Text

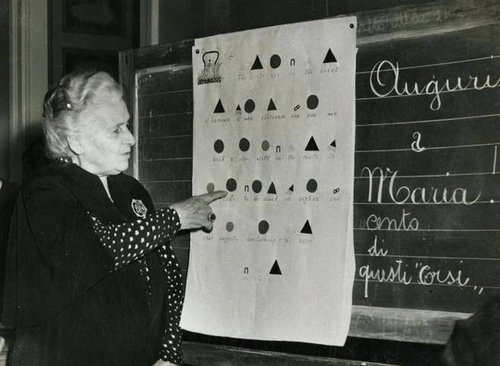

Maria Montessori

“Do not tell them how to do it. Show them how to do it and do not say a word. If you tell them, they will watch your lips move. If you show them, they will want it to do it themselves.”

Montessori’s Life

Maria Montessori was born on August 31, 1870, in the provincial town of Chiaravalle, Italy, to middle-class, well-educated parents. Her father, Alessandro Montessori, 33 years old at the time, was an official of the Ministry of Finance working in the local state-run tobacco factory. Her mother, Renilde Stoppani, 25 years old, was well educated for the times and was the great-niece of Italian geologist and paleontologist Antonio Stoppani.

When she was 12, her parents moved to Rome and encouraged her to become a teacher, the only career open to women at the time. While she did not have any particular mentor, she was very close to her mother who readily encouraged her. She also had a loving relationship with her father, although he disagreed with her choice to continue her education.

She was first interested in mathematics, and decided on engineering, but eventually became interested in biology and finally determined to enter medical school. Facing her father's resistance but armed with her mother's support, Montessori went on to graduate with high honors from the medical school of the University of Rome in 1896. In so doing, Montessori became the first female doctor in Italy.

On March 31, 1898, her only child – a son named Mario Montessori was born. Mario Montessori was born out of her love affair with Giuseppe Montesano, a fellow doctor who was co-director with her of the Orthophrenic School of Rome.

Montessori died of a cerebral hemorrhage on May 6, 1952, at the age of 81 in Noordwijk, South Holland, Netherlands, receiving in her later years’ honorary degrees and tributes for her work throughout the world.

Montessori’s Careers

From 1896 to 1901, Montessori worked with and researched so-called "phrenasthenic" children—in modern terms, children experiencing some form of mental retardation, illness, or disability. She also began to travel, study, speak, and publish nationally and internationally, coming to prominence as an advocate for women's rights and education for mentally disabled children.

Montessori continued with her research at the University's psychiatric clinic, and in 1897 she was accepted as a voluntary assistant there. As part of her work, she visited asylums in Rome where she observed children with mental disabilities, observations which were fundamental to her future educational work. She also read and studied the works of 19th-century physicians and educators Jean Marc Gaspard Itard and Édouard Séguin, who greatly influenced her work. Also in 1897, Montessori audited the University courses in pedagogy and read "all the major works on educational theory of the past two hundred years".

In 1897 Montessori spoke on societal responsibility for juvenile delinquency at the National Congress of Medicine in Turin. In 1898, she wrote several articles and spoke again at the First Pedagogical Conference of Turin, urging the creation of special classes and institutions for mentally disabled children, as well as teacher training for their instructors. She joined the board of the National League and was appointed as a lecturer in hygiene and anthropology at one of the two teacher-training colleges for women in Italy.

Montessori became the director of the Orthophrenic School for developmentally disabled children in 1900. There she began to extensively research early childhood development and education. Montessori began to conceptualize her own method of applying their educational theories, which she tested through hands-on scientific observation of students at the Orthophrenic School. Montessori found the resulting improvement in students' development remarkable. She spread her research findings in speeches throughout Europe, also using her platform to advocate for women's and children's rights.

Montessori was named director of the State Orthophrentic School in 1889. She worked with the children there for two years. All-day she taught in the school and then worked preparing new materials, making notes and observations and reflecting on her work. These two years she regarded as her "true degree" in education. To her amazement, she found these children could learn many things that had seemed impossible. This conviction led Montessori to devote her energies to the field of education for the remainder of her life.

Montessori’s Contributions to Education

The Montessori Method

In her book she outlines a typical winter's day of lessons, starting at 09:00 am and finishing at 04:00 pm:

9–10. Entrance. Greeting. Inspection as to personal cleanliness. Exercises of practical life; helping one another to take off and put on the aprons. Going over the room to see that everything is dusted and in order. Language: Conversation period: Children give an account of the events of the day before. Religious exercises.

10–11. Intellectual exercises. Objective lessons interrupted by short rest periods. Nomenclature, Sense exercises.

11–11:30. Simple gymnastics: Ordinary movements done gracefully, the normal position of the body, walking, marching in line, salutations, movements for attention, placing of objects gracefully.

11:30–12. Luncheon: Short prayer.

12–1. Free games.

1–2. Directed games, if possible, in the open air. During this period the older children, in turn, go through with the exercises of practical life, cleaning the room, dusting, putting the material in order. General inspection for cleanliness: Conversation.

2–3. Manual work. Clay modeling, design, etc.

3–4. Collective gymnastics and songs, if possible in the open air. Exercises to develop forethought: Visiting, and caring for, the plants and animals.

She felt by working independently children could reach new levels of autonomy and become self-motivated to reach new levels of understanding. Montessori also came to believe that acknowledging all children as individuals and treating them as such would yield better learning and fulfilled potential in each particular child. She began to see independence as the aim of education, and the role of the teacher as an observer and director of children's innate psychological development.

She also knew that, in order to consider these developments as representing universal truths, she must study them under different conditions and be able to reproduce them. In this spirit that same year, a second school was opened in San Lorenzo, a third in Milan, and a fourth in Rome in 1908, the latter for children of well-to-do parents. By 1909, all of Italian Switzerland began using Montessori's methods in their orphan asylums and children's houses.

Word of Montessori's work spread rapidly. Visitors from all over the world arrived at the Montessori schools to verify with their own eyes the reports of these "remarkable children." Montessori began a life of world travel - establishing schools and teacher training centers, lecturing, and writing. The first comprehensive account of her work, The Montessori Method, was published in 1909.

In 1915, Montessori returned to Europe and took up residence in Barcelona, Spain. Over the next 20 years, Montessori traveled and lectured widely in Europe and gave numerous teacher training courses. Montessori education experienced significant growth in Spain, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

Montessori’s Significant Awards & Legacy

In 1949, the first training course for birth to three years of age, called the Scuola Assistenti all'infanzia (Montessori School for Assistants to Infancy) was established. She was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Montessori was also awarded the French Legion of Honor, Officer of the Dutch Order of Orange Nassau, and received an Honorary Doctorate of the University of Amsterdam. In 1950 she visited Scandinavia, represented Italy at the UNESCO conference in Florence, presented at the 29th international training course in Perugia, gave a national course in Rome, published a fifth edition of Il Metodo with the new title La Scoperta del Bambino (The Discovery of the Child), and was again nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1951 she participated in the 9th International Montessori Congress in London, gave a training course in Innsbruck, was nominated for the third time for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Maria Montessori and Montessori schools were featured on coins and banknotes of Italy, and on stamps of the Netherlands, India, Italy, Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Montessori’s Works & Writings

Montessori published a number of books, articles, and pamphlets during her lifetime, often in Italian, but sometimes first in English. However, many of her later works were transcribed from her lectures, often in translation, and only later published in book form.

Montessori's major works are given here in order of their first publication, with significant revisions and translations:

(1909) Il Metodo della Pedagogia Scientifica applicato all'educazione infantile nelle Case dei Bambini

revised in 1913, 1926, and 1935; revised and reissued in 1950 as La scoperta del bambino

(1912) English edition: The Montessori Method: Scientific Pedagogy as Applied to Child Education in the Children's Houses

(1948) Revised and expanded English edition issued as The Discovery of the Child

(1950) Revised and reissued in Italian as La scoperta del bambino

(1910) Antropologia Pedagogica

(1913) English edition: Pedagogical Anthropology

(1914) Dr. Montessori's Own Handbook

(1921) Italian edition: Manuale di pedagogia scientifica

(1916) L'autoeducazione nelle scuole elementari

(1917) English edition: The Advanced Montessori Method, Vol. I: Spontaneous Activity in Education; Vol. II: The Montessori Elementary Materia

(1922) I bambini viventi nella Chiesa

(1929) English edition: The Child in the Church, Maria Montessori’s first book on the Catholic liturgy from the child’s point of view.

(1923) Das Kind in der Familie (German)

(1929) English edition: The Child in the Family

(1936) Italian edition: Il bambino in famiglia

(1934) Psico Geométria (Spanish)

(2011) English edition: Psychogeometry

(1934) Psico Aritmética

(1971) Italian edition: Psicoaritmetica

(1936) L'Enfant(French)

(1936) English edition: The Secret of Childhood

(1938) Il segreto dell'infanzia

(1948) De l'enfant à l'adolescent

(1948) English edition: From Childhood to Adolescence

(1949) Dall'infanzia all'adolescenza

(1949) Educazione e pace

(1949) English edition: Peace and Education

(1949) Formazione dell'uomo

(1949) English edition: The Formation of Man

(1949) The Absorbent Mind

(1952) La mente del bambino. Mente assorbente

(1947) Education for a New World

(1970) Italian edition: Educazione per un mondo nuovo

(1947) To Educate the Human Potential

(1970) Italian edition: Come educare il potenziale umano

1 note

·

View note