Text

BLOG 11

Comment on Reading Surveillance cinema. New York: New York University Press, 2015 by Catherine Zimmer (2015)

The aesthetics of torture in pop culture became more and more present. Since the end of the 1990s, there was an increase in the narratives giving a focus to the technologies of surveillance. Technologies for surveillance have frequently appeared in horror films as plot elements, and have often been associated to the killer's pathological desire to kill. However, in particular, the postmillennial horror subgenre of “torture porn” is closely linked to the use of video surveillance in more recent narratives cinema, to the point that surveillance and cinema became to structure one another.

Shortly after 9\11 attacks, President George W. Bush authorized the CIA to detain suspected terrorists and launched the so-called “war on terror” . In tandem with this, the Patriot Act was passed and signed into law by Bush in October 2001 – which was a US legislation in response to the Twin Towers' attack – significantly expanding the search and surveillance powers of law enforcement and the CIA. The "war on terror" and the Patriot Act gave the US government the power to spy on citizens with the justification of national security.

The genre of "surveillance cinema" both in European cinema and in Hollywood raises and performs this ideological war. C. Zimmer focuses on the series of movies Saw, in which some of the victims "learn" crime from the killer: they learn to kill, as they learn that moral stance deemed as normal. Ultimately, systemic violence got normalized both morally and visually. The postmillennial torture finds it expression in the porn genre, with the use of video surveillance in the cinema narratives. From the lone psychopath's perversion and pathology, there is a shift to the exercise of systematic violence connected to surveillance. Systematic violence got embraced in global culture as this visual language was naturalized and legitimized.

It is possible to read Saw using Giorgio Agamben's concepts of 'State of exception', 'zones of indistinction', and 'Bare life'. The ‘State of exception’ is the extralegal exercise of surveillance, detention and torture performed by democratic countries, or neo-liberal democracies, in which rules of law are temporarily suspended. Specifically, the laws protecting citizens against State’s violence are put in hold, and the law does not apply for some categories of people. The "zones of indistinction" are the spatial manifestations of state of exception, representing the areas in which state of exception is implemented. People living in a state of exception have no political status, and are reduced to 'bare life', meaning life in general, with no political or legal rights, without human dignity. The value of systems of Jigsaw – the killer in Saw – stands for a system that claims the right to decide which life is worth living, and whose rights have to be respected. Jigsaw represents the manifestation of sovereign power, and his games can be seen as zones of indistinction through which Jigsaw reduces his victims as bare life.

All the victims are chosen by Jigsaw because he deems them to be abusing their own lives or others' lives. In this way, the narrative of Saw provides the moral justification for all the killings in the movie. These moralizing mechanism creates a constant reference to the framing device of Jigsaw’s values. For the audience and the characters it is difficult to tell who is a victim and who the perpetrator, blurring the line between innocent/guilty. In this regard, it is relevant to link this to US' "war on terror" for normalizing and justifying torture because the victims in Abu Ghraib were labelled as different, for Abu Ghraib's pictures attempted to depict Arab detainees as deviant, in order to find a justification to the violations.

"Death trap … a victim in Jigsaw. Photograph: Allstar/Lionsgate" The Guardian

"Shawnee Smith was the first victim of the heinous Reverse Bear Trap in the original 'Saw.' " Greg Gayne, Lionsgate.

Jonathan Luke Austin wrote the article entitled “The Plasma of Violence: Towards a Preventive Medicine for Political Evil.” for the Review of International Studies (published online by Cambridge University Press in 2022). The author elaborates on how the historical accumulation of popular cultural, technological and textual items have become integrated with violent practices. J. L. Austin emphasizes how preconscious knowledge about violence is available to everyone, circulating outside of the official domains usually connected with it, such as the military. Interviews with Syrian torturers are among the empirical examples of the use of torture that are provided in this essay. When interviewed, many of these people, when asked about the ways in which they "learned" to torture, quoted movies from this genre like Saw.

This suggests that the way in which global culture circulates certain images of violence is really pervasive. Each person is so exposed to this kind of content in the field of entertainment that torture becomes normalized, as we familiarize with the language of torture. Violent content has always been there in the cinema, but never so easily accessible as today, even more thanks to streaming platforms as Netflix. These digital platforms allow people to enjoy horror TV series showing violence and torture from the comfort of their living rooms' sofas. Furthermore, Netflix series such as The Walking Dead can gain extreme popularity in a short period of time. When a series becomes popular among young people, becoming almost a phenomenon, bits of the scenes can be found on Instagram's reels and on Tik Tok, further broadening their visibility, and ultimately their normalization.

0 notes

Text

BLOG 10

Comment on Readings: Emily Regan Wills 'Alan Kurdi's body on the shore' in Baer, Hennefeld, Horak and Iversen (2019) 'Unwatchable' and Enrico De Angelis – 'The Controversial Archive: Negotiating Horror Images in Syria' in Della Ratta, Dickinson, Haugbolle (2019)

The news of the chemical attack in Khan Shaykhoun sparked strong international response: in retaliation, the US navy bombed a Syrian military airport some days later. President Donald Trump mentioned that the photographs of ‘poor children’ were the primary trigger for the attack. The story of Khan Shaykhoun, Adham al-Hussein, and Smart News well reported by E. De Angelis in 'The Controversial Archive: Negotiating Horror Images in Syria' is a clear example of the context in which are produced "horror images" showing violence against people in Syria.

A small part of the material arrives to international media, whereas most of it circulates on the Internet. These are called "orphan images", as if they have no parents or background, or better they so, but it is unknown because throughout the process, the photographer's name, the name of the victims are lost. These images circulating alone without captions or references are even more easy to be subject of exploitation and manipulation . The question of who were the photographed persons, who is the photographer, and under which conditions did they take the photographs are disregarded, resulting in the production of a mere image becoming to symbolize a war crime, which may give rise to international intervention. An orphan image reduces the victim to being just a symbol of any victim.

This gave raise to a debate on how to handle images portraying violent content among Syrian civil society figures and groups: some of them criticize the victims' exposure for strategic and ethical motives, even asking to cease publishing them, as they take away their dignity from the victims, and do not spark international solidarity. Two sides to the issue can be identified: one emphasizes the importance of the respect for the victim's dignity, and the other focuses on denouncing the situation to lead to action.

In September 2015, Alan Kurdi, a Syrian Kurdish child, who died while crossing the Mediterranean from Turkey to Greek islands. Alan’s body on the shore of Bodrum was spotted and photographed by Nilüfer Demir, first lying on the sand as if sleeping, and tcradled in the arms of a Turkish policeman. The first image quickly spread on the web, and newspapers debated whether to print them or not. This is an example of the political consequences that a horror photograph can have, as it was followed by Germany's decision to accept 1 million refugees that year, Swedish decision to accept over 150,000. Moreover, in Canada it contributed to shift public opinion, leading to a massive increase in private refugee sponsorship. At times, "humane insight" opens the possibility for political action, as it was the case for many with the photo of Kurdi, which made Syrian refugees seen, became human, bringing to a change in the world's action.

This raises the question of whether we should distribute pictures of horror or not. Western photographic norms consider photographing dead individuals as violations of the victims' and their relatives' privacy. There is a double standard because for example photographs of victims of terrorist attacks in North America and Europe are almost never published in the name of the principle of dignity found in the charters of journalistic ethics of media. While Western media is not showing pictures of corpses of casualties – such as American casualties in the Iraqi war which were hidden by the American government – in the Arab world, photographs of corpses of people killed in conflict are shown as martyrs to make a political statement about those accountable for those deaths. In defiance of the Western governments, ISIS released images of Westerners victims, following the deadliest attack carried out at the Bataclan in Paris.

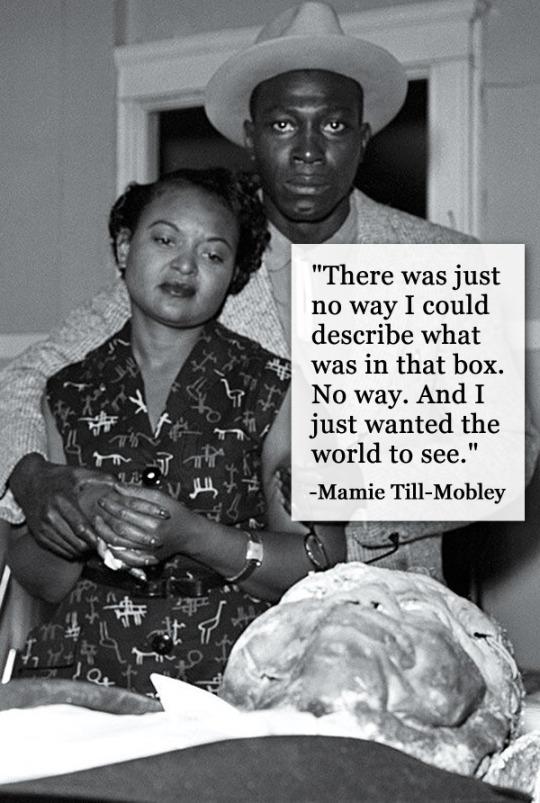

The latter one can be seen in the the case of Emmett Till – a 14-year-old Black teenager who was abducted, beaten, and lynched by two white men in 1955 in Mississippi. His mother decided to allow to photograph the dead body with her standing behind him, and pictures of the barely recognizable corpse were printed in influential Black magazines to denounce what was done to the son. Till’s murder and the photographs that circulated changed the civil rights movement.

Since it escalated into conflict, the Syrian uprising has been one of the most documented international events, contributing to the formation of what the De Angelis calls a "controversial archive”: the archive of horror pictures that has been put into question even by its producers and consumers, such as Syrian journalists and activists.

There has been negotiations around this controversial archive in the Syrian public sphere following the 2011 uprising. This negotiation involves both the public discussions, but also the individual approach to these images: if to look at them, share them or not, how to comment them. For example, on social medias, in particular on Instagram, it can be noticed that there is usually a period of mass coverage on an event that has just happened, full of people posting screenshots or reposting posts, and then the week later nobody is talking about it anymore on that platform. We should really question the impact that these practices can have. This lead to a debate denouncing the flaws of the ‘field of vision’ characterizing how most horror images are produced, looked, and circulated. The discussions around these images are referred by the author as ‘archival work’ aiming at negotiating collectively what should be remembered and in what way of these events. If the goal of the archive’s production is creating visual narratives able to change the conflict's course based on political interests, that is clearly problematic. On the other hand, the negotiation of horror images can be useful to develop "strategies of resistance against the dominant field of vision", creating alternative approaches to horror images both individually and collectively, especially aiming at identifying a more respectful status for the image, taking in consideration also the relation photographer–photographed, and the one with the viewer.

Although every individual has a personal approach to images which depends on their past and current life experiences, dealing with the controversial archive we can identify different ‘interpretive communities' who discuss the status of horror images and the practices concerning them. On the one side, there are ‘image-savvy communities’ made of individuals with more years of experience in cultural production, engaging in a critical approach to images. They question the strategic validity of the uncritical exposition of Syrian pain. On the other hand, the ‘unknown photographers’ – as their names are lesser known or disappear in the flows of news – young activists and journalists living in the country, producing the majority of the content of controversial archive. However, a moral issue connects the communities: the point that looking at horror images is a "moral obligation": the duty to at least stare at the conditions under which the fellow citizens are living. The two communities are tied by a complex relationship: anyone engaged in some way in the cultural production about Syria, necessarily has to rely on the controversial archive. Ultimately, criticism of the archive and its rejection are possible because just because of the archive's existence. The presence of those images is what allows to identify the problematic downsides of the field of vision, and exploring alternative new types of narratives. Enrico De Angelis illustrates how various approaches to the 'controversial archive' can shape alternative forms of resistance against the ruling field of vision.

The debate among Syrians on horror images can be interpreted through what Ariella Azoulay calls the ‘civil contract of photography', an unspoken agreement between those involved in the act of photographing: namely, photographer, photographed, and public. In A. Azoulay's view, photographs are powerful tools that can expose violations perpetrated by human violence or natural disasters against the photographed persons’ citizenship, and how they are not granted the same rights as others.

Nevertheless, the civil contract of photography shall imply the establishment of a certain "field of vision", which is similar to the "moral obligation" which the two ‘interpretive communities' mentioned above had in common. The viewer has to stare at the photo with a big responsibility, becoming an active participant in the act of photography through 'cinematic watching'. As Nicholas Mirzoeff puts it, pictures never speak for themselves. So, since pictures do not disclose anything in themselves, cinematic watching is key to avoid reducing images to merely what is immediately visible, and reducing the photographed people to the meaning that "ruling systems of vision" attempt to impose. In this regards, noteworthy of mention is the following quote from Syrian video journalist and trainer Maya Abyad – "I look at them because I think it is the bare minimum responsibility we have to undertake. We are not being subjected to the same level of violence. And we are hiding way too much in our bubble if we refuse even to see it".

It all depends on the way in which one looks and interact with the pictures of violence. One should stare at the "images of horror", taking some time to pause and reflect on the real context they are depicting, and the serious violations on individuals. Perhaps an approach like this is more useful to avoid the "anesthetizing" issue of trivializing the horror. We have to duty to be aware of the real implications of what is portrayed in photographs, as well as being conscious of the use we do of those pictures, as well as of the impact the sharing the image might have.

0 notes

Text

BLOG 9

Comment on Readings: Introduction from 'Investigative Aesthetics' by Fuller and Weizman (2021) and Paolo Cirio's essay on “Evidentiary Realism”

Proofs of suffering and destruction are modes of “erasure” and of aesthetic registration at the same time. Traces can be read and interpreted both with the aim of perpetrating further violence, or for contrasting violence. Besides, visual content sometimes cannot be accessed easily, or the images are blurred. However, the ones who want to perpetrate further violence often have access to higher quality means, such as satellites, drones cameras and planes, or the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for better interpretations. These people try to impose on those directly experiencing violence a unique narrative presented as true information. Investigative aesthetics questions mainstream institutions of authority, by proposing an alternative set of practices.

Before, images produced with Artificial Intelligence were not exactly realistic. For instance, they managed to depict faces very well, but not fingers. Then, AI trained on dataset based on the users' posts, and learned better to recognize and reproduce humans' traits. The latest images produced with AI – as the one showed above – are becoming more and more realistic, to the point that the viewer is unable to determine whether they are real pictures or not. These are "synthetic images", meaning that they have no ontological, physical, and material existence. The implications of synthetic images are that they can be used to create narratives that are not only misleading, but that do not exist at all. For instance, it is sufficient to think of creating a picture of a protest, which could start a movement, or an image presented as evidence to support a conspiracy theory, even the image of a fake killing, which could potentially trigger the start of a war between countries.

This raises the question of what constitutes evidence in the age of AI. Today, even when real digital evidence of the killing of people is present, the lines between the factual and the fictional are still deemed to be blurred by someone who claims that it never happened. In the "post-truth" period, reality is contested by authoritarian voices, which allays the public's worry about reality's reemergence. However, as Susan Sontag puts it :"Real wars are not metaphors" (Sontag), nor they are made by the media, but they are made of real bodies and blood. Nevertheless, as Trevor Paglen states, “wars are being waged through systems that are simply postvisual [...], systems whose imaging capacities exceed those of human eyes to the point of being invisible to them". Visual culture nowadays is mainly made of non-visuals and non-humans. There is someone that is post-human involved in the making of war that participates and consumes visual culture. While machines and metadata see everything, through body cameras, surveillance cameras etc., we as human cannot see what machines see. More importantly, human eyes cannot read and watch news 24h/24 as machines. There was an expansion of ways of seeing that paradoxically made us often unable to see. Nowadays, we are used to see human rights' violations on the screens all the time; thus, we become in a way anesthetized to social injustices, leading some to think that an event or crime did not really happen. Our reality of the 21st century is made also of non-human systems and the first step is realizing that there is something hidden to us, out of sight.

Artist and activist Paolo Cirio, in his essay "Evidentiary Realism" proposes a new approach to evidence. Cirio is committed politically to different issues, and his art is a combination of different disciplines. In the age of digital virtual media, some people argue that reality does not count; it seems like it is all about fiction. Karl Rove – an American Republican consultant who was Senior Advisor and Deputy Chief of Staff during Bush administration – once said "We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality". However, it is not as simple as that.

Historical realism in art traces back to France in

the aftermath of the 19th century revolutions, when artists

refused Romanticism for realist portrays of political turmoil and famine. Indeed, this pattern of aesthetics alternated the priority of the social over the personal, which came back during the 1930s and the post-war period. There were two tendencies in the West: the first is "Art for Art's sake" – realist art finding inspiration and attempting to represent reality as it is – thus, prioritizing the subjective over the political. Secondly, realism politically engaged, becoming a way to denounce social and political injustices, prioritizing the political over the personal. With the beginning of the 21st century, the social realm and its representations were once again brought to the center of social inquiry. Realism depicts the social oppression, showing the situations in a true and accurate way. In this sense, 9/11 attacks were an awakening call, and it is in their aftermath that can be identified the return to reality in art.

Today, realism in art is enhanced by advancing technology, enabling artists to capture and access reality as never before. Enhanced realism can be conceptualized as "forensic information". Realism is out of sight in the sense that the characteristics of today's social context are indecipherable at first, but we see the dreadful consequences. Cirio argues that realism should return through the intersection of documentary, forensic and investigative practices used by contemporary realist artists to bring to surface the hidden unseeable by society. Jack Burnham and Hans Haacke argued that "If you make protest paintings you are likely to stay below the sophistication of the apparatus.” Old-school artists cannot exist anymore because we can no longer understand reality merely through paintings. Cirio calls for the need of interdisciplinarity, such as by creating a team as in forensic architecture. Forensics architecture includes also open source investigations, digital modelling and crowdsourced investigations. Forensic architecture employs technology, while also questioning the problems and politics of the technology used. Forensic architecture combines elements that were already in the public domain which could have been seen by us, but perhaps we failed to see the relationship among them. Artists committed to realism should team up with architecture to try to understand the complexity of reality. Evidentiary Realism examines the tools, the economic, political, legal, cultural structures interconnected used to bring reality in its complexity to surface. The urge to piece together pieces of our complicated world is what drives evidentiary realist artists to present evidence. And in doing so, it is work consistent with the original history of realism and documentary approaches.

Artists investigate and represent reality through a wide range of materials and techniques; for example, through crowdsourcing evidence which expands the venue for the legitimization of evidence. But, is this art or evidence? Some lawyers and arts critics – feeling threatened by it – argue that it is "art, not evidence", while other art reviews consider it "evidence, not art". Ultimately, it is both. The two work of art and work of investigation do not have to be seen as opposites. Aesthetics and investigation can work together to take reciprocally potential out of each other. Although the fields of aesthetics and imagination are seen to be distant and at odds with the world of investigation, they are in reality fundamental to it today. It is no longer possible to just investigate facts in the proper sense as before. There is the need of imaginaries that can function both within and outside of disciplinary frameworks.

The outcome of investigatory art is a clear message. This kind of investigations are art used to inspire other institutions, and raise awareness on particular issues, which is needed in realism. Fuller and Weizman support the aesthetic practice of investigations combining different elements to form collective ones, called "investigative commons" based on various perspectives, as opposed to the expert-mode knowledge in which everyone relies just on the words of an individual, in which allegedly lies knowledge.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BLOG 8

COMMENT ON Rebecca Stein's "'The Boy Who Wasn’t Really Killed': Israeli State Violence in the Age of the Smartphone Witness".

While before the role of the bystander was merely to witnesses through sight and presence, with the proliferation of light cameras there was also the proliferation of subjects who were allowed, or took the right, to film. As Susan Schuppli puts it, there is a shift going on for which the human witness is being substituted more and more by a range of material witnesses due to technology, especially drones and body cameras. Nowadays, not only the human bear witness, but also non-human subjects, such as surveillance cameras.

Forensic Architecture is a research agency founded by a radical Israeli scholar Eyal Weizman at Goldsmiths University of London. The team carry out the so-called open sourced investigations, which are visual investigations collecting proofs to investigate the state's human rights violations and environmental destruction. Digital forensics include open source investigations, digital modelling and crowdsourced investigations. Crowdsource implies verifying the information using what is available on the internet, and put the information together. Many digital forensics emerged during the Arab Spring, beginning in 2010 and 2011, the wave of pro-democracy demonstrations and uprisings which took place in the Middle East and North Africa, that challenged some of the region's enduring

authoritarian regimes.

The group of people working in the Forensic Architecture are skilled in aesthetics, as it includes architects, filmmakers, investigative journalists, and artists. From the field of evidence to denounce human rights violations, there was a shift towards the field of aesthetics, which more people can understand. There has been a decontextualization of some of these images, as they started to feature some of the content in "glamorous" places, such as in the international cultural exhibition Venice Biennale (la Biennale di Venezia). Therefore, they are aware that the main focus now is aesthetics.

The intent of forensic architecture field is to help the cause, providing help in the legal context. However, this raises the question of whether is it really doing so. As a matter of fact, the intention that the content at hand would count as evidence does not mean that it would actually be used as evidence. Indeed, Forensic Architecture presents its investigations to international courtrooms, parliamentary inquiries, and citizens’ tribunals. However, forensic architecture is not really used in court. An example can be found in the incident that took place in 2008, near Ni'lin, West Bank, where an Israeli soldier shot the Palestinian activist Asraf Abu Rahma. A Palestinian teenager Salam Kana'an recorded secretly the scene, and after the shooting the bystander dropped the camera. The video was considered as not unable to count as evidence because it did not allow visibility to see enough in the part when the tape turned black.

Nevertheless, digital forensics can be useful because the states' official versions of an event can be distorted for overturned through the cameras. Thus, forensic architecture is useful to produce counter visuality. Eyal Weizman – the founder of Forensic Architecture – thinks that through digital forensics, we can produce a counter narrative, using counter-forensic as a way to disrupt the state's narrative of some crimes for example.

Rebecca Stein deals with the questioning of the emerging field of digital forensics. Rebecca questions that the story of digital forensic is narrated from a liberation technology standpoint. The author is right that technology witness does not lead people to believe in what they see. What changes in the age of smartphone and camera normalization compared to the "early days" of digital forensics is the large amount of digital witnesses that led people to distrust visual testimonies. As a result, at a certain point, people are not convinced by the visual element, and keep believing what they want to believe. There was a consolidation of the repudiation in the age of the smartphone. People believe in what they already believe. In this regard, noteworthy of mention is the 2019 documentary "The Viewing Booth" in which Maia Levy – a Jewish American college student – who is a supporter of Israel is shown videos of Palestinian life under Israeli military rule in the West Bank, to make her think about her view about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. This demonstrates that it is not a matter of seeing pictures or videos, most people are going to still stick to their initial beliefs. Social medias push this closed-minded environments, creating virtual communities of people validating each other's opinion. This fuels polarized discussions thanks to the always most sophisticated algorithms on social medias, proposing in the for you page content that gives a user the "confirmation bias" reaffirming their idea on a matter.

youtube

0 notes

Text

BLOG 7

Comment on: DW Documentary "The propaganda war for Ukraine" and on Reading "Nuclear Cyberwar: From Energy Colonialism to Energy Terrorism" by Svitlana Matviyenko

"Everybody knows everybody lies."

President of Russia Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin excuses war in Ukraine with the “denazification of Ukraine” as a defense for its crimes. The Nazi concern argument comes from some of the volunteer brigades which fought the separatists in 2014 war, in particular the Azov battalion, that had far-right affiliations. Nevertheless, this battalion has been folded into the Ukrainian national guard as Ukraine needs these people now to fight back, and defend itself from Russian attacks. Thus, this justification could not count as a valid defense for Russian Federation. Putin’s claims have been largely rejected both internationally and by part of the Russian population, albeit not by everyone. A lot of Russian people keep supporting it, and being influenced by Putin's propaganda. As Svitlana Matviyenko points out, although Azov battalion had its history, currently it is a non-ideological army union. The "dehumanization" and "demonization" of this group by Russian propaganda then extended to all the Ukranian population. Before Russian propaganda talked just about that batallion, and from there, Ukrainian became to equal Nazis. For this reason, the surrender in Mariupol' of the Azov regimen of volunteer militias was an important point for Russian propagandists, who used them as symbolizing the reason why Russia engaged in the "fight against Nazis".

It is all part of reality distorting propaganda. Putin tries to recall history: depicting Ukranians as Nazis is an effective form of propaganda because it is hinting at a traumatic event in history for the whole world, appealing to the fear that Russia was risking to be subject of the same threat. However, the willingness to repeat something similar seems to belong to Putin himself. Two months after the invasion, in Russia was celebrated the Victory Day on May 9th, celebrating victory over Nazi Germany in WWII. This projection of the force present victory as force to gain glory. As a matter of fact, in Russian propaganda, they circulate stickers with written “we can repeat that”. In contrast to the slogan "we can repeat that" in Russia, there is the slogan “never again” in Ukraine. President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelens'kyj stated that decades after WWII, darkness and evil have returned to Ukraine in a different form, but with the same goal: bloody reconstruction of Ukraine, meaning the repetition of regime ideas, actions – which should never happen again. Zelens'kyj delivers the message that he does not want Ukranian soldiers to be glorious in defeating Russians, but that he just wants this to end, underying that Ukranian Army is forced now to do the things it is doing.

youtube

Putin’s propaganda is looking for new outlets. A member of the group moderator cyberfront Z platform – Dmitry Mahajev – states in the documentary that Ukranians are Nazis with the only aim in mind of killing Russians, so they had to respond. The documentary shows a video from April 2022, showing an alleged Nazi from Ukraine being captured for supposedly having targeted and planned to attack Russian TV journalist Vladimir Solovyov for spreading Russian propaganda. The video made public by Putin showed the apartment with a series of objects with the swastica recalling Nazism. The whole performance was set to persuade people and to bring credence to the claim that Ukraine is controlled by Nazis. It is all part of the "deception system" during this war.

"Protest in support of Ukraine in Trafalgar Square, London. Photograph: Vuk Valcic/Zuma Press Wire/Rex/Shutterstock"

One of the initial offensives of Russia's invasion of Ukraine was the occupation of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant on February 24th 2022. Few kilometers away from the largest nuclear power facility in Europe, Enerhodar, a satellite town was struck by a Russian rocket one week later. Ukrainian Territorial Defense units guarding the nuclear station threw Molotov cocktails at the Russian tanks in response to the continuous firing at civilian infrastructure, which caused the destruction of a residential building and a school. Then, local Ukrainian troops facilities withdrew, trying in vain to stop the troops, by shouting at the megaphone that since it is a nuclear industrial infrastructure, there was the risk of a nuclear accident. They urged them to "stop shooting and leave the premises!" calling it "an act of nuclear terrorism".

Such scenarios of "nuclear terrorism" are possible when there is a convergence of the two main forces of cyberwar: "cyber" and "nuclear" warfare. Cyberwar is defined as a manifestation of the ongoing technological changes – industrial, electronic, and cybernetic – through which capital keeps strong. The author stresses that cyberwar – in both its offensive and defensive elements – can be distinct from, occur before or simultaneously to other forms of hostility, such as the "kinetic" use of weapons, which is the real physical use. In multiple operations from the late 1990s to 2000s, there was an intersection between the cyber domain of war and that of nuclear conflict. Increasingly digital transmission systems — the failure of which could have disastrous consequences — are therefore necessary for the nuclear weapons' management and supervision. Additionally, as E. Gartzke and J. Lindsay holds, although cyber operations and nuclear weapons have essentially opposite destructive potentials, they are still "complementary".

The occupation of Chernobyl turned all the remaining nuclear energy production infrastructure at the plant into a nuclear weapon. This change is what makes it an example of an act of nuclear terrorism. War and terror are closely related, for example through strategic air bombing, sacking of cities, bombing campaigns of civilian centers to wake enemy morale. According to Charles Townshend, terrorism not only avoids combat, but it negates it by making self-defense impossible, striking targets indiscriminately, and without distinguishing between neutrals and belligerents, legitimate and non-legitimate targets. Thus, the essence of terrorism, rather than mere combat, is instead the negotiation of combat. Russian attacks on Ukraine seems to be a series of terroristic acts, attacking also defenseless people as a tactic to magnify anxiety. They have the first element of terrorism identified by Townshend of seizing attention by creating "shock, horror, fear or revulsion" through violence. Moreover, getting the message out (otherwise it is not going to shock) is the second element in the process of terror, which applies to this war. As with other terrorist acts, Russian forces' terrorist takeover of nuclear plants is media oriented, but only to the extent that they are able to control its exposure to orient the audience's gaze as it is convenient for them.

S. Matviyenko claims that the complete realization of the nuclear power station, as essential technology of modernity – far from having an accidental nature – occurred in 2022, as the result of an act of nuclear terrorism "with an imperialist genealogy" carried out throughout the conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BLOG 6

Comment on Readings

Chapters 2-3 from Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others (2004) and

Judith Butler's blog post "Precariousness and Grievability—When Is Life Grievable?" (2015)

In the late 19th century, the agonies of the battlefield became present as never before to those who read about them only in the press, and it was thought that one could know what happened daily worldwide. Despite this, it was not like one could really know what happened in the whole world in this way, just by reading newspapers. And the same holds for our times. The first important wars of which there are accounts by photographers are the Crimean War and the American Civil War. However, photographs of conflicts usually depicted the aftermath, such as landscapes left after warfare. It was the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) the first to be covered in the modern sense by professional photographers in the towns under bombardment, whose content could be found immediately in newspapers in Spain and abroad.

In the early 19th century, a famous concentration on the horrors of war and the crude actions of soldiers is Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) – a sequence of 83 prints created between 1810-1820, by Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya – first published in 1863. This collection shows the atrocities committed by Napoleon's soldiers who invaded Spain in 1808. Goya's images attack the viewer’s sensibility, moving them almost to horror. The cruelties shown in Los Desastres de la Guerra are intended to shock, wound, and awaken the viewer. All the embellishments portraying war as a spectacle have been removed: the landscape is barely sketched, creating an atmosphere of a darkness.

Since it it so profound, original, and demanding, Goya's art marks a turning moment in the history of moral feelings and of sorrow. While the caption of a photograph is traditionally merely informative and neutral (a name, place, or date), and the image is an invitation to look, Goyas’s captions point out the difficulty of only looking. Every image in Goya's print series has a brief caption lamenting the evilness of the invaders, and the inhumanity of the pain they caused. Provocative phrases ask the viewer questions as “can you bear to look at this?”. With Goya, a new “standard for responsiveness” to pain is introduced.

According to S. Sontag, there is a link between photography and death, as there is always a little bit of the element of death present in any picture depicting people. Since the invention of the cameras (1839), photography has gone hand in hand with death. Being the audience of the suffering occurring elsewhere is a “quintessential modern experience”. It is precisely modernity and mass media that have brought mediated spectatorship. Before the advent of mass media, spectatorship of pain was not possible in this way. Camera's reach was limited, until the camera evolved to be equipped and portable, allowing close shots from a distant point, gaining superiority over verbal tools in delivering the horror of mass killings. In modern times, when we are surrounded by information and imagery, a photograph is a quicker and more impactful mean of apprehending something and remembering it. In other words, images stick to our minds and memories better than words. Obviously, language has a weight, but pictures are more eye-catching, thus, they shock in a different way, through an element of trigger and surprise.

Sontag refers to today’s wars as “living room” wars because they are made of sounds and sights, and people can follow them from the comfort of their couch on their living room. The argument is that violence leads to audience, and to a response in some cases. The most compelling news has always been war. Spreading awareness about what happens in other countries draws attention on, and shapes, violence and wars. This is because the understanding of war in people that have not experienced it is a product of the impact that the news and images circulating have on them. The knowledge of the pain going on in other places is constructed. In this sense, an event becomes real to those who are not physically there as a result of watching news and photographs. As long as one does not get informed about a war, by seeing pictures, it is like it does not feel real; thus, they are less affected and touched by it. Nevertheless, experiencing agonies and tragic events rarely look like how they are depicted. Just as stated above that one could not really know what happened just by reading newspapers, the same holds for photographs, if not worse. An image is considered fake when it deceives the viewer about the scene it portrays. Many of the iconic news images from the past – including some of the most remembered photos of WWII – were found to have been staged. In the era of digital photography, with Photoshop and applications to edit pictures, it is easier than ever to make manipulate photographs in order to misrepresent conflicts.

The image as shock can soon become cliché image. The understanding of war mediated by cameras is characterized by shocking images of ruin or atrocities that become “ultra-celebrated”, becoming familiar to most people. This can end up anesthetizing the viewer, who becomes always less and less shocked by images of this kind.

Pictures of tragic events are perceived as more authentic if they do not look lighted and composed, while photographs that look not edited seem less manipulative. All images of pain widely circulating are under that suspicion, thus are less likely to spark empathy and compassion easily. A photograph’s meaning and the viewer's response depends on how the picture is read or misread, identified or misidentified; ultimately, on words. For this reason, in the past, on newspapers it was the picture to accompany the story, but later, the war photograph published in a newspaper was surrounded by words. It is the interpretation, or sometimes misinterpretation, of a picture that makes a difference. The intention that the photographer has in mind when taking the picture does not determine the meaning of the photograph, which rather will be dictated by the emotions, sympathies, and biases of the various groups that see it. For example, some people do not question the motivations given by the government for waging or continuing a war. It takes some particular circumstances for a war to become unpopular. If a war becomes criticized, the content of the conflict gathered by photographers can play an important role. For example, antiwar photographs – thought by someone to unmask the harsh reality of the war – might be read by someone else as showing heroism of young men doing their unpleasant duty in a necessary struggle, fighting for victory.

Memory is mostly local, and also memory of war, in the sense that people of a nationality will remember very well a genocide committed against their people. However, most wars do not acquire the fuller meaning necessary for it to become subject of international attention, that is being regarded as an exception, representing more than the clashing interests of those soldiers.

This is enough to understand that there are some sufferings that are perceived as more shocking, and others less. For instance, the suffering often deemed worthy of representation is those understood to be the product of human evil, as opposed to suffering from natural causes, as childbirth illnesses, which is rarely represented in art’s history, and perceived as destiny beyond contesting.

According to Butler, recognizing that a life can be injured, and destroyed, implies to acknowledge that a life is finite – the certainty of death soon or later – but also its precariousness, meaning that a life requires certain social and economic conditions to be sustained. Everyone potentially has the power to be destroyed and to destroy. In a way, humans are bound one to another in this precariousness: "we are all precarious lives". Given that a human being might die, it must be cared for in order for it to survive. The worth of life only becomes apparent when the loss of life would actually matter. Therefore, grievability is a prerequisite for a meaningful life. This raises the question of whose lives are regarded as valuable, mourned, and whose are deemed ungrievable. During armed conflict, populations are split into those grievable and those ungrievable. Ungrievable existences are those that cannot be mourned because they have never counted as a lives in the first place. From the viewpoint of those who wage war to defend the lives of some communities – even if by taking lives of others — we can see the world's division into grievable and ungrievable lives.

From a political point of view, the uneven distribution of public grief is incredibly important. Open mourning is linked to outrage, which in front of unjust treatment and loss is a huge political tool. Open grief and outrage bring affective reactions controlled by power structures, and in some cases subject to censorship. For instance, following 9/11 attacks, graphic images of the victims appeared in the media with names, biographies, and the reactions of the relatives. Since public grieving was dedicated to make these images iconic for the country, there was way less public grieving for non-US citizens, and zero for people working illegally.

Similarly, despite the differences of the contexts, when Abu Ghraib photos depicting torture carried out by US personnel were first made public in the US, conservative television figures claimed that it would be anti-American to broadcast them. For them, the public was not meant to have access to such graphic evidence and have knowledge of US's human rights violations, nor knowledge about what was going on during the war. Knowing that it would cause the public to turn against the war in Iraq, those trying to reduce the power of the photographs were attempting to reduce the power of outrage.

Certain interpretive frameworks have the power to subtly control our moral reactions that initially manifest as affect. According to Talal Asad, under some circumstances, we experience more horror and moral revulsion when faced with the loss of some lives, compared to others' lives. How we perceive the world has an impact on how we feel, and the way in which we interpret our feelings alter the feeling itself. This raises the question of whether recognizing that interpretive schemes shape affect can help us understand why we experience horror in response to some losses, but indifference in response to others. In the current climate of conflict and nationalism, individuals tend to feel that their life is bound with those with whom they share national identity, who are identifiable with us, and who adhere to certain culturally specific ideas. This framework works by implicitly making a difference between the populations seen as threatening one's life, from populations on which one's life relies. For example, in the case of Rodney King’s beating by the police, taken by the racist interpretative framework, King was seen by the white paranoid audience as a threat just for being a black man. Thus, the court did not empathize with his pain. Even worse, King's suffering inflicted by the police’s violence was understood as just and necessary.

Think about how this applies to the Western perception that Islam is "barbaric" and has not yet attained the civilization standards. The deaths of those killed do not fill Westerners with the same outrage as the deaths of people who share the same nationality or religion because they considered as not fully human. A further recent instance is provided by Europeans being more touched and showing more support to victims of the war in Ukraine – since Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 –, with large coverage in Western media than it has ever been shown for other ongoing conflicts outside of Europe. People in European countries, even unconsciously, tend to feel more moral outrage for losses of Ukrainian lives than for example victims of war in Yemen, due to the fact that they feel closer to Ukrainians, as being more geographically close, and supposedly sharing the same European values and background. For example, CBS News senior foreign correspondent Charlie D’Agata claimed that Ukraine “isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European – I have to choose those words carefully, too – city, one where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen”. The Guardian article "They are ‘civilised’ and ‘look like us’: the racist coverage of Ukraine" by Moustafa Bayoumi deals with the problem that many seem to think that Ukrainians are more deserving of sympathy than Afghans and Iraqis.

Although some populations are portrayed as threats to life by the rationale of self-defense, they are living populations with whom cohabitation implies a certain degree of interdependence. As Butler puts it, war tries to deny the unavoidable ways in which we are all dependent on one another, exposed to the destruction of the other, and in need of protection through international agreements founded on the recognition of "shared precariousness".

1 note

·

View note

Text

BLOG 5

Comment on Readings Mbembe, A., & Meintjes, L. (2003). Necropolitics. Public Culture, 15(1).

and 'Critique of the Black Reason (2017)' 'Introduction. The becoming black of the world'

Modernity is at the root of different concepts of sovereignty, taking the distance from the traditional concept of “sovereignty”. Western modernity understands sovereignty as the production of general rules by a body composed of equal and free people capable of self-representing themselves. During the enlightenment, there was a shift in part of Western thinking: before 1700, everything was explained spiritually in terms of good/evil. People committing crimes were believed to be motivated by God, or demons; so, sometimes they were even tortured to get the demons out. Therefore, there was not a sense of the individual to make a choice. From this, there was a shift to the classical theory of crime, a more scientific view with humans at the center, recognizing human ability for rational thought, and that humans can make progress with science, without God. A positive aspect of the classical theory is certainly this shift involving the development of the concept of free will, for which individuals can make their choices, deciding to do something harmful for other people or not, being in charge of their own destiny.

According to Western modernity, the concept of reason is a central element in understanding sovereignty because the use of reason is closely linked to that of freedom and free-will, which are fundamental components of autonomy and independence. In his essay “Necropolitics”, the Cameronian philosopher Achille Mbembé holds that killing or allowing to live are the limits of sovereignty. The capacity to choose who gets to live and who gets to die is where sovereignty finds its ultimate expression. In this view, exercising sovereignty implies exercising control over mortality. Hence, life is seen as a manifestation of power.

The essay builds on Michel Foucault’s concept of 'Biopower', which is sovereignty exercised over life. Biopower is defined as the domain of life over which power took full control, which ends up to be exercising authority over all aspects of the organic life (bio). Therefore, state power's control extends also to power over the physical bodies of a population, such as through deciding on women's abortions. Just last year, in June 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade case, holding that there is no longer a federal constitutional right to abortion in the US. This means that abortion rights will be determined by states, but nearly half of them have already or will probably pass laws that ban abortion, while others already took strict measures to regulate the procedure, which is a major retrograde step in civil rights. Ultimately, governments decide what to do with people's life, from their bodies, to their death.

The concept of 'Necropolitics' describes a way to exercise sovereignty, and it builds on a certain idea of sovereignty: sovereignty becomes the right to kill. While biopolitics is the right to decide on people's rights (from bios), necropolis – from the Greek word nekrós = dead – stands for the right to rule over other people's death. Necropolitics is concerned with the contemporary ways in which life is subjected to the power of death. Necropolitics is defined as the power and capacity to dictate who may live. It is about declaring war to the very existence of subjects, groups, or entire populations which are considered not worth living. This raises the question of who gets to decide whose life is worth living and whose life not? Although this sounds absurd and unfair, several examples in history have showed, and still show, that governments in many instances self-proclaimed the right to this decision based on the assumption that some people do not deserve to live.

A current example of a government performing the right to choose over people’s life is China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. The Chinese government's is employing arbitrary detention, torture, forced political indoctrination, and mass surveillance of Xinjiang’s Muslims. On this topic, I suggest the Amnesty International video entitled "China's False Propaganda and Torture in Xinjiang". The Uyghurs are a predominantly Muslim Turkic ethnic group with their own language and culture, the majority of which live in Northwestern China, in Xinjiang. Since 2015 approximately, a huge number of Uyghur people have been detained in what the Chinese state defines as "re-education" camps. Former Uyghur detainees describe crowded cells, brainwashing that drove some to suicide, torture during interrogations, food deprivation as punishment, beatings, being shackled to chairs for long periods of time, sleep deprivation, being forcibly drugged, being shocked in electric chair, and other forms of extreme physical and mental abuse. Various human rights’ activists around the world accuse the Chinese government's treatment of Uyghurs of attempting to whipe out a culture and to assimilate it.

"A photo posted to the WeChat account of the Xinjiang Judicial Administration shows Uyghur detainees listening to a 'de-radicalization' speech at a re-education camp in Hotan prefecture's Lop county, April 2017."

In order to understand Mbembé’s main points, it is important to understand Giorgio Agamben’s concepts of the ‘State of exception’ and of ‘Bare life’. The ‘State of exception’ is the extralegal exercise of surveillance, detention and torture performed by democratic countries. In these states of exception, rules of law are suspended by neo-liberal democracies (e. g. Italy, the US). In other words, the infrastructure of law that protects citizens against State’s violence is temporarily put in hold, and the law do not apply for certain categories. The "zones of indistinction" are the spatial manifestations of state of exception, and stand for the grey areas in which state of exception is implemented. This is the instance of the detention center for migrants in Europe, where the migrants’ freedom of movement is suspended even though it is in the Constitution. Such centers in Europe, and in particular in Italy, have sparked increasing concerns and criticism from human rights groups claiming they are inhumane.

A further example of the manifestation of 'state of exception' is the military prison at Guantanamo Bay established in 2002 to hold detainees engaged in then-President George Bush’s “war on terror”, and the US government's serious breaches of human rights there. The prison was purposely founded on a US naval base in Cuba, which Bush's lawyers claimed was beyond the jurisdiction of usual US law, so that prisoners brought there would not have to undergo a trial in a US court, and would not be secured by the US Constitution's limitations on torture and violations of human rights. Guantanamo Bay continues to hold around 30 men, the majority of whom are being held without charges, and none of whom have received a fair trial.

"In this photo reviewed by US military officials, flags fly in front of the tents of Camp Justice, April 18, 2019, in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba. © 2019 AP Photo/Alex Brandon"

Another key concept by G. Agamben is the one of 'bare life', which means life in general, without political or legal rights. Bare life is "Zoe", a Greek word indicating the state of everyone having vitality, an undistinguished form of life, as opposed to the above-mentioned Greek word "Bios", which stands for life with human dignity. People living in a state of exception have no political status, and are reduced to bare life. For this reason, the idea of the state of exception has been brought up frequently in conversations about the Holocaust and Nazism. Nevertheless, Agamben contends that the state of exception moves from being a temporary suspension of the rule of law into a lasting spatial structure that continues to exist outside the usual rule of law.

Agamben's thought can be linked with Mbembé's main concept from "The becoming black of the world". As the title already suggests, the author argues that the whole world has become black, with the word black in this context conveying the significance of violence and instability. Europe is no longer the center of the world, the black condition has extended to all humanity. As we saw in the paragraphs above with the concept of 'Biopower', power takes full control over life, exercising authority over all aspects of lives. There are many contemporary ways in which life is subjected to the power of death, and governments decide what to do with people's lives. Therefore, according to Mbembé, the condition of being subjugated to other people's willing is extended to everyone.

In the new form of capitalism, we can see how this happens in several ways. Today, platforms and social medias commodify every aspect of human lives, in a way to extract value from people's lives on digital media. For example, the "attention economy" is the economy defined by big corporations to make the users stay in front of the screens on the platforms as much as possible. Thus, the product sold is our attention. And with algorithms and the gathering of data, they are getting smarter and smarter in doing it. The issue of the dangerous human impact of social networks is well-explored by the Neflix documentary entitled "The Social Dilemma".

youtube

Ultimately, even proposing adverts based on individuals' research, is still a mean of influencing purchases, choices, affecting the world's behaviors and emotions. Hence, it can be seen as one of the several ways in which power exercise control over lives, and our condition is subjugated to someone else's will.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOG POST 4 - CMS/PL 348

Comment on Reading "The Appearance of Black Lives Matter" - (Nicholas Mirzoeff)

The root issues that gave rise to Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement are institutional racism and police brutality in the US. Police is heavily biased against visible minorities in the US, particularly against African-Americans, but also Natives and Hispanics, which are much more likely to be shot by police. There are huge racial disparities in how US police use force.

In the 2016 song “Blue Lights" performed by Jorja Smith – young singer and songwriter – she touches the issues of discrimination, racial bias, and police brutality. The music video shows Black men and boys that because of racism, are targeted by police for doing normal activities. The song says “If you’ve done nothing wrong, blue lights should just pass you by", which is how it should be. However, then Smith proceeds to sing "level of a felon when I've done nothing wrong, blood on my hands but I don't know where it's from", followed by the bridge that suggests to run when you – referring to a Black person – hear the sirens coming because they will be coming for you.

These racial inequities and killings have sparked criticisms of law enforcement, as well as concerns that black lives are less important to police than lives of white people, which culminated in the Black Lives Matter movement.

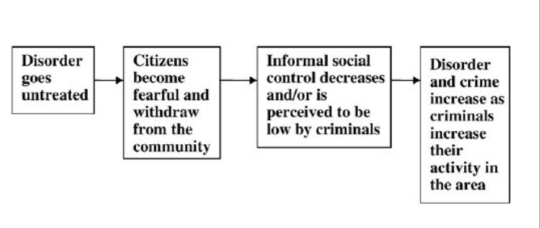

Noteworthy of mention in this regard, it is that one of the causes of the racial bias in US police can be identified in the theory of “broken windows” based on a research of the 1980s by social scientists James Q. Wilson & William Kelling. This theory claims that in order to maintain order and prevent chaos, the marginalized shall be controlled. The roots of the broken windows theory are well explained by artist Molly Crabapple in the presentation “How ‘broken windows’ policing harms people of color”. The name of the theory came from the argument social psychologists and police officers tended to agree on: that if a window in a building is broken and left unfixed, the unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, thus it will lead more criminals to break more windows.

This is important because it led to strict policies in the US, especially in New York, trying to eliminate signs of degradation, by using “over policing” in hotspot places, meaning in neighborhoods considered more criminal than others. These hotspots places were where often poor minorities lived, which instead of feeling safer, they just felt overly watched. The argument made is that these preventions exacerbated racism and surveillance, as well as reinforcing social hierarchies, assuming that white people with money abide to rules, while poor Black people did not, and those are the people America did not want to see. This situational prevention strategy does not get at the root of the causes resolving the phenomenon of crime, but it just tries to hide some people. For this reason, it was and it still is so important to claim back the right to be seen.

Mirzoeff looks at BLM movement as a process of de-colonizing, for Black people to reconquer a position of visibility, reclaiming their position in history. An important concept in the reading is the “space of appearance”, which is a mean to catch sight – albeit temporarily – of a future society that has not happened yet, but potentially can come. For Mirxoeff, the space of appearance is not universal, and we have to think of it as something that can be fixed, in the sense that we can change the situation. His invitation is to keep actively looking, as it is the only way in which visuality can be changed. The author talks from a non-Black perspective, as he is a Jewish man, thus he states “I see you and you see me”, referring to Black people. He deals with a collectivity that sees others, and finally is seen, or at least is pushing and demanding to be seen. The freedom of appearance is a practice through which people make themselves visible to each other. An example of how this works is the relationship between Black Lives Matter and Palestine, seen when an active resistance began in Ferguson, following protests after the shooting of black teenager Michael Brown Jr. by an officer. Palestinians sent messages of support, as well as practical advice on how to deal with tools of counterinsurgency. The Black-Palestinian solidarity in their struggle is shown in the 2015 Youtube video entitled “When I See Them, I See Us”, with around 60 African Palestinian and American activists and artists participating. There was, and there still need to be, a powerful awakening of the gaze of people. BLM protests shed light on the ability to look in the eye of power – in this context the police – and claim not only the right to look, but also the right to be seen.

In the above-mentioned video, the sentences used "We are not statistics. We have name and faces." make reflect on how often it is talked about victims in terms of numbers, as if we were not talking about human lives, each with their own identity. I wish we could remember all the names and faces of the victims, because it would mean that they were a few, albeit it would still be grave. However, sadly, it is hard to know by heart all of the victims, even just Black victims of killings by the police, for how many cases there were, and currently are. Unfortunately, these killings are not isolated incidents, but they are part of the systemic violence and racism in the US. For instance, in Italy, where the problem of police brutality is not systemic, but sporadic, the case of a white man's death by the hands of police officers is widely known by everyone. In Italy, everyone knows the name and the face of Stefano Cucchi, in the pictures below. He was a 31-year-old man from Rome, who in 2009 was arrested because he was found in possession of drugs. He was given pretrial detention (custodia cautelare) in prison. Seven days later he died in a hospital, where his body was full of signs of beating. This was the beginning of a complex and long search for the truth carried out mainly by his sister, Ilaria Cucchi. In 2019, the Court of Assisi of Rome sentenced two carabinieri to 12 years for manslaughter. I wish we could remember the victims of police brutality in the US as if it was the exception, rather than the practice. But, how many lives will it take for police brutality in the US to stop?

Space of appearance enters in action when the society of control – the system and the surveillance – start to show fractures. BLM, even if it started online with the #BlackLivesMatter, it allowed to gather people initially as a virtual circle, and then create a group in real life in squares. In other words, space of appearance is an account of different modes of appearance, both in the media and in public spaces. Space of appearance manifests through two shapes intertwined: the “kinetic”, that is the live space in which real people are physically present, and interact with each other; and the “mediated” form, the mediated documentation given by the importance of social medias and the hashtags.

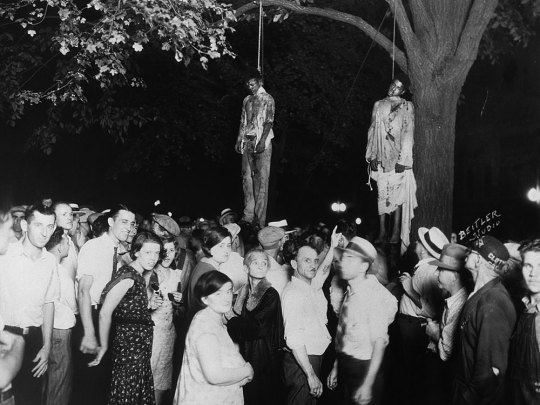

Mirzoeff goes back to the history of slavery in America and the “oversight” of the master surveilling enslaved individuals. He reflects upon how slaves looking at their masters could be dangerous, and be punished with their lives. Similarly, in the Jim Crow period (1877-1954), the so-called “reckless eyeballing” was the looking at white people, leading to legitimized violence and killing as a response. Black people were lynched for this alleged look. This was the case of the 14-year-old Black teenager Emmett Till who paid with his life merely for a rumor of having looked, or made advances on a white woman.

In contemporary times in the US, the figure of the master has been substituted by the police as an institution, for which even a defiant look by a Black person meeting the police gaze can be paid with life. Speaking about Black people reclaiming the space of appearance, an example is represented by the iconic picture of a Black woman alone standing proudly and firmly in the roadway to protest in front of police officers. She is intentionally looking directly at them, to show that she is not afraid.

A further visual example showing this defiant gaze towards the police is the 2015 remarkable picture presented below, in which a Black teenager protesting was confronting a Black cop in Chicago, while staring him directly in the eyes. The fact that the police officer is African American too, and the fact that even Black police officers in some cases were responsible for the death or beating of Black people – as the death of Freddie Gray, and the recent beating of Tyre Nichols – show that systemic racism in the US operates even beyond the race of each individual. Systemic racism is so inherent to this order, that is has to do with the position from which it is possible to look; in other words, power. This recalls the example of the US woman soldier at Abu Ghraib – who was lesbian –but still torturing Arab detainees in the name of their “deviance”, depicting them as homosexuals performing sodomy. The girl, being in a position of power, despite her sexual orientation, was representing heteronormativity in that context.

Another way of performing vulnerability in public spaces is appropriating a space that has another functionality, and powerfully reversing the function of a space that is not supposed to be political, but it is made such, outside from the normality. This is the example of the Oakland Bridge in San Francisco, which is a space used for circulation and commerce, and in 2016 was taken over by BLM protesters blocking traffic. Unlike the mediatic form of “space of appearance” and #BLM movement, where people can ignore the issue more easily, this form of live protest breaks people’s routine, forcing them to actually stop, and think about the cause of the protest. This bridge is mainly understood as a “white place” because it does not hint in any way at Black Americans’ history and colonialism. Mirzoeff considers it representing mainstream America and the US system, which is inherently white and racist.

In addition, a tactic that was employed by BLM protesters is the “die-in”, meaning protesters laying on the ground still, as if they were dead, causing disruption in public places. One of the first mass die-ins was in 2014 in New York, in the Grand Central Station during the rush hour, which continued every week for a year. This performing is very powerful even visibly, as the protesters are in an horizontal defenseless position on the ground, symbolizing the death “sentence” given by police officers to Black Americans. The formal repetition and similarity of the actions in protests for Black lives stands as a means to deliver the urgency of the situation, and it can be also seen as a comparison: just as the repetition of the same violations with same patterns and elements – a Black person (victim) killed by police officers (the perpetrators) –, protesters reflect this repetition and similarity in their protests.

Here in the picture above, we can see that not only the protesters' position expresses their vulnerability, but some protesters even have their hands up. The hands up is the signature gesture of the post-Ferguson movement, which is a powerful action of mimicking what Black victims are usually doing when they are shot or beaten by police. This gave rise to the slogan “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot”, which was even printed on protesters’ shirts. This slogan brings attention to the exact moment in which the Black person is showing that they do not have a gun, declaring their status of being harmless, when every person with reason would stop, but the US police do not cease, and still kills them. From a verbal and visual level, the gesture and the slogan show the cruelty and arrogance of the police that even in front of a weak defenseless person, do not have mercy and humanity. The sentence “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” alone manages to explain and make visible in people’s minds the scene that occurred, even when it was not documented in videos or pictures. This allows people to engage and empathize with the victim. The Hands up, far from being a passive form of protest, its strength relies in the second part “don’t shoot”, that is a command to the police, calling for the prohibition of any future killings.

A further act of civil disobedience not involving aggression, but "passive resistance", which is very smart from a visual point of view is the chain protest, as performed at Donald Trump’s inauguration on January 21, 2017. As shown in the picture below, BLM activists chained themselves together at one of the entrances to the inauguration of Trump. Protesters chaining themselves clearly evokes slavery; thus, the police to remove Black people from the streets have to cut the chain, making the symbolic action of freeing them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BLOG POST 3 - CMS/PL 348

COMMENT ON READINGS:

Authors Elsa Dorlin (Author) Kieran Aarons (Translator) Print Book2022English-language edition.

AND Butler, J. (1993) ‘Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia’, in Gooding-Williams, R., Reading Rodney King Reading Urban Uprising, New York and London: Routledge.

Elsa Dorlin identifies the historical roots of racial violence in the US in the right to self-preservation, and most importantly in the correlated right to armed self-defense. This latter originated in the Anglo-Saxon legal culture, and was then incorporated in the US Constitution. The right to armed self-defense’s origins are to be found in the need to increase the force for policing or military purposes, together with the right to own a weapon. The right to armed self-defense seemed to be understood as a “natural” right, but this raised the question of whether it was a non-derogable right for every individual to defend themselves, or if it was a right only reserved to citizens’ militias. Indeed, not everyone had this right, and certainly not Black people ... Just owners of property could completely exercise this right to self-defense, as it also involved property. Notwithstanding the laws implemented in England that regulated civilians’ arms, these rules did not consider properly the political question of self-defense, nor the disorder that an armed population would cause. Anyways, the Parliament in England restricted individuals’ manifestations of privileges to become vigilantes.

The history of the right to armed self-defense is intertwined with the rise of the liberal state – with its emphasis on property, and the right to privacy – and of judicial organizations. Up until the 19th century, just the wealthiest people could afford legal proceedings, due to the high cost of justice. As a consequence, protests and public meetings for the inability of the legal system to protect people and their property gave rise to prosecution societies. These societies consisted of the gathering of material, money, and human resources to contribute to the price of investigations, legal counsel, arrest and detention of criminals. They were formed to supplement the law and the justice system, that was deemed dysfunctional in protecting citizens and their property. In this way, people were capable and entitled to protect their property, by harming or even fatally shooting at other people, without waiting for the judicial system to do it. Generally, where the state does not arrive, someone else intervenes to fill the void, often leading to dangerous consequences. This recalls the way Mafia groups act in Italy: when immigrants land in Italy and need to gain money to live, the state is not there to help; so, there is when Mafia intervenes to give them a “job”, or better an opportunity. Basically, Mafia groups provide private protection of property rights and economic transactions that are not given by the state.

The right to armed self-defense raised a debate in American political culture. On the one hand, there was the argument wanting to restrict the use of weapons of individuals, leaving armed self-defense to militias, while others argued that it was a part of American citizenship that could not be eliminated. For the first time, the right to self-defense was understood as the citizens’ right to take weapons, and rely merely on their own judgement for their use, to defend themselves and their property, which became a crucial factor in American nation. The Second Amendment of the US Constitution protects the right of citizens to have and bring arms for their defense. This was confirmed even recently, despite the situation in the US, when in 2008, there was the Court’s historic decision ruling against the District of Columbia, prohibiting citizens from keeping arms in the houses. As a matter of fact, the issue of gun control is still very current in the US, where shootings are frequent, not only of Black people, but also of children in schools.

Indeed, self-defense is a key element of the colonial and racial history of the US, as well as its legitimization. The members of prosecution societies were portrayed as eternal pioneers who defended themselves against threats, fighting for the country, pushing back frontiers, creating cities on what was identified as the enemy’s territory, killing Indigenous people, seen as barbarians. This narrative gave a romantic vision, creating the myth of the white hero protecting the land, property, and money, thus romanticizing their violence. These groups are known as “vigilantism”, in support of armed self-defense, together with racist rhetoric. Vigilantism, what was a form of human hunting, constitutes one of the roots of white supremacy, the birth of the racial state and its legitimization – as put by Alexandre Barde. Vigilantism became one of the biggest representations of racist American criminality. The culture of early vigilantes as defenders of the nation, fostered the narrative of the supremacy of the white race, making it a reality.

It should go without saying that these vigilantes were far from being judges bringing justice. On the contrary, vigilantes wanted to get rid of judges, by presenting themselves as guards, police, and executioners. There were no procedural codes, no equity, nor the right to presumption of innocence, and not even right to a fair trial for the accused person. Punishments included reparations within a period of time, and when not respected floggings and banishment, as well as hanging for recidivism. These punishments were a mean to wipe out undesirable men seen as threats to white colonial society. In this way, they transformed the right to self-defense, into defense which was always legitimate; thus, any act of violence, in particular towards the black race.

As opposed to the representation of Lady Justice blindfolded, to symbolize her being impartial, making justice publicly (as in the picture below), vigilantes are depicted with masks to hide their faces and act at night – which can be interpreted as cowardly behavior. They are biased and without pity, moved by a desire to punish, in the name of “racial justice”, persecuting and executing the enemies of white society: those who are Black.