Text

“Mija, si yo tuviera la oportunidad...yo lo hiciera”

As the Mexican-American daughter of two Mexican immigrants, I grew up constantly being told “Mija, si yo tuviera la oportunidad de terminar la escuela o darte todo lo que querías, yo lo hiciera”. It hurt to hear that because they have done so much already for me. More than I could ever repay them. It hurt knowing that my parents were forced to migrate to the United States in order to help out their families back home, living in poverty, sacrificing their happiness. They were around my current age, 20, when they first came to the U.S and started working. I'm in my 20’s at college. My father worked on a ranch in Texas and then moved to New York. My mom came directly to her sister in New York and worked at a factory in Sunset Park. They met at a club one night, fell in love and my mom had my oldest sister in 1992. My second eldest sister was born 3 years later, and I was born 9 years after that at 2 am on June 28th 2001. Growing up both my sisters were academically successful. I, on the other hand, was the complete opposite. Both my parents, full-time working class citizens and parents, stressed to me how important education was. “Tu educación es la cosa más importante en tu vida”. “Quiero que te graduas, porque sin ese papel diciendo que te graduaste, vas a tener un tiempo difícil encontrando trabajo”. My father gave up his dream of becoming a pilot to become a construction worker. working 16+ hours daily, 5 nights a week. He’s gotten into multiple work accidents and has lost a finger on the job. My mother also gave up her dream of becoming a flight attendant to become a full-time mom and housekeeper, working 40+ hours a week. Both worked tirelessly to provide my sisters and I, and family back home in Mexico, with the means to survive and succeed. As I’ve grown up, I’ve come to appreciate the labor of my parents. The labor and struggle to survive, passed down through family generations, to keep me and my sisters alive. The labor that made me realize how important school is for me, as a proud first-generation daughter of Mexican immigrant parents. School, despite being an institution created to produce working class citizens, has been ingrained in the minds of my sisters and I, as the ticket to success and wealth. While I hate school at times and wish that I could drop out, I remind myself of the sacrifices and hardships my parents and ancestors made to get me where I am today. Not many students of color, especially of immigrant or low-income backgrounds, have the privilege or option to drop out because their families financially depend on what their kids could become. For many friends of mine of immigrant and low-income background, school is the only way out of poverty. However, others, like my parents, sacrifice their education because going to college costs too much. It angers me when I hear that “If you work hard enough, you can do anything!” because people then deny the realities that people of color, of immigrant and of low-income backgrounds, experience. They underestimate the power and legacy of institutionalized racism and classism. Because if that was true and people truly were able to obtain anything through hard work, my parents, along with other people of colors’ parents would have the world.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

science says the universe is expanding. never let anyone tell you there is no room for you here. there is. there is. you belong here.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Boy will be Boys”

TW: Mention of sexual, verbal and physical assault, rape, domestic abuse, child abuse, violence against women and children, femicide.

“If a boy is mean to you, it's because he likes you”. I think of this phrase every single time a man has sexually harassed or assaulted me, flabbergasted at the normalization of violence against women. I think of the white man three years ago who caressed my thigh on the bus ride home and told me he wanted to “rape me and show me the night of my life”. Did he like me? I think of the boyfriend I had who constantly belittled me, physically and verbally assaulted me and made me want to die. I think of all the countless stories women have told, and the ones never told because they never had the space or support to share. I think of the women and children sex trafficked everyday and the countless videos of non-consensual violent pornography displayed to the public, both crimes and profitable for those uploading it. I think about how one of those videos could have been me when I found out my childhood babysitter was a pedophile who abused me and other kids. Or when I found out one of my high school teachers was arrested for child pornography and making minors do sexual things for his pleasure. I think of the never- ending stories of violence our women endure, profitable within our society. Like the murder of Marisela Escobedo Ortiz and her daughter Rubi Marisol Fraire Escobedo. Her daughter was killed for wanting to leave her murderer, after finding out he wasn’t who she fell in love with. And just like her daughter, after protesting and raising awareness relentlessly of the murder and the Mexican government’s compliance in it, Marisela was silenced and killed.

Women are constantly having to fight for their right to live and be treated as equals. And when we do, we are either criticized, assaulted, raped, silenced or killed. It’s difficult to live within a world that thrives off of breaking you and normalizing your pain, Your oppression becomes part of their daily routine. There's a poet called Olivia Gatwood and her poem “If A Girl Screams In The Middle Of The Night'' (2019), describing the violent endings many women encounter. She begins her poem by stating in caps the truth that society will hide from many women in order to control and oppress them;

“IF A GIRL SCREAMS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT

and no one is there to hear it

here’s what happens. i’ll tell you.” (Gatwood, 5, 2019)

Gatwood illustrates the violent murders of women and the suffering endured.

“if she is in the woods, it shoots

from the cannon of her throat

& smacks itself against a branch,

whips around it like a tetherball.” (Gatwood, 5, 2019)

The disappearance of women.

“if she is facedown in the moss,

it seeps into the forest floor’s pores,

& every time a hiker passes through,

the days beyond her unravel..” (Gatwood, 5, 2019)

Mistreatment of women experiencing trauma and violence.

“if the girl is in the city,

the scream get lodged

in the cubby of a neighbor’s ear

prevents him from sleeping at night

& so naturally, he sells it to a second hand store

he takes it to the buying counter

in a jewelry box & says,

i don't know who this belonged to

but i don't want it anymore.

& though the pierced & dyed employee

is reluctant to take it, she sees the purple

bags rotting figs under the neighbor’s eyes

so she offers store credit.” (Gatwood, 5, 2019)

Pleasure derived from perpetrating violence on women.

“& so not to startle customers,

a small label will be placed on the box

that says A SCREAM & each time a person cracks

it open the the girl’s rattling tongue will shake loose

into the store. this happens for months but no one

wants to buy it, to take care of it. everyone wants to hear it once to feel something & then go back

to their quiet homes, so the store throws it

in a dumpster out back, where the garbage

truck picks it up & smashes it beneath

its hydraulic fists. the scream will get buried

in a landfill somewhere in new jersey

& later the landfill will be coated in a grass,

where a wandering child will see a hill,

will throw her body against it

& shriek the whole way down” (Gatwood, 5-6, 2019)

Femicides occurring in Juárez Mexico are proof of institutionalized violence against women. Since the mid-1990s, “international media began to fixate on hundreds of gruesome killings of women: mostly young women of modest means. News stories reported on bodies found en masse in the Chihuahuan desert, at times describing evidence of trauma and torture in lurid and objectifying detail. No one knows exactly how many women have been killed or kidnapped in Juárez, but gender-based killings continue”. It wasn't until 2019 when the Mexican government “registered 1,006 victims of gender-based homicide across the country, with 31 of those in Chihuahua state, where Juárez is located”. According to Mexico's attorney general, that is a “137% increase over five years”, including only women who have been found”. Countless amounts of “crimes go undiscovered, unsolved and unpunished, enough that homicide on the basis of gender has generated its own official classification in Mexico and in much of Latin America: femicide”. Femicide encapsulates not only the “killing of victims who happen to be female” but also “the systematic violation of human rights. Whether through domestic violence or sexual assault, the victims of femicide are women who were killed because they are women” and it should be recognized as such (Chin & Schultz, 2020).

Women’s stories are constantly disposed of, silenced and erased from the world because it exposes the structural violence we experience and how embedded it is within our society. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, “1 in 5 women” are “victims of rape or attempted rape during their lifetime”,”1 in 5 women” have “experienced contact sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime”, “19.1 million women” have been stalked, and “1 in 2 female murder victims” are “ killed by intimate partners” (NCADV, 2, 2020). The list goes on and on. And that again, only counts for REPORTED acts of violence. For an institutional and global issue, we must create an institutional and globally effective solution to end the normalization of gendered and sexual violence against women.

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence:

If you are in immediate danger, call 9-1-1.

For anonymous, confidential help, 24/7, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE) or 1-800-787-3224 (TTY).

National Child Abuse Coalition:

If you know someone who is in trouble or needs assistance, call the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453).

Works Cited:

Chin, Corinne, and Erika Schultz. “Disappearing Daughters.” The Seattle Times, 8 March 2020, https://projects.seattletimes.com/2020/femicide-juarez-mexico-border/.

Gatwood, Olivia. “If You Hear A Girl Scream In the Woods.” The Life of the Party, 1 ed., Dial Press Trade, 2019, pp. 5-6.

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (2020). Domestic violence. Retrieved from https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/domestic_violence-2020080709350855.pdf?1596811079991

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Although men are more likely than women to be murdered, women are more likely than men to be murdered by a member of the other sex and by a spouse. MacKinnon (1987) reports that “four out of five murdered women are killed by men; between one third and one half [of murdered women] are married to their murderers. When you add in boyfriends and former spouses, the figures rise.” Dobash and Dobash (1977/78) reported finding that more than 40 percent of women who are murdered are murdered by their husbands. By comparison, only 10 percent of male murder victims are killed by their wives. Walter Gove (1973) found that “for women the shift from being single to being married increases the likelihood of being murdered, while for men the shift decreases their chances.” Gove obtained similar findings for single as compared to married women as regards “accidental deaths.” It is, of course, likely that many accidental deaths were in fact murders. Such statistics served as the impetus for Blinder’s (1985) remark, “In America, the bedroom is second only to the highway as the scene of slaughter.”

Loving to Survive by Dee L.R. Graham (via fall-and-shadows)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

If they touch my daughter, I burn everything

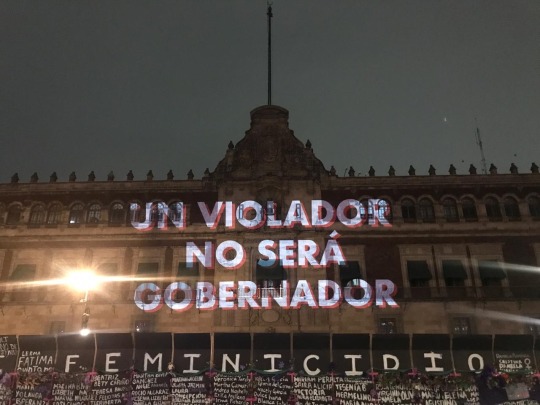

[Mexico] February 2021 / March 2021 #8M2021

- @Emily_Lykos

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

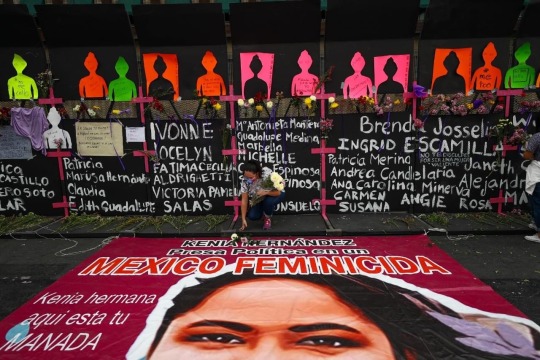

The Mexican government cares more about buildings and monuments than the 10 women and little girls killed EVERY DAY in the country.

They surrounded the “National Palace” with metal walls to prevent “vandalism” from paint, glitter and banners like last year.

They protect and defend the walls from paint better than they protect us from being kidnapped, raped, killed or letting our abusers roam free.

They placed walls to protect their buildings from the upcoming March 8th Woman’s Day march, but we still found a way to protest and make our voices known.

“Femicide Victims” written in big letters with paint across the metal walls, and underneath the names of the women and girls who aren’t with us anymore.

( Picture by: https://www.instagram.com/p/CMG_II9nrwT/?igshid=u2hb64t5odl3 )

As the day passed phrases were projected on the front of Palacio Nacional like:

“Femicidal Mexico”

“A rapist will not be governor.”

(Pictures by: https://twitter.com/tania_tagle/status/1368743529623810049?s=21 )

And soon enough more and more women joined in and gathered at the Zocalo to place, signs, pictures, flowers and more stuff to remember the ones that aren’t here with us anymore and to take over something that was meant to shut us out at the beginning.

(Picture by: https://twitter.com/lilifavela_/status/1368737193527816196?s=21 )

(Pictures by: https://www.instagram.com/p/CMJL0OWD_yi/?igshid=1u5bdgic9vww4 )

instagram

“The wall that got turned into a memorial”

We are tired, we are angry, we are worried and scared. We are often demonized by the mexican media and mocked by many other mexicans for protesting in different ways, from peaceful to non-peaceful. But we will keep fighting and raising our voices!

For our sisters

For our mothers

For our aunts

For our daughters

For our grandmothers

For everyone who isn’t here anymore.

This is just a little bit of everything that’s happening in Mexico, I encourage you to share and search more about this subject. (https://abcnews.go.com/International/380-women-killed-mexico-year-activists-cultural-change/story?id=69258389)

Help us raise our voices, help us be heard!

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rape New York by Jana Leo

Jana Leo’s memoir Rape New York chronicles her traumatic experiences as a survivor, revealing the myriad of neglected realities of survivors unable to voice their truth and the intertwined structural acts of violence, contributing to the likelihood of one out of ten women, being raped.

Towards the end of the novel, Leo reveals what life has been like as a survivor of rape. She states that instead of “blaming him”, she “calmly analyzed the damage done by his abuse”. Her “relationships suffered and eventually ended”. She felt like a “refugee without a home” and had lost “self-control and hope”. “Constantly sad” and “lacking enthusiasm”, Leo ended up isolating herself, changing her perception of life. She began to “live in fear” (Leo, 109). Her world shifted the minute he decided to feel the need to take control and invade her home and body. She states “his presence altered my life to such an extent that I too became a stranger, strange to myself and strange to others” (Leo, 4). The author details the feelings of dissociation that survivors have, which is a coping mechanism for people suffering from PTSD. Weeks after the rape, as Leo was picking up mail from her old apartment, she thought she saw her “assailant in the grocery store” (Leo, 48) and Detective M brushed it off, as it being someone’s normal response after going through something traumatic. But in Leo’s gut and body, she knew that it was him. After seeing him, Leo began to question the whereabouts of the rapist and his knowledge of her location.“Would he return?... Where does rape happen and where doesn’t it happen?”. This led to Leo revealing the “myths associated with rape and the home” such as “the image of the house as a safe place, offering comfort and suppressing the threat of rape from the mind” (Leo, 49). However, the reality is that “one in four female rape victims is rapes in or around her own residence” (Leo,50). And it is because “rape is domestic” due to the failed efforts of securing “buildings, tenants and the home”, exposing the tenants to violence (Leo,51).

Referencing New York within the title, Leo already emphasizes the importance of her incident’s location (being her apartment in Harlem) and its ties to race, class, and gender. Leo states that aside from the “bigoted images of white women being raped by black men, rape statistics show that perpetrators tend to victimize members of their own race. The premise that a white woman is more likely to be raped in Harlem, a black neighborhood, is a stereotype. But the premise that any woman is more likely to be raped in Harlem, a poor neighborhood, is based on facts” (Leo, 94). The rapist, later on in the memoir, is revealed to have also raped another woman, a “Mexican immigrant working as part of the housekeeping staff in a Hotel in Harlem”. The author observed that “besides being assaulted by the same man and despite our differences, we had something in common: we were both poor, which is why we were both in Harlem. She was poor and working class. I was poor but partly, by choice…interested me” (Leo,105). Leo states this in order to address crime, one must address poverty because of its connection to who it affects, how it affects them and others and where it takes place. “Addressing poverty means providing education and work and good wages and benefits” and combats the notion of poor individuals as “less valuable”. This perception of low-income individuals has affected Leo and the other woman raped by William, because “perhaps a rape in Harlem, in the mind of a rapist, is seen as more ‘casual’ than a rape committed on the Upper East Side, since residents of Harlem are more used to being victimized, and a violent act is less likely to be reported. Perhaps the police treat rape more lightly in a poor area than in an affluent neighborhood….To rape a rich person is certainly more risky to the perpetrator, since not only is the act more likely to be reported, it will probably be investigated more thoroughly” (Leo, 93). According to the (2007) Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape, people “in poverty are often either ignored or penalized by the larger society. Therefore, poverty often serves to silence and discredit victims/ survivors, especially when it is compounded by other forms of oppression and isolation” (pg.7)

0 notes

Text

decolonizing

I hated school growing up. I didn’t understand at first why I dreaded going every day to learn because I genuinely loved learning. I just really hated what I was learning. It wasn’t until I got into high school and college that I started slightly enjoying school a bit more. Don’t get me wrong, I still hate all the exams and papers but I’ve come to learn it’s because of the lack of connection to the stuff I was learning about. There was a lack of representation of Black and Brown individuals in my education. I knew all about the great things White people did but never of Black and Brown people (other than Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks). And if there were mentions of great things white people did, it wasn’t until high school that I learned the reality of the repercussions of their actions. People like Christopher Colombus, Abraham Lincoln, and other romanticized white men, were praised for “achievements” that ultimately hurt people of color and continue to be celebrated. And this for me is such a huge problem. People of color have been forced to celebrate, assimilate with and acknowledge their oppressors. It was in high school and college that I first learned about how Colombus raped and killed indigenous peoples as well as him not actually “discovering” the Americas. Someone discovering something and someone colonizing someone else’s property, are two completely different things. Educators don’t really realize the importance of this historical moment because it affects all aspects of our lives today. The effects of colonialism, racism, and capitalism all are demonstrated in this very example and still are prevalent within our society today. These effects are instilled in the way we as a country go about situations, the way we treat people, the way we view people and so many other aspects. Students of color are disconnected from their cultural identities and practices because of the indoctrination and assimilation forced upon them. I never saw any mention of my cultural background unless it was from the U.S perspective and learning about mainstream news. But never were you shown the ugly sides of history, especially when U.S was in the wrong. I wasn’t aware of southern U.S. belonging to Mexico before the imperialist acts that the U.S. participated in. And this all comes down to the fact that our perception of others, our world and ourselves are distorted. Its all a means of controlling the way we as people of color, assert ourselves and identities out into the world. As a queer woman of color, it has been difficult to see the lack of representation of the success people of color have achieved. From revolutions to protests to creating children books with Black an Brown girls and boys, people of color have gone out their way to voice their realities and struggles. But if the educational system doesnt make the effort to supply students of color with those opportunities, how will they succeed?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reason to Live #5109

To be able to look back and say “I made it”. – Guest Submission

(Please don’t add negative comments to these posts.)

260 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thanks for being in the world today. Thanks for sharing yourself with us. ♥ Shop , Patreon , Books and Cards , Mailing List

10K notes

·

View notes