Text

Projects: Pacific Standard

I’ve worked as the editor-in-chief of Pacific Standard since June of 2015 (after serving as the digital director since April of 2013 and as the associate publisher of The Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media, and Public Policy, the non-profit parent of Pacific Standard, from March of 2014 through June of 2015).

As the editor-in-chief, I direct editorial strategy for the National Magazine Award-winning print magazine and daily website while growing circulation and increasing print frequency from six issues/year to eight; supervise a full-time editorial, art, and production staff of 15, as well as dozens of on-contract contributors and hundreds of freelancers; work with the president, publisher, and marketing team to create new products, special sections—both in print and online—events, and more; serve in an advisory role to several other Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media, and Public Policy partners, including the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, the University of California–Berkeley Social Science Matrix, the American Academy of Political and Social Science, and others.

By combining research that matters with ambitious narrative and investigative reporting, Pacific Standard tells stories across print and digital platforms about society’s biggest problems, both established and emerging, and the people attempting to solve them.

By combining research that matters with ambitious narrative and investigative reporting, Pacific Standard tells stories across print and digital platforms about society’s biggest problems, both established and emerging, and the people attempting to solve them.

Our publications include a bimonthly print magazine and a dynamic website, PSmag.com. In partnership with our parent organization, the non-profit Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media, and Public Policy, Pacific Standard works with national organizations focused on the social and behavioral sciences, bringing public discussions to live audiences.

The Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media, and Public Policy is a non-profit organization that strives to not just inform, but also to promote meaningful dialogue by reporting, in clear and concise language, the latest and most relevant scientific research and innovations shaping the issues of the day. Today, using print and online resources, internships, and direct outreach to the scholarly community, the Center is planning for a broader future, including the expansion of its programming and collaborative initiatives. The Center’s goal is to tap into existing research to inform and promote forward-thinking actions in public policy, especially in the areas of economic, educational, environmental, and social justice.

Letters

Letter From the Editor: The Future of Work and Workers (September/October 2015)

Letter From the Editor: Toward a Bridge Across the Skills Gap (November/December 2015)

Letter From the Editor: What You Could Buy With $60 Billion of Missing Medicare Funds (January/February 2016)

Letter From the Editor: Our Best Hopes for a Brighter Future (March/April 2016)

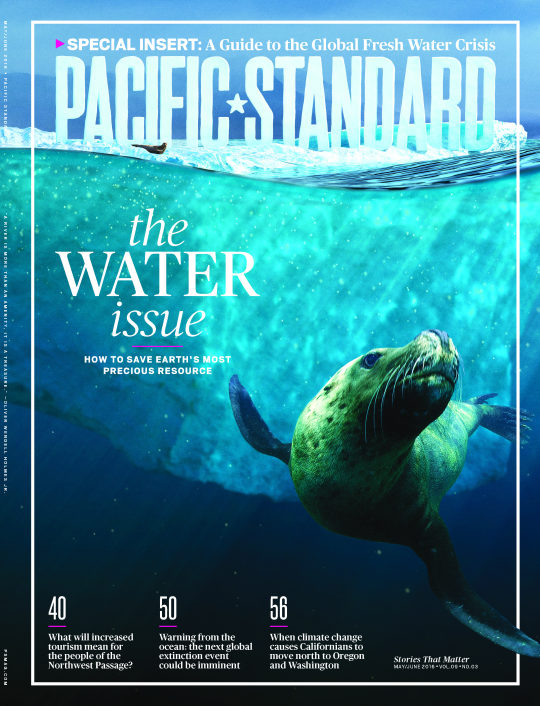

Letter From the Editor: The Water Issue (May/June 2016)

Letter From the Editor: Introducing the New ‘Pacific Standard’ (July/August 2016)

Letter From the Editor: Our Fragile Food System (September/October 2016)

Letter From the Editor: The End of Captivity (November/December 2016)

Letter From the Editor: The Year Ahead (January/February 2017)

Letter From the Editor: Our Commitment to Readers (March/April 2017)

Select Clips

Introducing the ‘Pacific Standard’ Re-Design (Pacific Standard, 2016.06.05)

Why Do We Hurt Each Other? (Pacific Standard, 2013.04.15)

Churnalism Sorts Original Journalism From Repackaged Press Releases (Pacific Standard, 2013.04.23)

Once and for All: Gay Marriage Is Not Bad for Kids (Pacific Standard, 2013.06.26)

Issues as Editor-in-Chief

Pacific Standard: Volume 8, Number 5 (September/October 2015)

Pacific Standard: Volume 8, Number 6 (November/December 2015)

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 1 (January/February 2016)

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 2 (March/April 2016)

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 3 (May/June 2016)

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 4 (July/August 2016)

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 5 (September/October 2016)

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 6 (November/December 2016)

Pacific Standard: Volume 10, Number 1 (January/February 2017)

Pacific Standard: Volume 10, Number 2 (March/April 2017)

Pacific Standard: Volume 10, Number 3 (May/June 2017)

Re-Design

Pacific Standard: July/August 2016 Re-Design

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pacific Standard: July/August 2016 Re-Design

Before

After

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 10, Number 3 (May/June 2017)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 10, Number 2 (March/April 2017)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 10, Number 1 (January/February 2017)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 6 (November/December 2016)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 5 (September/October 2016)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 4 (July/August 2016)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 3 (May/June 2016)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 2 (March/April 2016)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 9, Number 1 (January/February 2016)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 8, Number 6 (November/December 2015)

0 notes

Text

Pacific Standard: Volume 8, Number 5 (September/October 2015)

0 notes

Text

Clips: Why Do We Hurt Each Other? (Pacific Standard, 2013.04.15)

Shortly after reports started coming out — from professional journalists and citizen reporters alike — that two explosions had gone off in downtown Boston this afternoon near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, the world’s oldest annual marathon and one of the most high-profile road-racing events anywhere in the world, my friend and former colleague, Max Fisher, now the foreign affairs blogger for The Washington Post, tweeted out a message from his sister, a runner, that got me thinking.

“I have been running long distance events for many years and every time I go by a crowd I get that thought, someone could hurt me right now, this is just such a vulnerable position,” she wrote.

I get that thought a lot.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been a little frightened by dark streets or unfamiliar places. When my mother told me about the neighborhood friend of hers who had to hold an intruder — drunk and shirtless, he broke through her basement window in the middle of the night before ascending the stairs toward her bedroom — at gunpoint until the cops showed up, I added my own home, at least when empty except for myself, to the list of scary places. And even in broad daylight, at least since that time I was mugged on the streets of Washington, D.C., at 6 p.m. by three men, I’m not particularly fond of passing someone I don’t already know on the sidewalk.

Some might say I’m not a very trusting person. But you guys haven’t given me a lot of reason to be. We hurt each other, all the time. The biggest predator of humans? Other humans.

Since the explosions were first reported, I haven’t been able to turn myself away from Twitter. It’s important to remember, as Charlie Pierce was quick to point out, that “nobody knows anything yet.” (And credit to Jake Tapper for noting, on CNN, that initial reports are almost always wrong — or at least not fully right.) Small details are starting to be verified (or at least corroborated) as the afternoon wears on — a couple dead, spectators near the finish line giving up their belts to staunch the flow of blood from missing limbs, dozens injured, the first explosion was probably a small homemade bomb placed in a trash can — but I’m interested in the bigger details. The small details will get sorted out, as they always do; the sidewalks will be cleaned; and we will mourn, as we should.

But just as many hoped the Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting that left 26 dead in Newtown, Connecticut, would be a catalyst for a larger discussion about gun violence, I’m left sitting here wondering how things like this happen in the first place. (Citing a “special significance” to the fact that the number of people killed in Newtown matched the number of miles in a marathon, Boston Athletic Association president Joanne Flaminio announced last week that the city would honor the victims with a special mile marker — the city’s seal surrounded by 26 stars, one commemorating each life lost — at the end of the race’s 26th mile. Eight people from the community participated in the race, while a family from Newtown sat in the VIP section near the finish line. Reports say none were injured.)

Set aside the possibility of a police scan of every garbage can within a 10-mile radius of upcoming major events. Or the idea that we can put an end to violence by adding more metal detectors to the entrances of public buildings or scanners to our nation’s airports. (As far as I know, my muggers in D.C. didn’t have a knife or a gun, nothing that could have been taken or confiscated; a surprise attack and a couple of big boots to the back of the head is enough to convince just about anyone to give up his or her wallet.) We’re too often focused on technological solutions to stopping individual acts of crime, instead of attempting to identify — and fix — underlying societal problems. I want to know this: Why do we hurt each other?

It’s not a new question, of course. In fact, it’s a question with more answers to it than any other I can think of right now (though, admittedly, it’s hard to think of much else at the moment), a question that will be answered over and over again. It’s a question that experts across all disciplines in the social and behavioral sciences are studying — historians, criminologists, psychologists, and more — and we’ll continue to showcase their latest research and findings every day here at Pacific Standard as we seek to shed light on (and, when possible, propose solutions for) society’s biggest problems. And it’s a question that requires lots of answers, because, let’s not forget, all violence is not equal. Our courts make that clear. A violent action is the result of a complex cocktail of circumstances, and can be influenced by mental illness, drugs, feelings of revenge or retribution — or something else entirely.

Given all of that, physicists will probably reconcile quantum mechanics and general relativity long before social scientists are able to boil down the nature of violence into a couple of neat takeaways — but I thought I would try by starting with a quick survey of some of the things we know we know. Because today, I need some answers.

Alcohol and Violence

More than probably anything else, alcohol has been closely tied to violence. Not only are people who consume alcohol more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior, but people who are the victims of violence are more likely to consume alcohol in excessive amounts. That’s true, too, for children and young adults. A report released in the U.K. found that “around half of violent crimes [in 2004] were thought to be committed while under the influence,” according to The Guardian. And almost 25 percent of assaults took place in or close to bars and pubs.

Desensitization and Violence

Even if you’ve never fought in a war, you know the sound an automatic weapon makes. I suspect you would even be able to figure out how to load and shoot one if the need arose. Numerous studies — conducted by the Surgeon General, the American Psychological Association, and the National Institutes of Health, and most often cited by those making the case that violent video games are damaging our fragile children — have shown that a desensitization to violence (by the time a child in the United States reaches the age of 18, he or she will have witnessed 200,000 acts of violence on television or in the movies, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics) makes us perceive actual violence as more acceptable.

Detachment and Violence

We know this instinctively — perhaps because almost all of the recent media-covered perpetrators of violence (the James Holmeses and Adam Lanzas) fit the stereotype — but studies confirm that those who are marginalized or isolated or otherwise without strong social connections tend to be more violent. When we don’t share ties to others, we care less about their well-being. When we exist as part of a strong social network or community, aggressive thoughts and actions are reduced.

Genetics and Violence

Several studies have tied biological factors to aggressive behavior. A team at the University of North Carolina made headlines back in 2008 when their research found that people with a specific variation of the MAOA gene were far more likely than others to participate in criminal activity. “I don’t want to say it is a crime gene, but one percent of people have it and scored very high in violence and delinquency,” Guang Guo, the sociology professor who led the study, told Reuters. Guo was hesitant to call it a crime gene, because it’s generally understood that neither biological or sociological factors alone can be directly linked to aggressive behavior.

I can go on. There are a lot of studies about the psychology of violence, all of them attempting to push our understanding forward just a little bit further. But no matter how many of them I’ve read — both prior to this afternoon and since the bombing — I keep coming away with the same old adage, a line that has been widely adopted, it seems, by the family therapy crowd: Hurt people hurt people. And any feeling that is felt strongly enough will find a way to be shared — whether we want it to be or not.

It seems too simple — and it is. But for right now, that’s all I need.

The note that Max Fisher posted by his sister, the runner? It ends like this: “Then you remember that marathons are a time of unity and celebration and no one would do that. I have five friends running the Boston right now. I hate having to text them anything but congratulations.”

0 notes

Text

Clips: Churnalism Sorts Original Journalism From Repackaged Press Releases (Pacific Standard, 2013.04.23)

“This is just a repackaged press release.” That’s one of the most common complaints about the way that most media outlets cover the social and behavioral sciences — and even the hard sciences, really.

The primary reason for that? Most working journalists have a limited understanding of many of the subjects they’re often asked to write about. I would even argue that this — the ability to explore and report and write about something new every day — is a key motivator for many of us in the profession. (It’s certainly why I dumped my early ambitions of working as a particle physicist. Quarks, all day? No thanks.) The problem, of course, is that as budgets and revenue streams shrink and sometimes disappear altogether, those of us left standing have been forced to do more, faster. And the first thing that falls away from that list — explore and report and write — is the reporting.

And we turn to others to do the work for us.

That’s how you end up with churnalism, the process of regurgitating press releases. “You get copy coming in on the wires and reporters churn it out, processing stuff and maybe adding the odd local quote,” BBC journalist Waseem Zakir, who is widely credited with coining the term, told Tony Harcup for his 2004 book, Journalism: Principles and Practice. “It’s affecting every newsroom in the country and reporters are becoming churnalists.” (Unable to obtain a copy of Harcup’s book on short notice, I took that passage from the Churnalism page on Wikipedia, but I checked it against multiple references, including a 2011 Martin Robbins column for The Guardian and the blog of Jon Slattery, who has written about churnalism on at least a few occasions over the last five years.)

A new tool released today by the Sunlight Foundation, a non-profit obsessed with openness and transparency, promises to call greater attention to this “work.” Accessed through a stand-alone site or used as a browser extension, Churnalism compares any text against its database of documents, which includes a majority of the Wikipedia archive and press releases from PR News Web, PR Newswire, EurekaAlert!, and “a sampling of Fortune 500 companies,” among many other sources, according to an explainer from Sunlight’s Nicko Margolies. (Full YouTube tutorial embedded below, with technical details from Drew Vogel, one of Churnalism’s developers, available here.)

youtube

When the tool detects a “churn,” you’ll be able to compare the two texts side-by-side, with passages that appear to be copied verbatim highlighted and easy to track. Here’s an example of a story that ran this past October on NBCNews.com (though it originally appeared on Universe Today). You can see that the majority of the second half of the story was repurposed from a EurekaAlert! press release. Earlier today, Web developer Kaitlin Devine explained to The Atlantic’s Rebecca Rosen (a former colleague of mine) that science press releases tend to be plagiarized more often than others. “[T]he language around the findings in those is so specific that it becomes very hard to reinterpret it,” Devine offered as one possible explanation.

I don’t see any real issue with using a press release as a starting point for an article. They point us to very real discoveries, summarize the findings of important studies, and alert us to new and important work. But we must keep in mind, always, that they are marketing materials. The press release mentioned in the example above? It was distributed by the Carnegie Institution and told of exciting new work from a team of astronomers led by … the director of the Carnegie Observatories. It mentioned the Carnegie Institution or Carnegie scientists no fewer than six times. In “reinterpreting” that release for Universe Today, the “writer” only mentioned Carnegie once, but she didn’t bother — it appears — to question or challenge any of the information fed to her.

And I’m OK with that, too. There are other ways for a journalist to add value to a story: by conducting original reporting, placing the material provided by the press release in a larger context, inserting an informed opinion. What I’m not comfortable with is the complete lack of transparency. At no point in the Universe Today story is it noted that the quotations used, and the information presented, were obtained through a single press release. Even if the story wasn’t questioned, didn’t add context, and was without opinion, readers would know how to interpret it — and could determine for themselves how much to believe. Above all, trust the intelligence of your reader. Especially now, because, thanks to the Sunlight Foundation and Churnalism, they can find you out.

A Note About Pacific Standard: Our goal here is to make the latest findings and big ideas from the social and behavioral sciences accessible to a wide audience. Because of that, we’re constantly receiving and sifting through press releases — from government agencies, university departments, and others — so we’re certainly not immune to criticism related to churnalism. Know, though, that we make a conscious effort to slow ourselves down and find the places we can add value, to read the original studies and compare them to the body of work, and to be selective about what we cover and how we cover it. Before I started writing this, I ran a bunch of our recent pieces through Churnalism. So far, we’re clean.

0 notes

Text

Clips: Once and for All: Gay Marriage Is Not Bad for Kids (Pacific Standard, 2013.06.26)

When the Supreme Court struck down the 16-year-old Defense of Marriage Act on Wednesday morning as part of a pair of decisions that amount to a major victory for the gay rights movement, they also killed the argument that gay marriage is bad for children.

DOMA supporters have long claimed that kids are far better off when they have both a mother and a father at home. (They even go so far as to quote from a 2008 speech by President Obama, who supports same-sex marriage, in which he emphasized the role of fathers; “Of all the rocks upon which we build our lives, we are reminded today that family is the most important. And we are called to recognize and honor how critical every father is to that foundation,” he said.) Just last week, Representative Phil Gingrey (R-Ga.), the leading Republican candidate for a Senate seat in Georgia, told House colleagues on the floor that children would be better off is they were required to take classes on traditional gender roles.

“You know, maybe part of the problem is we need to go back into the schools at a very early age, maybe at the grade school level, and have a class for the young girls and have a class for the young boys and say, you know, this is what’s important,” he said. Speaking in defense of DOMA ahead of the Supreme Court decisions, Gingrey noted that, while he understands that the “father knows best” adage is dated, he still believes in it.

But Gingrey is not alone in subscribing to ideas from “back in the old days of television,” as he puts it. The argument that the children of same-sex couples are negatively influenced by the family structures in which they are raised came up multiple times during the oral arguments for this case. This, from an amicus brief of “social science professors” submitted to the Supreme Court: “With so many significant outstanding questions about whether children develop as well in same-sex households as in opposite-sex households, it remains prudent for government to continue to recognize marriage as a union of a man and a woman, thereby promoting what is known to be an ideal environment for raising children.”

As noted in a piece for The Atlantic by Philip N. Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland-College Park (and sometimes contributor to Pacific Standard partner site Sociological Images), Justice Antonin Scalia returned to the 40-plus-page brief later: “[T]here’s considerable disagreement among sociologists as to what the consequences of raising a child in a single-sex family, whether that is harmful to the child or not,” he said. Scalia would go on, along with Justice Samuel Alito, to write a dissent to today’s court ruling, and even read it from the bench, “a step justices take in a small share of cases, typically to show that they have especially strong views,” the New York Times reported.

Scalia might have especially strong views, but that doesn’t mean they’re right. Or even that they have support.

The problem? That brief was found to be based on severely flawed studies. Over at his Family Inequality blog, Cohen runs through all of the evidence. It’s a fascinating story, as Cohen puts it, “of how Christian conservatives used big private money to produce knowledge in service of their political goals.”

In fact, there isn’t considerable disagreement among sociologists. As we note in the Five Studies column from our current July/August issue, this one on how we have thought about homosexuality over the past 150 years, “by now virtually all of the major psychiatric, psychological, sociological, and pediatric professional organizations have officially declared that ‘being gay is just as healthy as being straight,’ as the American Psychological Association puts it. That goes for the children of same-sex parents too.”

Also cited in amicus briefs put before the Supreme Court earlier this year was a meta-analysis by Cambridge University psychologist Michael Lamb of more than 100 studies over the last three decades. Lamb’s research concluded that “the children and adolescents of same-sex parents are as emotionally healthy, and as educationally and socially successful, as children and adolescents raised by heterosexual parents.” It was likely this research to which Kennedy was referring when he wrote, in today’s majority opinion (5–4), that DOMA “places same-sex couples in an unstable position of being in a second tier marriage. The differentiation demeans the couple, whose moral and sexual choices the Constitution protects, and whose relationship the state has sought to dignify. And it humiliates tens of thousands of children now being raised by same-sex couples.”

If it wasn’t those briefs, then perhaps Kennedy is familiar with the latest sociological research on the subject. While not as comprehensive as Lamb’s meta-analysis, a look at 500 children between the ages of one and 17 as part of the Australian Study of Child Health in Same-Sex Familiar found that children with same-sex parents are actually healthier than those with opposite-sex parents. “Because of the situation that same-sex familiar find themselves in, they are generally more willing to communicate and approach the issues that any child may face at school, like teasing or bullying,” lead researcher Dr. Simon Crouch, a public health doctor and researcher at the University of Melbourne’s McCaughey VicHealth Centre, told The Sydney Morning Herald. “This fosters openness and means children tend to be more resilient. That would be our hypothesis.”

Father knows some things, certainly. But he’s not the only one who knows how to raise happy, healthy children.

0 notes

Text

Projects: The Atlantic

I worked as an associate editor at The Atlantic from September of 2010 through April of 2012. In this role, I oversaw all health, food, and alcohol content for TheAtlantic.com as the founding editor of the site’s Health channel, which I launched and quickly turned into the most-trafficked section of TheAtlantic.com; worked with dozens of freelance writers to edit and run approximately 60 stories per week. Prior to launching the Health channel, I maintained the site's Life section, which covered design and environmental issues, among other things, and was part of the two-person team that launched TheAtlantic.com's Technology channel and wrote the strategy that became The Atlantic's multi-person video production unit.

The Atlantic is an American magazine, founded in 1857 as The Atlantic Monthly in Boston, Massachusetts. Since 2006, the magazine is based in Washington, D.C. Created as a literary and cultural commentary magazine, it has grown to achieve a national reputation as a high-quality review organ with a moderate worldview. The magazine has notably recognized and published new writers and poets, as well as encouraged major careers. It has published leading writers' commentary on abolition, education, and other major issues in contemporary political affairs. The periodical has won more National Magazine Awards than any other monthly magazine.

The first issue of the magazine was published on November 1st, 1857. The magazine's initiator and founder was Francis H. Underwood, an assistant to the publisher, who received less recognition than his partners because he was "neither a 'humbug' nor a Harvard man". The other founding sponsors were prominent writers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Greenleaf Whittier, and James Russell Lowell, who served as its first editor.

After experiencing financial hardship and a series of ownership changes, the magazine was reformatted as a general editorial magazine. Focusing on "foreign affairs, politics, and the economy [as well as] cultural trends," it is now primarily aimed at a target audience of serious national readers and "thought leaders." In 2010, The Atlantic posted its first profit in a decade. In profiling the publication at the time, The New York Times noted the accomplishment was the result of "a cultural transfusion, a dose of counterintuition, and a lot of digital advertising revenue."

Select Clips

Who Is Behind Susan G. Komen’s Split From Planned Parenthood? (The Atlantic, 2012.02.01)

How Osama Bin Laden’s Low-Tech Compound Gave Him Away (The Atlantic, 2011.05.02)

How the Life-Saving Blue Blood of Horseshoe Crabs Is Extracted (The Atlantic, 2011.06.30)

Racing to the Bottom: Exploring the Deepest Point on Earth (The Atlantic, 2011.07.26)

Shark Week: Remembering Bruce, the Mechanical Shark in ‘Jaws’ (The Atlantic, 2011.08.03)

Even Disney Doesn’t Know How to Build a Profitable Web Business (The Atlantic, 2011.08.10)

Maybe a Second AOL-Time Warner Marriage Would Work Better (The Atlantic, 2011.08.11)

To Be the Most Powerful Gay Man in Tech, Cook Needs to Come Out (The Atlantic, 2011.08.25)

Introducing The Atlantic’s Health Channel (The Atlantic, 2011.12.13)

Christopher Hitchens Dead at 62 (The Atlantic, 2011.12.16)

Will Readers Pay For an All-Access Media Pass? (The Atlantic, 2010.09.15)

What Motivates Amazon’s Hardcore Raters? (The Atlantic, 2010.09.27)

Why Groupon Shouldn’t Get Into the Business of Big-Ticket Items (The Atlantic, 2011.07.14)

Mousetraps: A Symbol of the American Entrepreneurial Spirit (The Atlantic, 2011.03.28)

The Tech That Could Help Save Fukushima: Putzmeister 70Z-Meter (The Atlantic, 2011.04.28)

Last Typewriter Factory in the World Shuts Its Doors (The Atlantic, 2011.04.25)

Google’s Disappointing Decision to Hide Its Support of Gay Pride (The Atlantic, 2011.06.20)

Bill Simmons’s Grantland Is Doomed Even Before Launch (The Atlantic, 2011.06.08)

Museums Battle for One of NASA’s Retiring Space Shuttle Orbiters (The Atlantic, 2011.03.30)

Jack Kevorkian’s Death Van and the Tech of Assisted Suicide (The Atlantic, 2011.06.03)

The First Photograph of a Human (The Atlantic, 2010.10.26)

TED Speakers Imagine a World Controlled by Women (The Atlantic, 2010.12.07)

What You Need to Know About the New York Times’ Pay Wall (The Atlantic, 2011.01.24)

Investors Overvalue Demand Media in Initial Public Offering (The Atlantic, 2011.01.26)

Why Match.com Shouldn’t Have Purchased Dating Site OkCupid (The Atlantic, 2011.02.02)

The Secret Behind Apple’s Calculator Icon Revealed (The Atlantic, 2011.01.21)

What We Know About Murdoch’s iPad-Only Newspaper, The Daily (The Atlantic, 2011.02.01)

Why Groupon Is Worth $6 Billion (The Atlantic, 2010.12.01)

Long Live Blogs: As Readers Flee, Gawker Backtracks on Big Redesign (The Atlantic, 2011.02.08)

Is Gawker to Blame For Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook Stalker? (The Atlantic, 2011.02.08)

0 notes