Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Blog Post 10

Virtual Reality: What are the limits?

In this day and age, we consumers are privileged to witness the advancement of technology. The people of our century have the opportunity to utilise many provided tools that previous generations never even considered to be possible, as well as the capabilities that come along with it. Devices, software and social media are consistently evolving. So, from now, how long would it take for media to become fully embraced by the real world?

In the fields of entertainment, likely not very long. Games have been on a rise of popularity since its focus in CGI, and signs show how they continue to thrive; their integration into real-life has been recently introduced to the mass audience through the wonders of Virtual Reality (VR).

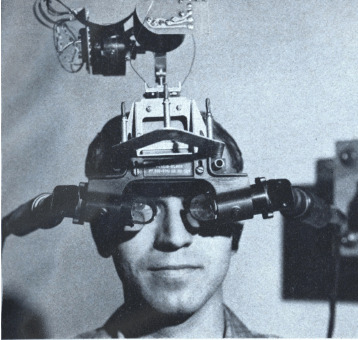

For this text, I would like to introduce the topic of virtual reality (VR) and explore the both the promises it could hold, as well as the precedent it could set for the future of gaming, let alone media consumption. VR was essentially a developmental concept "aptly termed by Jaron Lanier" during the 1980s, when the computer interface offered viewers a 'virtual world' that they could enter in (Heim, 1994, p. 17). However, the development of VR itself was derived from various products dating further back into the 20th century. Myron Krueger developed Videoplace (circa 1975) to assess artificial reality, as well as publishing a pioneering book titled after the term, Artificial Reality (1983). Earlier events featuring the development of VR stems from the inventions of both Ivan Sutherland and Bob Sproull's Sword of Damocles (1965-1968) and Morton Heilig's Sensorama (1955-1962). Regarded as the first VR head-mounted computer display invented, Sutherland is arguably the historical predecessor to today's VR helmets. (Rheingold, 1991, p. 58) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Despite this, the creations of VR has evolved and preceded overtime; it can been argued that the earliest traces of VR are set back into the nineteenth century, through attempts of 'real-life' illusions using panoramic paintings (Figure 2). Their purpose was to provide their viewers an entire field of vision, which has now evolved into 'point of view' (POV), a crucial asset in creating immersion within games.

Figure 2: Battle of Borodino (Roubaud, 1812)

More could be further explored if we were focused on exploring the concept and foundations of VR, as well as the theories behind it. However, I will prioritise the subject of VR as a tool and potential for gaming media in this submission. Regarding the various products of VR that were mentioned, they communicate a specific aim: to immerse viewers into a different world. In Rheingold's words, creating a "completely convincing illusion that one is immersed in a world that exists only inside a computer" (Rheingold, 1991, p. n1).

With this in mind, current games involving VR are exactly that; a compelling cyberspace allowing people to become immersed in. Immersion is a definite trait associated with VR, and is utilised heavily in VR games we can purchase today.

An example of immersion within VR is a popular community game VRChat (2014), an online platform where multiple users can interact with one another through VR. Users can integrate themselves within a fictional setting and customise their 3D avatars to express themselves (Figure 3). The idea of immersion within this product refers to the idea of escapism, by implementing yourself into a 'world' representing the opposite of real-life. Thus, this game holds many possibilities for creativity, such as skits, roleplays, and entertaining interactions with users from all around the internet. YouTube holds a massive category of videos exploring VRChat, as well as a consistent fanbase for it, despite many years since its release.

Figure 3

Thus, the prospect of VR could imply a future involving a more integrative approach to media. The possibilities that VRChat has brought to gaming encourages a precedent where products aside from this medium may be compatible with VR technology, and even sooner than we think; VRChat has already demonstrated a new capability of VR, through the socialisation of its community. This aligns with the predictions found within the foreword of Rheingold's book: that virtual reality will soon affect everyone's daily life - "in everything from communication to education, from business to sex" (Rheingold, 1991, p. n1). This example shown in later years from the book's release presents a credible point from Rheingold that this generation is indeed going through a technological revolution through VR, which could further progress and "take us into the next century - and beyond" (ibid, p. n1).

Despite this, with the new shift in technology, comes with new setbacks to resolve. It can be argued that the reason for the success of VRChat is because of its socialisation feature - had it not offered its users that, the virtual worlds inside its gameplay would not be as exciting or revolutionary. Thus, without any stimulants of interactivity, VR would merely resemble a husk of a game; an empty shell of a product.

This makes sense, given the origin of VR. It was not invented for entertainment, but rather for education. Rheingold states that part of VR technology was derived from flight simulators that the United States Air Force trained their pilots with (Rheingold, 1991, p. 16). Within these simulators, pilots learn about the basic mechanism of aircrafts "without leaving the ground, by practicing with a replica of airplane controls" (ibid, p. 16).

In relation to military use, Rheingold also claims The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) involvement within VR technology, regarding their contribution to VR models. NASA configured a system for VR technology by providing "high-tech" helmets to pair with "electronic-shutter glasses" during the 1980s (ibid, p. 17). In addition, NASA's provided system allowed the feasibility of affordable VR sets, thus peaking the mass' interest in pursuing research and development (R & D) into VR, resulting in the establishment of VR industries to be founded within the 1990s (Ibid. p. 133). Due to NASA's involvement, VR sets could be produced inexpensively, which Rheingold speculated this being behind the success of VR within the aforementioned simulators; "the Air Force had been flying million-dollar helmets for years" (Ibid. p. 133).

All of these variables further corresponds to the fact that VR technology was, while still in development, never intended for entertainment. This is further cemented by the fact that Ivan Sutherland, leading pioneer of VR, had a specific motive behind his invention. Originally, Sutherland envisioned VR to allow its users the experience to "create the mathematical model of the virtual world in the computer", enabling them to "look, feel, and sound as much as possible like a real world to the human mind that is coupled with it" (Ibid. p. 38). Therefore, the initial purpose behind VR was to integrate simulation with reality, not just simply representing it, hence the educational factors surrounding VR at the time.

That said, it could be argued that Sutherland's view would never have come to fruition, due to the threat of uncanny valley within such a simulation; Masahiro Mori theorises that if a representation of human likeness increases, the viewer's affinity decreases (Rhee, 2013, p. 303). Mori argues that concepts like prosthetic arms are a combination of human and non-human features, thus causing an eerie and cold sense of feeling in the viewer (MacDorman, and Chattopadhyay, 2016, pg 190). Recent scholar studies applying uncanny valley to three-dimensional (3D) film characters closely resembling humans found that their viewers "failed to identify with the characters, experiencing them instead as soulless or vacant" (Ibid. p. 190).

So, what does this mean for the VR technology and its future?

While the reasons behind the creation of VR may not have panned out the way its pioneers had imagined, that is not to say that the current expansion of VR and its promises of 'reality' is all for not. VR still has the potential to completely renovate how we consume media, though the process of its simulation will no longer be focused on capturing reality itself, but rather representations of it. Furthermore, this leaves a lot of concepts to experiment with in 'bringing to life'. Since nothing in VR is real anyway, why merely stick to realistic elements, when creators could produce a world for viewers to fully experience their fiction?

This is where the revolution of VR takes place; if its technology refrains from mimicking reality and instead embraces its fictionality, then the advantage of its immersion would perform best. Entirely fictional, even two-dimensional (2D) based works could be revolutionised through the use of VR; Rick and Morty: Virtual Rick-ality (2017) proves this statement. Despite the obvious cartoon style, the show's VR adaptation allows fans to experience a depiction of Rick and Morty (2013-2023) as if they are part of an episode (Figure 4). This corresponds to Rheingold's recollection of his experience with VR: "Cyberspace was everywhere I looked - above me, below me, behind me. I wasn't just watching it. I was in it" (Rheingold, 1991, p. 133).

Figure 4

In conclusion, while its conventions are still relatively new to the mass, VR has long been studied and finally figured out. The prospect it holds for media is profound, with the success of gaming experience being evident. The diversion in the initial perspective for VR has ended up giving this promising piece of technology a second chance, through further development within the entertainment industry (Ibid. p. 46). Overall, this generation can witness the breakthrough of technological experience, in which VR has the capability to provide.

Sources:

Adult Swim Games (2014) Rick and Morty: Virtual Rick-ality [Video game]. Available at: https://store.steampowered.com/app/469610/Rick_and_Morty_Virtual_Rickality/ (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

Franz Roubard (1812) Battle of Borodino [Painting]. Borodino Battle Museum Panorama, Moscow (Viewed: 27 December 2023).

Heim, M. (1994) The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacDorman, K.F. and Chattopadhyay, D. (2016) ‘Reducing consistency in human realism increases the uncanny valley effect; increasing category uncertainty does not’, Cognition, 146, p. 190.

Norman, J.M. (2024) HistoryofInformation.com. Available at: https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=861 (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

Norman, J.M. (2024) HistoryofInformation.com. Available at: https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=2785 (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

Norman, J.M. (2024) HistoryofInformation.com. Available at: https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=4699 (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

Rhee, J. (2013) ‘Beyond the Uncanny Valley: Masahiro Mori and Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’, Configurations (Baltimore, Md.), 21(3), pp. 301–329.

Rheingold, H. (1991) Virtual reality. Secker & Warburg.

'Videoplace' (2022) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Videoplace (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

Virtual Reality Society (2017) History of Virtual Reality. Available at: https://www.vrs.org.uk/virtual-reality/history.html (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

VRChat, Inc. (2014) VRChat [Video game]. Available at: https://hello.vrchat.com/ (Accessed: 27 December 2023).

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 09

Media and Affect in Game and Film

TW: Contains fictional imagery that may be disturbing for some readers.

Imagine being given a medium, with no prior knowledge of its source or narrative. You observe a scene and it unfolds like this:

A young fawn and his doe mother is seen fighting through a snowstorm. The food is scarce, with no other soul in sight. The baby deer struggles to eat off the barks of withered trees nearby, relying on his mother to reach them for him. Time passes; the wind subsides, leaving us a scenic imagery of the full moon surrounded in white.

Finally, we see a breakthrough in the environment: a batch of fresh green grass. The fawn, no longer worrying about starving, grows ecstatic and devours it with joy.

Though to his mother, something is wrong. As the viewer, you don't know what it is. You cannot see it. However, You can hear it. She quickly realises that they are not alone, and urges her son to run to the thickets with her immediately.

Gunshots radiate throughout the forest, as the scene intensifies. "Keep running!", cries the mother deer. Just as they both reach towards the embrace of the woods, one last harrowing gunshot is blasted. However, the fawn does not stop running - not until he reaches home. "We made it!", exclaims the fawn. The exhausted baby deer looms out of his hiding spot, confused. "Mother?"

He is met with nothing, but silence (Figure 1).

Figure 1

This disturbing scene is what establishes the narrative's tone shift in Disney's Bambi (1942), a film exploring the coming of age through the experience of a young deer. Throughout this film, Bambi learns about the loss and blooming of the relationships in his life. Even without its synopsis, the film successfully communicates the dangers in life, allowing viewers the relatability of losing a loved one through Bambi's story. From the orchestrated diegetic, to the bleak ending confirming Bambi's loss. Every single element within this scene ties into an overall message of grief - a feeling we can all experience.

Queue in the philosophical explanation behind our experience with media. Originally, the concept of affect theory was still relatively an independent field of studies during the 1990s. This process of figuring out the correlation between media and affect is till on-going to this day. In finding out the impact of affect within today's media, let us first establish the foundations of affect as a concept.

Cultural theorist Clare Hemmings (2006) studied the subject of affect within cultural theory surrounding the foundations of constructivism and psychoanalysis within, which she delves into the sociocultural research of gender theorist Federica Giardini (1999). In her papers, Giardini states that affects are defined as "necessary states of pain and pleasure", further clarifying its establishment within both Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis: being the "qualitative expression of our drives' energy and variations" (Giardini, 1999, p. 150). Hemmings further elaborated on Giardini's claim, stating how affects and emotions are separate, by pointing out that affect "broadly refers to states of being, rather than to their manifestation or interpretation as emotions" (Hemmings, 2006, p. 551). Furthermore, Hemming explains the impact on affect within the grounds of cultural theory, stating that affects are "what enable drives to be satisfied and what tie us to the world" (Ibid. p. 551).

Hemming also claims that as well as being an object distinguished from emotions, the idea of affect is capable of transferability, which she compares and states that "unlike drives, affects can be transferred to a range of objects in order to be satisfied, which makes them adaptable in a way that drives are not" (Ibid. p. 551). Thus, affects can enable the satisfaction of a drive or interrupt it; this is useful in explaining context of where the drive for hunger is satisfied with good food versus interrupted with bad food (Ibid. p. 551). In its basic form, affect is when a source creates an emotional charge in its atmosphere, so much so that it spreads out and contaminates the subjects around. In short, is it a type of force or intensively, unbound to any distinct feeling and emotion.

One way a medium does to reel in its audience is to present their product in a way that captivates their feelings. In the instance of Bambi, aside from diegetic sounds, the film also utilises visual traits of affect. The traditional animation within the film is depicted as raw and genuine, supported by Disney's renowned style. This is evident through the variety of depictions involving Bambi's struggle throughout the winter season, as well as his grief and distress over losing his mother. This can be further elaborated through Creative Technology associate professor Sophie Mobbs (2015), an animation enthusiast who produced a paper focusing on affect in animation. Mobbs explains that animators "learn a set of postures and expressions, piecing together an emotional scene with an alphabet of symbols, almost as if spelling out a word" (Mobbs, 2015, p. 80).

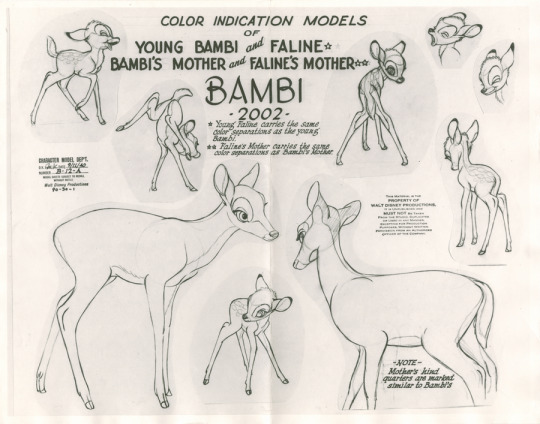

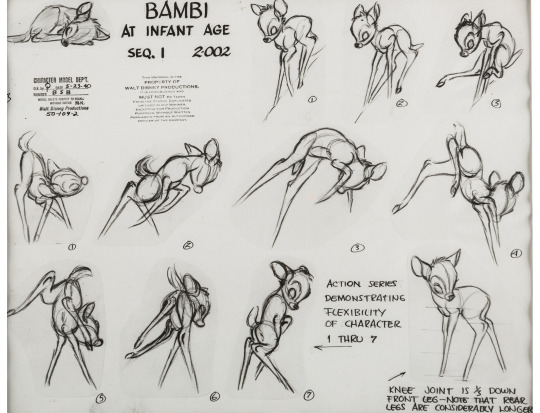

As employees within a company, model sheets are likely used as guide for animators who worked on the production of Bambi. This is a standard protocol within the animation workforce, of which all departments in a team must co-operate with each other's workflow. This is to help present a seamless flow within a product, thus maintaining consistency throughout the entirety of its film. Animators refers to this as being 'on model' (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

The fluid, impactful motions carefully crafted within the movements of Bambi throughout the film helps convey to viewers each expression he makes, thus providing a sense of emotion exuded from his character. In short, the ability of animators to convey emotions through their works enables the ability to evoke emotions from their spectators - equivalent to understanding emotions portrayed by actors within films.

However, while a medium may set out clear visual implications of how we should react to certain cues of affect, they are merely implications at best. This means that, without the context of narrative, the meaning behind visual performances will risk being misinterpreted; Mobbs states that when tasked with portraying expression in animation, animators still face the difficulty of their audience only possessing the ability to perceive emotion through "the filter of the animator" (Ibid, p. 80).

This makes more sense when provided Stuart Hall's theory of encoding and decoding of affordances, which Adrienne Shaw critically engages with the pitfalls of failed communication in the coding circuit (Figure 4).

Figure 4

According to Shaw, Hall's explanation to failed interpretations of a distribution associates with how the encoding and decoding stages "may not be perfectly symmetrical", due to the likelihood of misunderstandings or 'distortions' arise from "lack of equivalence between the two sides in the communication exchange" (Hall, cited in Shaw, 2017, pg. 596). This explanation from Hall was cited in the cultural theory papers of Simon During (1993), which further explored the dilemma regarding the encoding and decoding model; while each stage of encoding and decoding are equally 'autonomous' from one another, the coding of a message does manipulate its reception, as each stage have their own determining limits and possibilities (During, 1993, p. 90).

When referring back to the scene of tragedy in Bambi, as much as animated expressions go, the depiction of deer feeling despair over the loss found in a predictable situation such as hunting is as far of a tear-jerker as it goes. Therefore, in regards to its affect on its audience, the interpretations would vary from inconvenience to wildlife at worst, and pensiveness in losing a parental figure at best.

So, while the objective in causing affect through media may not overall pan in favour of its intent, this could be dependent on the type of medium - after all, Stuart Hall's theory was only an analysis on products such as television. With that, what if we delve into a more interactive medium?

A type of media where the prior limitations explored are not present is gaming. Gaming, a medium known for complete interactivity with debate on its inclusion of narrative, could be able to demonstrate affect that does not require the necessity to establish narrative conventions; this approach pertains to the affect of horror games and their audience's experiences.

Figure 5

While affect surfacing certain emotions such as happiness and sadness may be challenging, the scope of horror games is, especially if of good-quality, the easiness of conveying horror itself to evoke fear from audience. Many people are scared of horror, especially since they cannot be sure of what to expect - this is the strong suit of games in its ability to convey such affect.

No Players Online (2019) features a seemingly abandoned map, paired with the eerie ambience of diegetic sound effect. Its players are left with no context of the deserted server, other than a 'score 0/3' objective and the ability to explore around. As the experience progresses, players are encouraged to resolve this predicament by collecting all three flags scattered throughout. However, this aim is a fallacy, in order to blindside gamers with a build-up of horror, such as jump scares by a disfigured stranger and amped-up dread from misplaced elements intentionally spawned (Figure 5 and 6).

Figure 6

Even towards the ending of the game, a narrative was never established; all that was left was the mystery of a lore merely hinted, but never revealed. Despite the puzzle of its plot, the experience of No Players Online was made clear that players were meant to be scared of whatever lurked in there. Therefore, the connection between affect and to a game like No Players Online proves to be successful in what it intended to evoke, which is fear in anyone that plays it.

The simplicity of horror and effect is a genuine evocation, due to it being an expression everyone is familiar with, and so we are not immune to the surprise of horror games, or the idea of horror itself. This can be further elaborated through the affect-cognitive theory, a model which explains how our behavioural strategy in decision-making is based on our experiences, emotions and irrationality. Using findings by psychologist Daniel Kahneman (2003), strategy researcher Matteo Cristofaro created an affective-cognitive theory in relation to how individuals vary in reaction towards decision-making, which he explained how cognitive functioning within the human mind is made of two "systems" (Cristofaro, 2020, p. 346).

He states that the first system is where "intuitive and unconscious thinking lays", while the second system is reserved for more reflective thoughts, in which prompts individuals to recognise mistakes that occurred within reasoning (Ibid. p. 346). From his investigation, Kahneman observed how cognitive operators of "System 1" are "fast and automatic", due to being driven by prior experience and emotions, thus making them "difficult to control or modify" (Kahneman, 2003, cited in Cristofaro, 2020, p. 346). In contrast, operators of "System 2" are "more likely to be consciously monitored and deliberately controlled", which the psychologist describes as the filtering output for System 1 (Ibid. p. 346). While the theory concerns the action of decision-making, reactions to horror games may still apply regarding our cognitive functions processing fear; our first round of gameplay will produce an involuntary reaction, compared to our second, of which by then we will know what to expect.

Another psychologist, Robert Zajonc (1980), further clarified that judgements are "evoked by an affective evaluation happening even before any higher level reasoning occurs", which papers from other researchers (Finucane et al., 2000) found that for decision makers to efficiently assess risks and benefits of certain situations, their emotions will "substitute logical reasoning" through rapid judgements (Cristofaro, 2020, p. 346).

Sources:

Bambi (1942) Directed by D. Hand. [Feature film]. California: RKO Pictures.

Cristofaro, M. (2020) “I feel and think, therefore I am”: An Affect-Cognitive Theory of management decisions’, European management journal, 38 (2), pp. 344–355.

During, S. (1993) The cultural studies reader. Routledge.

Hemmings, C. (2005) ‘INVOKING AFFECT: Cultural theory and the ontological turn’, Cultural studies (London, England), 19 (5), pp. 548–567.

Mobbs, S. (2015) The Evocation and Expression of Emotion through Documentary Animation. Animation Practice, Process & Production: Intellect.

Pype. A., D'Heer. W. (2019) No Players Online [Video game]. Available at: https://papercookies.itch.io/no-players-online (Accessed: 31 December 2023).

Shaw, A. (2017) ‘Encoding and decoding affordances: Stuart Hall and interactive media technologies’, Media, culture & society, 39 (4), pp. 592–602.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 08

Semiotics and Politics: Battle for Representations

For a narrative to unravel, a hero must tend to an objective. We experience his journey across his world, as we share his interactions and aspirations. We bond with him by immersing ourselves into his every action and reaction to his environment. We, as the spectators, manage to 'become' him, by seeing through his lenses.

However, we cannot read his mind. We don't have any leads for this, either; we would have to interpret his actions for ourselves. This leads to the question of: what encourages his actions and story as a character?

To prove against the odds and make a name out of himself, we discover what the purpose behind his actions are. Folklorist Vladimir Propp observes this through his extensive knowledge on Russian narratives; function 'XXVII' details the hero's aim in becoming a changed man, recognised for his courage from a "mark, brand, or by a thing given to him", proof of his accomplishment through adversity (Propp, 1968, p. 62). Thus, function 'XXXI' grants the hero his wish, and pays him handsomely - either money, a kingdom or a princess' hand (Ibid. p. 63-64).

Through Propp's papers, we may understand his 'motive'. However, what could be the hero's 'motivations' behind his character?

Queue the character function of the princess, arguably the least represented archetype in narrative history. In recent discussions of narratology within media, much criticism of representations have been brought to light, particularly within the film industry. The most notable theory to come out in recent century involving glimpse into feminism is Laura Mulvey's (1975) analysis of the 'Male Gaze' in her essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975).

Since her breakthrough, many film and feminists theorists acknowledged the idea of consciousness within perceiving certain representations in film, and has now become a current means to identify and improve representations in media as a whole. This blogpost will feature a condensed timeline of theories revolving around representations of gender and race, including psychoanalytic relations to the correlation between film and its audience.

Firstly, introducing the arguments of film bias by Laura Mulvey (2016), who both analyse the power relations of real life connected to film. Mulvey focuses on the how the identity of consumers of popular culture text influence and relay their interpretations (Understanding Gender & Sexuality in Popular Culture, 2016, p. 8). Moreover, I will also examine the progression of current media representations following the analyses of Mulvey's work.

To start my exemplar timeline involving gender, I will refer to the older works of Disney and how the shift within their princess line-up may be correlated to the reception of feminist theory. Novelist Bridget Whelan (2012) explored Disney's representation of women overtime and noticed how the depictions of their first princess characters correspond to the novel standards of women in the 20th century. Citing Deborah J. O'Keefe's book titled Good Girl Messages (2000), Whelan explains that novels written for girls coinciding with the 'first wave' Disney princess films suggested a popular viewpoint where, in O'Keefe's words, girl heroines must possess a "sweet voice so low it could hardly be heard"; "misty, lisping and inaudible, and even better for her to be dead" (2000, cited in Whelan, 2012, p. 23-24).

This is evident in the narratives of Disney films Snow White (1937), Cinderella (1950) and Sleeping Beauty (1959). 'Leading' characters within these films all suffer from a fate of 'death-like comas', who then require to be rescued by their suitors (Whelan, 2012, p.24). Snow White is poisoned and falls into an eternal slumber, much like Aurora from Sleeping Beauty, who suffers from a curse and is also put into slumber. (figure 1 and 2) While Cinderella may not have suffered a physically ill fate, she was nonetheless "rescued from a socially inactive state - a state of poverty and servitude", to which she was conditioned to possess a voice that fell on deaf ears (Ibid. p. 24) (figure 3).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Thus, this evidence from Disney persuades a notion with underlying messages about the standards of women's place in society, by conveying their concept of "princesshood" akin to 'contemporary' standards of ideal girlhood (Ibid. p. 23-24). However, why must the first princesses of Disney relay such standards? What was the interest in silencing female characters, in their own stories no less? Are they not the heroines themselves?

Mulvey (2016) proposes the reasoning for this practice within film, titled the male gaze. She claims that within a patriarchal culture, the woman stands as 'signifier' for the man to live out his "phantasies and obsessions"; a stage is set up in posing a silent image of the woman "tied to her place as bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning" (Mulvey, 2016, p.26). In short, the only purpose of a woman in the world of patriarchal entertainment is to merely contribute her appeal, and nothing more. Mulvey cultivated this theory after extensive analyses featuring the inner-workings of the male's psychosexual development.

Famous for his founding of psychoanalysis, neurologist Sigmund Freud analysed and developed a psychological term called 'scopophilia'. In Mulvey's papers, she delves into Freud's findings of scopophilia by explaining how he "isolated scopophilia as one of the component instincts of sexuality, which exist as drives independently of the erotogenic zones" (Ibid. p. 28). Thus, scopophilia came to represent a habit in "taking other people as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze", hence the strong resonance to Mulvey's implications in her theory (Ibid. p. 28). With scopophilia applied, Mulvey communicates that such gaze of a spectator is only possible within a world "ordered by sexual imbalance", which divides males and females into 'active' and 'passive' roles; "the determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female figure which is styled accordingly" (Ibid. p. 30). This analysis in behaviour likely explains the predicament in which women are placed in regarding film, as the media form is used as a means to project deep-rooted desirable imagery of certain representations to society; Female representation is a subjection to be objectified.

Although this particular presentation seems formulaic, Sarah Rothschild (2013) offers an explanation as to why depiction of women are often sexual: Women were generally overlooked and therefore underrepresented, previously "undefined" within fairy tales (Rothschild, 2013, p. 2). Rothschild points out that throughout literature and film media, the princess' character has "long been a model for emulation and explication", thus embodying 'extreme femininity' that stems from "socially desirable behaviour" (Ibid. p. 1-2). Furthermore, Rothschild states that the princess character instils these desirable behaviours upon the "girls and women in the culture that produces her" (Ibid. p. 1-2).

With this, we can assume that the sexualised depiction of women within past films partly resembles historical trend of femininity, and consequently part of psychological desires involving women. Rothschild strengthens Mulvey's statement regarding how many princess stories have reflected cultural expectations, roles and responsibilities from girls and women in the time periods they were released in (Ibid. p. 2). Rothschild further added that with Disney's aforementioned first three princess releases, the studio had adapted animation into the film industry by valorising feminine representation with romance (Ibid. p. 2). However, what has this entailed in its future animations?

Overtime, representations of gender have become more engaged with in the field of politics, business, and sports, with media now following suit. The debate on having accurate representations of minorities within entertainment has grown stronger in voicing criticisms directed at societal perceptions that are now deemed obsolete. Disney and its massive competitors have slowly come to terms with this and have eventually redirected their princess narrative, through their most recent additions to their princess line-up: Brave (2012), Frozen (2013), and Moana (2016) all contain its latest princess characters possessing traits that contrast to its first three princesses - showing their own skills, aspirations and ambitions (Figure 4, 5 and 6). Rothschild points out this progression of representation by identifying how these products "offer heroines who combine their independence and achievement with only a secondary interest in romance" (Ibid. p. 2-3).

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Sources:

Brave (2012) Directed by B. Chapman. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Cinderella (1950) Directed by C. Geronimi. [Feature film]. New York City, NY: RKO Pictures.

Frozen (2013) Directed by J. Lee. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Mayher, J. (2016) Understanding Gender & Sexuality In Popular Culture. Indiana University Bloomington: Cognella.

Moana (2016) Directed by R. Clements. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Propp, V., Scott, L. and Wagner, L.A. (1968) Morphology of the Folktale. 2nd edn. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Rothschild, S. (2013) The Princess Story: Modeling the Feminine in Twentieth-Century American Fiction and Film. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc.

Sleeping Beauty (1959) Directed by W. Reitherman. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) Directed by D. Hand. [Feature film]. New York City, NY: RKO Pictures.

Whelan, B. (2012) ‘Power to the Princess: Disney and the Creation of the 20th Century Princess Narrative’, Interdisciplinary humanities, 29 (1), p. 21.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 07

Realism and Media: What is really there?

In the idea of conventions, we must understand what brings spectators to the depiction of reality. To conceive an idea and illustrate it within a medium is, while seemingly a baseless decision, an enigma that attracts many to consume its product.

In the grand scheme of things, many people yearn for an understanding of our world; the conceptualisation of realism and what we could conceive of it is endless. Countless debates amongst philosophers on the truth behind 'realism' has allowed further growth of understanding in how we perceive the reality around us.

This blogpost will cover particular conventions of realism covered from the paradigm structure in analysing realism, as well as philosophical arguments into what defines reality.

First off, let us establish the definition of realism. In the language of philosophy, realism refers to claims of an object that are true, being 'independent' from others and their bias; this is termed as "mind-independent objectivity". (Cole, 2023) Thus, objects that are depicted as 'real' can exist regardless of anyone's belief, especially if such object contains a level of 'truth' (Ibid. 2023).

This argument of realism branches into a discussion between two variations of philosophy, termed ontology and epistemology; one theorises on how an entity exists, whereas the other sets out to prove if such an entity exists or not (Blakeley, 2023).

In relation to realism, the main concern of its concept refers to what makes an entity or object 'real' to an individual. Professor of English David R. Shumway argues that realism involves a 'set of conventions', in a sense that an object of realism does not necessarily prove how its representation of the world is accurate, but rather to provide an insight into how it could represent it (Shumway, 2017, p. 183). This aligns with the claims by literary critic and historian Ian Watt in regards to perceiving realism; "formal realism is, of course, like the rules of evidence, only a convention" (1957, cited in Shumway, 2017, p. 183).

That said, the scope of 'formal realism' that Watt implied is, while a challenging convention, may still have some merit to be valid based on human experience. This means that while a concept of realism within a medium is merely limited to being a concept, its 'realistic' foundations may be transparent enough to possess some truth to it. Shumway further elaborates on this sentiment, by explaining that realism harbours a relationship "with what holds to be true; it attempts to tell the truth about certain elements of the world, but it may or may not exceed in that attempt" (Shumway, 2017, p. 183). In short, an object depicting realism could pertain to any product within a medium, which depending on its nature, is capable of representing some semblance of truth of the world.

Such object of realism will be investigated through a selection of media, which will be analysed into what can be depicted as 'realism', and how there could be an array of methods in portraying realism. Within these texts, I will elaborate on a few representations of the paradigm of realism; the two distinct types of focus will be hypermediacy and immediacy. Starting with hypermediacy, we can analyse this type of realism within media through the evolution of Disney's franchise The Lion King.

Figure 1

With the first release under its franchise, The Lion King (1994) received high praise over its advanced use of animation technology at the time, as well as its strong narrative being filled with many memorable characters (Figure 1). Arguably the most influential film Disney has ever produced, The Lion King went on to having multiple sequels and spin-offs; from cartoon shows to features within Disney's Animal Kingdom theme park in Walt Disney World Resort.

However, the once 2D based famous film has begun to see a shift into realistic representations after its instalment of live-action elements, such as its London musical adaptation debuting in 1997 and, most recently, the 3D re-animation of The Lion King (2019) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Throughout the book of identifying realism within media, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin (2000) critically engaged with the idea of remediation, which consists of two strategies; Hypermediacy is one of such strategies. In their definition, hypermediacy is "a style of visual representation whose goal is to remind the viewer of the medium" (Bolter, and Grusin, 2000, p. 272).

Contrary to Disney's depiction of The Lion King (2019) labelled as a 'live-action' film, it has received nominations for the Best Animated Feature Film awards, though director Jon Favreau explains the medium predicament involving The Lion King. Favreau claims that the recent film is "neither live action nor animated", as he explains that since there was no live animals or cameras present in the film and instead it had all been "through the hands of artists" (Lee, 2022). However, Favreau argues that his film should no longer be viewed as a 'remake' of the original, since the term 'animated' would be misleading; the 3D film is not stylised the same way as its cartoon counterpart it, which Favreau utilised his previous experience to produce a film akin to the feeling of watching "a BBC documentary" (Ibid. 2022). Through The Lion King, Favreau won the Satellite Award for Best Animated or Mixed Media Feature (Wikipedia, 2024).

This could explain the tendency to alternate between both dynamic and realistic expressions within The Lion King; the film has the ability to demonstrate both of worlds, through its hyper realistic rendering and expressions of fantasy during its songs. The hybrid of medium falls into hypermediacy in a sense that while viewing the film, spectators would remain sceptical of what the product would identify with, since it seems like a thin line between reality and fiction. In consequence, this likely awareness could lead to lack of affinity in being able to indulge in such a medium. It could possibly fall into a sub-territory of uncanny valley; while Masahiro Mori's theory concerns the eerie representations of human likeness correlating to viewer's affinity, it can be argued that due to The Lion King's subject being animals, it would not affect viewers as much as realistic human characters (Rhee, 2013, pg 303). Nonetheless, the juxtaposition between an expected portrayal of life in the Sahara versus an uncharacteristic Broadway-style musical akin to circus animals performing stunts seems surreal. These stark depictions would break any realism, as well as the 'hyper realism' of The Lion King, rather quickly. I will present a comparison between a 'heightened' scene of both a BBC documentary (Planet Earth II, 2016) and The Lion King (Figure 3 and 4).

Figure 3

Figure 4

There is potential to depict realism successfully using hypermediacy, though that is unlikely without taking into account the second strategy of remediation, which is immediacy. According to Bolter and Grusin, immediacy involves the desire to go above its own medium in placing spectators into the "objects of representation themselves" (Bolter, and Grusin, 2000, p. 83). Both theorist explain how immediacy has become more prominent as our technology expands - paintings, photography, film, television, and most recently, virtual reality (VR); all of these media forms offer spectators at least a "promise of immediacy" (Bolter, and Grusin, 2000, p. 60). With this, Bolter and Grusin explain that the method behind remediation mainly "favours immediacy and transparency", though with time, new opportunities for hypermediacy will emerge as media continues to evolve (Ibid. p. 60).

Sources:

Bolter, J.D. and Grusin, R.A. (2000) Remediation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Cole, D. (2023) Study.com. Available at: https://study.com/academy/lesson/realism-overview-practical-teaching-examples.html (Accessed: 6 January 2024).

Lee, T. (2022) Academy of Animated Art. Available at: https://academyofanimatedart.com/is-the-lion-king-movie-live-action-or-animated-jon-favreau-says-neither/ (Accessed: 6 January 2024).

Planet Earth II (2016) BBC One Television, 6 November, 20:00.

Shumway, D.R. (2017) ‘What Is Realism?’, StoryWorlds, 9 (1-2), pp. 183–195.

The Lion King (1994) Directed by R. Allers [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures.

The Lion King (2019) Directed by J. Favreau [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

'The Lion King (2019 film)' (2024) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lion_King_(2019_film) (Accessed: 6 January 2024).

Trigg, R. (1980) Reality at risk: a defence of realism in philosophy and the sciences. Brighton: Harvester Press.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post - 06

Transmedia and Synergy: The Never-Ending Plot

When we are asked about the most iconic fictional characters, most people would probably answer with Superman, Batman, or of the sorts; whatever notable character there is from a well-known series. It may not be specific to comics, but characters from any popular title can also be examples. Media products deemed as 'famous' overtime will urge in new consumers, even if their origins are dated from way back.

People become familiarised with notable stories and grow up alongside consuming similar plots of which are eventually popularised, with the potential to be reintroduced or elaborated upon further to a new audience for more exposure, be it sequel or prequel. Thus, a community of fans will be formed, sharing common interests, theories and ideal execution of their favourite stories. This in turn leads to a continuation of a product, now regarded 'famous' enough to be considered iconic within media.

In the practice of Media, this process is referred to as commercial intertextuality, which is "the production and interlinking" of main texts such as blockbuster films or TV series, with para-texts of other mediums like spin-offs, promos, online media, books, games, and merchandise." (Hardy, 2015, p. 327) When one generation gets to experience a phenomenal product, another reinvigorates it after in order to keep it relevant within the media. Thus, this method of popularising products leads to an accumulation of branch narratives, which could extend to other possibilities, thus making a product not just any product, but a cultural phenomenon.

While examining the theory of intertextuality, I will be referring to the famous franchise of Spider-Man. With his first debut in Marvel's comic, Amazing Fantasy #15 (1962), the character Spider-Man had become a big hit and has since grown to be a famous feature within Marvel's universe. Over many decades, the creation of this character has spawned many products across various media; films, games, television series and merchandise had arise as the story of Peter Parker grew overtime. To this day, many theories and reviews revolving around Spider-Man are produced and shared by his massive fanbase on social media, as well as memes and fanfictions revolving around his narrative still remain relevant for comedy and relatability, further reinforcing the mass' affinity of Spider-Man and his world. (Figure 1)

Figure 1

In what makes a product of intertextuality, professor Sara Gwenllian-Jones (2003) wrote about the qualification of its properties by describing its overall function to be 'centripetal', in a way that its references branch out many possible meanings towards a single text (Gwenllian-Jones, 2003, p.186), which explains the extension of references like memes and parodies from online in relation to Spider-Man scenes or concepts. Gwenllian-Jones also referred to media scholar John Fiske's (1987) analyses of intertextuality, which he explains that intertextual knowledges "pre-orient the reader to exploit polysemy by activating the text in certain ways, that is, by making some meanings rather than others."" (Fiske, 1987, cited in Gwenllian-Jones, 2003, p.186). The key word being 'reorient' describes the relationship between small products and the bigger narrative; what loopholes are there in its plot? What else could be uncovered from the story provided to us viewers who might want more from a sequel? Maybe a prequel? Or perhaps something more alternative?

Products that are popularised to the point of continuing plots deemed as unnecessary could branch outwards, in order to explore more of the universe of its concept rather than its character, which leads to the idea of transmedia. So, in theory, what is transmedia?

Through the works of media scholar Henry Jenkins (2011), transmedia refers to a by-product of "a radically intertextual story" played out across different media; with each new text further adds to the clarity of a story "as a whole" (Wall, 2019, p.2) In other words, following the impact of an original media, this content 'moves' into future textural structures within a similar medium. This can explain existence of remakes, sequels and prequels based on the original source. However, this does not inherently make a product a transmedia. Rather, it is also the dependence on multimodality that results in transmedia, being that the content's 'movement' would involve having separate representations distinguished from the original plot.

One profound example we can take of transmedia is Sony Pictures' Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018), which explores a new reality of character Miles Morales following the death of the initial Spiderman, Peter Parker. The plot within this film series is separate to the narrative explored within the comic series, of which both of Miles face different relationships and fates. However, the unravelling plot within the film's sequel ties in both of these products, by revealing that a dimension paradox is what caused Miles to become Spiderman. At the beginning of the film, the spider that bit Miles Morales (Earth-1610) originated from a different dimension (Earth-42). This point is clarified through a cliff-hanger ending, where a brand new character is introduced. This character was none other than Miles Morales, but from a Spiderman-less reality, had instead adopted the alias Prowler (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

This expansion on Miles' story arc had been highly appraised by long-term critics and reviewers of the Marvel's products, as well as became a hit in the Box Office regarding its recent release in theatres, grossing $690.5 million at the worldwide box office (Wikipedia, 2023). The reason could likely be that this narrative addition to Miles' story adds further sophistication to the Spiderman timeline, of which the original comics failed to represent in the past.

In the context of comics alone, Miles' narrative was initially a minor concept that delved into an alternative reality of Spiderman's fate. Marvel's Ultimate Comics was essentially a product to explore 'reimagined' versions of their different characters, leading to Miles' very first appearance in Ultimate Fallout (2011) #4 (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Furthermore, this representation of Spiderman could be what has led to an open interpretation for Miles' purpose in the entirety of Spiderman's arc, thus leading to potential plots yet to be discovered. The film adaptation was brought with this notion in investigating what Miles could truly contribute to the Spiderman franchise.

While the extensive exploration into Spider-Man alone could last someone a while of catching up to date with the current theories revolving around the story, such a feat in media could never be possible without the prospect of capitalism. How is the success of Marvel's work possible in the world of capitalism, and what business does it have in the lives of its consumers? In Gender, Race and Class in Media: A Critical Reader (2015), Jonathan Hardy elaborates on the current media fanbase's obsession with brands like Marvel. He describes the formation of supporters in the setting that nurtures it as "consumer culture", where we fixate on an environment that is "saturated with advertising imagery urging us to buy and consume products as a path to future happiness and self-transformation" (Hardy, 2015, p. 241). As result, fans buy a product and indulge in it until they grow bored and request for a new an improved piece. The entertainment industry takes advantage of this and formulate a means to produce further profit off successful releases. However, is it so bad when people genuinely enjoy the products they purchase?

In conclusion, we are a generation that has the capability to take products we admire and further develop them to create something new. Within this time of media, we can look back many works over the last few decades and pick out aspects that could reinvigorate them, or maybe even invent the next best thing in media, as creators of our own 'consumer culture'. For as long as the entertainment industry manages the distributions that feed the cost of productions, do we get to savour the memories of our favourite stories and characters once more.

Sources:

Brooker, W. and Jermyn, D. (2003) The audience studies reader. London: Routledge.

Dines, G. and Humez, J.M. (2015) Gender, race, and class in media: a critical reader. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Reddit (2022) Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/memes/comments/ytmjse/spiderman/ (Accessed: 7 January 2024).

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023) Directed by J. Dos Santos [Feature film]. Culver City, LA: Sony Pictures Releasing.

'Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse' (2024) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spider-Man:_Across_the_Spider-Verse (Accessed: 7 January 2024).

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018) Directed by J. Dos Santos [Feature film]. Culver City, LA: Sony Pictures Releasing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post - 05

Heroes, Villains, and the Reformation of Narrative.

In the general scope of narrative, we always have had clarity of what outcomes to expect. Through the perspective of our hero, we expect a transformation into someone stronger than what they once were. We look to see their goals accomplished, and their happy ending rewarded. In some narratives, we may also look forward to a schadenfreude outcome, reserved for villains that we eagerly await the downfalls of. These are common tropes of which we have grown up with and usually expect from the conventions of narrative, as it brings us overall satisfaction; Bordwell and Thompson (2016) points out how all these principles "allow a story to arouse and fulfil our expectations" (Bordwell, Thompson and Smith, 2016, p. 49).

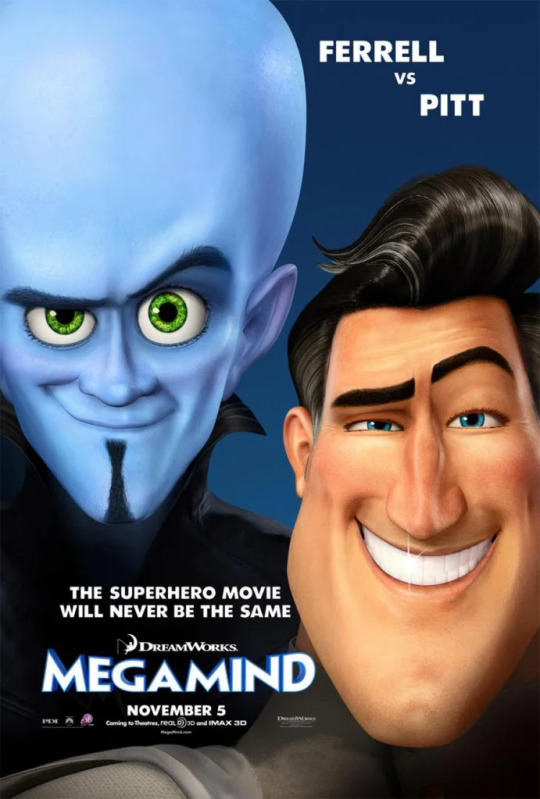

In contrast to my previous essay blogpost, here I will be showing modern examples of a more refreshing approach to the oppositions between hero and villain, using studio Dreamworks' products as my examples to argue with Propp's functions; Shrek (2001) and Megamind (2010). Minor exploration into other sources will also be included. In this blog post, I plan to uncover the story dynamic between heroic and villainous traits in film, and why in some instances they are not as opposite as they are depicted to be.

Point 1: A hideous monster - as a hero?

In countless fairy tales, readers perceive a hero as a visible representation of might and inner good; a strong and handsome man. They stand out in their battles against their foes, obstacles portrayed as monstrous beasts. The standards set within tradition allows a model for viewers to look up to. Out of all the characters in the fictional, it is the hero who we resonate the most with. Additionally, everything that transpires within the story is through his lenses, which enables viewers to connect with him further - to inspire, comfort and guide us.

Much of media has continued to practice this within the 21st century - films, TV shows, and even games. One example of a series, Samurai Jack (2001-2017), maintained the strong opposition of portrayal between hero Jack and villain Aku. Despite the extensive worldbuilding of Samurai Jack overtime, the basis of enmity between Jack and Aku has remained stark; white and black, good against evil, man versus monster, and so on (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Highlighted by folklorist Vladimir Propp (1984), ethnologist Claude Lévi - Strauss developed a theory of structuralism within narrative, which he referred to as 'binary oppositions'. Lévi - Strauss claims how binary functions are complimentary within narrative and should be "reduced to one", Propp argues that such functions are likely split "between different people" - being the hero and the villain (Propp et al., 1984, p. 75). Propp explains this by stating examples of binary tasks, such as how one character 'imposes' a difficult task, while the other resolves it (Ibid. p. 75). While it can be argued that Lévi - Strauss' binary analysis could sum up the entirety of a narrative as a structure of itself, Propp was concerned that such assumption would be misleading, due to the apparent fact that binary actions among characters have mainly been separate (Ibid. p. 75).

Nonetheless, Propp acknowledged Lévi - Strauss' examination in discovering the deterministic traits within narrative consisting a "network of pluses and minuses". (Ibid. p. xli) This is a likely explanation as to why Aku and Jack's clashing relationship offered a balanced plot. Overall, the structure of narrative that is dependent on the dynamics between hero and villain seems to cement the impression from viewers of a formula that should be followed accordingly.

However, binary oppositions had freeform within its rules, which has led to unique outcomes regarding narrative. In 2001, animation studio DreamWorks released a family-friendly comedy film titled Shrek, the first of its soon established franchise. The story features not a predictably handsome man as its protagonist, but an ogre hiding deep within the woods (figure 1). Shrek, a name derived of German noun Schreck for 'terror', is the name for our unlikely hero of this series. His name holds true, as he is considered a terror among the people of his universe; the villagers are petrified of him and the Kingdom of his land want him dead.

Figure 1

The reception of Shrek during the time of its release was unexpected. For a concept revolving around a monster hero fighting against an evil king and rescuing the princess who, also represents a monster, was likely an intriguing tale to see pan out in the 2000s. Like all major releases, Shrek implements pre-established cinematic codes to its plot; Professor Emerita Pam Cook (1985) refers to Noel Burch's (1973) popular model of Institutional Mode of Representation (IMR), which she elaborates its significance in identifying "conventions of mise-en-scene" within film, by means of how a narrative's "space and time" are set up and how its characters "individuated in ways which both engage, and are imperceptible to, the spectator" (Cook, 1985, p. 39). However, the establishment of IMR in film is likely due to to the correspondence to 'cultural ascendancy' within narratology, of which was already determined by formulaic codes examined from folklore history (Ibid. p. 39).

So, how come a "big, stupid, ugly ogre" (Shrek, 2001) is supposedly the assigned hero of the film's narrative? Film critics were quickly able to decipher this and find out how there is more to Shrek and it's unexpected plot. Currently, Shrek is considered a highly rated film on popular review site 'Rotten Tomatoes', with a rating of 88% on its 'tomatometer'. (rottentomatoes, n.d.). The overall critics consensus for this film is as follows: "while simultaneously embracing and subverting fairy tales, the irreverent Shrek also manages to tweak Disney's nose, provide a moral message to children, and offer viewers a funny, fast-paced ride." (Ibid. n.d.) It was obvious of the purpose behind the plot of Shrek entailed, which most film critics gave it high appraise for its bold storytelling outside the usual traditions of narrative. Thus, Shrek is recognised to be one of the few films that went against the grains of normalcy within narrative conventions.

Moreover, another film of DreamWorks that is argued to be one of its best releases is the second instalment of the Shrek franchise, Shrek 2 (2004), which further delves into the aspects of narrative archetypes within traditional fairy tale. In this sequel, Shrek and his companions discover potions manufactured by the story's main antagonist, the Fairy Godmother. They steal a particular potion possessing the ability to transform characters into a reversed identity of themselves. From it, Shrek obtains an easily swayable image of a handsome man, while his friend Donkey turns into a full on stallion (figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2

Figure 3

This element, labelled as the 'Happily Ever After' potion, relates to the powers of a typical fairy godmother when transforming characters into positively reinforced images within folklore. However, it is always temporary. This leads to an overarching reflection within the film's plot; despite the supposed role of a hero, Shrek is not recognised as one, as he is rejected by his princess lovers' parents, as well as feared by the majority in his universe; Much like the first film, he is treated like a villain rather than a hero. Furthermore, Shrek 2 makes a crucial point in changing the stereotypes of archetypes and challenging aspects that are held to their titles - Shrek is not the only character to break out of narrative stereotypes. The deuteragonist, Princess Fiona, is not a typical princess, due to her nightly curse of becoming an ogre (Figure 4 and 5). The film's Fairy Godmother is the false hero and revealed main antagonist of the film, posing as an obstacle to Shrek becoming recognised as a hero and stopping his aspiration of marrying Fiona (Figure 6).

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Despite the change of portrayal within films such as Shrek, it can be argued that the only aspect that has been altered in narrative is the appeal of their characters, as the structure is essentially the same as any other fairy tale. Regardless of the alignment of characters within a narrative, Propp highlighted that functions will always represent "an act of a character", in relation to their significance in progressing into the next course of action; "functions of characters serve as a stable, constant elements in a tale, independent of how and by whom they are fulfilled" (Propp et al., 1968, p. 21). Furthermore, DreamWorks had later produced another filmic release that would closely interact with the theories Propp had provided in his papers, and challenge them (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Megamind (2010) features an initial villain supposedly successful in 'killing' the hero of his universe, presenting an alternative structure of the 'lack' that would have been presented as cueing in the hero of the story, not following their defeat. In fact, Propp's narrative functions imply that the hero 'must' always prevail, and that the villain's defeat is certain; "XVIII. The villain is defeated" (Ibid. p. 53) In this film, supervillain Megamind feels unmotivated living life after having defeated his enemy Metro Man, and to reinvigorate the dynamic in Metro City once more, Megamind attempted to create a new hero who ended up becoming a villain. This push in the film's narrative forces Megamind to adapt to a new role, which eventually reveals that he is the 'true' hero of the story.

This story of Megamind was capable in addressing the rigid methods of storytelling found within Propp's investigation, primarily the fact of Propp's functions cementing a "predictable, formulaic way of storytelling" (1975, cited in Propp, 1984, p. 38). The experimentation found within Megamind not only concerns the dynamic between archetypes, but also how narrative functions could be portrayed different than the usual formula of storytelling derived from folk tale.

Both Shrek and Megamind make a point in specifying how narrative events are not formed by implications of archetype presentations, but rather explicit actions caused by characters of any type. There is only so much functions can do in explaining certain texts, though that does not mean the material can be predicted. Propp makes this claim stating that while similar functions may lead to "rise of similar manifestations", it does not inherently influence material, which he describes is "not dead matter" (Propp et al., 1984, p. 69) Thus, the success of functions in predicting the materials' direction is merely "only a possibility" (Ibid. p. 69).

Sources:

Bordwell, D., Thompson, K. and Smith, J. (2016) Film art: an introduction. Eleventh; McGraw-Hill international; Place of publication not identified: McGraw-Hill Education.

Cook, P. and Bernink, M. (1999) The cinema book. 2nd edn. London: British Film Institute.

Megamind (2010) Directed by T. McGrath. [Feature film]. Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures.

Propp, V., Martin, A.Y., Martin, R.P. and Corporation, E. (1984) Theory and History of Folklore. N - New; 1; Edited by A. Liberman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Propp, V., Scott, L. and Wagner, L.A. (1968) Morphology of the Folktale. 2nd edn. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Samurai Jack (2001) Cartoon Network, 10 August, 23:00.

Shrek (2001) Directed by A. Adamson. [Feature film]. Universal City, CA: DreamWorks Pictures.

Shrek 2 (2004) Directed by A. Adamson. [Feature film]. Universal City, CA: DreamWorks Pictures.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post - 04

Hero and Villain: Making the most of Narrative Tropes

If one could simplify the complexity of narrative, how would they go about it? Many media products of today shows a renowned formula for this question. Throughout the long-term existence of narrative, the specific formula we all recognise from countless texts goes something along like this:

Firstly, a setting is established, which addresses the 'lack' that creates a stake of the story. This is usually caused by the villain, who's character is revealed much deeper into the plot. This 'lack' often concerns the absence of a princess or family member involved with a hero, in which the story sets the stage for, who then receives the plot's task in venturing and resolving its dilemma.

This traditional narrative structure was analysed by analyst Vladimir Propp (1968), who theorised the 31 functions of Dramatis Personae, as well as the 8 archetypes in narrative; two of which are arguably the most important types, being the hero and the villain. Once again, the concept of narrative will be reintroduced for context. Narrative is a unique concept that humans can perform, by delving into a setting of which anyone could place themselves in and relate to. This comes natural to humans, as we have an innate yearning for knowledge. Bordwell and Thompson describes humans as harbouring an "endless appetites for stories" (pg 72), thus suggesting that a significant factor within successful narrative forms involves our curiosity. (pg 55)

Which begs the question: how and what does narrative provide, in which peaks our curiosity to begin with?

On one hand, the idea of the 'stakes' raised within the plot may entice our interest. While reading a story, we wonder about the difficult situation placed within the narrative, and may come up with a scenario of how it could resolve itself. The 'stakes' may concern a threat to the life of a character, usually being the 'princess' of the narrative, or a threat to the story's setting, of which will cease to exist if not resolved promptly. However, would it be the raised 'stakes' that lures in the audience to the story, or the characters that cause such stakes themselves? It could be argued that the characters are the main interest of stories. Thus, I will delve into the analysis of the hero and the villain.

First, starting with the heroic personage of a story. They are identified as a 'protagonist', who is considered the main character in a story. They are the pivotal characters of a narrative, thus having the entire plot revolving around them; the story will be affected based on their actions and decisions. (Wikipedia) The objective of a heroic character is to solve the interdiction of the story, which they are often given the task to 'seek' out the issue caused by something unbeknownst to the audience. That, or they coincidentally 'seek' this opportunity themselves whilst they are already on an adventure; Propp explains this through function "X" (Propp, 1968, p. 38).

In Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), the setting is established when we watch the protagonist, Peter Quill, get abducted out in an open field from Earth at a young age. This is followed up with the current plot taking place by the time Peter has already adapted to a new lifestyle in space and becomes a notorious galactic rogue we now know as Star-Lord. (Figure 1) Thus, we have a sense of who he is in the current state of the narrative, as he coincidentally 'seeks' the plot's objective whilst mid-journey throughout the galaxy, further determining the story's direction to revolve around him. This order of narrative aligns with Propp's 'X' function of how a plot begins with the hero receiving his objective whilst already on an adventure in the world.

Figure 1

Aside from a prioritised perspective, narrative may also give the audience more reason to connect with the hero, usually involving the hero's likability or likeness of character. Peter Quill already portrays attributes that we as the audience can relate to. He stands out as an average human in the film's vast line-up of alien characters. The beginning scenes of the movie already provide us the opportunity to connect with Peter Quill, as we witness his human emotions and tragic backstory that we can relate to; we watch him grieving the loss of his mother from cancer during his childhood. (Figure 2) This exploration shows how akin to us Peter is, therefore we would be naturally inclined to support him in the story.

Figure 2

Through Propp's work, we can identify a reason behind the popularity of narratives. Propp recognised the significance that heroes play in their tales, as well as the impact they make on the viewers. According to Propp's findings, the most important feature within Russian epic poetry is the "heroic character of its content, based on their 'deeds' within the narrative, thus encouraging viewers to prioritise studying the inner content of heroism within epic poetry". (Propp, 1968, p. 149) This perhaps explains our interest in seeing narratives to the end and why many modern films rely on the protagonist of their stories.

Whilst examining Russian folklores, Propp established the function of the villain, who has the need to "disturb the peace of a happy family", thus causing some sort of misfortune, damage or harm in the process (Propp, 1968, p. 27). Their main purpose in the story is to prevent the hero from completing their task, thus withholding the resolution to the plot. One could argue that the villain is the main personage of the narrative as opposed to the hero, due to their actions being what sets the the "actual movement of the folktale" (Alan Dundes, 2007, p. 156). While the audience would support the heroic character for their acts of good deeds, this would not prevent the villain's character from receiving any spotlight; Enrique Cámara Areanas (2011) argues that stories are likely to be successful when there is a compelling villain featured. (Areanas, 2011, cited in McLaughlin et al., 2022, p. 68)

Ronan the Accuser is the main antagonist of Guardians of the Galaxy (Figure 3). A war-driven, power-hungry maniac who rules the Kree Empire, he is notorious across the galaxy for his radical nature. As Peter Quill associates with more characters within the film, he realises how nefarious Ronan is once he hears about the negative interactions his new friends had with him; fellow comrade Drax had his family taken from him by Ronan, which the Accuser showed no remorse for.

Figure 3

Comfortable with taking lives of others in the name of his empire, Ronan's character easily provides suspense in the film whenever he appears or is mentioned, creating further engagement with the product (Arenas, 2011, cited in McLaughlin et al., p. 68). Thus, the threat of this character is prominent throughout the story, serving as a 'narrative catalyst' up until the end (Ibid. p. 68). Peter and his team almost lost their lives while fighting against him; had Peter not had the friends he made alongside him, he would have likely died from Ronan (Figure 4). This type of predicament offers a buzz within a product that lures people in to spectate, thus the possibility of a negative ending causes further engagement with the story (Bezdek, and Gerrig, cited in McLaughlin et al., 2022, p. 68).

Figure 4

To conclude, both archetypes offer much sophistication in the events of a story. Without villains, there would be no need for a hero, as they provide the drama that the plot depends on (Arenas, 2011, cited in McLaughlin et al., p. 68). In turn, without heroes, there would be no story, as we learn through the hero's actions and experience their wisdom and knowledge. Both are essential in creating a story to teach the younger generations of how to live life.

Sources:

Bordwell, D., Thompson, K. and Smith, J. (2016) Film art: an introduction. Eleventh; McGraw-Hill international; Place of publication not identified: McGraw-Hill Education.

Bronner, S.J. (ed.) (2007) ‘On Game Morphology: A Study of the Structure of Non-Verbal Folklore’, in. Utah State University Press (Meaning of Folklore), p. 154.

Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) Directed by J. Gunn. [Feature film]. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

McLaughlin, B., Dunn, J.A., Velez, J.A. and Hunter, J. (2023) ‘There must be a villain: political threats, narrative thought, and political violence’, Communication quarterly, 71 (1), pp. 64–85.

Propp, V., Martin, A.Y., Martin, R.P. and Corporation, E. (1984) Theory and History of Folklore. N - New; 1; Edited by A. Liberman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Propp, V., Scott, L. and Wagner, L.A. (1968) Morphology of the Folktale. 2nd edn. Austin: University of Texas Press.

0 notes

Text

Blog Post - 03

The Impact of Narrative on Game

Narrative has proven to successfully integrate within text, and it has continued to adapt to modern products of this century, such as novels, films, animations and games. It still cultivates the way we digest information in our lives and provides a slate for how we should interact with the world. Theorists have attempted to explain the phenomenon of narratives, though does it work with interactive products, such as gaming? That is what I would like the delve into. I will be exploring the history of games, video games and how the evolution of narrative has extended into this medium.

Before analysing the connection between games and narrative, I researched the origins of games. Games had been around before the A.D. period (Figure 1). The Royal Game of Ur is regarded as the "oldest playable board game in the world", originating back 4,600 years ago during the Mesopotamia period (British museum, 2021). Board games are still a popular form of entertainment and are the epitome of interactivity, requiring engagement with other players; the idea of competing against something in order to win has been the main objective of gaming. Notable examples of this are Monopoly and Chess.

Figure 1

Regarding 'video games', Bertie the Brain (1950) is the first of its kind to exist. Initially, the audience was not so inclined to compete with an artificial intelligence in a game of Tic, Tac, Toe. However, the stance of playing video games shifted after the successful launch of Atari's Pong (1972), which allowed the interactivity of two human players using a digital format (Figure 2). The game received mass revenue and can be argued to have "started the video games industry" as a whole, setting out to become "the first commercially successful game" by selling 150,000 units of its home edition (Pong Game, n.d.).

Figure 2

Many well-renowned titles were born from the development of video games; Pacman (1980), Donkey Kong (1981), Street Fighter (1987) and so on. Companies like Nintendo and Capcom grew to fame from the success of the steadily growing video game market. However, when did a shift occur where video games decided to adopt narrative into their interactive experience?

To understand the eventual trend of narrative games, I will once again explain the term narrative and the significance it holds within media and our language. Film theorists Bordwell and Thompson (2016) describe narrative as "a fundamental way that humans make sense of the world" (Bordwell and Thompson, 2016, p. 72). It offers experience of situations and reason as for why events unfold the way they do. Most narratives contain a dynamic proposition through their plot that lures spectators in to investigate and interpret for their own, which both Bordwell and Thompson describe as our curiosity (Ibid. p. 55) Games must also evoke a level of curiosity in motivating the audience to play them, which then implies that some form of dynamic activity must be at play - something that narrative forms are popular for (Ibid. p. 73)

As narrative further evolves in our timeframe, so does media and technology around us. With new prospects of narrative conventions, comes with new forms of execution. The potential of video games have never been bigger, as we now have easy access to online platforms, multiplayer servers, freeform simulations and multi-choice experience. A particular type of game that has come from narrative conventions is interactive games involving different outcomes of stories. One example is Until Dawn (2015), an interactive horror video game where players can control the survival outcomes for 8 characters. Until Dawn provides countless choices for each individual, as well as countless endings of them living and dying; the key scene within the game is the last, where depending on the players' choice for their characters, the endings can range from all characters surviving to all but one of them dying. (Figure 3 and 4)

Figure 3

Figure 4

This presentation of narrative within a game like Until Dawn displays the use of parallelism structure, which is known for diverging a main plot into sub-branches to present different characters rather than only focusing on one. Bordwell and Thompson states that within film, this allows a story to become more 'complex' than the traditional presentation of a plot (Ibid. p. 74). In the case of Until Dawn, this can also describe the structure of interactive games. Moreover, each sub-branch of focusing on different characters within this game also implies secondary plots that all coincide with the primary plot. These 'subplots' revolve around each of the characters' interactions and relationships with one another, followed by how each of them react in situations unfolding in the main plot. With this, players can acknowledge and grow an affinity with certain characters that they like in the story, thus each variant in choice or ending will likely have a different effect on players, compared to if the game only featured a main plot (Ibid. p. 75).