Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Your blog post is a thoughtful and inspiring reflection on the responsibilities and values that shape your role as a nature interpreter. I really admire how you emphasize connection, not just between people and nature but also within your audience's diverse experiences. Your approach aligns beautifully with Freeman Tilden’s principles of interpretation, particularly the idea of relating nature’s wonders to the lives of visitors.

To answer your question about my approach: while I share your commitment to fostering connection and inclusivity, I would also prioritize integrating mindfulness into interpretation. Nature often speaks to us when we slow down and truly immerse ourselves. For example, during a guided hike, I might encourage participants to pause, listen to the sounds around them, and observe how they feel at that moment. This reflective practice allows individuals to form their own, deeply personal connections to nature, which can be just as impactful as sharing facts or stories.

Additionally, I value the idea of co-creating experiences with audiences, especially in settings where diverse perspectives can enrich the interpretive process. Asking visitors to share their observations or memories of nature transforms interpretation into a two-way conversation, fostering a sense of shared ownership and curiosity.

Your mention of incorporating music resonated with me as well, it’s such a powerful tool for evoking emotions and creating connections. Perhaps blending mindfulness with sensory elements like music could add even more depth to interpretation. What do you think? Could mindfulness or co-creation enhance your already thoughtful approach?

Blog Post #10: Describe your personal ethic as you develop as a nature interpreter. What beliefs do you bring? What responsibilities do you have? What approaches are most suitable for you as an individual?

As I journeyed through this course and deepened my understanding of nature interpretation, I found myself progressively reflecting on the personal ethic that guided my approach. What beliefs do I bring to this work? What responsibilities do I have? How do I translate my unique personality and insights into a meaningful experience for others? These are questions that have shaped my learning and will continue to shape my practice as a nature interpreter.

At the core of my personal ethic lies the belief that nature interpretation is more than just educating or entertaining, it’s about fostering a connection between people and the natural world. As emphasized in Chapter 1, interpreters “enrich experiences by expanding awareness and understanding” (Beck et al., 2018). This resonates deeply with me, as I view interpretation as a bridge, a way to connect the visible wonders of the environment, like a towering oak tree or a meandering stream, with the intangible meanings they hold, such as resilience, interconnection, and history. This belief aligns with Freeman Tilden’s first principle of interpretation: connecting what is being described to something within the personality or experience of the visitor (Beck et al., 2018). For me, this means finding ways to make nature relatable. Whether it’s through a story about a bird’s migration or a hands-on activity that uncovers patterns in nature, I aim to create moments of revelation that inspire awe and curiosity.

As a nature interpreter, my role is to share knowledge in a way that is both captivating and easy to understand, while remaining true to the facts. This responsibility extends to ensuring that my interpretations are inclusive, acknowledging the diverse ways people experience and relate to nature. The concept of the “invisible backpack” mentioned in Unit 03 reminds me to be mindful of privilege and how it shapes access to natural spaces. For instance, not everyone has the same ability to engage with the outdoors due to historical, social, or economic barriers. Recognizing this as an interpreter involves crafting experiences that are inclusive and equitable for all. Furthermore, I am committed to ethical storytelling. This includes honoring the voices of Indigenous communities and other stakeholders whose histories and relationships with the land might differ from my own. Interpretation must be rooted in authenticity and a high regard for truth (Beck et al., 2018). For me, this means not only sharing the stories of the land but also questioning whose stories are being told and whose are being left out.

Given my learning style as a visual learner after completing the Unit 02 activity, “What’s Your Learning Style”, my approach to interpretation would gravitate towards using visual aids like diagrams, charts, and demonstrations. These tools not only help me process information but also allow me to cater to others who share this preference. However, I recognize the importance of adapting to different learning styles. Whether my audience consists of active learners who thrive on hands-on activities or reflective learners who prefer quiet contemplation, I aim to create a flexible interpretive experience. The constructivist approach described in Beck et al., (2018) informs much of my methodology. This approach emphasizes building new knowledge on visitors’ prior experiences, allowing them to construct their own meaning. For instance, while leading a guided hike, I might invite participants to share their observations and interpretations of the environment before offering further context. This approach honours their perspectives and fosters a sense of personal connection to their learning journey.

One of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned in this course is the importance of sense-making. Interpretation is not about delivering a lecture; it’s about creating opportunities for visitors to connect with the material in their own way. As stated in Chapter 1, “interpretive professionals are in the business of creating and managing opportunities for enjoyment” (Beck et al., 2018). This requires a deep understanding of my audience and a willingness to adapt based on their needs and interests. In practice, this means blending information with art and emotion. Unit 07 brought to my attention that music, for instance, offers a unique gateway to nature. The rhythms of a song can mirror the flow of a river, while the call of a loon can evoke a sense of solitude and wilderness. Drawing on these connections can make interpretation more memorable and impactful. Technology also plays a role in reaching larger audiences. Unit 08 emphasizes that while tools like apps and social media can enhance interpretation, they must be used thoughtfully to avoid detracting from the experience. For example, a guided tour might incorporate augmented reality to visualize historical changes in the landscape, but it should also encourage participants to engage directly with their surroundings.

Ethics in interpretation goes beyond the content I present; it shapes how I engage with others and the environment. Unit 03 mentions the precautionary principle, which inspires me to embrace a thoughtful and deliberate approach to interpretation, specifically when exploring sensitive subjects such as climate change or endangered species.These are areas where scientific uncertainty might tempt us to simplify or exaggerate information. Instead, I strive to present balanced narratives that empower visitors to think critically and act responsibly. Moreover, I see interpretation as a form of stewardship. By helping visitors develop a deeper appreciation for nature, I hope to inspire them to become advocates for its protection. The ultimate goal of interpretation is to cultivate well-informed stewards of cultural and natural heritage (Beck et al., 2018).

As I continue to develop as a nature interpreter, I recognize the need for ongoing reflection and growth. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, explored in Unit 09, serves as a guiding compass, illuminating my strengths while uncovering opportunities to grow and evolve. For instance, I’ve realized the importance of integrating risk management into my practice, as illustrated by the “Lemon Theory” in Unit 04. By anticipating potential challenges and preparing accordingly, I can create safer and more rewarding experiences for my audience. I am also inspired by the work of citizen science initiatives, as highlighted in the article by Merenlender et al., (2016). Through these programs, we witness the transformative power of collective action and how interpretation inspires a deeper commitment to environmental stewardship. Incorporating elements of citizen science into my practice could provide visitors with a sense of agency and a tangible connection to conservation efforts.

Overall, developing a personal ethic as a nature interpreter is a continuous journey, enriched by the wisdom I gather from this course and my own encounters with nature. My ethic is rooted in the belief that interpretation is about connection, connecting people to nature, to each other, and to their own sense of wonder. It is about creating opportunities for discovery, reflection, and action. As I move forward, I will continue to draw on the principles and practices I’ve learned, adapting them to suit my audience and the contexts in which I work. Whether through storytelling, visual aids, music, or technology, I aim to share my passion for the natural world in ways that inspire and empower others. After all, “interpretation opens minds to wonder and new ways of perceiving the world” (Beck et al., 2018). And what greater responsibility and privilege could there be than that?

References

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., & Knudson, D.M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World. Sagamore Publishing.

Merenlender, A. M., Crall, A. W., Drill, S., Prysby, M., & Ballard, H. (2016). Evaluating environmental education, citizen science, and stewardship through naturalist programs. Conservation Biology, 30(6), 1255–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12737

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey!

Your post beautifully captures the essence of nature interpretation as a blend of connection, education, and stewardship. I really admire how you emphasize storytelling, engagement, and accessibility, key pillars of fostering a deeper bond with nature.

If I were to approach nature interpretation, I’d focus on integrating technology into traditional methods to reach a broader audience. While I share your belief in hands-on experiences and storytelling, I see tools like augmented reality (AR) or interactive apps as ways to enhance engagement, especially for audiences who might not have easy access to natural spaces. For instance, imagine a guided hike where visitors can use an AR app to see how a forest might have looked 100 years ago or how it might look in the future based on conservation efforts. This would complement storytelling by providing a visual, dynamic layer to the narrative, making it especially impactful for visual learners.

Another approach I’d explore is incorporating personal reflection into the experience. After sharing stories or facts, I’d encourage visitors to pause and reflect on their feelings or memories tied to nature. Reflection fosters personal connection, making the experience more memorable and meaningful. It also opens up space for conversations, something you rightly highlighted as critical in nature interpretation.

Lastly, I’d prioritize co-creation with diverse audiences. Inviting participants to share their stories, cultural perspectives, or even lead parts of the experience fosters inclusivity and emphasizes the shared responsibility we all have toward nature. This approach aligns with your values of accessibility and engagement while adding a layer of collaboration.

What do you think? Could technology or reflection enhance the approaches you’ve outlined?

Unit 10 Blog Post

As I develop as a Nature Interpreter, my personal ethic entails having immense respect for nature and helping others foster the very same respect but through an engaging manner. Nature interpretation serves beyond providing facts but rather encouraging others to have the same emotions I feel when I view nature and help guide them to understand our duties and responsibilities to this planet.

One belief I bring is the understanding that everything in nature is interconnected. Now at this point you guys must be sick of me ALWAYS talking about the interconnectedness of nature but it is so vital to us. Understanding that everything in nature is interconnected, from the wildlife to the ecosystems to the environment helps us see the significance and beauty of how everything works together to create our planet, our nature. As humans, it may seem hard to understand the complex webs of relationships that exist within nature (human-wildlife, human-nature) but it helps us see nature more holistically as well.

Another belief I would like to touch on as referenced earlier, is our responsibility to the planet. As the current generation, it is our responsibility to ensure our future generation is able to live sustainably on the planet. In order to do so we must protect and preserve our resources. As a nature interpreter our responsibility to protect this planet extends into our jobs as well, because we have the ability to speak on environmental issues and bring awareness and also inspire others to help take action by just helping them engage with nature.

I believe accessibility to resources is crucial to society regardless of their socioeconomic status, age, race, gender, disability, etc. As a nature interpreter it is important to make sure our work should be accessible to others regardless of their abilities because our ability to help others invoke the feelings we want them to feel can be done even through something simple as story-telling as long as it is accessible to a diverse audience and can be engaging at the same time.

Another belief that aligns much with me as a nature interpreter is providing an open space for conversation. Often some treat nature interpretation as a “TED talk” where we talk a lot but there is no necessary area for conversation or questions. As a nature interpreter, it is crucial to provide an engaging experience which includes allowing others to have questions and to ensure they are answered. This allows us to build connections with the audience and also provides a comfortable area for everyone to learn from each other which is something they can take away into the real world as well!

As a nature interpreter, my primary responsibility is providing factual information. Providing misinformation goes against the very ethics and responsibilities I have as a nature interpreter and can be very harmful especially when it comes to issues such as conservation and climate change because it can discredit the entire movement and its significance to the general public, bringing down the overall support. It is also important to continue updating our “database” while more information becomes available because new information can invalidate certain facts very easily.

One belief of mine is that a nature interpreter’s key goal is to create an engaging experience but also to inspire. The interactive and engaging experiences I create with my audience should inspire them to form connections with nature and should help them feel open to fostering connections with those around them in order for the audience to share and pass on the knowledge they took away from this to take home as well. Our job is to provide visitors with a sense of place and help them recognize nature beyond it’s walls and see it for what it is in the overall scheme of things. Those special characteristics can be different for everyone but we should be able to help the audience find something that they can connect with in nature (a sense of place).

Another core belief of mine is ensuring my experiences as a nature interpreter should not cause harm or damage to the settings around me. For example, if I give a presentation as a nature interpreter in a wildlife park, my work can be engaging such as opening up the floor to the audience to have questions, or allow them to pet some animals that are allowed. In no way should my work cause harm to any animals or would it involve breaking rules simply to give my audience a fun experience. It is very important to help preserve the habitats our wildlife live in and in no way should the well-being of wildlife or environment be under harm.

There are many different approaches I have already explored as a nature interpreter but I will reinforce them again.

One approach as a nature interpreter that truly resonates with me is storytelling. As a child I loved reading because it allowed me to escape reality for a while and simply feel the perspectives of others. I especially loved to read books outside in the summer because it was warm, I always had a drink to refresh every few minutes and there was always a slightly cool breeze that followed to help me warm. As a nature interpreter, we always want to help our audience feel how we feel when we view nature. To me story telling is not only engaging, it is accessible to all audiences and it allows me to incorporate my personal experiences with nature as well as different cultural concepts in order to create an emotional connection between nature and my audience because it helps personalize the experience to them. In one such setting, a new park interpreter at Tyler State Park uses his love for storytelling and nature and incorporates them both to create the ultimate experience for his audience (Scott, 2024).

Another approach I like to use as a nature interpreter is incorporating different settings to create an engaging experience. My previous blog posts referenced going to places such as museums and parks and I believe that hands-on experiences helps the audience learn through different methods. Visual learners will appreciate having the ability to view nature through hikes or natural artifacts (fossils) from museums tours and auditory learners can appreciate the guidance that we provide as we help the audience understand each portion of the experience (facts on certain birds during hikes) and tactile learners can also benefit from hands-on experiences through safe contact with different artifacts and wildlife.

Question: I truly rambled a lot today but If you had your own approach to nature interpretation how does it differ from mine?

References

Scott, J. (2024). Exploring nature through storytelling: Meet Tyler State Park's new park interpreter. Tyler Morning Telegraph.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 6: Finding My Voice as a Nature Interpreter- The Wrap Up

There’s something magical about the bond we share with the natural world. Just today, I brought home a puppy, and within hours, it felt as though he had always been part of my life. My mom, initially hesitant about the idea, looked at him and said, “It feels like he’s known us forever.” This immediate connection reminded me of how deeply intertwined humans are with nature and its inhabitants. As environmental interpreters, we have the responsibility to awaken this sense of connection in others, nurturing a lifelong appreciation for the world we live in.

This connection aligns with Richard Louv’s reflections in Last Child in the Woods. Louv describes how his childhood adventures in nature calmed him, focused him, and excited his senses. He calls the woods his “Ritalin,” illustrating how nature has the power to heal and center us. Today, as interpreters, we face the challenge of reconnecting people with these experiences, especially in a world increasingly dominated by technology. From my puppy’s instant bond with my family to the awe of discovering wildlife in a forest, these experiences remind us that nature is not separate from us, it is a part of us.

The textbook Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World emphasizes storytelling as the cornerstone of effective interpretation. Facts alone rarely inspire action, but stories connect people emotionally to nature. For example, when teaching about the migration of monarch butterflies, it’s not enough to list facts about their journey. Instead, framing it as a heroic tale of perseverance and interdependence brings the story to life, sparking curiosity and compassion. Similarly, interpreters can share stories of their own experiences in nature to build a sense of shared wonder and connection with their audiences.

One example from the textbook that stood out to me was the story of a community revitalizing a polluted river. Instead of focusing solely on the science of cleanup, the interpretation centered on how people’s actions restored life to the ecosystem, from fish to plants to birds. These stories show that even small, localized efforts can create ripples of change, inspiring others to act.

This brings us to the responsibility of interpreters. Jacob Rodenburg likens the role of environmental educators to trying to stop a rushing river with a teaspoon. The challenges of climate change, habitat destruction, and biodiversity loss can feel overwhelming. However, as interpreters, our role isn’t to solve these problems single handedly but to empower others to take action. Rodenburg’s analogy reminds us that even small actions, like encouraging families to plant pollinator gardens or helping children identify birds, can create meaningful change.

One powerful idea from the textbook is the concept of “creating aha moments.” These are the moments when people feel a personal connection to nature, when facts transform into feelings, and curiosity blossoms into care. During a recent nature walk, I witnessed this firsthand. A group of children became captivated by an anthill, asking endless questions about how ants work together. Instead of lecturing, I encouraged their curiosity, letting their observations lead the conversation. Moments like these illustrate how interpreters can plant seeds of wonder that grow into lifelong stewardship.

To create these moments, interpreters must adapt their approaches to meet the diverse needs of their audiences. The textbook stresses the importance of tailoring interpretation to different cultural, social, and geographic contexts. For instance, in urban areas, where access to wild spaces may be limited, interpreters might focus on city wildlife like pigeons or street trees, showing how nature exists all around us. In contrast, rural audiences might connect more deeply with stories about local forests, farms, or waterways.

Hope is another essential element of interpretation. Richard Louv and David Suzuki emphasize the need to balance the urgency of environmental challenges with a sense of optimism. It’s easy to feel paralyzed by issues like melting glaciers, oceans of plastic, and endangered species. However, interpreters have the power to frame these challenges in ways that inspire action rather than despair. For instance, instead of focusing on the decline of pollinators, an interpreter might highlight success stories of communities planting pollinator gardens and witnessing the return of bees and butterflies. These hopeful narratives motivate people to believe that their efforts can make a difference.

Children, in particular, are central to the future of environmental stewardship. Louv points out that early experiences with nature shape a child’s relationship with the environment for life. Whether it’s introducing them to the song of a pileated woodpecker or teaching them to identify edible plants on a hike, these moments create a foundation of care and curiosity. As interpreters, we have a unique opportunity to spark this connection and foster the next generation of environmental advocates.

As this course wraps up, I find myself reflecting on the “so what” of environmental interpretation. What does it mean to be an interpreter in a world facing so many environmental crises? The textbook provides a compelling answer: interpretation is not just about conveying information; it’s about inspiring action. It’s about helping people see their place in the natural world and empowering them to protect it.

For me, this role is deeply personal. I’m motivated by a belief in the power of stories to connect people to nature. I’m inspired by the resilience of communities that come together to restore their environments, and I’m hopeful about the potential of children to become the stewards our planet so desperately needs. As interpreters, our job is to plant seeds of curiosity, wonder, and hope, trusting that they will grow into a more sustainable future.

The responsibility of an interpreter goes beyond simply teaching; it’s about fostering relationships between people and the environment. It’s about showing others that they are not separate from nature but deeply connected to it. Whether through a walk in the woods, a story about monarch butterflies, or a playful moment with a puppy, these connections remind us of the beauty and importance of the natural world. And in doing so, they inspire us to protect it, not just for ourselves, but for future generations!

Thank you for following along this journey with me :)

0 notes

Text

Hey! Your post took me right back to my own days as a kid, lifting rocks with that thrill of discovery! I’d find the same squirming piles of ants and feel a mix of excitement and a little “whoa, what’s happening here?�� Watching them move those tiny eggs so efficiently was like peeking into a hidden world of teamwork.

The idea that ants actually "farm" aphids and grow fungus like mini farmers is mind blowing! I never really thought of ants as complex creatures, but this completely changes the way I see them. How incredible that these tiny insects have their own versions of livestock and gardens, maintaining a whole system that’s been evolving for millions of years. That’s some impressive social structure for an insect we usually brush off as an annoying little thing.

Your point about us caring more for “charismatic” insects hits hard. It’s like a reminder of how easily we overlook creatures that don’t immediately appeal to us. We’re drawn to the bright colours and elegance of butterflies or beetles, but ants are like the unsung heroes, quietly keeping ecosystems running, often without our notice. Your post totally makes me want to dive deeper into learning about them. Thanks for opening my eyes to just how complex and incredible ants really are! It makes me wonder, do you think if more people knew about these amazing behaviours, we’d see a shift in how we view and value “less charismatic” insects like ants?

Unit 9 Blog #1

If you were anything like me as a kid, I bet you spent some time flipping over rocks and logs to discover tiny animals hidden beneath. Maybe you found salamanders, worms, and beetles, maybe something even more exciting for a young mind investigating nature for the first time. I can almost guarantee that something you found while doing this was a hectic, bustling colony of ants. I know when this used to happen to me, I would jump backwards, startled and somewhat unsettled by the squirming pile of tiny bugs, but as I became accustomed to this sight, I would notice how organized these insects seemed to be, gathering up the larvae and eggs and marching them into the tunnels to remove them from this newly exposed section of their home. After a while, I began to have an appreciation for these tiny workers.

As a group that is often overlooked and found to be more of a nuisance than anything else, ants aren’t usually the target of discussions promoting insects, although I hope some of this perspective can be changed eventually. It is much easier to sell a crowd on what we call the “charismatic megafauna” of insects. Things like praying mantises, monarch butterflies, and the large and colourful beetles of the world are easier to convince people to care about than flies, ants, or biting and stinging insects that people are predisposed to dislike. I believe that this could go into a deeper discussion about how we place more value on things that are more visually appealing or clearly benefit us, but that is another topic.

I’m going to delve into a couple of aspects of ant life that many people wouldn’t know about in hopes of instilling that just because these creatures are tiny and may be seen as a nuisance to us, they have been evolving and living their own complex lifestyles for such a long time, and deserve at the minimum respect (because despite my endearment for these little insects, I know this isn’t realistic to expect from others). I bet you never would’ve guessed that ants engage in agriculture! Some ant species keep other insects as livestock in the same way we keep cows. A group that can often be found in these livestock roles are Hemipterans, common name “true bugs”, funnily enough. Aphids are one example of Hemipterans often kept as livestock, and ants will feed them, take honeydew they produce for their own food (much like us milking cows), and even cull their population for protein when it is large enough. Other ant species are known to keep gardens of fungus or plants, some even going to the extent of producing herbicides to maintain these gardens and co-evolving with the gardened plant species.

Ants are so complex, and I truly encourage anyone interested to look into them more, and for everyone, perhaps consider why it is that we value those “charismatic megafauna” insects more than smaller, less visually appealing ones.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 9: The secret network beneath our feet 🌳🤯

Alright, let’s talk about trees. You’re out on a hike, breathing in that fresh forest air, maybe even feeling like you’re alone with nature. But you’re not. All around you, trees are having their own little conversations. Yep, these tall, leafy giants aren’t just silently standing there, they’re actually connected and communicating, sharing resources and even looking out for each other. It’s like the forest’s very own social network, except, instead of Wi-Fi, they’ve got roots and fungi.

Welcome to the “Wood Wide Web,” where trees are linked underground by a network of fungal threads called mycorrhizal networks. Picture these threads like nature’s own fiber optic cables. Through this underground web, trees can send each other water, nutrients, and information. Imagine two trees side by side, one gets hit by a pest, and it immediately starts sending out chemical signals through the network to warn its neighbors. Suddenly, trees nearby start boosting their defenses. They’re not just standing there, they’re helping each other survive. How cool is that?

And it gets even better. Some trees, known as “mother trees,” act like the wise elders of the forest. These trees aren’t just hoarding resources for themselves, they’re sharing with smaller, younger trees, especially their own offspring. They’ll send extra nutrients and water to give these young saplings a fighting chance. It’s like an ancient support system right beneath our feet, working to keep the forest community strong. Chapter 21 in The Bright Future of Interpretation talks about this kind of interconnectedness in ecosystems and how it changes the way we think about nature. Trees aren’t lone rangers, they’re teammates.

Discovering this hidden world of communication has flipped the script on how scientists view forests. Instead of seeing trees as separate entities fighting for survival, we’re realizing that the magic of the forest comes from its connections. It’s cooperation, not competition, that makes these ecosystems thrive.

I’ve been reflecting on this idea while working through my course, and it just keeps sparking more questions. If trees are communicating and working together, what other secrets does nature have? This is what keeps me fired up. I want to dig deeper and share these mind blowing insights in a way that gets people excited about the natural world.

When I first read the week 9 blog prompt, I was puzzled on what to write but then I started thinking about how to bring this kind of story to life for listeners. Imagine telling someone who’s never even been in a forest that these trees are all connected, like family, looking out for each other. It’s a powerful reminder that nature isn’t just a collection of things but a community. And the more we understand these connections, the more we can appreciate, and hopefully protect, the delicate balance within it.

So, next time you’re out in a forest, remember that the trees around you are connected and communicating. They’re helping each other, sharing resources, and creating a whole network of support. And maybe, just maybe, they’re telling us something too. Because, in the end, we’re all part of nature’s web.

0 notes

Text

Hey Chloe!

Your post beautifully captures how music and nature are intertwined. I completely agree that nature’s sounds such as the rustling trees, bird songs, crashing waves, and even thunderstorms hold their own form of music. It’s fascinating how cultures have incorporated these natural sounds into music, turning them into timeless art. You’re right that these sounds aren’t just background noise; they can be deeply comforting and inspiring, and they even connect us with the landscapes around us.

Your mention of Tilden’s principles highlights an essential part of nature interpretation which is blending art with education to create emotional resonance. When music draws on natural sounds or evokes landscapes, it becomes a powerful interpretive tool, bringing listeners closer to nature even when they’re far from it. Ben Mirin’s work as a “wildlife DJ” is a perfect example of this, as he uses bird songs to create music that educates and inspires empathy for wildlife.

“Good Days” by SZA is an AMAZING choice for evoking nature’s tranquility. I also chose this because every time I listen to it, it feels like a calm day somewhere in nature. Her lyrics and the dreamy vibe truly capture that feeling of peace you described, much like a sunset walk by the ocean. You can never go wrong with listening to any of her songs wherever you may be. Your picture perfectly reflects this idea, too! A quiet moment that reminds us of the calming influence of nature, helping us focus on the good days ahead. Thanks for sharing such a vivid and personal perspective!

Unit 07 blog post

Hi all,

To answer the question, “Where is music in nature?” and “Where is nature in music?”, I think there is more than one response. Music in nature can be found, in my opinion, quite literally everywhere. Whether that is the sound of trees rustling on a windy day, birds communicating while flying overhead, waves crashing into each other, or even rain during a heavy thunderstorm. Although this isn't quite like the music we like to listen to on our headphones every day, I find it can still be just as enjoyable. These natural sounds can even inspire the composition of music we hear today. Many different cultures across time have incorporated animal sounds, fire sounds, and many more natural melodies into their own musical traditions. It goes to show that music and nature are intertwined with one another.

Many natural rhythms are influenced by the sound of the sea, wind, and rain, which serves as a reminder of how deeply ingrained nature's melodies are in music. According to the article by Gray et al. (2001), musical sounds observed in nature indicate a connection between any living things, and that this relationship can be understood as a shared language among species. On the other hand, when it comes to music, there is so much more to reflect on when it comes to nature rather than just purely imitating the sounds. Composers often write their music according to the landscapes they see. This includes mountains, lakes, or even a thunderstorm. It can be a way of portraying the place, where the listeners feel themselves there when they are far from it. For songwriters who have enough talent to capture the wide range of feelings, narratives, and visual beauty found in nature and transform them into sound, it can be a constant source of inspiration. For artists, songwriters, and composers, nature is an endless source of inspiration. It offers a variety of feelings, stories, and visual beauty that may be transformed into sounds. Tilden's principles state that interpretative programs that combine art and information can have a profound emotional impact that leads to a sense of connection with nature, which should then inspire responsibility. Incorporating bird melodies into beatboxing is one example of how Ben Mirin uses his skill to capture the sounds of specific species. This gives audiences a new perspective on animals and ecosystems that they might never get to see firsthand.

One song that immediately takes me back to a natural landscape is “Good Days” by SZA. The reasoning for this is that I find the song to be really dreamlike as if I’m walking on a beach at sunset or nighttime. SZA has been one of my favourite artists for a long time so I am definitely also a fan of her voice, in this song specifically. The song is about how even though things might be tough right now, “good days” are coming. I love the meaning of this song because it is a reminder to not be more present and to not focus too much on the things that stress us out in life.

This is a picture I took two summers ago, walking along the beach at around 11pm, listening to "Good Days". I love this picture because even though the quality is not the best, it takes me back to that time when I felt so at peace :)

Thanks for reading!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 7: Music in nature 🎼🏔️

As nature interpreters, our goal is to engage our audiences in meaningful ways. The tools we use for this engagement may vary based on factors like weather, group size, and our own skill sets. This week, we're diving into an intriguing approach: interpreting nature through music. While some may initially claim they know little about music, it's often surprising how much we can draw from our experiences and insights.

Music plays a pivotal role in environmental interpretation, transcending basic entertainment to evoke emotions and inspire action. In many cultures, music, stories, and dances serve not only to celebrate but also to educate and inform. In Canada, we often separate arts from education, with interpreters typically leaning toward entertainment or information. However, the most effective interpretive programs seamlessly blend the two, stirring hearts and minds and inspiring stewardship of our natural spaces.

Every known human culture has music, defined as patterns of sound produced for emotional and cognitive purposes. But it’s not just humans who create music. Animals use sound for communication, establishing a profound connection across species. This invites intriguing questions: Can other species create a musical language? How do musical sounds foster communication in the animal kingdom? The bonds revealed through musical sounds highlight our shared existence and the necessity of protecting our environment.

Tilden's third principle of interpretation states, “Interpretation is an art, which combines many arts.” This principle invites us to explore the integration of music in our programs. Incorporating music into nature interpretation can make experiences richer and more memorable. For example, consider the impact of a local artist's song that captures the essence of a landscape, making it resonate deeply with the audience.

The power of music can also be seen in the story of Ben Mirin, a musician who combines beatboxing with birdsong recordings to create engaging performances. By merging these sounds, he captivates audiences and fosters a connection to wildlife. His work as a "wildlife DJ" inspires listeners to appreciate the beauty of nature through an innovative lens.

Personally, one song that instantly transports me to nature is “Good Days” by SZA. The song's serene melodies and reflective lyrics evoke imagery of sunlit trails and afternoons spent outdoors. I can almost feel the gentle breeze and hear the rustling leaves as I listen. It reminds me of lazy summer days, where time slows down, and nature's beauty unfolds around me. The lyrics, filled with hope and introspection, resonate with the way nature can inspire contemplation and peace. In this light, we must remember that nature interpretation is about connection. Music can serve as a bridge between people and the natural world. The songs we share can evoke memories and experiences we cherish.

As we explore this week, let's embrace the transformative power of music in nature interpretation. Share your favourite nature-inspired songs and the stories behind them, and consider how music can enhance your interpretive practices. The journey of discovery awaits, and through music, we can create deeper connections to the landscapes we cherish and the creatures that inhabit them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hey!

Your reflection on Hyams’ quote beautifully connects the idea of continuity between the past, present, and future with the dynamic nature of environmental interpretation. I particularly resonate with your observation that artifacts from the past, or natural environments, aren’t valuable simply because they are old or unchanging. Instead, it’s the "integrity" of their ongoing story, shaped by time, that gives them meaning. This ties in well with the idea from the unit that nature is a living entity, constantly shaped by history but always evolving.

Your personal story about being a camp counselor adds a compelling, personal touch to the discussion. I love how you connected your sense of place to the realization that the environment you experienced wasn’t static, but part of a larger narrative. It’s a perfect example of how history, whether geological, ecological, or even personal, gives deeper meaning to our interactions with nature. It reminds me of how often we overlook the layers of history that exist in a natural space until we reflect on our place within it.

I’ve also had moments when returning to a familiar natural setting felt like reconnecting with its past. For example, when revisiting a trail I used to hike years ago, I could feel the weight of all the experiences that had taken place there, not just for me, but for countless others over time. This awareness of the continuity of the environment gave me a deeper sense of connection, much like your return to camp. Have you noticed similar feelings when revisiting places that once felt solely your own?

unit 06 blog post

Hyams discusses continuity between the past, present, and future in this quote, highlighting how crucial it is to uphold the integrity that unites all the components of an experience over time. Starting off with the statement that there is "no peculiar merit in ancient things," the quote casts doubt on the notion that artifacts from the past are worth anything just because they are old. Rather, "integrity," or the entirety and continuity of knowledge and experience over time, is what really matters. Maintaining links between various components, even if they are dispersed throughout time, is what integrity is all about. Connecting this quote with our textbook, I think it implies that our comprehension of nature shouldn't be static when it comes to environmental interpretation. Instead, we must acknowledge that nature is a dynamic, living thing that is shaped by the past but is constantly changing, much like history.

This viewpoint is consistent with the teachings covered in this unit, which emphasize the importance of history in understanding nature. The passage stresses the need of keeping a "memory of ancient things," and this section focuses on how historical interpretation enables us to make connections between historical landscapes, events, and artifacts and our current understanding of nature. It's not enough to simply observe the natural world as it is; one must also comprehend how natural occurrences, human history, and societal shifts have shaped it. As history gives our relationships with nature life and significance, it promotes a stronger feeling of place and community.

I can’t help but think of when I initially fell in love with the environment around me during my summers as a camp counsellor. It was all so new to me, so much so, that these places seemed to belong to me now, existing just if I was present to experience them. However, as time passed and I thought back on my sense of place, I came to see that those locations' beauty had more to do with things than just my presence. They were intricately linked to a greater narrative that began long before I arrived and continued long after I left.

Photo of my Camp during my counsellor days.

The quote's last line, which draws a comparison between forgetting the past and believing that a train station only exists while a train is there, serves as a great metaphor for how people frequently approach the world of nature. I felt this way when I returned home from camp to the city, that the environment simply was less existent, however that is not the case. It doesn't mean that nature disappears or becomes less important just because we don't continuously see it or engage with it. It is important for us to recognize that the environments we explore have complex histories, whether they be geological, ecological, or human, and that these histories continue long after we are gone. I see this idea to show us as interpreters how to view our environmental surroundings as parts of a continuous story rather than as discrete points in time.

After visiting camp recently I found I felt a sort of "past" connection to its environment, I wonder have you ever experienced a stronger sense of connection to the past or future of nature?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 6: Connecting Past and Present: The Enduring Influence of History

Edward Hyams' quote from The Gifts of Interpretation reminds us that the past is not something separate from the present, rather it is a continuous thread that influences how we think, feel, and act today. To view the past as irrelevant is like believing a railway station ceases to exist the moment we leave it, an illogical and narrow perspective. Nature, history, and human experiences are interconnected across time. Integrity, as Hyams suggests, is about keeping these parts connected, ensuring that history and memory are preserved and integrated into how we interpret and engage with the world.

When we apply this thinking to nature interpretation, it highlights the importance of recognizing the historical layers within a landscape. The trees, rivers, and wildlife we observe today are shaped by centuries of natural processes and human interaction. Interpreting these spaces without acknowledging their historical context would provide an incomplete picture. For example, when we walk through a forest, we may admire its beauty, but understanding the role of Indigenous stewardship, conservation efforts, or past environmental damage deepens our appreciation and awareness.

The role of history in nature interpretation is to offer a fuller, more nuanced view of the landscapes we engage with. It helps us understand how the land has evolved and what forces (both natural and human made) have shaped it. This historical lens also encourages us to consider our role in shaping the future. By acknowledging that landscapes are not static and that human actions influence the environment, we take responsibility for the preservation and stewardship of natural spaces for future generations.

In writing about nature, particularly through an interpretive lens, Hyams’ emphasis on integrity is crucial. Effective interpretation must not only tell the story of what we see today but also connect it to the past and consider how it might change in the future. This requires a thoughtful approach to history, one that includes the voices and experiences of those who have been connected to these landscapes before us. Ignoring these elements would result in a shallow, fragmented interpretation, failing to capture the full complexity and richness of the environment.

Interpretive writing, whether it appears in signage, guidebooks, or blogs, serves as a bridge between past and present, inviting readers to see themselves as part of an ongoing story. As interpreters, we are tasked with maintaining the integrity of that story, ensuring that no part is lost or overlooked. This means telling the stories of not just the land, but also the people who have shaped it, whether it's through exploitation, conservation, or cultural significance.

In conclusion, Hyams’ quote serves as a reminder that history is not confined to the past. It lingers, shapes, and informs the present. By maintaining the integrity of the past through interpretation, we create a richer understanding of the natural world and our place within it. Just as the railway station continues to exist after our train has passed, history continues to shape our lives, and it is our responsibility to honor and preserve that connection!

Thank you for reading my perspective :)

0 notes

Text

Wow, you captured such a good picture of the northern lights! What an incredible experience! I also was able to see them yesterday. It's fascinating to witness, especially in a place like Guelph, which must have been more clear there than where I am. Your description of the deep pinks, emerald greens, and navy blues lighting up the night sky accurately captures the beauty of nature. I can't stop thinking about how breathtaking that moment was, especially with the stars as the backdrop.

It’s amazing how something so beautiful can also be explained through science. The way you tied in the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetic field adds so much depth to the experience. It’s fascinating to think that these stunning light displays are the result of charged particles colliding with gasses like oxygen and nitrogen. Knowing the science behind it doesn’t take away from the magic, it actually makes it even more impressive!

Your post really resonates with the idea that nature offers us a chance to pause and reflect. Like you said, moments like these force us to slow down and appreciate the world around us. I love how you referred to the Aurora Borealis as nature’s “Gift of Beauty,” because it truly is a reminder of the peace and stillness that nature can bring. I also wrote about how nature helps us escape from life’s stresses, so I completely agree with you on the power of nature’s beauty to clear our minds and restore our sense of calm!

Unit 05: Blog Post

This week's post is an open-ended post, and I wanted to share one of the coolest experiences that I had the other night. I am always in awe of nature and its beauty; however, last night I was totally blown away but nature in the most incredible way. I was fortunate enough to see the Aurora Borealis in Guelph, I left with with my girlfriend a just after 8pm and drove north towards Fergus, we waited on a side street for a couple hours with the lights off eating snacks and waiting, and then we saw them…

This image was taken out of the sun roof of a car, on the side of a road, In the middle of nowhere, around Guelph.

These incredible colours and lights in the sky, it was magical. I have not seen anything like that before, the deepest pinks and emerald green and navy blues, that light up almost pitch-black starry sky. For those who may not know, the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) are a naturally occurring light display that is usually able to be seen in high-latitude regions around the Arctic and Antarctic and most of northern regions of Canada.

As a science major, I was obviously extremely curious about how these lights in the night sky came to be, and I came up with this. The Aurora Borealis isn’t actually magic but is primarily caused by the “solar wind” which actually consists of charged particles (mostly electrons and protons) that are released from the sun, by “solar flicks”. When the “solar wind” approaches Earth, it interacts with our planet’s magnetic field caused by the north and south poles. (Haerendel (2022)). This field acts as a “shield”, in turn directing the charged particles towards these polar regions. As the charged particles enter the atmosphere, they collide with gases like oxygen and nitrogen at high altitudes, these collisions transfer energy to the gas molecules, exciting them. When these excited gas molecules are returning to their normal state, they release energy off in the form of light, creating the stunning displays we see of bright colours and waves. (Haerendel (2022)).

The aurora borealis isn’t just visually stunning; it evokes feelings of joy, tranquility, and awe. This beauty is a gift that encourages us to slow down and find solace in the natural world. In a society that often values speed and efficiency, moments spent under the northern lights remind us to cherish stillness and reflection. The aurora borealis isn’t just a pretty sight; it’s an opportunity to connect with nature and reflect on our place in it, you just stare in amazement and forget about other things as nature shows that it can claim all your attention. That is natures “Gift of Beauty” for todays post.

I wanted to share this beauty with everyone who views my feed, although I spoke a lot about science in my blog today, I am still blown away by the “Gift of Beauty” in nature. I am always learning new things and today I learned about the Arouca borealis as I was captivated by the beauty of these northern lights.

Reference:

- Haerendel, G. (2022). My dealings with the aurora borealis. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2022.1033542

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog 5: "Nature Therapy"

Life can get overwhelming fast. Between family, relationship issues, or bills, it often feels like there’s no way to hit pause. That’s where nature offers a simple, powerful way to step away from it all and recharge. Whether it’s taking a peaceful walk, paddling out on a quiet lake, or getting lost in a scenic vacation spot, nature has this incredible ability to help us escape the chaos and find calm.

We often underestimate how much fresh air and greenery can affect us. Walking through a forest or sitting by a river can do wonders for our mental health. Spending time in nature has been shown to reduce stress levels by lowering cortisol, the hormone that triggers anxiety. In fact, doctors are increasingly recommending “nature therapy” as a form of treatment for patients dealing with depression, anxiety, and stress. The simple act of being outdoors, hearing the wind in the trees, birds singing, or water flowing, can bring us back to a state of calm that’s hard to find in our fast-paced lives.

There’s a concept known as “biophilia,” which suggests that humans have an inherent connection to nature. It explains why we’re naturally drawn to green spaces and why being surrounded by nature has such a soothing effect on our minds. It makes sense! our ancestors lived in nature for thousands of years, relying on it for survival. While modern life has pulled us away from that natural world, our minds still respond positively when we reconnect with it. Nature offers us the space to slow down and let go of the mental clutter we carry around.

For those who like to stay active, nature also provides an opportunity to combine physical exercise with mental relaxation. Canoeing, hiking, or biking through a forest trail isn’t just a great workout, it also takes your mind off whatever’s weighing you down. When you’re out on the water or climbing a mountain, your brain switches from worrying about everyday problems to focusing on the task at hand. Plus, the endorphins from exercise, the “feel-good” chemicals our body releases, naturally lift your mood (Laguaite, 2021).

Laguaite, M. (2021, April 13). Nature Therapy: Types and Benefits. WebMD. Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://www.webmd.com/balance/features/nature-therapy-ecotherapy

0 notes

Text

Hey! Thank you for sharing and I totally agree with how you see the connection between nature and art, they really do go hand in hand. I also think capturing nature through art is about more than just the landscape, it’s about expressing the feelings and deeper meanings behind it. As someone who loves creating art of scenic landscapes, I feel like it gives me a way to share the beauty I see in nature with others, and it’s a deeply personal way to interpret what’s around us.

Your point about art being subjective really stands out to me. Everyone has their own perspective, and that’s what makes it so special. It’s interesting to see how different people interpret the same scene in their own way, and how our personal experiences with nature shape the final artwork. Sometimes, what feels like an ordinary moment to one person might be something deeply beautiful or emotional to someone else.

I also love that you brought up the Group of Seven. Their work has definitely shaped how people see Canadian landscapes, and it’s amazing to think that art can preserve those scenes for future generations. The way you talk about the “gift of beauty” being both something we see and feel is spot on. Art really helps capture those emotions that are sometimes hard to put into words. By interpreting nature through art, we create lasting connections and can share those moments with others!!

Unit 4 Blog Post

Who are you to interpret nature through art? How do you interpret “the gift of beauty”? (Your readings – specifically Chapter 5 of the textbook – will be helpful for this!)

Art has always held a special place in my heart, whether it is painting, photography, drawing, or just going to museums to see what others have created. When considering nature interpretation, it is very clear to me that the two go hand-in-hand. Nature and art are the same thing. This is obvious to me when I see my friends' Instagram stories flooded with pictures of a pretty sunset, or when I stop to take pictures of cool mushrooms I see while on a walk. It is very easy to interpret nature through art because they are synonymous. As a nature interpreter I am able to describe the beauty of nature while out in the field, but also by analyzing depictions of nature in art. Being able to convey what an art piece is telling us about nature we are able to interpret nature to its fullest extent.

In my free time I enjoy going to parks near my house and painting what I see. I believe that this is a very important way of interpreting nature as you are capturing it through your perspective. As we know, art is subjective. Due to this everyone identifies with it differently. By painting, photographing, or drawing nature we are able to share how we see it and share our interpretations when words may fail.

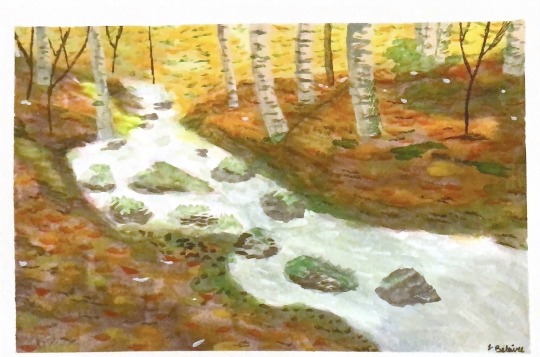

My interpretations of nature through paintings I have done

Personal interpretations of nature through art have existed for centuries with many of the “most famous” paintings of all time being depictions of nature (like Monet’s Water Lilies). The Group of Seven have also created many paintings that portray the beauty of nature as discussed in this week's unit. Through their art, the members of this group were able to capture the beauty of Canadian landscapes to share with the world. Their paintings convey the stillness of lakes, blowing winds, and colours of fall among other things. Each one is a snippet of the environment Canada has to offer and their work is a very prominent part of Canadian heritage. Growing up I remember taking countless field trips to the McMichael Canadian Art Collection gallery with my school. I remember myself and my classmates being astonished by the feelings that these paintings evoked, and even taking time to draw our versions of some of them. By observing these pieces of art and creating our own based off of them, we were able to experience scenery that some of us had never seen before. We were able to get a sense of what it was like to be there without ever leaving the walls of the gallery.

Harris, H. S. (1928) Lake and Mountains [Painting]. I remember recreating this painting specifically

In regards to the “gift of beauty”, I believe that it is hidden (or not so hidden) in nature. We can see the visual appeal of a pretty flower or fall leaves in a forest, but we can also feel it. The beauty of nature comes with emotions; when we imagine a still lake it brings calmness, and when we think of a bright summer day it brings joy. The gift of beauty in nature is the escape that it offers, not just the pretty colours and cute fuzzy animals. By interpreting nature through art we are able to capture that gift and save it for future generations to see, just like the Group of Seven did.

A picture I took in Australia that encompasses the gift of beauty for me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 4: Nature Interpretation through Art

Interpreting nature through art has always been a deeply personal experience for me. I’ve loved drawing scenic landscapes for as long as I can remember and creating art around nature. While my hand can never fully replicate the magic of the scene, the process itself feels like a way of engaging with the natural world in a meaningful way.

But when I think about who I am to interpret nature through art, it’s easy to feel uncertain. Art often seems like it belongs to professionals, to those who have formal training or are recognized for their talents. However, what I’ve come to realize is that interpreting nature through art isn’t about technical skill. Instead, it’s about observing, feeling, and translating those experiences into something others can relate to. Art provides a way to share my perspective, to help others see what I see, and to convey the beauty of nature as I experience it.

In Chapter 5 of our textbook, we explore the concept of “the gift of beauty.” To me, this idea speaks directly to what art does. It allows us to capture something fleeting, like a sunset or a misty morning, and make it last a little longer. This process is not just about remembering these moments for ourselves but sharing them with others. I often find myself taking photos of landscapes or sketching quick drawings because I want to extend the experience and, hopefully, offer others a glimpse into that beauty.

This idea of capturing and sharing beauty through art is reflected in the work of artists like the Group of Seven, who are discussed in our course. Their paintings of Canadian landscapes weren’t just depictions of physical places, they were emotional and symbolic interpretations of nature that shaped Canada’s national identity. While my art may not have the same historical significance, the act of interpreting nature still holds immense value. It allows me to express my personal connection to the environment, and in doing so, invite others into that experience.

Art also offers a way to convey deeper meanings behind natural elements. For example, a tree isn’t just a tree in art; it might symbolize life, resilience, or the passage of time. A mountain could represent strength, endurance, or the challenges we face. Through art, we can layer these symbols and emotions onto nature, allowing us to communicate our thoughts and feelings in a way that goes beyond words. This makes art a powerful tool in nature interpretation because it taps into both intellectual and emotional understanding. Art is not just about creating beautiful things but about fostering connections. It can evoke emotions and offer new perspectives, helping people to see the natural world in a new light, which is what nature interpretation is about, helping others to connect with and appreciate the environment around them.

By using art, I can share the gift of beauty in nature, helping others to see the significance in a landscape or a single tree. It’s not about being an expert or a professional artist; it’s about seeing the world and sharing that vision with others.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey!

I really love how your post breaks down the idea of privilege in nature interpretation. It’s something that a lot of people don’t think about when they talk about “getting out into nature.” You’re so right, many of us just assume everyone can access the outdoors in the same way, but that's far from true. Whether it's due to money, geography, or even cultural background, the way we experience nature varies a lot, and those differences are rooted in privilege.

In my post, I touched on a similar idea, especially when it comes to who feels safe and welcome in natural spaces. It’s not just about physically getting to these spaces, but also about feeling included when you’re there. Your mention of people living in low income areas not having the same access to outdoor experiences really connects to my own thoughts on how privilege shapes not only access but our whole relationship with nature.

When we both talk about privilege in this context, it really highlights how important it is for nature interpreters and educators to consider these barriers. It’s not enough to just invite people into these spaces, we need to make sure they feel like they belong there too. And that means creating more inclusive programs that take into account different backgrounds and experiences. At the end of the day, nature should be something everyone can enjoy, not just those with the means and privilege to do so easily!

Thanks for sharing :)

Unit 3 - Privilege in Nature

My definition of nature interpretation would be spreading knowledge and conveying nature's significance in our world. This information is often shared through services, programs and personal interactions. There is often a misconception that everyone can experience nature the same way. However, this is not the case and many people are not allowed to experience discover nature the same way as others. This is where the concept of “privilege” comes into play, ultimately by understanding how different people access nature.

When defining privilege we take a look at advantages that are given and the opportunities or rights that an individual has due to their social class. These advantages are often overlooked by those who are already given these opportunities from the start, but the same opportunities can make a significant change in the lives of those who are not fortunate enough to even have a glimpse of those opportunities. Privilege is also affected by various factors such as economic status, education and geographical location. One of these factors is displayed when an individual grows up in a wealthy urban environment where it is not difficult to access education and safe outdoor environments. Whereas it might be difficult for someone living in a low-income community to obtain the same opportunities.

Additionally, a significant way privilege affects nature interpretation is through the opportunity to explore natural spaces. Not everyone has the luxury of accessing these natural spaces. Many natural tourist marks are located far from urban areas, which makes it challenging to visit. Many people don't have the finances for transportation, admission or even the time to visit due to the distance. Whereas wealthier individuals may have more of an opportunity to visit these sites because they have the finances that can afford to take these trips to go and explore the natural sites where they can deepen their knowledge about nature.

Privilege tends to play a role in shaping how people understand and value nature. The background of education and life experiences all factor into how an individual might interpret nature. Someone who has background knowledge of environmental sciences or outdoor experiences may value nature more because they understand the scientific importance it has on the environment. Whereas an individual who was living in an urban environment with very little access to nature would view nature with less significance and might not even have a connection with nature as a whole.

Furthermore, cultural views towards nature differ greatly. In certain communities, nature may play a more important role due to spiritual significance, while in other communities it is seen as a place used for economic gain. These interpretations are influenced by privilege, as where individuals with greater cultural significance tend to have more historical and spiritual knowledge reflected in mainstream environmental conversations. This can create a disconnect for those with a different relationship with nature, where their diverse connections are underrepresented.

Acknowledging the role of privilege in nature interpretation is crucial to making outdoor education and recreation more inclusive for all individuals. Nature interpreters, educators and environmental groups have to understand the differences in individual experiences and access to natural sites and nature. By offering a program that is more diverse and inclusive towards underrepresented communities, they can overcome the disconnect and create a space where an inclusive understanding of nature is offered.

Privilege plays a critical role in how individuals access and interpret nature. By acknowledging the disparities in access, cultural attitudes, and representation, nature interpreters can work towards creating more inclusive, equitable experiences for all people. Nature belongs to everyone, but it is the responsibility of those with privilege to ensure that its beauty, lessons, and significance are accessible to all, regardless of background or status.

Lastly, including indigenous knowledge and history in nature interpretation can create a diverse experience that expands the knowledge of indigenous cultures to all individuals. Understanding the importance of nature, meaning and values for different individuals allows for a more inclusive approach to interpretation altogether.

A photo I took of an Inukshuk symbol near a nature site in Ontario, where I learned about the historical roots the symbol has with the Inuit culture.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blog 3: Privilege in Nature

As I continue on my journey as a nature interpreter, I find myself fascinated with the concept of privilege and how it shapes my role in environmental education. Privilege, in my view, refers to the unearned advantages and opportunities afforded to certain individuals or groups based on their social identities such as race, class, gender, and education. This invisible backpack of privileges can significantly influence not only our interactions with nature but also our ability to connect with diverse audiences.

Reflecting on my own experiences, I recognize that my background has provided me with opportunities that others may not have. As a person with access to quality education, I have had the privilege of learning about environmental issues, conservation, and the complexity of nature interpretation. This knowledge allows me to engage confidently with audiences, whether they are school children eager to explore the outdoors or adults seeking deeper insights into ecological processes. However, I must acknowledge that not everyone has had the same access to education or exposure to nature, which can create barriers to understanding and appreciation.

However, it’s crucial to remember that not everyone shares the same experiences. It’s essential to remember that my audience comes from diverse backgrounds. For example, a family from an urban setting may have completely different experiences and expectations than a group of seasoned hikers. As interpreters, we have to be adaptable and sensitive to these differences, creating a welcoming space that encourages everyone to participate and learn

Furthermore, risk management is a critical aspect of my role as an interpreter. The balance between risk and reward is especially relevant when leading outdoor activities. An example would be the Timiskaming Tragedy which is a moving reminder of the responsibilities we carry. It makes us think about the risks we ask others to take and how our assumptions about their capabilities can shape their experience. Not everyone has the same level of comfort in outdoor settings, and understanding this can help us be more thoughtful in our planning and execution.

Understanding the significance of privilege also compels me to examine the ethical implications of my role. As interpreters, we are in a unique position to shape narratives and influence perceptions of nature. This power comes with a responsibility to uplift marginalized voices and promote equity in environmental conversations. Engaging with diverse perspectives not only enriches our understanding of the natural world but also fosters a sense of belonging for those who may feel excluded from these spaces.

So, what’s the takeaway? Privilege is a complex topic that plays a significant role in nature interpretation, shaping our identities as interpreters and our connections with diverse audiences. By unpacking our invisible backpacks and acknowledging the advantages we hold, we can strive to create inclusive and meaningful experiences for all. As I continue my journey in environmental education, I am committed to fostering an environment that not only celebrates nature but also recognizes and addresses the diverse needs and backgrounds of my audience. This commitment will not only enhance the educational experience but also contribute to a broader movement towards equity and inclusion in the field of nature interpretation.

0 notes

Text

Hey!

I really resonate with your vision of being an environmental interpreter, especially your focus on interactive and hands-on learning in a natural setting. Like you, I find that a tactile approach to engaging with nature can make the experience more memorable and impactful for audiences. It’s incredible how you want to create a connection between visitors and the environment through direct interaction, which I also think is key to fostering a deeper appreciation of nature.

Your emphasis on adaptability and communication really stood out to me. In my ideal role, I also imagine needing to tailor my message to various audiences, whether it’s explaining climate change concepts or promoting nature conservation. Being able to adapt to different learning styles is something I’m working on, especially since it plays such a crucial role in ensuring everyone walks away with a meaningful experience.

I also admire your focus on active engagement in the outdoors. For me, daily walks through trials and observing wildlife has been a way to stay connected with nature. I hope to bring that same sense of wonder and connection to others, just as you plan to in your role. I think we both share the goal of fostering a deeper connection to nature, and I’m inspired by how you want to make that experience interactive and memorable for everyone you encounter. Thank you for sharing!!

unit 02 blog post

As an environmental interpreter, my dream position would consist of being interactive and practical, with a setting that promotes face-to-face communication. I see myself succeeding as a facilitator in a dynamic outdoor education centre or national park, where my tactile learning style and active engagement techniques can come to life.

I do best in dynamic circumstances where I can interact physically with my surroundings because I am a tactile learner. I might offer interactive tours and seminars encouraging guests to touch, investigate, and actively participate in a natural park where I work as a facilitator. These might be anything from courses on conservation to nature hikes and wildlife observation; the idea is to make learning a real and memorable experience.

My days in this role would be spent interacting directly with the natural world. I could fulfill my need for physical activity and efficiently teach knowledge through these activities, which range from illustrating ecological processes to helping with habitat restoration initiatives.

Strong communication skills are necessary for this position to explain difficult environmental ideas in a way that is understandable to people of various ages and learning preferences. Another important quality is adaptability, which enables me to modify programs in response to group comments and participation levels.

Ultimately, a facilitator's job is to create a bond between people and the natural environment. To inspire each visitor to take an active role in the environment's preservation, I want to have given them a greater appreciation and understanding of it. This position is truly a chance to have a long-lasting effect on people and the environment, which fits in well with my love of the outdoors and tactile learning styles.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 2: Ideal Role

In my ideal role as an environmental interpreter, I envision working at the intersection of climate change awareness and nature conservation. This role would be rooted in both education and action, where I could engage diverse audiences to help them understand the impact of climate change on natural ecosystems and empower them to take part in solutions. I see myself working in a national park, conservation area, or community-based organization that focuses on environmental stewardship.

One of the main aspects of this role would be to create experiences that connect people with the natural world in a meaningful way. I would aim to communicate the urgency of climate action, but in a way that fosters hope rather than fear. This is where interpretive skills come into play! being able to engage my audience emotionally and intellectually by weaving together facts and stories that resonate with them. For example, while leading a hike, I could discuss how rising temperatures are affecting plant and animal species in the area, highlighting real-life examples of resilience and adaptation. By sharing stories of ecosystems adapting to climate change, I would aim to foster a deeper connection between visitors and the environment, motivating them to protect it.