20 | any pronouns | history and archaeology student | my hobbies include horse | dni if you're afraid of clowns

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

145K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jerry suspects the oracle might be flirting with him. Elaine attempts to break up with a chariot racer by joining the vestal virgins. Kramer makes raunchy pottery. George refuses to believe that he has been cursed.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

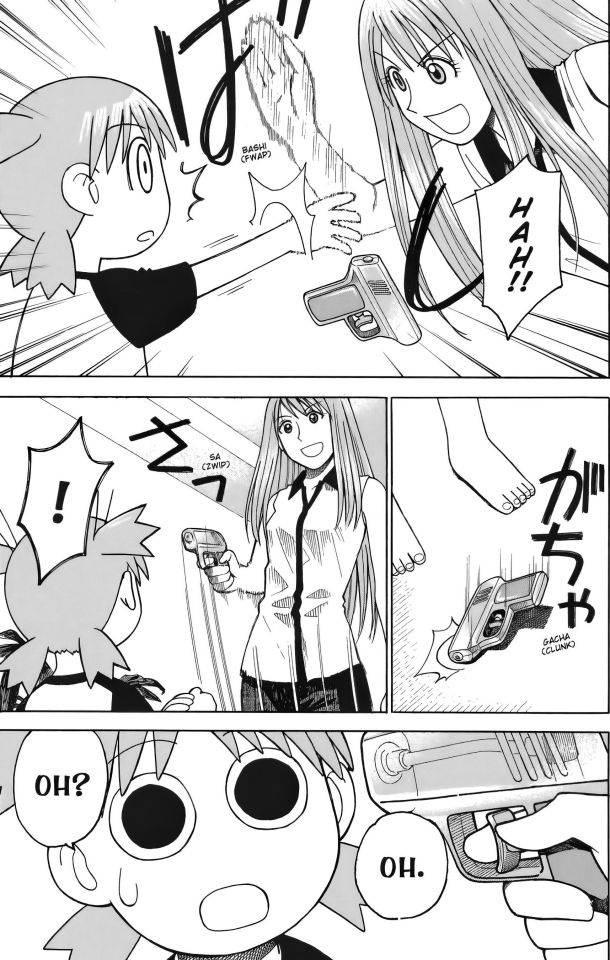

if chapter 4 did anything its that it reminded me how zooted she is for the lizard

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

Speef is real to me. I'm sorry for that.

42K notes

·

View notes

Text

Asking "was ancient greek alchemy a religion, a science, or magic" is like asking "Was Khosrow II, last emperor of the Sassanians, a democrat, a republican, or independent?"

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I must say, Steven Universe is a lot more enjoyable when you don't need to read through a heaping helping of Tumblr discourse about who's secretly abusing whom this week.

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

have this other jolene painting that I'm not gonna finish

700 notes

·

View notes

Text

References

[1] David Atkinson, “The English Revival Canon: Child Ballads and the Invention of Tradition,” The Journal of American Folklore 114, no. 453 (2001): 370, https://doi.org/10.2307/542028.

[2] C. J. Bearman, “Who Were the Folk? The Demography of Cecil Sharp’s Somerset Folk Singers,” The Historical Journal 43, no. 3 (September 2000): 751, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X99001338.

[3] David Gregory, “The Reconstruction of a Cultural Identity: Nationalism, Gender, and Censorship in the Late Victorian Folksong Revival in England,” MUSICultures 37 (2010): 128, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/reconstruction-cultural-identity-nationalism/docview/926241257/se-2.

[4] Alun Howkins, “Greensleeves and the idea of national music,” in Patriotism: The Making and Unmaking of British National Identity: Volume III: National Fictions, ed. Raphael Samuel (London: Routledge, 1989), 90.

[5] Hubert Parry, “Inaugural Address,” Journal of the Folk-Song Society 1, no. 1 (1899): 3, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4433848?seq=1.

[6] Howkins, “Greensleeves and the idea of national music,” 90-91.

[7] Julian Onderdonk, and Ceri Owen, eds, Vaughan Williams in Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024), 137, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108681261.

[8] Michael Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2022), 58, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003307242.

[9] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 9.

[10] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 1.

[11] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 1.

[12] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 9.

[13] Robert Colls, and Philip Dodd, Englishness: Politics and Culture 1880-1920, (London: Croom Helm, 1986), 64.

[14] J. A. Hobson, Imperialism, 2nd ed. (London: Alley and Unwin, 1902), 150-51.

[15] Colls and Dodd, Englishness, 67; Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 8.

[16] Graham Freeman, “‘It Wants All the Creases Ironing Out’: Percy Grainger, the Folk Song Society, and the Ideology of the Archive,” Music & Letters 92, no. 3 (2011): 412, https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcr075.

[17] Colls and Dodd, Englishness, 62-63.

[18] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 60; Gregory, “The Reconstruction of a Cultural Identity,” 142; Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 1.

[19] Colls and Dodd, Englishness, 75, 80.

[20] Simon Heywood, “Informant Disavowal and the Interpretation of Storytelling Revival,” Folklore 115, no. 1 (1 April 2004): 60, https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587042000192529.

[21] John Francmanis, “National Music to National Redeemer: The Consolidation of a “Folk-Song” Construct in Edwardian England,” Popular Music 21, no. 1 (2002): 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143002002015.

[22] Francmanis, “National Music to National Redeemer,” 1–2.

[23] Howkins, “Greensleeves and the idea of national music,” 89.

[24] Howkins, “Greensleeves and the idea of national music,” 89.

[25] David Harker, Fakesong: The Manufacture of British Folksong 1700 to the Present Day (Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1985), 144.

[26] Onderdonk and Owen, eds, Vaughan Williams in Context, 144.

[27] Joseph Williams, England’s Folk Revival and the Problem of Identity in Traditional Music (London: Routledge, 2022), 60, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367648145.

[28] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 3.

[29] Atkinson, “The English Revival Canon,” 378.

[30] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 2; Atkinson, “The English Revival Canon,” 372-73.

[31] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 3.

[32] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 1.

[33] Williams, England’s Folk Revival and the Problem of Identity in Traditional Music, 36.

[34] Freeman, “‘It Wants All the Creases Ironing Out,’” 432.

[35] Sabine Baring-Gould, Henry Fleetwood Sheppard, and Frederick William Bussell, Songs and Ballads of the West: A Collection Made from the Mouths of the People, 5th ed. (London: Methuen, 1913), x.

[36] Onderdonk and Owen, eds, Vaughan Williams in Context, 124.

[37] Ralph Vaughan Williams, “Preface,” Journal of the Folk-Song Society 8, no. 35 (1931): iii, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4434232?seq=1.

[38] Francmanis, “National Music to National Redeemer,” 5.

[39] Ralph Vaughan Williams, “A School of English Music,” in Vaughan Williams on Music, ed. David Manning (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 34.

[40] Onderdonk and Owen, eds, Vaughan Williams in Context, 145.

[41] Freeman, “‘It Wants All the Creases Ironing Out,’” 431.

[42] Ralph Vaughan Williams, “Lucy Broadwood: An Appreciation,” Journal of the Folk-Song Society 8, no. 31 (1927): 44-45.

[43] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 178.

[44] Parry, “Inaugural Address,” 2.

[45] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 2.

[46] Freeman, “‘It Wants All the Creases Ironing Out,’” 413.

[47] Gregory, “The Reconstruction of a Cultural Identity,” 137.

[48] Gregory, “The Reconstruction of a Cultural Identity,” 137.

[49] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 8.

[50] Brocken, The British Folk Revival, 9.

[51] Francmanis, “National Music to National Redeemer,” 13.

[52] Francmanis, “National Music to National Redeemer,” 12-14.

How did the Folk-Song Society contribute to the construction of a national musical identity for Britain?

The first British folk revival was a period of intense interest in the study of so-called “folk music” and “folk song” in the late 19th and early 20th century.[1] Prior to World War I, this revival was among the most important influences of the time on English cultural life and at the forefront of the movement was the Folk-Song Society.[2] The Journal of the Folk-Song Society was published from 1898-1931, the perceived necessity of which I argue represents a peak in attention to English folk music. The Society undertook the task of recovering and recording music from those who claimed to know them, translating an oral tradition to written form and overseeing the transformation of localised folk song collecting into a nation-wide cultural movement. The Folk-Song Society was integral to the formulation of a musical identity and aesthetic for Britain based on an imagined rural southern England as representative of a past age of nationalist, collective, and moral English greatness. I come to this conclusion by examining the industrial, globalised, and consumerist modernity which the folk revival arose in response to, as well as the intellectual trends on which it is based. I then elaborate on the politics of the Society itself, and how the folk music canon on which the revival both constructed and is based on is an amalgamated, romanticised, and inaccurate representation of rural England with specific political consequences. Thus, “folk music” is nigh impossible to define as it does not represent a cohesive group. Throughout this essay it simply refers to the collection of songs popularised by the revival.

In addition to being a response to the perceived indecency of cities, the first British folk revival also emerged due to a sense of musical inferiority in comparison to continental Europe. As late as the 1880s it was fashionable to decry England as “a land with no music.”[3] Artists saw English culture as dominated by foreign compositions and their influence on English composers, who were often seen as derivative of German and Austrian trends.[4] In an artistic scene which holds that “style is ultimately national,” England’s lack of identifiable style suggested a lack of national character or prestige.[5] The projected renaissance of English music was founded on two intertwined traditions: the first was that of previous formal musical prestige, by examining “the time of Charles I [when] music in England began to languish;” the second route lay through folk song.[6] These two traditions sought out roots for English music in a notably pre-industrial English society.

From the late 19th and early 20th centuries, developments in transportation allowed more affluent Londoners to commute from increasingly far, contributing to the expanding tide of suburbia and displacing rural working-class communities.[7] Meanwhile, Industrial capitalism had created an urban dystopia deeper within the cities themselves characterised by increased pollution, population density, and congestion.[8] Popular music was considered low-brow, commercialised, and without aesthetic value.[9] Its moral effect was commonly so rebuked that it was regarded as for “people who, for the most part have the most false ideals, or none at all - who are always struggling for existence,” suggesting the connection between moral character and the ability to access and appreciate music considered more artistic.[10] Described as “an enemy at the doors of folk-music which is driving it out,” popular music was regarded by many scholars, such as Hubert Parry, as irreconcilable with folk music.[11] Folk music was adopted in an attempt to preserve an apparently disappearing romanticised way of life diametrically opposed to the indecency of cities.[12] Furthermore, from the late 1870s, the industry which had created these now detested urban environments had gradually been losing ground to German and American manufacturing.[13] By 1902, England came to be perceived as a country of “plush parasitism,” increasingly defined by its colonial holdings and the associated reliance on them rather than national strength or independence.[14] Cities became associated with foreign influence, economic deterioration, and selfish entrepreneurship for individual (rather than noble and national) benefit. Cosmopolitan (foreign) and industrialised (dirty) landscapes came to represent the decaying core of the British Empire, while rural England was regarded as an antidote to modern inauthenticities.[15] A key emphasis here is on the concept of restoration; In contrast to contemporaneous modernist movements which in response to similar societal problems promoted the rejection of the past to create a new future, the folk revival aimed to improve England and its people by elements of a mythologised past to reclaim its glory in the modern age. These elements were believed to be unwittingly preserved by the rural English, who supposedly lived unexposed to contaminating modern and global influences. English folk song, therefore, represented a nationalist aesthetic discourse through which the English elites of the Folk-Song Society aimed to address questions of social reform.[16]

From the late 19th century, the landscape of rural southern England became increasingly important to constructions of English national identity. The majority of England’s population had lived in urban environments since 1861.[17] By musically and aesthetically locating the nation in the rural “south country” through regionally specific features such as thatched rooves, village greens, and hedgerows, the “essence” of the nation is placed outside the daily experience of the majority of English, let alone British, people. The glorification of “folk culture” by the Society masked the reality of rural existences; themes of stark poverty, labour, suffering, crime, and sexuality were either stylised or completely ignored to maintain the ideal that folk music had “nothing in it common or unclean.”[18] By associating England with the south country, “real” English society was also given a model of social formation with a “natural” society of rank and inequality.[19] This England, although socially and economically hierarchical, was built on themes of continuity and inter-class unity and obligation. While Simon Heywood argues that folk revivals should more logically be viewed as a “superficially ideological display for underlying aesthetic purposes,” he neglects to consider why revived things may be “intrinsically attractive and artistically potent.”[20] While there is certainly room to consider simple aesthetic appeal on an individual level, the widespread captivation by romanticised rural and quasi-historical England that the folk revival represents begs the question of why the material selected to be revived is considered powerful, appealing, or important at that given moment.

The notions of national culture popular amongst the Folk-Song Society originated from prior European musical theory. Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) contended that isolation from international influence enabled peasant populations to form distinct cultures.[21] Herder came to believe that this oral tradition contained the essence of a nation’s character and therefore that for the high culture of a nation to be unifying, it must be rooted in the modes of peasantry.[22] The sounds of music expressed the soul, and that this soul was (at least in part) national.[23] This idea became an integral part of national movements throughout Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[24] Concurrently, the nascent field of music history held a growing preoccupation with Darwinian theories of evolution.[25] Victorian music historians believed that Western music had developed in complexity over time, suggesting that the production of music evolved in some way.[26] Cecil Sharp, a prominent figure of the revival, furthered these ideas in his work English Folk Song: Some Conclusions by proposing that folk music was constantly evolving to reflect national characteristics and ideals through a collective, unconscious process in which the nation itself could be thought of as the author.[27] He suggested that “true style comes not from the individual but from the products of crowds of fellow-workers, who sift, and try, and try again, till they have found the thing that suits their native taste.”[28] This negatively impacted the agency of rural people, reducing their creative role to unwitting outlets for a national process beyond their control.

While the work of the Folk-Song Society ostensibly consisted of simply collecting materials and making them accessible, the processes of recording and publication led to the Society effectively determining who the “folk” in question were, what they produced, and what they represented. Traditional singing had never adhered to a stable canon, nor set of lyrics or melody, yet the Folk-Song Society seemed determined to identify a singular tradition from the diversity of England.[29] Despite the acknowledgement that “English tunes are not marked by such characteristic traits of melody and rhythm,” making it “almost impossible to take down folk-songs with certainty,” the Folk-Song Society in consensus insisted on the existence of a cohesive English folk song tradition.[30] In practice, this could only be identified through compatibility with the Society’s own established canon and understanding of said tradition. In electing themselves the arbitrators of musical value and categorisation, the Folk-Song Society entered into a paternalistic relationship with folk music’s performers. The Society was founded partly on the premise that there was a need “to save something primitive and genuine from extinction,” prioritising a need to record and catalogue over engagement with the people and associated way of life they glorified.[31] Hubert Parry, at the inauguration of the Folk-Song Society, emphasised that “these treasures of humanity [folk songs] are getting rare, for they are written… upon the sensitive brain fibres of those who learn them and have but little idea of their value.”[32] The “folk” were simultaneously celebrated as the bearers of an invaluable cultural heritage and denigrated as an unconscious mass who threatened the survival of their own musical legacy.[33]

Furthermore, by frequently publishing collected songs without acknowledgement of the collector’s source, folk music was frequently presented as a raw, unowned resource in which individuals did not make artistic decisions. Folk music was instead the natural, unpersonalised product of evolutionary development, without the protection of any assertion to private or intellectual property or right.[34] Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould (a member of the Society) believed that songs that were shown to have been written by singers of folk music were “musically worthless” because “the yokel is as incapable of creating a beautiful melody as he is of producing a beautiful sculpture, or of composing a genuine poem.”[35] However, these views were not universal within the Society: Ralph Vaughan Williams believed individual artistry underlay many elements of folk performance.[36] On the other hand, by describing undiscovered folk songs as “some vein of precious metal waiting to be discovered” in the Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Vaughan Williams also expressed and perpetuated the idea that folk songs represent an inert, harvestable resource, waiting to be extracted and refined by the English elite.[37] The Folk-Song Society repositioned folk song as something that, although produced by rural people, is the inheritance and right of all citizens. If the act of collection in the revival was intended to preserve material for the creation of a new and better England, this betterment is characterised by the extraction and translation or “elevation” of folk music to forms primarily associated with and consumed by the middle and upper classes.[38]

Regardless of the beliefs of individual Society members, their contributions to the Journal of the Folk-Song Society strengthened an ethnonationalist movement. In 1902, Vaughan Williams questioned why an English composer should attempt to found a style of music on “a class to which he does not belong, and which itself no longer exists,” referring to the peasants that were said by Herder to express the soul of the nation.[39] He later became one of the most prominent figures in the folk revival. Vaughan Williams also held the term “Merrie England” and its associated historical inaccuracies in contempt, yet he held a strong conviction importance of the cultural achievements of the folk and late Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean periods as a model for contemporary English artists, aesthetics which are also characteristic of Merrie England.[40] According to Graham Freeman, Vaughan Williams's suppression of his interest in the possibility of individual artistic expression in favour of “ironed-out” songs for the Journal cannot be seen as anything other than an ideological concession.[41] Similarly, according to Vaughan Williams, Lucy Broadwood “never, if she could help it, used the word "folk song,” and felt it a “betrayal of trust” to bring the songs “into the glaring light of the concert room and theatre, or to make them a cog in the educational wheel.”[42] Broadwood was an integral figure of the Folk-Song Society, being among its founding committee members and serving as its Editor and Honorary Secretary from 1904, remaining in her Editor position until 1926. Regardless, her misgivings about the consequences of the Society’s activities did not lead her to use her centrality within the Society to act on her moral concerns about the revival. While on its own, this could be attributed to Broadwood’s influence being limited by her position as a woman in a male-dominated organisation, in conjunction with Vaughan Williams' ideological conformity, it suggests that despite the apparent theoretical heterogeneity within the Folk-Song Society, individual grievances were suppressed.[43] The Journal remained united by a common nationalistic focus on folk song, intersecting with and independent of individual political affiliation.

The musical canon constructed by the Folk-Song Society lacked definable characteristics, making it vulnerable to redefinition and appropriation. Potentially as a result of the creation of the polemic relationship between folk songs and other popular music, in 1898 there emerged a perceived necessity “to distinguish what is genuine from what is emasculated.”[44] Revivalist logic had a tendency to discard the unknown and rely on perceived rational certainties to determine legitimacy, which were ultimately value judgements.[45] The conviction that folk music had a specific ethnonationalist origin led many collectors to edit and refine the songs they collected in an effort to cleanse them of “inauthentic” accretions, both lyrically and melodically. Censorship could also occur on the part of the performer.[46] Some singers practised self-censorship when performing for those they perceived as more refined than their usual audience, particularly if the collector was a member of the clergy or a woman, who both represented a significant proportion of collectors.[47] If an informant did deliver a song deemed unacceptable, the simplest solution for a publisher was to simply cut offending verses or entire songs.[48] Consequently, the canon of the folk revival was formed through a process of selection, exclusion and editing, the end product of which, if it could be linked to any form of identity, represented middle- and upper-class collectors rather than the people from whom they were collected.[49]

Prior to its construction by the Society, “Folk” music may never have existed, and that which was created should not be considered an essential expression. While it was understood as a lasting and “evolving” form of popular culture, many members of the Society failed to couple the continuity of folk music with the much despised popular songs favoured by their contemporary lower classes.[50] Folk music was detached from the melodies and depravity of the modern urban working class in order to preserve its sanctity in representing something other than the problematic modernity. However, in many country towns and villages, folk song had diminished in popularity.[51] It is precisely the decline of folk music that prompted many elites to fear the loss of a past way of life associated with English greatness and wholesomeness, but it also suggests that the accusations of appropriation from the working class commonly levelled against the Folk-Song Society are misguided. By propagating the understanding of folk song as essential to the character of a monolithic English working class, Marxist analyses such as that by David Harker perpetuate the nationalist and classist presumptions of the Society’s members rather than appreciating the dynamism and diversity of English geography. When folk music had been popular, it had not been catalogued and disseminated by state education but was about subjects which interested the singers and reflected their relevant socio-cultural context.[52] For the majority of rural England, this was no longer the case.

In conclusion, the Folk-Song Society contributed to the creation of a national musical identity in Britain through the selective and editorial translation of oral traditions throughout England to form an ethnonationalist identity that could be adopted by all British citizens. This identity was aesthetically centred on the southern English countryside and reinforced intertwined romanticised traditional values in response to the growing influence of foreign industry and culture, urbanisation, and racial understandings of the nation state. These findings represent but one chapter in the continuous negotiation of what it means to be English in a period when the members of the Society attempted to locate legitimate Englishness in a modernising world seemingly leaving Britain behind. As a result, they left a lasting impact on the study of folk music, the folk genre, and the aesthetic of the United Kingdom into the 21st century, while the music they deemed problematic remains in relative obscurity.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How did the Folk-Song Society contribute to the construction of a national musical identity for Britain?

The first British folk revival was a period of intense interest in the study of so-called “folk music” and “folk song” in the late 19th and early 20th century.[1] Prior to World War I, this revival was among the most important influences of the time on English cultural life and at the forefront of the movement was the Folk-Song Society.[2] The Journal of the Folk-Song Society was published from 1898-1931, the perceived necessity of which I argue represents a peak in attention to English folk music. The Society undertook the task of recovering and recording music from those who claimed to know them, translating an oral tradition to written form and overseeing the transformation of localised folk song collecting into a nation-wide cultural movement. The Folk-Song Society was integral to the formulation of a musical identity and aesthetic for Britain based on an imagined rural southern England as representative of a past age of nationalist, collective, and moral English greatness. I come to this conclusion by examining the industrial, globalised, and consumerist modernity which the folk revival arose in response to, as well as the intellectual trends on which it is based. I then elaborate on the politics of the Society itself, and how the folk music canon on which the revival both constructed and is based on is an amalgamated, romanticised, and inaccurate representation of rural England with specific political consequences. Thus, “folk music” is nigh impossible to define as it does not represent a cohesive group. Throughout this essay it simply refers to the collection of songs popularised by the revival.

In addition to being a response to the perceived indecency of cities, the first British folk revival also emerged due to a sense of musical inferiority in comparison to continental Europe. As late as the 1880s it was fashionable to decry England as “a land with no music.”[3] Artists saw English culture as dominated by foreign compositions and their influence on English composers, who were often seen as derivative of German and Austrian trends.[4] In an artistic scene which holds that “style is ultimately national,” England’s lack of identifiable style suggested a lack of national character or prestige.[5] The projected renaissance of English music was founded on two intertwined traditions: the first was that of previous formal musical prestige, by examining “the time of Charles I [when] music in England began to languish;” the second route lay through folk song.[6] These two traditions sought out roots for English music in a notably pre-industrial English society.

From the late 19th and early 20th centuries, developments in transportation allowed more affluent Londoners to commute from increasingly far, contributing to the expanding tide of suburbia and displacing rural working-class communities.[7] Meanwhile, Industrial capitalism had created an urban dystopia deeper within the cities themselves characterised by increased pollution, population density, and congestion.[8] Popular music was considered low-brow, commercialised, and without aesthetic value.[9] Its moral effect was commonly so rebuked that it was regarded as for “people who, for the most part have the most false ideals, or none at all - who are always struggling for existence,” suggesting the connection between moral character and the ability to access and appreciate music considered more artistic.[10] Described as “an enemy at the doors of folk-music which is driving it out,” popular music was regarded by many scholars, such as Hubert Parry, as irreconcilable with folk music.[11] Folk music was adopted in an attempt to preserve an apparently disappearing romanticised way of life diametrically opposed to the indecency of cities.[12] Furthermore, from the late 1870s, the industry which had created these now detested urban environments had gradually been losing ground to German and American manufacturing.[13] By 1902, England came to be perceived as a country of “plush parasitism,” increasingly defined by its colonial holdings and the associated reliance on them rather than national strength or independence.[14] Cities became associated with foreign influence, economic deterioration, and selfish entrepreneurship for individual (rather than noble and national) benefit. Cosmopolitan (foreign) and industrialised (dirty) landscapes came to represent the decaying core of the British Empire, while rural England was regarded as an antidote to modern inauthenticities.[15] A key emphasis here is on the concept of restoration; In contrast to contemporaneous modernist movements which in response to similar societal problems promoted the rejection of the past to create a new future, the folk revival aimed to improve England and its people by elements of a mythologised past to reclaim its glory in the modern age. These elements were believed to be unwittingly preserved by the rural English, who supposedly lived unexposed to contaminating modern and global influences. English folk song, therefore, represented a nationalist aesthetic discourse through which the English elites of the Folk-Song Society aimed to address questions of social reform.[16]

From the late 19th century, the landscape of rural southern England became increasingly important to constructions of English national identity. The majority of England’s population had lived in urban environments since 1861.[17] By musically and aesthetically locating the nation in the rural “south country” through regionally specific features such as thatched rooves, village greens, and hedgerows, the “essence” of the nation is placed outside the daily experience of the majority of English, let alone British, people. The glorification of “folk culture” by the Society masked the reality of rural existences; themes of stark poverty, labour, suffering, crime, and sexuality were either stylised or completely ignored to maintain the ideal that folk music had “nothing in it common or unclean.”[18] By associating England with the south country, “real” English society was also given a model of social formation with a “natural” society of rank and inequality.[19] This England, although socially and economically hierarchical, was built on themes of continuity and inter-class unity and obligation. While Simon Heywood argues that folk revivals should more logically be viewed as a “superficially ideological display for underlying aesthetic purposes,” he neglects to consider why revived things may be “intrinsically attractive and artistically potent.”[20] While there is certainly room to consider simple aesthetic appeal on an individual level, the widespread captivation by romanticised rural and quasi-historical England that the folk revival represents begs the question of why the material selected to be revived is considered powerful, appealing, or important at that given moment.

The notions of national culture popular amongst the Folk-Song Society originated from prior European musical theory. Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) contended that isolation from international influence enabled peasant populations to form distinct cultures.[21] Herder came to believe that this oral tradition contained the essence of a nation’s character and therefore that for the high culture of a nation to be unifying, it must be rooted in the modes of peasantry.[22] The sounds of music expressed the soul, and that this soul was (at least in part) national.[23] This idea became an integral part of national movements throughout Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[24] Concurrently, the nascent field of music history held a growing preoccupation with Darwinian theories of evolution.[25] Victorian music historians believed that Western music had developed in complexity over time, suggesting that the production of music evolved in some way.[26] Cecil Sharp, a prominent figure of the revival, furthered these ideas in his work English Folk Song: Some Conclusions by proposing that folk music was constantly evolving to reflect national characteristics and ideals through a collective, unconscious process in which the nation itself could be thought of as the author.[27] He suggested that “true style comes not from the individual but from the products of crowds of fellow-workers, who sift, and try, and try again, till they have found the thing that suits their native taste.”[28] This negatively impacted the agency of rural people, reducing their creative role to unwitting outlets for a national process beyond their control.

While the work of the Folk-Song Society ostensibly consisted of simply collecting materials and making them accessible, the processes of recording and publication led to the Society effectively determining who the “folk” in question were, what they produced, and what they represented. Traditional singing had never adhered to a stable canon, nor set of lyrics or melody, yet the Folk-Song Society seemed determined to identify a singular tradition from the diversity of England.[29] Despite the acknowledgement that “English tunes are not marked by such characteristic traits of melody and rhythm,” making it “almost impossible to take down folk-songs with certainty,” the Folk-Song Society in consensus insisted on the existence of a cohesive English folk song tradition.[30] In practice, this could only be identified through compatibility with the Society’s own established canon and understanding of said tradition. In electing themselves the arbitrators of musical value and categorisation, the Folk-Song Society entered into a paternalistic relationship with folk music’s performers. The Society was founded partly on the premise that there was a need “to save something primitive and genuine from extinction,” prioritising a need to record and catalogue over engagement with the people and associated way of life they glorified.[31] Hubert Parry, at the inauguration of the Folk-Song Society, emphasised that “these treasures of humanity [folk songs] are getting rare, for they are written… upon the sensitive brain fibres of those who learn them and have but little idea of their value.”[32] The “folk” were simultaneously celebrated as the bearers of an invaluable cultural heritage and denigrated as an unconscious mass who threatened the survival of their own musical legacy.[33]

Furthermore, by frequently publishing collected songs without acknowledgement of the collector’s source, folk music was frequently presented as a raw, unowned resource in which individuals did not make artistic decisions. Folk music was instead the natural, unpersonalised product of evolutionary development, without the protection of any assertion to private or intellectual property or right.[34] Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould (a member of the Society) believed that songs that were shown to have been written by singers of folk music were “musically worthless” because “the yokel is as incapable of creating a beautiful melody as he is of producing a beautiful sculpture, or of composing a genuine poem.”[35] However, these views were not universal within the Society: Ralph Vaughan Williams believed individual artistry underlay many elements of folk performance.[36] On the other hand, by describing undiscovered folk songs as “some vein of precious metal waiting to be discovered” in the Journal of the Folk-Song Society, Vaughan Williams also expressed and perpetuated the idea that folk songs represent an inert, harvestable resource, waiting to be extracted and refined by the English elite.[37] The Folk-Song Society repositioned folk song as something that, although produced by rural people, is the inheritance and right of all citizens. If the act of collection in the revival was intended to preserve material for the creation of a new and better England, this betterment is characterised by the extraction and translation or “elevation” of folk music to forms primarily associated with and consumed by the middle and upper classes.[38]

Regardless of the beliefs of individual Society members, their contributions to the Journal of the Folk-Song Society strengthened an ethnonationalist movement. In 1902, Vaughan Williams questioned why an English composer should attempt to found a style of music on “a class to which he does not belong, and which itself no longer exists,” referring to the peasants that were said by Herder to express the soul of the nation.[39] He later became one of the most prominent figures in the folk revival. Vaughan Williams also held the term “Merrie England” and its associated historical inaccuracies in contempt, yet he held a strong conviction importance of the cultural achievements of the folk and late Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean periods as a model for contemporary English artists, aesthetics which are also characteristic of Merrie England.[40] According to Graham Freeman, Vaughan Williams's suppression of his interest in the possibility of individual artistic expression in favour of “ironed-out” songs for the Journal cannot be seen as anything other than an ideological concession.[41] Similarly, according to Vaughan Williams, Lucy Broadwood “never, if she could help it, used the word "folk song,” and felt it a “betrayal of trust” to bring the songs “into the glaring light of the concert room and theatre, or to make them a cog in the educational wheel.”[42] Broadwood was an integral figure of the Folk-Song Society, being among its founding committee members and serving as its Editor and Honorary Secretary from 1904, remaining in her Editor position until 1926. Regardless, her misgivings about the consequences of the Society’s activities did not lead her to use her centrality within the Society to act on her moral concerns about the revival. While on its own, this could be attributed to Broadwood’s influence being limited by her position as a woman in a male-dominated organisation, in conjunction with Vaughan Williams' ideological conformity, it suggests that despite the apparent theoretical heterogeneity within the Folk-Song Society, individual grievances were suppressed.[43] The Journal remained united by a common nationalistic focus on folk song, intersecting with and independent of individual political affiliation.

The musical canon constructed by the Folk-Song Society lacked definable characteristics, making it vulnerable to redefinition and appropriation. Potentially as a result of the creation of the polemic relationship between folk songs and other popular music, in 1898 there emerged a perceived necessity “to distinguish what is genuine from what is emasculated.”[44] Revivalist logic had a tendency to discard the unknown and rely on perceived rational certainties to determine legitimacy, which were ultimately value judgements.[45] The conviction that folk music had a specific ethnonationalist origin led many collectors to edit and refine the songs they collected in an effort to cleanse them of “inauthentic” accretions, both lyrically and melodically. Censorship could also occur on the part of the performer.[46] Some singers practised self-censorship when performing for those they perceived as more refined than their usual audience, particularly if the collector was a member of the clergy or a woman, who both represented a significant proportion of collectors.[47] If an informant did deliver a song deemed unacceptable, the simplest solution for a publisher was to simply cut offending verses or entire songs.[48] Consequently, the canon of the folk revival was formed through a process of selection, exclusion and editing, the end product of which, if it could be linked to any form of identity, represented middle- and upper-class collectors rather than the people from whom they were collected.[49]

Prior to its construction by the Society, “Folk” music may never have existed, and that which was created should not be considered an essential expression. While it was understood as a lasting and “evolving” form of popular culture, many members of the Society failed to couple the continuity of folk music with the much despised popular songs favoured by their contemporary lower classes.[50] Folk music was detached from the melodies and depravity of the modern urban working class in order to preserve its sanctity in representing something other than the problematic modernity. However, in many country towns and villages, folk song had diminished in popularity.[51] It is precisely the decline of folk music that prompted many elites to fear the loss of a past way of life associated with English greatness and wholesomeness, but it also suggests that the accusations of appropriation from the working class commonly levelled against the Folk-Song Society are misguided. By propagating the understanding of folk song as essential to the character of a monolithic English working class, Marxist analyses such as that by David Harker perpetuate the nationalist and classist presumptions of the Society’s members rather than appreciating the dynamism and diversity of English geography. When folk music had been popular, it had not been catalogued and disseminated by state education but was about subjects which interested the singers and reflected their relevant socio-cultural context.[52] For the majority of rural England, this was no longer the case.

In conclusion, the Folk-Song Society contributed to the creation of a national musical identity in Britain through the selective and editorial translation of oral traditions throughout England to form an ethnonationalist identity that could be adopted by all British citizens. This identity was aesthetically centred on the southern English countryside and reinforced intertwined romanticised traditional values in response to the growing influence of foreign industry and culture, urbanisation, and racial understandings of the nation state. These findings represent but one chapter in the continuous negotiation of what it means to be English in a period when the members of the Society attempted to locate legitimate Englishness in a modernising world seemingly leaving Britain behind. As a result, they left a lasting impact on the study of folk music, the folk genre, and the aesthetic of the United Kingdom into the 21st century, while the music they deemed problematic remains in relative obscurity.

1 note

·

View note

Text

somewhere, in the middle of a forest, a baby bug was born...

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

10K notes

·

View notes