Text

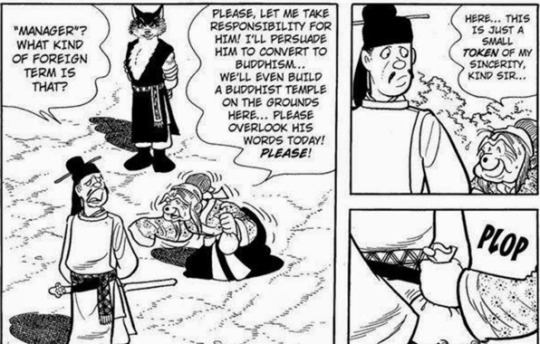

I like this screenshot because it shows how complex of a character Prince Oama is. His reason for worshipping the Sun God is justified, but I think this was point where I could see the seeds of religious abuse being planted by Oama.

Phoenix Volume 11

This story (volume 10 & 11) is by far my favorite part of the Phoenix series. While there were still the ideas of immortality and reincarnation. This volume specifically allowed us to understand the ideas that were being developed within the previous volume. This volume focused primarily on the effects religion had on society. Within this volume we see how religion can affect politics and society. But no only this the story was able to wrap it up as a part of Japanese history.

One thing that stood out to me was the juxtaposition of the characters within the two different storylines. In both story we get a human character with the head of a dog, fighting the ruling system in their society. We also see the juxtaposition between Saruta and the emperor’s uncle. Both started off with righteous ideals and ambitiously pursued these goals, but when they arrived to a position of power, they immediately begin acting the same way as their predecessors. I feel like this did no only display the cyclical nature we’ve seen throughout all of Phoenix but it also displayed how negative the role of religion is in society, and the effect it has on leaders.

This story to me felt as one of the most impactful ones in the series. It’s also unfortunate that Tezuka didn’t have a chance to finish this series because with every volume we could see some kind of connection with other volumes and the overall picture was becoming more and more clear to us. But either way, this volume proved to be a fitting closing chapter for Phoenix.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It also confused me when Suguru suddenly grew a wolf head and when he lived the explosion. I think that this is due to the fantastical nature of story where anything can happen. It makes for a happy ending. :)

Phoenix 11

I was a bit confused by the switch of the wolf head toward the end of the volume. It seemed to come largely out of nowhere, with only a bit of fur on the back as foreshadowing. I guess it gave a better ending where the spirit could be with Inugami even when he turned back into a human at the end of the story in the past. I just could not get into that sudden shift and how quickly everything returned largely to normal with Inugami. Perhaps it was because there were larger political changes that turned the eyes of most people away from Inugami.

It felt good to see that Tezuka took on his old style of criticizing old Japanese texts when referring to the Nihon Shoki. It felt just like his criticism of the Kojiki from volume one and the crying Buddha from volume three. But interestingly, the character Inugami did not come from Japan. The local spirits were championing a foreigner, making the divide of foreign Buddhist gods and the local guardians appear the incorrect paradigm. The clash was not primarily of gods. It was one of men. The story began with violence between different people even before the issue of encroaching Buddhism became central to the plot, and the uprising that Inugami asked for ended with bloodshed the establishment of yet another religious order.

Overall, this volume really takes on the idea that history just repeats itself with the abuse of religion. One religion gets taken down, and another springs up to take its place. It was never about the content of the religion itself, however. Religion takes hold in politics in a manner that is almost completely arbitary. Buddhism was chosen to be control others. So was the succeeding choice of worshiping the sun god. The Church of Light seemed to come out of nowhere, having little development and using cult-like and autocratic methods to keep its adherents. Its successor, the Church of Eternalism seemed to come from equally corrupt roots.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phoenix Vol. 11

Sun Part 2

A fitting finale to arguably Tezuka’s most complete and compelling story, the second part of Sun is a rollercoaster of impactful characters, engaging storytelling, and important themes. He masterfully blends a well-written and emotional story with his themes of humanism, religion, and reincarnation, which actually makes it harder to discuss these individual moments (but I’ll try).

Tezuka’s sense of imagination is boundless. The future underwater base where they eat plankton and wear animal helmets is bizarre, which I assume was the intended reaction, and the various characters and spirits of the past are also quite imaginative. Of course, Tezuka manages to fit in some self-aware humor as well.

The plot is bold and well-paced. The characters are convincing and multi-dimensional. I was heartbroken after Princess Tochi’s death because I sympathized with her situation (after cuddling with Inugami). I admire characters like Iki no Fubito Karakuni, who is devoted to the capital yet understanding and reasonable (honorable mentions: Prince Oama, Inugami/Suguri, Prince Otomo). I’ve previously separated Suguri from Inugami personality-wise but now realize the obvious similarities between them; they’re both passionate and prideful about their beliefs and what they think is right. They both kill a significant amount of people, which interestingly affords them no karmic retribution, however they do so in service of the cause that they believe in. I initially thought the love between Suguri and Yodomi was forced since it happened so fast, but I was gladly proven wrong. The future part of Sun may not be as complex and interesting as the past, but it still showcases amazing character development and incredible plot moments. I did not expect Suguri to turn into a wolf or live the explosion, but I guess it’s because of fate or something. I also found the ending very satisfying. In the past, I liked the connection to Strange Beings with the reference to Happyaku Bikuni.

There’s plenty of parallelism throughout the story. Most of the actions that Suguri and Inugami are reflections of one another (wolf head, self-sacrifice, attaining peace at the end). There’s also a parallel between the death of Princess Tochi and Yurika since they both loved “bad guys” who immediately regretted killing their lovers. There’s the obvious parallel of using religion as a weapon of power, but also between Oama and Saruta, who both lead a revolution against abusing religion, but hypocritically abuse religion when in power (although Oama has just intention at first). This parallelism ties into the theme of karma and reincarnation and how everything that happens has happened before in some way.

The themes remain the same as in the previous volume for the most part. Inugami and Suguri are blatant manifestations of Tezuka’s humanist mantra. The Church of Light is overtly hypocritical, criticizing “materialism” and claiming to be the absolute truth while killing non-believers, brainwashing people, and using duels to control prisoners. In both the past and future, religion is used as a vehicle for power, however the phoenix reveals something new about it.

The phoenix tells Inugami that “all faiths and religions are ultimately correct” and they’re only bad when associated with attaining (and taking advantage of) power. Sun is noticeable more forthright than previous chapters when it comes to depicting spiritual beings, however, the phoenix implies that it doesn’t matter. Whether you attribute natural occurrences to religion or not, you should have the freedom to believe it.

Some interesting quotes and panels, mostly featuring Prince Oama:

“…Perhaps that’s what people mean when they talk about faith…that each person has to be able to sense his or her own god…” - Oama

“I, too, am like a cornered wolf, who must finally show his fangs…” - Oama

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I completely agree! I loved the characters, and Inugami is probably my favorite protagonist yet (he reminds me of Ashitaka from Princess Mononoke). Although the plot is lengthy and takes many different turns, it’s all connected and worthwhile to read because of characters, themes, and compelling storytelling.

Phoenix Vol.10/Continental Impact

The reading of Continental Impact sets up the circumstances and background for the part of the story occurring in the past. It shows the relevance of the religious divide in the story and the history behind it. This allows us to understand the plot of the story of Inugami. Once again we see Tezuka criticizing Buddhism or religion in general and the legitimacy of the emperor. We also see him bring up the use of religion to oppress people again throughout the story.

Overall, this story was one of the better ones, and I believed it was his most well written one yet. The story is easy to follow, there is not an overabundance of characters, and every character introduced actually plays a role in the development of the plot. The characters in these stories also had some unique designs making it even more enjoyable. I think the portrayal of the buddhist gods in this volume were a little biased, showing that these gods where all evil and greedy and did not care about the peace of the people. The way the stories are intertwined with each other is also very interesting, it’s hard to see where the story is heading and I like that as a reader.

After reading this volume, I’ve realized the Phoenix is become less and less important as the volumes go by. At first the Phoenix was this all mighty being that was unable to catch and refused to give it’s blood to anybody and most of the stories revolved around the phoenix. However in these recent volumes anybody can get their hands on the phoenix and the phoenix makes less and less appearances. Also something that stood out to me was a common theme within both stories where people are using religion as a way to oppress others. The way the stories are developing really have me excited to see what happens in volume 11.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The main takeaway that I got from this volume is the duality of human nature and of the universe. This could explain why Tezuka portrayed the Buddhist spirits as malevolent beings: to show that there’s another side to the history of a peaceful religion like Buddhism.

Phoenix Volume 10/Continental Impact

Continental Impact

This felt slightly like a more detailed version of what I covered in AP World History about Japan and its relationship with China. However, I was surprised to see how the manga strays away from history, as Tezuka doesn’t show any assimilation of Shinto culture into the newly integrated Buddhism. It’s depicted here as Buddhism being a vital part of being Japanese, as not practicing the religion meant directly disobeying the emperor. It also makes sense how deeply Chinese culture is integrated into Japan, as kanji is Chinese characters, but I was surprised to find out that the Kojiki is a mixture of Chinese and Japanese.

Volume 10

This volume had one of the most engaging plots yet and Tezuka really shines with his storytelling this time around, as I eagerly await to find out what happens in volume 11. I love the juxtaposition of past and future being connected with similar issues, as the shadow people are oppressed for not believing that the leader who drank the Phoenix’s blood isn’t a god and the Shinto spirits and believers are oppressed for not following the emperor’s belief in Buddhism. This shows that no matter the time period, religion is used to gain power and by proxy oppress others. I’m also surprised how tolerant the royal officials are when talking to a man with a wolf head, as I expected them to instantly yell demon and kill him on the spot. It shows that kindness can go along way and make any monster a hero.

I enjoyed how the Shinto spirits were handled as only wanting peace, but I feel like the depiction of the Buddhist spirit warriors was inaccurate. If Buddhism is all about the practice of peace and finding enlightenment by treating the world with respect, why would these fire-breathing warriors try to murder other peaceful spirits? Tezuka depicts the new religion as invasive and harmful to Japan. This may be used to symbolize that Japan should be wary of foreigners as they bring cursed ideas and might be alluding to the U.S. entering Japan during WWII.,but it’s difficult to tell.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continental Impact / Phoenix Vol. 10

Schirokauer: Continental Impact

This is a short piece that covers the late Yamato and Nara periods. It seems that Japan has borrowed many aspects of Chinese culture, such as government, language, and religion, particularly Buddhism. Japanese rulers and aristocrats have also used Buddhism to legitimate their power as divine. This ironically turns a peaceful religion into one of power, and this is reflected in various Phoenix volumes such as Karma.

Sun Part 1

This volume is one of my favorite volumes so far in the series. Striding the line between spirituality/religion and realism as well as nature and humanity, this is a powerful, creative, and complex story. I feel like almost all of the characters are three-dimensional and affect the story in significant ways. The protagonist of the past, Harima/Kuchi’inu/Inugami, is a noble, moral, and thoroughly likeable character, while Suguru is somewhat likeable but is mostly driven by anger. I loved the transitions between the past and future throughout and the interesting approach to storytelling (gradual revelation). There’s also noticeably a lot of gore in this one: little girls being roasted, faces being torn off, bloody wolf bites, etc. Although it’s violent, Tezuka knows when to throw in some humor.

This is an obvious commentary on religion, specifically Buddhism, and how the nobility exploit it to obtain power. Characters are obsessed with religious or spiritual divinations, which determine who they kill (however, of course, they’re still human and accept bribes, as shown below) or their own fate. On the other side of the coin, there’s the old woman, who’s deeply spiritual and predicts the future multiple times, and there’s the spirit creatures, the wolves who used to coexist with humans and the spiritual manifestations of Buddhist deities. I’m not sure, but I think Tezuka wants the reader to believe exactly that: there are two sides to every coin, and this theme of duality permeates on macro and micro levels.

The future part of Sun has not yet blossomed, but I do like the story and characters so far. There is no tyrannical ruling body, but there is a “Church of Light” with a figurehead who uses religion to attain power (like from the past) and classist ideologies with the separation between “light” and “shadow” people. We also see an appearance from Saruta finally, as well as the most significant mention of the phoenix in the volume. Although I have a lot of questions, I’m very satisfied with this volume.

0 notes

Text

I also found it odd that Sakon Suke is eternally condemned for allowing her murderous and tyrannical father to be killed, but I think that the phoenix isn’t necessarily trying to punish her. She learns a lot and is grateful for her role as a healer and, although her life is abruptly ended by her “suicide”, she enjoyed her life while it lasted, which is a frequent mantra throughout the series.

Phoenix Vol 9

Overall the stories presented throughout the volume where very interesting. In a way these stories presented some recurring themes throughout the phoenix, such as immortality, and karmic retribution but through some new perspectives. Not only this, but these stories also tackle some key problems in human society through the use of things such as the clones presented in the second half of the chapter.

The first story in the volume provided a different perspective on the recurring themes of this manga. The nun experiences a form of immortality through the endless time loop she is put in. As punishment for killing herself in an attempt to kill her father, the phoenix puts her in a time loop where she repeats the events of her life over in over again in 30 year intervals. This seems extremely similar to the story of the space pilot that fell into a similar situation after murdering a civilization of bird people. Essentially, these two stories provided these themes in the same way. However, in both stories we see characters that do things that deserve more punishment than the protagonist but the phoenix fails to punish them. For example in this story the nun’s father murdered droves of people for selfish reasons, and the phoenix didn’t even bat an eye at it yet the nun who killed one person for a way more reasonable reason is forced into this time loop. Essentially, this is another story where we see the phoenix use immortality as a form of punishment.

The second story also provides a different perspective on some of the recurring themes of phoenix. In this story immortality can basically be achieved through cloning. However, the main focus of this story is how society treats groups of people they decide are not human. This story to me is extremely similar to the story of the Robitas. In both stories we see the struggles of a group that feels like they are humans and should be treated as such even though society fails to recognize them as such and both stories show that the Robitas and the clones, came to the conclusion of just killing themselves. Both stories are very interesting, but i can’t help to see them as copies of previous stories in the phoenix.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I also loved both of the chapters! Both of them explored the idea of treating all life with equal importance, which is explored in many Phoenix volumes but especially Karma. In Strange Beings, the living beings in question were the demons and supernatural creatures, and in Life, it was the clones.

Phoenix 9 : Strange Beings + Life

I thought this volume was particularly interesting, and I really enjoyed both stories that were a part of it. Two of the most important themes that we’ve seen throughout Tezuka’s work so far are the idea of cyclical time and the exploration of what constitutes a human, and I thought it was interesting that each story went further in depth into one of these topics.

Strange Beings is probably Tezuka’s most explicit use of cyclical time. Although it’s been shown in many other cases, this story involves a literal loop with a fixed period of time within it. This whole story feels like a microcosm of the larger reality in Phoenix, where humanity is doomed to repeat its mistakes for eternity. Even though Sakon Suke does her best to improve and dedicates her life to healing all who come to her as Happyaku Bikuni, it isn’t enough to free herself from the loop at the end of the designated thirty year period. It seemed to me reading the story as if it weren’t possible to escape it at all, even though the phoenix said that it might be. One thing that stood out to me was Kahei’s drawings being the inspiration for Tosa Mitsunobu’s paintings. I liked the idea that, even though it seems impossible for humanity to truly grow and change, it is still possible for them to create something meaningful from that experience.

I thought that Tezuka’s exploration of humanity in Life was one of his most interesting takes on the topic so far. I thought the comparison between the treatment of Juné’s grandma and Aoi’s clones was very interesting. Even though the grandma is almost entirely an android, and on a literal level “less human” than the clones, she is treated as a whole person simply due to the fact that she was born one. Meanwhile, the clones, who are human in every way except conception, are treated as inhuman completely. Although many other volumes explored the theme of humanity, the group being dehumanized in this scenario are exactly like humans, which blurs the lines even further. Making it unclear whether the Aoi that the reader follows until the end is in fact the original causes you to sympathize with him even if he may be a clone, which drives home Tezuka’s idea that each being should be treated with respect, whether or not they are technically “human”. This is best demonstrated in Juné’s final lines, which emphasize that it is humanity, as opposed to being a naturally occurring human, that is really important.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phoenix Vol. 9

Strange Beings

Although it was short, I enjoyed this story very much. At first, I felt like Sakon Suke’s eternal punishment was a little too severe since her reasons for letting her father die were well justified. I later realized that she found solace and peace by healing living beings and enjoyed being a nun. Although her life is cut short by being killed by a younger version of herself, she doesn’t mind because she has lived a good life and learned a lot from healing others. We also see the return of Saruta (in another form) as a cruel war leader who makes his daughter’s life miserable by depriving her of the people she loved. This is not only a reflection on the horrors of war but also the hardships of being born a woman in this era. This story also shows how humans are naturally inclined to fear or despise creatures that we aren’t familiar with when we should instead learn to empathize with them first.

Life

This chapter feels like it’s straight out of The Twilight Zone or Black Mirror (in a good way). The content is disturbing at times, especially with the killing of clones and the “love” between Aoi and June.

In contrast with the previous chapter, the protagonist Aoi is quite unlikeable, at least initially. He reminded me of Roc from Future. However, his transformation and the ending are pretty satisfying.

Many of the characters are driven by their own self-interests (ratings, wealth, fame) and obsessed with consumerism, tactlessly killing clones. Even Aoi lets his jealousy cloud his judgement when June explains how human society is cynical. The way Tezuka presents the story is equally callous. For example, he emotionally invests the reader into clone #2 only for him to be disintegrated in a mere instant.

The other theme that’s carried over from Strange Beings and Resurrection is the question, “What does it mean to be human?” Tezuka shows why the idea of making such a distinction is ridiculous, as all living beings are important. Similar to Sakon Suke, Aoi rectifies his past through karmic retribution. Nonetheless, the scene where the senior citizen cyborg is considered more human than the clones is obviously ridiculous, and small imperfections such as a missing finger determine whether someone is a human or not in this story. The following panel summarizes this message.

0 notes

Text

I think Robe of Feathers provides one of the strongest anti-war messages out of the past two volumes due to its brevity. In both the past and the future, characters are doomed to face the horrors of war, and there isn’t really a happy ending, which is applicable today.

Phoenix 8, Heike 2

Heike was a bit easier to follow because the section was focused more on the war than the politics. The difference between the portrayal of events in Phoenix and Heike differed similarly to the previous volume. The scene with the battle of the best archers at the river bank got dedramatized significantly in volume 8. It was no feat of skill, the battle’s outcome was just a result of natural forces.

The inspiring scene where the men ride steep cliff following the striking words of Yoshitsura is turned into one where a mountain woman contributes an idea.

To me, this scene reflects on the fact that these historical figures seem to have too many good ideas completely on their own to be believable.

Also, it felt like drowning was made a bit more tragic and absurd.

Another clear theme found in this volume regards betrayal and using others. The most immediate example is that of Yoshitsune. Obu seems rightly upset after the murder of gourd head and Obu. But here, he can continue to rationalize his actions. It seems to matter little to Yoshitsune how he actually is.

He says whatever he needs to justify his action to Obu. It would not be until toward the end of the volume and essentially the end to the running storyline that Benta finally does him in. I’m not sure what the message is supposed to be. Is it that power based on manipulation and relationships of utility runs out with the reasons to stay loyal? Or maybe it is that even the simplest can eventually have the power and reason to revolt against their political superiors? I’m kind of at a loss on what Benta in specific shows.

But more generally, Yoshitsune uses everyone he comes in contact with. In turn, few people actually trust him. Not even his brother is okay with the idea of Yoshitsune drinking the blood of the phoenix. So maybe Benta is actually just a vehicle for common people that experienced so much fear and suffering at Yoshitsune’s hands.

That got a bit dark. I think Tezuka would put in a comedic moment around this point.

Following the main storyline, the story of the monkey and dog introduced in the previous volume has further light shed on it. The absurdity of their struggles is revealed when it is just animals fighting over territory rather than humans that may delude themselves into thinking they are doing something greater by conquering than just fighting over territory, like leaving a lasting legacy or achieving a type of immortality.

Then there is a play in the manga. Or at least I think that is what it is. There is only one backdrop for the entire story. There is probably something to it that I’m missing. Maybe it is showing how the war affected people that were not characters in the thick of the plot.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I definitely enjoyed the bit about Akabe and Shirobe! I think this brings a new light to the idea of karma: it doesn’t necessarily punish people who were bad in their previous lives, but beings retain the same qualities that led them to live horrible lives.

Phoenix Vol VIII

This volume of Phoenix continued from last volume’s storlyine and was just as over the place as the last volume. It lasted from the final destruction of the Taira, to the invasion of the Fujiwara, to the “rebirth” of Yoshitsune and the Taira lord into the monkies that became the basis of the the story of the two graves in the previous volume.

Again, this volume as very dense and Tezuka brought up topics that were very philosophical in nature such as war and it’s repercussions. He mentions how war is always started by someone who in the end doesn’t have to suffer, and that those who do suffer are those who had no cause in starting the conflict. This could be seen in essence as damning of the Imperial Japanese government as well, in fact the whole subplot of Benta being forced to fight could be seen as a damnation of Imperial Japan and the subsequent suffering of its citizens during World War II.

Another philosophical topic Tezzuka brings up is the notion of power, to which he brings up in the context of animals as well.He notes how power struggles occur naturally everwhere yet in the end is fruitless as power will be lost in the end.

In addition, as normal for Tezuka, despite all the heavy philosophical topics brought up, still manages to make his work a little light hearted for the reader with several fourth wall breaks and anachronistic humor. One specific example is in the constant use of telephones for communication and in his reference to “manga” and thus breaking the fourth wall.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heike 2 / Phoenix Vol. 8: Civil War Pt 2 / Robe of Feathers

Heike 2

This passage from the Heike describes the battles between the Genji and Heike clans and the fall of the Heike. A common Japanese phrase, “rooting for the underdog”, seems to be the mantra here, since the Genji were much smaller than the Heike forces before others joined them. There are a few bad omens that lead to the fall of the Heike in battle: the killing of the deer in the beginning, the chickens that symbolized both sides, and the diving of the dolphins. The nun at the end describes this as karma for the sins of the emperor’s previous life before she sinks him in the sea.

Civil War Part Two

Volume 8 picks up where the last volume left off. I found the themes of the story much more defined in this part, and I liked how the story was resolved. Tezuka cleverly uses humor and satire not only as comic relief in the story, but also as a vehicle to drive his points.

The panels above summarize the main conflict of the story and its major themes of power, pride, love, and war. The story begs the questions, “Why do we need war? Why can’t people just live for themselves?” Regarding Japanese history, this refers to the unconditional devotion of samurais and how this tradition led to the events of WWII. Although the Heike appears to revere Yoshitsune, Civil War portrays him as a vengeful and power-seeking character who cares for nothing but his own ambition. It’s funny that most of the characters, even the “good” ones, still only care about pride and honor (i.e. Yoshinaka taunting Gourd-Head, Yoshitsune killing Gourd-Head for irritating him, Yoshinaka’s uncle wanting to kill himself for dishonoring his family, Yoshitsune being concerned about his rank).

Tezuka depicts war as a bad excuse for death and the lust for power. The characterization of Benta as “daft” is ironic; he cannot see the importance or justification of war and, to his benefit, can only see what really matters in life. This makes his final catharsis all the more satisfying.

Speaking of what really matters, the wise Master Myoun tells Yoshinaka before he dies that “all creatures that live must also die”, which is echoed throughout the series. Tezuka uses karma and reincarnation to prove his point: humans’ primal instinct may be to fight and arrange groups (as in the Akabe and Shirobe story, which serves a similar function to the slug people story of Volume 2), but they need to realize its futility and strive for living life for oneself.

Here’s another panel I liked.

Robe of Feathers

This was a really sad short story, but it accurately summarizes the events of the series and the themes of Civil War. It makes one feel that life is futile and not worth living since there is war in every time period, although Tezuka knows there is a cure for this that comes from within. I liked when the soldiers tried to drag Zuku into war as if it were a necessity, but they give in when they realize how much money they can make by selling the robe.

0 notes

Text

One theme that is highlighted at the time of Gao’s death and throughout the story (and series) is humanism. Gao emphasizes that everyone is equal when they die (which is a reference to Karma) and we should just live the lives that we have.

Heike 1, Phoenix 7 : Civil War

This week, I found that reading the Phoenix volume before reading Heike as well as taking notes of who was who as I read really helped me to keep all of the different names and characters straight. However, I still found the Heike reading a little bit confusing and difficult to get through, although I really enjoyed seeing what specifics of Tezuka’s writing are rooted in actually historical occurrences. I thought that the idea of Kiyomori using children essentially as spies (the Kaburo) was very interesting, and I was really fascinated by how Tezuka tied the themes of seeking eternal life and opposing government corruption into the story in his own way.

One thing that stuck with me from this volume of Phoenix was the reappearance of Saruta as Gao. Although this is definitely not the most significant thing to occur, I was genuinely caught off guard by his reappearance, as Tezuka seemed to leave his ending in his previous volume deliberately vague, but in a way that felt very final. I did enjoy seeing Gao reflect on his life as it neared its end, and his progression as a character seemed like Tezuka communicating to the reader that it is possible to redeem yourself from even the worst of circumstances and eventually reach a place of peace and satisfaction.

Another thing that I noted was that, although Kiyomori yearns for immortality in a similar way as others we’ve seen throughout the volumes, he has a sort of premonition in the form of a nightmare of what his eternal life might be like. It was interesting to me that seeing his own future suffering was not enough to deter him in his quest, and that earthly power and the continuation of his family line as the ruling class was more important to him.

I also feel like this volume had much more going on than is possible to include in a blog post of this length, but I don’t necessarily have a problem with it in the context of the story. I felt like I had a good handle on what was going on, and I liked seeing the simultaneous character developments of Benta, Ushiwaka, and especially Obu, who I think is one of the more compelling and better fleshed out female characters that Tezuka has written. It felt like Tezuka made a bit of a return to the comedy of the earlier volumes, and I feel like this was a possible attempt to cut through the density of the storyline he presents here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I think his obsession with getting the phoenix’s blood to “protect the clan” is really a disguise for his own desire for immortality. He says he’s protecting the clan when really he’s destroying his own clan by moving the capital in order to be closer to the phoenix.

Phoenix 7, Heike 1

In volume seven, the Tezuka returns to the past, criticizing more how ancient Japanese historical accounts. The Tale of Heike is being mirrored in volume seven. Tezuka’s take on the part where Kiyomi’s family was successful was sort of what I felt when I read it. Nepotism was definitely strong in that era. At least, I think that is what Tezuka wrote, seeing that if the entire family were so competent, there would be no fears about the future of the clan.

Themes concerning the nature of political units such as clans and the use of power continue.

I saw little criticism of the use of religion as a form of legitimation in this volume. Instead, it looks at the causes of successful revolt and the natural decline of powerful political organizations. One thing that stuck out to me on this topic is the scene where it is stated that those that possess a degree of power are the ones that can truly carry out a coup without being in absolute desperation.

This seems to have several implications, the most important of which, I believe is that there will be no analogous proleteriat revolution against mere corruption. When those in power are in accord, minor dissent is insufficient to spark a revolution. Even then, an unorganized mob with no support from skilled and intellectual classes above them (such as samurai and monks) will do little other than cause a drop in productivity or induce complete chaos.

Another theme that I found was one that continues from volume one and runs throughout the series. What does it mean for a clan to continue? A similar question of what it means for humanity to continue has been explored especially in-depth in volume two and volume six. But the idea of continuing a clan shows up most clearly in volumes one and seven. Whereas in volume one, the characters we follow seem to believe that begetting many children from the blood of a member of the village is a sufficient condition to rebuilding the village. In volume three, it is seen that it somewhat worked, with one of the descendants becoming a respected elder in a village, but ultimately, it was not the same as what was hoped for. There seems to be no real instance of reviving dead groups of beings, be it a village in volume one, humanity in volume two, or just a pure human lineage in volume six.

In volume seven, another attempt is made by a character to ensure that a clan continues. And this seems a bit strange to me. After finding out that he cannot simply marry a member of the clan off, Kiyomori turns to the phoenix. The prospect of immortality for the purpose of ensuring that his clan may continue completely swallows Kiyomori up.

It feels to me that there was no real clan if there was only one ruler that held everything together. While it is established that he believes that immortality from the phoenix’s blood will ensure he will never fear death, he also is shown to have nightmares about living until the end of the universe.

This makes his relationship with eternal life not a completely selfish one. His dedication to the cause of the clan, however, does not seem to be a dedication to something beyond himself. So what was it that drove him to desire the phoenix’s blood so much? I might just have missed a part that justifies him, but it seems to be just blind dogmatic belief that the clan must continue that pushes him to be so obsessed.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heiki 1 / Phoenix Vol. 7

Heiki 1

This passage from the Heike depicts the rule of Kiyomori, Japan’s Chancellor. It seems that Japan has had its fair share of militant dictators. Kiyomori seemed pious at first; when he was 51, he took Buddhist vows to save his life from illness and it worked. He was powerful and had a family that extended deep into Japan’s government. However, after burning Nara, which included many Buddhist monks and temples, he came down with a burning fever and died. His death is portrayed as karma for his authoritarian rule as a dictator. The excerpt emphasizes the ephemeral nature of life.

Phoenix Vol. 7: Civil War

Civil War (1172 – 1189 AD) takes place in the period of power of the Taira clan. The story closely follows the events of the Heiki and refers to themes from Karma, such as reincarnation. I found it hard to keep up with the numerous Japanese characters and names since the story has a deep and complex plot. The story also twists the characters of the Gikeiki a little (which Master Myoun is seen writing), with Benta portrayed as daft yet strong and loving (perhaps to a fault). This story is primarily satirical with quite a few humorous moments (the peacock phoenix, how dumb Benta is, the below picture).

Power is a major theme in this story. Unlike with Himiko from Dawn, Kiyomori assumed his power and privileges because he promised to protect the members of his clan, as did the samurai of Taira and mountain monks, however, they abuse this power when they use it to obtain women, money, and dominance (pictured below). This contrasts a character like Benta, who is not smart but has a good heart. Kiyomori is internally conflicted when he has to choose between power and love. He later becomes paranoid and ruthless with power after the coup d’état failed.

Tezuka also emphasizes how people shouldn’t live for other people or have clan allegiance, but instead live for themselves (humanism). Kiyomori even convinces himself that he’s trying to attain immortality to protect his clan when he’s really destroying his own people by moving the capital in order to attain immortality. It’s revealed through the Akabe and Shirobe mini-story that everyone is the same on the inside, and in a civil war, people hate each other without knowing who they are.

In this story, Obu, Kiyomori, and especially Benta are all unwilling to change their ways, as it is human nature to not welcome change, however, the story emphasizes the impermanence of relationships due to situations that characters are placed in.

0 notes

Text

I think this volume relates to the previous volume strongly. There’s still the idea that humans seem less human than robots and questions of what it means to be human. There’s also an appearance from Chihiro that highlights these concepts.

Phoenix Volume 6

This volume for me felt kind of separated from the main story as a whole. This volume was really dense, and at the end I really didn’t understand how it fit into the grand scale of things. This volume was really overall completely different from the other volumes, not saying that there is nothing to be learned in this volume, but the way it was presented is not like how we’ve seen it previously. For example, this volume was presented as a story being told by the phoenix, while the other volumes were made to be seen as a recollection of human history. Not only this, but, other than Nakamura being present, nothing connected this volume to the other one’s and the themes we usually see being developed are nowhere to be found.

First of all, we usually see the phoenix teaching some type of lesson but in this volume it’s not really like this. Throughout these volumes we’ve been able to see many different sides of the phoenix. In this volume, the phoenix takes the role of a guardian for Romi and Eden 17. This is the first time, i’ve seen the phoenix take such an active role, going through great lengths in order to ensure the survival of Romi and her descendants. Not only this, but the phoenix had guided them through space and ensured that she reached earth, which was completely surprising regarding how we’ve seen the phoenix act in previous volumes. But in the end, the phoenix ends up wiping out the entire planet, which leads you to think, why did it go through the struggle of ensuring their survival in the first place.

In the midst of all the absurdity of this volume though we can see some of topics and themes that Tezuka wants to develop. We are presented with the issue of overpopulation, where many of Earth’s inhabitants are basically forced to relocate. We also see the idea of corruption, being developed with the salesmen and the inhabitants of Eden 17. Even though the Eden 17 population can’t be blamed, Tezuka shows how quickly an innocent society can be corrupted. Another overarching theme, is the cyclical nature of life which can be recognized in many of the volumes of phoenix. This can be see with how Eden 17 collapsed and died out, but at the same time new life and a new civilization was just starting to grow. Overall this wasn’t one of my favorite volumes of the phoenix, but there are still many important themes and topics being developed in it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think you bring up interesting points! Perhaps the title, Nostalgia, is a reflection of the idea that a “home” or “family” or even “love” are subjective, as nostalgia is a feeling of longing for something that gave the subject happiness at some point.

Phoenix Volume 6

I found that a lot of this volume rested upon themes that were developed in previous future volumes.

This one in specific was a funny reference. But there was also the beginning of the volume that tells us how the story ends.

It seems that more than even before, Tezuka is getting serious on some of the broader themes regarding life. There are some casual mentions of some very interesting ideas. One example is that of what constitutes a real mother.

Chihiro reflects on the nature of friendship.

A more sustained look is done for the concept of a home.

All of this ties together to be an interesting reflection on the nature of the familiar and the natural. Home is not a location, just as a mother is not a biological entity. There is seems to be something more subjective that is difficult to put in material terms about some of our terms. By removing the usual occurence from the feeling itself, a question of what constitutes a being such as a mother is answered in a way that seems to suggest that it is not a physical being at all, but rather a role.

Similarly, the cliché phrase “home is where the heart is” seems to ring especially true. We see clearly that the strange alien world is far too alien. But what about the Earth that space colonists get so homesick of? Upon arrival, they experienced nothing but hardship. The only time that Earth felt comfortable was looking at the sunset. And even then, someone who was raised to never see the sun was the one that felt so at home with it. Overall, this volume seems to elevate the importance of human feelings and connections over semantic fact or physical and biological relations.

3 notes

·

View notes