Text

“what’s the song of the summer” ?? it’s DANCING IN THE DARK by bruce springsteen for the 40th year in a row

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

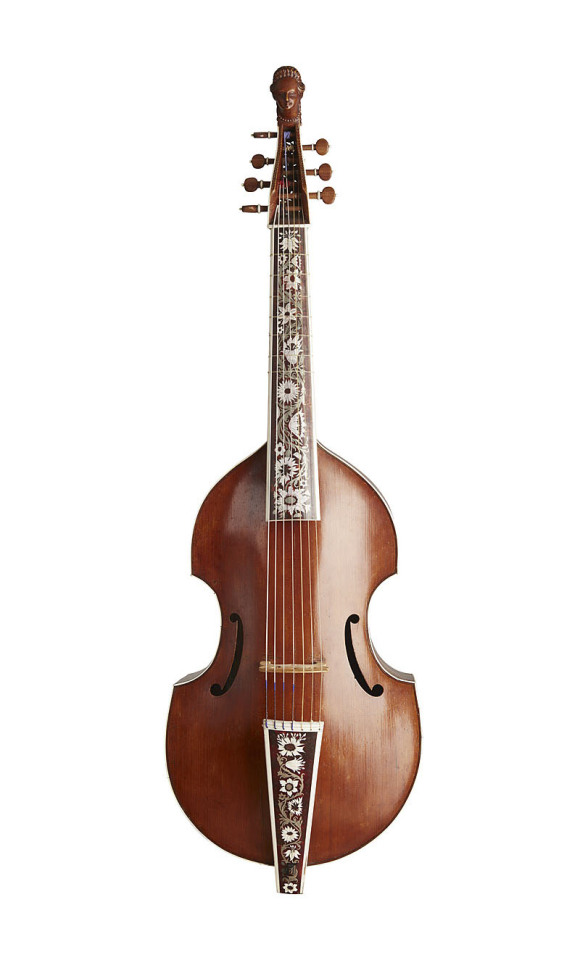

Joachim Tielke, musical instruments, 1688–1703. 1/ 2 Viola da Gamba 3/ Bell cistern 4/ Guitar 5/ Angelique 6/ Viola da gamba, seven strings. Hamburg, Germany. Via MKG

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dutch Delft tiles with various types of ships, Netherlands, around 1660

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

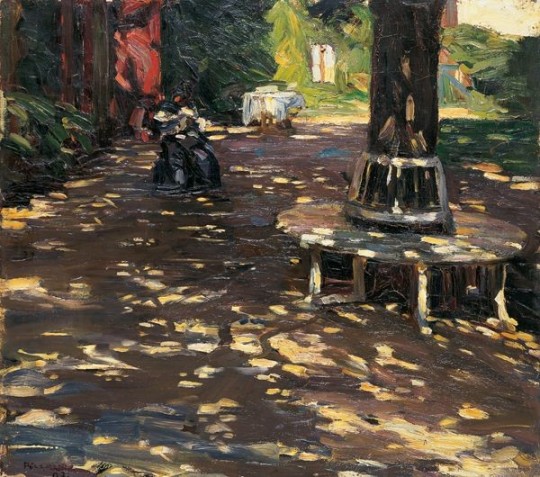

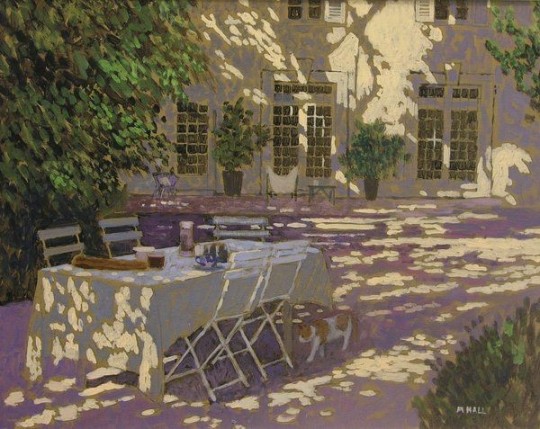

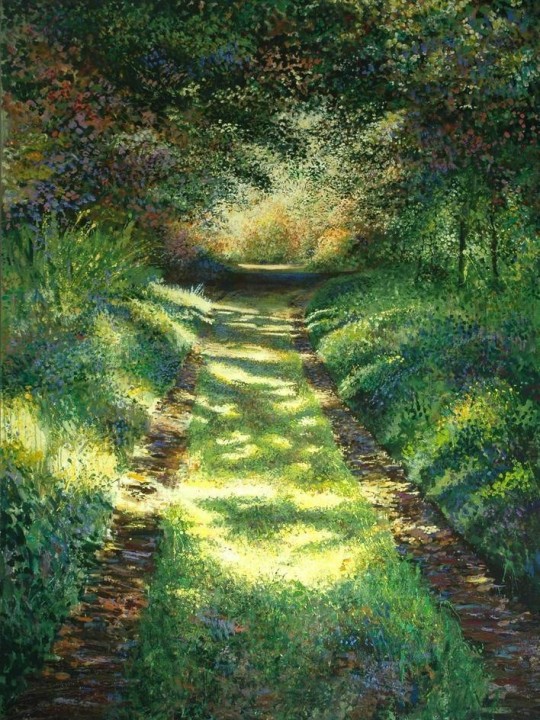

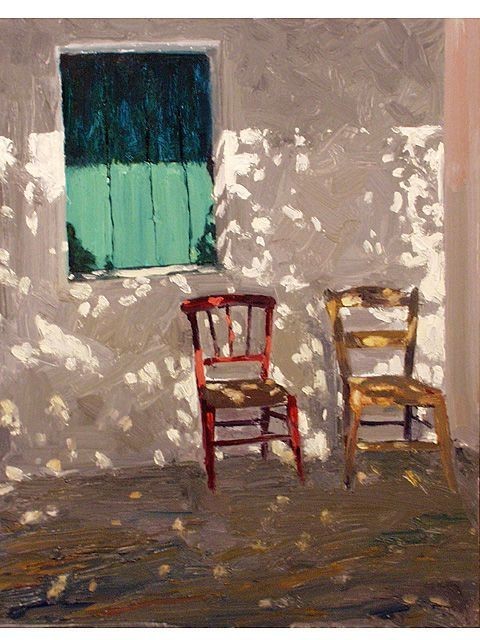

I cannot express how much I adore dappled shadows formed by sunlight in paintings and photography and in real life

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, hey, hey, ich war der goldene Reiter. Hey, hey, hey, ich bin ein Kind dieser Stadt.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hugh Mangum’s portrait subjects don’t seem afraid of his camera. Some gaze out with naked directness; others smile, laugh, and vogue, peering coyly from behind hats or newspapers. Walking around the Nasher exhibit, I found it difficult to look away. Mangum’s photographs, taken between 1897 and 1922, compose a broad yet intimate survey of society at the time, cutting across race, class, and gender lines. They feel startlingly alive and contemporary, as if a wall between past and present had splintered. At a time when photography had a reputation for being a stiff, solemn medium governed by strict social codes, Mangum’s unorthodox eye and practice captured a remarkable, seldom-seen side of life in the Jim Crow South.

When he died in 1922, Mangum was relatively unknown. A lanky white man with a wild, sloping mustache, he ran a portraiture operation as rakish as his grooming. He traveled between towns reachable by rail from Durham, setting up cheap portrait studios that he advertised with the slogan “All Kinds of Pictures.” A prolific photographer, he saved many of his glass-plate negatives, but he rarely dated or labeled them. At the time of his death, his box of negatives — almost one thousand in total — were left in his family’s tobacco barn in Durham, where he had maintained a small darkroom.

The pictures would remain there for almost fifty years, buried beneath junk, dirt, and chicken shit. Developers bought the homestead in the 1970s with the intention of building condominiums; the bulldozers were already on the property when conservation efforts championed by the activist Margaret Nygard saved the property, and the pictures on it, from being destroyed.

Many of the pictures were moved to the Duke Special Collections Library, where they were scanned and made digitally available; now, they are gaining a wider audience, thanks to Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922, an exhibit of Mangum’s photographs on view at the Nasher through May 19, and two new books celebrating them. Where We Find Ourselves, an accompanying catalog by Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris, who also curated the Nasher exhibit, was released in February; Photos Day or Night: The Archive of Hugh Mangum, by Sarah Stacke, was released in January.

The oldest of five children, Mangum was born in 1877, less than a decade after Durham was incorporated. Farming and factory work were the most obvious career routes, but, from an early age, Mangum preferred the visual arts. After studying art at Salem College in Winston-Salem, he taught himself photography and set up a studio in downtown Durham. Soon, however, he grew restless and took to traveling by rail through North Carolina and Virginia, setting up makeshift studios. While he would often return to Durham to visit his family, who lived along the Eno River in the McCown House (now preserved as part of the West Point on the Eno), his travels brought him into close proximity with a broad, diverse range of clientele. His massive traveling trunk, which now resides in a museum in the barn where his negatives were discovered, catalogs, in faint, unruly pencil, the many small towns he passed through.

While on the road, Mangum used a Penny Picture camera, which could take multiple exposures and allowed him to efficiently record between six and twenty-four images on a single glass plate negative. These negatives form a fascinating side-by-side record of everyone who walked into his studio, suggesting that it was not segregated, as other businesses of the time would have been. (Mangum took his first Penny Picture only a year before the Wilmington Race Riots, an incident that ushered in a violent new era of segregation and affirmed the grip of white supremacy on the state.) Many of Mangum’s subjects would have been born prior to emancipation. In researching the archive, one of the portraits that struck Sartor the most was a steely, guarded Cornelia Smith Fitzgerald, the grandmother of activist Pauli Murray, who was born in slavery.

While some public figures can be identified — Washington Duke, for instance — the majority of the pictures are of unidentified working-class people who would have saved up for a photograph, and for whom being photographed was a significant occasion. The contemporary challenge is how to be seen among countless pictures, but historical portraiture faced a steeper one: that of accurately representing a subject’s humanity in a rare — sometimes even once-in-a-lifetime — portrait. It is telling that, in the 1900 U.S. Census, rather than listing his occupation as a photographer, Mangum put down “artist.”

“He was a genuinely very serious, very talented artist. Making a portrait is really hard,” Sartor says. “He wasn’t working in a studio setting where the light was always something he could define the way he wanted to. He’s working a new situation every time he sets up his camera.”

The pictures at the Nasher are disarming for many reasons, but their candid quality is one of the strongest — the group shots, in particular, have the spontaneous quality of a photo booth at a bar. Girls clasp each other joyfully, clowning and intimate; one woman poses on a bike, a man poses with a guitar. Animals are included in many of the portraits, and in one strip, wedged between single shots of solemn looking men, a golden retriever poses, its tongue lolling patiently.

Time and serendipity have also played a radical hand in this archive. Because the pictures were stored in less-than-ideal conditions — a moldering tobacco barn by a river — they crack and speckle with emulsion, ghostly effects that somehow seem to reinforce the historical pathos of the images rather than mar it. These scars are preserved in the exhibit, and to see them blown up underscores the magic of these pictures’ survival. In some of the negatives, the panels have fused, giving the effect of subjects creeping from frame to frame.

“It appears almost as if people are sitting together, when in fact, he’s photographed them separately,” Harris says. “In his work, these worlds merge in a beautiful way.”

Some pictures are double exposed; in one of the most compelling portraits, a young white woman and a young black woman are overlaid, their gazes direct and uncompromising. A trained hypnotist, Mangum seemed to have a hypnotic gift for making his subjects feel both candid and seen, and his archive has just as hypnotic a grip on the present. In one picture, a baby stares out warily from her bassinet as a hand reaches into the frame to steady her. This is indicative of Mangum’s general approach to photography, letting life intervene, with results that are by turns lively, emotional, a little mysterious, and deeply humane.

“We could have done an edit where, in every picture, Mangum has made people comfortable, they’re laughing or responding to him,” Harris says, “[But] we found ourselves drawn to pictures where it’s not about Mangum’s presence. It’s about an atmosphere that’s created where the person kind of goes inside. You have some kind of sense of this interior light, interior thought. We were haunted by these.”

Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897–1922

Through Sunday, May 19

Nasher Museum of Art, Durham

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red velvet dress, 1886, Swedish.

By Augusta Lundin.

Worn by Wilhelmina von Hallwyl at the wedding of her daughter Ebba.

Hallwylska museet.

361 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anna Pavlova Dressed in costume for The fairy doll - photograph by Matzene Studio - c. possibly 1916

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marchesa Geronima Spinola by Anthony van Dyck, circa 1624.

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Benoît Agnès Trioson (1797)

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767–1824)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

ab. 1785 Suit (coat, waistcoat, breeches) (France)

silk velvet, silk satin, silver colored metal thread, silk

(Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin)

410 notes

·

View notes

Text

"you should be at the club" i should be in the woods. performing the ritual.

25K notes

·

View notes