Join me while I research different animal groups and post my findings to this blog!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Maybe if you looked at the diversity of loricariids then you'd feel better

(From Lujan et al. (2012). Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 12(124), 1-12)

490 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bandicoot. 🍓

#reblog#potoroo#bandicoot#marsupial#adorable#my highly professional animal identification skills. this guy is an adorable

83K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Blob-Headed’ Catfish among New Species Discovered in Peru

https://www.sci.news/biology/blob-headed-catfish-13540.html

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

This makes sense in hindsight given their geographic ranges, but I never consitered until now that nautiluses were named after the paper nautilus and not the other way around

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

My favourites are the flowers of Australian pea plants like parrot peas, dainty peas, and desert peas!

(Think of your favorite flower BEFORE reading options, if it's not mentioned or you don't have one please don't just pick your favorite from the options.)

What is your favorite flower?

-rose -tulip -lily -sunflower -iris -carnation -daisy -hydrangea -hibiscus -poppy -orchid -not listed/multiple/no favorite

983 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a monumental discovery for paleontology and the first of its kind "Mummy of a juvenile sabre-toothed cat Homotherium latidens from the Upper Pleistocene of Siberia"

Abstract The frozen mummy of the large felid cub was found in the Upper Pleistocene permafrost on the Badyarikha River (Indigirka River basin) in the northeast of Yakutia, Russia. The study of the specimen appearance showed its significant differences from a modern lion cub of similar age (three weeks) in the unusual shape of the muzzle with a large mouth opening and small ears, the very massive neck region, the elongated forelimbs, and the dark coat color. Tomographic analysis of the mummy skull revealed the features characteristic of Machairodontinae and of the genus Homotherium. For the first time in the history of paleontology, the appearance of an extinct mammal that has no analogues in the modern fauna has been studied. For more read here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-79546-1

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

First in Flight

The Pterygote Insects

(John & Kendra Abbot)

We've covered birds fairly in-depth on this blog, but what about the exclusive evolutionary category that birds are a part of: flying animals. True powered flight has only evolved 4* times among animals. The first, most diverse, and arguably most successful lineage of animals to evolve flight are the insects. This entry will focus on the origins and evolution of the flying insects (Pterygota), and subsequent entries will detail each order of insects to illustrate their immense diversity and success.

(* I have seen it proposed that flight may have evolved multiple times within Paravian dinosaurs including birds, particularly among microraptorines and scansoriopterygids, but evidence for truly powered flight in these lineages remains controversial and inconclusive, and given the close relationships between those two lineages and birds it is possible that flight may have been ancestral to the lineage leading to all three.)

(Kjer et al. 2016)

Let's first take a quick walk through the tree of Life to find where insects fit. Insects are animals (Metazoa), which seems obvious but surprisingly there are a number of people out there who view bugs as separate from animals. Within animals, they are Bilaterians like us, as well as Nephrozoans, but our shared ancestry diverges from there. While we are on the Deuterostome branch, meaning the initial hole (blastopore) that forms in our developing embryo becomes the anus, insects are down the adjoining Protostome branch, whose blastopore becomes their mouth instead. Within Protostomes, insects are Ecdysozoans (molting to grow), Arthropods (possessing an exoskeleton with segmented bodies and jointed limbs), Mandibulates (possessing a modified pair of appendages on the head for food processing), Pancrustaceans (turns out you can't have a monophyletic Crustacea without including insects!), and Hexapods (possessing 3 pairs of legs and a 3 segmented body). Once you get to the hexapods, you start to see some very insectoid organisms, like springtails and proturans.

(Left: springtail, Michel Vuijlsteke. Right: proturan, David R. Maddison)

These two groups form a sister group to the clade containing insects and their closest non-insect relatives: the diplurans.

(Steve Nanz)

We've finally arrived at the insects, but we're not quite at flight yet. There are 2 basal groups that branch of before the emergence of wings: the Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and the Zygentoma (silverfish). Sister to the silverfish is our group of interest, Pterygota, the winged insects.

(Left: bristletail, NCSU. Right: silverfish, Christian Fischer)

Insects proper are thought to have evolved sometime in the Devonian period, 419-358 Ma. The most often-cited "earliest insect" fossil is Rhyniognatha from the Rhynie chert, a famous 400 Ma Devonian formation in Scotland. The exact classification of the fragmentary specimen remains contentious; some analyses find it to be a insect, while others recover it as a myriapod.

(University of Aberdeen)

The oldest Pterygotes, and the oldest uncontroversial insect fossils, are Palaeodictyipterans like Delitzschala, which first show up from the mid-Carboniferous (330-315 Ma). These early Palaeodictyopterans were already highly derived and capable fliers with well-developed (and even pigmented) wings, meaning although these are the oldest fossil evidence of flying insects, the true origin must be a fair bit older for such structures to have been present by then. Therefore, insect flight and wings had likely evolved by at least the early Carboniferous, 350 Ma, if not older.

(Holotype of Delitzschala bitterfeldensis, Bracukmann & Schneider 1996)

(Life restoration of Delitzschala, Franz Anthony)

So we have an estimate for when flight evolved, and we have fossils of who was flying early on, but how did insects come evolve wings in the first place? Let's first start with the morphological aspect: what part of the insect body did wings originate from? In the other 3 groups of flying animals we know of (pterosaurs, birds, and bats), the wings are very clearly highly-modified forms of the ancestral forelimbs. Insect wings are not so easy to deduce. Their wings are not simply an arm or leg. You will often see 3 "main" hypotheses: wings evolved from the abdominal gills of aquatic larvae (epicoxial hypothesis), from outgrowths of the dorsal segments of the thorax (tergal hypothesis), or from side-appendages of the ancestral arthropod limb (pleural hypothesis).

(Depiction of the tergal and pleural structures hypothesized to have formed the insect wing, Clark-Hatchel and Tomoyasu 2016)

Recent studies on the ancestral state of Polyneoptera and Pterygota as well as studies on larval Palaeodictyipterans suggest that the ancestor of winged insects was terrestrial rather than aquatic, which points away from the abdominal gill hypothesis, as the ancestral insect would not have had aquatic larvae. That leaves the dorsal outgrowths and the side-appendages. Conveniently, a synthesis known as the dual-origin hypothesis has recently been proposed, combining the two hypotheses. Evidence from Palaeodictyipteran larvae, developmental studies on living insects, and genetics point towards a synthetic theory: wings began as outgrowths of the dorsal segments, and co-opted leg-related genes in order to become mobile appendages.

(Paleodictyopteran nymph wing pads showing dual-origin structure, Prokop et al. 2017)

As with all flying animals, the function driving selective pressure of the incipient wing-structures before they were capable of true flight has been much debated. The three main hypotheses are that proto-winglets were used to control descent when jumping or falling, to propel and steer during an aquatic nymphal stage, or as sails for dispersal of adults upon hatching from aquatic larvae. Given the findings of the ancestral pterygote having a terrestrial rather than aquatic lifestyle, the first hypothesis is currently favored. However insects may have first taken to the air, that fateful evolutionary leap changed the history of life on earth forever.

(Brisbane Insects)

Insects hit upon a major evolutionary innovation with the first development of powered flight, and they went on to become arguably the most diverse and successful group of animals ever. With species counts in the millions, there is much more to be explored as we dive into the many orders of winged insects.

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

My tour of sadness through Megacon.

81K notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1 - Phylum Porifera

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

The Phylum Porifera includes the sponges, also called sea sponges.

These animals are filter feeders that are bound to the sea bed in their adult forms, though some have free-swimming larva. Many species are important for building reefs. Their bodies consist of a mass of collagen jelly (called mesohyl) sandwiched between two main layers of cells. But they are not soft! Most sponges’ bodies are full of sharpened structural elements called spicules, which are made of either silica or calcium carbonate, so any predator biting into a sponge would get the same sensation as biting into shards of glass. Some sponges also have exoskeletons. Most sponges filter food particles via water flowing through their barrels and pores, but some sponges are carnivorous, using either sticky threads or barbed spicules to catch prey. Sponges may have been the first animals, and fossils of them date back to the Cambrian.

Propaganda under the cut:

Sponges could teach us how life began on earth.

As filter-feeding omnivores that feed on detritus, plankton, bacteria, and in some cases crustaceans and other small animals, sponges are an important part of the nutrient cycle in the ocean. Some are also symbiotic to other organisms, like algae, and provide homes for many reef animals.

Glass sponges, with skeletons of six-pointed siliceous spicules, are one of the longest lived animals on earth, with a possible maximum age of around 15,000 years!

While the spicules of most sponges render them too rough for human use, species in the genera Hippospongia and Spongia have soft, fibrous skeletons. Early Europeans used these dried out skeletons for many purposes, including cleaning, padding helmets, filtering water, painting, and even as contraceptives. The sponge industry almost brought these species to extinction, so nowadays most kitchen sponges are made of synthetic or plant-based material.

As revealed in the stage musical, the beloved cartoon character Spongebob Squarepants is an Aplysina fistularis (common name: yellow tube sponge), seen in the first image of this post.

spunch

#animals tournament!!#go vote!!#I will not be a useful datapoint in these polls because I will simply vote that I love all animals every time sorry

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinosaurs are weird

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

On a quest to find Tumblr’s favorite animal!

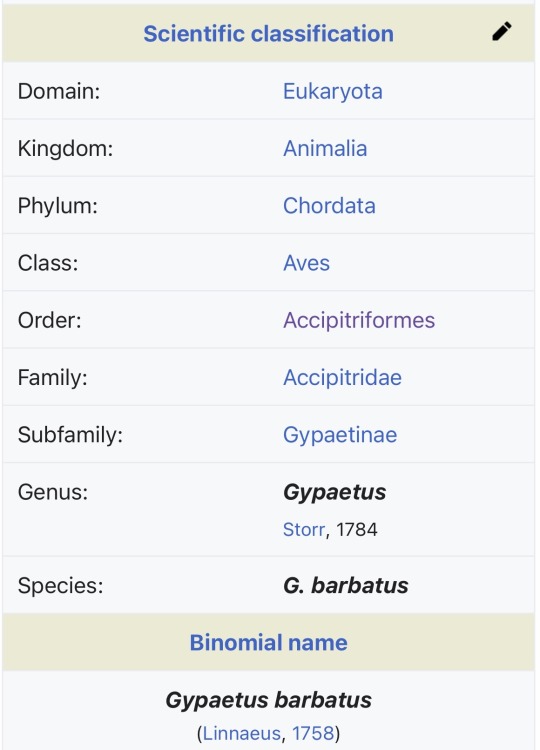

(Pictured is my personal favorite animal: the bearded vulture! Photo was taken by me… if you want to see more I post my photography on my instagram: SaritaWolf ;P)

Ever wondered how your favorite animal stacks up against other people’s favorites? Well you’ve come to the right place!

Here’s how this will work…

Polls will be ranked like so:

My fav is in this group!/This is one of my favorite animals!

I love these/this animal(s)

I like these/this animal(s)

I am neutral about these/this animal(s)

I dislike these/this animal(s)

I hate these/this animal(s)

If an animal is your favorite, it receives 5 points

If you love an animal, it receives 3 points

If you like an animal, it receives 1 point

If you are neutral about an animal, no points are added or subtracted to its ranking

If you dislike an animal, 1 point will be taken away

If you hate an animal, 3 points will be taken away

At the end of a polling period, that animal’s points will be its rank.

The top 20 or 50 or 100 or whatever (number to be decided on at a later date) will move on to the next round!

Polls will be open for 7 days

Since it’s not very feasible for me to make 1.5 million polls for every known species of animal, the first round of polls will be by Order.

If you want your favs to make it to the top, make sure you know what Order they’re in! This can be found via a quick Wikipedia search and a look-see right here (using the bearded vulture as an example):

The Bearded Vulture is an Accipitriform!

The top ranked orders will move on to the next round, where they will then be split into Families, and Round 2 will begin.

Round 3 will take the winning families and split them by Genus, then follow the same pattern.

Round 4 will take the winning genera and split them by Species, then follow the same pattern.

The ultimate round, Round 5, will pit the top 20/50/100 (number also to be decided at a later date) species against each other.

If no clear photos exist of a species, it will not be included in the polls. (So, if you’re a scientist who just discovered a new moth and it’s your favorite animal you better get those photos on iNaturalist quick)

You can have multiple favorites, I am not keeping track of that, but I do ask that you answer honestly!

I will add a bit of propaganda under a cut on each poll, but please feel free to reblog polls and add your own! If you want your fav(s) to win, these polls need to be seen by lots of people!

I do encourage people to not vote blindly. Look at the photos, read the propaganda, maybe even do your own research before you decide how you feel about an animal!

And lastly, please keep things civil! We all have different tastes and someone hating your fav is not a personal affront against you!

That being said, we do not “Kill it with fire” here. It’s ok to not like an animal, but we do not tolerate people calling for violence against a species or wishing a whole species extinct.

Important Tags:

#Animal Polls: All main polls

#Special Poll: Any extra polls

#Statistics: A stats post will be posted after each round

#Asks: for any responses to asks (my askbox is open!)

#FAQ: for questions that may come up often

#Extras: for any extra posts or reblogs (I may want to infodump about my favs ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. I may also reblog other peoples’ propaganda!)

Round 1 will start September 1st!

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my absolute favorite art/science collaborations in the world is a project by National Geographic and photographer Joel Sartore called the Photo Ark. The ark is a 25 year project with the goal of photographing every animal species in human care, with the hopes of saving as many endangered species as possible. The Ark turned 18 years old today and they’ve just photographed their 16,000th animal- the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander!

I really recommend any animal lovers or photography enthusiasts learn about this project and follow photographer Joel Sartore on this journey. He does an incredible job of highlighting lesser known species and his skill as an artist is staggering. The behind the scenes process of how he gets these shots of such a wide variety of species is always a technical marvel.

Also worth noting that if you’re an artist ever in need of reference photos for an obscure animal species, this is a great resource where you can look up high quality images by species name! Anyone looking to decorate their home with a focus on biology art can purchase beautiful animal prints while supporting conservation.

Here are some of my favorite shots over the years to celebrate the Ark’s birthday!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Apatemyids were a group of unique early placental mammals that lived during the first half of the Cenozoic, known from North America, Europe, and Asia. Due to their specialized anatomy their evolutionary relationships are rather murky (they were traditionally part of the convoluted mess that was "Insectivora"), but currently they're thought to be a very early offshoot of the Euarchontoglires, the branch of placentals that includes modern rodents, lagomorphs, treeshrews, colugos, and primates.

Living in what is now western Europe during the mid-Eocene, around 47 million years ago, Heterohyus nanus was a small apatemyid about 30cm long (~12") – although just over half of that length was made up of its tail.

Like other apatemyids it had a proportionally big boxy head, with large forward-pointing rodent-like incisors in its lower jaw and hooked "can-opener-shaped" incisors in its upper jaw.

Example of an apatemyid skull from the closely related American genus Sinclairella. From Samuels, Joshua X. "The first records of Sinclairella (Apatemyidae) from the Pacific Northwest, USA." PaleoBios 38.1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.5070/P9381053299

The rest of its body was rather slender, and fossils with soft tissue preservation from the Messel Pit in Germany show that it had a bushy tuft of longer fur at the end of its long tail.

But the most distinctive feature of apatemyids like Heterohyus were their fingers, with highly elongated second and third digits resembling those of modern striped possums and aye-ayes. This suggests they had a similar sort of woodpecker-like ecological role, climbing around in trees using their teeth to tear into bark and expose wood-boring insect holes, then probing around with their long fingers to extract their prey.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

References:

Kalthoff, D. C., W. Von Koenigswald, and C. Kurz. "A new specimen of Heterohyus nanus (Apatemyidae, Mammalia) from the Eocene of Messel (Germany) with unusual soft part preservation." Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 252 (2004): 1-12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263714512_A_new_specimen_of_Heterohyus_nanus_Apatemyidae_Mammalia_from_the_Eocene_of_Messel_Germany_with_unusual_soft-part_preservation

Koenigswald, W. V., and H-P. Schierning. "The ecological niche of an extinct group of mammals, the early Tertiary apatemyids." Nature 326.6113 (1987): 595-597. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232761846_The_ecological_niche_of_early_Tertiary_apatemyids_-_extinct_group_of_mammals

Samuels, Joshua X. "The first records of Sinclairella (Apatemyidae) from the Pacific Northwest, USA." PaleoBios 38.1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.5070/P9381053299

Silcox, Mary T., et al. "Cranial anatomy of Paleocene and Eocene Labidolemur kayi (Mammalia: Apatotheria), and the relationships of the Apatemyidae to other mammals." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 160.4 (2010): 773-825. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00614.x

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cape grysbok Raphicerus melanotis

Observed by renehodges, CC BY-NC

167 notes

·

View notes

Video

Tiny moorhen chick having its first little swim!

80K notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching Przewalski's horses run free on the Kazakhstan steppe for the first time in 200 years

73K notes

·

View notes