Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

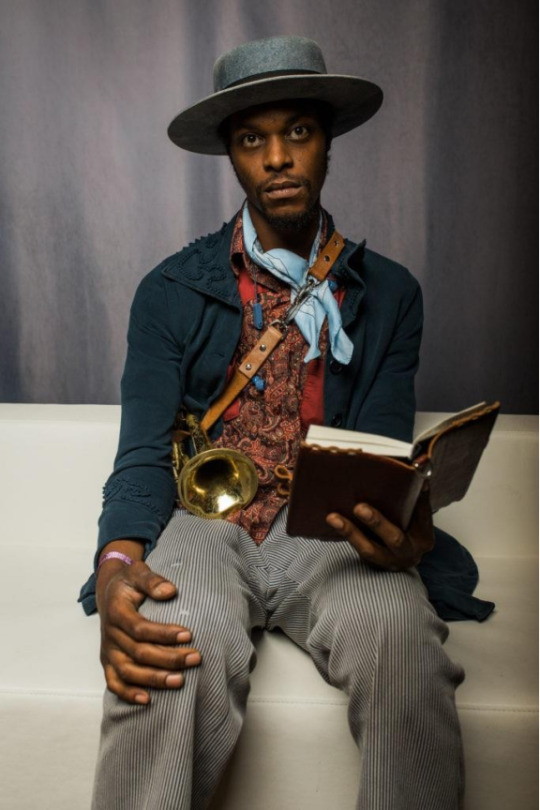

Tempesst-Music for Tempestuous Times

Oct 29, 2020

By Mossy Ross

Credit: Gyorgy Laszlo

Tempesst could be a band that’s one marijuana puff and a mushroom trip away from being a Ken Kesey novel. But they’re too smart for that. Maybe the rockstars of yore could stay up for days on end, free-lovin’ and festival-in,’ tripping balls for days on end. Or if we’re talking the 70s, snorting lines off of supermodels’ asses, and shooting up in the dingy downstairs bathrooms of, what are now, legendary music venues. But escapism is so last century. Now, the music venues have been replaced with condos. Our planet is facing extinction. Political unrest is threatening democracies. Social media is taking over our lives. And for many of us, a future with job security and healthcare is unlikely. But that isn’t stopping Tempesst. They’ve realized there’s nowhere to run, so might as well face the future head on…while still hanging on to what seemed like a much fun-ner past.

Tempesst’s dreamy new album, appropriately titled “Must Be a Dream,” makes existential crises seem romantic. Their flavor of rock is one of my favorite kinds…pretty. Tempesst shows us that the shitty parts of life don’t always have to lead to screaming anger, but that something beautiful can come out of asking the hard questions. Their retro style gives the modern problems they sing about a feeling of comforting nostalgia. Showing us that we can still slip on a polyester suit, get behind a Hammond organ, and rock out; while being honest about the terrifying future we face. Tempesst reminds us that if all else fails, we always have an analog world to go back to. And that might not be such a bad thing.

Before you read my chat with lead singer, Toma Benjamin, start going down the rabbit hole with Tempesst by watching their video for “Mushroom Cloud.” It not only has addictive visuals, but three of my favorite things: kitschy decor, a man in makeup, and a slammin’ saxophone solo.

youtube

Mossy: What’s your band’s history?

TB: The four of us, Blake, Cain, Andy, and I are from the same town in Australia. It’s a collection of towns. But the closest, most famous of the towns, is called Noosa. It’s a little beach town. So Cain, Andy, and I grew up with each other. But Blake’s actually about five years younger, so I met Blake because he lived three houses down the road. But it wasn’t until we were all in London, that we were just part of two groups that happened to come together, and all of these sorts of coincidences. I suppose when you move to a new city, for us coming all the way from Australia, you tend to find other people who have done the same thing. And then you bond, because you’ve got this similar experience of leaving home behind, and coming to this new city.

Mossy: What brought you to London?

TB: We were in New York, and we would’ve loved to stay in America. We were trying to get a visa to come stay in the states. And we got this business visa through my dad’s film distribution company. He distributes all the really bad B-grade films before the internet. People would actually buy the rights for them and distribute them across Australasia, which is pretty hilarious. This was in the 90s and 2000s. So we got a business visa to stay in the U.S., but you had to renew itall the time. So we renewed it once, and we tried to renew it again, but they wouldn’t let us. So we had to pack up all of our shit in thirty days and go back to Australia. And after growing up and spending all this time in this little coastal town in Australia, and then going to the complete opposite end of the spectrum, living in New York and experiencing the city and the energy, it was just too hard to stay home. So we lasted about three months and then we were like, “Well if we can’t go to New York, where else can we go?” So, not so very romantic (Laughs). It was for practical reasons. We could easily get a visa to come to London, and then we fell in love with the place after coming here.

Mossy: I always have to ask people from England or Australia who their influences are. I feel like there’s always such refined musical tastes coming from those two countries. Who were you listening to growing up?

TB: I’m a little bit of a late bloomer, to be honest. We grew up in quite a sheltered environment. Our families are quite religious. Myself and Andy grew up playing music in church. So it wasn’t until I left that world when I was about eighteen, that I started to learn about other artists. And I was really lucky to have a close friend who was actually playing with us in the original Tempesst, when we first started the band. And he’s a music lover and would spend all of his time listening to music from all over the place, and would just introduce us to some really great art. And then when I moved to New York, he also moved with me to New York. And I would say moving to New York introduced me to a lot of DIY bands like Yeasayer and Darwin Deez. When I was there, they were really big, and it was kind of the first time for me listening to that.

So getting into all the classic albums that I love now, that didn’t happen until well and truly in my twenties. And that was just because of my circumstance. But when I did start listening, it was just all the classics. I was just trying to catch up. Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley was one of my initial favorites. I still feel sometimes like I’m catching up. There’s just so much great music to consume, and not enough time to do it. And sometimes when you’re making music all day, the last thing you feel like doing is listening to music. So it’s kind of strange, I find myself listening to Talkback radio. I feel like I’m a 70 year-old man. (Laughs)

Mossy: What religion?

TB: Like Pentacostal, Christian. So yeah, I had some R&B gospel influences. My dad used to listen to George Benson, so I would try and mimic George Benson by playing guitar like George Benson, and singing the melodies with the guitar line. He might have listened to the odd Beatles song. But yeah, it wasn’t like my dad was listening to, like, really cool obscure records and introducing me to his favorite artists. He didn’t give a shit. (Laughs) He was listening to Christian music.

Mossy: I’m always surprised at how many rock musicians I talk to who grew up religious. I always assumed they would have had the cool dad who listened to obscure records, but a lot of them were sheltered and didn’t get to hear any of that. It’s almost like that upbringing helps you create a really original sound, because you didn’t have those influences around you when you were growing up.

Credit: Gyorgy Laszlo

Your sonic landscape matches your aesthetic. The way you present yourselves. Is that life imitating art, or art imitating life?

TB: I wouldn’t say there was any intention. I think there’s certain music you feel inspired by, and there’s certain fashion that you like, and it tends to be that all of these things come from that same world for us. I would also say that sonically, a lot of the equipment we use is old, vintage equipment. We’ve got vintage synths and our desk is a 1979 Neve console, and it sounds like an old school desk. So I think it just so happens that that’s the kind of music we’re into. We’re influenced by the artists that led us to have a think about what kind of instruments or gear we want, and it just naturally creates this specific sound.

Mossy: Why the extra “s” in Tempesst?

TB: We originally spelled Tempesst with one “s.” But soon after, we found that there was a 20-year old Celtic rock band that had the name already. When we started releasing music, Spotify started listing our music on their band page.

Mossy: Where did you shoot the video for “Mushroom Cloud?”

TB: An old workmens hall here around the corner in Islington. It’s a little hall that you can hire out, and we just thought it was funky and fit the vibe of the song.

Mossy: Tell me about your album cover.

TB: That was done by a guy named Jose Mendez. We basically sent the record out to a bunch of artists, and asked them to send us back what the sound of the album would look like. And Jose sent us back this sketch. The ways he was describing the songs felt like he really understood what we were trying to say. And then when he sent us the sketch, we all felt like it was really cool and trippy, and quite bold. And we wanted the music to feel quite bold and unpredictable. So I guess what we loved about it, was that it felt very bold and sort of random. Some of the ways he personified the characters in the songs were really cool.

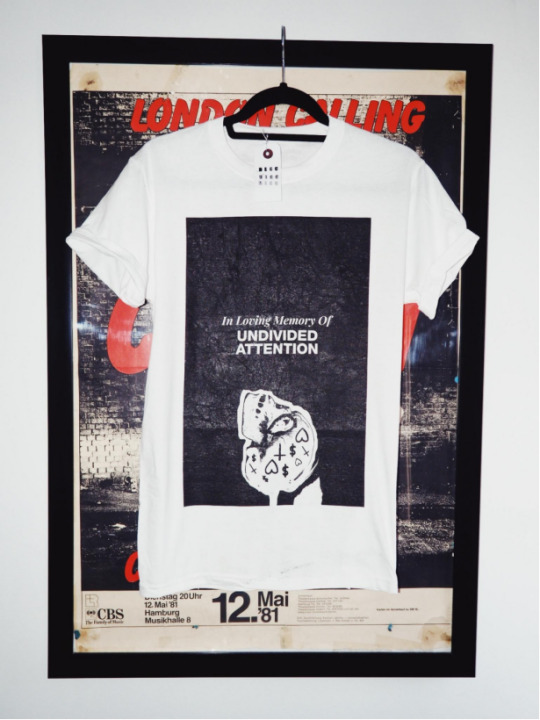

Mossy: How would you describe the Age of the Bored (the title of a song off their new album)?

TB: I would describe it as insular. I would describe it as a waste. It was actually Eric that came up with the lyrical concept, and we wrote the lyrics together. I think the frustration came from life caught in the vacuum of this device that sits by our bedside, and in our pocket, in a holder in the car. It’s literally your entire life is linked to this device, and all of the things that distract you, and pull your attention away from the things you should be doing. It’s like a loud voice just demanding your attention. Binging with messages and fucking emails, and everything just taking you off your focus. When I come in to the studio now, I leave my phone in my pocket, hang my jacket up behind the door, and it sits there all day. Because otherwise you find that your whole life is ruled by this device. As opposed to it being something that serves you, it actually takes over. So the idea of that song was just choosing to separate yourself from it at times, and not have this symbiotic relationship with your mobile phone. Everything comes from this idea of not wanting to waste. That life is precious and we only have limited time.

Credit: Gyorgy Laszlo

Mossy: I think it’s great when people who aren’t old, are telling people things that some people don’t realize unless they’re old. It takes a lot of self awareness to admit that this device gives you anxiety, and keeps you from being in the moment, and that you don’t have to have it by you all the time. I think it’s important for people to say that.

TB: One of my favorite lines in the whole record is in that song. It’s, “Offline, the new underground way to unwind.” How strange is it that, like, if you say to someone “I left my phone at home today,” they’re like, “What!? You have to go home!” It’s this bizarre idea that if you wanna unwind, if you wanna feel free, if you don’t wanna feel anxious, you don’t want to be ruled by this device and you leave your phone at home, people just freak out.

Mossy: It’s like a form of rebellion to leave your phone behind.

TB: Yeah, because we have lived in both worlds. So it’s like, you have the contrast. And it’s terrifying to think that at some point, if you have kids or whatever, that they’re gonna live in the world, and they won’t have that contrast. They won’t know what it’s like not to live with a mobile phone. It really will be a very different thing for someone to have that separation from their phone.

Mossy: “Is That All There Is?” also seems to have a message that speaks to a lot of people.

TB: I think again, it’s just another chance to talk about something that feels a little bit silly. That we aren’t always the best stewards of our time. That song’s probably more focused on a time of reflection. What happens is every year, I go back home for Christmas. And it’s a really strange time, because I have this contrast of leaving my busy life in London, and going back to this little beach town, and sitting on the beach. And I’m in this new environment, observing the people in that environment, reflecting on my year. And then the contrast always brings up these questions. For example in that song, “Is this it? Is this all we do? Just work our asses off all year?” And sometimes questioning even the whole creative process, and the creative lifestyle. And even questioning if that’s something that has merit. Does the world need more music? Does the world need another person trying to share their ideas? You’re grappling with this tension as an artist, wondering if the world needs any more fucking artists. (Laughs) There’s so much amazing music, you couldn’t possibly consume it all in one lifetime. And it’s also about just working out and reconciling with just growing up. That we’re not young forever. And we’ll have to, at some point, accept our mortality. And it’s that time when I go back to Australia, and I stop the busy-ness, and I’m sitting on the beach…that I get tormented with all these ideas. (Laughs)

Listen to “Must Be a Dream” on all streaming platforms or, better yet, buy it on vinyl.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Coocoo Banana-” Album of the Coocoo Banana Year

Oct 23, 2020

By Mossy Ross

Photo: Bjorn Magnusson

Lizzy Young. She’s smart. She’s funny. She has a song called “She Farts While She Walks.” Which, I have to say, has become my favorite tune to listen to when I find myself on the Upper East Side. There’s just something so very satisfying about watching posh, refined women bustling around, while someone sings “she farts while she walks” in my ears. Lizzy has an uncanny ability to have a laugh at life’s expense. She delivers truth in a deadpan voice, over hypnotic beats and beautifully textured melodies. She’s the friend you wish you had in high school. Where she’d not only have a snappy comeback for backtalkers, she’d elegantly deliver her sass with a French accent.

Lizzy Young’s debut album “Coocoo Banana” (out today), is truly revolutionary. Young is showing us that women don’t necessarily need to shout to be heard. That maybe the best way to right the injustices of our past, is by quietly taking the reigns instead. To lead by example with new attitudes and ideas. In her album, Young paves a way for empowerment, by showing us how to calmly laugh at life, while still admitting to how fucking depressing it can be.

In her video for “Obvious,” Young wildly and badass-edly destroys a car, while seeming to poke fun at how silly it is that we sometimes need to be told the simplest of facts. Possibly because we’re increasingly becoming unthinking people, who probably use common sense way less than we should.

What Lizzy Young’s album is telling us that’s not always so obvious, is that there actually were some good things to come out of 2020.

Mossy: Where does the name Lizzy Young come from?

LY: I used to have this project called Young Cleaners. And I really love the French musician, Lizzy Mercier Descloux. So I just thought it would be cool to use her name, and then use Young from the Young Cleaners.

Mossy: You have an interesting background. How would you describe your life?

LY: I grew up in a suburb of Paris. I have a small family, just a brother and my parents. I guess I had kind of a bit of a hard childhood. I don’t have a really good relationship with my parents. Now it’s a little bit better, but I think very young, I felt like I had to go. So I lived in Paris for awhile, and then I moved to Barcelona. I’m an actress, so I studied theater for awhile there. I left Paris when I turned 23, and I left home when I was 18, when I could legally leave.

Mossy: So you said you and your family are better now. How did that come to pass?

LY: I guess just being far away helped a lot, at least for me to try to figure out who I was, and what I wanted to do with my life, and how to do it. Growing up, I had absolutely no guidance. So every decision I took, was sometimes just out of my feelings. It was not always very thought out. And I was on my own really, so it took a lot of time. And forgiveness I think, is the key. I’m still working on it, but I feel like I’m getting closer every day to finally forgive. I don’t think there’s any other way, really. Because in the end, (parents are) people, too, and they struggle. It’s hard to look at people and try to take them out of their suffering, I guess.

Mossy: Especially parents. Because you think they’re supposed to fulfill this role, and when they don’t, there can be a lot of trauma that comes from that.

LY: Yeah, and a lot of insecurity. For me the hardest was to feel confident, and this album is like a dream of mine. I never had the courage to say, “Okay, this is my music, this is what I do.” I always played music with other people, hiding a lot. And I don’t know, I always wanted to do it, but never had the courage. So I think that’s a big one for me right now, because it’s something I needed to do. To tell my stories through my songs, and get it out of myself.

Mossy: What gave you that courage?

LY: I would say a fear of dying. I had a health scare that made me think it was now or never.

Photo: Samuel Tressler IV

Mossy: So once you left Paris, you went to Barcelona?

LY: Yeah, I studied theater there for two years. I had my first punk band there actually, in Barcelona, a little more than ten years ago. My bandmate and I were a duo. She was playing drums, and I was playing bass, and we were wearing mini burkas. (Laughs) So we don’t show the face, but we show the ass. And I was just basically yelling in a microphone. And then I felt like I needed to come to New York, because all of my favorite bands at that time were in New York. I wanted to play rock and roll and make noise.

Mossy: What were your favvorite bands then?

LY: I used to listen to a lot of Sonic Youth and Spacemen 3, Spiritualized. Kind of that vibe.

Mossy: I was watching a commercial for St. Vincent’s master class, and she talks about how she walks people through her songwriting process. I was thinking that, if I were to teach people my songwriting process, my method would be: drink a bottle of Jameson, smoke a couple spliffs…and see what happens. What’s yours?

LY: (Laughs) That would be so much funnier! Yeah, I used a little bit of mushrooms, a lot of water. I was very inspired at that time. I was writing songs very fast. As soon as I started it was very fast. I have a very hard time finishing things. I always think everything I do is not good enough, so it was hard to finish. I almost gave up, like, a hundred times.

Mossy: Where did the name “Coocoo Banana” come from?

LY: I used to say “coocoo banana” when I felt like people were going crazy, and then I went crazy. Because basically this allbum is kind of the story of my experience going through all these things in my life, and also the fear of dying. I’ve always been very scared of death, and I feel like the entire album is about death sometimes. (Laughs) But it’s not in a way that it’s always obvious. But a lot of it is that. And so I just felt like “coocoo banana” was a good way to summarize the feeling of this time. I like humor a lot, I like to laugh. And I feel like it’s hard to have a real good tragedy without having a little bit of humor in that. So I’m trying to mix everything together.

Mossy: Can we talk about “Kill All the Men?”

LY: (Laughs) Yeah, it’s, uh, pretty clear, I guess. (Laughs) I’m just so tired of everything. I feel like everything is just a box now. Everything has to be labeled and explained. And sexuality has to be up front, and I feel like people care too much about nothing. It’s all about money.

That’s what’s so disgusting. It’s not a real thing. It’s just a way for people to make money. It’s product. That’s what really bothers me. Because I think it’s good to talk about it. People should live their lives. But it just gets to this point where it becomes a product, and I just find it really strange. And boring. It’s like you know, God, there’s no character anymore in anything. It just feels like, kind of washed out a little bit.

Mossy: Do you think we should kill all the men?

LY: I think sometimes, yes! (Laughs) I mean, I love men, too. I have a lot of friends that are male friends. It’s just, I think in general, they’re disgusting. And it’s hard to be a woman because of that. Just my album for example. So many people, the first thing they ask me is, “Who did you work with? Did you do everything alone?” It’s like, oh I’m a woman, obviously, I can’t do shit because I’m a woman. Yeah, I think I’m upset with the men. (Laughs)

Photo: Samuel Tressler IV

Mossy: Does the car in the video for “Obvious” have a story?

LY: In the quarantine, I went and hid at my friend’s farm. So we spent the time making videos for my album. We made eight music videos, and that one was the last one. He had a BMW, and he sold the car to this guy who was not paying him. I always had this dream of going and breaking a car. So I said, “Okay let’s go. Let’s take a baseball bat to the car you just sold to the guy.” But a couple days later, the guy actually ended up paying for the car. So my friend found this car on Facebook Marketplace for very cheap, and we picked up the car, and it doesn’t look like it, but the car is a piece of shit. And we painted it and made it nice, and then I finally got to try to break it. But apparently German cars are very strong. (Laughs) So I failed.

Mossy: I don’t know French, so what is “Elephants” about?

LY: I was working at this bar in Brooklyn, and I started thinking about how people behave when they’re drunk, and how annoying it is sometimes. Feels like you’re babysitting. I mean, this song is about many different things. Also the beginning of Instagram. Just the feeling of all these images taking over the world, and how we just end up kind of being sad, I guess. I think sometimes it’s depressing. And it’s a lot of waste of time. I have a weird relationship with social media.

Mossy: What is it?

LY: I hate it. It’s not really my personality. I just feel like people really like to see you, and I have a hard time with my image. I just find it weird and disturbing sometimes that everyone is addicted to it. I feel like everybody is living these weird, fake lives. And it’s a lot of people, you know? And sometimes you want to not have to deal with that many people in your life. You just want to have the people you have to deal with already, and I feel like social media is just so much sometimes. It’s like the universe.

Mossy: What is it about your image that you’re not comfortable with?

LY: I guess I don’t like too much of my face. When I was growing up, I had really bad eczema on my face, and I think that distorted my vision. I’ve been struggling with that. Sometimes I feel like I have a distorted view, even though I’m an actress, which is absolutely insane. I don’t really like watching myself. I might have one of those mental sicknesses, you know, where you see yourself in a weird way? Or maybe I’m just a victim of society. (Laughs) It’s just so hard to be a woman sometimes and I have a hard time with that.

Mossy: It might just be as simple as you’re not fucking vain.

LY: (Laughs)

Mossy: You said you were a party girl. Any juicy stories?

LY: (Laughs) I used to work in this club in Barcelona, and I used to go there really early when they opened, and I used to go there and do cartwheels in the club. That’s a silly story. But…there were many, many parties. That’s why I left, actually. I was thinking if I stayed there, I would just party inside out. (Laughs) I’m not gonna do anything else with my life.

Check out the stunning new video for the album’s title track “Coocoo Banana,” and listen to the entire album out today!

Lizzy Young is on IG @lizzyyoung

Support independent artists by purchasing the album at https://lizzyyoung.bandcamp.com/releases

0 notes

Text

Thao Nguyen Doesn’t Stay Down

Oct 8, 2020

By Mossy Ross

Photo Credit: Shane McCauley

When I first listened to the title track off Thao & the Get Down Stay Down’s fifth album, Temple, I immediately hit repeat. After I finished listening to it the second time, I hit repeat again. And then again. And then again. I had a teenage urge to learn all the lyrics, so I could sing along at the top of my voice while cruising down the road. The song describes the pain of losing a home to war, an experience many of us haven’t lived through in America, and yet I still felt a deep personal connection with the song’s powerful message. Perhaps because this country is currently facing such extreme civil unrest, so the thought of experiencing war firsthand is increasingly becoming more real. But the song also touches on the turmoil we can sometimes feel in our own family lives as well. Thao Nguyen seems to be a master at crafting albums that exquisitely make complicated and painful matters a bit easier to bear.

Thao recently won a Sunny Award by CBS Sunday Morning (my most favorite of all morning shows) for the music video to her song “Phenom.” Not only is the video wildly creative and entertaining, it conveys an intergenerational rage that’s finally being collectively realized. It’s the rage of someone who has discovered it’s okay to feel sick of constantly being at the bottom of the ladder, and the message should strike fear in the hearts of corrupt politicians everywhere.

As if a timeless and timely new album and an award winning music video weren’t enough, I was triply astounded after watching the documentary Nobody Dies (available to stream Sat., Oct. 10), which follows Thao on a journey with her mom to Vietnam. The trip was Thao’s first visit to Vietnam, and her mom’s first time back since fleeing the country in 1973. It was a chance for Thao to see her mother in an environment where she wasn’t defined by being a refugee, as she often is in America. In both the documentary and the album, Thao paints a picture we don’t often see in American popular culture: the perspective of a child whose parents have lived through and escaped war.

Mossy: I watched your documentary, and it was such a beautiful tribute to your mom. Is there anything about your mother’s life and experiences that really stand out for you, that you think Americans could learn from?

TN: When I wrote Temple, it was because I wanted to offer a different narrative and rendering of someone who experienced war, and the idea of what a refugee is. And obviously in recent years, maybe throughout American history, how refugees have been reduced and the narrative that has been relayed. I think it’s really important to remember that there’s a distinction between an immigrant and a refugee. And also that someone is not just defined by this war that happened to them and their country. I think that’s why Temple was so important for me. I really wanted to capture my mom’s life before, after, and during; and just help enrich that community. I was raised in Virginia, and growing up, it was so stark the way people treated (refugees). I think that parents that are refugees or immigrants witness a lot of incredibly unfortunate encounters, where their dignity is dismissed. You watch your parents be dehumanized in either casual ways, or really serious ways. So this was one of my efforts to address and make peace with that.

Mossy: When I was watching your documentary I found myself smiling. And then I got to the story about your dad and I just started bawling. What parallels do you see between your father and the patriarchy at large?

TN: That’s an interesting question. My record before this one was about my dad. It’s called A Man Alive, and it’s just about our nonexistent relationship and all the bullshit. But what I started to understand when I was making that record, was just a facet of what it is to be emasculated in American society. And what that means for the families of the men who are emasculated. And I think that you see that a lot, especially in immigrant and refugee homes. And others, I mean, I’m only speaking from my experience. But what does a man do to assert power when he feels as though he’s denied power in society? I think it becomes a really personal and intimate, familial problem. And you know, it helps me understand his experience and what unresolved trauma that basically debilitates him, and renders him an irresponsible, reckless person. Patriarchy in general…I do think so much of it is people not knowing how to grapple with the expectations of masculinity. I could go on. (Laughs) I’ll just say it’s so detrimental in every direction, because if you’re not masculine enough, you will pay and then someone else will pay. And if you feel as though you’re not respected enough, then the ways that men feel pressured to illicit that respect in our society is so deadly.

Mossy: You said in the documentary that when you went back to Vietnam, it helped you understand your dad’s temperament. That you understood it…but you didn’t. It’s like saying, “I do understand where you’re coming from and I empathize, but I don’t accept how you’re treating me because of it.” Which I feel is kind of where true healing from trauma can begin. How else do you deal with trauma?

TN: Well there have been different waves of awareness and lack of awareness of what I needed to be doing. I mean, I’ve done the typical things like drinking. (Laughs) I think touring helped. I’ve spent the majority of my adult life on tour, and it’s a refuge. But it also allows you to not deal with anything for a really long time. You could go your whole life without dealing with things. Of course, songwriting and making music. And really wanting to go there lyrically by being more specific with lyrics. Okay, and then therapy. But as far as music is concerned, I think it’s been really helpful to have these songs and talk about them, even under the auspice of promotion. But it’s also just connecting with people and talking about the songs. These levels of vulnerability make for a lot more humane experience. When we play live shows , if people get a chance, they’ll come up and tell me what a song has meant. And it really is so heartening and gratifying, and part of the healing.

Mossy: So you’re saying drinking didn’t work?!

TN: (Laughs) I still do it, so I’m not saying it doesn’t. Just don’t go crazy!

Photo Credit: Shane McCauley

Mossy: You have such a wonderful vocabulary, so I’m guessing you like to read. Who are you favorite authors?

TN: Thanks for saying that. Writing and reading favorite authors are how I prepare the albums and the songs. And when I’m writing songs, I never listen to music, and I only read. But I love, oh man, I grew up reading Toni Morrison and her way with language and the vivid pictures she paints and the way she renders people. Grace Paley is another writer who’s style I love. Marilynne Robinson. George Saunders. I typically am drawn to contemporary literature. And now there’s a lot of reading to be done to learn about how America has become what it is. And to that end, Octavia Butler and James Baldwin really influenced the writing of this record.

Mossy: So you’re like Kurt Cobain over here, writing songs inspired by literature.

TN: (Laughs) I wish I had a cool sweater.

Mossy: Ah, he had the best sweaters.

TN: He had the best sweaters.

Mossy: I saw on your Instagram that you support women prisoners and Critical Resistance. Why are you specifically interested in these causes?

TN: With the California Coalition of Women Prisoners, I’ve been involved with them since 2013. Originally it was because a housemate of mine was an amazing organizer, and has been with them for years. And I was home from tour for awhile and he asked me to join this advocacy group, where we went in to prisons and visited, and we were part of a legal advocacy team. So the album, We the Common is entirely about and in tribute to these people who live inside, and this organization.

Mossy: Do you need to have a law degree to do that? I wanna do that!

TN: (Laughs) You totally can! No you don’t have to have a law degree. So the people like my friend…they don’t officially have a law degree. They just know so much about the system, because they’re constantly trying to help people figure out their parole, and how to get their face back in front of a judge. So we went in conjunction with a lawyer. We were just a team that was basically working with a pro-bono lawyer.

Mossy: You mentioned connection and live performance in your documentary. How do you think the musical performance landscape is going to change since the pandemic?

TN: I don’t know what’s going to happen to the venues as they exist now. I don’t know what kind of modifications or concessions they’ll have to make. So I do think that there will be more unconventional and nontraditional venues that come up by the time we’re ready for crowds to gather. And I think there will be more multi-use spaces and art institutions and contemporary art museums. More of those kind of hybrid events. I don’t know what’s going to happen in the rock clubs. It’s so sad. But I do think that we were barreling towards a reckoning. And I liken the music industry to the restaurant industry in a lot of ways…how thin the margin is for survival. And I think people will play smaller shows, because they can happen more quickly. And I think there’s going to be a lot more direct to fan engagement. And those who have a preexisting fan base will lean more into those fans, and be less concerned with expanding.

Mossy: It’s almost like what’s happening in the music industry is symbolic of what needs to happen everywhere. More localizing and community building.

TN: Totally. And I think Bandcamp is going to take an even stronger role as leaders of a more ethical model. I think what’s happening right now with streaming services is, ah, (laughs) unbearable.

Keep up with Thao’s music and the organizations she supports on Instagram at @thaogetstaydown Stream the documentary Nobody Dies this Saturday at https://www.youtube.com/user/thaomusic

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gettin’ Schooled by Gracie and Rachel

Sep 17, 2020

By Mossy Ross

Photo Credit: Tonje Thilesen

Gracie and Rachel are a finish-each-other’s-sentences, knows-what- the-other-is-thinking, musical soulmate, power duo. They are wise beyond their years, which is reflected in their music and in their conversation. They build each other up and seem to constantly strive to understand each other, so they can better understand themselves. Throughout our interview, they offered tidbits of honesty and advice and honestly, I could have talked to them for hours. And not just because it would have been cheaper than seeing a therapist (and probably with better results). They’re a team of soul-searching, wisdom-spewers who have a lot to say, and they’re saying it on their second album, “Hello Weakness, You Make Me Strong.”

Their new album out this Friday, reflects how life imitates art. And in their case, art imitates life. Their personal growth parallels their development as musicians. They show that beauty can be made, if we can come to terms with our own weaknesses. The two speak freely about addressing their shortcomings fearlessly and head on, and the result is an empowering and ageless album. Their recent video for “Underneath” shows how determined Gracie and Rachel are to be honest with themselves, even if it means making themselves vulnerable.

Mossy: Have you known each other a long time?

Gracie: We met in high school (in Berkeley, California). We were in a dance class together and were assigned to play music for the class. It was kind of an arranged marriage in that way. And then we went off to separate music schools for university, and then came back together to New York City and moved to Bushwick.

Mossy: So what were you like when you were younger, before you knew each other? What was your path like?

Rachel: My path was very serious, and exclusively tied to me, myself, and the violin. I hopped around between public schools, and then I went to a boarding school for two years before meeting Gracie. So I would say, for me, it was just being in this machine of classical music breeding. (Laughs)

Mossy: Was that something that you wanted to do, or you got pushed into doing, or both?

Rachel: I think it was a little bit of both. I feel like there were a lot of blinders up, because there wasn’t a lot of encouragement to explore other genres of music, or how you can use your skills as a classical violinist in alternative ways. I knew that I loved music, and I loved playing the violin and it was working for me, and I liked all that. But I wouldn’t say I always felt socially that comfortable, or like I integrated well or that we had similar interests. I had a lot of different interests in music, like contemporary classical music, and avant pop music. So meeting Gracie gave me this opportunity to explore those interests in a nonjudgmental environment.

Mossy: Yeah, sometimes you need that one musical soulmate for your whole world to change. What did you listen to growing up?

Rachel: Around the house I would listen to a lot of Cyndi Lauper, Elton John, Selena. I would do a dance hour with boom boxes and stuff. But in high school, I got into Regina Spektor, Emily Wells going into college. Artists that had a classical approach, but were flipping it and doing something a little different with it.

Gracie: I didn’t come from as strict of training as Rachel did, so I was really grateful to meet somebody who had that theoretical knowledge, and was just going to ground me a little bit. I was just sort of free form writing songs, and it was just really such a good challenge to meet somebody who needed to know what we’re gonna play and how. And it made me have to be a little bit more regimented and focused in that way. My father was a theater director, and he did avant garde opera music and New Age music. So I was around a lot of composers and people doing some experimental stuff that I think really excited me at a very young age. My dad got me into Erik Satie as a pianist when I was younger. And then I got into my own little singer songwriter world and found people like Fiona Apple that I really loved. And then thought, “Maybe I could do that, too.”

Mossy: I think your music is a really good amalgamation of all those influences. It’s really unique. I love the new album. It sounds to me like a coming of age sort of album. And I don’t mean that it sounds young. I mean, I’m forty and I think I just finished my coming of age album! But just in that it feels like there’s been a development in your lives. Is that true?

Gracie: Yeah. I think that the first record was really just us as a piano and violin duo. And we only integrated drums because the producer we were working with had a drum kit in his car that he needed to bring into our loft.

Rachel: Not even a kit, just one drum! (Laughs)

Gracie: Yeah! Just one drum. Which was a happy accident because it got us to play with the kick drum. Like it became an intentional thing, where it was a kick drum on it’s side, so it was like a timpani, like a classical drum. But they’d rock out on it, and we’d have our drummer there to complete the three piece. But the bones were just piano, violin, and drum. And there wasn’t a lot of other experimentations and using synthesizers and our vocals in different ways. Rachel has experimented so much more as a producer on this record. And I think a lot of it has been about our process of living together and working together, and how we communicate very differently personally and musically. We’re really quite opposite in a lot of ways, and I think that’s where this album started to make a lot of sense to us. In finding strength in those oppositions. Finding strength in our weaknesses, and in what the other person has that we don’t individually possess. So it feels coming of age in that regard.

Mossy: Can you think of a specific example when you realized your weakness makes you stronger?

Gracie: I think in a really basic way, maybe Rachel will find something more interesting to talk about (laughs), but I’m a lot chattier and confronting. And transparency is my favorite thing to, you know, flush out a problem when it happens. And Rachel is a little more guarded and patient and more like, “Let’s work through it maybe in this way first, or work through it on your own first.” And I need that immediate action. So I think really me learning that about her, and where that was useful, and vice versa.

Rachel: Yeah, I was gonna say it’s seeing that other person’s perceived weakness, and how it makes you stronger.

Gracie: Right. Like for Rachel it can be hard not to confront certain things, and for me it can be hard when I confront them too often. I can create problems in my mind by confronting issues that aren’t maybe there. So taking maybe what is Rachel’s weakness and using it as my strength, and my weakness as her strength.

Rachel: Like a reflection.

Gracie: And us just finding and really capitalizing on those oppositional forces between us, and finding gratitude for them. We can’t all be like one complete perfect person, and I think when we accept that and we dance with our weaknesses as a strength, it’s a really beautiful thing.

Photo Credit: Aysia Marotta

Mossy: Where do you think all of your wisdom and self-awareness comes from?

Gracie and Rachel: (Laughs)

Gracie: Socrates. I don’t know. I’m a really anxious person and sometimes a lot of these songs are written to myself, to just get out of my head and get into the big picture of calming down. I really can’t apply that wisdom very well a lot of the time. (Laughs) So writing these songs to my subconscious is kind of like a way of processing and helping me not judge myself. “When you don’t know, you know” is really powerful Socratic thinking. That we can’t have it all figured out and when we think that we do, that’s when we’re really not learning anything at all.

Rachel: Also, I would say sometimes I feel my weakness has been not being able to find my language tools effectively, articulate something, and translate myself in a productive way. So really where I find the way to translate myself the best is sonically. So this record was a great opportunity that I kind of lifted that up. And it’s okay that I don’t always have all the words. It’s okay that I still have a feeling, and I can put it down, and hopefully communicate through sound rather than through lyrics.

Gracie: I think just finding a perceived weakness of yours and not judging it, but exploring it and opening yourself to it can be just such a revolutionary act. When we have all of this self judgment, we are gonna have that out in the world, too. So I think owning some deficits that we each individually have, has been really helpful to our growth.

Mossy: What are some of the things that trigger anxiety for you?

Gracie: Pfffhhh…what doesn’t trigger anxiety? (Laughs) I think I’m an over-thinker, so I can create fear and worry around a scenario that I might have actually perpetuated just by thinking about it so much.

Rachel: I think we’re both people pleasers. We really like to make everybody feel really heard, and like we’re being respectful. And sometimes we forget to check in with how we’re feeling, and what we’re thinking.

Mossy: It seems like some of your songs touch on mental health. Is that something that’s big for you?

Rachel: We’re both in therapy. (Laughs)

Gracie: Yeah, I think we’re curious about talking about how to be gentle with ourselves. And hopefully that’s something that speaks to a broader issue around mental health. And just that when we aren’t gentle with ourselves, we can really create some huge roadblocks and pain for ourselves. So I think and hope the songs are speaking to a sort of forgiveness of the self.

Mossy: I read somewhere that you said the album made you have to ask each other some difficult questions when you were creating it. Can you talk about any of those?

Gracie: I think it comes back to communication in a lot of ways. Asking Rachel to call me out and come to me with stuff that was maybe not something she wanted to do. And her asking me to have patience with that.

Rachel: Yeah, not scrutinizing every little thing and seeing where it leads us, because maybe it doesn’t lead anywhere.

Gracie: Yeah, letting things roll of the shoulders. Something we were realizing is Rachel tends to judge her emotions and put them into boxes. And therefore if she can’t judge them…

Rachel: I’m just not gonna acknowledge them at all.

Gracie: And I judge my emotions with too much weight, I give them too much weight, where I need to actually compartmentalize them and put them in a box, and put them away. So I think it was asking each other how the other does that, because we do things so differently, and it gets us both into trouble.

Photo Credit: Tonje Thilesen

Mossy: Were there any specific defining experiences that inspired this album?

Rachel: Trusting ourselves, trusting each other.

Gracie: Yeah, trust. We had just come off a big, long tour. And our management told us, “Okay, when you get off this tour, you’re gonna go and you’re gonna write a record.” And I remember just feeling like it’s so bizarre to create art on demand, or on command. And there was a really big fear around that, because we’d been touring for the past couple of years and we were like, “Do we know how to write still?” Do we know how to do that when it’s not coming from an emotional reaction, or a response to a real life event? Like when we’re told to do something, are we gonna be able to do that? And there was a big concept of trust with each other and with ourselves, and we just had to lean into that and say, “Okay, ultimately we have to trust ourselves, and no one else.” And we just went for it. And we had to build that muscle, and it definitely took some time of just throwing stuff at the wall and seeing what landed. But we hadn’t really pushed ourselves to trust ourselves, and I think a lot of the songs are speaking to that and to process, and showing up to process, and not being afraid of it. We used to write so individually and then we would bring it to each other. And now it’s like we’re so much more comfortable, just from pushing ourselves to create on the spot. “Write ugly, edit pretty” has become a saying in our household. Just don’t worry about obsessing on it, and I think we apply that to a lot of things in our lives now. We need to just write ugly and edit pretty. Figure it out later, but trust your instincts.

Rachel: Like Patti Smith said, “Freedom is the right to say it wrong.”

Gracie: And then the Kavanaugh hearings. Christine Blasey Ford was giving her testimony when we were in the middle of writing this record. And we saw a lot of really empowering women and people coming forward with their stories, and so there was a big feeling of empowerment. We were finishing the song “Trust” during that time.

And we were like, this isn’t just about trusting our narcissistic fears about writing, it was about trusting ourselves to do something when it’s not always comfortable or easy. So we wrote a number of songs during that time. And we put one of them out that was about the hearings, just because it felt like we couldn’t wait another six months to make the record. We just wanted to have a conversation with people about it then. It’s really cool when you can talk about what’s happening right now, because so much of music culture is, you know, people were working on something for a year, and now the album’s coming out and they’re in a different place. Like, Rachel had more hair when we were making the first record. (Laughs)

Rachel: And also to use our art in that way is a great privilege. Follow Gracie and Rachel on IG @gracieandrachel

New album out Friday, September 18!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Talking Toxic Masculinity with CRICKETS

Sep 8, 2020

By Mossy Ross

From left to right: Roddy Bottum, JD Samson, and Michael O’Neal

Photo: AF Cortes

Each member of CRICKETS comes with a rich history of musical experience. One might think that with so many strong sonic personalities from such different backgrounds (Faith No More, Le Tigre, MEN), it would be nearly impossible to hone in on a sound that’s anything other than chaos and noise (with a bit of ego sprinkled throughout). But CRICKETS has managed to do the opposite. Instead of going the way of so many supergroups and pulling out all the stops, they’ve uh…pulled in all the stops. Continuously stripping down to a sound that is a pure expression of not only the sonic landscape they’re seeking, but their ethos as well. The result is music washed of all toxic masculinity, and what remains is only what’s necessary to express their intentions.

Mossy: How did you all start playing together?

JDS: I put out an Instagram story saying, “Anybody want to start a band?” Because I was kind of sick of making work on the computer, and then covering it for live. That’s what I had done with previous bands, so I was like, “Who wants to get into a room and play music together?” And Michael and Roddy and a few other people responded, and we just started meeting up once a week and jamming. And then other people had different priorities come up for them, and it ended up that Michael and Roddy and I were the people that kept coming back for more. I can’t remember when that started.

MO: 2018.

Mossy: How long were you writing and jamming before you actually started recording?

RB: The process was probably over a year. We started in a different formation, like JD said. We had a couple other people playing with us, too. And what we’ve done since we started, has just been this slow process of stripping things away. I don’t want to say in terms of the other people. But the process of the music evolved in a way where stuff kept leaving. And so we wrote songs and stuff, and it was kind of unconventional in the way we went about it. We just started taking things away from what we were doing. Stripping things down and become simpler and more sparse. And it took a year to kind of get our sound.

JDS: We went to Roddy’s friend’s house upstate in a place called Peekamoose, and I think that was kind of a really important moment for us. Because I remember this feeling of like, “Yeah, just let the guitar ring out over nothing for a second. That’s what this is!” And it was just this beautiful moment where we realized we wanted to, I don’t know, appreciate the space in between.

Mossy: I feel like the hardest thing for me about making music, is coming up with the sound you want. Do you all find that to be the same?

JDS: I think that…sorry if I keep talking, but…talking is fun. (Chuckles). But I think sometimes the computer and the opportunity to use many sounds is an obstacle. Because then you get confused about what you want to do. And I think that the beauty of this project was Roddy had his keyboard, and Michael had his guitar, and I had this one drum machine, and this mic with this one effect. And we just kind of jammed, and there was no way to do anything different than what we made. So we didn’t really have another option to question. I think our questioning was more around the idea of how other people would hear it. For me, at least. I was just, at times, confused or concerned that people wouldn’t get our intentions. But these guys are really good at helping me get through that.

Mossy: One thing that struck me is that you actually use the words “toxic masculinity” in a song. I would love to hear a defining moment for each of you, where you experienced that toxicity; and then, like you say in the song, realized it was something that was in you, that you could grow from?

Roddy: The toxicity that sort of creeps into the craft of songwriting is so many things, but for me…the abundance of options. There’s just so many things you can bring into the craft of what you do. And I’ve just learned over the course of time, to ignore all of the options, or just limit the options. And it’s the excess of the options and excess of bringing different elements in and in and in; like overdubs and overdubs, and adding and adding and adding, that’s just this pig-ish sort of behavior for me. And a good example of what I consider sort of a toxic masculine force that comes into the craft of songwriting or creating. I mean, it’s been the course of my whole life, it’s been a creating step.

I’ve always known in the back of my mind that less is more. But making a real decision to act on that, felt like a pivotal place for me. It’s like, I know that less is more, but even so…I do more. And I like things dense and more and more and more. And to sort of go away from that grain of thought was profound for me. And in CRICKETS, making that decision, talking about it, and stripping down in the way that we have, was really empowering in a political way.

JDS: Yeah, I think in the case of commenting on toxic masculinity, I think abstractly and conceptually without the lyrics, we still would have been doing that. And I think that particular song just also happened to reflect that content lyrically. So maybe it’s the song that tunes people into that conceptual experience. But yeah, I think a lot of the lyrics were written for a different purpose. I was working on a book. Actually the interesting part about it, is I’ve never been in a band where I jammed vocally with people in a room. It was always computer based. It was like, “Here’s this track. Sing something on it, bring it in, let’s workshop it, what are the lyrics, what’s this song about?” So this was the first time I was actually vulnerable vocally in that way. I think sometimes, you could call it a crutch, you could call it a beautiful collaboration of mediums, but I think I went to this writing I was doing to comfort me, so that I had something to say that felt already grounded, and it made me less fearful or vulnerable or scared to present something to the group.

Mossy: So you went to the book you had been writing?

JDS: Yeah, and to be honest, now I’m not writing that book. Because it felt like it was this therapy that brought me to the lyrics for this record.

Mossy: Michael, what about you? Any defining experiences with toxic masculinity?

MO: Yeah, it’s interesting, I think in the context of bands, it’s making me think of MEN, and that time of my life. I feel like I was a lot more insecure. And I feel like MEN was awesome, and there were so many great moments with it. But it had its toxicity, too, and frankly didn’t end on the best of notes. And that was sort of a mix of a lot of different things. I know for myself, I was wanting success, like, so bad, that I would be an asshole about things that I thought would equal success, or that I thought were right. I feel like, in bands, we can fight so hard for our opinions and our positions. So that often led to shit between JD and I and our other bandmates. So bringing it to CRICKETS, one of the best parts about this band, is JD and I have repaired that damage. We’ve learned how to be in a band together in a way where we always challenge ourselves when it comes to that toxicity, and with Roddy, too. I feel like we’re always trying so hard to be agreeable bandmates.

Mossy: Because you have the power “to heal and change and grow” (I’m quoting the lyrics to Elastic here)!

MO: Exactly! It’s exactly that within our band. I mean, I haven’t heard all the stories with Roddy and his previous bands. I mean, I’m sure you’ve got plenty! Faith No More, I mean…(laughs) Like times when you’re just an asshole to your bandmates, you know. So I feel like we all try to be really good to each other in this band, and come to democratic decisions.

Mossy: That’s one thing I love about getting older and being able to change, and then have people in your life that are willing to change as well. It makes things so much more cooperative.

RB: Yeah, and it’s such a good point. The communication part of it all. If we didn’t communicate well, it would be such a different organization, such a different band. But it’s so key just to be able to listen. I grew up with three sisters. In my life, with my family, it’s just been listening. And then you get into certain situations and it’s like, people don’t listen. But it’s so key to our equation and what we do together.

JDS: Yeah, our methodology is simplicity, in order to erase toxic masculinity. Both in our communication and in our instrumentation. So it all fits in together.

Mossy: Would you say being a good communicator is more of a female quality?

RB: I think for sure. And listening. It’s such a masculine thing to do, to overstep, and to talk over other people. I was watching that on the news yesterday. Kamala was talking to…I can’t remember who it was. But it was so cool to see Kamala Harris go, “I’m talking,” to the guy.

It’s such a guy thing. He wouldn’t stop. He just kept talking over her, because he’s accustomed to letting people allow that. People let him speak over them as a man. But to stop and listen is, for me, I don’t know, I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s a feminine thing, but it’s definitely not a masculine quality.

Photo: AF Cortes

Mossy: Have you heard of “toxic femininity?”

RB: (Chuckles) That’s a good question.

Mossy: I was just reading an article in Psychology Today about it. I’m paraphrasing, but it said that male toxicity is when a man behaves in a way that is damaging to himself, when he exhibits these overtly male qualities. And toxic femininity is when a woman acts in a way that is damaging to herself, in order to embrace femininity. One of the examples (of toxic femininity) in the article was how a woman will order a salad on a date even if she’s starving.

RB: Honestly, it’s hard for me to stretch and see examples of feminine toxicity. I couldn’t use toxic in that definition. That’s a really poignant and funny example, eating salad. (Laughs) Like just as a poetic example, that is far from toxic.

Mossy: I guess the “toxic” part of it is how a woman will allow herself to suffer in order to appear more feminine, and appeal to a male ideal. Like not saying “I’m talking” when someone is talking over her.

JD: I think that (calling it “toxic femininity) is like saying it’s reverse racism. I think it’s impossible. I hear where you’re coming from, and I’ve heard of feminine toxicity before, but it’s kind of impossible to, quote/unquote, “blame” a marginalized community for the toxicity of the patriarchy.

Mossy: Because would female toxicity exist without male toxicity?

JDS: Exactly. And that’s just my opinion. And to that point, I think it’s interesting because my persona has been this butch woman, and publicly, that is how people see me. And I think addressing that toxicity within a female masculine body is really important. And I think maybe that hasn’t been done that overtly, so I felt like it was really a responsibility of mine to say that out loud. So I think maybe this is a little bit more complex.

Mossy: What do you feel are some of your responsibilities?

JDS: Everything for me, gender wise, is very fluid. And I think we all inhabit these qualities that are masculine and feminine. And I think we all fall into this space of masculinity being equated with power, and those dynamics become entrenched in some of our relationships. Just because of our inherent understanding of confidence, and what it means to be in relation to other people, and how to maintain power in service of our desires. And I think sometimes that is toxic. And I think nobody is free from that experience. But I do think that, specifically in my case, both growing up with the media around me of toxic masculinity everywhere, and me seeing that in order for me to feel power or to feel confidence, I need to do x, y, and z; I did kind of create a roll for myself that was not only dangerous, at some points, but also oversexualized in some way. And I think this band was a way for me to get out of that experience of my, quote/unquote, “persona.”

Mossy: How did the name CRICKETS happen?

MO: I wanna tell this story! (Laughs) We were trying to come up with a band name, as most bands find is very, very difficult. So we had this text thread between the three of us, and we’re communicating about this or that. And every once in awhile someone would throw out a band name, and we’d see if it lands. And Roddy said something in the thread, and JD and I didn’t respond for a really long time. And his response to us was, “Crickets.” And we’re like, “That’s the band name! CRICKETS!” (Laughs)

Mossy: One of my favorite games to play is coming up with band names.

RB: Yeah, we had a running list. I have it somewhere written down. Dozens and dozens of names.

JDS: I really wanted Seltzer.

RB: I really liked The Inhalers.

Mossy: But don’t you think CRICKETS is a pretty good name, when you think about how your sound is just stripped down?

MO: Oh yeah, we even played one of our shows with a Youtube video of cricket sounds, that JD would pull up on her phone and play in the background the whole time. So in between songs, or in quiet moments of a song, all of a sudden you would hear the sound of crickets.

RB: I think the name works well. I think it’s one of our proudest achievements, is naming our band. It’s not, like, super on the nose. But it suggests really right where we are, I feel like.

Mossy: What is “Drilled Two Holes” about?

JDS: I did this project that was about drilling holes into stones. It was kind of questioning the identity of being stone. I wrote an essay and it was a sexual reference about the different holes in the body.

Mossy: What was the project with drilling holes into stone?

JDS: It’s kind of a long story, but my dad was a sanding gravel miner. So stones and rocks are a big part of my life. But also having this identity of stone, which is a historical lesbian identity of somebody that doesn’t allow other people to touch them sexually. And so I was kind of, no pun intended, digging into this idea of why that has been my identity. And it came about in relationship to writing this book, and thinking about my responsibility of healing toxic masculinity, basically. So this project was me drilling holes into hundreds of stones, and creating a suit out of them. And during the process, it was so monotonous and physical, that I experienced a lot of feelings around the memory of having sex with people throughout my life.

Photo: AF Cortes

Mossy: How do you see the “American Dream” being revised, now that we’re discovering our values have been influenced so much by the patriarchy?

JD: Well, I think more specifically, within the music industry, there are some issues of pretending you have more money than you do. And also just this farce that people who are famous have money. Myyki Blanco just posted something relevant to this conversation a few weeks ago. And I felt like this was an interesting next step of the idea, that more popular/famous/renowned artists are still using wealth as a part of their image, and maybe this is something to discuss when thinking about how much money musicians are getting for streaming. It is just so clear right now with Spotify, if you have 250 streams, you get like, less than a dollar or something. And I think it’s relevant in the sense that, as musicians, we can’t support ourselves from just making music. So that’s something I’ve been thinking about recently, is new ways of thinking about the streaming industry and digital distribution.

Mossy: Any brilliant ideas yet?

JDS: I’m on a steering committee for a project right now called Ampled. It’s kind of similar to Patreon. But there’s a lot of organizations, companies, and co-ops starting where people are just rethinking. And I think Bandcamp has done such a great job this year of centering the artist and their needs, and particularly centering movements like Black Lives Matter, so they can be aligned politically with what the artists all want. We put something out on Bandcamp, and I know Roddy has a project on Bandcamp he’s been doing, too. Mossy: What’s the other project you’re working on, Roddy?

RB: I just started something a few weeks ago that’s like a daily music share, just to sort of keep me busy and to work on my craft. I go back and forth with it because it seems like a little bit indulgent of an expression. But I think the craft of what we do, writing, music, whatever you do…I think the craft often gets overlooked. So I just got this notion a few weeks ago, that to work on that craft on a daily basis is really, really important. Especially in times like this. Not that everybody has a lot of time, but people have a lot more time right now. It just seems pertinent to address the craft of what we do, and to become better at what we do. So I just started this process of doing a daily music share. So it’s sharing a piece of music every day, and every day I have to finish it. It’s helping me get to where I’d like to be as an artist in a quicker way. The music is free, but any donations people make goes to The Okra Project, which is an awesome organization that feeds black trans people who need food.

Mossy: You’ve made it a point to make sure your music is political, which I think is a vital component of making any sort of art.

JDS: Yeah, I think there’s been some really interesting conversations throughout COVID about the purpose of making music right now. And I think (the conversations are happening) for a lot of reasons, but mostly because you can’t tour and make money that way. It’s like, people are forced to kind of consider what the model of the future of the music industry is. Holly Herndon posted something really interesting the other day about just experimentation music. And like Roddy said, for CRICKETS in general, the ethos is, we’re trying something out, and we’re just making work. Why does it have to be completely 100% perfect, and factory made for it to succeed? Why can’t the experience and the process of making it be enough? And why can’t this music be just for our community, and just ourselves, and just for the people who want to listen to it, and not try to fucking get the world to be obsessed with it? Because it’s really just about our process.

MO: Yeah, you mentioned the American Dream earlier, and I think what’s interesting is the American Dream is what instills in us, that we have to be famous in order to be successful. And that’s what leads to this toxic place. And that’s what’s so fucked about the capitalist way, is we push everybody aside and just start tearing shit down just to be, quote/unquote, “successful.” So I really hope the American Dream shifts so that we can all understand a different kind of success or dream.

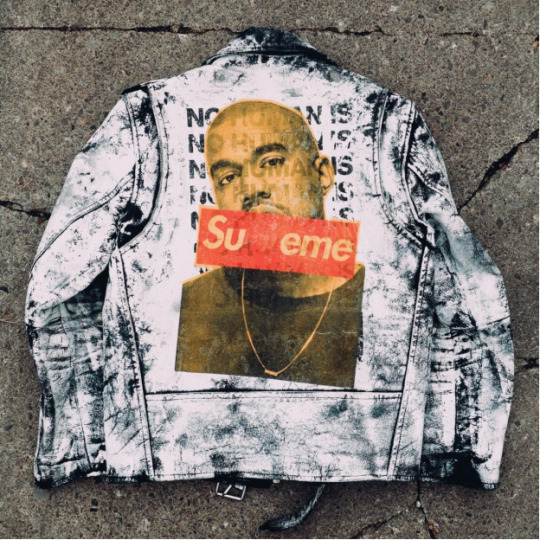

JDS: Celebrity culture got us to where we are right now with the president that we have. What’s the most punk thing we could do right now? Fucking kill celebrity culture.

RB: Yeah, the way we grew up, we looked at these images of opulence. That’s what we’ve seen for so long, like “Oh, shiny, flashy expensive.” It’s such a lazy approach to make things attractive in an expensive looking way. I just think it’s lazy and boring. There are so many more eccentricities to accentuate in a presentational way, rather than gold and glitz and glamour. That trend needs to end.

Watch the video for “Elastic:” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3y17lNE_gQM

Follow on IG @thesoundofcrickets

Web: www.thesoundofcrickets.org

0 notes

Text

Going Down the Rabbit Hole with Wes Watkins

Aug 25, 2020

By Mossy Ross

Photo: Bohemian Foundation

Wes Watkins has seen it all. From living on the streets and sleeping on trains, to touring the world with bands like Air Dubai or Nathaniel Rateliff and the Night Sweats; Wes has earned his stripes as an authority on life experience. So I thought it would be more insightful to use his own words to introduce our interview, by sharing what he wrote on Bandcamp to release his latest EP:

“I share this rushed album in hope that it reaches you in a place of good health, curiosity, and motivation.

I do not think that I, by any means, have all the answers.

I do believe that if we were more diligent in our pursuit of the actuality of our country’s history we would find our generation more prepared to underpin the greater good in the days to come.

I believe that we have been subject to the bigoted representation of an individual’s worth by our racist country and most are unaware that they are even effected by the indoctrination.

I believe that we all have our own bias and true change starts with an individual.

I believe that when that individual can truly hold themselves accountable for their daily actions, words, or thoughts; then they can begin to truly hold their community accountable as well.

I believe when that community can truly hold themselves accountable for their daily actions, words, or thoughts; then they can begin to truly hold their communities accountable.

And the fight grows and goes on.

So I share this album to make, at least, the beginning of the painful process of unveiling the true chronicles of our country a little more sufferable.

I have included some very basic, Wikipedia, links to get everyone started on their voyage.

Stay healthy, Stay empowered, Stay informed, Stay curious.”

In keeping with Wes’s advice to stay curious and research, you can click on the bold faced words to learn more about the people, places, and political and historical events he references. You can click on each one, and go down a rabbit hole of enlightenment. According to Wes, information is our biggest ally in the fight towards a more equitable society. Here’s a chance to arm ourselves with knowledge. Mossy: Are you originally from Denver?

WW: Yeah, believe it or not.

Mossy: Why is that unbelievable?

WW: Well, because Denver is super segregated. Aurora’s a pretty integrated city. But I think being black and from Denver, not just, like, living in Denver, is kind of like being black and from Seattle.

Mossy: Gotcha. So what was growing up in Denver like? I’m guessing, based on the sound of your new album, that you grew up going to church.

WW: Yeah, I grew up in the church. My parents were like, “You are not listening to mainstream music.” So I could listen to oldies, and I was in the church, and I started playing trumpet when I was twelve. I was playing keys and singing before then. And then when I was seventeen, my parents got a messy divorce, and I ended up homeless. And I like to say I’d been playing trumpet, at that point, for six years. But when I really started playing trumpet, was when I was homeless. I used to meet all these old cats who were like, “Ah, you don’t know what you’re doin.’ Do this, do this.” And then when a buddy got back from college, all of a sudden I was in one band, and then I was in, like, a bajillion bands. And that brings us to here. And now I’m not in any bands. I quit all of that and started my own.

Photo: George Blosser

Mossy: How did you end up homeless from your parents’ divorce?

WW: My mother went to a shelter, and since I was turning eighteen the next week, I couldn’t go with her. And since a restraining order was filed against my father, I couldn’t go with him. I was a minor when the restraining order was filed.

Mossy: How long were you homeless?

WW: Few years. Three years-ish. I think by 2009, I was finally on a lease.

Mossy: Did you ever live in a shelter?

WW: I went to a shelter, but I bailed out of the shelter pretty quickly. Cus shelters are messed up, man. There’s cats who are workin’ the shelter dealing drugs. It’s just another system that is really poorly designed. So it’s not helping these cats who are stuck in these situations at all, really. I would buy a cup of coffee and sit in the coffee shop all night, and then I would buy a round trip ticket on our light rail, and just sleep on the light rail in the morning, and then go and play trumpets on the streets all day.

Mossy: So something I liked about your album besides just the music alone, was what you wrote about it on Bandcamp. History seems to be such a strong focal point for you. It seems like when history is taught in schools, it’s more for reading comprehension. You just read the chapter and answer the questions at the end. There’s rarely any context, or explanation for why things that happened in the past, are still affecting what’s happening now today. You have speech excerpts by James Baldwin, Malcolm X, Nina Simone…these important historical figures. Clearly it’s important to you for people to hear those voices. How do you think knowing history can help end the systemic racism in this country?

WW: Well first off, I’m actually a high school teacher now.

Mossy: Oh shit! What do you teach?

WW: I teach audio production at alternative high schools. But you know, I don’t believe in history. I say that a lot, I talk about history a lot. History’s just weird because whoever wrote the history, that’s what we’re hearing. The winning side gets to write history. What I really believe in is chronicles. Because a chronicle is a factual account of history. There’s no, “We won, so it was like this!” Look, the last civil rights movement was fourteen years long, and it never stopped. I think that now what I find, is what we’re teaching our kids is kind of this weird experience of, “Martin Luther King was like this, glorious god.” And it’s like, no, Martin Luther King was a chauvinist. He was a sex addict and he really struggled. But in the same regard, he did amazing things. If we were doing a better job of just saying, “This is what happened,” and letting people assess for themselves, I think that we could teach empathy. And I think if people were empathetic to how our world is working, then all of a sudden we don’t have racism. Racism exists because people don’t have the empathy. They don’t understand how to put themselves in somebody else’s shoes. And I don’t think we can actually put ourselves in somebody else’s shoes, but you can try. And that’s empathy. I don’t wanna have sympathy for anybody, I just want everybody to have a little bit of empathy. And I think there’s a reason that you have cats like King and Simone and Fred Hampton, Huey P. (Newton), Muhammad Ali, all these cats…they’ve been sayin’ the same thing. I wrote songs ten years ago that I can go and play at a show, that will still have valid content today. And that’s because nobody got the empathy tip.

Mossy: Yeah, history definitely helps teach empathy. But also critical thinking and curiosity. What you said about Martin Luther King, I mean, in some religious and/or racist communities, every great thing Martin Luther King did, is discredited because he cheated on his wife. And so, you have these pious, religious people saying that anything this man said about treating people like human beings, is completely null and void. Because he had his own issues. I mean, sex addiction is a real psychological problem. It doesn’t discredit everything you do. It just means you need help. It doesn’t mean you’re not a sensitive, intelligent person. If that was the case, we wouldn’t be able to like a lot of artists. Jackson Pollack or Michael Jackson.

WW: Yeah! I mean, people are still buying Kanye records! (Laughs) Why!? Have you ever heard the name Glenn E. Smiley?

Mossy: No.

WW: Glenn E. Smiley is an interesting character that’s been erased from American history. When they started COINTELPRO, number one on that list was King. Number two on that list was a white man by the name of Glenn E. Smiley. Glenn E. Smiley studied Gandhian ideals. He’s who’s credited for teaching King peaceful protest. And so it’s like a weird thing where it’s like, why don’t we know who Glenn E. Smiley is? Why don’t white people know who Glenn E. Smiley is? Well, our government didn’t want them to know that there was a big, white ally character doing all of that. But Gandhi also… Gandhi was a racist! He hated black people. But still, there’s great things. You have to be able to see through that. Like you said, critical thinking. They don’t want us to critically think. That’s why we don’t get history.

Mossy: How did you hear about Glenn E. Smiley?

WW: Well, because I realized that before the last civil rights movement, a few interesting things happened. The Depression happened, then the New Deal happened, and even if there still was just a giant wage disparity, you could still get a job. People had jobs. You had educated black people who went to school for things like Civics. And we don’t have that now because they worked real hard to make sure we didn’t have that again, because they didn’t want a Black Messiah. And so, I realized, that we’re not prepared. I don’t think our generation is prepared for the civil rights movement, so I just think we should all be researching. I think we should be figuring out what the fight has been thus far. If we know what the fight has been, then we don’t have to keep fighting the same fight. We can say, “No! You said this fight was over for this, this, and this. And now we’re picking up the fight here.” We don’t need to try and redo everything that already happened. It already happened. And there’s been legislation that passed. We gotta put that legislation back in place. So yeah, I just started researching and I just found Glenn E. Smiley on Wikipedia.

Mossy: Yeah, Wikipedia and Snopes are your friends. You mentioned Fred Hampton before. He was shot in his sleep, and now we’re seeing that again just this year with Breanna Taylor. It’s like you said, we keep fighting over the same things. What do you think is the first thing people could do to take a step towards not being racist?

WW: I think it’s not just a first step, I think it’s every step. You have to ask “why?” We have all the options to learn the information. Black people didn’t create race. White people created race. Which is the weirdest thing. When I go down the rabbit hole, what I always get stuck on is, I don’t know why people are afraid. I think that there’s implicit bias towards a situation. I think true change is going to start with the individual dealing with that bias. I deal with my bias. I just retook all the Harvard bias exams. And I got that I had a strong bias towards trans people. And it’s something I talk about pretty publicly.