Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

got your muffin! Thank youu!!! I didnt reply in time because tumblr ate up the ask :<

I baked a cake in return though. Even wrote a little frosting message on top too! ૮ • ﻌ - ა

https:// postimg.cc/6yhqRTph

(remove the space between “//“ and “postimg” beep boop!)

omg omg omg what a delightful surprise!!! one of my favorite aspects of Nabokov’s writing is how wonderfully complex and human his characters are and how that complexity is filtered through the narration. he never coddles the reader, he lets you sit in cognitive dissonance.

in Charlotte’s case, we get this deeply flawed mother who, despite everything, clearly cares about her daughter. but because it’s filtered through HH’s less-than-favorable (and deeply self-serving) perspective, it’s easy to read her as nothing but awful.

John Ray Jr. calls her an “egotistic mother” in the foreword, which tells you more about his smug little need to slot people into neat boxes than about Charlotte herself.

(Another Monster’s Weber would do the same thing.)

Charlotte’s multilayered. HH’s view of her is obviously distorted, but that’s the brilliance of unreliable narration—there’s always a kernel of truth. he takes the real tension between Lo and her mother and uses it as narrative fuel to give the reader this grotesque parody of a love triangle: mother and daughter fighting over a man.

but what really gets me is this—despite being charmed by HH, despite her strained relationship with Lo, Charlotte does react the second she finds out his true intentions. in similar situations, it’s not rare for mothers to shift the blame onto the kid and enable abuse.

there’s so much I could say about her. I love going back through HH’s exaggerations and tropes to reconstruct Nabokov’s full picture. her grieving her little boy is gutting. her cruelty toward Lo is real and painful and doesn’t cancel out her love. her presence lingering in HH’s mind after the accident is shuddering.

and she lives in Lo.

“She directed the dart of her cigarette, index rapidly tapping upon it, toward the hearth exactly as her mother used to do, and then, like her mother, oh my God, with her fingernail scratched and removed a fragment of cigarette paper from her underlip.”

this kind of detail. like fuck you Nabokov. seriously.

and Lo’s grief is devastating. especially when you remember HH actively withholds the truth from her. this goddamn moment where she’s trying to fill the gaps through fiction:

“Where is she buried anyway?” “Who?” “Oh, you know, my murdered mummy.” “And you know where her grave is,” I said controlling myself, whereupon I named the cemetery—just outside Ramsdale, between the railway tracks and Lakeview Hill. “Moreover,” I added, “the tragedy of such an accident is somewhat cheapened by the epithet you saw fit to apply to it. If you really wish to triumph in your mind over the idea of death—” “Ray,” said Lo for hurrah, and languidly left the room, and for a long while I stared with smarting eyes into the fire. Then I picked up her book. It was some trash for young people. There was a gloomy girl Marion, and there was her stepmother who turned out to be, against all expectations, a young, gay, understanding redhead who explained to Marion that Marion’s dead mother had really been a heroic woman since she had deliberately dissimulated her great love for Marion because she was dying, and did not want her child to miss her.

just—fuck.

and then there’s this quiet confession:

“I may also have relied too much on the abnormally chill relations between Charlotte and her daughter. But the awful point of the whole argument is this. It had become gradually clear to my conventional Lolita during our singular and bestial cohabitation that even the most miserable of family lives was better than the parody of incest, which, in the long run, was the best I could offer the waif.”

he knows. buried under all his literary gymnastics, HH knows exactly what he did.

HH’s own mother is a ghost—barely mentioned, completely absent, HH never processed her tragic death. he can’t stand the idea of a mother existing as something real, with agency and rage and grief and love. so he mocks Charlotte, distorts her, then gets rid of her.

so yeah—if you have a soft spot for fictional mothers, it makes perfect sense that Charlotte caught your attention. she’s a brilliant character. she’s all the things HH can’t handle: a woman who exists beyond the limits of his narrative.

thanks for the ask!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! <333333333333333333

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do do you think Kenzo Tenma has in parallel with Humbert Humbert from Lolita?

Okay, this isn't an ask I was expecting, LMAO, but let's give it a try, readers, please don't kill me for comparing Tenma to HH.

They both come to a foreign continent, and they're very much shaped by their exile, it's a crucial part of the story.

They are brilliant in their chosen fields.

HH marries Charlotte to be closer to Lo, Tenma plans to marry the director's daughter... While in HH's case it's without any doubt cold calculation, I don't think that Tenma was cynical, but I still don't think it's entirely a coincidence that he decided to propose to the daughter of the man he studied under. I think in Tenma's case it was more a matter of "well, that's the way things are".

They're both terrible at pretending they're attracted to women (I'm so sorry).

They bombard people close to them with gifts.

Their exes are women who have a drinking problem, were divorced three times, and who have serious mental health issues (not taken seriously enough).

They don't have a fixed place to live, they go from place to place, from hotel to hotel, from motel to motel, searching for the the beast’s lair with a loaded Ur-father’s central forelimb (ready for instant service on the person or persons) in their pockets.

They travel around with a kidnapped kid. Dieter is lucky that Tenma doesn't share HH's fucked-up tendencies, because no one would notice anyway.

They get really, really, really nervous around cops. The cops are useless and incompetent.

Their stories are shaped by characters who have some weird power over the narration; one is a Freudian psychologist who assures us that this remarkable memoir [Lolita] is presented intact, the other is a psychologist and psychiatrist (Nabokov's faves <3) who turned into a Freud-lookalike (Nabokov's absolute favorite guy <3) in his old days.

Lmao. Ten points. Thanks, anon, I enjoyed this a lot.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thought of death, which had once so frightened me, was now an intimate and simple affair. I was afraid, terribly afraid of the monstrous pain the bullet might cause me; but to be afraid of the black velvety sleep, of the even darkness, so much more acceptable and comprehensible than life’s motley insomnia? Nonsense—how could one be afraid of that?

Vladimir Nabokov, The Eye

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

i read lolita's foreword with Rudi Gillen's voice

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

you made me read lolita and I am 28 pages in and I can especially see how similar is the way HH and Hartman talks about children Johan and the "nymphette" are not children they are demons in children bodies completely different from the true innocent children they are a wonderful "work of art " from HH and hartmann and they both try to change the children around them to their vision of what they should be like

I'm always so giddy when people tell me I made them reach for Lolita!

Yes, Hartmann does the exact same thing HH does to Lo: he strips Johan out of his humanity and presents him as a demonic entity, as I mentioned in one of my earlier posts.

I rewatched his last scene recently and smirked at him calling Johan a "masterpiece" and his hysterical reaction to Dieter leaving him. Peak Humbert Humbert behavior. Not to mention his good (superficial) first impression.

And it's a bit... funny? to me that his words about the Kinderheim massacre are often taken at face value.

Thanks for the ask! Hope you're enjoying the book. ( ◜‿◝ )♡

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

franz bonaparta. what kind of bullshit fake name is this. are you alright my dude

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing these dedications in Nabokov's novels always makes me so soft

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nabokov’s bugs, Urasawa’s noses

Shout-out to @lily2929 for noticing that Bonaparta drew Věra with a smaller nose!

One of my favorite tricks in Lolita (and not only in Lolita) is the false clues planted in the text for the over-eager reader trying to get into Nabokov’s head.

Some of these false clues are the superficial similarities between Nabokov and Humbert Humbert:

Of course, he is a European and a man of letters as I am, but I have been very careful to separate myself from him. For instance, the good reader will notice that Humbert Humbert confuses hummingbirds with hawkmoths. Now I would never do that being an entomologist.

For someone unfamiliar with Nabokov and his works, this may seem like an odd difference to focus on; instead of distancing himself from HH’s tendencies, Nabokov decides to talk about a very obscure detail that many readers will miss.

And this is exactly the point—the obscure details are where the beauty of the story is hiding.

In reading, one should notice and fondle details. There is nothing wrong about the moonshine of generalization when it comes after the sunny trifles of the book have been lovingly collected. If one begins with a readymade generalization, one begins at the wrong end and travels away from the book before one has started to understand it.

In short: If a reader is busy hyperfocusing on generalities that superficially connect HH with his author, they will miss what truly matters, and what truly matters is the bigger picture created of tiny details.

Urasawa did something similar by giving Franz Bonaparta/Klaus Poppe his profession: a brainwashing picture book author. A significant difference is hidden in a tiny but crucial detail: how they draw noses.

Just like Nabokov would never confuse a hummingbird with a hawkmoth, Urasawa wouldn’t turn an aquiline nose into a conventionally attractive one!

Bonaparta isn’t the only character in Monster who shares some similarities with his creator; another one is Tenma: A well-educated Japanese man born on January 2nd.

It makes me wonder—and this is only my speculation since I don’t know Urasawa, I only know his work and some of his public persona—if he threw in these attention-grabbing similarities only to distance himself from his creation in less obvious details?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

the author's barely disguised longing for a kinder world

120K notes

·

View notes

Text

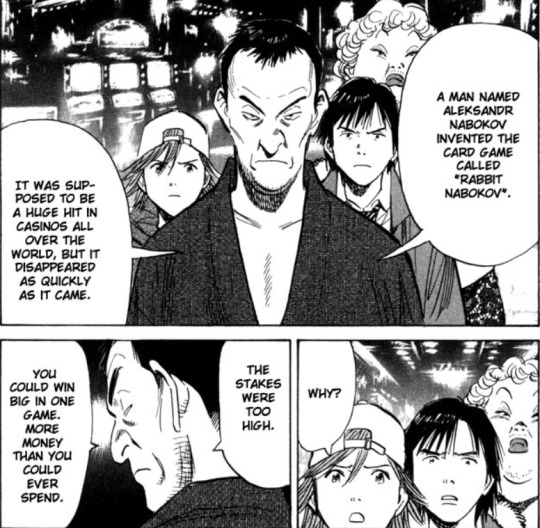

The game is called Rabbit Nabokov.

The game was made by Aleksandr Nabokov. Aleksandr Nabokov = Pushkin & Nabokov (Just like Bob Lennon = Bob Dylan and John Lennon).

Nabokov translated Pushkin, his friend Edmund Wilson was VERY critical of this translation.

The book with the correspondence between Vladimir and Emund is called: Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya. Bunny Volodya. (First published in 1979)

Bunny, Volodya. Rabbit Nabokov.

Rabbit Nabokov, Ruhenheim’s Konrad and Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin

Disclaimer: I haven’t read 20th Century Boys yet, so I apologize in advance for any inaccuracies (and you’re welcome to correct me!). I only wanted to take a look at the bizarre Rabbit Nabokov game.

I also haven’t read Nabokov’s translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, but I definitely plan to read it—at least fragments of it.

Keep in mind that these are only notes on a heavy work in progress. You’ll find the TL;DR version at the end.

Rabbit Nabokov is a fictional high-stakes gambling card game invented by a character named Aleksandr Nabokov.

The creator is a hybrid of two Russian authors: Aleksandr Pushkin and Vladimir Nabokov.

This isn’t the first time Urasawa used a real-world author’s name to create a fictional character; Monster introduced two characters named after one author: Karel Ranke and Petr Čapek.

So why is the fictional creator of a fictional gambling game named after two Russian authors?

For starters, card games are referenced in both Pushkin (The Queen of Spades) and Nabokov (King, Queen, Knave).

But there’s something more interesting and of substance, and it’s about Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, a milestone of Russian literature. Nabokov thought it was impossible to translate it faithfully while keeping the rhymes and he was dissapointed and disgusted with the already existing English translations of it (because he was a massive hater).

So his partner-in-crime wife, Véra, suggested he should create his own translation of the sacred text.

And these were the beginnings of a work with the following title:

Yes, this should be treated as a full title, because this isn’t just a translation of Eugene Onegin. Most of the text here is not, as one might think, the translation of the poem itself, but Nabokov’s commentary.

The commentary that turned a book of around 350 pages into a beast of around 1850 pages (dare I say, Charles Kinbote style?).

He also apologized for his own translation (!) in the form of a poem.

Taking all of this into account, one question arises: is this version of Eugene Onegin still only Pushkin’s work? Or did it evolve into its own thing?

Maybe we could say this is the work of Aleksandr Nabokov?

So why did this Aleksandr Nabokov create a gambling game? One clue can be found in Nabokov’s response to Edmund Wilson (someone Nabokov corresponded with for years), who was critical of Nabokov’s translation:

What does [N.] mean when he speaks of Pushkin’s ‘addiction to stuss’? This is not an English word, and if he means the Hebrew word for nonsense, which has been absorbed into German, it ought to be italicized and capitalized. But even on this assumption it hardly makes sense.”

This is Mr. Wilson’s nonsense, not mine. “Stuss” is the English name of a card game which I discuss at length in my notes on Pushkin’s addiction to gambling. Mr. Wilson should have consulted my notes (and Webster’s dictionary) more carefully.

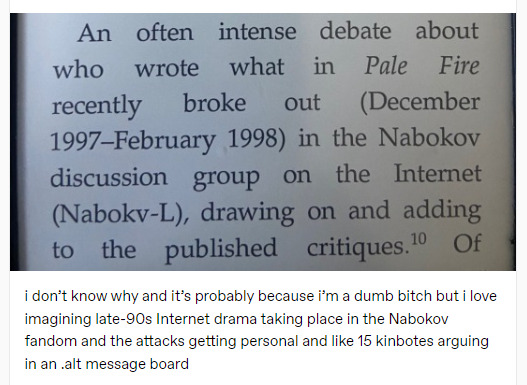

So here we have it: a card game and a gambling addiction. And it turns out that playing the game can turn into a scene that resembles your average discussion about Nabokov and/or his work.

Just to name one example with an adequate commentary:

The Eugene Onegin shenanigans don’t end with 20th Century Boys. They don’t even start here; they start with Monster.

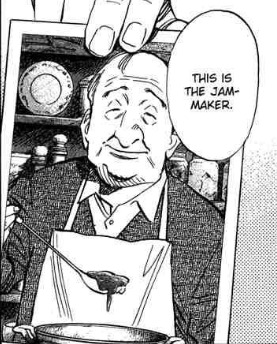

Remember Konrad? The lingonberry jam-maker from Ruhenheim? Aren’t the lingonberries an oddly specific choice for a character from a far-away background?

Lingonberries are present in Eugene Onegin.

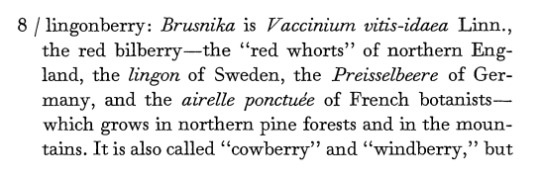

In his commentary, Nabokov devotes more than one page to explaining why he translated the Russian word Brusnika into lingonberry and why the other translations of brusnichnaya voda were, to say the least, inaccurate. Lingonberries can be deceitful.

TL;DR: Nabokov explains the confusing nature of lingonberries, shows no mercy to his translation predecessors and expects his successors to do better.

Konrad has other traits that make him a suspiciously Nabokovian character.

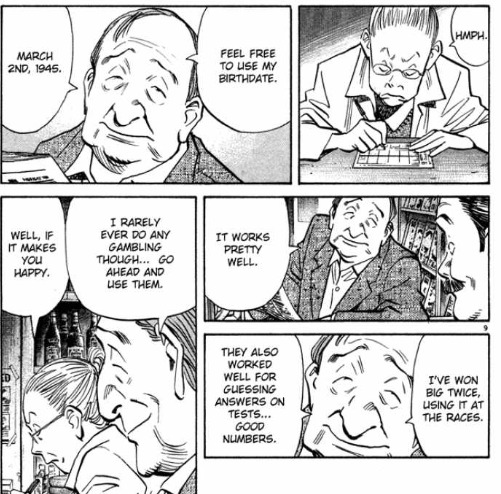

His birthday date seems to have some special powers:

Is he telling the truth or is he just making fun of Mrs. Heinich and her superstitions? Was it a mere coincidence that the numbers were a success? I guess we’ll never know!

This combines three things: the gambling, the coincidences and patterns, and the significant number.

Coincidences and patterns are one of the most important motifs in Nabokov’s work. To quote Lolita: Those dazzling coincidences that logicians loathe and poets love.

While reading Nabokov’s works, it can be useful to pay attention to the numbers; for example, 342 is a recurring number in Lolita.

And the gambling? Deception is an inherent part of gambling; it was also something Nabokov was clearly fascinated with.

Q: You say that reality is an intensely subjective matter, but in your books it seems to me that you seem to take an almost perverse delight in literary deception.

A: The fake move in a chess problem, the illusion of a solution or the conjuror's magic: I used to be a little conjuror when I was a boy. I loved doing simple tricks—turning water into wine, that kind of thing.

Literature is invention. Fiction is fiction. To call a story a true story is an insult to both art and truth. Every great writer is a great deceiver, but so is that arch-cheat Nature. Nature always deceives. From the simple deception of propagation to the prodigiously sophisticated illusion of protective colors in butterflies or birds, there is in Nature a marvelous system of spells and wiles. The writer of fiction only follows Nature’s lead.

And of course, his stories are full of (lonely, misunderstood, and often very dangerous) deceivers.

But let’s get back to Konrad, a good friend of Mr. Poppe:

One of the first things you might learn about Nabokov is that he despised Freud. So much that the traces of the Viennese quack can be tracked in his books everywhere; for example, Lolita opens with a fictional foreword written by a fictional Freudian psychologist called John Ray (Jr.).

Oh, I am not up to discussing again that figure of fun. He is not worthy of more attention than I have granted him in my novels and in Speak, Memory. Let the credulous and the vulgar continue to believe that all mental woes can be cured by a daily application of old Greek myths to their private parts. I really do not care.

Making the Nabokov-coded character friends with someone who turned into a Freud-lookalike in his old days (and who’s Monster’s greatest deceiver and a very Nabokovian character himself)? Letting them play Nabokov’s beloved chess?

It’s like using Nabokov’s tricks against him, which is hilarious.

Another fun fact about Nabokov: he loved annagrams and wordplay. For example, he inserted himself into Lolita using an anagram of his name, Vivian Darkbloom (of course the anagram of Nabokov’s name would be a dramatic and fabulous one; come on, it sounds like a draq queen name).

And while this is only partially an anagram, it’s still interesting that you can take some letters from Vladimir Nabokov to create a Konrad.

His corpse also looks to me like a middle-aged Nabokov, but since I’m biased as hell, I’ll leave it to your interpretation.

All the examples are something I thought about earlier but wasn’t sure enough to post it anywhere; the lingonberry seemed too general, the anagram wasn’t a full one, and the birthdate was the most suspicious thing to me, but still not enough to share it.

But the obscure Aleksandr Nabokov and his gambling card game are a very solid clue that binds it all together.

And since we’re talking about deceivers and translations, let me add a small easter egg: please get back to the The Secret Woods episode, pay close attention to Edmund ( ͡~ ͜ʖ ͡° ) Fahren, his suicide note, and see if there’s something possibly wrong with the translation of the passage found by Richard Braun.

TL;DR:

The gambling card game Rabbit Nabokov was created by a fictional man called Aleksandr Nabokov; Aleksandr is Pushkin’s first name. Nabokov is Vladimir’s last name.

Both Pushkin and Nabokov have referenced gaming cards in their works.

Nabokov translated Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin into English because he was deeply unsatisfied with the earlier translations. One of Nabokov’s many comments is about Pushkin’s gambling addiction and a card game.

Nabokov’s translation isn’t just a translation; it’s full of comments that turn it into its own thing, which can explain the hybrid that is Aleksandr Nabokov.

Ruhenheim’s Konrad is the real monster of Monster (besides Naoki Urasawa and his collaborator and editor Takashi Nagasaki), and I love him dearly.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

"all characters in lolita are bad people."

no, they aren't. they are filtered through HH who hates everyone, including himself.

About Valeria (it's not an "awful person" example, but it demonstrates well HH's incredible ability to banalize even the most painful details), his first wife, whom he married for his own safety:

She had a Nansen, or better say Nonsense, passport which for some reason a share in her husband’s solid Swiss citizenship could not easily transcend.

He calls her Nansen passport Nonsense passport which is a fun wordplay and, ngl, it makes me chuckle every time I read this line. But! Valeria is a Polish woman living in France after WWII.

The Nansen passport is a stateless persons passport. HH doesn't treat Valeria seriously, but the author does.

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

nobody:

humbert after making shit up to justify himself:

this is my sleep paralysis demon

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

lolita re-read update: I know that there's a scene where Dolly reads a "stranger danger" article but I didn't expect it to be right after H assaulted her on a couch?? hwat

I believe it's actually worse and more grotesque and it is while the assault is still ongoing. She's reading the paper to distract herself while he is either penetrating her or masturbating against her naked body (but I believe it's the former) and he notes her fascination with "odd" topics such as happy married couple photos and violent car crashes and then reads out the column over her shoulder.

What makes this scene even more painful and nauseating in my opinion (but also complex and brilliant) is that just a page earlier we can see she was doing exactly this in any way she could we just aren't primed to pay attention to it at that point:

She pointed out their license plate and how clearly she was nowhere near home, she tried to draw the attention of strangers (HH even calls them witnesses) who might remember them and their plates. And she used her "little claws", one of the very few times it's suggested she actually physically fought back against his assaults.

All of these are tiny asides and told in the typical Humbert fashion that you might just skim over them and not note their individual significance but the picture they form when you put the pieces together is so heartbreaking. I love this particular little section because it brings together almost everything that makes this book so brilliant. Making the reader work to fully grasp what is happening, the depth of Humbert's cruelty, the fierce intelligence and strength Dolly shows time and time again, the almost hysterical dark humor, the surprising accuracy and depth of research in how CSA is portrayed and treated. Hard to read as it may be it's a real hats off moment.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The mother in the Red Rose Mansion, the mother in the Les Violettes Pension.

Lolita isn’t the only novel written by Nabokov whose presence I can feel in Monster. Recently, I reread The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Nabokov’s first novel written in English, and discovered that it’s a big playground of connections.

Sebastian Knight is a famous fictional writer who died, aged 36, of a fictional heart disease called Lehmann’s disease. V., his younger half-brother, attempts to understand all the nuances of his enigmatic life and write his biography.

Sebastian is depicted through fragmented memories, a narrative technique that finds its echo in Monster. In this note, I want to focus on Johan Liebert, whose image is also shaped by other’s recollections.

Sebastian and Johan share many similarities; both are of double parentage (English and Russian for Sebastian, Czech and German for Johan), both were abandoned by their mothers—under tragic circumstances—when they were little boys, both travel constantly searching for their identity, and both remain enigmas to those seeking them (V. for Sebastian, Nina and Tenma for Johan).

Both embark on a search for traces of their mothers as young men: Johan in the Red Rose Mansion in Czechia, Sebastian in Les Violettes in France.

Sebastian describes the quest in one of his novels with great detail:

One day I went for a long walk and found a place called Roquebrune. It was at Roquebrune that my mother had died thirteen years before. I well remember the day my father told me of her death and the name of the pension where it occurred. The name was ‘Les Violettes.’ (...) I sat down on a blue bench under a great eucalyptus, its bark half stripped away, as seems to be always the case with this sort of tree. Then I tried to see the pink house and the tree and the whole complexion of the place as my mother had seen it. I regretted not knowing the exact window of her room. (...) Gradually I worked myself into such a state that for a moment the pink and green seemed to shimmer and oat as if seen through a veil of mist. My mother, a dim slight gure in a large hat, went slowly up the steps which seemed to dissolve into water.

The hat is a crucial element, carrying great emotional depth. Virginia wore one when Sebastian saw her for the last time, a year before her death.

V. presents the meeting as follows:

She arrived by the Nord Express on a winter day, without the slightest warning, and sent a curt note asking to see her son. My father was away in the country on a bear-hunt; so my mother quietly took Sebastian to the Hotel d’Europe where Virginia had put up for a single afternoon. There, in the hall, she saw her husband’s first wife, a slim, slightly angular woman, with a small quivering face under a huge black hat. She had raised her veil above her lips to kiss the boy, and no sooner had she touched him than she burst into tears, as if Sebastian’s warm tender temple was the very source and satiety of her sorrow.

Later, Sebastian finds out that his mother died in the other Roquebrune, which only emphasizes the fictional nature of this encounter:

Some months later in London I happened to meet a cousin of hers. A turn of the conversation led me to mention that I had visited the place where she had died. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘but it was the other Roquebrune, the one in the Var.

In Monster, Johan’s encounter with his mother’s image follows a similar pattern: he sees the painting in a place that was supposed to be the place of her death (I’m talking here about the cover-up discussed in Another Monster), but is not; the real Věra is in Southern France (yes, both Roquebrunes are also in Southern France, what a coincidence!).

The figure in the painting is, like Sebastian’s imagination of Virginia, only a ghost. A tragic reminder that, just as Sebastian could never fully trace his mother, Johan will also never find her by following the clues.

Both Sebastian and Johan see their mothers as inseparable parts of themselves. Sebastian uses his mother’s last name as his pen name, has her restlessness, and even dies of the same heart disease.

She was an inveterate traveller, always on the move and alike at home in any small pension or expensive hotel, home only meaning to her the comfort of constant change; from her, Sebastian inherited that strange, almost romantic, passion for sleeping-cars and Great European Express Trains.

*

I suddenly realised that my name conveyed nothing to him. Sebastian had made his mother’s name his own very completely

Johan says: She is me, and I am her. You are me, and I am you.

These words remind me of V.’s last words in the novel:

Sebastian’s mask clings to my face, the likeness will not be washed off. I am Sebastian, or Sebastian is I, or perhaps we both are someone whom neither of us knows.

Easter egg time! There’s a wink to Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

Third story: Sebastian speaking of his very first novel (unpublished and destroyed) explained that it was about a fat young student who travels home to find his mother married to his uncle; this uncle, an ear-specialist, had murdered the student’s father.

You know what this reminds me of, right?

#sebastian also reminds me a lot of tenma and bonaparta#but that's for another time#naoki urasawa's monster#monster manga#the real life of sebastian knight#other nabokovs#johan liebert#johan monster

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm currently reading through the part where HH describes his pre-Valeria "flings", and man, reading about Marie makes me sad, because a lot of girls still go through the same thing :( Nabokov really aired out a whole lot of society's dirty laundry in Lolita huh

"[Lolita] was a great pleasure to write, but it was also very painful. I had to read so many case histories." (Nabokov in a Vogue interview with Penelope Gilliatt, 1966)

The small glimpses we get of other exploited kids are heartbreaking. Marie, Monique, the other kids at Quilty's ranch, the boys abused by Gaston Godin... it's really incredible and something I don't think a lot of people realize nowadays with how comparatively educated we are about CSA how precise and accurate Nabokov was in his depictions of CSA and the ways it is normalised or overlooked in society. Nabokov started working on the seeds of Lolita in the 1930s and published in 1955. Child sexual abuse was only recognised legally as a form of abuse in the United States in 1973. Child pornography was outlawed in the US in 1978. The first description of grooming as a concept in literature is dated to 1979 and the first printed use of the term to 1984. At the time Nabokov was writing there was not only barely any academic writing on the subject there wasn't even the awareness that it was a problem in the general population or law enforcement.

I recommend Still Intrigued with Lolita: Nabokov’s Visionary Work on Child Sexual Abuse by Lucia C. A. Williams and Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita: The Representation and the Reality Re-Examining Lolita In the Light of Research into Child Sexual Abuse by Lawrence Ratna here for some research on the topic that puts things in perspective. It's painful to think about how prescient the novel still is but, on the other hand, looking back to how things were when Nabokov was writing we HAVE made some incredible progress and that's a small comfort at least.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey! i love your takes on lolita and monster but i’ve got to ask: where is that mashup idea coming from?

Hi and thank you!

There might have been no Monita at all if I didn't connect Tenma and Bonaparta in the first place, because as I was working on my very first draft, I thought to myself: damn. Why does Bonaparta remind me of Humbert Humbert so much?

And I started digging a little bit deeper (it was then when I noticed the Rabbit Nabokov game in 20th Century Boys for the first time and couldn't understand why Aleksandr Nabokov? Why a card game? What the hell is going on here?) and thought that it would be fun to make a comparative analysis of Humbert Humbert and Bonaparta.

I thought this was it! Yeet a HH and Bonaparta comparison and move on. But then I reread more Lolita, read more about Lolita, reread/rewatched Monster, and discovered that the similarities go way beyond one character; I can read/watch the whole animanga through Lolita.

(And we can go here beyond it as well, because I started comparing other Nabokov's works to Monster; currently, I'm rereading fragments of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and I'm already planning to write a silly little thing about Johan and his visit at the Red Rose Mansion when he was presenting himself as Anna).

Monster and Lolita scratch the same parts of my brain (or should I say: spine?), I found in Urasawa's work the same emotional depth and intensity I find in Nabokov's work, the same astounding attention to detail, the aesthethic bliss, the simultaneous satiation and insatiability (perfect combination), and much, much more.

This seemingly small detail grows in significance if we know that fleeting glimpses into a character’s suffering are usually key passages in Nabokov’s fiction.

I think this is also something than can be said about Monster.

I'm generally fascinated with the intertextuality of Monster, I love the way it references/quotes so many works from different genres while not copying them but instead creating something unique.

Ooops, I think that's enough dickriding for one ask. <3

Thanks for the message! (ᴗ͈ˬᴗ͈)ꕤ.゚

5 notes

·

View notes