Text

I think it’s so interesting how this film embraces its unique position in cinema, acknowledging both the frustration and significance of being labeled the "first of its kind." Cheryl's journey as a filmmaker mirrors her own life, digging into history to uncover the buried narratives of Black queer individuals like Fae Richards. It's fascinating how the film challenges the notions of representation and identity, blurring the lines between reality and imagination. The parallel between Cheryl's relationship with Diana and the historical relationship between Fae and Martha is compelling. It delves into the complexities of interracial queer relationships and sheds light on how white lesbianism often approaches Blackness with a voyeuristic curiosity. This exploration of race within queerness opens up discussions on the challenges of representation and power dynamics within relationships. The film's ending, where the audience's reflection is left staring back, feels like such a significant moment. How does this reflection encapsulate the film's message about the viewer's participation in shaping meaning within cinematic representations, and what does it suggest about the audience's role in reimagining narratives?

The Watermelon Woman: Queer representational strategies as possibility

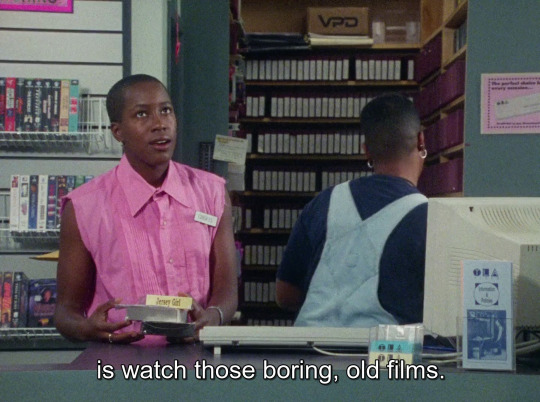

Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) made history as the first feature film written and directed by a Black lesbian–but the film knows this and extensively explores its appellation as the “first of its kind,” a title Dunye simultaneously treats with frustration and reverence. It’s strikingly self-aware, funny, and inventive, a semi-autobiographical story about Cheryl, a video store clerk and chronically single filmmaker who decides to make a documentary on a mysterious Black actress from the 1930s pigeonholed into playing “mammy” roles who appears in the credits of a film called Plantation Memories simply as “The Watermelon Woman.” It’s a movie about movies! “I am a Black lesbian filmmaker who's just beginning,” Cheryl says, and here the thesis of the movie exhumes itself. The text demonstrates a preoccupation with the power of identity as a representational strategy through imagery and insists on its existence, the Black lesbian gaze resisting hiddenness behind the camera and crafting a visible narrative powered by the excavation of archival memory, the straddling of truth and representations of truth, of real and imagined. Dunye’s filmmaking mirrors her own life while the fictionalized version of herself seeks her own image in the black-and-white static of footage nearly lost to history. The Watermelon Woman chronicles the myriad of interconnected dynamics between art and real life–its awareness of the ways it is speaking about and to itself is demonstratively pointed, with Cheryl often speaking directly to the camera about her project and desire to tell Fae’s story.

Fae Richards, the eponymous Watermelon Woman, symbolizes the Black queer archive that future generations of Black queer filmmakers like Cheryl strive to hold within their canon, and as Cheryl interviews subjects for her documentary on Fae and digs through archives she finds proof not only of Fae’s existence but of her queerness¹. She discovers that Martha Page, the white director of Plantation Memories, and Fae were in a relationship, all the while navigating her own dating life, getting entangled with a white video store patron named Diana, much to her best friend Tamara’s dismay. The ways Cheryl’s relationship with Diana parallels Fae and Martha’s excavates the possibilities and challenges of “race relations” within queerness and the ways white lesbianism often possesses an objectifying curiosity with Blackness. The film’s theoretical standpoint as a piece of media that presents a representational theory of Black queerness pointing out gaping holes in the so-called canon is made imminent by some of its casting choices–cultural critic and infamous haver of weird opinions Camille Paglia appears as a parody of herself and a mouthpiece for white feminist film theory offering a misguided take on the “mammy” sterotype, and love interest Diana is played by Guinevere Turner, cowriter and star of the 1994 lesbian film Go Fish. The Watermelon Woman theorizes that sexuality and race are mutually constitutive and through the production and reception of representational imagery this interrelation is complicated by the relationship between the creator and the recipient of an image–Cheryl is a lover of film as much as she is a filmmaker and a large portion of her desire to tell stories about the complexity of being a Black woman who is many things at once comes from her desire to consume these stories.

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” bifurcates queer imagery into “positive” and “negative,” necessarily locating “butch” as a visual identity located in media representations in one of two pathologies². Butchness in film is often leveraged to be emblematic of non-normative female sexuality in a way that is easily visually understood, and as a result, butch lesbians in film have more often than not functioned to be objects rather than subjects of inquiry. Halberstam posits that the debate around positive and negative images often returns to early feminist film criticism calling for “positive representations,” categorically rejecting depictions that could be received in their full complexity as anything other than “good.” Halberstam complicates the idea of a positive image by postulating that this desire for queer imagery imbedded with messaging that campaigns for itself places “the onus of queering cinema squarely on the production rather than the reception of images.” The Watermelon Woman explores how cinema is queered both through the production and reception of images; Cheryl watches Plantation Memories for the first time, she reads the queerness in it and it becomes a queer text because of her viewing, then when it is revealed that The Watermelon Woman and the film’s white director were in a relationship, her read is validated. Cheryl’s onscreen presence as a butch lesbian is overtly queer and her and Tamara’s open discussion of lesbianism as well as an intimate sex scene between Cheryl and Diana underscore this film’s goal of moving beyond the implicit in representation, further informing the lesbian lens with with Cheryl uses to analyze and interpret films like Plantation Memories.

Plantation Memories is not a real film, but it might as well be as it represents the startling politics of race films of its time where the white Scarlet O’Hara-type starlet weeps in the arms of the nurturing Black woman with such vigor that it’s hard not to believe in its existence. The consequence of the effects films like it produced continue to be felt in strategies of representation and Fae Richards does not represent an easily “positive” image of queerness–instead occupying a space in the troubling tradition of the racialized dominant images of Black women in film–yet Cheryl recognizes herself in Fae’s performance partially because it is so fraught. She identifies in her relationship with Diana a similar dynamic to Fae Richards and Martha Page, who only cast her lover in highly stereotyped and racially singular roles, where her lesbianism and Blackness are at slight odds with one another when in a relationship with a white lesbian who can relate to her based on only one of those central tenets and displays a voyeuristic and ultimately isolating interest in the other one. The Watermelon Woman argues for complexity beyond “positive” and “negative” imagery and constructs a Foucauldian reverse discourse where negative imagery can be positively productive when viewed critically and rethought. The film invests in the prospect that art can be a two-way conversation and that by beholding representational images, we project our possibilities onto it. The image on the screen dims and the reflection of the audience is left peering back at itself--Dunye holds onto this moment and treats it with tenderness, imbuing this empty space with hope.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Ratnarajah, Anoushka. “Indisputably Real: Cheryl Dunye’s the Watermelon Woman.” Out On Screen, August 6, 2021. https://outonscreen.com/blog/2020/news/indisputably-real-cheryl-dunyes-the-watermelon-woman/.

Halberstam, Jack. Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film" In Female Masculinity, 175-230. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822378112-008

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

hooks and Kaplan's perspectives on the oppositional gaze and the gendered differences in the Black experience offer valuable insights into the portrayal and perception of Black women in media, particularly in the context of representations that have historically been filtered through biased lenses. Your analysis of "Bad Hair" aptly demonstrates how the film grapples with the complexities of Black womanhood, albeit with problematic depictions. The emphasis on hair as a central theme in the film becomes a symbolic battleground, reflecting societal standards of beauty and success. The portrayal of pain associated with natural hair treatments and the reinforcement of straight hair as the epitome of beauty echoes the perpetuated standards ingrained by societal norms. The tension between characters like Anna and Zora, exacerbated by their differing hair choices and skin tones, not only signifies colorism but also points to the systemic oppression perpetuated within institutions. Your analysis brings forth the film's shortcomings in authentically representing the Black female experience, yet it also provides a platform within a genre typically devoid of such representations. It enables Black female spectatorship, allowing critical examination and oppositional gazing despite the film's problematic narrative.

Critical Film Analysis: Bad Hair (2020)

In Bell Hooks’, “Black Looks: Race and Representation”, she defines what she has coined as the oppositional gaze, which is in contrast to the hegemonic gaze of white dominated societies. In the ability to gaze, also comes with it the ability to cast perceptions, which, as seen countless times as a result of the white gaze, has led to the formation of racial stereotypes. Hooks also highlights the power of looking, and how it can be seen as “confrontational, as gestures of resistance, challenges of authority”(Hooks 307). Looking proves to be particularly important for those who have been made subservient to the white gaze for centuries. Hooks hones in on the oppositional gaze in the context of Black women, and their use of it as resistance against the prejudiced ways that they are represented. Historically, the lack of accurate representation has led them to be accustomed to being falsely perceived through the gaze of others. Often times in media, Black women are fed representations of themselves that reflect racist ideologies, affecting the way that they view themselves. Because Hollywood and other major media outlets are dominated by white executives, depictions of Black women are blatantly filtered through their biased lens. Lack of representation can contribute to feelings of powerlessness, and impact the social, emotional, and physical relations of Black women. Hooks also acknowledges the Black gaze, which differs between men and women. In E. Anne Kaplan’s, “The Film Theory Reader: Debates and Arguments”, she states that “This gendered relation to looking made the experience of the Black male spectator radically different from that of the Black female spectator” (Kaplan 309-10). Given the different experiences had by Black men and Black women, they’re not able to have the same perception of themselves, each other, and the world around them. In Justin Simien’s 2020 film, Bad Hair, we see this disconnect represented on screen. The film attempts to act as a satirical commentary on texturism, but simultaneously villanizes Black women for their stylistic hair choices in the process. The villainization of Black women is commonly seen through the gaze of Black men, who have internalized the hatred towards Black women derived from white supremacy. The film, however, does call upon Black female spectatorship, which implores a sense of power that is historically stripped from Black women. Bad Hair also serves as a horror/comedy, giving Black women on screen representations in genres where they usually are not seen to exist, giving variety to Black womanhood.

Bad Hair (2020), set in 1989, follows Anna Bludso, a young Black woman. Anna works for Culture, a television station that features Black musical artists. She wants desperately to move up in her company, in which her adviser and boss, has been replaced by Zora, the antagonist of the film. Upon Edna’s, her original boss, departure, the audience is made to note several key differences between her and Zora. The most pertinent one being their hair; Edna has long, natural locs, while Zora has a jet-black, silky weave. From the beginning of the film, there is much emphasis placed on hair. The film opens with the establishment that natural hair is other, and in need of control, as we see Anna attempting to relax her hair as a child. Anna is displayed with a chemical relaxant sitting in her hair, and when she groans due to the pain from it, her sister responds with “It just means it’s working” (Simien 00:31). This insinuates that pain is inherently a part of the Black female experience, as is natural hair. After beginning to rinse the product out, we see that her hair had a terrible reaction to it, resulting in a permanent scar in the back of her head. Though this event can be relatable to many Black women, the scene is meant to evoke a sense of discomfort around natural hair, as we see her burnt scalp paired with a sizzling sound. Through this portrayal, it seems as if Black hair is untameable, and the act of having to deal with it is worth pity from the audience. This scene represents Black women’s hair through the Black male gaze, as a Black man might focus on the pain associated with natural hair, whereas Black women seeking accurate representation would see their hair as a source of beauty and power. As the film progresses, it reaffirms that straight hair is the standard of beauty, and indicates that it also grants economic success, as we see the people in positions of power possessing long, straight hair. Numerous times we see Zora urging Anna to no longer wear her hair natural, as it does not fit the new look that the television station is going for. Though she finally does it, their difference in hair choices acts as a source of tension, and an indication of their differing status. Zora is also a very fair skinned Black woman, whereas Anna is of a darker complexion, and while their contempt for each other is meant to symbolize the effects of colorism within institutions, it pins two hard working Black women against each other. These women are seen taking out their aggression on each other, when it is the systems of oppression created by white people that are really to blame. The Black male gaze sees Black women as aggressors in every situation, even when they are the victims. This narrative is pushed when we learn that the weaves worn by Black women in the film, including Zora and Anna’s, are blood-craving murderers who control the women wearing them. This objectification of Black women as perpetuators of violence even when violence is done unto them, clearly shows a lack of Black female perspective in the creation of this film.

In mainstream cinema, women “do not function as signifiers for a signified (real woman) as sociological critics have assumed, but signifier and signified have been elided into a sign that represents something in the male unconscious” (Kaplan 210). In this movie specifically, the Black male unconscious is reflected in the horror that is supposed to be Black women’s hair.

Though the problems with the film are evident, it places the Black female body in a genre where it’s usually not represented. It allows for Black female spectatorship, and in that, the ability to critique, and look in opposition.

Works Cited:

Hooks, Bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Routledge, 2015.

Furstenau, Marc. The Film Theory Reader: Debates and Arguments. Routledge, 2010.

Simien, Justin. Bad Hair, 2020

“White Gaze” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 March 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_gaze

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This analysis really digs into how Middle of Nowhere challenges stereotypes and centers the narrative on Ruby's journey, her struggle between loyalty and self-discovery. It's fascinating how the film doesn't offer a clear resolution but rather emphasizes Ruby's agency in crafting her own path. The exploration of the oppositional gaze is particularly intriguing here, highlighting how the film subverts mainstream narratives and offers a fresh perspective on Black women's experiences without relying on stereotypes. Ruby's internal conflict and uncertainty about her future are relatable elements, making her journey feel more authentic. The open-ended conclusion leaves room for interpretation, echoing the complexity of life's choices. Considering the subjective lens used to tell Ruby's story, do you think this approach adds depth to her character or might it limit the audience's understanding of the broader themes in the film?

Critical Film Analysis: Middle of Nowhere(2012)

Ava DuVernay’s second film, Middle of Nowhere, follows Ruby, who puts her life on hold as her husband Derek is incarcerated. She is seemingly friendless, living alone in a dimly lit apartment with occasional visits from her mother, sister, and nephew. She has single-mindedly dedicated herself to her husband for four years of his eight year sentence, while unintentionally abandoning herself. She gives up her dreams of going to medical school, and works the most unpleasant shifts as a nurse to balance seeing him. When Derek is up for parole at the midway point of his sentence, Ruby learns of his infidelity and the violent encounter that caused his parole to be denied. She realizes then that she has to navigate the fine line between loyalty and self sacrifice, wondering at what point maintaining her marriage might just be foolish. When her bus driver, Brian, begins to show interest in her, she is further swayed towards creating a new life for herself.

The film explores the past, present, and future identities of Ruby through the critical theoretical approach of gender and sexuality. All of the film’s main characters are Black, with a Black woman being the protagonist. Perhaps as a result of being directed by a Black woman, the film overtly challenges stereotypical depictions of Black women. In her essay, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators”, bell hooks argues that the oppositional gaze is a critical framework through which Black women resist the dominant, often negative, images of themselves perpetuated by mainstream media.The essay emphasizes the importance of Black female spectators actively interpreting and critiquing media representations, highlighting how the oppositional gaze could be used to reclaim agency and subvert stereotypes– the act of looking itself can become a site of resistance. hooks writes, “We do more than resist. We create alternative texts that are not solely reactions. As critical spectators, black women participate in a broad range of looking relations, contest, resist, revision, interrogate, and invent on multiple levels”. Middle of Nowhere creates a story centering a Black woman’s life through the oppositional gaze. It is not a reaction to other bodies of work, rather an independent look into the life of an individual Black woman without relying on stereotypes or preexisting narratives to further the story. Although Derek is the driving force behind the plot, the audience knows little of his background or the reason he is in prison. The film isn’t about him; rather, it shows how his sentence infiltrates every aspect of Ruby’s present and future as a catalyst for her growth and change.

The film not only focuses on romantic relationships, but also delves into familial connections. Ruby’s mother, Ruth, is particularly distressed by her daughter’s choices, believing that Ruby is holding onto a failing marriage at the expense of her future. During a family dinner with Ruby, her sister, nephew, and Ruth, Ruth yells at Ruby to speak up for herself, repeating the phrase, “just say something”. The film emphasizes the impact of incarceration on the partners and relatives of prisoners, illustrating how they too can feel imprisoned. Ruby intensifies this sentiment by dismissing any suggestion that Derek might face a prolonged sentence as a result of his own actions, and that he may not be advocating for himself effectively. She adamantly rejects any indication from her sister, mother, and even herself that suggest that she might need something beyond waiting indefinitely for Derek, even if it involves abandoning other paths forward or opportunities for fuller self-realization.

The film has no definite ending, but does display Ruby’s transformation from a passive character to an active participant in her life. In her essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Laura Mulvey introduces the idea of the "male gaze," suggesting that both the camera and the narrative reinforce a voyeuristic and fetishistic perspective that objectifies female characters. Mulvey examines how women are often positioned as passive objects of desire, reinforcing traditional gender roles. She writes that “The image of woman as (passive) raw material for the (active) gaze of man takes the argument a step further into the structure of representation”. Ruby is not portrayed as a sexualized object of desire by the camera or in the context of her relationships; her agency is the very thing that drives the narrative. DuVernay takes what could be a more classic love triangle and turns it into an exploration of Ruby’s inner turmoil. Neither men are actually important to the film. Ruby’s beginning as a devoted housewife is her doing what she believes is “right”. However when she begins to see Brian, her view of right and wrong is fundamentally changed. The film neither condones nor condemns Ruby’s infidelity, instead using it merely as another avenue for Ruby to explore other paths forward. The film ends intentionally ambiguous; Ruby does not choose Derek, Brian, or her career. There is no “right” choice, only a different one.

Some critics argue that the film perpetuates stereotypes by depicting an African American woman whose life is defined by her husband's incarceration. It is essential to recognize that the film intentionally chooses to explore the impact of the criminal justice system on families, particularly within communities of color. Incarceration disproportionately affects Black and Brown communities, and by honing in on Ruby's experience, the film sheds light on the prison industrial complex without stereotyping. It can also be argued that because the film is told entirely through Ruby’s perspective, often through montages and flashbacks of her life, it isn’t a reliable way to perceive the events of the story or extract anything meaningful from it. However, this subjective lens adds more emotional depth to the story, and allows the viewers to have a more intimate view into Ruby’s internal conflict. There is no definitive solution or right answer to her path forward; instead, the film underscores Ruby’s proactive decision to instigate change in her life.

At first glance it may feel as though Ruby is caught between choosing her husband or Brian. However, throughout the film, she is instead caught between the expectations of all of those around and discovering what it is she wants for her life. Derek expects her to be by his side and wait, Brian expects for her to accept his interest and create something new, and her family expects her to go after her career and start all over. Through Ruby’s final monologue, it’s clear that she doesn’t know what she wants and is content in that uncertainty. She says, “We are long lost, we are long awaited. The past has disappeared, and the future doesn’t exist until we get there”. She is going to figure it out, and that journey is just as important as if she already knew her destination.

¹ hooks, bell. "Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators." In Black Looks: Race and Representation, 317. Boston: South End Press, 1992.

² Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." In Movies and Methods: An Anthology, edited by Bill Nichols, 721. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Film Analysis: Love & Basketball

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xmTgozILMEuBzjrQlRwJGVPjhmLKjrX_/view?usp=drivesdk

Love and Basketball chronicles the intertwined lives of Monica and Quincy across four distinctive periods. Their childhood friendship rooted in basketball becomes complicated when Quincy accidentally injures Monica, leading to a rollercoaster of emotions but ultimately forging a deep connection. As teenagers, they navigate high school life, with Quincy's popularity and Monica's basketball prowess setting the stage for a budding romance that endures despite challenges. Their college years bring individual struggles: Quincy grapples with media scrutiny and family issues while Monica contends with coach conflicts, straining their relationship to a breaking point. Fast forward to their professional basketball careers, Monica playing overseas and Quincy in the NBA. A pivotal moment arises when Quincy faces an injury and impending marriage, prompting Monica to confront her past and chart a new course. Their love ultimately triumphs, sealed by a high-stakes basketball game, leading to marriage, parenthood, and Monica's eventual achievement in the WNBA, symbolizing their enduring connection through their daughter's love for the game in the post-credits scene.

Monica's character in Love and Basketball serves as a powerful canvas for examining Judith Butler's concept of gender performativity. Her journey and passion for basketball intricately challenge and redefine traditional gender roles, offering a profound exploration of performative gender within the film. Butler argues that “hegemonic heterosexuality is itself a constant and repeated effort to imitate its own idealizations” (338), meaning that our prescribed ideas of gender only come about through enforced stereotypes and expectations, rather than being predetermined ideas. In this way, Monica breaks the mold of predetermined ideas of both masculinity and femininity.

From a young age, Monica exhibits a profound affinity for basketball, a sport traditionally associated with masculinity. Her natural talent, determination, and passion for the game become the cornerstone of her identity, highlighting how her engagement in this particular activity challenges the conventional expectations of femininity.

Monica's embodiment of athleticism disrupts the societal notion that certain sports are inherently masculine. She defies the prescribed boundaries of what it means to be a girl by embracing basketball wholeheartedly, showcasing physical prowess and competitiveness commonly attributed to masculinity. Her performance in the realm of basketball not only challenges but reconfigures the boundaries of gendered activities, exposing the fluidity and constructed nature of gender roles.

Throughout the film, Monica's dedication to basketball blurs the lines between conventional notions of femininity and masculinity. She navigates the basketball court with skill and determination, not conforming to the passive image often associated with women in mainstream media. Instead, Monica actively challenges this notion, illustrating that gender identity is not predetermined but rather shaped through actions and performances.

The concept of performative gender is vividly demonstrated in Monica's actions, which defy societal expectations and challenge the status quo. Her passion for basketball becomes a platform for the reimagining of gender norms, prompting audiences to reconsider the limitations imposed by societal constructs.

Furthermore, Monica's embodiment of performative gender extends beyond her actions on the court. Her refusal to adhere to traditional gender roles within romantic relationships and her unwavering commitment to her career aspirations exhibit a deliberate performance that transcends prescribed gender norms.

In essence, Monica's character in Love and Basketball becomes an embodiment of Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity. Her passionate engagement with basketball challenges and reshapes traditional gender roles, presenting a compelling narrative that questions the rigidity of societal expectations surrounding femininity and masculinity. Through Monica's journey, the film invites audiences to reconsider the performative nature of gender and the fluidity inherent in its expression.

Monica's bold defiance of traditional gender roles, intricately explored within the film's narrative, segues seamlessly into the broader exploration of societal stereotypes through character portrayals, aligning with Stuart Hall's reception theory and the film's approach to challenging norms. While Monica's passionate engagement in basketball serves as a catalyst for questioning and reshaping gender norms, the subsequent narrative unfolds, compelling audiences to reconsider ingrained societal stereotypes, encouraging critical decoding of these moments, and fostering a more inclusive understanding of gender dynamics and relationships.

Love and Basketball consistently challenges societal stereotypes through its narrative and character portrayals, aligning with Stuart Hall's reception theory about decoding media messages. Several instances stand out, prompting audiences to resist or reshape prevalent societal norms. By operating within the basketball realm, which is often a male-dominated space, while empowering Monica, the film “acknowledges the legitimacy of hegemonic definitions to make the grand significations (abstract), while, at a more restricted, situational (situated) level, it makes its own ground rules” (Hall, 516).

One poignant example is Monica's rejection of the 'damsel in distress' trope within romantic relationships. Unlike conventional portrayals of women waiting for men to define their lives, Monica asserts her agency in shaping her destiny, refusing to conform to the passive roles often depicted in mainstream media. Her determination to prioritize her career aspirations over conforming to traditional gender roles challenges the audience's expectation of female characters, inviting them to decode this rejection as a departure from typical gender norms.

Moreover, the film subverts the stereotype of women as mere objects of desire by presenting Monica as a multifaceted character. Rather than being reduced to a passive love interest, Monica's character is layered, showcasing her emotional depth, ambition, and imperfections. Audiences decoding these nuances witness a departure from the traditional male-centric gaze, reshaping the perception of female characters in cinema.

Additionally, the film challenges the stereotype that sports are exclusively a male domain. Monica's journey in pursuing basketball as a career confronts the societal notion that certain sports are inherently masculine. By showcasing her athleticism, competitiveness, and love for the game, the film defies the notion that women are less capable in sports, prompting audiences to decode these moments as a challenge to gendered stereotypes in athletic pursuits.

Furthermore, the depiction of Monica's and Quincy's relationship resists conventional gendered dynamics. The film portrays emotional vulnerability in Quincy's character, breaking the stereotype of male emotional detachment. Monica and Quincy's relationship evolves beyond the constraints of traditional gender roles, inviting audiences to decode these nuanced interactions as a reimagining of relationships that transcend societal expectations.

Moving from the film's challenge to societal norms through characters to its portrayal methods, Love and Basketball offers a complex view. It tackles gender expectations while following Monica's journey, challenging traditional movie ideas about gender and romance. This allows for a detailed look at both its social messages and its approach to moviemaking, going beyond usual portrayals in mainstream cinema.

The film intricately navigates the male gaze in its portrayal of Monica's athletic prowess and romantic interactions, employing cinematography that both aligns with and challenges traditional conventions. When showcasing Monica's basketball skills, scenes often focus on her agility and dedication without overt objectification. For instance, in the basketball court sequences, the camera skillfully captures Monica's movements, emphasizing her talent and determination. During pivotal basketball moments, such as her winning shot, the camera follows her actions, highlighting her skill without reducing her to a mere object for the male viewer's gaze. This deliberate framing invites the audience to appreciate Monica's athletic abilities and passion for the game without exploiting her physicality.

Conversely, in romantic interactions, the film occasionally aligns with elements of the male gaze seen in traditional cinematic tropes. For instance, during intimate moments between Monica and Quincy, certain scenes utilize close-ups and framing that could cater to a male-centered perspective. However, the film also subverts these norms by ensuring Monica's character maintains agency and complexity within the narrative. In moments where Monica navigates her romantic relationship, the storytelling consistently portrays her as an individual with desires, emotions, and aspirations, transcending the traditional objectification often associated with the male gaze in cinematic portrayals of women. For example, the scene where Monica confronts Quincy about his infidelity portrays her emotional depth and agency, shifting the focus from mere objectification to a complex depiction of her feelings and choices within the relationship.

Overall, the film carefully balances between conforming to and challenging aspects of the male gaze. Through specific examples in cinematography and narrative framing, the film acknowledges prevalent cinematic tropes while also presenting Monica's character with depth, agency, and emotional complexity. The deliberate portrayal of Monica's athletic talent without excessive objectification and the nuanced handling of her romantic interactions contribute to a layered depiction that both engages with and transcends elements of the male gaze prevalent in cinematic storytelling.

Love and Basketball skillfully encapsulates Monica's profound evolution from a spirited young girl to a resolute athlete, challenging rigid gender expectations and redefining societal norms. Her ardent pursuit of basketball, intertwined with her resilience against conventional standards, serves as a beacon, reshaping perceptions of athleticism and established gender roles. Throughout the narrative, the film carefully delves into Monica's character, granting her a multifaceted portrayal brimming with depth and autonomy. Concurrently, her relationship with Quincy forms an evocative canvas that subverts traditional gender dynamics. The movie beckons audiences to engage critically with its compelling storyline, urging contemplation on nuanced portrayals that disrupt and reconstruct prevalent stereotypes. Monica's unwavering commitment to basketball and her intricate romantic journey within Love and Basketball serve as a powerful commentary, challenging societal norms while meticulously navigating between conforming to and diverging from cinematic conventions. This intricate dance within the film's narrative fabric transcends conventional gender depictions, carving an indelible mark in the realm of mainstream cinema with its layered and authentic portrayal of a woman's journey through sport, love, and self-discovery.

Citations:

Butler, Judith. “Gender Is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion.” Taylor & Francis, September 3, 2014. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/mono/10.4324/9780203760079-5/gender-burning-questions-appropriation-subversion-judith-butler.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse.” Semantic Scholar, September 1, 1973. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Encoding-and-Decoding-in-the-television-discourse-Hall/9d8d680436345535ae2598f9e6786c68d4143f9b.

Love & Basketball Directed by Gina Prince-Blythewood, performances by Sanaa Lathan and Omar Epps, 2000.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In what ways does the character of T'Challa embody the conflict between tradition and progress, especially in his role as both a protector of tradition and a forward-thinking leader?

BLACK PANTHER

youtube

Ryan Coogler's "Black Panther" (2018) stars Chadwick Boseman as T'Challa, the Black Panther and King of the fictional African nation of Wakanda. The afrofuturistic nature of this civilization, with it being a technologically advanced society not conquered or colonized, and the focus of the film being solely on Black characters, and with this film also being a large budget Marvel movie, was a defining moment for Black America, making this film so significant, as in both science fiction and superhero movies alike, the lack of representation is apparent with people of color characters generally being cast aside as a side character, so for a Black character to not only be the main character but have many supporting characters and prevalent characters also be Black, with a plot surrounding an afro-futurist society is very significant.

Helen Addison-Smith's "E.T Go Home: Indigeneity, Multiculturalism, and 'Homeland' in Contemporary Science Fiction" broadly discusses the idea of 'alienness' in science fiction and the implications of otherness, expressing that; "however, unlike the otherness of these creations (cyborg, monster), the alien's otherness is biological" (Addison-Smith, 15). These implications of biological alienness in "Black Panther" can be seen through antagonist Eric' Killmonger' Stevens. The biological separation between citizens of Wakanda and African American Killmonger is apparent even down to physical appearance, with Killmonger having many scars, which he explains mark how many people he has killed. Additionally, these scars are also of cultural significance, as they were inspired by the Chambri Tribe from Papua New Guinea, and these scars are celebrated within this tribe as they are seen as a way to showcase strength and perseverance. However, within the film, these scars help further Killmonger's 'otherness' in the society of Wakanda, exhibiting the oppression he has faced in America, leading him to want to fight for Black liberation initially and initiating a takeover of Wakanda from his cousin T'Challa. Biological factors such as birthplace help to give Killmonger and T'Challa very separate identities, as one is an African American citizen, and the other an African citizen, and this furthers Killmonger's perceived identity as an 'alien' figure as his homeland is different from the other characters within this film.

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the film critique capitalism, consumerism, and the commodification of identity through its portrayal of the "white voice" and the rise of WorryFree as a dystopian corporation?

Sorry To Bother You - Roundtable Presentation

youtube

Sorry to Bother You (Boots Riley, 2018), follows Cassius Green as he begins work as a telemarketer. After months of late rent and struggling to get by, he settles for the only job that will “hire anyone”. At first, Cassius struggles to get through to anyone over the phone and is constantly being hung up on. Everything changes when he receives some advice from an older coworker, Langston. He instructs Cassius to use a “white voice” over the phone to get customers to listen to him. Langston demonstrates his ability to put on an almost cartoonish voice that immediately masks his Blackness to anyone who can’t see him. Cassius resists at first, but once he tries it there is no going back.

The introduction of the “white voice” is where we see the science fiction piece start to appear. The voice is completely unrealistic, clearly not the actors actually talking. It is as if their voices are being overdubbed by a squeaky overly animated white guy, and the voice is exactly the same for Cassius and Langston. Once Cassius starts succeeding at his work, his calls place him in the room with people, someone will answer the call on the toilet and suddenly Cassius is there with them, adjusting the settings on their bidet for them as he rambles about phone providers. Cassius is able to use phone to bypass his identity, creating a new imagined one through the surrealism of the film. Cassius and Langston are not just doing a voice, they are transporting themselves into another world where they escape some of the anxieties of racial identity and are able to benefit from the capitalist systems they exist within.

Cassius is so wrapped up in his own success that he suddenly finds himself working with his boss to create a perfectly dehumanizing workplace and against his fellow employees who are fighting for fair treatment in their field. Eventually his conscience catches up to him and he realizes he has been living in an alternate world, one that is in no way real. Sorry To Bother You presents a surrealist take on our dystopian, racist, capitalist world that makes you think about what universe you are living in.

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the film balance its satirical take on pop culture, consumerism, and the pursuit of pleasure with deeper introspections on the characters' emotional journeys?

Race in the Imaginary: Nowhere (1997) dir. Gregg Araki

"L.A. is like... nowhere. Everybody who lives here is lost. "

-The opening quote of Nowhere

"In general, these films worry that the most violent and degraded acts are possible to those who do not inhabit a home or homeland."

-Helen Addison Smith, "E.T. Go Home: Indigeneity, Multiculturalism and ‘Homeland’ in Contemporary Science Fiction Cinema"

Gregg Araki describes his film Nowhere as "Beverly Hills 90210" on acid. Nowhere follows a number of uniquely-named, all somewhat inter-connected teenagers (Lucifer, Dingbat, Egg, Jujyfruit...) in Los Angeles over the course of one day as they engage in an aimless cocktail of drugs, sex, polyamory, BDSM, and parties. The world of the film is in constant flux between reality and fantasy (and it is very, very, very queer). Everything is extremely heightened: there are lengthy, gratuitous sex scenes, a seemingly unlimited access to space, an abundance of drugs, and vast, artistic bedrooms that real teens would only dream of.

In my interpretation, the film's world is an external representation of the teens' imaginations and their feelings of an endless, indestructible youth. While this world is a step above reality for the viewer, it is real to the characters. However, this overindulgence is not without it's consequences. The first half of the film is a sort of queer, sex-positive utopia seemingly free of prejudice in which the teens can have sex with whoever they want, go wherever they want, and so on. This all seems to crumble in the second half of the film, as the teens' endless consumption unravels into overdose, sexual assault, suicide, violent fights, and broken hearts. Araki does not seem to be prudish or critical of this queer nomadic lifestyle, though. He seems to posit that this imaginative world is sadly incompatible with the "real world" of capitalist society at the turn of the century.

Now for the sci-fi. Unbeknownst to every character except Dark, the day on which this film takes place is sort of Judgement Day; the last "normal" day before aliens come to take over the planet.

Dark is the main character of the film, and offers some narration through diary entries and videos he takes of himself and his friends. He is played by James Duvall, a multiracial actor. Dark becomes increasingly unhappier as his girlfriend Mel spends more and more time with her girlfriend Lucifer, who he hates. He grows weary of their indulgence sexually-open arrangement, simply wanting to fall in love and be committed to one person that will anchor him in a world he feels lost in. As he gets more disconnected from Mel, he finds himself infatuated with Mongomery, a boy who goes to school with the teens but who Dark knows little about.

youtube

At the same time as Dark's discontent with his lifestyle grows and he finds himself falling in love with Montgomery, he sees a bunch of giant alien creatures roaming around the city, abducting people. Dark is the only character able to see these aliens, which seems to be no coincidence alongside the fact that he is the only character verbalizing any anxiety about the future and the teens' lifestyle. In one diary entry, he says:

"I feel like I’m sinking deeper and deeper into quicksand, watching everyone around me die a slow, agonizing death. It’s like we all know, way down in our souls, that our generation is gonna witness the end of everything. You can see it in our eyes."

In the final scene of the film, Dark returns home after an empty night of partying and a fight with Mel. Montgomery appears at his window and tells Dark that he was abducted and tested on by the aliens. The two boys lie together on Dark's bed and confess their love, promising to never leave each other. Just when it seems like Dark has found what he has been longing for, Montgomery goes into a violent coughing fit and explodes, leaving a bug-like alien in his place that crawls out of Dark's room, and the movie ends.

youtube

While the aliens in Nowhere are not necessarily representative of a racialized Other according Addison Smith's analysis of Sci-Fi films, the impending doom of an alien invasion and Dark's isolating anxiety is quite in line with Addison-Smith's reading of home and homeland. Araki's identity as Japanese-American director and Duvall's as a multiracial American actor are factors in this reading of the film. Since this film is thus told from a mixed/multiracial perspective, the its anxiety is not surrounding the (white/Western) fear of "losing" a home to outsiders, but the fear of not belonging to any one home in the first place.

Addison-Smith writes:

"For many people in self-avowedly multicultural nations such as

the United States, their status as migrants, be it forced or economic, recent or later generational, means that 'home’ has become a complex, multiple and sometimes fraught notion. That such multiple belongings to place is not confined to recent migrants can most immediately be seen in the labelling of many ethnic groups through the joining of two place names (African—AmericanJapanese-American)" (28).

Araki uses Los Angeles as an unstable home in this film (note the opening quote at the top of this post). He plays upon the notions of transplants to the city, and the stereotypes that the city and its inhabitants are vain and superficial. The characters move throughout the city at will, with no connection to any particular space. Actual homes are places of confinement and depression (both the suicides in the film occur in character's bedrooms).

I read that Dark's ability to see the aliens is a representation of his sense of displacement and anxiety for the future. When Montgomery enters his room and the two share an extremely intimate, tender moment, his room finally begins to feel like home, rather than its previous role as a space for his lonesome brooding and masturbation. But when Montgomery explodes as is replaced by an alien, Dark's vision of home and someone to share it with also figuratively blows up in his face; home feels impossible.

Finally, Montgomery's objectification by Dark's infatuation and his identity as a white queer man seem to be an inversion of both romance and Sci-Fi tropes. Montgomery seems to occupy both the role of the "Manic Pixie Dream Girl" in Dark's desire to be saved by him, and the racialized alien Other in his mysteriousness and his constant affiliation with the aliens. Addison-Smith writes, "An alien is easy to identify, and particular judgements about them are thus easily drawn from their appearance alone, so rooting their ‘racial nature' in their biology" (27). Montgomery definitely stands out in this world. He has different colored eyes, is always dressed in white, appears to Dark miraculously by a sign that reads "God help me," and, unlike very other character, is quiet and keeps to himself. He is alien and even an angelic figure to Dark, a unique representation against Addison-Smith's notions of the racialized alien as either invader or teacher.

The entire movie Nowhere is on Youtube! I think it's really great, but there's a ton of trigger warnings (sexual assault, drug abuse, suicide, eating disorders, physical assault, gore). The quality is also very bad. Proceed with caution.

youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

In what ways do the characters of Moses and his friends undergo transformation throughout the narrative, challenging stereotypes and assumptions about youth in inner-city environments?

Roundtable 2: Race in the Imaginary and Attack The Block (2011)

youtube

Attack The Block (2011), directed by Joe Cornish, is a sci-fi film that takes place in South London, and follows a group of trouble-making teenagers who must defend themselves and their apartment complex from extraterrestrial beings. The film begins with the group of teenagers attempting to rob an innocent woman, but their attempt is cut short when something falls from the sky, and lands in a nearby car. Once the woman runs off, the boys go to investigate the car, and stumble upon an alien creature who lunges at them. Originally, it seemed as if the villains were the teenagers, however the landing of the alien establishes the real danger of the story. After they take off the bandanas they had obscuring their faces, and we get a glimpse at their comradery, it's obvious that they are just children.

The boys' failed robbery from the beginning comes back to haunt them, as the woman, Sam, contacts the police to find them. Now, not only does the group have to run from aliens, but the police as well. As the group runs for their lives from aliens, two police officers manage to grab hold of the group's "leader", Moses, played by John Boyega. This is one of many times that the police chase after them, as if they are the aliens, rather than catching the actual aliens that are killing civilians. Here, a comment is being made on the fact that teenage boys of color, specifically Black boys are disproportionally sought after by law enforcement. Moses even goes, to say "I reckon, the Feds sent them anyway. Government probably bred those things to kill black boys. First they sent in drugs, then they sent guns and now they're sending monsters in to kill us”, showing that even in a world where rampaged aliens are killing humans, children of color are seen as the threat.

Most of the film takes place inside, or just outside of a giant housing project in South London, known as, “The Block”. We learn that this is where almost all of the boys live, and a place they feel is their duty to protect, often stating "nobody fucks with Block"(7:09). The building is akin to an eery, futuristic fortress, however it is a clear home for the boys. Though the boys have different personalities, and we get brief glimpses into their differing home lives, The Block marks a universal place of belonging for them. A place where identity is characterized by protecting one another from the impending threats of aliens and law enforcement, both of which have no regard for the boys as people. Though they are seen merely as thugs by law enforcement, the movie works to bring humility to them through giving depth to their personalities, and addressing the socioeconomic context of their lives.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

In what ways does the film explore the dichotomy between the Draags and the Oms as a reflection of power dynamics, subjugation, and the desire for autonomy?

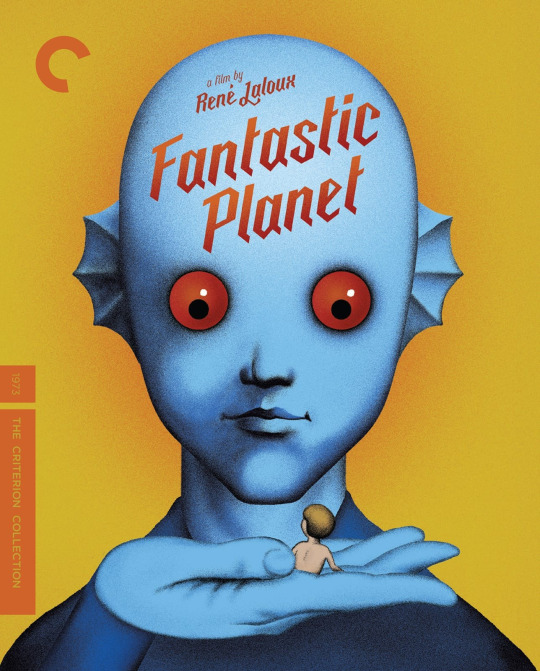

La Planète Sauvage (1973) Race in the Imaginary

René Laloux’s La Planète Sauvage (1973), an experimental animated science fiction art film, is as strange as it is dense with implications. The politically charged dissonance of psychedelia combined with the film’s Dali-esque surreal cutout stop-motion animation universe, realized by French avant-garde artist Roland Topor, has solidified this film as a seminal work of animation and a cult science fiction feature. The film is set in the hallucinatory landscape of the planet Ygam, where gargantuan blue humanoid creatures called Draags who rule the planet enslave humans (called Oms–a play on the French homme)--Terr, an Om who has been kept as a pet since Traag children killed his mother in his infancy escapes from his child captor and bands together with a band of radical escaped Oms to resist the Draag regime and impending genocide. The film is markedly allegorical for its use of imagined alienness to establish otherness and marginalization, and the techniques the Draag use to subordinate the Oms evoke historically significant racist discriminatory practices. Simply, it feels like a movie that is bluntly about something beyond what it appears to be, and the slight heavy-handedness of its messaging reifies its goal of engaging in racial discourse.

The racial politics of Fantastic Planet are strange in that the broadness of the trenchant sociopolitical commentary imminent in the dynamic between oppressor and oppressed has led critics to draw comparisons between the plot and the narrative around “animal rights” and the (mis)treatment of domesticated animals, yet the human-ness stitched into the film’s fabric positions it as a text specifically interested in the ways humans create divisions among themselves. The Draags and the Oms, despite their vast difference in physical size, do resemble one another and take on different forms of the corporality of a human being, and for this reason and many others, Fantastic Planet seems to be a film about how we could recognize ourselves in one another and still splinter into factions and enforce senseless violent domination.

Terr’s captor, a girl named Tiwa, has given him a collar to control him as he attends “school” with her, which involves her wearing a headset that transmits facts into her brain, and a defect in his collar inadvertently allows him to learn the same knowledge as Terr, knowledge he ends up using to save the Oms. Intelligence is the gateway to capital in Ygam and the Draags are highly intellectualized beings who pride themselves on their inborn wisdom and biological superiority that allows them to far outdo the meager Oms in their knowledge–the film comments on the complications of the racialized bioessentialist understanding of knowledge that would posit that being smart, and subsequently having value, is a fixed innate biological trait. The Oms navigate the world through cunning, outwitting the Draags practically in ways they might fail to do so intellectually and the Draags and Oms counter one another in the film on what “counts” as knowledge: the Draags favor transcendental meditative practices that imbue them with highly complex perspicuity, whereas the Oms argue that their knowledge is more useful for the ways it enables them to survive despite their circumstances. The Oms are made alien not only through their physical inferiority but also because they exist in a society that was not built for them. Fantastic Planet depicts an idea of home that is stringent upon exclusivity and requires technical superiority to belong; shoring up racial politics, Fantastic Planet deploys a social constructionist standpoint that colors these divisions as the products of structural forces benefitting only those who erected them.

youtube

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the character of Lenny Nero navigate the moral dilemmas associated with the use of the SQUID technology and its impact on personal privacy and ethical boundaries?

Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995)

Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995) is a science fiction thriller set in Los Angeles during the last two days of 1999. With the general consensus being that the end of the world is imminent: Los Angeles has devolved into a warzone of debauchery, violence, and crime. The film centers around ex-cop Lenny, who deals SQUID devices on the black market. SQUIDS are illegal devices that record peoples’ physical sensations and memories from their cerebral cortex onto a mini CD disc that allows them to be played back and experienced by anyone.

Lenny’s ex-girlfriend Faith’s friend Iris ends up recording police murdering black rapper and activist Jeriko One. The audience has only briefly been introduced to Jeriko via a speech he gives on television protesting the police state that Los Angeles has fallen into and pushing for peace. Since Jeriko’s character is not further developed before he is killed, he exists as more of a symbolic placeholder for all of the innocent black people that police have murdered. Iris is then chased by police but ends up getting the tape to Lenny before she is brutally raped and murdered. Lenny and his driver/bodyguard/friend Mace (who is also in love with him) then have to run from everyone who’s trying to kill them and Mace gets the tape of the murder to the police commissioner.

It’s interesting that even in this apocalyptic, end-of-the-world setting, racially motivated violence and police brutality are still prominent. Bigelow has discussed in interviews being motivated to begin production following impactful incidents in the 90’s such as the Lorena Bobbit trial and the Rodney King verdict and the riots that followed in 1992. Multiple of the characters in Strange Days are overtly racist (ie. the cops/murderers), but more subtle racism also permeates throughout. When trying to figure out how to get the video of Jeriko’s murder to the public, Mace and Lenny go to Lenny’s “friend” Max (who will turn out to be an awful person) for help. Max says simply that Lenny and Mace should not show the tape because there will be riots. In this moment Max is willing to silence the story of police murdering a black man to avoid causing a more than warranted uprising.

Bigelow seems to have intentionally sought to explore the intersection between race and gender as she stated that she created Mace’s character to examine "valuable connections between female victimisation and racial oppression." Mace proves to be stronger and more confident than Lenny; she repeatedly saves their lives and gets them out of tricky situations, yet she is still reduced to the role of his bodyguard/driver, and not given much of a story outside of Lenny’s world. At one point when they are in the car, she points out this dynamic saying “driving Mr. Lenny,” a reference to the film Driving Ms. Daisy (Bruce Beresford, 1989). Mace is additionally in love with Lenny because he stepped in and helped her take care of her son when the kid’s father was no longer around. Despite Mace being a strong, smart, and badass, black woman, her story is somewhat reduced to being the white man’s sidekick. She is also in love with Lenny for the entire film and when they eventually kiss at the end, it feels like she has now only existed to be his love interest.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the narrative balance the scientific quest for proof of alien life with the human emotional journey of the characters, particularly in their reactions to profound discoveries?

Contact Viewing Response

Contact, directed by Robert Zemeckis and released in 1997, follows the story of Ellie Arroway, played by Jodie Foster, who is an astronomer looking for proof of extraterrestrial life in space. Her dream began at a young age with the help of her father, who suffered a heart attack when she was nine years old but she persevered and continued to follow her dream in honor of him. As a young adult, Ellie started working for the SETI program (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), but the program is threatened to be terminated by the President’s science advisor. Four years after starting to work for SETI, Ellie discovers a signal coming from the star Vega, and after further investigation, her team decides that this transmission should be strong enough to allow them to travel to Vega by penetrating the Earth’s ionosphere and sending them back to Earth. She decodes the signal and finds that it contains information about a machine that can be built to transport an individual between space. Human made technologies are utilized in this film, which are used to connect with the extraterrestrial world.

youtube

Even though this film stars a female lead, it does have a predominantly male, white cast, and one of the only characters of color is Rachel Constantine (played by Angela Bassett), who is the National Security Advisor to the President. She is the only other predominant female figure in this movie alongside the lead. Her role in the government’s involvement with the extraterrestrial contact mission and construction of the machine is very significant and she is a very authoritative figure within the film.

Contact brings up questions surrounding religion and science, as when controversy arises over the machine being built, religious extremists strongly oppose the mission due to claims about it challenging their faith and humanity’s place in the universe. The machine ends up being bombed on the day of its launch, preventing any sort of contact with extraterrestrial intelligence and unknown entities. Later, a second machine is secretly constructed in Japan and Ellie is chosen for the mission. She travels through multiple wormholes and finds herself on a beach similar to one from her childhood, where she sees an alien-like figure that appears to be her deceased father. In a way, Ellie’s home is with her dad, whether or not that is physically on Earth or on Vega, reuniting with him as a young adult in a strange sort of dreamy way. After reconnecting with him, she loses consciousness and finds herself back in the machine’s pod, with the mission team trying to contact her through her recording device. She tells them that she was gone for 18 hours, but they insist that all they received was static noise for just a few seconds.

Despite doubt over the success of this mission, it is later discovered that although her recording device only recorded static, it was indeed 18 hours worth of it. She was continuously told she must have hallucinated and that because she did not have any physical evidence, it could not have been real. Often in the scientific field, women are often doubted and not taken seriously in their research and discoveries, so maybe this testimony would have been received differently had it been a man making these claims. In her testimony, Ellie claims that this mission impacted her humanity and everything she has ever known as a human being, which is a recurring theme of this film.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the film utilize the diverse abilities of mutants to showcase the strength of unity and diversity in overcoming adversity?

X-Men: Days of Future Past

In a dystopian future, mutants face extinction at the hands of the Sentinels, killing machines developed to detect the mutant gene and kill anyone that carries it. The Sentinels are part of the Sentinel program, created by Dr. Bolivar Trask in the 70s. The Sentinel program was approved following the assassination of Dr. Trask, which was carried out by Mystique. Following the assassination, she was kidnapped and her DNA was obtained and altered to advance the Sentinel program. With her powers of transformation, the Sentinels became more advanced killing machines, escalating the extinction of the mutants. The last of their kind, a small group of mutants fight off the Sentinels while Xavier and Magneto plot to alter history by preventing Trask’s assassination and Mystique's kidnapping. Kitty is able to send Wolverine’s consciousness back in time to 1973 to try and prevent Mystique from going after Dr. Trask. Wolverine wakes up in his younger body and he recruits some mutants to help him, among them Charles Xavier (Professor X), Hank (Beast), and Eric (Magneto). The plan fails, Dr. Trask survives the assassination attempt and he warns President Nixon of the danger of mutants and he approves the Sentinel program. During the assassination attempt, Hank and Mystique reveal themselves as mutants to the world and the Dr. Trask gets Mystiques’ DNA.

The different identities in the film are established through the mutant gene which only few people carry. They are singled out and labeled as “mutants,” separating them from the rest of humankind. Mutants hide their abilities and the fact that they are mutants in fear of prejudice and hatred. The events that unfolded in the first assassination attempt on Trask helped push a narrative where mutants are considered dangerous and must be eliminated, therefore getting the approval for the Sentinel Program. Mutants are now hunted by human technologies thanks to the prejudice of one man, his creations, and the narrative he pushed. Before the technology developed for the Sentinel program, mutants were able to live peacefully and unnoticed among humans.

In the final act of the film, Mystique once again goes after Trask at an event in Washington D.C. where the Sentinel program is unveiled. A fight breaks out between Xavier, Beast, and Wolverine who want to stop Mystique, and Magento who has taken over the Sentinels and intends to kill everyone at the event. Xavier persuades Mystique to spare Trask and she saves President Nixon from Magneto. This results in the Sentinel program being shut down, altering history and making Mystique a hero.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the film challenge traditional hero tropes and notions of redemption through its portrayal of flawed characters and morally gray situations?

District 9

youtube

"District 9" is set in an alternate version of Johannesburg, where a massive alien spacecraft hovers above the city. The extraterrestrial occupants, known derogatorily as "Prawns," are resettled into a government-controlled district. The narrative centers around Wikus, a bureaucratic functionary assigned to oversee the forced relocation of the aliens. When a mysterious alien substance alters Wikus's biology, he becomes a target for both the government and the aliens. Fleeing to the district he once oversaw, Wikus forms an uneasy alliance with an intelligent alien named Christopher Johnson.

How does the film use human technologies and/or imagined alienness to establish different identities?

The film employs a pseudo-documentary style, blending real-world news footage with filmmaking. The human technologies, such as military weaponry and surveillance equipment, highlight the power dynamics between humans and aliens. The alien technology, on the other hand, is portrayed as highly advanced and mysterious, emphasizing the contrast between the two species.

The imagined alienness is crucial in shaping the narrative's socio-political commentary. The physical appearance of the aliens, resembling insect-like creatures, contributes to their dehumanization. This visual otherness reinforces the xenophobic attitudes prevalent in the film's fictional world, drawing parallels to real-world issues of racism and discrimination.

How does film de-individualize and/or biologically reify alien characters that mimic racial prejudicial and discriminatory practices?

The film de-individualizes the alien characters through various means. Firstly, the aliens are collectively labeled as "Prawns," stripping them of individual identities and reducing them to a derogatory, dehumanizing term. Secondly, their living conditions in the segregated district contribute to their de-individualization, as they are confined to shantytowns, reinforcing a sense of collective suffering.

In what ways does the film depict home for the characters?

For the humans, Johannesburg represents their home, and the arrival of the aliens disrupts this sense of familiarity. The district where the aliens are confined becomes a physical manifestation of their displacement, a makeshift home reflecting their marginalized status.

How does technology inform definitions of home/land, indigenes, and aliens?

The powerful human military technology reinforces the idea of humans as the dominant kind, asserting control over the land. The alien ship, initially a symbol of hope for the aliens' return home, becomes a source of conflict as they all vie for control.

The film suggests that technology, whether human or alien, is a double-edged sword that can be both a tool for empowerment and a catalyst for conflict. The question of who controls the technology becomes central to the characters' struggles for autonomy and a sense of home.

In what ways do the character relations reflect anxieties of racial identity, racial mixing and/or passing, migration, and invasion and/or colonization?

The segregation of the aliens in a specific district echoes the forced segregation of racial groups in apartheid-era South Africa. The relationship between the human protagonist, Wikus Van De Merwe, and the alien Christopher Johnson challenges preconceived notions about racial identity and cooperation.

Wikus undergoes a physical transformation that blurs the lines between human and alien, reflecting the film's exploration of the fluidity and constructed nature of racial identities. The tensions between humans and aliens also mirror historical anxieties about invasion, colonization, and the fear of the unknown "other."

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

What impact does the film's use of special effects and creature design have on the audience's immersion in the world of aliens and secret agencies?

Men in Black (1997)

Men in Black details Agent J’s first mission for the eponymous government agency who regulates alien activities such as the immigration of said aliens to Earth and any threats they may pose. Agent J and his mentor, Agent K, remedy an alien diplomatic crisis and prevent the disintegration of Earth.

youtube

In Men in Black, many aliens pass for humans and have adopted disguises to help them live among humans. However, many of them still have their alien features that set them apart from the human population ranging from double pupils with gills, regenerative limbs, animalistic features, or being miniscule. Once revealed to be alien, however, it is impossible to unsee them as aliens and there is an uneasy horrificness at these strange creatures.

The main antagonist is a newly landed alien who is portrayed as quite volatile and hostile towards all humans. His species is literally referred to as “bugs.” He adopts a human skin that gruesomely decays throughout the movie and at the end, reveals his true appearance which is of a monstrous, huge cockroach like creature. This is the main alien that is consistently shown throughout the movie despite their depiction of other aliens as overall helpful, intellectual, and peaceful refugees. As a result, the audience focuses on the evilness and non belonging of aliens. This is similar to the typical reactions towards immigrants because current residents are not welcoming to new people especially people of color who are deemed not worthy of a place in the community as they are disgusting or contaminating (like the alien protagonist) and would ruin their current balance.

Citizens are also scared of immigrants having the same privileges and opportunities as them or even succeeding more than them, thus endangering their own chances which also applies to the aliens in the film. Most of the film’s aliens pass for humans which would freak out Earth’s human citizens as they are being threatened by these new unexpected populations. The Men in Black agency actually already has limited these aliens' success as the agency profits off the technology they confiscate (steal) from the aliens like Velcro. This is representative of how it is the aliens “teachings rather than their continued presence that is vital” especially because Earth is doing them a favor by providing the aliens refuge (Addison-Smith 31). The emphasis of the aliens seeking refuge on Earth is also an example of how the aliens are homelessness and have to rely on New York and its multiculturalism to blend in and survive. However, they are not completely at home and secure. Like human immigrants in our society, they have to build new lives in their new world due to their escape from their legitimate homeland and have to assimilate to the new society and current residents.

In addition to this migration and passing of aliens as humans (akin to racial passing), Men in Black explores alien invasion and how aliens can lead to the downfall of the very planet that protected them. Firstly, the whole crisis is caused by an unsanctioned alien who landed and started wreaking havoc the moment it got to Earth. This causes an alien species ship to come to destroy Earth, even though Earth was a refuge for one of their royalty. Throughout the film, there are also many aliens who have decided to flee Earth because of its impending doom and leave it to be destroyed even though it was a safe haven for them as refugees. This mirrors the uncertainty of the loyalty of immigrants to their new home or rather their self-preservation or old motherlands. However, it is understood because, like immigrants, aliens “are always overwhelmed numerically by humans” (Addison-Smith 32). As seen in the Men in Black agency, aliens are not in any leadership positions. The majority of the aliens who help the agency are treated very hostilely in return for their services and intel. Aliens are mistreated by the only human group that knows of their existence and could validate that existence. The aliens in Men in Black reflect the opinions of immigrants and refugees in regards to how their differences, their lack of belonging in their new land, and the lack of human empathy is emphasized.

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the film utilize the post-apocalyptic setting to explore themes of survival, redemption, and the human condition?

Roundtable 2: Race in the Imaginary and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

youtube

Mad Max: Fury Road is a 2015 film by George Miller that many hail as a feminist manifesto. It’s set in a barren wasteland, supposedly the not-too-distant future after the Water Wars and the depletion of oil. It follows Max after he’s captured by Immortan Joe’s War Boys and Furiosa’s attempt to flee and free Immortan Joe’s wives. It involves endless perfectly edited practical car chases, Nicholas Holt in so much makeup you can’t recognize him, and simply named characters and places like the “Bullet Farm” and “War Boys.”

It is clear from the very beginning that Immortan Joe is evil: his first scene involves close-ups of his battered and radiation-poisoned body. He is the alien because, according to Helen Addison-Smith's article, an “alien is easy to identify, and particular judgments about them are thus easily drawn from their appearance alone” (27). Several members of his “team,” like his son Corpus Colossus or The People Eater, also have emphasis put on their atypical bodies. Max and Furiosa, on the other hand, are not aliens: they’re conventionally attractive, able-bodied, recognizable humans. While Furiosa is missing her left forearm, she has a mechanical prosthetic and there is no attention drawn to this. Through the lens of Addison-Smith's article, it could be argued that Miller uses atypical bodies to signify alien- and otherness.

youtube

Another very important point to bring up is the setting of this film. Though never explicitly stated, it is set in the Australian outback, a country that is home to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations and was stolen by the British. As far as I know, Courtney Eaton (Cheedo the Fragile), whose mother is of of Chinese, Cook Island and Māori descent, is the only indigenous actor in the film. Addison-Smith addresses this phenomenon, writing that “The diasporic subject has a sense of belonging to a place where [they do] not live … it ‘is the myth of the (lost or idealized) homeland, the object of both collective memory and of desire and attachment, which is constitutive to diasporas’” (28). A large part of the film’s plot is Furiosa and The Wives returning to Furiosa’s “homeland”: The Green Place, home to the Many Mothers. But, for the most part, none of this land belongs to any of the characters in the film – they do not have a right to it and, at the end of the day, they caused the apocalypse that landed them in the Outback fighting for their lives.

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does the documentary-style presentation and fictional narrative intersect to create a commentary on activism, resistance, and the media's role in shaping societal narratives?

Roundtable Queries: Race in the Imaginary, Born in Flames (1983)

How does the film use human technologies and/or imagined alienness to establish different identities?

In spite of taking place in a dystopian future, there is no explicit depiction of advanced technologies. Born in Flames is set ten years after a peaceful revolution that has rendered America a Democratic socialist state. This supposed stride in progress has not stopped the oppressed from being marginalized. As a response to their oppressive conditions, a group of women-led community organizers take matters into their own hands with increasingly radical approaches. Writer-director Lizzie Borden's vision of the future suggests that dystopia might not be too different from present-day society.

youtube

How does film de-individualize and/or biologically reify alien characters that mimic racial prejudicial and discriminatory practices?