A collection of my personal impressions of HEMA. Some will be mine own thoughts and some will be the thoughts of others.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

We’re all odd

Emergency Negativity Vent

In seeing a lot of discussions on FB about HEMA that are reminding me exactly why I can't find any joy in it these days. Or at least find little in most of the community.

I mean there's the odd voice of reason, but so many that just make me facepalm.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

IDK man. The structure of the armored sections are so different between the Getty and the PD/Morgan...Fuck the paris...that its hard to even consider them the same pedagogy. Or even system. I mean I get what the Getty is saying. If somebody just rushes at you with that big obvious cover, put a hand on their blade to suppress their stupidity before you give them a bloody hole in the head. and what the PD/morgan are saying is if someone comes with a half sword thrust, smush their hand immediately prior to ringing their bell with the pommel and then the elbow.

I would assume you could get here, the pommel and elbow combo, from a whole bunch of places against either a longened sword thrust or a shortened sword thrust (don’t know what better terms to use out there are but I’m sure you get my drift) from all the poste without too much work... except maybe the PdFM which would only take a slight bit more jiggering to work.

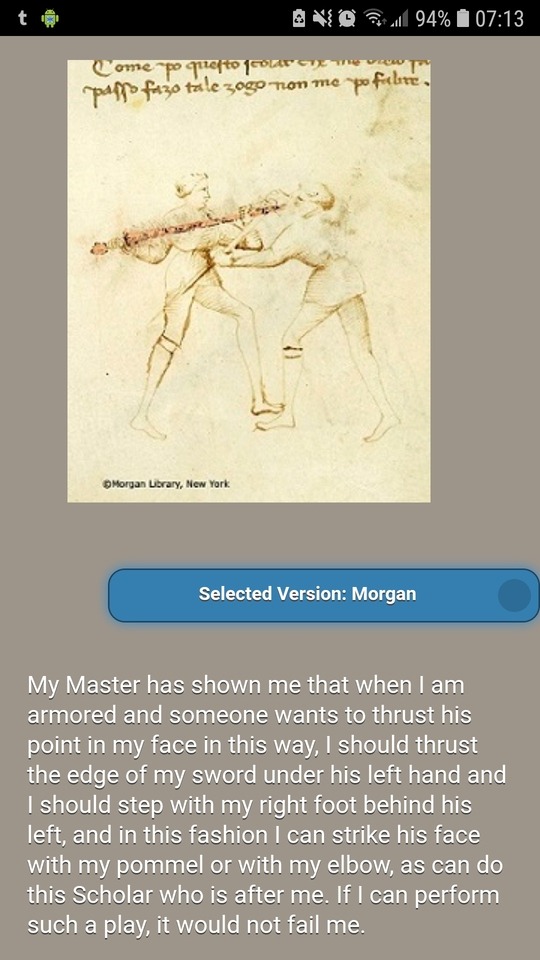

Morgan - Armored Longsword, 1st Master 5th Scholar.

In this bind here, the Scholar has driven their point in a halfsword grip into the opponent’s right hand (1st Master Dagger cover doubled, or the 6th Master dagger 4th Scholar play). From this position, your right hand drops, comes under their left, and you pass your right foot in behind their left, turning their sword out to their right, taking their outer line. Now my favorite part: in the Morgan, Fiore specifically tells us to hit them with the pommel at the termination of this outer line taking, or….

Elbow them in the face.

So your right elbow, being closest to them, does a lateral cut just like your pommel would. Duly noted, and I’ll add that action as canon into my other stuff with the Abrazare.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

@elsegno your first words are “the scholar has driven the point”

Which is not what the Morgan or PD are getting at. (The PD has the wrong person as the scholar according to the text)

Morgan - Armored Longsword, 1st Master 5th Scholar.

In this bind here, the Scholar has driven their point in a halfsword grip into the opponent’s right hand (1st Master Dagger cover doubled, or the 6th Master dagger 4th Scholar play). From this position, your right hand drops, comes under their left, and you pass your right foot in behind their left, turning their sword out to their right, taking their outer line. Now my favorite part: in the Morgan, Fiore specifically tells us to hit them with the pommel at the termination of this outer line taking, or….

Elbow them in the face.

So your right elbow, being closest to them, does a lateral cut just like your pommel would. Duly noted, and I’ll add that action as canon into my other stuff with the Abrazare.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

That sounds fantastic. Thank you. I’ll have to review my notes on terminology so we’re speaking the same language. Nothing like trying to share concepts where you and I are using the same word but with different meanings.

Just a bit of a warning. My impressions and understanding of the IAS methods are mostly limited to largo based upon Sean Hayes YouTube videos and the 2014 family gathering largo workshop videos. Never had any blade to blade (except one time where a CSG member visited our club) with anyone.

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well I asked questions... I think about two years ago when I first joined the IAS and one question was answered with “do it this way because I’ve been doing it this way for a long time and it works” and another ignored for 6 months before I gave up checking the forum on a weekly basis hoping for a response.

If you’re willing/able to help answer questions I’d appreciate it. No bullshit. Not pulling your chain. Legitimately curious to have answers. If you can’t or won’t answer I won’t be offended either so no worries.

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry I should have been more precise at the outset of my argument.

As far as I am capable of rationalizing, specifically applying the quote from the morgan about how much the blades can stay/stand/withstand at the strong middle and weak is as relevant to the rest of the plays of the sword, in and out of armor, and to the axe and spear as well when compared to the application to the 1st Remedy Master of Largo (1RML).

Remember that the in the Morgan Ms, the horsey stuff comes first. And when we get to the first part where it’s sword vs sword which just happens to be on those majestic creatures, Fiore gives us the most basic fundamental lessons on levers. I’m not saying that it’s wrong to apply the lessons of the three crossings from the mounted sword to the sword in any other place, because that would identify me as a complete idiot and I pride myself on being only half stupid.

Using the idea that the amount of pressure on your blade determines what type of possible (possible from the standpoint of maintaining self preservation during the time when blood-letting, praying and sniffing flowers were the recommended methods of treatment for a wide variety of ailments) actions you perform is ludicrous. Relative body position, angulation, angles of blade engagement and line are all critical factors in addition to blade pressure. And relative TEMPO!!!

Dumbing it down to “they’re pushing real hard on my blade so I colpo di vilano that peasant” is insulting to anyone that is forced to listen to it, no matter what level of experience they have.

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

*long slow whistle* that really is impressive movement. I would very much be interested in historical to modern styles comparison as well. Does different equipment fall into that discussion as well? Cuz I noticed the wrappings around what I would call an ?ankle? on the lower part of the horse’s leg? @alchemicalseraph Do those affect the horse’s maneuverability?

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was really hoping that they would chime in specifically for all the reasons they mentioned. But I don’t want to call on somebody without having a direct interaction first.

Cheers and thanks to alchemicalseraph.

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The somebodies happen to be everyone under the influence of the International Armizare Society. And a few others who are in my opinion dabbling with poor logic. But the IAS are pretty committed in their Tomfuckery. I agree with your succinct statements regarding leverage, commitment and movement. It’s not wrong to apply one handed principles to the sword in two hands, but it is wrong to exclusively apply one handed principles to the two handed sword in these modern times as there is no in built self correcting feature any more.

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not having knowledge

Self-Defense Moves You Need to Know by Buzzfeed

There's a quote from an old fencing master from like 1600s that translates roughly into "In these modern times many men are killed or injured for not having weapons or knowledge of their use." I’m pretty certain it’s by Achille Marozzo.

The logical operator 'or' basically means that lacking skills in how one person can attack another with or without weapons is a recipe for disaster. Another half of the situation is if you do have weapons you'll have a false sense of security and will be harmed anyway if you fail to develop the skills. The 'knowledge' here is deep physical skill and technical understanding of violence. Here is the scary part. Empowertopower.org shows that the brains behind this particular venture are a people with a mix of Krav Maga, striking arts and a personal trainer. And you can see pretty clearly that Krav Maga is exclusively on demonstration here. The flawed part about Krav Maga is that it relies on having skill to deliver instant overwhelming violence to your intended target. Not some slightly rusty skills that you can dust off at a quarter of a moment’s notice, or some slightly flaccid body parts that respond sluggishly to the demands placed on them. Krav Maga requires vigilance and dedication. Which I’m an absolute advocate for. But the “EmpowerToPower” team or buzzfeed don’t mention any of that. “Here’s some moves that will save your ass” is right up there with “here’s how to talk to people to improve your life in every way.” One is patently false... no both are patently false but one of them will most likely lead to serious injury if someone relies on them. Being stronger and faster in order to beat an opponent, are the requirements to win a game, and not a legitimate and RELIABLE method to either offend or defend against someone.

Should buzzfeed be considered a trustworthy source for this kind of thing? No. But the +700K shares and +46M views means that this particular version is getting out there. And while the 6K comments are usually derisive on a random sampling, showing that either keyboard warriors and/or people that actually know or care about martial arts, have the correct concerns about this type of message. A paltry 6,000 people compared to 46,000,000 is just too small a portion of people who can actually understand the message. Though I think Master Ken would probably agree with the overall content.

P.S. Gotta love the part at 1:36 where she kicks him in the balls and he falls down holding his head. Good job.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

granite-bones aka rocks for brains

After that cutting post, I have enough new followers to merit the usual announcement: this is a historical European martial arts blog. As such, it recognizes historical fact like the variety of skin tones, religions, and cultures that existed in Europe in the Middle Ages through Early Modern periods, and the contact that those folks and cultures had with the whole world by the 16th century.

I don’t stand for the ahistorical “white European identitarianism” that has become vogue. In my personal life, I’m a pretty radical leftist (which I segregate off onto my personal blog but for these announcements).

I can’t stop folks from following me because a personal review of each blog would be impractical now.

However, for any white supremacists, white nationalists, or Neo-Nazis in the mix: fuck right off. Please understand as well that Nazi-bashing is something I’m both very for and very capable of IRL. I am an unapologetic advocate for violence against the three groups listed above. Feel free to follow, but know in no uncertain terms that I’d beat your ass unconsious and possibly cripple you if I could.

176 notes

·

View notes

Photo

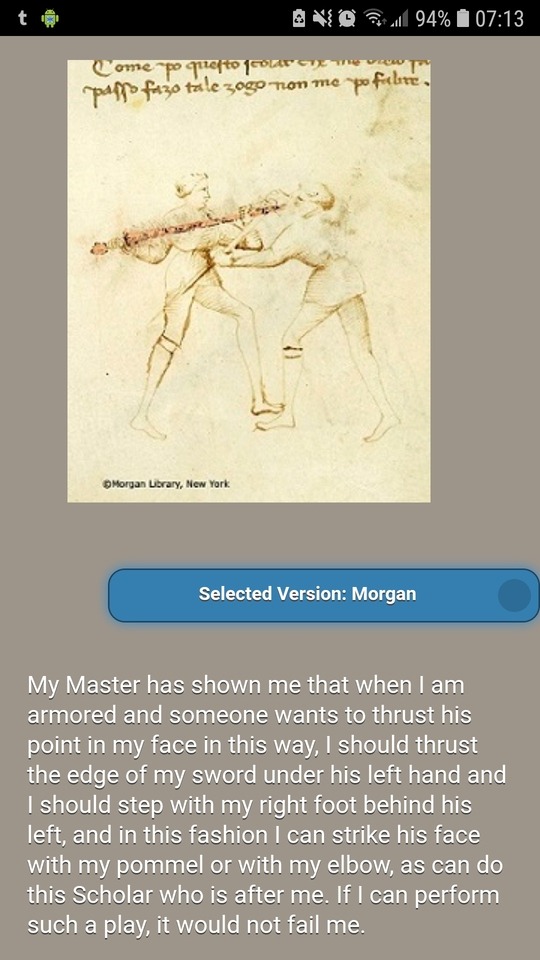

Whups, like i said...I haven’t paid attention to the details of the abrazare plays in quite some time. Again well done flow paths. I can never get the damned things to work on paper.

An internally consistent and complete flowchart of wrestling actions from Fiore. This certainly isn’t the only way to string it all together, but it is a way, from which you can explore and derive other ways.

You gotta know the Posta and how to use them for offensive striking to the most dangerous points (eyes, nose, under the jaw, flanks), and the Largo leg strikes of front kick to groin and side stomp to the quarter knee. Striking/countering via the Posta teaches you to exchange in the straight line. The dagger work teaches you to integrate hammerfists and hooking/suppressing actions into your boxing. After learning wrestling and dagger, the goal is a seamless continuity between them.

Use the Posta to bridge through striking distance to grappling unharmed. If you fail to jamb the collar and elbow, ludic fighters will take a number of holds used in friendly wrestling on instinct, which Fiore’s murder wrestling exploits. Otherwise, if you see a face or elbow, push it. When an arm is stretched against your neck, break it. If you have a hand against their face or throat and are driving them, pick their leg and do 2nd Scholar. And that’s pretty much it!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horseshit

I’ve seen it again. And I’ve decided to write about it this time.

The application of the three crossings on the sword while on horseback from the Morgan version of Il Fior di Battaglia Ms. M.383 to the Largo sections of the manuscripts might be the biggest red herring to interpretation/ interpolation of Fiore’s art.

There are swords and there are people in one section. In the other section there are swords, people and two horses.

So let’s think about how war horses would be involved during a sword fight between their riders. Would they be made to stand placidly in place munching grass and wondering what they did to get themselves into such a stupid situation, would they be moved sideways, around in circles or at full tilt boogie. They might even decide to move of their own accord for one reason or another. Pretty much anything but standing and munching grass is pretty likely.

Well how about those swords? They might be the same sword between the largo and mounted sections I’ll have to admit when looking at the sword disarm plays and evaluating the hilt length necessary to wrap around your opponent’s forearm. But the real difference between using a sword in one hand compared to two hands is how you move the sword. If you think about using a saber for instance, moulinets are pretty much the motion that you expect to see from a cut and thrust weapon. For more of the stabby types of one handed weapons you see the point pretty much held on line the whole time with the hilt moved around to provide protection and opportunity. The reasons for this are due to the interface with the weapon. One hand means that to force the weapon to travel in the reverse direction of an attack will be a great expenditure of effort, which is taught for sport or exercise and not for life and death scenarios, which is why a downward diagonal cut followed by a rising cut on the same line probably wasn’t what you pictured for the saber. Nor would having the point far off line in the case of a rapier or small sword. It would get you nothing but a slower attack if you did manage to cover your opponent’s blade.

So you’ve got comparatively limited dexterity and you’re moving toward each other. What are the things Fiore says you can do sword vs sword. Beat aside and thrust to the face, beat aside and cut to the head, beat aside blade grab and then cut/thrust as before, disarm using your hilt, a counter disarm, a throw by the neck, a counter to that throw, and then the counter to all the previous plays of pommeling the opponent after they have beaten your sword wide (and it’s contra counter). A few things that become immediately apparent to me is that the techniques are basically presented in descending order based upon measure, that beating the blade aside is important for all the plays and that the bind is never broken to strike with the point, blade or pommel.

A rereading of the things Fiore says you can do seems to be based upon if you win line and are far away, if you win line and are a bit closer, if you win line but they start to resist or recover line, if they recover line without immediately attacking (I’m going to say that the need to cover while in range of a potentially fatal wound is not something that Fiore should have had to expressly state and literally draw a picture to explain), if you begin to move past each other, and a counter to that throw and how to counter every time that your sword is beaten aside (you lost line initially) assuming you continue to close.

There is no real blade disengagement unless you’re close enough to basically hug someone. So why the application to largo? Well to the first remedy master of largo’s cut to the other side anyway. Feeling blade pressure and understanding changes in distance are pretty standard pieces of fencing skill to develop. With that being said there is plenty of applicability to the second and third remedy masters of largo. And the masters of stretto. So the masters of swords on horseback do wrap things up nicely regarding blade actions, but the substance of largo, the real gem that goes inside that pretty package is distance management and tempo. Which are really hard to get a horse to coordinate for you.

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

I scanned through it quickly but didn’t see the hip toss. You don’t like their hip throw, or hip throws in general?

A guy from the club sent me a PDF of the old Marine Corps LINE system (the predecessor of MCMAP). It is about 400% better than MCMAP and also straight up Fiore.

Wrestling in the method is basically: Remedy Master of the Abrazare, the Gambarola, and a hip toss (I dont like the hip toss). The knife work is 1st Master Daga cover with follow-ups, 3rd Master Daga cover with follow-ups, and dealing with a low thrust by going to Remedy Master.

There’s also bayonet fighting, sentry neutralization, and weapons of opportunity, which is less relevant.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well if longsword is the area that your talking about I’ve got a few ideas if you’re interested. I’m a Fior-ish-ist, which has a fair bit of variety when it comes to the close play. But the super most fundamental/principle advice to avoid the close play is distance management. Not footwork. Footwork is for dancing around. Distance management is for fencing. Being aware of how close you are (which is a skill that must be developed) to their effective range (determining what your opponent’s range is another skill to develop) and implementing non linear body movement is key. Also not attempting single time counters while standing in place. Very bad idea. Pretty much just write those off to fiction.

I wrote a post that shows what happens-ish when you use different types of distance management techniques against the very typical linear footwork and it also has application against the sloping/step around method that is also commonly taught. https://nerd-plus-jock-equals-hema.tumblr.com/post/129459809577/nuts-and-bolts-of-fiore-largo

If you’re looking for more stretto stuff Guy Windsor’s youtube channel has got a lot of good stuff https://youtu.be/T5aE7a53S0w though in this particular example they’re starting outside of effective range, you can tell cuz they both have to step toward each other, which I’m not a fan of. But it does show a lot of the hand motions necessary to have all kinds of answers to fun stretto problems. Speaking offensively, it is never the offender’s choice to come to stretto. Realistically your opponent can continue to move away forever, which would be boring. But running away is the most commonly advocated defensive tactic. Actual HEMA advice though is use the distance trap. Get your opponent to try to keep a set distance with you by moving forward backward side to side etc until they get comfortable and then BAM change directions to close the distance. Shit thought this would be short. Cheers and have fun.

First swordfighting session

I’d been meaning to try HEMA for quite a while but haven���t really gotten a good chance until the other day and man was it worth it. So much fun but holy hell does it wreck your arm!

If any HEMA folks do happen to see this post is there any advice for beginners on how to deal with people aggressively closing distance (or equally how to do it yourself)?

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some 19th century medievalist must have filled in the blood grooves with gold to make it look cooler

Gold inlaid Viking spear, 9th-11th century.

from Timeline Auctions

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

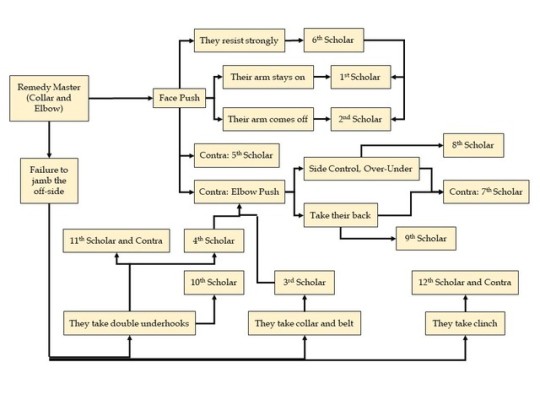

I feel like there needs to be a graphic image of a cannon shooting a boar through an iron door... but that’s probably just me

Looking at combinations of the Abrazare guards, where it’s assumed that the arm straight near shoulder height is Longa, the bent arm chambered in is Boar, and the hand down by the waist or at waist height (extended in the middle in the case of Porta di Ferro Mezzana) is Door.

Treating each arm separately demonstrates that the Abrazare guards constitute a complete upper limb striking method with some implicits. All positions that you would pass through in treating the exchange of thrusts from spear as a boxing method are represented in this interpolation, which makes me more comfortable in viewing my boxing derivation as Applied Armizare (using the principles and the canon positions to do something we’re told to do in the text) instead of Modern Armizare (using principles and applying to a scenario Fiore couldn’t imagine, like using a collapsible baton for example).

13 notes

·

View notes