Text

Original painting for the TV Guide cover of the Apollo-Soyuz Mission coverage, July 12-18 1975 by John Berkeley. Interestingly, in the preliminary draft, the positions of the cosmonaut and astronaut were reversed.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

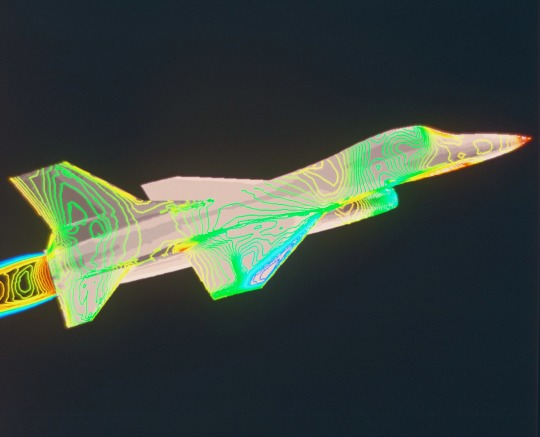

Computational Fluid Dynamics flow field grid of an F-16A, NASA Ames Research Center 1988

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

do y'all think the people who worked on gemini 9 ever called it geminine

#they pronounced gemini weird like ''gemin-knee'' which makes the words mix less well#i hate that pronunciation of gemini btw even if it is official uughughugh

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

PREVIOUSLY UNSEEN GEOLOGY TRAINING PHOTOS????

(top pic - Hawaii, 1967 - bottom pic- Alaska, 1966)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

One of the weirdest Apollo-era training devices I’ve seen, the OMEGA (One-Man Extravehicular Gimbal Arrangement). This was apparently used alongside underwater training to simulate zero g, especially for maneuvers that required more quick responses. (Source).

#apollo program#astronaut training#i must also note that the person using this is wearing like a flight suit and then just regular socks and loafers#tbh seems like just wearing regular shoes with the whole jumpsuit during training is more common than i thought lmao#(flashbacks to the photo of mike collins in loafers)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

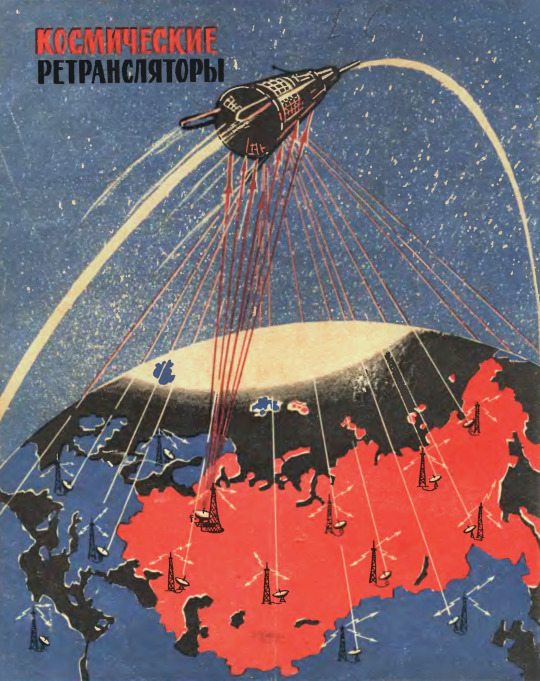

Illustration from РАДИО (Radio) magazine, 1962 issue no 8. The text says something like “space repeaters,” I think in relation to radio relays. The orbiting object resembles Sputnik-3, launched in 1958. The specific radio tower by Moscow on the map is the Shukhov tower.

#I just found out about this RADIO magazine and let me tell you the illustrations in it from the 50s and 60s slap#soviet union#Soviet Space Program#ussr#satellite#sputnik 3#illustration

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jupiter in Five Filters

by Judy Schmidt

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok nevermind, I found it, I guess it was C. C. Williams? But here is the list of specializations all in one place if anyone’s interested:

Group 2: New Nine

Neil Armstrong: trainers and simulators

Frank Borman: Boosters, with special responsibility for abort systems

Pete Conrad: Cockpit layout, pilot controls and systems integration (lmao @ them giving one of the shortest guys the job of designing the cockpit)

Jim Lovell: recovery systems, including the parachutes, paraglider and lunar module

Jim McDivitt: Guidance and navigation systems

Elliot See: electrical systems and coordination of mission planning

Tom Stafford: Communications systems, mission control, and the ground support network

Ed White: Flight control systems

John Young: Environmental control systems, survival gear, personal equipment and space suits

Group 3: The Fourteen

Buzz Aldrin: mission planning (lol why did they not give him rendezvous...)

Bill Anders: environment controls

Charlie Bassett: training and simulators

Al Bean: recovery systems

Gene Cernan: spacecraft propulsion and the Agena

Roger Chaffee: communications

Mike Collins: pressure suits and extravehicular activity

Walt Cunningham: non-flight experiments

Don Eisele: attitude controls

Ted Freeman: boosters

Dick Gordon: cockpit controls

Rusty Schweickart: in-flight experiments

Dave Scott: guidance and navigation

C. C. Williams: range operations and crew safety

Does anyone know what all the assigned specializations of the Gemini astronauts were? Like, the New Nine and the the 3rd astronaut group all got assigned fields of specialization (for example, Collins: EVA, Young: space suits, Borman: booster rockets). I could have sworn someone was assigned general astronaut safety stuff, but I can’t find who it was?

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone know what all the assigned specializations of the Gemini astronauts were? Like, the New Nine and the the 3rd astronaut group all got assigned fields of specialization (for example, Collins: EVA, Young: space suits, Borman: booster rockets). I could have sworn someone was assigned general astronaut safety stuff, but I can’t find who it was?

#please help me out here guys lmao#I could just be mixing this up with all of john young's safety notes but I feel like this was a separate thing#nasa#project gemini

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cosmonaut Andriyan Nikolayev. Photo by S. Baranov (1960s).

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood (Richard Linklater, 2022).

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

[04/10/1957] — Бип...бип...бип...

History changed on October 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union successfully launched Sputnik 1, the world's first artificial satellite.

It was around the size of a beach ball, weighed 83.6 kg (183.9 pounds), and took about 98 minutes to orbit Earth on its elliptical path. This ushered in a new age of political, military, technological, and scientific developments, and although the Sputnik launch was a single event, it marked the start of the space age and the U.S.-U.S.S.R space race.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

People rightly get emotional about the perceived humanity of the Mars rovers but I just have to go off for a moment about the Soviet Venera program of the 60s-80s and how it gets me feeling just as emotional.

I think part of the appeal of the Mars rovers is their longevity—they have stuck around far longer than their projected lifespans, occasionally performing little rituals that reinforce the connection between these robots and their human parents (eg. the “happy birthday” song).

In contrast, the final and most sophisticated Venera landers lasted barely 2 hours on the surface of Venus. Why? Venus is a fucking hellscape that’s like 850°F (454°C) on the surface, with an atmospheric pressure 95 times higher than Earth’s, cloaked in corrosive clouds. Despite these insane conditions, Soviet scientists and engineers sent 16 spacecraft to Venus.

They failed a lot. The first two probes didn’t even get there. Venera 3 made it all the way. On board it carried a variety of scientific sensors, and a set of Soviet medallions. It impacted the surface in March 1966, but its instruments failed long before it could send back anything relevant. It was pulverized by the pressure and melted down into slag by the heat.

A year later, a reinforced Venera 4 managed to send back the atmospheric data its sibling hadn’t been able to capture. It was the first spacecraft to take these measurements on another planet. As it descended down into the hell that it was analyzing (91°F...200°F...oh...346°F... 504°F...oh god), the probe cracked open at the top and was crushed before reaching the surface. Like an egg. Like a skull.

Due to the data it sent back, the mission was considered a success, but its engineers had actually hoped that it would have been able to endure and make a soft landing. They had designed it to survive even in the unlikely event that it landed in water, and had equipped it with a battery that would last up to 100 minutes. Initially did not want to accept that it had not reached the surface intact.

In 1970, Venera 7 was the first probe to succeed in landing, but not without its own struggles. Things were going well until just before touchdown, when its parachute failed. The probe hit harder than expected, but it was so incredibly overbuilt that this time its titanium skull did not crack, merely toppling over onto its side and throwing its transmitter out of alignment. It was presumed dead, but, as scientists would only realize weeks later, it fought on for another 23 minutes, transmitting a faint stream of data back to its home millions of miles away before succumbing to the temperature and pressure.

Into the 80s, the Soviet Union landed 6 more spacecraft on the surface of Venus. They took color photographs (the first from another planet), recorded sound, and analyzed the soil. They allowed us to pull back Venus’s poisonous veil and see something we were not designed to see. These later landers were rated to last only 30 minutes on the surface, but they generally doubled or tripled that time. Under stifling heat, toxic air, and immense pressure, they gave their best until they ultimately boiled away.

If Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids, Venus is worse. The Mars rovers are like children you can watch grow up and slowly become more distant with age. The Venera probes/landers were children that their Soviet parents poured their time and energy and love into all the while knowing that they were going to be consumed in a blaze of glory turned miserable death. That their useful lifespans would be measured in mere minutes.

Maybe this is just me ascribing feelings that weren’t there to the engineers and anthropomorphizing the robots too much, I’m no scientist, but emotionally that is gut wrenching. When I first learned about these missions I cried. And not only because I feel for the spacecraft. This is also a story about a nation and culture that no longer physically exists (paralleling the landers themselves). Throwing a bunch of progressively more overbuilt stuff at a seemingly crazy task is one of the most stereotypically Soviet things I can think of. All of the Venera missions carried special medallions engraved with Soviet imagery and made out of titanium so as to withstand the Veniusian environment. On some other planet, possibly the only evidence of human existence is a bunch of melted metal and possibly a few representations of something that no longer exists, something that a lot of people at the time believed in, that held their hopes and dreams—that is haunting. To me the Venera program encapsulates a lot of the same elements of unexpected humanity as the saga of the Mars rovers, but is more tragic because it has a different level of temporality.

#feeling emotional about some hunks of metal again tonight lads#long post#sorry about that#I only meant for this to be like 1 paragraph and then realized I couldn't fit in it all in to just that#also like even if you hate the soviet union I think we can agree there is something to this#like on a human sociological level#venera#venera program#ussr#venus#mars#Soviet Space Program

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky museum in Izhevskoye village (his birthplace). Photo by M. Savin (1982).

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saw this license plate today and I'm still ugly laughing about it

174K notes

·

View notes