Text

Allegory of the Catholic Faith by Johannes Vermeer, ca. 1670-1672

Vermeer's religious faith is expressed most forcefully in his late allegorical painting The Allegory of Faith. The main character is a personification of Catholicism, and her appearance and gestures are taken once again from Cesare Ripa's Iconologia, this time from a figure denoting of "Faith".

But the glass orb above her head is not in Ripa's book, and it took scholars decades to work out what it meant. In 1975, the art historian Eddy de Jongh discovered the emblem – represented exactly as it does in Allegory of Faith suspended by a ribbon – in a book titled Holy Emblems of Faith, Hope and Charity by the Flemish Jesuit Willem Hesius. It was accompanied by a motto: "It captures what it cannot hold".

A short verse in the book explains that the orb is like the human mind. In its panoramic reflections, "the vast universe can be shown in something small" – and likewise "if it believes in God, nothing can be larger than that mind". The orb symbolises the mind's interaction with God.

It might be added that all of Vermeer's paintings are also like the orb, capturing passing events and ideas on their flat surfaces and sealing them for posterity. For all the paintings' exceptional skill at capturing reality, Vermeer only enjoyed very modest success while he was alive. He created about two paintings a year, and the small amount of money he could earn from it meant that he couldn't make a living by painting alone.

Perhaps his art appeals even more to us in the frenetic 21st Century because it offers a unique sense of calm. In Vermeer's scenes, time appears to freeze in the crystalline sunlight and silence descends like a dead weight. But a vivacious world of symbols pulses beneath the surface: perennially relevant ideas about art, desire, materialism and spirituality, captured by Vermeer and lying in wait of discovery.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the Summer, Congratulations by Kirill Vikentievich Lemokh, 1890

Kirill Vikentievich Lemokh, also known as Carl Johann Lemoch (Russian: Кирилл Викентьевич Лемох: 1841–1910) was a Russian genre painter and member of the Imperial Academy of Arts.

Biography

His father was a music teacher from Germany. From 1851 to 1856, he studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture under Yegor Yakovlevich Vasiliev. In 1858, he entered the Imperial Academy of Arts, where he studied history painting with Pyotr Basin and Alexey Tarasovich Markov.

Five years later, in 1863, he participated in what came to be known as the "Revolt of the Fourteen", a protest by those who preferred the Realistic style over the Classical style being promoted by the academy. As a result, he withdrew from the academy with the degree of Artist Second-Class. He joined the Artel of Artists, led by Ivan Kramskoi. Five years later, he entered an academy competition and became an Artist First-Class. From that point on, he earned his living by giving drawing lesson to aristocratic families and built an art studio in Khovrino, where he spent his summers painting.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Fruit of Love, Frucht der Liebe by Giovanni Segantini

Giovanni Segantini (15 January 1858 – 28 September 1899) was an Italian painter known for his large pastoral landscapes of the Alps. He was one of the most famous artists in Europe in the late 19th century, and his paintings were collected by major museums. In later life, he combined a Divisionist painting style with Symbolist images of nature. He was active in Switzerland during the last period of his life.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

High Noon in the Alps by Giovanni Segantini, 1892

Giovanni Segantini (b Arco, nr. Trento, 15 Jan. 1858; d Schafberg, Switzerland, 28 Sept. 1899). Italian painter, mainly of figure compositions in landscape settings, active for most of his career in the Swiss Alps. His early work was naturalistic, but from the later 1880s he developed a divisionist technique and a liking for Symbolist subjects (The Punishment of Luxury, 1891, Walker AG, Liverpool). He exhibited widely and was one of the few Italian artists of his time with an international reputation. There is a Segantini museum at St Moritz.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Punishment of Lust by Giovanni Segantini, 1891

'The punishment of lustful women' belongs to a series of paintings produced between 1891-96 on the theme of evil mothers (cattive madri). Segantini was inspired by a nineteenth-century poem, Nirvana, written by his friend the opera librettist Luigi Illica (1857-1919), who had in turn been inspired by the 'Visions' of Alberico di Settefrati, a 12th-century Italian monk from Montecassino ,whose text had also inspired the Italian poet Dante (1265-1321). Illica's poem contained the phrase 'la Mala Madre' (the bad or wicked mother with an echo similar to 'la mala femmina' or prostitute) to describe those women who refused the responsibilities of motherhood and sought a lustful, hedonistic lifestyle instead.

The souls of the women are depicted floating against a snowy background based on the Swiss Alps where Segantini spent much of his life. The grandeur and spirituality of the Alps was a constant inspiration to Segantini whose last words before he died were: "I want to see my mountains". In the painting the spirits of the women are punished for having committed the sin of abortion consciously or by neglect. Segantini had lost his mother when he was seven years old and was probably passionate to represent the trauma of the mother for the loss of her child. Segantini believed that a woman's role in life was motherhood and that a woman who objects to this was mean, bad or selfish. His beliefs drew from both religious and metaphysical ideas: the sanctity and motherhood of the Virgin Mary combined with the fertility of nature.

Segantini came from a country shaped by Catholicism. Although in his private life he never conformed to catholic doctrine, for example he refused to marry his partner and mother of his four children, his work was strongly influenced by religious ideas. What may have attracted Segantini to religion may have been the hope for a life after death. Despite the tragic and somewhat misogynistic theme of the painting, the overall effect achieved by the thread-like brushstrokes is very atmospheric and dreamy. The mysterious atmosphere set by the painting is in line with the painter's metaphysical views about the connection between human and natural life. 'The Punishment of Lust' was bought by the gallery from the Liverpool Autumn Exhibition in 1893, but the title of the painting was thought to be provocative and it was thus changed from 'The punishment of lust' to 'The punishment of luxury', although there is no evidence to support this statement. The title on the frame calls it the 'Punishment of Luxury', this is probably a mis-translation of the latin word lust, 'Luxuria'.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lady on a Balcony, Capri by John William Waterhouse, 1889

Lady on a Balcony probably dates to c.1889 when Waterhouse is known to have visited the island of Capri, probably funded by the sale of two of his most important pictures Ophelia (Lord Lloyd Webber collection) and The Lady of Shallot (Tate). In 1890 he painted The Orange Gatherers (private collection) a group of Caprese girls harvesting fruit in a similar setting of white-washed walls, citrus trees and vines and At Capri, Alfresco Toilet (Sotheby’s, New York, 20 November 1996, lot 2658). Also from this period is Arranging Flowers (private collection) and Flora (sold in these rooms, 9 December 2008, lot 129) in which Capri provided a suitably sun-bleached setting for classical idylls. Lady on a Balcony is a more direct depiction of life on Capri.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

De Spuistraat met gezicht naar het Plein te 's Gravenhage, the Spuistraat with a view of the Plein, The Hague by Floris Arntzenius

After his formal training and an additional year at the Academy of Antwerp, Arntzenius moved to Amsterdam which was considered to be the artistic centre of The Netherlands in the last decade of the 19th Century. At the Rijksacademie in Amsterdam he worked among painters such as Willem Witsen (1860-1923), Isaac Israels (1865-1934) and George Hendrik Breitner (1857-1923). Their unfolding impressionistic style was highly admired by Arntzenius and would leave a lasting impression on his own work. In 1892 he moved back to The Hague, were he would remain for the rest of his life and developed his famous city scenes. Like The Hague School painters, Arntzenius was a master in capturing light and atmosphere. He preferred painting the busy city streets to the Dutch landscape which the older generation had chosen. At that time the established painters of the first generation of The Hague School, like Jozef Israels and Hendrik Willem Mesdag, dominated artistic life in The Hague. During his time in The Hague, Arntzenius became a representative of the younger generation of The Hague School.

Arntzenius' paintings reflect the sophisticated atmosphere of The Hague around the turn of the century. He gave preference to modest sized canvases, emphasizing the intimate character of streets such as the Spui or the Wagenstraat, with figures hurrying over the wet and shiny asphalt past illuminated shop windows and colourful sign-boards. He loved to work outside in the streets and make sketches and studies of various streets in The Hague - which delivered him the nickname of: 'Straatjesschilder'. The present lot, A view of the Spuistraat, is a beautiful example of the streets in The Hague where Arntzenius was known for. Arntzenius captures the light and atmosphere of a rainy day with a variety of figures, and the dynamic representation of the buildings, are all instrumental in creating a beautifully balanced composition.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two Girls Chatting, Twee Scheveninger vissersvrouwen by Isaac Israëls

Scheveningen had developed from a calm fishing village into a sophisticated beach resort at the end of the 19th Century. The attractive village was a melting pot for wealthy tourists, artists and locals alike. The Israels family was one of many who spent their summers in there. From 1895 onwards Isaac Israels would stay with his father Jozef during the summer, who rented a villa at the Oranje Hotel. With his father and the famous artist Max Liebermann (1847-1935), who was a friend of the family, Isaac would work together. Jozef Israels concentrated on depicting the local population and the hardship of their life, but his cosmopolitan son Isaac preferred to depict the more worldly beach scenes. The wealthy and the locals strolling side by side on the boulevard. Scheveningen holds a special place in the oeuvre and life of Isaac Israels. Even in the years when Israels lived abroad, he would still return to The Hague and Scheveningen in the summer to work there. Women - both working class and elegant ladies - fascinated the artist throughout his career and form a recurring theme within his oeuvre. The present lot is a powerful and joyous rendering of two Scheveninger girls. The artist has no need for the trappings of detail. The spectator is drawn in by the pleasant warmth exuded by the girls. The strength of the present lot lies in the wonderful combination of strong sunlight, bright colours and vigorous broad brushstrokes.

0 notes

Photo

An Elegant Lady on a Balcony, Rue de Clignancourt, Paris by Isaac Israëls, 1910

Since 1878, Isaac Israels and his family annually visited Paris for the Salon des Artistes. Here he became well informed with new artistic movements and innovative artists in Paris, such as Emile Zola, Morisot, Redon, Toulouse-Lautrec and others. He succesfully exhibited in Paris from 1882, and during a longer stay in 1889, when he was accompanied by his good friend and writer Frans Erens (1857-1935), he met several of the up-and-coming generation of writers. It is no surprise that, after having lived in Amsterdam, he permanently moved to Paris in 1903, where he lived for the next ten years. One of the reasons of his moving to Paris was Hirsch & Cie, a prestigious couturier based on the Leidseplein in Amsterdam, who had arranged permission for him to go and paint at Paquin's, one of the leading Paris fashion houses. As such, he was no stranger at fashion house Paquin on Rue de la Paix and Décroll on Place de l'Opera, painting mannequins and other scenes within the Parisian fashion industry. He painted Paris and its boulevards from his lofty studio. At first he lived in Hotel Le Peletier in the Rue des Petits Champs, close to the galleries of Durand-Ruel. Around 1907 he repeatedly painted the sloping Rue de Clignancourt at the junction with Boulevard de Rochechouart and the Rue Castiglione, where Isaac stayed at the Hotel Continental. His palette is more "French" then that of his Amsterdam - or Hague oeuvre. Skilful he records the swarming of waggons, carriages, carts and pedestrians in a sunlit Rue de Clignancourt, the passers-by on the Rue de Rivoli and the fashionable young women on the Champs Elysees.

The present lot shows a portrait of a Parisienne wearing a hat on a balcony, which is another recurring theme in his work. These portraits are among the best and most appreciated paintings by Israels. Although he has repeatedly painted from this very balcony, it remains uncertain as to which balcony it was. The present lot was arguably painted on a balcony on Rue Clignancourt, yet the exact location remains unknown. It has also been stated that this painting's location is Rue de Castiglione.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

L'Enfant au poisson by Raoul du Gardier

Raoul Du Gardier painted seductive genre scenes with overwhelming clarity. As often in his works, L'Enfant au Poisson introduces the viewer into a world with a solar coastline and flooded with light, which simply reflects a certain joie de vivre.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

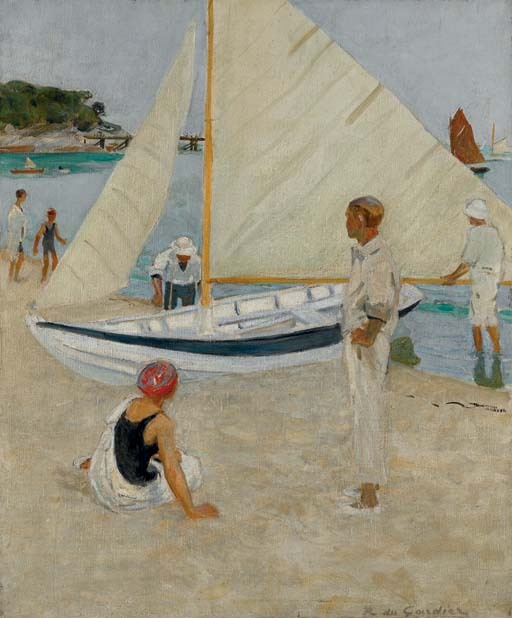

A la plage, Noirmoutiers by Raoul du Gardier

A student of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Raoul Du Gardier had Gustave Moreau as his master. Before being appointed 'painter of the Navy' in 1923, Du Gardier had already made a career as a painter in this genre, participating in the Salon since 1894. He is one of the "traveling painters" who scour the different continents, visiting Africa, Turkey, Madagascar and Réunion. During his travels, he happily performs seductive genre scenes with overwhelming clarity.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Self-Portrait by Alphonse Mucha, 1899

Alfons Maria Mucha (Czech: 24 July 1860 – 14 July 1939), known internationally as Alphonse Mucha, was a Czech painter, illustrator, and graphic artist, living in Paris during the Art Nouveau period, best known for his distinctly stylized and decorative theatrical posters, particularly those of Sarah Bernhardt. He produced illustrations, advertisements, decorative panels, and designs, which became among the best-known images of the period.

In the second part of his career, at the age of 43, he returned to his homeland of Bohemia-Moravia region in Austria and devoted himself to painting a series of twenty monumental canvases known as The Slav Epic, depicting the history of all the Slavic peoples of the world, which he painted between 1912 and 1926. In 1928, on the 10th anniversary of the independence of Czechoslovakia, he presented the series to the Czech nation. He considered it his most important work. It is now on display in Prague.

Alphonse Mucha was born on 24 July 1860 in the small town of Ivančice in southern Moravia, then a province of the Austrian Empire (currently a region of the Czech Republic). His family had a very modest income; his father Ondřej was a court usher, and his mother Amálie was a miller's daughter. Ondřej had six children, all with names starting with A. Alphonse was his first child with Amálie, followed by Anna and Anděla.

Alphonse showed an early talent for drawing; a local merchant impressed by his work provided him with paper for free, though it was considered a luxury. In the preschool period, he drew exclusively with his left hand. He also had a talent for music: he was an alto singer and violin player

After completing volksschule, he wanted to continue with his studies, but his family was not able to fund them, as they were already funding the studies of his three step-siblings] His music teacher sent him to Pavel Křížkovský, choirmaster of St Thomas's Abbey in Brno, to be admitted to the choir and to have his studies funded by the monastery. Křížovský was impressed by his talent, but he was not able to admit and fund him, as he had just admitted another talented young musician, Leoš Janáček.

Křížovský sent him to a choirmaster of the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, who admitted him as a chorister and funded his studies at the gymnasium in Brno, where he received his secondary school education. After his voice broke, he gave up his chorister position, but played as a violinist during masses.

He became devoutly religious, and wrote later, "For me, the notions of painting, going to church, and music are so closely knit that often I cannot decide whether I like church for its music, or music for its place in the mystery which it accompanies." He grew up in an environment of intense Czech nationalism in all the arts, from music to literature and painting. He designed flyers and posters for patriotic rallies.

His singing abilities allowed him to continue his musical education at the Gymnázium Brno in the Moravian capital of Brno, but his true ambition was to become an artist. He found some employment designing theatrical scenery and other decorations. In 1878 he applied without success to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, but was rejected and advised to "find a different career". In 1880, at the age of 19, he traveled to Vienna, the political and cultural capital of the Empire, and found employment as an apprentice scenery painter for a company which made sets for Vienna theaters. While in Vienna, he discovered the museums, churches, palaces and especially theaters, for which he received free tickets from his employer. He also discovered Hans Makart, a very prominent academic painter, who created murals for many of the palaces and government buildings in Vienna, and was a master of portraits and historical paintings in grand format. His style turned Mucha in that artistic direction and influenced his later work. He also began experimenting with photography, which became an important tool in his later work.

To his misfortune, a terrible fire in 1881 destroyed the Ringtheater, the major client of his firm. Later in 1881, almost without funds, he took a train as far north as his money would take him. He arrived in Mikulov in southern Moravia, and began making portraits, decorative art and lettering for tombstones. His work was appreciated, and he was commissioned by Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, a local landlord and nobleman, to paint a series of murals for his residence at Emmahof Castle, and then at his ancestral home in the Tyrol, Gandegg Castle. The paintings at Emmahof were destroyed by fire in 1948, but his early versions in small format exist (now on display at the museum in Brno). He showed his skill at mythological themes, the female form, and lush vegetal decoration. Belasi, who was also an amateur painter, took Mucha on expeditions to see art in Venice, Florence and Milan, and introduced him to many artists, including the famous Bavarian romantic painter, Wilhelm Kray, who lived in Munich.

Count Belasi decided to bring Mucha to Munich for formal training, and paid his tuition fees and living expenses at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. He moved there in September 1885. It is not clear how Mucha actually studied at the Munich Academy; there is no record of his being enrolled as a student there. However, he did become friends with a number of notable Slavic artists there, including the Czechs Karel Vítězslav Mašek and Ludek Marold and the Russian Leonid Pasternak, father of the famous poet and novelist Boris Pasternak. He founded a Czech students' club, and contributed political illustrations to nationalist publications in Prague. In 1886 he received a notable commission for a painting of the Czech patron saints Cyril and Methodius, from a group of Czech emigrants, including some of his relatives, who had founded a Roman Catholic church in the town of Pisek, North Dakota. He was very happy with the artistic environment of Munich: he wrote to friends, "Here I am in my new element, painting. I cross all sorts of currents, but without effort, and even with joy. Here, for the first time, I can find the objectives to reach which used to seem inaccessible." However, he found he could not remain forever in Munich; the Bavarian authorities imposed increasing restrictions upon foreign students and residents. Count Belasi suggested that he travel either to Rome or to Paris. With Belasi's financial support, he decided in 1887 to move to Paris.

Mucha moved to Paris in 1888 where he enrolled in the Académie Julian[18] and the following year, 1889, Académie Colarossi. The two schools taught a wide variety of different styles. His first professors at the Academie Julien were Jules Lefebvre who specialized in female nudes and allegorical paintings, and Jean-Paul Laurens, whose specialties were historical and religious paintings in a realistic and dramatic style. At the end of 1889, as he approached the age of thirty, his patron, Count Belasi, decided that Mucha had received enough education and ended his subsidies.

When he arrived in Paris, Mucha found shelter with the help of the large Slavic community. He lived in a boarding house called the Crémerie at 13 rue de la Grande Chaumière, whose owner, Charlotte Caron, was famous for sheltering struggling artists; when needed she accepted paintings or drawings in place of rent. Mucha decided to follow the path of another Czech painter he knew from Munich, Ludek Marold, who had made a successful career as an illustrator for magazines. In 1890 and 1891, he began providing illustrations for the weekly magazine La Vie populaire, which published novels in weekly segments. His illustration for a novel by Guy de Maupassant, called The Useless Beauty, was on the cover of 22 May 1890 edition. He also made illustrations for Le Petit Français Illustré, which published stories for young people in both magazine and book form. For this magazine he provided dramatic scenes of battles and other historic events, including a cover illustration of a scene from the Franco-Prussian War which was on 23 January 1892 edition.

His illustrations began to give him a regular income. He was able to buy a harmonium to continue his musical interests, and his first camera, which used glass-plate negatives. He took pictures of himself and his friends, and also regularly used it to compose his drawings. He became friends with Paul Gauguin, and shared a studio with him for a time when Gauguin returned from Tahiti in the summer of 1893. In late autumn 1894 he also became friends with the playwright August Strindberg, with whom he had a common interest in philosophy and mysticism.

His magazine illustrations led to book illustration; he was commissioned to provide illustrations for Scenes and Episodes of German History by historian Charles Seignobos. Four of his illustrations, including one depicting the death of Frederic Barbarossa, were chosen for display at the 1894 Paris Salon of Artists. He received a medal of honor, his first official recognition.

Mucha added another important client in the early 1890s; the Central Library of Fine Arts, which specialized in the publication of books about art, architecture and the decorative arts. It later launched a new magazine in 1897 called Art et Decoration, which played an early and important role in publicizing the Art Nouveau style. He continued to publish illustrations for his other clients, including illustrating a children's book of poetry by Eugène Manuel, and illustrations for a magazine of the theater arts, called La Costume au théâtre.

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Girl with a Plate with a Folk Motif by Alphonse Mucha, 1920

Born in Ivancice in what is now Czechia, Alphonse Mucha began his artistic training in Prague and Munich before moving to Paris to enroll in the Académie Julien in 1888. Mucha is best remembered for the prominent role he played in shaping the aesthetics of French Art Nouveau at the turn of the century. In December of 1894, while the artist was at Lemercier’s printing workshop doing a favor for a friend, a call came in from Sarah Bernhardt, the greatest actress of her generation, who urgently needed a poster designed for her next performance. With the regular Lemercier artists on holiday, the printer turned to Mucha in desperation. It was a moment of happenstance that would change the artist’s life. While he had been working in relative obscurity for several years, Mucha’s poster for Berhardt’s production of Gismonda rocketed the artist to near-immediate fame. Though the printer was hesitant about Mucha's design because of its new, unconventional style, ‘La divine Sarah’ loved the image and the public followed suit. The posters immediately became collector’s items, and collectors went so far as to bribe bill posters and cut the posters down under cover of night in order to obtain them.

As a result, Le style Mucha, as Art Nouveau was known in its earliest days, was born. The success of the Gismonda poster resulted in a six-year contract between Bernhardt and Mucha, and the artist designed not only posters for her performances, but costumes and stage decorations as well. It was in the artist’s iconic images of Bernhardt that he also began to experiment with what would come to be one of the hallmarks of his later work – having his model directly engage the viewer’s gaze. This same powerful gaze is on full display in the present painting, as the beautiful young artist holds up the plate she has decorated with an Eastern European floral design while fixing the viewer with her piercing stare.

Girl with a Plate with a Folk Motif is typical of the direction of Mucha’s art after 1910, when he and his family returned to Prague and he was working on The Slav Epic, a series of 20 paintings depicting the history of the Czech lands and other Slavic countries which comprise his late masterpiece. As Mucha moved away from commercial work in the second half of his career to focus on patriotic history painting, he traveled through Russia and Poland to the Balkans, making sketches and taking photographs to document what he saw. As a result, Slavic costume, themes, and decorative elements became increasingly common in his work from this period outside of The Slav Epic as well. The luminous, fluid brushwork and the harmonious cool pastel color palette found in the present work are also hallmarks of Mucha’s late work. The sinuous line of Mucha’s Art Nouveau style is still evident in the sitter’s hair and in the folds of her voluminous garment, but it has been suffused through a symbolist bent – the delicate strokes of purple and blue which define the edges of the figure make her seem as if she is glowing, giving her an almost mystical quality.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Crack Shot by James Tissot, 1869

An elegant and fashionably dressed young woman, aiming a gun, stands in a walled garden before a table loaded with pistols and rifles. The title of this painting, The Crack Shot, reveals everything the viewer needs to know, but the subject of a markswoman would have been unexpected and potentially alluring. The French artist James Tissot (1836–1902) developed a highly successful career in London, and this portrait is one of his greatest achievements. It dates from 1869, when Tissot was on his second visit to the capital. He settled in England shortly afterwards, becoming part of a society circle that included Edward, Prince of Wales (1841–1910).

The identity of the poised and determined woman in this painting is unknown, but the bearded man seated behind her may be the artist’s friend Thomas Gibson Bowles (1842– 1922), founder of the then satirical journal Vanity Fair. Tissot mainly painted images of glamorous society men and women, and he was particularly attentive to the fall of fabric and decorative trimmings of dress, perhaps because his family were involved in the linen and millinery trade.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Les Adieux, The Farewells by James Tissot, 1871

This is one of the first works James Tissot painted after his arrival in London in 1871, and one of several in which he treated the theme of parting. It has been suggested that such subjects were provoked by Tissot's sudden departure from his native Paris and his sense of displacement in London, although clearly he was also responding to the English taste for narrative. The reluctantly parting couple are divided by a fence that symbolises their imminent separation. The scissors which dangle from the lady's waist also allude to their division. The image became famous through an engraving published in 1873.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Tale by James Jacques Joseph Tissot, ca. 1878-1880

Henry James commented that his two favorite words in the English language were ‘summer afternoon.’ This delightful picture of Tissot’s partner and muse, Kathleen Newton, reading in the garden of their house in Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, exemplifies the quiet happiness he found with her there, and celebrates the joy of childhood and family life. It exudes the contentment and ease found on a summer afternoon in the garden, surrounded by loved ones.

A noted anglophile, Tissot had come to London from his native France in 1871 following the fall of the Paris Commune after the Franco Prussian war. An astute businessman, he had established a reputation on both sides of the Channel prior to the calamity, and was encouraged in his move by Thomas Gibson Bowles, founder of Vanity Fair magazine, for whom he supplied political cartoons. London offered Tissot a safe haven from the horrors of Paris at the time and better immediate prospects for art sales. He soon found a ready market for historical dress and modern-life pictures and earned enough in a year to buy a villa in the north-London suburb popular with artists, St. John’s Wood, at 17 (now 44) Grove End Road. According to the diarist de Goncourt, Tissot’s home was both elegant and welcoming – champagne was always on ice for visitors, and he joked that a footman was employed to polish leaves in the shrubbery. The villa had large gardens, with trees and ponds at front and back. Tissot had the pond in the back garden extended and formalized. Its stone coving can be glimpsed in the distance of The Tale, with surrounding plants including ‘giant rhubarb’ (gunnera) on the left. The pool’s colonnade, familiar from many other of Tissot’s London paintings, is hidden here by the chestnut leaves framing his sitters.

Over the course of his time in London, Tissot’s art changed direction from the genre scenes with which he had gained fame, both as a result of having his work rejected from the Royal Academy in 1875 and through his meeting the beguiling Kathleen Newton, one of the two subjects of the present work, in 1876. Born Kathleen Kelly in Agra, where her father was a clerk in the Honourable East India Company’s Civil Service, Kathleen would lead a remarkable life notable for its brevity, modernity and defiance of convention. After the Indian Rebellion she was sent to England for safety and schooling. At the age of 16 she travelled back to India for an arranged marriage to Dr. Isaac Newton, a distinguished army surgeon. On the voyage she met and fell in love with a Captain Palliser, whom Dr. Newton cited in divorce proceedings after Kathleen ran away to join Palliser and became pregnant. She returned to England for the birth of her daughter, and a son, probably also fathered by Palliser, was born before Kathleen met Tissot. The artist’s first certain portrayal of her is the etched Portrait of Mrs. N., made in autumn/winter 1876. Though his Catholicism prevented him from marrying a divorcée, sometime in 1877 she came to live with Tissot, the pair cohabiting as man and wife until her death from tuberculosis in November 1882.

Captured sitting beneath the chestnut tree, in an intimate ‘snapshot’ image, Kathleen reads to her sister’s daughter Lilian Hervey, known as Lily, who lived only a few minutes’ walk from Tissot’s home. Kathleen is reading a story aloud, her lips slightly parted and fingers about to turn a page, and Lily is listening intently. Kathleen’s two children lived with the Herveys, sharing a nanny, and all the children visited Tissot’s house from time to time for walks, musical interludes, play, and picnics in the garden. Tissot made sketches and photographs of Kathleen and the children, which served as source material for paintings and etchings from 1878 to 1882. Lily was especially attached to her aunt and seems to have been a willing sitter too, as she appears on the same fur-covered bench in two pictures both entitled Quiet (c. 1881), the larger of which was exhibited by Tissot at the Royal Academy in 1882. The other is an upright version of the present composition measuring 12 ½ x 8 ½ in., sold at Christie’s on 5 November 1993, lot 159 (now in The Lloyd Webber Collection), but it instead depicts Lily cheekily turned towards the artist, distracted from her story, and peering over the garden bench. The present picture is a more tranquil and satisfying composition, with the sun-filled lawn, distant pond and dappled light filtering through the leaves of the chestnut tree.

Since the rejection of some of Tissot’s submissions to the Royal Academy in 1875, he had changed marketing tactics and showed more paintings outside London, where there was considerable demand from provincial dealers and new municipal galleries. Small paintings and prints were more easily accommodated and sold, as well as being more transportable. Such was the case with The Tale, exhibited in Birmingham and Liverpool in 1880 and 1882 respectively. When it was exhibited in Birmingham, The Tale was described by the Birmingham Daily Post’s art critic as ‘a work of very high merit. It is a tiny canvas, but there is breadth of treatment in it.’ In fact, the painting is on a thin mahogany panel, a support that Tissot favored for his small London-made pictures. Onto a lead-white ground that gave luminosity (and was used for this reason by both Impressionist and Pre-Raphaelite painters), Tissot laid broad diagonal brushstrokes of warm brown to create mid-tones and to animate the surface. This under-layer can be seen in places, especially beneath the lawn. Tissot’s use of vivid colors for the grass and leaves is radically modern: he mixed brilliant Emerald and Viridian Green with dazzling Barium Chromate and Strontium Yellow, poisonous paints that Vincent van Gogh also liked for their striking freshness. They certainly helped Tissot’s pictures stand out from the dense crowd of other works on gallery walls. Alongside this modernism, Tissot’s technique was grounded in tradition. His stunning fluency with the brush enabled him to capture glints of sunlight on hair and clothes, details of ribbons and folds, Kathleen Newton’s earring, and the delicate profiles of young woman and child. It is such eloquent and beautiful detail that made, and continues to make, Tissot’s work so attractive to viewers and collectors.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An Orange Garden by John William Waterhouse

The present lot is a heretofore-unlocated canvas from a small group of picturesque, lushly colored genre scenes that J. W. Waterhouse painted, or at least conceived, in Capri during the late 1880s. This Italian island had become increasingly popular with artists from around the world for its beautiful scenery, sunny climate, and abundant models. Having been born in Rome, 'Nino' Waterhouse may even have been able to converse with the locals in Italian.

An Orange Garden depicts three models picking and gathering oranges, a continuation of the traditional view that women enjoy a particularly harmonious relationship with nature, and also a portent of the maidens-stretching-to-pick-flowers theme that Waterhouse would explore for the rest of his life. This composition showcases the artist’s lively brushwork and many hallmarks of his style, such as the stone staircase that connects the scene’s upper and lower halves, the subtle pink dress and the rich mauve headscarf that move our eye along that staircase, the trees’ twisting trunks and branches, the flowers planted in terracotta pots, the weathered surfaces of the stucco architecture, and the deft juxtaposition of whites and off-whites best admired in the youngest girl’s apron.

With this and the other Capri scenes, Waterhouse created a Mediterranean variation on the popular paintings of his fellow Englishman George Clausen (see lot 23), the disciple of Jules Bastien-Lepage who had sweetened that late French master’s frank views of working peasant children to suit the tastes of British collectors. Waterhouse’s London dealer, Agnew’s, received An Orange Garden on 1 February 1890 and sold it just 19 days later to Dr. Alfred Palmer JP, a member of the family that owned the Reading-based bakers Huntley & Palmer. Around the same time, Palmer’s Berkshire neighbor, the financier Alexander Henderson, acquired from Agnew’s the larger Orange Gatherers and went on to become Waterhouse’s most significant patron.

The reappearance of An Orange Garden is a welcome reminder of how skillfully Waterhouse could transform a seemingly ordinary, non-narrative scene of modern life into a lyrical vision of color and light.

5 notes

·

View notes