aspiring neuroscientist | personal blog and little tidbits i find interesting

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

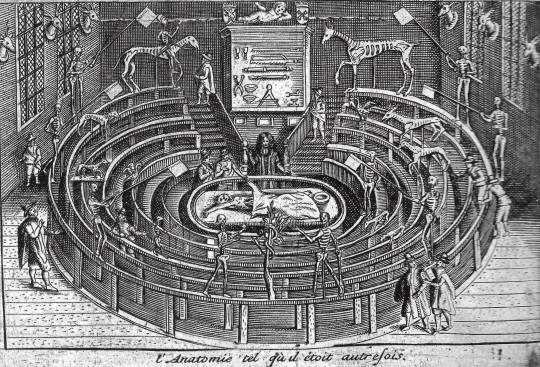

'anatomy as it was formerly practised' after willem swaneburgh, 1712 in the art of medicine: over 2000 years of images and imagination - julie anderson, emm barnes + emma shackleton (2011)

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Kalanithi, When Breath Becomes Air

#quotes#book quotes#neurosurgery#neuroscience#brain disease#medblr#medicine#literature#literature quotes#my posts

0 notes

Text

Paul Kalanithi, When Breath Becomes Air

#neurosurgery#neuroscience#quotes#book quotes#literature#medblr#medicine#doctors#neurosurgeons#paul kalanithi#when breath becomes air#my posts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hannah Close in conversation with Andreas Weber (2022)

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Read a Scientific Article

THE THREE-PASS APPROACH

The key idea is that you should read the paper in up to 3 passes, instead of starting at the beginning and plowing your way to the end.

Each pass accomplishes specific goals and builds upon the previous pass:

The first pass gives you a general idea about the paper.

The second pass lets you grasp the paper’s content, but not its details.

The third pass helps you understand the paper in depth.

At the end of the first pass, you should be able to answer the 5 Cs:

Category: What type of paper is this? A measurement paper? An analysis of an existing system? A description of a research prototype?

Context: Which other papers is it related to? Which theoretical bases were used to analyze the problem?

Correctness: Do the assumptions appear to be valid?

Contributions: What are the paper’s main contributions?

Clarity: Is the paper well written?

Purpose of the Sections of Empirical Articles

Section — Use it for

Abstract — This is a great section to read to find out if the article will be relevant to your own research.

Introduction — This section gives you an overview of work that has been done on topics relating to the hypothesis of the article, and will often lead you to other relevant work that has been done in your area of interest.

Method — This section will help you understand the design of the experiment. This is particularly useful if you'd like to replicate the study.

Results — The results will tell you what the author/s found in the course of their experiment.

Discussion — The discussion section is typically easier to read than the method and results section, and it will help the reader understand the implications of the results of the experiment.

References — This is a great place to look to find articles that are related to the one you are reading. If you're looking to build your own literature review, the references are a great place to start.

The Anatomy of a Scientific Paper

Some initial guidelines for how to read a paper:

Read critically: Reading a research paper must be a critical process. You should not assume that the authors are always correct. Instead, be suspicious. Critical reading involves asking appropriate questions.

Read creatively: Reading a paper critically is easy, in that it is always easier to tear something down than to build it up. Reading creatively involves harder, more positive thinking.

Make notes as you read the paper. Use whatever style you prefer. If you have questions or criticisms, write them down so you do not forget them. Underline key points the authors make. Mark the data that is most important or that appears questionable. Such efforts help the first time you read a paper and pay big dividends when you have to re-read a paper after several months.

After the first read-through, try to summarize the paper in one or two sentence.

If possible, compare the paper to other works.

Write a review that includes:

a one or two sentence summary of the paper.

a deeper, more extensive outline of the main points of the paper, including for example assumptions made, arguments presented, data analyzed, and conclusions drawn.

any limitations or extensions you see for the ideas in the paper.

your opinion of the paper; primarily, the quality of the ideas and its potential impact.

The guide below details how to read a scientific article step-by-step.

First, you should not approach a scientific article like a textbook— reading from beginning to end of the chapter or book without pause for reflection or criticism. Additionally, it is highly recommended that you highlight and take notes as you move through the article.

Skim the article. This should only take you a few minutes. You are not trying to comprehend the entire article at this point, but just get a basic overview. You don’t have to read in order; the discussion/conclusions will help you to determine if the article is relevant to your research. You might then continue on to the Introduction. Pay attention to the structure of the article, headings, and figures.

Grasp the vocabulary. Begin to go through the article and highlight words and phrases you do not understand. Some words or phrases you may be able to get an understanding from the context in which it is used, but for others you may need the assistance of a medical or scientific dictionary. Subject-specific dictionaries available through our Library databases and online are listed below.

Identify the structure of the article and work on your comprehension. Most journals use an IMRD structure: An abstract followed by Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. These sections typically contain conventional features, which you will start to recognize. If you learn to look for these features you will begin to read and comprehend the article more quickly.

Read the bibliography/references section. Reading the references or works cited may lead you to other useful resources. You might also get a better understanding of the basic terminology, main concepts, major researchers, and basic terminology in the area you are researching.

Reflect on what you have read and draw your own conclusions. As you are reading jot down any questions that come to mind. They may be answered later on in the article or you may have stumbled upon something that the authors did not consider. Here are some examples of questions you may ask yourself as you read:

Have I taken time to understand all the terminology?

Am I spending too much time on the less important parts of this article?

Do I have any reason to question the credibility of this research?

What specific problem does the research address and why is it important?

How do these results relate to my research interests or to other works which I have read?

6. Read the article a second time in chronological order. Reading the article a second time will reinforce your overall understanding. You may even start to make connections to other articles that you have read on this topic.

Identify Key Information

Whether you are looking for information that supports the hypothesis in your own paper or carefully analyzing the article and critiquing the research methods or findings, there are important questions that you should answer as you read the article.

What is the main hypothesis?

Why is this research important?

Did the researchers use appropriate measurements and procedures?

What were the variables in the study?

What was the key finding of the research?

Do the findings justify the author’s conclusions?

Sources: 1 2 3 4 5 6 ⚜ More: Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

583 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you stay on top of new research and history works? Do you have any advice for someone who is not a history student but wants to learn more, especially with legitimate research?

Howdy, Anon!

Honestly, I just periodically check certain places, such as major publications, or the social media feeds of some historians that I follow, as it’s likely they’ll be talking about whatever the new information is.

But regarding research advice, I would simply say… just start looking things up. An initial Google search is where I always start if I don’t already know where to find something. If that may be too overwhelming, Google Advanced Search can be quite helpful. If by “legitimate research” you mean work that has been peer-reviewed, places like JSTOR or Google Scholar can be good places to start, depending upon your topic and time period.

Primary sources can be more tricky, but generally I’d point you towards the Library of Congress (largest library in the world), the Internet Archive, and HaithiTrust. (each have thousands of digitized books spanning centuries that you can view and sometimes download). Checking your national archive is always a great place to go too, if you’re hunting for manuscripts.

In the realm of my history studies, the only real advantage I have is access to specific databases and collections that are behind paywalls through my institution. That doesn’t really amount to much in the grand scheme of things. You don’t need to go get a degree to research history. Plenty of authors of well-researched history books do not have a degree in the subject.

What a history degree really teaches you, in terms of research, is how to evaluate your sources. Who wrote the source? When did they write it? What is the author’s background? If the source is an article floating around the Internet, was it peer-reviewed? Does the author provide sources to their claims? If so, what sources do they provide, and can we trust them? All of this boils down to the process of critically thinking about the things you’re reading. Anyone can go through the process of looking at a source and asking themselves these questions to determine whether the source is trustworthy. Now, for the type of source (an 18th century letter vs. a peer-reviewed journal article about a topic mentioned in the letter) can cause these questions to change slightly, but those that I wrote above are a great place to start. I would also highly recommend that if a book about a historical topic (say, a biography) interests you, to flip to the Notes and Bibliography sections of the book to see what sources the author used, and thereby whether the claims they’ve made are legitimate. Just because someone got their massive biography about a famous dude published by a Big Five publisher doesn’t mean you should blindly trust them at face value.

Happy researching!!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cross sections of the brain show a healthy one at the bottom and an Alzheimer-diseased sample at the top. photo: Maggie Steber

730 notes

·

View notes

Text

my mom just had a 7cm brain tumor removed and since she's woken up she's been talking nonstop about this dream she had about going to an art gallery full of colourful paintings by a 'homosexual artist' named klimsdorf who was ethereal and wise, both young and old... at first she was convinced he was a real person but after failing to find him online she's accepted he was a figment of her subconscious mind and is now determined to bring him to life via painting his portrait herself. she's 67 and has never drawn in her life. and now this. blorbo from her tumor

173K notes

·

View notes

Text

Even though it's been months since I switched from neurosurgery to internal medicine, I still have a hard time not being angry about the training culture and particularly the sexism of neurosurgery. It wasn't the whole reason I switched, but truthfully it was a significant part of my decision.

I quickly got worn out by constantly being questioned over my family plans. Within minutes of meeting me, attendings and residents felt comfortable lecturing me on the difficulties of having children as a neurosurgeon. One attending even suggested I should ask my co-residents' permission before getting pregnant so as not to inconvenience them. I do not have children and have never indicated if I plan to have any. Truthfully, I do want children, but I would absolutely have foregone that to be a neurosurgeon. I wanted to be a neurosurgeon more than anything. But I was never asked: it was simply assumed that I would want to be a mother first. Purely because I'm a woman, my ambitions were constantly undermined, assumed to be lesser than those of my male peers. Women must want families, therefore women must be less committed. It was inconceivable that I might put my career first. It was impossible to disprove this assumption: what could I have done to demonstrate my commitment more than what I had already done by leading the interest group, taking a research year, doing a sub-I? My interest in neurosurgery would never be viewed the same way my male peers' was, no matter what I did. I would never be viewed as a neurosurgeon in the same way my male peers would be, because I, first and foremost, would be a mother. It turns out women don't even need to have children to be a mother: it is what you essentially are. You can't be allowed to pursue things that might interfere with your potential motherhood.

Furthermore, you are not trusted to know your own ambitions or what might interfere with your motherhood. I am an adult woman who has gone to medical school: I am well aware of what is required in reproduction, pregnancy, and residency, as much as one can be without experiencing it firsthand. And yet, it was always assumed that I had somehow shown up to a neurosurgery sub-I totally ignorant of the demands of the career and of pregnancy. I needed to be enlightened: always by men, often by childless men. Apparently, it was implausible that I could evaluate the situation on my own and come to a decision. I also couldn't be trusted to know what I wanted: if I said I wanted to be a neurosurgeon more than a mother, I was immediately reassured I could still have a family (an interesting flip from the dire warnings issued not five minutes earlier in the conversation). People could not understand my point, which was that I didn't care. I couldn't mean that, because women are fundamentally mothers. I needed to be guided back to my true role.

Because everyone was so confident in their sexist assumptions that I was less committed, I was not offered the same training, guidance, or opportunities as the men. I didn't have projects thrown my way, I didn't get check-ins or advice on my application process, I didn't get opportunities in the OR that my male peers got, I didn't get taught. I once went two whole days on my sub-I without anyone saying a word to me. I would come to work, avoid the senior resident I was warned hated trainees, figure out which OR to go to on my own, scrub in, watch a surgery in complete silence without even the opportunity to cut a knot, then move to the next surgery. How could I possibly become a surgeon in that environment? And this is all to say nothing of the rape jokes, the advice that the best way for a woman to match is to be as hot as possible, listening to my attending advise the male med students on how to get laid, etc.

At a certain point, it became clear it would be incredibly difficult for me to become a neurosurgeon. I wouldn't get research or leadership opportunities, I wouldn't get teaching or feedback, I wouldn't get mentorship, and I wouldn't get respect. I would have to fight tooth and nail for every single piece of my training, and the prospect was just exhausting. Especially when I also really enjoyed internal medicine, where absolutely none of this was happening and I even had attendings telling me I would be good at it (something that didn't happen in neurosurgery until I quit).

I've been told I should get over this, but I don't know how to. I don't know how to stop being mad about how thoroughly sidelined I was for being female. I don't know how to stop being bitter that my intelligence, commitment, and work ethic meant so much less because I'm a woman. I know I made the right decision to switch to internal medicine, and it probably would have been the right decision even if there weren't all these issues with the culture of neurosurgery, but I'm still so angry about how it happened.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

22.06.2025

Another photo from my camping trip and some more notes about neurogenesis.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fucking, thank god for grad students. Grad students are truly the GOAT of science. A lot of scientific research is limited by what kinds of research can produce results that might be profitable for businesses, including the journals that publish that research in the first place. But grad students? They're not trying to make money for anyone, they're trying to prove themselves as scientists before entering the professional world. The only thing a master's or doctorate thesis is supposed to do is prove to your university that you have mastered your craft and are capable of producing research that meets the standards of the scientific community. The only job that a graduate student has when producing that thesis is to do good research that has never been done before. They're just about the only scientists whose sole prerogative is to look where no one else has looked to answer questions that no one else has, possibly because no one else has even asked them yet, and to compile their results, whatever they are, for the pure sake of knowledge itself.

I'm not a scientist, I'm just someone who does scientific research in my free time because I'm deranged enough to think it's genuinely fun, and because a lot of the art I do is scientifically informed. But because I'm doing this research for art rather than a more "practical" application, a lot of the times the reasons why I want to know something are completely different from the reasons why these topics are actually studied. I don't want to know how to create synthetic equivalents of Feline Facial Pheromone F3, whose function we already know, in order to reduce stress and prevent undesirable behavior in pet cats in new homes and vet clinics, I want an analysis of the components that make up Feline Facial Pheromones F1 and F5, whose functions we don't know, in order to start building hypotheses about what those functions might be, so that I can figure out how catgirls would perceive these pheromones and theorize how they might talk about them in their native languages. But nobody's gonna pay me to do that, are they?

And let me tell you, sometimes the only people who seem interested in the kinds of bizarre and esoteric questions that an artist like me will have are grad students publishing theses. I still haven't found anyone trying to figure out what FFP F1 or F5 are used for, but I have found:

A full, comprehensive description of the complete phonology and grammar of the Lushootseed language and its dialects, spoken by several Coast Salish tribes of the Puget Sound region, published by Ted Kye in 2023 for his doctoral thesis at the University of Washington. Lushootseed is the source of many words from the region, including hugely important place names like Snoqualmie, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Snohomish, Sammamish, Duwamish, Mukilteo, Shilshole, and of course, Seattle, but the language itself is extinct, with its last native speaker, Vi Hilbert, dying in 2008. There are, however, efforts to revive the language, and that would be significantly more difficult without Ted Kye's work. I think we can all see why this kind of thing is valuable.

And, this second one is a bit more esoteric but hear me out:

The discovery that a popular ornamental aquarium fish might actually have been sequentially hermaphroditic this whole time, which was practically a footnote in a 2016 thesis by Lia Gomes and Silva Henriques from the University of Porto, in Portugal. The fish in question is the red-tailed shark, Epalzeorhynchos bicolor, which is not an actual shark, but a member of the carp family that just happens to look like a shark, and two very important things to note about it are that it is critically endangered in the wild, and in fact was thought to be totally extinct in the wild until one was found in 2014, and that they are also practically impossible to breed in captivity. The primary threat to the species is considered to be habitat destruction. The quite substantial supply of this species in the pet trade today all come from fish farms in Southeast Asia, which use hormones to induce reproduction in the species, through processes that are kept as trade secrets and are essentially unknown to the scientific community. So, we have literally no idea how this fish breeds, which means that hobbyists can't breed it themselves, and scientists don't know what conditions they even need in order to breed in the wild. This one paper, written by students in Portugal who attempted to induce gonadal maturation in the species using hormone injections, is perhaps one of the only clues we have on the path to saving this species, and it hints at a conclusion that could have HUGE implications for the husbandry, captive breeding, and survival in the wild of the red-tailed shark: all of the individuals that were dissected without having undergone hormone injections were immature females, and immature males only started appearing in groups that had been injected, suggesting that all individuals of the species might start out as females, and then at some point in their development, certain individuals, for unknown reasons, may develop into males instead, making them sequential hermaphrodites. This isn't unknown in fish (clownfish do something similar, except they all start out as males and become female when they achieve dominance in their social group), but it was completely unexpected in this species, and could go a long way in starting to explain the difficulties with breeding them and potentially be a step on the path to learning how to breed them in captivity, as well as saving them in the wild.

Unfortunately, in the latter case, I wasn't able to find any other published work by either of the listed authors, and no one else seems to have repeated the experiment. This is a real shame, because the results of the experiments, while very intriguing, weren't conclusive; they had a fairly low sample size, and would need to be confirmed by further research. But there's no indication of that research being done, and I might be the only one other than the university's board of reviewers who's even read the thing.

All this is to say, fish testicles are interesting and I'm begging someone to do more research on them, please.

879 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heyo it’s back to school time and here’s a research tip from your friendly neighborhood academic librarian.When searching for any topic on the internet just type in the word ‘libguide’ after your topic and tada like magic there will be several beautifully curated lists of books, journals, articles, or other resources dealing with your subject. Librarians create these guides to help with folks’ informational needs, so please go find one and make a librarian happy today!!

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

So earlier in art class today, someone drew a characters hands in their pockets and mentioned that hands are really like the ultimate end boss of art, and most of us wholeheartedly agreed. So then, our teacher went ahead and free handed like a handful of hands on the board, earning a woah from a couple of students. So the one from earlier mentioned how it barely took the teacher ten seconds to do what I can’t do in three hours. And you know what he responded?

“It didn’t take me ten seconds, it took me forty years.”

And you know, that stuck with me somehow. Because yeah. Drawing a hand didn’t take him fourth years. But learning and practicing to draw a hand in ten seconds did. And I think there’s something to learn there but it’s so warm and my brain is fried so I can’t formulate the actual morale of the lesson.

80K notes

·

View notes

Text

The genetic risk of developing Alzheimer's disease is more strongly influenced by the mother's side than the father's side, a recent study has discovered. Alzheimer's disease steals memories, independence and the capacity to connect with loved ones. In 2020, over 55 million people worldwide were living with dementia. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60-70% of all dementias. It's expected the number of people affected by dementia will nearly double every 20 years. Finding ways to better diagnose, treat and even prevent dementia is more important than ever.

Continue Reading.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

study with me study date 08-03-23 human resource management, part 1 | part 2 | part 3 | part 4

study techniques the feynman technique question bank method of study 45:15 pomodoro ~ study technique flashcards español resources active recall for studying how does active recall work? eat the frog (time management) dual coding spaced repetition

notetaking the mapping method the boxing method the charting method the cornell method the sentence method the outlining method sketchnotes taking effective notes in class

study schedules five hour weekend study schedule six hour weekend study schedule

study guides learning languages study guide

balance in academia the importance of balance in academia school, extracurriculars and balance working as a student

study skills optimizing your study environment improving your memory time management in the ib how to improve your listening skills in lectures how to take better notes during fast-paced lectures how to improve memory retention in lectures

study advice & tips how to effectively organise flashcards study tips take more breaks while working regular review seeking support when needed and the benefit of tutoring miscellaneous study tips connecting your daily work to your goals healthy eating as a student healthy habits for straight a's how to boost your creativity creative routines the benefits of group studying the importance of study checklist for the new semester

university/college the university masterlist how to get into a good university applying to schools (what to consider) what can you do with a biology degree?

my research/explorations don't forget to do your research (artificial intelligence) pretty privilege in academia important qualities for students

369 notes

·

View notes