Representation; Performance; Aesthetics; Genre. These are some of my interests. This blog contains thoughts, ideas, inspiration and conflict - obviously lots of spoilers contained within. Nicholas Graves - 2024 (The writing here has an analytical, critical, reflexive or scholarly purpose; fully attribute all sources used; are made according to Fair Use principles; are non-commercial in nature)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Film Highlight - March 2019

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #March2019, ‘Babylon’, 1980 (DoP - Chris Menges, Dir - Franco Rosso)

0 notes

Text

Film Highlight - January/February 2019

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #January2019 #February2019, ‘La Notte’, 1961 (DoP - Gianni Di Venanzo, Dir - Michelangelo Antonioni)

0 notes

Text

Films of 2018

In this short post I will briefly run through those films which made a lasting impression on me in 2018. For me at least, 2018 was a great year of cinema, one of the most interesting that I can remember in a while - full of challenging, diverse and memorable work.

BURNING

(Director - Chang-dong Lee; Writers - Jung-mi Oh, Chang-dong Lee, Haruki Murakami; Cinematography - Kyung-pyo Hong; Cast - Ah-in Yoo, Steven Yeun, Jong-seo Jun…)

Chang-dong Lee & Jung-mi Oh took a slight, mysterious short story from Haruki Murakami (Barn Burning) and crafted something truly intoxicating. The additional plotting and textures they added work perfectly, building on the essence of Murakami’s story but creating something far more alluring and powerful. Burning is a film that gets under your skin. I could not stop thinking about it after I saw it. I still think about it regularly now.

The three leads are fantastic. Steven Yeun received a lot of praise for his Gatsby inspired enigma, yet Ah-in Yoo straddles the line between ignorance and naivety wonderfully, and Jong-Seo Jun is the beating heart of this film - she is the light and as the third act turns darker, our longing for her is palpable. The soundtrack from Mowg was also one of my favourites of the year, complimenting the sensuality and mystery of the film. Burning was one of many movies this year that tackled the destructive edges of masculinity in a really interesting way.

COCOTE

(Director - Nelson Carlo de Los Santos Arias; Writer - Nelson Carlo de los Santos Arias; Cinematography - Roman Kasseroller; Cast - Vicente Santos, Yuberbi de la Rosa, José Miguel Fernández…)

Cocote is a fascinating film. Narratively simple; it is a familiar tale of vengeance, division and simmering pressure - Alberto returns to his rural hometown to deal with the murder of his father. Yet the aesthetics deployed by Nelson Carlo de Los Santos Arias and his DP Roman Kasseroller are bold, and the resulting effects extraordinary. This film feels alive. It bristles with a kinetic energy and quite literally shifts from scene to scene. Sometimes vibrant colour, then sometimes black and white. Sometimes digital, then sometimes 16mm. Ratios change. Diegetic and non-diegetic sound is used powerfully. 360 pans; now almost a staple of slow, arthouse cinema (see Reygadas, Ceylan and many more) allow us to take in every inch of this world.

Such techniques may be viewed as over-elaborate by some people, Perhaps too busy, too irritating. I thought they were considered and effective here, deliberately creating a work of different textures and flavours. This is the first film from the Dominican Republic I have watched and the different regions, cultures, religions and races were wonderfully realised. This allows the film’s wider themes of colonialism and class inequality to seep through in a potent way.

FIRST REFORMED

(Director - Paul Schrader; Writer - Paul Schrader; Cinematography - Alexander Dynan; Cast - Ethan Hawke, Amanda Seyfried, Cedric Antonio Kyles…)

If I were to choose a film that encapsulated the impending dread that many people felt in 2018, then it would certainly be Paul Schrader’s First Reformed and the sight of Reverend Toller emptying yet another bottle of poison down his gullet. 2018 saw public faith in institutions take a battering, and the greatest crisis of today (climate change) was sneered at, or even worse, wilfully ignored. First Reformed addresses all of these issues directly, but in a perfectly constructed character piece. Ethan Hawke’s performance is incredible. You feel the frustration, the suffering, the anger.

Schrader has absolute control of the material here too and First Reformed feels like a culmination of the ideas and form he has been working on his entire career. The writing, pacing and framing were all spot-on. He breaks his formal rules at exactly the right time, creating moments of beauty as well as power. This is storytelling of the highest order.

HAPPY AS LAZZARO

(Director - Alice Rohrwacher; Writer - Alice Rohrwacher; Cinematohraphy - Hélène Louvart; Cast - Adriano Tardiolo, Agnese Graziani, Luca Chikovani…)

This peculiar film pulls you along on the most unexpected of journeys. While watching, I could not get a handle on where we were heading. It was seemingly one thing, before pivoting to be something entirely different. My advice would be to give yourself over to it. The fact that Rohrwacher based this film on a true story she had read about labour exploitation in central Italy makes it all the more fascinating - and critical. She manages the narrative and tonal changes superbly. What a talent; I can not wait to see what she works on next.

Words of praise should also be given to the lead performance from Adriano Tardiolo. Rohrwacher and her team found him at a public high school. There have been many great performances from non-professional actors recently (Yalitza Aparicio in Roma, Meinhard Neumann in Western, Sasha Lane in American Honey). Tardiolo is truly startling here, conveying innocence and vulnerability with subtle facial gestures. His physicality is superb too, reminding me a little of Chaplin.

LADY BIRD

(Director - Greta Gerwig; Writer - Greta Gerwig; Cinematography - Sam Levy; Cast - Saoirse Ronan, Laurie Metcalf, Tracy Letts…)

Lady Bird is a really smart coming of age film. On the surface this may seem just a light and inconsequential picture, after all, coming of age and high school films are commonplace and they often do nothing more than repeat tired conventions. Yet the way Greta Gerwig deftly uses place and, more specifically, key historical events (9/11, the financial crisis) to subtly comment upon self importance, youthful naivety, and time is very clever. These issues are all there, buried in the background. They are never centre stage and why would they be for a person of this age, it is difficult to be fully aware of the historical significance of events while they are happening, particularly as a teenager.

Also, the dialogue is so rich and identifiable. Plus it is extremely funny. Friends have told me that the mother and daughter relationship felt so truthful to them. It is never sanitised, rather it is presented as messy, painful and touching. Saoirse Ronan and Laurie Metcalf are fantastic in their respective roles. The 90 minutes fly-by and this film has a comfortable, breezy quality to it. It should never be underestimated how difficult it is to make a film with this ambience, lightness and with so much humanity. Billy Wilder, Elaine May and Hal Ashby had the ability to do it; and so does Gerwig.

LEAVE NO TRACE

(Director - Debra Granik; Writers - Debra Granik, Anne Rosellini, Peter Rock; Cinematography - Michael McDonough; Cast - Thomasin Harcourt McKenzie, Ben Foster, Jeff Rifflard…)

It is vital that Debra Granik can raise the funds to make her movies because her voice is sorely needed in U.S. cinema. Leave No Trace is a fantastic example of her work; which focusses on marginalised and often voiceless communities. Her stories reveal themselves slowly and leave a powerful mark on the audience. This is particularly the case with this film, which has a devastating climax. She is an empathetic filmmaker and her characters always feel completely believable. Her work in the documentary form, alongside her extensive research and the relationships she builds with her actors, clearly contribute enormously to this sensibility.

There are two exceptional performances in Leave No Trace - newcomer Thomasin McKenzie and Ben Foster, who I would argue has been one of the most consistently outstanding actors working in the U.S. over the last ten years. Here, he worked with Granik to completely strip back the dialogue of his character to create a painful portrait of a loss soul in the modern United States of America.

LOVELESS

(Director - Andrey Zvyaginstev; Writers - Oleg Negin, Andrey Zvyaginstev; Cinematography - Mikhail Krichman; Cast - Maryana Spivak, Aleksey Rozin, Matvey Novikov…)

Loveless is a superbly constructed film. The plotting and use of time is so well thought through. Oleg Negin and Andrey Zvyaginstev’s script, just like with their previous, equally outstanding film Leviathan is incredible. Loveless is more visually sophisticated. The compositional choices, and the use of blue and white create an appropriately cold atmosphere. The subject matter (a missing child) makes this film a very challenging watch - yet it is never gratuitous.

The themes of the film pierce through with absolute clarity. The systemic nature of some of the social and political problems that exist in Russia are communicated powerfully by Zvyaginstev. In my eyes, he is one of the most important filmmakers working in Europe today and a real master of his craft.

PHANTOM THREAD

(Director - Paul Thomas Anderson; Writer - Paul Thomas Anderson; Cinematography - Vicky Krieps, Daniel Day-Lewis, Lesley Manville…)

Phantom Thread is a difficult film to categorise; part romance, part comedy, part ghost story. It is also, not unlike the designer clothes that its protagonist makes, meticulously constructed. Perhaps it has too much artifice for some people’s taste. I adored it; for all its nods to Hitchcock, its aesthetic beauty and its wicked sense of humour. Johnny Greenwood continues to be making some of the most interesting scores in Hollywood - here his use of lilting, string compositions is gorgeous.

I felt some of the criticism it received in relation to the challenging and toxic masculinity at the heart of film was a little unjust. The film is far more nuanced and complex than it appears. Vicky Krieps is phenomenal in this film, and her character has agency and complexity. After the second and third watch, you begin to see the dynamics and see the central relationship in a completely different light. Phantom Thread is a fascinating and rewarding viewing experience.

YOU WERE NEVER REALLY HERE

(Director - Lynne Ramsay; Writers - Lynne Ramsay, Jonathan Ames; Cinematography - Tom Townend; Cast - Joaquin Phoenix, Dante Pereira-Olson, Larry Canady…)

Lynne Ramsay’s films are so intense. She is such a passionate and emotive filmmaker; her films feel like somebody is grabbing you by the throat and throwing you around. You Were Never Really Here does exactly that and it is such an unrelenting experience. This film had me on the edge of my seat. It is also such a visceral dissection of masculinity and trauma, cleverly using generic tropes many of us are familiar with in new and interesting ways.

Joaquin Phoenix is terrific and a truly terrifying hitman - perfect casting. At eighty nine pulsating minutes, there is not an ounce of fat on this film either. You Were Never Really Here is an absolute fever dream and it truly reminds you how powerful cinema can be.

ZAMA

(Director - Lucrecia Martel; Writers - Antonio Di Benedetto, Lucrecia Martel; Cinematography - Rui Poças; Cast - Daniel Giménez Cacho, Lola Dueñas, Matheus Nachtergaele…)

Lucrecia Martel’s Zama is a towering achievement. Dense, enigmatic and engrossing. Daniel Giménez Cacho’s performance as the exasperated and narcissistic corregidor for the Spanish empire is fantastic. His character goes through such a mental and physical transformation over the course of the film. Far too few films elucidate the horror and futility of colonialism as effectively as Zama. The film is also littered with so many idiosyncratic touches; everything in the frame is so well observed.

Martel always showcases a total control of the medium. Every film that I watch from her leaves me with my jaw wide open - I am in awe of her talent. Every scene tells its own story, you could easily watch them in isolation and still receive so much story and detail from them. Zama is a masterpiece.

#Film2018#Film#Burning#Chang-dong Lee#Cocote#Nelson Carlo de los Santos Arias#First Reformed#Paul Schrader#Happy As Lazzaro#alice rohrwacher#Lady Bird#Greta Gerwig#Leave No Trace#Debra Granik#Loveless#andrey zvyagintsev#Phantom Thread#paul thomas anderson#You Were Never Really Here#Lynne Ramsay#Zama#Lucrecia Martel

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film highlight - December 2018

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #December2018, ‘Burning’, 2018 (DoP - Kyung-pyo Hong, Dir - Chang-dong Lee) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Text

Film highlight - November 2018

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #November2018, 'First Man', 2018 (DoP - Linus Sandgren, Dir - Damien Chazelle) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Text

Film highlight - October 2018

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #October2018, 'Leave No Trace', 2018 (DoP - Michael McDonough, Dir - Debra Granik) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Text

Anatomy of a Scene - First Reformed (2018, Dir. Paul Schrader)

The Magical Mystery Tour

Leading up to this scene we have learnt that Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke) is burdened by a persistent health issue. He is burdened by grief; he has lost a son at war and his marriage has subsequently collapsed. He is burdened by guilt; a soon to be father and environmental activist whom he was counselling has recently taken his own life. He now consoles the widow of this man. He is keeping a journal documenting his thoughts and desperations.

General Observations on Style

First Reformed is part of a group of films that Schrader has made which focus on ‘lonely men in rooms’ (Schrader 2000); these films share similar thematic and stylistic concerns. The stylistic choices are commonly rooted in psychological realism and noir aesthetics. Examples of such in First Reformed include the use of voice-over narration as a through line into the psyche and machinations of the protagonist. Voice-over can often be used as narrative crutch to divulge exposition or convey the message of the film, yet here it is used primarily as a revelatory technique to present private thoughts and inconsistencies. The colour palette designed for the film is stark and muted, featuring dominant shades of black, brown, white, and green. You can also see from the examples of Alexander Dynan’s cinematography below that attention has been directed towards the use of light and shadow. Rev. Toller’s home contains few principal light sources and prominent shadows are cast, which evoke the chiaroscuro used within noir to symbolise hidden turmoil and slippery morality.

Although Schrader does not make films in a transcendental style, he has used nods towards this style within his work before. First Reformed shares more stylistic similarities with this style than any of his previous films, and actually seems designed as an exploration of transcendental ideas confronted by psychological realism. As such, the decision has been taken to make the film in the more austere academy ratio (1.371 : 1), calling to mind great proponents of transcendental style like Robert Bresson and Yasujirô Ozu. The tighter composition can also inform our understanding of Rev. Toller’s psychology, perhaps suggesting claustrophobia and a world closing in on him. The duration of each shot is longer than those found in your typical Schrader film. In addition, First Reformed is covered mainly through static shots and features no over-the-shoulder shots - techniques Schrader identified as being key tools within transcendental cinema. He notes that the purpose of these techniques is to encourage the viewer to lean into the film and consider the material, arguing that they are “not to make you emote, but to make you understand…designed to gradually replace empathy with awareness” (Schrader 2018). Another technique that encourages the audience to lean in and engage with the material is the lack of non-diegetic sound, which is typically used for illustrative purposes. First Reformed features no non-diegetic sound until the 65th minute mark, when Brian Williams’ score finally begins to seep into the film. This happens almost mid-way through the film and immediately after Rev. Toller begins to search through troubling climate change material collated by the deceased activist he was counselling. The inclusion of the score at this point seems to signify to the audience that Rev. Toller’s psychological turmoil is turning darker, perhaps irrecoverably so.

Scene Opens

Rev. Toller’s voice-over leads the audience into The Magical Mystery Tour scene, remarking that he has ‘removed the previous pages [from his journal]. They were written under delirium, but [he is] determined to continue’. Visually the scene opens on a fragmented perspective of Rev. Toller as his dark figure is glimpsed writing through a reflection in a mirror. Rev. Toller’s voiceover remarks that ‘it’s hard to struggle against torpor. [He] must set pen to paper’ and we cut to an overhead shot that illustrates pages have been ripped from the journal. The juxtaposition of the narration, which suggests a newfound clarity of thought, and the image, a partially viewed Rev. Toller, is telling here - the film has alerted us to the unreliability of its narrator, which is also beginning to manifest itself visually.

The camera moves to a static wide shot which is composed fascinatingly. Rev. Toller is viewed centre right of the frame in a far room in the distance, while centre left framed and foregrounded in the room closest to the camera sits a solitary chair.

The rooms are particularly sparse so the eye becomes drawn to this chair which is somewhat improbably positioned. It is difficult to imagine why somebody would take this position in an empty room. Rev. Toller is now heavily drinking and pours a glass of whisky before being surprised by a knock at the door. Hawke’s performance emotes surprise as he peers through the open door towards the main door (which lays offscreen). He finishes the drink and walks to answer the door offscreen. We hear him welcome Mary (the widow of the deceased activist) who anxiously enters the room confessing that she does not feel okay.

Of course, it is Mary who sits on the peculiarly placed chair, almost as if it had been placed there especially for this moment. Perhaps in the drunken, hazy mind of Rev. Toller it had been. Hawke’s performance is again very interesting here as he takes her coat, looks off screen, and then looks around briefly, like he too is disbelieving Mary’s presence here.

We then have a simple series of medium-close ups as Rev. Toller and Mary converse. Perhaps most interesting to note during this exchange is the way that point of view shifts as the conversation progresses. As Rev. Toller is standing and Mary is sitting, the camera’s point of view has us looking downwards to a vulnerable Mary and upwards towards Rev. Tolller. Yet as Mary confesses that her negative thoughts just keep ‘repeating and repeating’, words appropriate for Rev. Toller given his current state of mind, he kneels down to show attention and thus the point of view shifts dramatically. We now look upwards towards a more commanding Mary and downwards towards Rev. Toller. Mary explains the The Magical Mystery Tour, a playful act that she used to do with her late husband:

‘It sounds silly, but we would share a joint and lay on top of each other fully clothed. Then we would try to get as much body contact as possible. We would have our hands out and we would look straight into each others eyes and move them in unison, right, left, right, left…and then we would breathe in rhythm.’

The framing of Rev. Toller here is revealing, particularly alongside Hawke’s performance. He appears completely transfixed by her story and gazes upwards, admiringly; the downwards point of view makes him appear small within the frame, childlike in his infatuation. He is beguiled by this story of connection and intimacy. The description of The Magical Mystery Tour act is slightly unusual, yet more surreal is that Rev. Toller goes on to ask Mary if she would like to do this with him now, to which she replies yes.

After an establishing wide shot to show Rev. Toller and Mary taking their position, we cut to an overhead shot that is particularly effective as it shows Mary’s body completely consuming the image of Rev. Toller as she lies on top of him - perhaps mirroring the idea that her presence in his thoughts is becoming all consuming too.

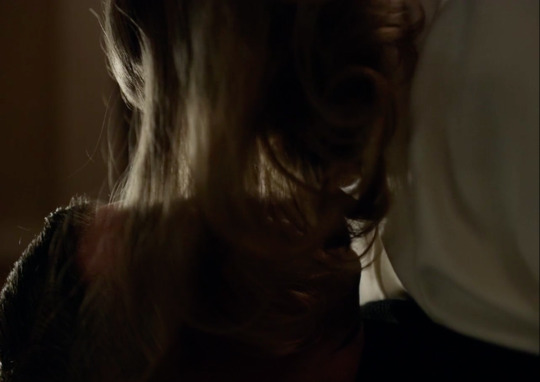

The edit cuts to an extreme close-up of their faces. It is here that the decision to adorn Mary with a white shawl is interesting, as within this frame it looks strikingly similar to the liturgical vestment that Rev. Toller wears when delivering sermons - enhancing a sense of connection between them. The extremity of the close up allows us to pay attention to the performances of the actors. Amanda Seyfried playing Mary moves slowly up and down as she breathes deeply, while Hawke emotes complete stillness, like he has stopped breathing altogether. There is a sensual control and dominance to Seyfried’s performance in this scene, which is in contrast to Hawke’s presentation of Rev. Toller, which is reticent and nervous. It is Mary who initiates the opening of their palms so that they can connect more fully. The tension established reaches its crescendo when Mary’s hair falls across the face of Rev. Toller. Again, this consumes his image within the frame which could lead to the viewer sensing that Rev. Toller has been overwhelmed, or that he has given himself over to her fully.

Visually, transcendence is then made literal by the film. This also confirms more clearly to the viewer that this scene reflects the psychology of Rev. Toller more than anything based in reality. Dynan’s ethereal score begins, adding to the sense of the fantastical, and both the bodies float up from the ground. The film is now breaking a number of its formal rules and this continues as the static shot is broken and the camera pans around the bodies as if it were floating too. The room fades to stars around them.

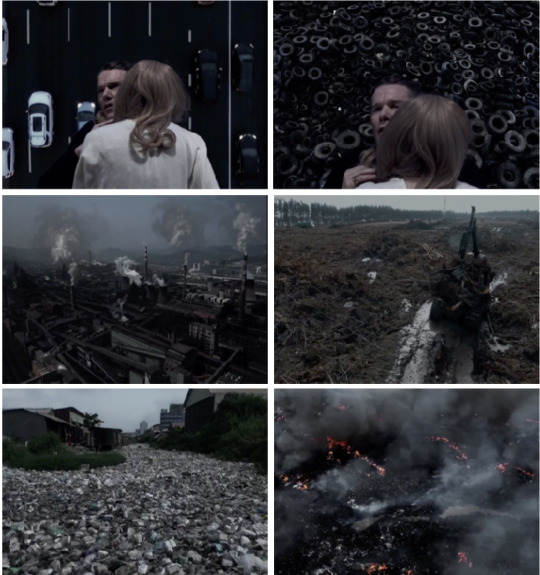

A montage of images are used as the background to their [his] journey, and both characters appear like they are flying through the scene. It is noteworthy that this spiritual and emotional connection to Mary is visualised alongside wondrous images of nature; mountains; green forests; oceans; coral reefs. One might interpret that the joy of connecting with another individual has brought to Rev. Toller’s mind other great joys that God has bestowed on us through his creation.

However, Rev. Toller is undergoing an extreme crisis of faith and this also begins to reflect itself psychologically through the images in the montage. The camera pans upwards towards an overhead shot once again, and Rev. Toller´s image is no longer fully enveloped by Mary; instead he is anxiously peering over her shoulder as his worries begin to crash the fantasy. The score does a lot of the illustrative work here as it shifts tone from ethereal to a more industrial, drone style. The images we now see are heavy traffic followed by thousands of tyres on a scrapheap. The camera pans further upwards and the characters exit the frame completely; an intimate moment now lost. All that remains in the frame, and in the mind of Rev. Toller, are the following images: industrial factories bellowing smoke into the atmosphere; deforestation; an ocean of garbage covering streets; wild fires raging; a rusting shipping vessel littering the ocean.

The tension within this crucial scene reflects the tension at the heart of First Reformed, and it is clear to see which thoughts are beginning to dominate our protagonists mind, in the most destructive of ways.

A slow fade to black.

Bibliography

Schrader, M. B. a. P. (2000). "Affliction and Forgiveness: An Interview with Paul Schrader." Film Quarterly 54(1): 2-9.

Schrader, P. (2018). Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, University of California Press.

Note: This essay utilises still frames from Paul Schrader's FIRST REFORMED (2017) under the guidelines of fair use for analytical and educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

Film highlights - September 2018

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #September2018, Network, 1976 (DoP - Owen Roizman, Dir - Sidney Lumet) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Text

Searching for a Little Grace, Again

Although Paul Schrader doesn’t make transcendental films, he does use slight gestures towards transcendental style within his work to elucidate the psychology of his characters, evoke the fantastical and suggest a bleak reality - his 1992 film ‘Light Sleeper’ demonstrates this.

Paul Schrader’s Light Sleeper, his ninth feature as director, feels familiar. The film is set amidst the trash, scum and degenerates of New York city at night, and we follow loner John LeTour, who is a drug dealer longing for purpose and redemption. We have followed similar incarnations of LeTour before; he was called Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver, 1976) and then Julian Kaye (American Gigolo, 1980). LeTour then transformed into Carter Page III (The Walker, 2007) and Reverend Toller (First Reformed, 2017). Upon writing The Walker Schrader noted he was envisioning a ‘tetralogy’ of films which followed a lonely man in his room, they ‘want a life, but can’t figure out how to get one. He goes from anger to narcissism to anxiety to someone deeply superficial’ (Schrader 2000).

Overtly connecting a particular body of your work implies that common preoccupations may be found, and the concerns of these characters could ostensibly be read as reflecting some of Schrader’s concerns at different times over the years. Yet each of these films contains stylistic similarities which, to me at least, are just as revealing as characterisation - psychological realism, with a very brief nod towards transcendental style. It is a stylistic coupling that helps to create a focus and coherence that has spanned forty one years. In doing so, the approach also presents a bleak outlook, one that is reinforced and made bleaker by each passing film.

Schrader’s relationship to transcendental style in film is well known; he literally wrote the book on it. He summarises one of the purposes of transcendental style as to ‘gradually replace empathy with awareness’ (Schrader 2018). This awareness is achieved through three stages: the creation of the everyday world as cold and lacking meaning (established through excessively long shots; static framing; lack of non-diegetic sound; stylistic devices often associated with slow cinema). This is followed by disparity (‘a spontaneous expression of the holy’) that culminates in some kind of decisive action which finally leads to stasis, where we return to the hard everyday world but now with the awareness that the transcendent/holy ‘is beneath every realistic surface’ (Schrader 2018). Schrader does not make transcendental films, and certainly not in the mode of those he wrote about like Yasujiro Ozu or Robert Bresson. However, his most recent feature First Reformed, particularly within the first hour, does share more similarities with this style of filmmaking than anything he has made before. Alongside the literal subject matter, a reverend experiencing a crisis of faith, it can be read as a cumulative exploration of purpose and faith, and a deliberate pairing of styles - within this film psychological realism and the transcendent seem intertwined. This is drastically different from Schrader’s previous lonely man films, which contain only fleeting yet nevertheless interesting moments of transcendental style.

Returning to Light Sleeper, this style shows itself after the climactic shoot-out. After killing three thugs, a critically wounded LeTour sits centre framed on the edge of the bed. Willem Defoe’s performance strangely emotes no pain or anguish as one would expect, instead he projects stillness and absence. As LeTour’s eyes roll back, his stiff body slowly descends onto the bed while in unison, the camera ascends above him. The audience looks down at his body lying in state; has his spirit ascended? Following a fade to black, Schrader presents us with a coda where an alive LeTour is visited in prison by his boss, Ann. He has come to the realisation that he can now look forward in life and confesses that he hopes to begin a romantic relationship with her once he leaves prison. Schrader then recreates a similar shot that he used at the end of American Gigolo, which in turn was lifted from Bresson’s Pickpocket, thus deliberately evoking transcendental style. Ann takes LeTour’s hand; then the film cuts to a reverse shot that shifts to half, perhaps even quarter speed while slowly zooming towards a subservient LeTour who gently kisses the hand - the close up is unnaturally held for thirty seconds before freezing and allowing the credits to run. Is this coda fantastical? The peculiar, fleeting nature of this moment jars with the conventional genre narrative from which the film operates. After all, It is genre convention and psychological realism that dominates the style of Light Sleeper.

All these lonely man films fit most recognisably within the crime drama and thriller genres, and are filtered through Schrader’s love of film noir. Violence, sex, prostitution, drugs, corruption, and suicide all feature prominently. Committing his thoughts to the article Notes on Film Noir in 1972, Schrader observed some key features of the genre. Romantic narration, realistic exteriors, the majority of scenes shot for night, and a more honest and harsh view of the world. ‘The how is always more important than the what’ and there is the ‘over-riding noir theme: a passion for the past and present, but also a fear of the future’ (Schrader 1986). These attributes feature unmistakably in Schrader’s own work.

Light Sleeper is narrated by LeTour and the majority of the action takes place at night as he is chauffeured from stash house to clients. In a somewhat overwrought touch, the film is set during a garbage strike so as the film progresses, trash and filth pile-up on the streets. Coincidences are woven into the plotting of the film and the character LeTour is obsessed with his luck and visits a psychic healer multiple times seeking reassurances about his future. The worlds painted by Light Sleeper and it’s kin are bleak and unforgiving. The lonely man films focus intently on the psychology of their central character, and the characters share similar problems. Each protagonist is presented as isolated, both socially and emotionally. They are despairing or tired at the sin that surrounds them and are seeking ways to act, to alter their fate and to find catharsis. For the great directors series in senses of cinema, John R. Hamilton identifies a causal link between the views of these characters and some of Schrader’s own outlooks, proclaiming ‘Schrader is a modernist. He believes in good versus evil. Schrader is an existentialist. He believes that this life matters, and that we are working towards a telos, an end’ (Hamilton 2010). The predominate style of these lonely man films is born from genre conventions and psychological realism; it is this style that brings to life the seedy, marginalised worlds in vivid detail and forms characters that are authentically tragic. It is within this context that brief instances of transcendental style occasionally crash through, and jolt the film sideways due to the fact they are at odds with the predominate style. Some may read these strange moments as symbolising hope, and as a type of salvation through grace for these tortured men.

Writing in the Journal of Religion & Film, Jason Abrosiano wrote that ‘LeTour’s suffering ceased being suffering the moment it found meaning’ (Ambrosiano 1998) - within Light sleeper, as with all of the other lonely man films, this occurs when the protagonist decides to make a stand and take some kind of action. Prior to this they have been distant and resistant to meaningful decisions, merely scorning the world from the margins. LeTour’s decisive action is phoning the police to inform on Tis, a drug client whose home was the location of a suspicious suicide the night before. This action leads LeTour to the climactic shoot out where he is critically wounded. The ending is similar to that of Schrader’s first lonely man film, and his second screenplay, Taxi Driver.

In Taxi Driver Travis Bickle also takes decisive action which culminates in a shoot out that leads to him sitting in a pool of his own blood. Much has been written about that film’s peculiar ending, which begins when the camera moves across the room, looking downwards from the roof, god-like. ‘While the surfaces of urban realism remain, events become increasingly more unlikely […] improbable coincidences […] Travis’ extraordinary healing, push the ending from miraculous to the point of fantasy’ (Blake 2017). Schrader plots within his narratives coincidences and inconsistencies, and often asks the viewer to question the reliability of his narrators. The implication being that a number of key moments within the narrative (perhaps even the climactic set pieces) could well be taking place in the protagonist’s head. When brief moments of transcendental style then arrive, I feel the fantastical is further implied. Never have I left a Schrader film believing in the redemption or the catharsis. With each passing lonely man film this feeling is reinforced further as those common preoccupations and insecurities resurface once more, but now in a slightly different guise. Psychological realism always predominates the style and any hints toward transcendental style evoke the fantastical. Perhaps the bleak nihilism beneath Light Sleeper and all of these films is the suggestion that any higher meaning, greater purpose or catharsis is also fantastical. Of course, one may read that as honest realism rather than bleak nihilism, depending on your particular viewpoint. Who knows if Schrader, now 72, will add further films in this vein to his body of work. Schrader had suggested that he was done making movies that featured suicidal glory, but he recalls a response from a friend who was addressing this claim: ‘You know those suicidal feelings that went away? Don’t worry; they’ll be back’ (Schrader 2000).

1) I have included Schrader’s most recent film First Reformed alongside his ‘tetralogy’ as it shares kinship thematically and stylistically. Schrader has noted this relationship in a number of press interviews for the film.

Bibliography

Ambrosiano, J. (1998). ""The Ties That Bind and Bless the Soul": Grace and Noir in Schrader's Light Sleeper." Journal of Religion & Film 2(2).

Blake, R. A. (2017). "Inside Bickle's Brain: Scorsese, Schrader, and Wolfe on Psychological Realism." Journal of Popular Film and Television 45(3): 139-151.

Hamilton, J. R. (2010). "Paul Schrader." Great Directors, from http://sensesofcinema.com/2010/great-directors/paul-schrader/.

Schrader, M. B. a. P. (2000). "Affliction and Forgiveness: An Interview with Paul Schrader." Film Quarterly 54(1): 2-9.

Schrader, P. (1986). Notes on Film Noir, Film Genre Reader 2.

Schrader, P. (2018). Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, University of California Press.

#Paul Schrader#United States#Hollywood#Psychological Realism#Transcendental Style#Light Sleeper#First Reformed#American Gigolo#The Walker#Taxi Driver#Crime#Drama#Thriller#Film Noir

0 notes

Photo

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #August2018, 'First Reformed', 2018 (DoP - Alexander Dynan, Dir - Paul Schrader) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Photo

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #July2018, 'Certain Women', 2016 (DoP - Christopher Blauvelt, Dir - Kelly Reichardt) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Photo

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #June2018, 'Body Double', 1984 (DoP - Stephen H. Burum, Dir - Brian De Palma) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes

Photo

An image from a new film (well, new to me at least), which has made an impression on me this month: #March2018, 'The Last Picture Show', 1971 (DoP - Robert Surtees, Dir - Peter Bogdanovich) #Film #Cinematography #Art

0 notes