A collection of thoughts and hand-drawn sketches that illustrate the value of looking closely at buildings and places. by Frank Harmon, FAIA

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Lenten Roses in Snow

It’s been a winter of political sound and fury. Scattered announcements, meant to knock us senseless, fly at us like the driven hail.

But in my garden one February afternoon, a bowl-shaped flower opened about six inches above the snow. My first Lenten rose. But, hey, who cares about a small, grey-green plant in a frozen garden when the country seems to be crumbling, right?

Well, me, for one.

I envy these flowers. In the cold of winter, just as the gardener despairs of spring, these slender petals open, keeping watch on the unshakable rhythm of life.

Not a raging orator, but sometimes a little pink flower in the snow can offer hope.

The poet Jim Harrison wrote, “The government offers you nothing but apprehension. Only you can offer yourself peace.”

The next morning, my Lenten rose had three new buds and I glimpsed an upward path: Its roots were spreading underneath the snow. Soon new colonies of flowers would burst into the light like little rays of hope.

0 notes

Text

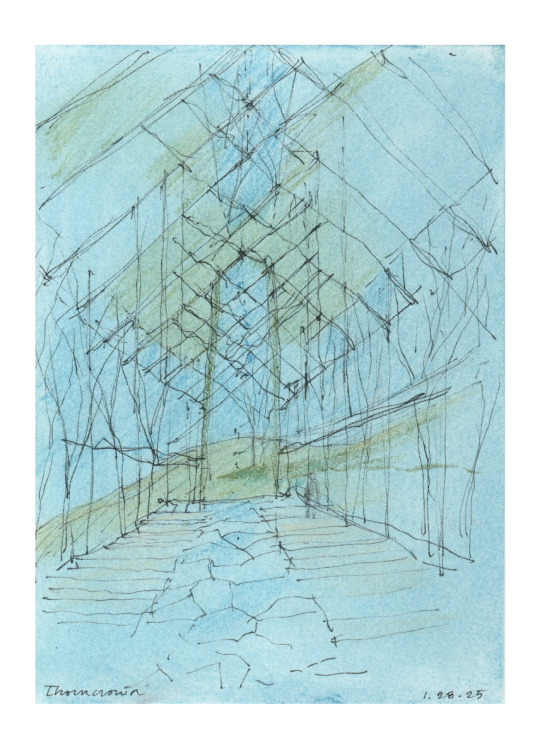

Thorncrown

We left Fayetteville, Arkansas, at 10:30 one recent morning and drove northeast across rolling hills dotted with dairy farms. We were on our way to see a tiny wood and glass structure nestled in the Ozarks near Eureka Springs.

At noon we arrived at our destination: Thorncrown Chapel, built in 1980 by a retired schoolteacher “to give visitors some inspiration,” he said.

That schoolteacher, Jim Reed, asked Fayetteville architect E. Fay Jones to design a “small glass chapel” on his property. Jones had apprenticed under Frank Lloyd Wright, and it showed. His stone and unpainted wood houses were celebrated for their uncommon, organic beauty within their natural settings.

Jones had waited 30 years for the opportunity to design a church. And yet, his concept for a roof woven from ordinary framing lumber, rising quietly among the trees, its whole footprint smaller than a pickle ball court, was too unusual for Mr. Reed. He rejected it.

Fay Jones, a gentle soul who never raised his voice, was crushed. So, Reed sought the opinion of friends and strangers, including “the lady at the cash register” at his local grocery store, who loved the design. So did many others. Kaboom! Mr. Reed built the chapel as Jones had designed it.

Seven million visitors have been inspired since.

Throughout history, nature always seems to be the setting for great revelations. A mountain top, a banyan tree, a burning bush. Sitting beside my daughter that January afternoon, we were bathed in sunlight inside a chapel made of 2x6s that anybody can buy from Lowe’s. But here they were put together with a tenderness akin to love. Suddenly I remembered that we are partly made from the residue of stars.

0 notes

Text

An Epiphany at the Loading Dock The buildings on the campus where I teach stand in a picturesque setting of stately trees and lawns. But in my student days I thought this landscape was so staid that at night I planted moon vines among the hedges.

Recently I’ve enjoyed walking through the jumble of service yards, emergency generators, and loading docks that serve the main campus.

One afternoon, I noticed a vigorous clump of holly trees growing beside a concrete loading dock. Such a lusty patch of green seemed out of place in a gritty service yard. I speculated that many years ago someone planted and then abandoned four small holly bushes. Eventually the bushes grew into small trees, until one day a contractor ringed them with a collar of asphalt. They simply grew taller and shaded the loading dock. Then an architect designed a building that blocked the sun. Still, the holly trees grew, reaching upwards to catch the morning sun.

Neglect was a sturdy shelter. No one came to prune or spread fertilizer or spray pesticides on the hollies, who looked after themselves.

If the ancient trees and lawns of main campus shape a setting of academic splendor, these forgotten trees in a leftover space are probably closer to real life. A mixture of divine and ugly, host to flocks of birds at night, vulnerable and resilient, bookended by pickup trucks, strange and beautiful and wild.

I didn’t see any need for moon vines.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folding Napkins I wash and fold about 12 napkins a week. Some of them are batik from Indonesia. My friends and I use them every Saturday when we get together for coffee and conversations. Folding these little scarlet and mocha-colored napkins lets me reminisce about my companions and look forward to next Saturday’s gathering.

The other napkins I fold are faded and a little frayed, like me. I don’t mind. Over decades these soft squares of cotton have witnessed contentment, anxiety, fear, irritation, and love as they’ve pressed against our lips.

So much in our world view demands excellence. One can be the best architect, the fastest swimmer, the most renowned surgeon. But folding linen is not on anyone’s 10 best list.

Anne Lamott writes, “Mother Teresa said no one can do great things, but we can all do small things with great love, and that is all we can do.”

One napkin at a time.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fried Chicken Backs

When my mom fried a chicken, she and her four children took most of the pieces as the platter went around the dinner table. My father served himself last. And he always chose the back, the piece with hardly any meat on it. He insisted that it was the “best part of the chicken.”

My father left his family’s farm to go to college in 1924. Five years later, The Great Depression would prove ruinous for his father – our grandfather — who committed suicide and left his family to carry on without him.

I believe our father vowed to himself that his children and their needs would always come first.

I can see my father clearly now. I can see him sitting at the maple wood table picking at his miserable piece of chicken and smiling. I can glimpse behind that smile and see the farm he never missed.

Most of all, I can see his love for us.

0 notes

Text

Mrs. Garringer's Field

I woke from a nightmare at 3 a.m. recently, and to calm myself, I went to Mrs. Garringer’s field.

When I’m tired or depressed or anxious, I sometimes go to Mrs. Garringer‘s field and sit in the shade of tall sweet gum trees with five-pointed leaves that turn bright purple in the fall.

I’ve played ball with my friends in Mrs. Garringer’s field, built forts, and scoured the tall grass with a butterfly net. The Plybons lived on one side of the field. Mr. Plybon gave me a quart of Texaco red enamel once to paint my race car. Mr. Wilson lived on the other side. He repaired lawnmowers and shared his arrowhead collection with me.

Mrs. Garringer’s field was plowed under 50 years ago and replaced by a red brick house, so now I go there in my imagination. But as Elizabeth Barks Cox wrote in Reading Van Gogh, “The place where we grew up works on us even if we never see it again.”

Eudora Welty called such a place “the heart's field.”

0 notes

Text

Leaving the Porch Light On

A neighbor across the street sometimes leaves the light on in his second story window. I saw its glow one morning at 4 a.m. as I left for the airport. Why did I find a light in his window so moving? Am I as a moth who sees hope in the dark?

Other people in my neighborhood leave their porch lights on at night. Each house is a different style and color, and no two families are the same. But almost everyone keeps a porch light glowing in the dark. At a time when the mosaic of the country may be shattering, is it possible to imagine that porch lights suggest E Pluribus Unum?

No matter how grand a building is, a small light may be more memorable. At Chartres Cathedral, sunlight passes through stained glass windows and splashes color on bare stone walls. What I remember most vividly, though, are the votive candles flickering in the alcoves.

Eudora Welty wrote, “The difficulty that accompanies you is less like the dark than a trusted lantern to see your way by.”

I’ll remember that tonight.

0 notes

Text

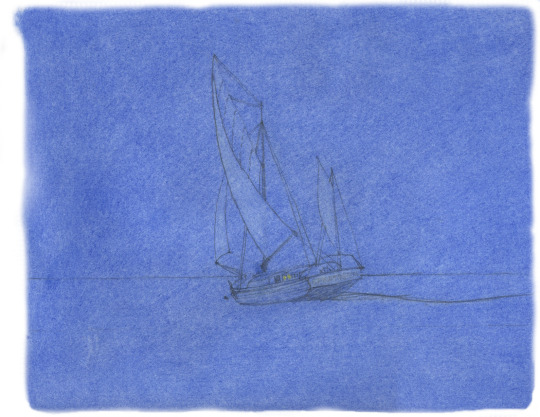

Sailing Alone Around the World

Captain Joshua Slocum (1844 - 1909) was the first person to sail single-handedly around the globe. In August 1895 he left Boston harbor in the gaff rigged wooden sailboat Spray and returned three years later.

Slocum navigated without a chronometer and used dead reckoning -- also known as guessing -- to sail the high seas. Spray was 36 feet 9 inches long and carried him 46,000 miles. He devised a self-steering apparatus that allowed him to rest. He never learned to swim.

In Sailing Alone Around the World, Slocum described his voyage:

“The sea was confused and treacherous. In such a time as this the old fisherman prayed, 'Remember Lord, my ship is small and thy sea is so wide.’"

During Slocum’s three-year voyage, the Spanish American War began, America was gripped by an economic depression, famines and disease stalked the world, Jim Crow laws were passed, and the first Olympic Games were held.

One hundred and thirty years later, we’ve got our hands full with war, climate change, famine, racism, and threats to democracy. As they sometimes do in these anxious times, my thoughts revert to Captain Slocum sailing alone at night in the middle of an ocean, his boat on auto-tiller, reading by the light of an oil lamp.

0 notes

Text

A Very Large Array The road to the Very Large Array goes past the Ponderosa restaurant in Magdalena (population 808) then out into the flat grasslands of New Mexico. Suddenly you see the first of 28 white-painted radio dishes pointing to the heavens, each taller than a 10-story building. You have arrived at the world’s largest radio telescope.

My friends and I visited the VLA on a sunny April afternoon in 2003. It was quiet as we stepped onto an orange shag carpet inside the nondescript control center building. Frank Sinatra sang in the distance.

We climbed the stairs, entered a windowless control room, and discovered that this massive scientific instrument, the largest in the world, was staffed only by one man: a technician wearing jeans, a plaid shirt, and sporting a grey ponytail.

His boombox played “Fly Me to the Moon” as the technician fiddled with the controls of the mighty array. Then I noticed that this master of the universe was eating an Arby’s “Baked Potato with Everything.” He had carefully placed little cups of sour cream and bacon bits like moons around the asteroid-shaped potato.

At 3 p.m., the man tapped a keyboard, took a bite of potato, and caused the giant radio dishes to scan the universe. Frank Sinatra took a breath.

A sixth grader with an iPhone has greater access to the world now than anyone in history. But the internet creates sameness. A mongoose and a galaxy are equal in size and importance on the digital screen.

Our brains are no longer conditioned for reverence and awe.

But that afternoon, I felt both awe and reverence. To go from a bacon bit to black holes in a single breath -- now that was cause for wonder.

0 notes

Text

A Fire on the Hearth

We had extremely cold weather here recently. Alligators froze in an icy swamp east of Raleigh. Children ice skated on a rarely frozen creek nearby. And at 7 a.m. this morning, my birdbath was a rock-solid disc of ice.

On my way to the birdbath, hot water kettle in hand, I noticed that someone had raked the leaves on the edges of our garden.

I soon spotted the obliging gardener. He weighs about two ounces and sports orange, black, and white feathers. He’s an Eastern Towhee. In the process of looking around for insects, he turned those leaves back as neatly as the sheets in a Marriott hotel.

Something truly is happening to the weather. Earlier this week, PhD economists meeting in a windowless room in a Grand Hyatt in San Antonio declared that climate change may overturn everything.

When the conversation is about the climate, I find it hard to satisfy every expert. Some say the wood burning in my fireplace is a good thing because it’s a renewable resource. Others say I’m polluting the atmosphere.

Either way, a fire flickering on my hearth on such a cold winter morning does wonders for my spirit.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Big Bin

Show me how you throw away your trash and I will describe your civilization.

In Switzerland it’s really hard to find trash anywhere except in a trash can. But leave a receptacle of any kind uncovered on a street in New York City and New Yorkers will put trash in it. This includes a window box, a bicycle basket, or the bed of a pickup truck.

The Swiss are a law-abiding people. New Yorkers are quick to take advantage of any situation, including throwing away their sandwich wrappers on windowsills. In Switzerland the trains run on time. In New York we throw trash on the train tracks.

The Vessel is another kind of receptacle in New York City. Built in 2019, the Vessel is an intertwined set of stairs rising 16 stories into the air. Intended to be a viewing platform and a centerpiece of Hudson Yards, the Vessel became a jumping-off place for four suicides. It's been closed since 2021.

Because of the Vessel’s resemblance to a trash can, my daughter renamed it "Big Bin." Another popular nickname is "the Great Shawarma." When I recently stopped by "the Great Shawarma," I noticed a litter of empty coffee cups and plastic bags around its base.

Meanwhile, the City of New York is replacing 23,000 wire street-corner trash cans with a sleek new design. If only New Yorkers will use them.

Ah, civilization.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Bear Lady

In her youth she had been a showgirl and dancer in Las Vegas. When I met her, she lived alone in a pine forest.

Kay Grayson was tall, lithe, fifty-ish, and had no teeth. “I talk to the bears,” she said. They tell me they don’t like all this destruction and development goin’ on.” Kay lived in a rusty trailer near the Alligator River in Tyrell County, one of the last wild places in North Carolina. The trailer had claw marks from top to bottom and was surrounded by piles of empty Entenmann's cruller boxes. Friends brought her kerosene for heating and cooking and stale supermarket pastry that she fed to the bears.

I met Kay on a sweaty July afternoon in the clearing she called home. While we were talking in the shade of her trailer, a mother bear and two cubs appeared not 20 feet away. Suddenly, the bear grunted, and her two cubs climbed a 50-foot pine tree in seconds.

“There’s a male bear I named Highway 64 near by," Kay said. “He’ll kill the cubs if he can." It's a long way from sequins in Las Vegas to cruller boxes in Tyrell County.

I wish Kay had lived to write her story. But in 2015, the sheriff found her body along a logging road. It was unclear if she had been killed by a bear. As her friend Willy Phillips said, “She lived on her own terms and died on her own terms.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moth The poet Baudelaire thought that genius was the ability to revisit childhood at will. Grammy award-winning artist and ethnobotanist Justin Robinson said recently that he always tried to do “What my 10-year-old self would be proud of.”

What is the genius we have as children? At age 10, we have the strength and agility to do almost anything we desire, the language to express ourselves, and, most of all, an unlimited curiosity. Our imagination is not fettered by shame or sarcasm.

I watched a little bit of genius unfold while I was sitting in a coffee shop recently. A broken fire hydrant, shattered by a truck weeks ago, teetered outside the cafe door. Dozens of people walked past the strange looking hydrant without noticing. About 8:30 a.m., two schoolboys came along. They pressed their faces to the hydrant’s iron rim to peer deep into the earth then jumped for joy.

When I got home, I noticed a thumbnail-sized moth resting on my garden wall. The whitish moth was trying to look like a patch of lichen so predators wouldn’t notice her. And it was hard to see that she was a moth.

I could easily imagine what the boys would say.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Small Fires and Milk My classmates had summer jobs in architects’ offices, but I worked for a construction company. We were framing a school one July afternoon when a thunderstorm headed our way. Some of us huddled in the construction shed.

Suddenly a flash of lightning and a terrifying thunderclap burst above the shed and we saw a ball of fire skitter over the steel frame of the school.

I loved those weather delays because I could listen to folks talk. I got an earful that day. “The only way to put out a lightning fire is with milk," the concrete finisher said. A carpenter looked out at the rain and said, “At my grand-maw’s house on Thanksgiving day once a bolt of lightning struck the top floor. A ball of fire bounced down the stairs and into the wood stove in the kitchen. It baked the turkey!"

Of course, their stories were folk myths and hyperbole, but I loved the way they matched our sense of wonder at the fireball.

Wonder and awe seem harder to come by these days. As John Updike once said, “We cannot imagine a Second Coming that would not be cut down to size by the televised evening news…” Or nowadays by social media.

Maybe it’s better to look for wonder in small places. Like a construction shed.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pawpaw The pawpaw is native to the East Coast and has the largest edible fruit of any native American tree. About the size of a small banana, the pawpaw fruit has a mottled green and yellow skin. Inside is a creamy yellow pulp that tastes of vanilla and mango.

Why is this delicious fruit, as common as native persimmons and walnuts, available only to a few dedicated enthusiasts?

The fruit bruises easily. Also, it has a short shelf life and ripens only in September. We’ve gotten so accustomed to buying apples, oranges, and strawberries year-round that we’ve forgotten the luxurious taste of a pawpaw in its short precious season.

When I stopped to sketch an abandoned farmhouse near the Santee River in South Carolina, I noticed pawpaws growing near the front porch. The fruit was turning greenish yellow but was not yet edible . When a pawpaw fell to the earth the farmer knew it was ripe.

We imagine that spectacular events make us happy, yet joy is born of small things, like the southwest breeze on a porch and fruit dropping to the ground.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Petite Maison

“The signals we give—yes or no, or maybe—should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.” William Stafford wrote in his poem “A Ritual to Read to Each Other.”

I remembered Stafford while I was making a sketch of La Petite Maison, a restaurant in the tiny village of Cucuron in Provence. I thought the signals La Petite Maison gave on that July afternoon were wonderfully clear and welcoming. The building itself seemed to have a smiling face.

So often I read of contemporary buildings that "challenge us" or make "statements." At La Petite Maison, there are no statements. It’s not the sort of place where people have power lunches or take calls.

While I was making the sketch, an elderly couple strolled up to the menu board at La Petite Maison. They held hands while carefully studying the night's offerings. The signals the menu gave—yes or no, or maybe—were also quite clear.

The couple turned and strolled away from the menu board , down the hill to the village, hand in hand, their white hair bright against the shadows.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Palm House at Kew We strolled through The Royal Botanic Garden at Kew in London on a recent summer afternoon. Kew is a refuge of green in a city of grey.

For nearly three centuries, botanists have searched all over the globe to bring rare plants to the Garden, nurturing many of them in the Palm House, a giant glow worm of a building designed by English architect Decimus Burton in 1848.

Today, aircraft from all over the world threaten the peace at Kew. The flight path to Heathrow — one of the busiest airports in the world — lies directly above Kew. In less time than it takes to sniff a peony, another plane descends with earthshaking noise. I imagined passengers overhead munching on cinnamon rolls, oblivious to the noise their aircraft made as the flower before me trembled.

We stepped inside the Palm House to feel the moist rainforest atmosphere. Many of its plants are endangered or extinct in the wild. We experienced something else that is nearly extinct: silence.

Decimus Burton didn’t know about airplanes in 1848. How fortuitous, though, that he used thick glass.

1 note

·

View note