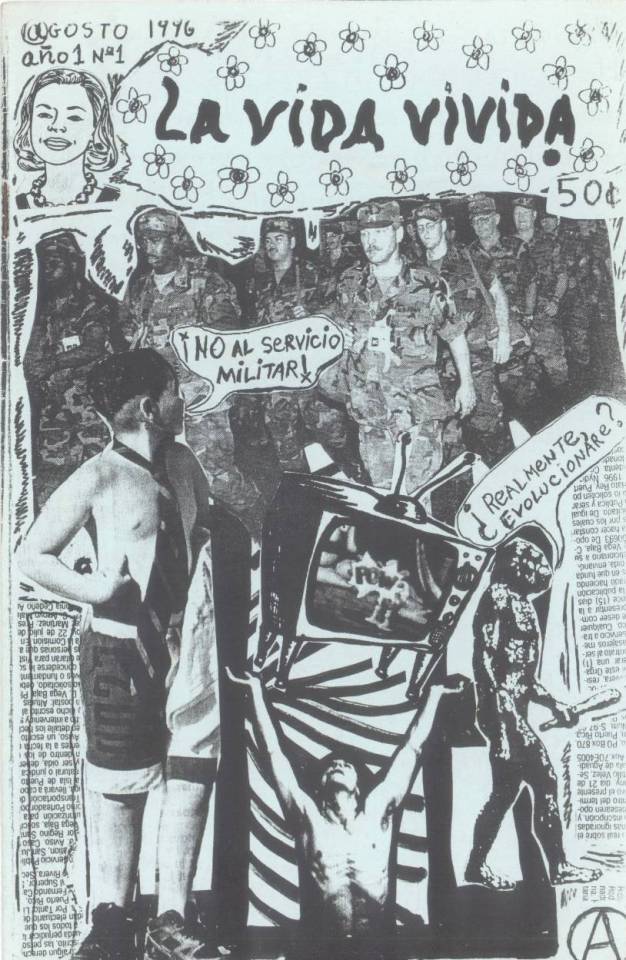

Graphic Traffic is an exhibition about the expansion of graphic discourse in its effectiveness in the public realm, beyond the field of art. This exhibition brings together sculptures, stamps, postcards, flyers, fanzines, a passport, a record and a book of concrete poetry. These works, created between the 1960s and the present, have circulated through alternative methods and spaces, often not within art exhibitions. The work of artists Adál Maldonado, Karlo Ibarra, Antonio Martorell, Esteban Valdés, and Jaime Carrero is exhibited along with other graphic production, mostly anonymous or collective, which represents several contestatory instances.

A letter from José Luis González accompanies Martorell's stamps; a deceptive text about the life and work of a newly arrived immigrant to New York whose beach will now only be that of the invaded roofs of the city: La Playa Negra / Tar Beach. Another set of pieces included in the exhibition, the Martorell Self-Retrospective Lamps, refer to the metaphor of circulation and transit. The lamp posts hold car mirrors with cut out xylographs from Martorell’s Communion series, along with fragments of portraits of political prisioners linked to the Boricua Popular Army. We see them and we see ourselves; we look for each other and we find them, always there waiting to get out of the mirror. Meanwhile, Karlo Ibarra’s Souvenir Stories are postcards created from a selection of images of events and protests that happened in Puerto Rico in 2009. They’re freely available to take and send, but they’re already addressed to places like the Capitolio and Fortaleza in Puerto Rico or the White House in Washington D.C..

There are artists whose work is more problematic for the history of Puerto Rican art, since its production is on the border between graphic art, literature and politics, with a closer relationship to cultural studies, than to visual art production or the idea of art as a precious artifact. The agency of activists, musicians, artists and poets in periodical or singular publications, such as flyers and fanzines, represent another instance of the intersection between the visual, cultural and political. Publications like Il Trassero or Boricuas Bestiales use xerography to make satirical comments about art and its cultural agents, or articles about politics and punk music, respectively. Il Trassero was created by Jaime Carrero and other colleagues at the Inter-American University of San Germán, for distribution among friends and the university community, as a satire where they cite places and artists of international recognition in relation to them in the town. Writing about bands like Actitud Subversiva, Naborias, Guatiao, Lopo Drido or Golpe Justo, among others, Boricuas Bestiales and other publications about punk and hardcore bands were identified with national feelings, linked to their development in the shadow of the 5th centenary of the Spanish invasion to Borikén.

Omar Dauhajre and Javier Tous, editors of Boricuas Bestiales, have also lent other magazines from their collection: 'zinevergüenza, edited by Taína Rosa, Eniznikufesin' Zine edited by Daniel Rivera, as well as Una Sola Escena and La Vida Vivida by Félix Santiago, all published in the nineties. Also in a similar attitude of identification with a remote indigenous past as an alternative or vindication of history, Adál Maldonado and the historian Iván Collazo have conceptualized Otoao, a new nation with its own passport and open inscriptions.

The activism and call for citizen participation is evident in several flyers by the Puerto Rican Socialist Party and the 1980 non-partisan election campaign El Gobierno Araña, led by a group of cultural agents organized against then governor Carlos Romero Barceló, whom they considered a murderer. The general elections of 1980 in Puerto Rico mark a very important moment in the history of the country because, among other things, they marked a milestone in citizen and artistic intervention in island politics through an independent campaign called El Gobierno Araña. This campaign, carried out by the Committee for the Defense of Puerto Rican Culture, consisted of a graphic design and a song distributed in multiple forms, whether printed, passing the music through loudspeakers attached to trucks or in radio ads. The Committee was made up of a group of artists, writers and publicists with different levels of participation and prominence, due to the need of some members to remain anonymous. For this organization, the political struggle was based and centered on a cultural struggle. The campaign was conceptualized by Edwin Reyes who also wrote the lyrics of the song, with anonymous graphic design (actually created by Gache Franco) and the musical collaboration of Andrés Jiménez and Grupo Cañiña (alias Grupo Mapeye).

In a similar attitude regarding the distortion of logos and political criticism, Harry Hernández has produced a series of satirical stickers that allude to our colonial reality. Likewise, Dinorah Marzán represents another instance of using non-traditional media to share her word. This poet devised an edition of water bottles as part of an editorial project entitled Oblivion 140. "I will quench your thirst for you by drinking your forgetfulness," is both an advertising product and a poetic object.

The work of Esteban Valdés, born in Mexico and raised in New York and Puerto Rico, is particularly important, since it represents the first book of concrete poetry published by a Puerto Rican. With characteristic hybridity, Valdés wanted to insert himself in the literature world of his time but was rejected by the establishment. His poems were in the conceptual plane; some were typographical or semantic games, while others consisted of instructions to build sculptures or perform actions. Decades later in the early 2000s, a group of artists belonging to the M & M Proyectos initiative led by Michy Marxuach, identified his poems as a previously unknown antecedent of their own work and understanding of art. One of them, Marxz Rosado, made the sculpture The process to get the signature of Pedro Albizu Campos in neon lights, which he later donated to the Institute of Culture, as indicated in the instructions. In this exhibition in salute to the 3rd Poly/Graphic Triennial of San Juan, we point out that the realization of a work of art is another historical process, among other acts, events and structures; a series of actions in and about history.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ladrón de Museos [Museum Thief]

Franco Ferrari

Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo - La Ene

Buenos Aires, Argentina

March 2012

In Museum Thief, Franco Ferrari presents work developed during his residency at La Ene. Ferrari works with high-resolution images hacked from museum websites, along with the idea of high art, ancient museums as palaces converted into public spaces that were meant to educate the people, and the novel idea that you can build your own museum. Ferrari plays with the notions of the greatness of that art of the past, appropriation through technology, DIY, and theft, among other ideas.

"In a Google search for Tiepolo's frescoes, I came across The Immaculate Conception. The file weighs almost 100 mb and, at 300 dpi, it could measure 2 meters. I was obsessed with the quality of the reproductions, it was no longer a matter of using photoshop to enlarge them and make them look good. It was a question of improving the search on the internet and getting the images that turned up. The shines, the craquelure, even the paintings with their original frames. I realized that I could open a museum anywhere. We would also have the Mona Lisa, and even bigger if we wanted. In the end I would be printing stolen reproductions of the internet, at an almost professional quality. My obsession for the faithful copy brought me here, because after all, if I could, I would be a forger of paintings."

0 notes

Link

Born Wild, a book about Gala Berger’s “Chino para principiantes” series edited by Marina Reyes Franco

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Zaqistani Embassy in Buenos Aires

A project by Zaq Landsberg, Sofía Gallisá Muriente and other Zaqistani citizens, in La Ene, Buenos Aires, Argentina - January, 24 - February 9, 2012

---

January 20, 2012

The Zaqistan State Department is pleased to announce the opening of the first Zaqistan Embassy in Buenos Aires, Argentina. There will be a formal opening ceremony on Tuesday, January 24 beginning at 7:30pm. Run in conjunction with Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo, the Embassy will be open for the next three weeks.

The Embassy of Zaqistan is an effort to expand Zaqistan’s global presence and influence beyond its desert borders. Buenos Aires, being an international city, a hub of South America, and also having a rich cultural history, especially in reactionary conceptual art, is a natural place to extend the reach of Zaqistan.

The Embassy features a History of Zaqistan exhibit, historicizing the recent past in display cases with artifacts and wildlife specimens, photographs, maps, wall texts, a timeline, and educational videos. There will also be a naturalization/passport station, where visitors may choose to become citizens, take the oath, apply and get issued a passport.

The Embassy will also function as a space for Zaqistani outreach through public programming. One such outreach program is a nationbuilding workshop for children, where local youth will found and develop their own nations. Other outreach projects in development include lectures on Zaqistani History and Zaqistan in historical context, desert survival demonstrations, and the designing, publishing, and translating of Zaqistani texts.

0 notes

Video

youtube

"No somos huérfanos: la recuperación del olvido"

Presentación en "Fe de erratas: Arte y Política"

Museo de la Memoria en Rosario, Argentina

11 de julio 2015

A través de anécdotas y videos, se plantean varias recuperaciones históricas de momentos en la historia y el arte en Puerto Rico que han estado relacionadas a la política y al activismo. Este breve recuento apunta hacia la ampliación de la concepción de prácticas artísticas de motivación política, tomando en consideración la relación entre varios actores culturales que actúan en el límite de la poesía, la gráfica y la acción política.

En el contexto del Museo de la Memoria, traigo a colación ciertos gestos y acciones gráficas o performáticas realizadas por artistas y poetas en Puerto Rico, particularmente en la década de los setenta, que han quedado mayormente fuera de la historia del arte local. Propongo hacer un recorrido breve e incompleto y luego trazar unos paralelismos con la actualidad y las formas en que se están utilizando los recursos del arte para hacer política ahora. Algunas de las historias que he recopilado tienen una historia oral particular y otras las cuento yo.

0 notes

Link

Tesis presentada para el título de Maestría en Historia del Arte Argentino y Latinoamericano, Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales de la Universidad Nacional de San Martín en Buenos Aires, Argentina

En la década del setenta se desarrollaron prácticas gráficas alternativas que actuaron en la frontera entre lo poético y lo político y han sido mayormente excluidos del discurso canónico de la historia el arte en Puerto Rico porque implican un desplazamiento gráfico respecto de la ortodoxia de la gráfica y su circulación en el país. En este trabajo se estudia y amplía la concepción de prácticas artísticas de motivación política entre 1970 y 1980, tomando en consideración la relación entre varios actores culturales que actuaron en el límite de la poesía, la gráfica y la acción política.

0 notes

Link

Texto sobre estudios poscoloniales y su relación con la producción artística contemporánea en Puerto Rico a través de la obra de los artistas Allora & Calzadilla, Charles Juhasz-Alvarado, Carolina Caycedo, Karlo Ibarra y Radamés "Juni" Figueroa.

0 notes

Photo

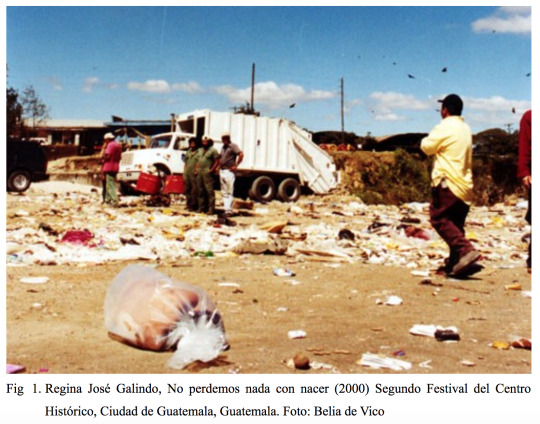

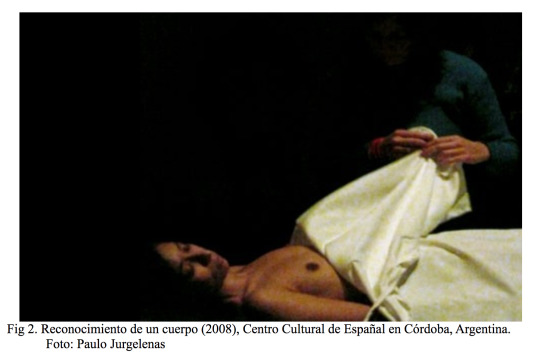

El cuerpo social por/en/de Regina José Galindo

Para la artista guatemaleca Regina José Galindo, su cuerpo no es individual. Ese cuerpo que ella, a través de sus acciones o performance, ha sometido a numerosos actos violentos y de automutilación, es un cuerpo colectivo, reflejo de las experiencias de otros.1 Si bien el gran tema de las indagaciones históricas y filosóficas de Michel Foucault fueron sus estudios sobre el poder, entonces las piezas de Galindo podrían llamarse ejercicios sobre los efectos del poder sobre su propio cuerpo. Foucault clarifica que, para él, su objetivo siempre fue el de crear una historia de las distintas maneras en que los seres humanos son hechos sujetos a través de unos mecanismos de poder.2 Esta creación del sujeto, para luego pasar a objetivarlo, es uno de los grandes temas de sus escritos y un punto en común con la obra de Regina José Galindo. Según Foucault, el cuerpo social “es la materialidad del poder sobre los cuerpos mismos de los individuos.”3 Este cuerpo social es encarnado por Galindo, quien subvierte los métodos de objetivación del sujeto al ser una artista que se subjetiva y a su vez se objetiva con fines artísticos en sus performance. Los métodos utilizados por Galindo para lograr esto son la encarcelación, la tortura, la automutilación y el sometimiento a métodos disciplinarios. A través de este análisis, se pretende tratar ciertos temas entre los que se encuentran los dispositivos de disciplinamiento y regulación de los cuerpos, el cuerpo y la vida como objetos/sujetos del poder, y el poder de la vida como resistencia a través del body art o performance.

Se le llama performance a un tipo de arte en el que uno o más individuos propician un evento o ejecutan una serie de acciones que involucran el cuerpo del artista, y a veces al público, en un espacio y tiempo determinados. En la mayoría de los casos, los eventos están claramente separados del resto de la vida, y las acciones sirven para ser interpretadas, reflexionar y estar comprometido emocional, mental y físicamente en un proceso de autoreflexión y experimentación.4 El proceso y resultado del evento es denominado arte. Aunque tiene características del teatro, el arte de performance, como se entiende en nuestros días, deviene del arte conceptual y vanguardista de los años 60, junto a los happenings y el body art. El performance también tiene precedentes modernos en vanguardistas japoneses, futuristas rusos y las declamaciones de poesía Dada en el Cabaret Voltaire. El énfasis del performance es en el cuerpo y usualmente son sencillos en cuanto a los objetos, muebles, lugar donde se llevan a cabo y la ropa que se utiliza, muchas veces recurriendo al desnudo. Marvin Carlson, en su ensayo “What is Performance?” apunta que el performance siempre es para un público o audiencia que reconoce y valida las acciones como tal, aún cuando la audiencia sea uno mismo. Carlson diferencia el performance de otras artes performativas porque no están basados en trabajo o personajes creados por otros artistas, sino que se basan en sus propios cuerpos, biografías o experiencias propias dentro de una cultura o en el mundo, hechas performance por su conciencia de ellas y el proceso de mostrarlas a una audiencia.5 Según Carlson, el arte del performance trae a colación preguntas sobre lo que significa ser postmoderno, la búsqueda de una subjetividad e identidad contemporánea, la relación del arte a las estructuras de poder, y los varios retos planteados por el género y las etnias. Jon McEnzie, en su libro Perform or else: from discipline to performance, entiende el performance dentro de lo que se ha denominado performance studies y, específicamente, el performance cultural, que incluye una gama de disciplinas que van desde los rituales religiosos hasta el arte del performance, pasando por el teatro, y danza, y hasta los actos de colación de grado. A través de este entendimiento, podemos comprender su declaración de que el performance cultural es para el siglo 20 y 21 lo que la disciplina fue para los siglos 18 y 19. Según McEnzie, “el performance cultural interviene en las normas sociales como un ensamblaje de actividades con el potencial de sostener los arreglos sociales o cambiar a las personas y las sociedades.”6 Aunque en muchas vertientes del performance cultural, estas acciones sirven para reafirmar las estructuras existentes, como puede ser el caso de un bar mitzvah, en este caso nos concentraremos en el potencial transgresivo o de resistencia que tiene el arte del performance al incitar, asertar, acusar y oponer.

En otro ensayo de McEnzie,titulado “The liminal-norm”, éste recalca la naturaleza liminoide del performance, paralelo a cruces de fronteras y transgresiones de límites, o grupos marginados. El performance y su eficacia se juzgan de acuerdo a términos de liminalidad: “un modo de actividad cuyo 'entre-medio' espacial, temporal y simbólico permite que las normas sociales sean suspendidas, retadas, invitadas a jugar o incluso transformadas.”7 Este entremedio es análogo al concepto de heterotopía auspiciado por Michel Foucault. Una heterotopía es un espacio fuera del espacio social e institucional diario, como puede ser un tren; espacios físicos que son cargados de símbolos, donde las relaciones sociales y políticas pueden ser reconfiguradas. Pensemos, como lo hace Coco Fusco en su libro Corpus Delecti: performance art of the Americas, que el arte del performance crea esos espacios.8

La obra de Regina José Galindo, como la de todos los artistas, debe ser analizada en dos niveles: por un lado, se analiza la pieza en sí y, por otro, se posiciona esa pieza dentro del cuerpo de obra de la artista. De esta manera entendemos cómo Galindo se ha constituido a sí como artista y cómo sujeto y objeto de su arte y son éstos, precisamente, algunos de los conceptos presentados por Foucault a través de varios escritos, como Locura y Civilización, El Nacimiento de la Clínica y Vigilar y Castigar. Foucault habló de las prácticas divisorias y la objetivación como una de tres de estas prácticas (junto a la clasificación científica y la subjetivación). Las prácticas divisorias son modos de manipulación que combinan la mediación de la ciencia y la práctica de la exclusión – usualmente en un sentido espacial, pero siempre socialmente.9 Según Foucault, “el sujeto es objetivado por un proceso de división, ya sea dentro de él mismo, o de los otros. En este proceso de objetivación, se les da una identidad social y personal a los seres humanos.”10 La objetivación de los individuos parte de una masa indiferenciada y luego de otras poblaciones seleccionadas, ya sea la clase trabajadora, y aquellos grupos definidos como marginales. En este modo de objetivación, el sujeto puedo ser visto como víctima, “atrapado entre los procesos de objetivación y encierro”.11 En sus análisis, Foucault se refería al aislamiento de los leprosos, encarcelamiento de los pobres, locos y vagabundos. En el caso de la obra de Galindo, ella se objetiva a sí misma, asumiendo sobre su cuerpo esas diversas identidades que les han sido dadas, a través de procedimientos de poder y saber a grupos dominados o formados a partir de las prácticas divisorias.

Con ocasión del Segundo Festival del Centro Histórico en Ciudad Guatemala en el año 2000, Galindo se colocó dentro de una bolsa de plástico transparente, “como despojo humano”12 y fue depositada en el basurero municipal de Guatemala. El performance se llamó “No perdemos nada con nacer” (Fig 1). Esta acción, tan violenta y tan pasiva a la vez, tiene el radical efecto de convertir a Galindo, no solamente en una artista que encarna el dolor físico de otros, sino en literalmente una cosa a ser desechada. La imagen de un cuerpo humano en un vertedero nos recuerda a cadáveres depositados allí para pasar desapercibidos, ya sean de adultos o de niños, o incluso fetos. También recalca la realidad de los trabajadores municipales, definitivamente uno de los trabajos más bajos de la sociedad. Esta acción/inacción y sometimiento pasivo a métodos de disciplina en sus performances ha sido repetida en numerosas ocasiones. En un performance titulado “Valium 10ml”, también realizado en el año 2000, Galindo se inyectó 10 miligramos de Valium y permaneció sedada, cual paciente mental, en el Museo Ixchel en Guatemala.

Años más tarde, en el Centro Cultural de España en Córdoba, realizó “Reconocimiento de un cuerpo” (fig 2), donde permaneció completamente anestesiada sobre una camilla, su cuerpo cubierto con una sábana que los visitantes podía levantar para “reconocer” el cuerpo de Galindo, o de una mujer asesinada, o una víctima de represión, o cualquiera que pudiera ser la interpretación del observador luego de ver el cuerpo inerte y desnudo de una mujer joven de rasgos indígenas. La artista, quien usualmente realiza piezas relacionadas a la historia de Guatemala, también idea otras piezas que hacen alusión a los países que visita. En el caso de “Reconocimiento de un cuerpo”, el centenar de visitantes al centro cultural durante el performance no pueden si no haber pensado en la historia argentina y sus propios desaparecidos. Para Galindo, sin embargo, es también un simple reconocimiento de cadáver: cualquier cuerpo, cualquier muerto, uno de los tantos asesinatos de mujeres en Guatemala que ha denunciado a través de su obra. La pieza “(279) Golpes”, realizada durante la 51 Bienal de Venecia y que fue de las obras que le valieron un León de Oro a la mejor artista joven de la Bienal, es otro ejemplo de esta tendencia en el corpus de obra de Galindo. Durante este performance, más bien sonoro, ella permaneció encerrada en un cubículo fuera de la vista de todos, dándose un golpe por cada mujer asesinada en Guatemala entre el 1ero de enero al 9 de junio del 2005. El sonido de los golpes, amplificado, se proyectaba en la sala, sin que la mujer que sufre sea vista en ningún momento.

Como ya hemos visto, las disciplinas, entendidas como una manera de ejercer el poder en que se regula el comportamiento de los individuos del cuerpo social a través de la regulación de la organización del espacio, tiempo y comportamiento humano, son un recurso utilizado en innumerables ocasiones en la obra de Galindo. El aislamiento o encierro, ya sea en prisión, hospital o esa combinación de ambos llamada manicomio, es otro de los dispositivos objetivadores recurrentes en su obra. Galindo juega constantemente con lo literal y metafórico en su trabajo. En la instalación/performance “America's Family Prison” (San Antonio, Texas, 2008) (figs 4 y 5), Galindo se sometió, junto a su esposo e hija, al encierro en una cárcel modelo en una sala de exhibición en Artpace en Texas. Para Foucault las cárceles son fascinantes porque “el poder ni se oculta ni es enmascarado, muestra su feroz tiranía en los más mínimos detalles.”13 En los Estados Unidos, especialmente en el estado de Texas, esta aseveración no puede ser más contundente, debido a su alta taza de prisioneros, inmigración ilegal, abundancia de paramilitares caza inmigrantes, y la larga cola esperando la pena de muerte. La celda fue alquilada por $8,000, pero ésta usualmente es utilizada para mostrarla en ferias de la industria de cárceles privada de los Estados Unidos, uno de los negocios que ha prosperado desde la década de los ochenta. Con su performance, Galindo muestra la dura realidad de familias, muchas de ellas compuestas de inmigrantes a la espera de una decisión sobre su posible estadía en los Estados Unidos.14 Las cárceles estadounidenses, siempre duramente criticadas por la manera discriminatoria en que han sido pobladas de minorías en dicho país, ahora también albergan familias enteras. En “Proxémica” (Colectiva Días Mejores, Centro Cultural de España. San José, Costa Rica, 2003), la artista utilizó bloques y cemento para hacerse su propia cárcel, para luego hacer un hoyo para salir con un martillo y cincel. En “Toque de queda” (París, 2005), Galindo permaneció aislada dentro de una sala de exhibición francesa por diez días, durante los cuales escribió y dibujó en las paredes sus reflexiones del encierro, ilustrando como, a través de una práctica divisoria puede ser dada una identidad, lo que Foucault llama la objetivación como “proceso de división dentro de sí mismo o de los otros.”15 Sin embargo, hay piezas de Galindo que son mucho más drásticas en el encarcelamiento, ya que la llevan prácticamente la inmovilidad total a través del uso de varios dispositivos. En “Cepo” (Spazio Volume, Roma, Italia, 2007) (fig 8), ella permanece 12 horas detenida por un cepo en el que, mientras Galindo esá sentada en el piso, le condena manos y pies en la estructura de madera y metal. En “Yesoterapia” (República Dominicana, 2006) estuvo enyesada de cuerpo entero por cinco días. En “Camisa de Fuerza” (Bélgica, 2006) permaneció tres días consecutivos en una camisa de fuerza en el Psiquiátrico de Sint Alexius. En este caso, la artista recalca la estigmatización e inmobilización (literal y metafórica) de todo aquel que no se ajuste a las rígidas estructuras sociales. Para Foucault, “...si no eres como todos los demás, entonces eres anormal, y si eres anormal, entonces estás enfermo. Estas tres categorías, no ser como todos los demás, no ser normal y estar enfermo no son lo mismo pero han sido reducidas a la misma cosa.”16 Esta pieza no sólo recalca la manera en que vemos la psiquiatría, sino como vemos a todos los que son distintos: se encierran, la paralizan y se posicionan fuera de la sociedad.

Si bien estos otros performance han sido más generales en contexto o realizados fuera de su país,“Mientras, ellos siguen libres” es muy específico en la denuncia que realiza. En el performance, llevado a cabo en el Edificio de Correos de Guatemala en el año 2007, es una denuncia y reclamo por las violaciones a mujeres indígenas durante el conflicto armado en Guatemala. “Mientras, ellos siguen libres” es uno de los performance que Galindo realizó durante su embarazo, la mayoría de los cuales realizaba atada o de alguna manera confinada a un espacio (“Carnada” (fig 12), “Isla”). En esa ocasión, y con ocho meses de embarazo, Galindo permaneció “atada a una cama-catre, con cordones umbilicales reales, de la misma forma que las mujeres indígenas, embarazadas, eran amarradas para ser posteriormente violadas.”17 Esto fue como parte de una “cruenta estrategia militar para que las mujeres abortaran y dificultar así la supervivencia de los pueblos indígenas.”18 Esta no es más que una de las numerosas instancias en que Regina José Galindo ha encarnado el papel de la víctima, aunque siempre en resistencia, de las atrocidades en su país.

El performance por el cual Galindo obtuvo más fama fue “¿Quién puede borrar las huellas?” (fig 13 y 14), otra instancia de denuncia del poder del Estado sobre la vida, aunque sea en retrospectiva. En el 2003, la Corte Constitucional Guatemalteca aprobó la candidatura presidencial del ex dictador Efraín Ríos Montt. En respuesta a la decisión de la corte, la artista caminó desde la Corte Constitucional al Palacio Presidencial cargando un recipiente lleno de sangre humana, en la cual metía sus pies para luego ir marcando su camino, y el de todos los muertos que Ríos Montt tiene a sus espaldas. Este recorrido, corto y silencioso, también va dirigido al ciudadano que olvida su historia. Según Foucault, el humano es un animal cuya política pone su existencia como ser vivo en cuestión.19 En la Historia de la Sexualidad, Michel Foucault hace una genealogía del poder soberano y su consecuente transformación del poder de quitar la vida y dejar vivir hacia uno de “foster life or disallow it to the point of death.”20 Ya el que gobierna no es un soberano en cuyo nombre hay que ir a la guerra, mas sin embargo, señala Foucault, desde el siglo XIX hasta nuestros días, han habido un sin número de genocidios y han ocurrido las guerras más feroces. Según Foucault, “never before did regimes visit such holocausts on their own populations”21 y añade que es como “administradores de vida y sobrevivencia, de cuerpos y de razas, que tanto regímenes han sido capaces de tantas guerras, causando la muerte de tantos hombres”22 Para Foucault, “si el genocidio es el sueño de los poderes modernos, no se debe a un retorno reciente al antiguo derecho de matar; es porque el poder está situado y ejercido al nivel de la vida, la especie, la raza...”23 Es aquí donde la naturaleza mestiza de Galindo toma significado en cada uno de sus performance, especialmente aquellos realizados embarazada, pues el sexo es asumido como un issue político.

El bio-poder sobre el cuerpo humano tiene una dimensión no sólo biológica, sino que el cuerpo es visto como un objeto a ser manipulado. Tal es el caso en el performance “Himenoplastía” en que la artista se somete a una reconstrucción quirúrgica de su himen y, por ende, su “virginidad”. Esta operación fue realizada por 3,700 quetzales, la moneda guatemalteca. A diferencia de las mujeres que se realizan esta operación en países del Primer Mundo, en partes de Latinoamérica y Africa se hace como modo de sobrevivir y ser aceptado en sociedad. Este performance y operación de dudosa legalidad fue propiciado por la artista haber visto un aviso en el periódico que anunciaba “le devolvemos su virginidad”.24 Este doble estándar hacia la mujer también es el tema del performance “Perra” (2005) en el que Galindo corta su muslo hasta escribir “perra” en su piel., en referencia a una de las múltiples palabras que se han encontrado en cuerpos de mujeres violadas y asesinadas en Guatemala. Aún sin físicamente agredirlas, este tipo de insultos se dirigen comúnmente a las mujeres, pero en “Perra” Galindo lo asume y se estigmatiza ella misma para, precisamente, de- estigmatizar porque señalar la herida, ya sea literal, como en este performance, o metafórica, es una de las estrategias de Galindo. En el caso de la operación, éste es uno de los nuevos procedimientos, o uniones de saber y poder que Foucault llama tecnologías, que se unen para la objetivación del cuerpo.25

En Verdad y Formas Jurídicas de Foucault, él señala que hay un poder epistemológico, un poder para extraer conocimiento de individuos y extraer conocimiento sobre esos individuos – quienes a su vez se encuentran bajo observación, y el conocimiento que se extrae de ellos se deriva de su propio comportamiento.26 Pero, ¿qué sucede cuando éstas no son las condiciones? Entonces ocurre la tortura. Esta manera de coaccionar confesiones de las personas ocurre cada vez más en nuestros días de estado de excepción. En este mundo post 9/11, el terrorismo le quita la capacidad al ciudadano de confiar en el Estado para que proteja su seguridad y el gobierno tiene una excusa para ser aún más restrictivo y represor, legal o incluso ilegalmente, buscando siempre un loophole. En su performance “Confesión” (Palma de Mallorca, 2007) (fig 17) Galindo señala precisamente esto a través de la recreación de una sesión de tortura con la técnica de waterboarding, en la que se simula el ahogamiento. Palma de Mallorca ha sido utilizado por el gobierno de Estados Unidos como punto de tránsito para prisioneros secretos que luego irán a uno de los países donde se han establecido prisiones secretas o no tan secretas en el caso de Guantánamo en Cuba. En “Confesión”, Galindo instruyó a un bouncer local para que, a pesar de sus protestas y resistencia, la sumergiera en un barril de agua que, no casualmente, antes contuvo petróleo. La acción ocurrió en un sótano en el que sólo estaban presentes el torturador, la torturada, un videógrafo y, fungiendo de fotógrafo, el teórico del arte inglés Julian Stallabrass. El público podía observar lo que ocurría a través de una pequeña rendija en la pared, o bien en una pantalla de televisión posicionada en la calle. A propósito de el cuerpo del condenado, Foucault señala en Vigilar y Castigar que ha habido un cambio hacia la desaparición de la tortura como espectáculo público pero en la era de las cámaras digitales, email y Abu Ghraib, ya la tortura no es privada.27 Tal vez se realice en privado, pero ahora es grupal, provoca risa a los torturadores y la presencia de una cámara añade a la humillación. Como bien señala Stallabrass, la lucha entre Galindo y su torturador puede ser leída como una alegoría de la absurda lucha entre naciones, no solamente en la guerra en Irak, sino también en lo que respecta al “comercio, privatización, 'cambios de regímenes' y el peso de la ley sobre naciones débiles por parte de las fuertes, apoyadas de la amenaza de pobreza y devastación en contra de aquellos que dicen no”.28 En “Limpieza Social” (Il Potere delle Donne. Galleria Civica Arte Contemporanea di Trento. Trento, Italia. 2006) (fig 18) Galindo recibe un baño a presión con una manguera, método utilizado para calmar manifestaciones o también para bañar a los recién ingresados a prisión. Thomas Micchelli, en una reseña de la exhibición de Galindo en Exit Art en Nueva York, señala que él recuerda vívidamente como se utilizaban las mangueras de agua a presión en contra de los deambulantes dormidos en las calles de Londres, quienes, mojados y con frío, debían buscar otro lugar donde pasar la noche con la posibilidad de enfermarse e incluso morir.29 Estas dos piezas son quizás las más visualmente violentas de la artista guatemalteca y ambas, por casualidad, son realizadas con el agua, una especie de bautizo violento.

El objetivo de las tecnologías, cualquiera que sea su forma institucional, es la de formar un cuerpo dócil que pueda ser usado, mejorado y transformado30 a través del entrenamiento del cuerpo, la estandarización de acciones a través del tiempo, y con el control del espacio designado. Análogo al pensamiento de Foucault, también hay un tiempo y espacio designado para el performance, un control del cuerpo, una voluntad de renunciar un poco a él y someterlo a cambios, mutilaciones y operaciones que lo objetivan pero que son asumidas por la artista, un sujeto tal como lo define Foucault, capaz de escoger como actuar. Según Galindo, “lo primero que yo hice fue escribir y de ahí vino el uso del cuerpo, ser yo misma objeto y sujeto de mis ideas. Utilizo el cuerpo para que éste sea reflejo de otros cuerpos.”31 Con este tipo de trabajo artístico, señala Stallabrass, Galindo se posiciona dentro de una tradición del arte contemporáneo en que el trauma político es capturado a través de trabajo que marca el cuerpo y lo hace doler.32

Para Foucault, el poder no es un ensamblaje de mecanismos de negación, rechazo, exclusión, sino que produce efectivamente y es probable que produzca a los mismos individuos.33 Foucault sugiere que hay varias maneras de combatir el poder y que, donde exista una relación de poder, siempre habrá la posibilidad de resistencia, no importa cuan opresivo sea el sistema. Para Galindo, el arte no cambia al mundo ni resuelve los problemas que causan la injusticia.34 También, como el arte de cualquier artista, estas acciones son casi siempre llevadas a acabo dentro de un circuito del arte, ante un público reducido e incluso elitista, pero esto no le quita valor y honestidad al trabajo de Galindo.

Según Michel Foucault,

“en la misma línea de sus conquistas, emerge inevitablemente la reivindicación del cuerpo contra el poder, la salud contra la economía, el placer contra las normas morales de la sexualidad, del matrimonio, del pudor. Y de golpe, aquello que hacía al poder fuerte se convierte en aquello por lo que es atacado...El poder se ha introducido en el cuerpo, se encuentra expuesto en el cuerpo mismo...”35

Foucault piensa que estamos en una lucha política constante y que la finalidad debe ser alterar las relaciones de poder en nuestra sociedad. En el arte de Regina José Galindo, un cuerpo no es sólo eso, sino el de muchos que trabaja y resisten a pesar de los sistemas que hieren, previenen, y exterminan. Los cuerpos sobreviven, resisten y crean.

Bibliografía:

1 Regina José Galindo, Artist's statement http://artwelove.com/artist/-id/f1f94bf1

2 Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Hubert Dreyfus y Paul Rabinow (eds.) Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982. p. 208

3 Michel Foucault, “Poder-Cuerpo”, en Julia Varela y Fernando Alvarez-Uría, eds. y trad., Microfísica del Poder, Madrid: Las Ediciones de la Piqueta, 1979. p. 104 – del original “Pouvoir-corps”. Rev. Quel Corps, n.° 2, septiembre 1975. págs. 2-5

4 Jon McKenzie, “The liminal-norm”, de The performance studies reader; Henry Bial, ed. (Routledge; Londres, 2004) p. 27

5 Marvin Carlson “What is Performance?”, de The performance studies reader; Henry Bial, ed. (Londres: Routledge, 2004) p. 71

6 Jon McKenzie, “The efficacy of cultural performance”, Perform or else: from discipline to performance (Routledge, Londres, 2001) p. 43 traducción de la autora

7 Jon McKenzie, “The liminal-norm”, de The performance studies reader; Henry Bial, ed. (Routledge; Londres, 2004) p. 27

8 Coco Fusco, “Introduction: Latin American performance and the reconquista of civil space” en Corpus delecti: performance art of the Americas. Nueva York:

9 Paul Rabinow, “Introduction”, The Foucault Reader, Nueva York: Pantheon Books, 1984. p. 8

10 Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, Hubert Dreyfus y Paul Rabinow, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982, p. 208

11 Paul Rabinow, “Introduction”, The Foucault Reader (Nueva York: Pantheon Books, 1984), p. 10

12 Regina José Galindo, “No perdemos nada con nacer” www.reginajosegalindo.com/es/trbj/0002.htm

13 Michel Foucault, Un Diálogo Sobre el Poder y otras Conversaciones (Madrid, Alianza, 2001)

14 “Las prisiones privadas para inmigrantes”, Border Action, http://www.borderaction.org/campaign3.php? language=sp&articleID=20 Accesado 2 de marzo, 2010

15 Michel Foucault, “The Subject and Power,” Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and

Hermeneutics, de Hubert Dreyfus y Paul Rabinow (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), p. 208

16 Michel Foucault, 'Je suis un artificier', en Roger-Pol Droit (ed.) Michel Foucault, entretiens. (París: Odile Jacob, 2004) p. 95

17 Regina José Galindo, “Mientras, ellos siguen libres” http://www.reginajosegalindo.com/es/trbj/0002.htm 18 Marc montijano Cañellas, “Regina José Galindo: El discurso del cuerpo”, de

http://www.homines.com/arte_xx_regina_jose_galindo/index.html Accesado el 30 de enero, 2010 19 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. I (1976; Nueva York: Pantheon, 1978), p. 143

Traducción de la autora

20 Michel Foucault, “Right of Death and Power over Life”, de History of Sexuality, Vol I, fragmento en The Foucault

Reader, Paul Rabinow (ed.), (Nueva York: Pantheon Books, 1984), p. 261 Traducción de la autora

21 Michel Foucault, “Right of Death and Power over Life”, de History of Sexuality, Vol I, fragmento en The Foucault

Reader, Paul Rabinow (ed.), (Nueva York: Pantheon Books, 1984), p. 259

22 Idem p. 260

23 Idem p. 260

24 Regina José Galindo, entrevista de Jacinta Escudos en http://www.filmica.com/jacintaescudos/archivos/ 006099.html Accesado 5 de febrero 2009

25 Paul Rabinow, “Introduction”, Paul Rabinow (ed.) The Foucault Reader (Nueva York: Pantheon Books, 1984) p. 17 Traducción de la autora

26 Michel Foucault, “Truth and Juridical Forms”, en J. Faubion (ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley, et al. Power: The Essential

Works of Michel Foucault 1954 – 1984. Volumen Tres. (Nueva York: New York Press, 2000) p. 83-4. Traducción de la autora.

27 Michel Foucault, “The Body of the Condemned”, Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Nueva York: Vintage Books, 1995) p. 8

28 Julian Stallabrass, “Performing Torture”, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/2009-additions/ Regina%Jos%C3%A9%20Galindo.doc p. 1

29 Thomas Michell, “Regina José Galindo”, http://www.brooklynrail.org/2009/11/artseen/regina-jose-galindo Accesado 8 de febrero, 2010

30 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (1975; New York: Vintage Books, 1979), p. 198

31 Regina José Galindo, entrevista de Jacinta Escudos en http://www.filmica.com/jacintaescudos/archivos/ 006099.html Accesado 5 de febrero 2009

32 Julian Stallabrass, “Performing Torture”, http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/2009-additions/Regina%Jos%C3%A9%20Galindo.doc Accesado 8 de febrero, 2010