Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Golden Bamboo (Phyllostachys aurea)

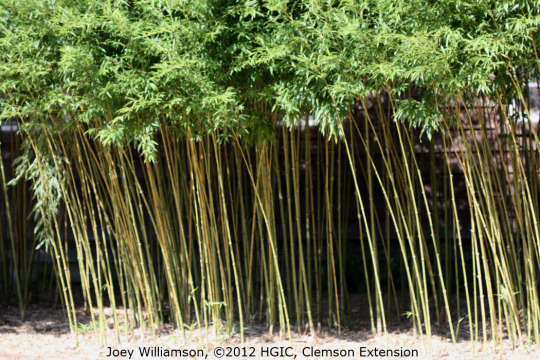

For the final post in this series I have saved the best(?) for last, or at least the worst of all the offenders when it comes to invasive species. You can really take your pick as to what bamboo species to focus on, most you find in nurseries and landscape businesses will be invasive. I have experience working with Golden Bamboo and have seen it planted at many places so I will focus on it. This species comes from China and was introduced to the U.S. as a living fence of sorts back in 1882. (Source 1) The ornamental nature of bamboo can’t be understated, it is amazing how beautiful and hardy this species of grass is. From its height, to its tight clustering, and to the pure natural aesthetic that it gives off when used for landscaping. If you can’t tell by my praise, not only is bamboo one of, if not the worst, invasive species on the planet, but it is my favorite species on the planet. (eventually I plan on getting a tattoo to display my love for the grass) Despite the fact that I love and marvel at this wonder of a plant I still recognize the fact that it is terrible to have planted at a garden or any landscape outside of its native range.

Bamboo is a very fast growing and spreading invasive, complete with cloning underground roots that make it take many treatments to fully prevent the bamboo’s return the next year. Working in a large stand of tall bamboo is very surreal and backbreaking to do, I spent many days at a site with an uphill stand of 20-foot-tall bamboo. It was also rather fun at the same time, the bamboo is light and so I would cut it at the base with my chainsaw and support it with my shoulder so it doesn’t fall, then I would get a hand under it and launch it on to the pile we were forming at the base of the hill. You do need to be careful though, vines growing on top of the bamboo can cause A LOT of tension that when released could snap a stalk off at a sharp angle and have it hurtling towards you. Also, there are dead ones littered between that can fall through onto you, but as long as you are observant and go carefully you’ll be fine. The treatment is simply cutting it down and spraying a high percentage herbicide mix on the base, the best is to get a mix of imazapyr if there are no other native species around and if you can’t then use glyphosate. At smaller sizes you can spray the leaves or cut the bases with a machete and spray the base. The best part about dealing with the removal of large bamboo stalks is that now you have a ton of great material to make stuff with! A coworker of mine and I made cups and shot glasses out of the bamboo we cut down.

As this is the last of these posts for now, I want to thank everyone for reading and I hope that you’ve either learned something, gained new insight/appreciation, or had a fun time with me on these posts.

Now for the replacements, well I actually want to have you all submit some ideas that you have for your locale. Bamboo doesn’t serve much of a purpose like a flowering bush or groundcover vine so it’s really up to personal preference and how your space is set up. As always you should look into species that are local to you and fit into your overall garden plan, whatever you have in mind and whatever fits that picture. If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- http://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/plant-directory/phyllostachys-aurea/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellate)

Autumn Olive is a large shrub that has silver leaves and produces red berries from its pale-yellow flowers in the spring. It can grow up to 20 feet tall and acts as a very nice-looking landscaping species that smells fragrant and brings wildlife to eat its berries. The species was introduced to the U.S. from Asia back in 1830 and then in the 1930s it was promoted as a way to help with erosion in disturbed sites and the berries would also attract wildlife to these sites. Both of those effects succeeded and Autumn Olive was spread through the country, unfortunately this came with the unintended consequences of its competitive abilities. (Source 1) It is an aesthetically appealing shrub to have and you will often see one or two dotting a campus or local park. When you do see it however, there is usually several others off in the woods nearby or where they stop mowing the grass.

Autumn Olive spreads quickly from the attention its berries get from animals, and then it shades out smaller plants beneath itself, not allowing them to grow. In addition the plant’s roots are able to fix nitrogen, this means the plant can live in almost any soil condition. (Source 1) With abilities to grow, survive, and outcompete such as these it is no wonder why simply replanting natives and manually removing the Olive is not enough to keep up. The species can grow to a dominant position in an area when allowed to, and the result is a monoculture of the invasive. To that end the species must be removed with proper treatments to ensure it is gone. Larger individuals will either be cut down or girdled, which means to cut a ring around the trunk and spray with strong herbicide mix to allow the tree to die without cutting it down. Smaller individuals can be cut with machetes and have the bases sprayed, or they can be sprayed on the leaves with a less potent herbicide mix if they are small enough. For large woody species like bushes or trees this technique is the standard and most basic, but that does not mean it is a catch all for all invasive species of this type.

Understanding the methods, both how to do them and why you do them allows you to gain a better grasp on how to deal with the species in question. Some invasive species like Sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata) are from the legume family and are dealt with best by herbicides made specifically for legumes (legumicide!). When I was working with spraying herbicide on Phragmites australis we worked in an area that was basically a salt marsh on the edge of the ocean. Because of the location and the large amount of water were working near we needed to use an herbicide that may have been a little less effective but was safer for aquatic animals. A lot of planning and preparation goes into the treatment of an invaded site, or I should say that it needs to go into it. I have had the unfortunate experience of working with a client after the previous one abandoned the site, only not before they fried every single plant in a section of the site. Complete with cutting one of the largest native grape vines I had seen off at the base, but this is what happens in almost any job in the world. There are those who do the job well and properly, and those who do not, and in this field you should always go for the best workers. My company that I was working for at the time are one of (if not the) best in the country and yes, they are expensive, but they will do the best job they can and do it properly.

Speaking of doing things properly, be sure to look up native species and their ranges when you are considering what species to plant. Native species need our help and every bit counts! Now for what to replace Autumn Olive with, my first suggestion is to consider one of the dogwood species. Either Redosier dogwood (Cornus sericea) or Gray dogwood (Cornus racemosa) are good ones that I know. My other suggestion is the Common Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), not only does it grow all across North America, but it is a bush (along with the dogwoods) that produces berries for wildlife. Or for you if are interested you can use the berries to make Elderberry wine. Just be sure to plant what is native and what you like!

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/indiana/stories-in-indiana/autumn-olive/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Chinese Wisteria (Wisteria sinensis)

Wisteria is an aggressively growing vine that climbs and produces beautiful purple flower clusters, depending on which species you have. Wisteria is one invasive that you don’t see too often, but when you do it has completely invaded the surrounding area. It is sometimes hard to tell that it is a vine because it will wind around itself with a thick and woody stem that can make it grow into what appears to be a small bush or tree. If you were planting it you could shape and maintain it to grow into a beautiful display without using a support structure, but we are not here to promote the sale of this plant. Unless you live in China, where the plant originates from, and where it was brought to the U.S. from in 1816 for ornamental landscaping. (Source 1) The vine is rather hardy even at a young age and it will spread across the ground and up whatever it finds.

We have talked before about the dangers that invasive vines bring, the combination of groundcover and brining down trees with the weight of the vines means that they can overrun and shade out almost all competition in an area. Along with this you typically find vines to hold on longer over other plant species, with so much area covered and connected there is often missed portions that regrow or do not get dealt enough herbicide to kill them completely. Making sure there is a clear gap around every tree trunk and that all possible leaves are hit with a coat of herbicide mix, most likely a glyphosate based broad-leaf killer. Vines are one of the most time demanding invasive species to deal with other than large bushes or trees, but obviously those do not spread or recover as quickly as vines do. I can recall days spent at sites where you would spend a couple days cutting the vines out of the trees and then have to spend another few day spraying the ground almost completely. Waterproof boots were essential for sites like those to keep your feet from turning blue, that being the blue dye we use in our mixes to let us and other people know that we have sprayed herbicide there. And if you think you’ve dealt with serious dye before, let me tell you this stuff is insane, we use so little and it still stains like crazy (it doesn’t stain plants for that long, usually several hours and then disappears from sun exposure). My boss used to say the dye was like napalm, you put a spec of it on the wall of the shower and turn the head towards it and it would be there making a blue streak for hours.

There are proper rules and regulations in place both for how to treat invasive species and how to preserve the land/native species in the area being treated. I am not an all-knowing source of these guidelines, but they are all available for you to research at your leisure online. For those wanting to know more about invasive species and the specific tactics that go into dealing with them, both the how and why, I will link one of many documents that provide a good outline for the nitty-gritty of this field. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5386111.pdf

Now, let us get into some of the replacements for Wisteria. If a flowering vine is what you are after there are many native vines to choose from, and I want to start by recommending one of my favorites. The Maypop, or Purple Passion Flower (Passiflora incarnata), is something that I discovered at one of the sites I was treating and instantly fell in love with. I mean who knew that the U.S. had a native passion flower that grows fruit and can be grown in some northern states like New York and Pennsylvania! It has a stunning flower that only opens for a few days, but it can have multiple flowers blooming from the same vine. It may take a bit of hard work to grow this guy at first, depending on where you live, but I feel it is entirely worth it. Another great native vine to consider is the Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), a good climbing vine that will attach and grow straight up whatever you give it. It has fruits to attract birds, turns a bright red in the fall, and is very hardy, needing little maintenance.

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://www.epicgardening.com/invasive-species-sold-at-garden-centers/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora)

Multiflora Rose is another of the big names when you are talking about invasive species in the U.S., as with most of the other invasive plants covered it is a highly valued landscaping species. It has solid green leaves that contrast the white flower cluster it produces nicely, also those flower clusters are where it gets the name multiflora. The other reason it is used in landscaping is because although it will appear and act like a bush, it can climb like a vine up and around any trellis you plant around it. After it attaches all you need is to trim it and there you have a beautiful rose covered archway or wall. Multiflora Rose is originally brought from China, Japan, and Korea to the U.S. in the early 1860s and was later used as rose root stock to help with rose breeding programs in the 1930s. Also during that time the USDA was encouraging people to plant it as erosion control and natural fencing from animals due to its thorns. (Source 1) This is why Multiflora rose is up there with the other big name and widespread invasive plants in the U.S.

When you are dealing with a site that have thorn baring species like Multiflora rose, Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii), Japanese hop (Humulus japonicus), or even native species like the Greenbriers (Smilax species) it makes the job a lot harder for the workers. If you have ever walked through a large bush of thorns and carefully tried to free yourself from their grasp and been left with cuts and scrapes, imagine doing that for 8 hours a day for as many days as it takes to complete that site. I’ve had serious scrapes and cuts, clothes ripped, and all manner of uncomfortable working conditions, including heat exhaustion (almost heat stroke) during my time in the field. It is to no exaggeration that the work you do in this field is hard, physically demanding, and uncomfortable in addition to the hazardous nature of working with chemicals and being out in the woods. Invasive plant removal is an unforgiving job that typically garners more negative comments than praise, not from my peers obviously, I’ve worked with and under fantastic people.

However, you see different types of people when working in public areas; those who know what you are doing and have some understanding of the importance, those who ask questions and are usually not too strongly opinioned, and those who know (or think they know) what we are doing and do not appear to understand the importance or necessity. Of these three types of people the first are the ones who smile and offer thanks or encouragement for our efforts, the second are curious but wary of our work (I always enjoyed answering questions asked in good faith), and the last are those who come up to us to talk in bad faith. These people simply write off our knowledge and experience and prefer to hold on to their own opinions of the subject. I will not say that these are bad people or call them any kind of name, it is just that they do not have the knowledge to understand what we are doing and why. If they do know and simply disagree I would hope they refrain from doing things like calling the police on us while we are working or getting large scale projects shut down.

I apologize for this turning into a pseudo-rant, but I do want to highlight the reality of working in this field. My first boss used to come into the office every day after work to remind us that we are doing good work and that we are helping to heal and return the ecosystem to its natural state. Like him I do not want the importance of this job to be lost on those reading these posts, but at the same time I do not want to understate the dangers of working with herbicides. I was given full explanations and training on the herbicides I was using and I have seen people quit when they learn more about it, but I personally felt that as long as all procedures were followed correctly there was very minimal risk. The somewhat recent case about Monsanto’s Round Up herbicide caused a big stir and produced a lot of negativity around herbicide in general, however I cannot let that be the only side to the argument. Hence why I make these posts with a large explanation of what the invasive species are like and why the herbicide is necessary to remove them.

Now as we know the best way to fight against the spread of invasive species is to not have them planted in the first place, and until I march down to Washington to demand a federal ban on invasive species we will have to get by with not planting them! Multiflora rose is only a pretty to look at plant, so I thought we could replace it with something pretty and useful, Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana). Now it is not useful in the way of getting fruit, but Witch-hazel is great if you are into making “folk medicine” or you can also make it into tea (Please do proper research first!). Speaking of plants that you can make into tea, I want to suggest another of my favorite plants to be around, and that is Spicebush (Lindera benzoin). The name comes from the great smell that this bush produces, it can be made into tea, and it looks beautiful to have in a garden. I’m picking plants that I know and enjoy but you should definitely do some research into natives in your area and find the best fit for your homes.

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://www.ecolandscaping.org/07/landscape-challenges/invasive-plants/multiflora-rose-an-exotic-invasive-plant-fact-sheet/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii)

Japanese Barberry is one that I needed to include on this list, it is probably the most common invasive species I see wherever I go in the U.S. It is planted outside of businesses, in people’s yards, or planted in town plots to add more nature to the development. Regardless of the where it is planted, the reason for its planting is because of the its ability to maintain leaves during the winter and the delightful red berries that hang off the branches. I say this but in all honesty I do not find Barberry to be a particularly appealing plant for landscaping, it has thorns and very small leaves, but maybe I’m just too sick of it to recognize its beauty. The plant is native to, you guessed it, Japan, and was introduced to the U.S. back in the late 1800s for ornamental purposes. (source 1) It does have small dangling yellow flowers that will turn into those little red berries I mentioned prior, and because they are not sought after by native species they tend to linger on the branches when the leaves are gone in the late winter.

The invasion of Japanese Barberry brought with it an unforeseen consequence beyond competing with native species, and that is its ability to function as a perfect tick nursery, habitat, and breeding ground. This phenomenon is becoming more and more well known as time goes on and more people become infected with lyme disease. Fun fact: I had lyme disease in the past and needed to take an antibiotic course for treatment, but sometimes lyme never fully leaves the body and has lasting impacts on a person. The ability for Barberry to house small animals and protect them with their thorns has given ticks a perfect place to set up and catch a ride on whatever mammal comes by. Something that is less well known to the public but I hope will become more known in the future is the combination of species like Japanese Barberry out competing native species and hugely increased deer populations causing the slow but eventual death of North Eastern forests in the U.S. Another fun fact: I am actually doing research on this and you can feel free to message me if you want more information on the subject.

As you can tell, Barberry brings one of the worst outcomes of an invasive species by creating a new temporary habitat that will cause the native to die out and then leave nothing left of the native landscape. That may seem a bit too unrealistic, but I assure you that is indeed a possible future if things are to continue as they are, and to that end I will briefly go over Barberry removal. It is a pretty standard treatment of bushes/shrubs, when it is young you can simply spray it with a low concentration Glyphosate mix, and when it is too large you can cut it off as low as possible at the base and spray the stump with a higher concentration mix of herbicide. Additionally, if you are removing it you should research at what time is best to do so. Normally before it has gone to seed and then treat the area until the plant no longer comes up, this is the standard approach to removing almost any invasive from an area.

For suggestions I had trouble coming up with some of my own because of my dislike towards Barberry, I don’t see what people like about it and so I had trouble picking good replacements. Luckily, Dr. Leonard Perry from the University of Vermont has a nice list of alternatives for Barberry that I couldn’t agree more with! https://pss.uvm.edu/ppp/articles/barberry.html Remember to always check what is native to your area and what you can grow with where you are and what kind of yard you are working with. From the ones suggested my favorite is definitely Bayberry (Myrica pensylvanica), it’s a bush that won’t grow too tall and produces white berries that used to be used to make candles. I am sure you could still do it today if you wanted, but if not, you can still walk by and enjoy the smell of the berries during the summer! Read through the list and see what you think, or just wing it and go on a hunt online or at nurseries, just make sure you’re getting the right kind of plants.

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://mnfi.anr.msu.edu/invasive-species/JapaneseBarberryBCP.pdf

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives to Burning Bush (Euonymus alatus)

Burning Bush, or winged euonymus, is another very common landscaping species seen across the country at businesses or college campuses. You’ll see it planted by towns for beautifying the public spaces or you may see it just on the side of the road or off in the woods near houses after it spread from its original planting location. It is no wonder why Burning bush is planted, even the name doesn’t do it justice I feel, it truly has a brilliant bright red display when in season and seeing the winged branches on closer inspection makes it all the more interesting to observe! Originally from Japan and China, this species was brought over back in 1860 as ornamental landscaping and remains a standard of the market to this day. (Source 1) When I say that this species is planted all over the country, I really mean it, the plant is incredibly hardy and will maintain good health without the need for much in the way of maintenance or care. This plant is mainly kept around 5-10 ft tall and used as a hedge or natural fence, but if allowed it will grow up to 20 ft tall (I do not want to deal with a 20ft tall burning bush but I’m sure it looks beautiful!).

Typically, I would see Burning Bush relatively near the location it is planted or if there is an area of dumped brush that contains branches and seeds. It is not the most aggressive spreading invasive but once it is out in an unmanaged area of forest or a green island it will spread through at a decent pace. What I mean when I say a green island is an area of land in a suburb or city that is state/county/city property and is usually not much more than a place that is undeveloped for one reason or another. I am not referring to parks but those patches of forest cover in between housing/developed areas, and when you are working in Invasive Plant Management (IPM) these areas are your typical sites. Now it will depend on who you are working for and where you are working, but I had a lot of jobs where we were contracted by the city or local government to clean up the invasive plants in these green islands.

There is something I found funny about this fact, and this is getting a bit more into what it is like to work in this field. The first being that people would be upset or dislike us spraying the invasive species there, and what is funny about that is the fact that we are being paid with their tax dollars to clean up the spread of the invasive species that they planted in their own yards. And so you can see this circle of someone buying an invasive, planting it, it spreading, a crew coming in to remove it, the homeowner getting upset about it, and the crew being paid by their tax dollars to remove the plant that they brought there. Now if you are astute you may notice how this whole exchange appears to be a bit of a waste of time and money, and could have easily been solved by not planting an invasive in the first place… and that is why I am doing this series of posts! Because this whole cycle could end if landscapers and nurseries sold only native species, and unfortunately while there are some laws that revolve around curbing the spread of invasive species there are none that prevent the sale or planting of them. What is very much needed is a federal ban on the sale, transportation, and acquisition of high-threat invasive species. I will link a quick article below that talks about Indiana’s desire to create such a law, but still there is only lip service and no real actions being taken. (source 2)

Well I didn’t end up talking about Burning Bush removal but there is plenty of resources online that explain the best practices, and I don’t have any inside info on it but you can drop me a line if you do want to know. So we can move on to the replacements for this guy, and even though I said it is not the worst invasive it should still never be used outside of its native range unless heavily managed (and even then I wouldn’t feel comfortable about it). One of my first suggestions is for a native look-a-like, the American Strawberry bush (euonymus americanus), it boasts the same red/purple leaves in the fall with the addition of beautiful small flowers that grow into fun looking pink and orange fruits! You can’t do anything with the fruits from the bush (to my knowledge), but you can plant something that will give you edible fruits. For that I would suggest a bush that I find highly overlooked in American landscaping, the Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum)! Who doesn’t want a nice-looking landscaped garden that has blueberries growing in it? (This bush will also turn red in the fall) They may be a bit difficult to grow the berries and they may take a while to produce, but if you are patient or buy an older bush you can have a great food source for you and the local birds. Whatever you chose to plant I hope you do so responsibly and make sure to try and stay native!

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://www.invasive.org/alien/pubs/midatlantic/eual.htm

Source 2- https://www.invasive.org/alien/pubs/midatlantic/eual.htm

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana)

Callery Pear goes by many names and comes in many varieties, but the most commonly known is the “Bradford” pear. The reason for the varieties comes from the fact that this species has been widely planted as landscape trees and horticulturists have enjoyed crossbreeding new varieties. The species was first introduced to the U.S. back in the early 1900s for landscaping purposes, it is native to areas in China and Vietnam. This species is loved for its ability to maintain a relatively small size and keep its leaves green for a good part of the year. Additionally, it produces beautiful white flowers that can cover the entire tree when they bloom in the spring before the leaves emerge. Making the trees stand out as entirely white, as if covered in snow! It truly is a manageable and beautiful tree that’s perfect for landscaping, and that is why it has become such a prolific invader in the U.S.

Normally the species that is used is sterile and will not spread, however, it can breed with other similar species or be planted with fertile root stock that allows the tree to become fertile and then allows its offspring to spread as they please. (source 1) This species is still unfortunately being sold at a high rate for landscaping despite the fact that many people are reporting on the invasive nature and the destruction of local habitats that it causes. The Callery pear is a classic situation of an invasive species that is able to grow, reproduce, and shade out all other native competition in an area. I have encountered Callery pear at many of the sites I’ve worked at that are both small saplings and full-sized trees two stories tall. Standard procedure is to cut down the trees with a chainsaw and spray the stump with a high percentage (about 10%) herbicide to ensure the tree doesn’t have stump sprouts or shoot back up. I find the ability of invasive plants to survive despite everything we throw against them both remarkable and a cruel joke because of how much I must struggle to keep some of my plants alive.

I talk about herbicide a lot in these posts and that is because it is honestly the most effective tool for removing invasive species from a site. People like to imagine that you can simply use mechanical methods in combination with native plantings to revitalize an area and move the invasives out. While that can be possible at select sites, it is very much a pipe dream in my opinion. A large amount of invasive species come to an area and are able to invade and take over while the ecosystem is functioning at its normal level. This alone should make you see that native species cannot compete with invasive species most of the time. Meanwhile you can have mechanical removal projects but there are several limitations and drawbacks to doing so; the main being the time needed, the amount of manpower, and the scale of the project. I will add a photo below this of an area that I thankfully did not work in that had been 100% invaded by Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobate), a vine that will destroy an entire forest on its own if allowed to.

Well regardless of how you feel about how the invasive species are removed, the most important part is making sure we have the right native species growing back in their place and maintaining a healthy ecosystem! Since the species of discussion here is supposed to be a fruiting tree, or at least a flowering one, you can really look into what species or fruit you would want to have planted around. I always recommend checking for what is native around you, and my first suggestion is to grow a crabapple because they are the only species of apple native to North America! Despite our country being know for apple pie we originally only had crabapples like the Native Sweet Crabapple (Malus coronaria), but I mean tomatoes aren’t native to Italy so who cares. There are many uses for crabapples if you want them for cooking, but if you are more interested in a flowering tree only than the Cockspur Hawthorn (Crataegus crus-galli) is what you want. Some people don’t want to deal with trees that produce large fruit and that’s fine, the crabapple does produce beautiful flowers, but you do need to deal with the apples. The Hawthorn has a very large range so most people will find this species native in your area, and it produces beautiful showy white flowers and has persistent small red fruits! Whatever kind of role you want to have filled with your plants just be sure to keep them native to your area, both for the benefit of your local ecosystem and the species that live in it.

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

(Source 1) https://www.invasiveplantatlas.org/subject.html?sub=10957

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Common Reed (Phragmites australis)

Phragmites, or “Phrag” as it is often called, is not one of the plants that gets introduced to the U.S. for the purpose of planting in gardens and landscaping. Phrag (after working with it so much I always just call it Phrag) is the more typical type of invader. It is believed to have arrived as ballast on ships coming from Europe in the late 1700s to early 1800s. (Source 1) While this current species of Phragmites is an invasive nuisance, there are records of a native species that permeated most of North America for thousands of years. Because it is not mainly spread through the landscaping market, there is more labor that needs to go into stopping the spread and reducing its grip on landscapes. This post is less about how to replace this species, unless you own a plot of land with Phrag on it, and more a view into what a serious invasive species is capable of and how to deal with it.

As its name suggests it is a common reed that is found in areas where there are higher levels of water saturation in the soil. Meaning mostly the edges of streams and in wetland areas, or that’s what would be typical at least. As long as there is enough water while the plant is growing it is capable of growing almost anywhere and in almost any soil. This species ranges all the way up to northern Canada and reaches down into southern Texas, it really only needs water. Where you would be most likely to see this plant is in your car going down the highway, areas of high human traffic spread invasives easily and roads cause a lot of excess runoff and pooling around the sides. Major roadways that have poorly maintained/ not well manicured edges can very easily be filled with Phrag for miles.

Not only is Phrag a very prolific invasive, but it is very difficult to remove from a site completely. My first job in the field of Invasive and Exotic plant removal was working with almost nothing but Phrag for about 3 months. If anyone has experienced working with this plant they will tell you that it is not a pleasant experience. Most people I met thereafter would be surprised and remark at how bad their own experiences with it were. There are a few reasons as to why this species is so difficult to deal with, number one being its rhizomes. What rhizomes do is very similar to a root, it serves as the base of the plant and extends in/along the ground to absorb water and nutrients. The problem comes with the fact that the rhizomes can spread as far as they want and sprout any number of shoots up while they go, and so even if you think you’ve sprayed an area there can still be rhizomes underneath nearby native species or stretched out meters away from the shoots. We would usually spray any surface rhizomes we found to help spread the intake of herbicide to the plant, the rhizomes can form a sort of colony and at times if you spray the reeds the herbicide may not absorb into the whole system. The second aspect that is very difficult to deal with is how dense the stands of reeds can get with these colonies, and also how tall they are. The species can reach heights of 15ft and spraying into these stands is both uncomfortable and hazardous for the applicator. When necessary applicators will need face shields and full suits of protective clothing to make sure they aren’t being covered in the herbicide as they move through the reeds. When an area of land is very heavily invaded by Phrag there is often a call for prescribed burnings in that area to help cut down the amount of Phrag and give native species a chance to repopulate. However, the third aspect of what makes this species hard to remove is the fact that it is very hardy and needs several years of treatment to ensure it is removed (this is not an uncommon facet of invasive plant removal, but I find Phrag holds on much longer than others). I did not go much into detail on how this species is bad for the areas it invades, but I feel that my descriptions of dealing with it form a clear picture of what this species does to a landscape.

The University of Texas at Austin Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center gives recommendations as to what plants can be grown in same type of habitats as Common Reed; Inland Sea Oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) is a short clumping native grass whose leaves will turn bright yellow in the fall, Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) is a milkweed species that lives in wetlands and has large deep pink flowers that form large clusters. As always with picking out native species to plant you should refer to your specific location and native species, feel free to search the USDA or other sites for what species live in your area.

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://www.invasive.org/alien/pubs/midatlantic/phau.htm

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for English Ivy (Hedera helix)

English Ivy is one of the most common plants bought for landscaping and is prolific in its spread across the U.S. Originally introduced to the county back in 1727, it has been used as a groundcover species that requires little to no management and stays green throughout most if not all of the year! (Source 1) It should be of no surprise that English ivy is a popular plant for a homeowner to have growing over the bald spot in their grass or climbing up a brick chimney on an older house. It is a beautiful vine that comes in many varieties, can survive in almost any condition, and is very tolerant to changes to its habitat. Very much a set it and forget it type of plant. However, while caring for the plant may be an easy and laid-back process, English ivy is one of the most aggressive invasive species in the U.S. when it comes to spread and take over. (Source 1)

English ivy is a groundcover vine that chokes out all competition under a canopy due to its ability to spread and thrive in almost complete shade. When I would see a site like this, we would call it a “carpet” because its actually just covering the ground completely. These ivy mats also allow for water to pool and stagnate more often, creating mosquito habitats. English ivy does not relegate itself to staying on the ground however, it is able to climb up chimneys and trellises when planted near them. What happens when it encounters a tree then? Or an entire forest? Well it climbs and climbs and spreads out until the tree is no longer visible. Not only does this strangle-hold block light or the ability of the tree to survive, but it causes a major issue and risk for areas where this occurs near construction or people. The tree being dead and covered with hundreds of pounds of vines will either fall all together or in parts, damaging anything around it.

The treatment for an English ivy carpet is what we would call “carpet spraying,” basically holding down the trigger and pumping the backpack sprayer constantly to cover the leaves with a sheen of a broadleaf herbicide like Triclopyr (usually for 2 or more times for full treatments). For the vines that have climbed into the trees you need to cut all the roots around the tree and treat with a strong herbicide mix. It is difficult for a site to come back from a full cover of English ivy, and because of the need to spray so much, it is difficult for a worker to avoid the one in one hundred native species poking out through the ground. The ivy is very resilient but when done correctly the site will turn into a brown and “crispy” floor. A lot of times when you are working on the ground at sites such as these (or any for that matter) you will encounter people scolding or upset that you have killed all the beautiful green life that was originally there, and this is something you need to be prepared to deal with.

But I will talk about that in another post, for now we can look at the native alternatives available for planting instead of English ivy! As always these will depend on your location, so be sure to look into what your state has for native species, you may even find some that they are trying to help grow more of and so you can assist them by offering your land! The Philadelphia Water Department lists several great species for either climbing or groundcover vines. Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), is a great native climber that boasts beautiful dark green leaves with long orange to red flowers that bloom during the summer. The Blue phlox (Phlox divaricata) is a nice groundcover species that has blue flowers blooming in the spring that will attract hummingbirds and butterflies. They are great for filling out garden space in between rocks or on the edges of grass. Check out this and the other links for more info on English ivy and what to replace it with! https://pecpa.org/wp-content/uploads/9-Invasive-Species_English-Ivy.pdf

If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1 https://www.invasive.org/alien/pubs/midatlantic/hehe.htm

1 note

·

View note

Text

Replacing Invasives! Native Alternatives for Mimosa trees (Albizia julibrissin).

Mimosa is a beautiful flowering tree that is native to parts of Asia and was first introduced to the United States back in 1745. (Source 1) This tree species has been widely used as an ornamental along roads and in people’s yards since its introduction and today it is still sold and planted for its showy pink flowers that bloom during the summer months. Typically, this species is seen in more southern states, but it can still be found all the way into southern Maine! Looking at this tree it is no wonder why it is planted for ornamental purposes, however, it is listed as serious threat in most of the states that it thrives in.

Some may find it hard to consider a simple and beautiful flowering tree as a threat to anything other than a small plant trying to grow in its shadow, but let it be known for those who are not aware, invasive species are a real threat to the ecology of this country and the world. That may sound hard to believe and a little over exaggerated but the Mimosa along with many other non-native invasive species, are taking over and causing damage to ecosystems all across the U.S. This is simply my opinion on the subject, if you go to the Department of the Interior’s website they have a large amount of effort being put into the slow down and removal of invasive species in this country. https://www.doi.gov/invasivespecies

Dealing with these already established invasive plants requires two major factors, that being money and man hours. Unfortunately, we find that with most of the high-level threat invasives that they are too strong of a competitor and push out all but other invasive species from our local ecosystems. I have personally had multiple jobs working in invasive plant removal and hold a degree in environmental science, so you can trust me on this too. When removing a Mimosa tree, first there are usually a large stand of them in most areas you would find them, you will take a machete most likely and hack vertical slashes into the trunk at an angle all around the base. The next step is to use a somewhat high concentration of glyphosate (about 5-10% for larger trees) in a mixture with water and spray that into the hacks made in the tree. Please do not simply try this at home, I am summarizing the techniques used by licensed pesticide applicators. The goal is to cut into the tissue of the plant that transfers water and nutrients (the xylem and phloem) to spread the herbicide through the whole plant to kill it entirely. Other options are to simply chainsaw it down at the base and spray the herbicide on the stump or to spray a less concentrated mixture on the leaves of young plants.

Regardless of whether or not you have Mimosa planted on your property, we could all do a big service to our local ecosystem by planting native species instead of non-native ones. Not only does the spread of native species help the local environment, but these species are specifically adapted to live in the areas you are planting them in. That usually means less watering and maintenance in order to keep them happy and healthy, along with better survival through the cold/heat! You can look to see if your state, local national park, nursery, or neighbor knows of any native replacements for the non-native species you grow or typically see around.

The Georgia Exotic Pest Plant Council has a large list of native replacements for the Mimosa and other invasive tree species such as: Red Maple (Acer rubrum), Serviceberry (Amelanchier arborea), Pagoda Dogwood (Cornus alternifolia), and many more!

In my experience when you look into what native species you could grow you would be shocked to find that some of the most beautiful plants are growing so close to you! I love finding out that plants most people call weeds and run over on their lawnmowers are actually some of my new favorite plants to grow! If you want to know more or want to share pictures from your gardens feel free to message me and we can talk about plants!

Source 1- https://www.gainvasives.org/species/Albizia-julibrissin/

https://www.nps.gov/depo/learn/nature/invasives.htm

2 notes

·

View notes