Text

Open, closed, open

2017

What I want you to know is how much I miss your feet sometimes, the way you stood on this earth, slender toes widely spaced, skin soft and tan and tender. I miss your feet in dirty scuffed slippers, I miss them in the sand, I miss them tucked up against my legs on the couch. What I want you to know if that I miss you half-awake in the morning, hair swirling, yesterday’s mascara smudged in flecks beneath your eyelids. I miss pouring coffee for you, miss spending all morning in pajamas with you, miss asking questions and telling stores and wondering- just wondering, marveling. I miss feeling with you. You were like some kind of lightning rod for feeling, an open channel, you felt it all. How did you keep from closing your heart? What I want you to know is that I’m seeing all the ways I closed mine, as if I might protect you- us- from all that feeling. And when I find the doors stuck shut, I lean against them, press my forehead against them, listening, softening, loving the door, thanking the door. When I can, I open them. Usually I want to close them again right away. It’s uncomfortable.

This summer, I find myself in relationship with the windows of my house, opening them wide at night, sleeping in the cool breath of the darkened earth, and then closing them in the morning, capturing the coolness behind thick dark drapes so that when I come in from the afternoon heat, the house feels like a cold kiss. It is a deliberate practice, a ritual I can commit to, something I do with attention and love. Opening, and closing, letting in, letting out, so that even though the house stands still it moves like a sea anemone in a tide pool.

I think about this when I encounter these doors that I closed to counter your openness. (And really, when I carry myself back and look again, you were closed plenty of the time, your contractions were stronger, in truth, because of your capacity to be open.) I practice opening my doors, just loving them open, however long they want to stay that way, opening them again and again and again. I talk to strangers in line at the grocery store. I drive down new roads just to see where they go. I stop at the thrift store when I don’t have time. I give away money. I love my husband even when, no, because he drives me crazy. On the other side of this door is imperfection. On the other side of this door is chaos. This door opens to a bottomless pit of despair. This door opens to ecstasy. I want you to know that I am opening the doors, letting it all flow in and out and in and out of this house, this beautiful house that is mine, wherever I am living.

0 notes

Text

I am doing my best

March 12, 2021

The ravens are playing with the dogs again this morning, leaning down from low branches, tilting their heads, winking, croaking, then swooping, swiftly, across the lawn. The dogs can’t get enough of this, chasing the ravens from tree to tree, eyes and ears trained upward, yelping from time to time when the excitement becomes too much to contain in their taut, expectant bodies. There they go, thundering past my window.

I’m always grateful when the ravens decide it will be amusing to tease the dogs, especially in spring, when no amount of tromping across the landscape seems to tire them out, at least not the young one.

Just when the men with excavators have come to lay a new water line to replace the one that was leaking in some unknown place (perhaps under a pond), just on that marvelous day, which we’ve been awaiting all winter, the line has begun to leak in a new undisclosed location.

I feel like I am being teased by ravens, but tortured is perhaps a better word.

How can something we rely on so heavily be so entirely inaccessible? For one, there isn’t a person on earth who can tell us precisely the path that the water line travels, across a half mile of steep rocky terrain before, outrageously, diving beneath the San Juan River. And then it is five feet underground. The leak is significant enough that we cannot ignore it, but not significant enough to allow it to be visible on the surface- the water just drains downward, soaking into the earth. And we do not own an excavator.

Last summer we redid the plumbing in the river cabin. I crawled underneath the house on my belly and elbows to run the new lines, tacking them to the underside of the floor between the joists, fitting them with tees, sending short sections up into the house through holes in the floor. For a time in August, Conor and I had to quarantine from one another, and I stayed in the cabin without water until I could connect all the fixtures and be sure there were no leaks. As I assembled the sink drains (the one in the kitchen needed to be snaked), hooked up the toilet, replaced the washing machine fitting three times before it stopped leaking, the conveniences of running water began to feel like an absurd booby trap I was setting for myself. So many places for things to break and flood, or drip slowly inside the wall and begin to grow mold.

How much complication we add to our lives for the sake of comfort, layers and layers of unseen infrastructure and technology that we do not understand. At what point do we begin to see diminishing returns?

Of course, the first hot shower I was able to take in the cabin washed away all of my yearning for a simpler way of living in a house. Well, for the first five minutes it did. Then it became clear that the mixer was faulty, giving me only very hot or very cold, but not warm water. I stood wet and naked and soapy outside the stream of water and cursed, and then prayed that I wouldn’t need to bust through the (freshly-patched) drywall again to fix it. Shortly after that, we began to get alerts from the water company that pointed to a leak in the supply line, so we turned the water off, and fixing the shower became a moot point.

In this whole ordeal with the leaking water line, my anxiety and frustration at feeling so helpless has occasionally landed on those who came before me. The ones who did have excavators and boring equipment and blasting equipment, the ones who looked at the river and the the steep rocky hillside and said, “Sure, let’s run a water line through there!”

I am jealous of their equipment and their skill and their optimistically reckless abandon. And I am angry at their lack of conservatism, angry that they couldn’t peer into the future and see me here with a leak in the line and no excavator. Couldn’t they have installed a few more valves? Couldn’t they, at the very least, have drawn me a map?

We brush hands with these past people frequently in our work. Sometimes we praise them for their ingenuity and sometimes we curse their lack of foresight. I try to think about those who will come after me. I try not to leave them any confounding mysteries to solve or disasters to fix, but I also know that I will probably fail. As I work, I whisper to these future ones and hope that they will find compassion for me: I am doing my best.

I am doing my best. I am closing and opening valves, monitoring water meters, listening to frost-free hydrants with a stethoscope. I have come to learn that my best is not born from a place of angst or overwhelm. It does not come through a gesture of strenuous striving. I cannot claim that I am doing my best when I am imagining worst-case scenarios or cursing those who came before me. I am at my best when I can hold a certain sense of lightness, of playfulness, a spaciousness that gives me room for creativity, room to try new things, to consider other perspectives.

At my best, I am the Sherlock Holmes of water leaks, I am playing a game with the ravens.

0 notes

Text

I want to build a temple

March 8, 2021

I want to build a temple for curiosity,

for slowness,

for listening,

for kinship with the animals,

and apprenticeship with the plants,

and reverence for the waters.

I want to build a temple for laughter,

for making art,

for books with paper pages, for poetry, read aloud at breakfast.

I want to build a temple for eyes to meet eyes without seeking power

or shame,

for long hours of breathing,

just breathing,

the ocean in the breath,

in the temple.

A temple for eating,

for chewing slowly,

for taking pleasure

in the flavor and texture and life in the food.

A temple for gratitude, and for awe, and for hope,

and for kindness.

A temple for touch.

I want to build a temple for simplicity,

for meeting basic needs and sharing the surplus,

in the form of time and energy and love.

A temple of enough-ness,

of fullness,

where there is joy in every sorrow and sorrow in every joy,

where everything is sacred and also

just an experiment.

prompt from Nadia Colburn and Rainer Maria Rilke’s first Sonnet to Orpheus

0 notes

Text

It does not reconcile

Last summer some guests were fishing in the river, at the big bend beyond the bridge, when they noticed beavers in the South Pond. I told them they must be mistaken, that they had likely seen muskrats, the smaller distant cousins of the beaver, but they were insistent. So I walked around the South Pond for the next few days with my binoculars, and there they were: two large swimming rodents, whiskered, dog-paddling along the warm scummy surface of the pond and then disappearing with a spectacular slap and splash of their wide flat tails. The dogs were beside themselves, and I was mystified. Early in the spring I had seen the fresh white points of alder and willow stumps chewed clean away, all up and down the river bank, but I couldn't find the beavers. And right under my nose they had been building a lodge in the pond, had been living alongside me all these months.

In the early fall, they relocated to one of the other ponds. For weeks I visited them daily, laughing as they took turns teasing the dogs. One beaver would allow Sugar and Mika to swim within a few yards before suddenly plunging underwater, leaving the dogs bewildered in the wake of a tail slap. Then the other one would surface at the far end of the pond, drawing the dogs in the other direction, and on and on until the dogs were too tired to continue. I inspected the banks of the pond and the sloping shores of its one island carefully in those weeks, puzzled. Where were they building a new lodge? Surely they were preparing for winter, but I couldn't see it.

It wasn't until November that I finally noticed how high the water had risen in the drainage area between the pond and the river. I walked along the reedy edge of the wetland, suddenly seeing the tooth-carved spikes of saplings poking up everywhere, and the great pyramid sculpture of sticks and mud, rising among the skeletons of cattails, and further along, at the narrowest part of the drainage, the dam, just knee-high, already beginning to freeze in the shadows of the willows.

I was astounded again. How had they done this without my seeing it, when I had been actively looking for it?

Standing at the edge of the dam, I could see how the beavers would expand their domain, could see how the spring rush of river water would turn this low grassy lawn into a wetland, enfolding the cottonwoods behind me in shin-deep flood water.

Conor went down on the next warm day with a pickaxe and spent several sweaty hours breaking the beavers' dam. It wasn't easy work. It took him all afternoon to carve a shallow notch in the dam, just enough to let a narrow stream of water through. He was amazed at the solidity of the structure. The beavers were excellent builders, and they had made a sturdy wall of mud and rocks and slender trees. It had taken them months of slow, steady work, methodical chewing, dragging, digging, weaving, with teeth and tiny claws. One branch at a time. One small scoop of earth at a time.

That night I dreamed of coyotes prowling and sniffing around the beaver lodge, and I woke up with a wave of dismay, a swirling nauseous shame, knowing that we had done the wrong thing. I could feel the brutish hacking force of the pickaxe in my own body, right in the center of my heart, and I could feel the draining of the water like the draining of the blood from my veins.

This feeling has not left me all winter. I visit with it almost daily when I walk by the beaver lodge, its entrance exposed where it ought to be underwater, the huge stockpile of winter food, built so carefully alongside the lodge, laid bare.

How quickly and how thoughtlessly we alter our environment, as humans. How little consideration we give to the power we have, and how to use it, and when. There are moments, I have to admit, when I pray for the swift decline of our species, pray that we will snuff ourselves out before we can do any more damage to this fragile and miraculous planet. And how do I reconcile these kinds of thoughts with my desire to bring another human life through my own body?

I don’t. It does not reconcile. One thing I know is that great creative power resides within the friction of contradiction. That embracing contradiction, without trying to reconcile it, is a more vulnerable, and more joyful, way to live.

Another thing I know is how relentless, how persistent, how resilient the impulse towards life is. How adaptive life is. If all of us humans did suddenly disappear, the earth would very quickly regenerate, rebalance, swallow up our roads and our buildings and our machines. When we all stopped moving last year, stopping flying and driving, stopped pushing and changing and extracting, there was, for me, a glimmer of possibility, of hope, that we might be capable of envisioning something different, a quieter way of being in this world. I had a very fragile precious sense that huge collective shifts in human behavior are indeed possible.

This winter, I learned about beavers, and I looked for ways that we might live alongside them. I found that sometimes people put a pipe through a beaver dam, with a valve on the downstream end, so that they can drain some water from the wetland when it rises too high, without draining all of it.

As the days stretch longer, as the snow and ice melt and the birds return and the trees wake up, I am watching the beaver lodge carefully for signs of life. I am hoping that I’ll begin to see beaver tracks in the mud, that fresh sticks will appear in the hole that Conor made in the dam. I am hoping that, while my attention is trained intently on this particular spot, the beavers might construct a whole new lodge in another entirely unexpected place. I am hoping that they will confound me once again.

I am praying for the grace of the resilience of the beaver. I am promising not to take it for granted.

0 notes

Text

“Write yourself a map back to yourself”

February 13, 2021

1. Set the oven in the main house to self-clean. You won’t realize it when you do it, but this will liberate you from spending the afternoon in there cleaning.

2. Take the dogs for a meandering walk in the woods as the snow starts to fall. Walk slowly. Notice the yarrow that has already germinated in the bare spots where the snow has melted. Don’t pay attention to where you are going. Be delighted when you find you have arrived at your favorite spot, where the oldest trees grow mossy in a deep rocky gully. Follow the elk tracks. Watch the snow collect on your hair. Enjoy the brief moment of disorientation when you emerge onto the gravel road again, sooner than you expected.

3. Go back to the main house and switch the laundry. Feel surprised by the thick layer of smoke hanging in the air because you set the oven to self-clean. Open the windows and turn on the fans even though it’s snowing. Hear the voices of children on the cross-breeze that will blow through here in summer.

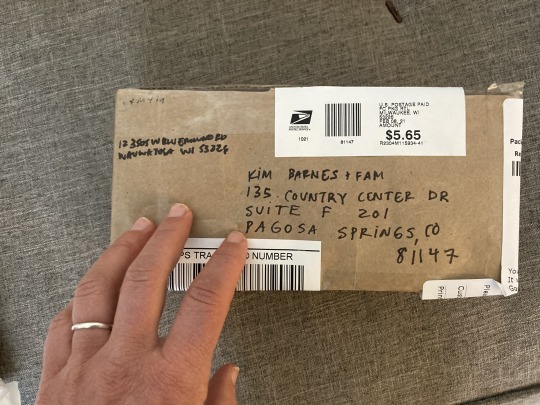

4. Put your little white dog in your little blue car and drive the wet roads to the UPS store. Hold the brown-paper parcel that your friend sent from Wisconsin. Examine her handwriting. Think about her hands, folding and taping the brown paper, writing your name in black marker. Imagine how her kitchen smelled as she did this. Savor the feeling of anticipation that rises up inside you.

5. Go into the grocery store. Allow yourself to be drawn in by the overflowing displays of Valentine’s Day flowers. Take your time looking at all of them. Give yourself permission to choose two slim bunches of understated flowers, some breathy filler greens and a few stems of stock in a soft romantic pink. Pick out some salad greens and some fancy cheese.

6. When you get home, answer the phone when your sister calls. Tell her how sweet it is to hear her voice. Listen to her laugh at Conor’s jokes. Think about the kringle she will bring with her when she comes to visit next month.

7. Boil water and make yourself a pot of tea in your yellow teapot. Sit down at your desk and write these instructions for yourself. Drink the tea slowly.

8. Walk back to the main house and enjoy the squeaky crunch your footsteps make in the wet snow. Close the windows. Sit in the living room and fold towels and watch the snow fall in the last light of the day.

9. Make a pot of rice, and while it cooks, prepare the ingredients for Lamb Rogan Josh. Sing along with Bonnie Raitt. Scoot around the kitchen in your socks. Save the lamb fat for the dogs’ dinner. Clean up after yourself as you go, lingering a little with the hot soapy water.

10. Take out your favorite vintage bowl. Look up a recipe for lady fingers. While you whisk the egg whites into soft peaks, think about how much you love sliding your hand under the warm wing of a broody hen when you reach beneath her for the eggs. Think about madeleines, and Paris, and perfume. While the lady fingers are baking, rub your favorite rose-scented cream onto your feet.

11. Eat the lamb. Eat it slowly. Let the spices warm your whole body. Sip a cold beer from a small glass.

12. Turn on the radio for the Grateful Dead Hour. Open another beer. Unpack the blue cashmere yarn that came in the mail today. Hold it in your hands and rub it against your face. Choose a pattern for the hat you will make with it. While you knit, think about the friend you are making the hat for. Think about her silver hair under the hat.

13. Place the package from Wisconsin on your altar. Resist the urge to open it. Think of how you will carefully slit the tape and unfold the paper tomorrow morning, in your bathrobe, with coffee and lady fingers. Think of the sweetness of opening a gift from your friend on her birthday. When you call her to say Happy Birthday, she will say Happy Valentine’s Day. After you get off the phone with her, you will call your grandmother to wish her a Happy Birthday too. You will sit on the porch in your robe and your slippers and watch the birds dance in the snow-covered trees while your grandmother tells you about her clever new recipes. She will make you laugh. You will feel grateful for the women who precede you. For now, though: place the package on the altar.

14. Climb into bed, with its two down quilts and freshly-washed sheets. Ask a question to your dreaming self. Tell Conor what was beautiful today. Let him make you laugh. Fall asleep while reading a book. Let the deep silence of snowfall embrace you. Listen to the strange and lovely answers from your dreaming self.

prompt from the Fierce Womxn Writing Podcast, February 9 episode with Sonya Renee Taylor

0 notes

Text

“Now I’ll stop pretending...”

February 11, 2021

Now I’ll stop pretending that I know what I’m doing or where I’m going.

It happens occasionally that for several days in a row there is a sense of movement, of forward direction, and then I am deposited again in this quiet empty place and I don’t know what’s next.

I keep asking the question, keep sitting at this table with a blank page and a pen, keep dropping into the deep well of my heart, inviting her to speak.

Sometimes she just says ‘Oh! How lovely to be here together!’

I pace around the room and think of my favorite poems and type them out on the typewriter, loud joyous clacking filling the silence for a few minutes.

I pour more hot water in my tea cup.

I tap my toes.

I tap on the walls, looking for a secret door.

I write without stopping in case something wants to come loose and hitch a ride on my pen.

I take out a fresh blank page.

I stare out the window.

Usually there is a moment when I wonder if I’ll ever have anything else to say ever again.

I am a tiny sailboat, far off shore, and the wind has gone slack.

There is a moment in every great adventure when you find yourself stranded in this way. The last bus has just left and there won’t be another until morning. The person you came to meet is a thousand miles away and won’t be back until next week. You went the wrong way on the highway and now you’re at the Canadian border.

The only thing to do in these moments is to delight in the unexpected time you get to spend with yourself. To rest in the impotence, let it soften your gaze, let it cradle you as you watch your sense of urgent purpose become useless.

Take the invitation to meet yourself in this moment, to know exactly where you are. Allow yourself to be surprised by what you do next.

prompt from writingfromthesoul.net

0 notes

Text

Spring Sacrament

February 10, 2021

We’ve begun to swing towards spring. There is a quickening that happens now, an acceleration in the lengthening of days, and I can feel a kind of restlessness under the surface of my awareness, a very slight sensation of being tugged at.

Soon I will pull the seed trays out of the barn and mix a big tub of soil and press the tiny miraculous seeds two-by-two into each little compartment. And then there will be sprouts, and tender true leaves, bright little baby tomatoes and eggplants and broccoli, all huddled together and reaching up and transforming.

Soon the river will swell, rushing and muddy, and the currants will burst forth with tiny green leaves, and the songbirds will suddenly multiply and the breeze will blow warm and cool at once, smelling like soft soil.

And still, there is snow in the forecast, snow covering the garden beds, and with every small whiff of spring that sends a tingle through my body, there is a firm and gentle hand on my arm, and the voice of winter, soft in my ear, “Not yet.”

It is reassuring, to rest a little longer here with winter, to savor the slowness, the simplicity, the quiet. To feel the arrival of spring from far-off, like a train rolling into the station, to feel that vibration rippling through me, but to do nothing about it quite yet. To stay right here until it is time, until the current of new growth and unfolding sweeps me up and carries me with it.

Transition is happening all the time, all year round, but this liminal space between winter and spring, so full of contradiction, is potent. To rest for a time with the sensation of pure potential, to hold it in the body, patiently, is a kind of sacrament.

0 notes

Text

Lifting the veil

February 7, 2021

continued from February 3+4

I began to think about what I would do. Leave the farm. Drive to Florida. Find a counselor, a yoga studio. I spoke these things to Lorena, and she listened.

And then she said, “What about your boyfriend? Haven’t you just fallen in love?”

She told me about her own father’s mental illness, her parents’ instability, and about the long road she had journeyed to find healthy boundaries, to build her own life, to claim that for herself.

“You’ve been here in California for a couple years, right?” she asked me.

I nodded.

“And do you love it?”

I nodded again, feeling my heart surge with my own wild and desperate love for California, her hills, her rivers, her trees. Her foggy mornings, the way she tinted green in February and turned golden in July. I loved the ocean here, how raucous and wild it was, loved how free I felt to be naked here. I loved the fertile overflowing sweetness of California.

“And how do you feel about Florida?”

The tears came then, my face crumpling, my body suddenly heavy and weak.

“I fucking hate Florida,” I managed to say, my words small and plaintive around the lump in my throat, my voice like a child’s.

It wasn’t Florida that I hated, it was the pavement and the strip malls and the cars and the people. What I hated was the willful obliviousness with which people lived in Florida. I hated the way I could hear Florida’s strangled, suffocated cries from under all that concrete and asphalt, could hear her crystal singing waters struggling to be free, and nobody else could.

“Well, here is an idea,” Lorena said, slowly, carefully, lovingly. “What if you brought your mother to California, instead? If you are going to support her, then you need support too. You need your friends, you need your boyfriend, you need to be in a place that feels good, feels alive, for you.”

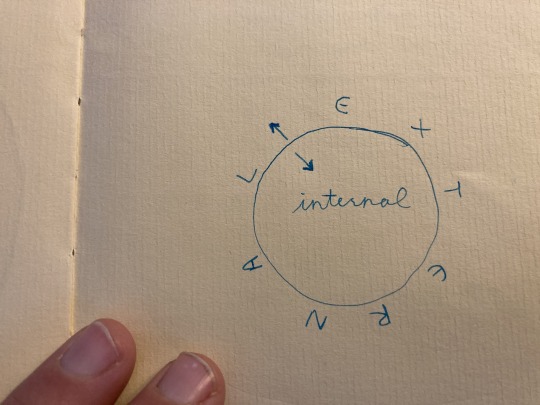

Years later, when I began to study the art of healing, I learned about the concept of veils. We each have a personal veil, a gauzy boundary layer, separating us from the external, filtering all the energy and information that comes towards us. The common gesture of a compassionate person, upon seeing the pain of another, is to lift the veil of the other person, to slip inside with them, to draw close to them in this way. To feel everything the other person is feeling inside their own body. The thing we would learn to do as healers was the inverse gesture: to lift our own veils and invite the other person inside, to maintain our own perspectives, our own relationship to our bodies, to the earth. To make contact with the other person and feel what was happening inside of them, not by making our own bodies into some kind of tuning fork, vibrating along with them, but by laying our hands on them, listening with our hands, witnessing, asking questions, and allowing our hands to speak back.

This moment with Lorena was, perhaps, my first glimpse of this idea, and it was, itself, a healing for me, a shift in perspective that changed everything. To give myself to my mother did not have to look the same as it always had. I did not have to change my life or give anything up, I did not have to make myself smaller, to crawl inside her life in order to love her.

I could stay right where I was, heart singing with the reckless abandon of my love for Marty and the wild aliveness of California. I could offer her a place in my life. I could invite her in. I could love her that way.

0 notes

Text

Pollyanna

February 6, 2021

I dreamed last night of another fire. It was, in the way of dreams, in Middletown, but also here, in Pagosa. My house was gone again. People’s belongings were floating down the river. Someone started collecting them and selling them on Facebook Marketplace. A woman moved into the main house, which hadn’t burned, and began advertising rooms for rent. “Wait a minute,” I said, “my house burned down. I’m responsible for this place, I need one of those rooms.” She was on the phone, and she waved me off, turning her back. Her children were on the floor, playing with toys they had rummaged from the credenza drawers. I called Rajat, who suddenly appeared in a suit and a trench coat, but he was already walking through the house with a contractor, discussing smoke damage. Wherever I turned, people were busy figuring out how to survive, how to keep going, how to gain a foothold in this new reality. Nobody was making room for me. If I wanted a place, I would have to start throwing elbows, there was no time to register this fresh loss, this new house-shaped pile of ashes.

Yesterday on my walk, I was thinking about how grateful I am for my “adverse experiences.” That’s how the words moved through my mind, in quotations, because I think about my mother’s mental illness, the divorces, the deaths, the fire, not as traumas but as teachers, things that have shaped me, given me access to a greater depth of feeling, a more complex understanding of what it is to be human.

But then Laura was talking about her sister, “the minimizer,” the one who moves so quickly to peace and acceptance when something terrible is happening. And I recognized this gesture she was describing, my own quickness to embrace tragedy, to move towards it with open arms and take it inside of me, to claim it as a gift, as a strength. When a herd of buffalo is charging at you, you stand and face them, you spread your magical cloak wide-open and sweep them up into it, otherwise they will trample you.

But in the necessary rush of this alchemy, this sorcery, this becoming-larger to contain the enormity of loss and change, what happens to the person you were yesterday? The one who fell asleep to the murmuring voices of her two parents under the same roof, the one who always planned to shop for wedding dresses with her mother, the one who had just finished building a new desk, which was now just ashes in the driveway? What happens to the one who is actually bewildered by this sudden sea change?

“Keep up,” you say to her. “Come, now, there isn’t really time for all these feelings.” Or maybe you don’t say anything to her at all, maybe you pretend she isn’t there, wandering around aimlessly inside the vast landscape of you, trying not to get run over by the buffalo. Sometimes she speaks to you in dreams.

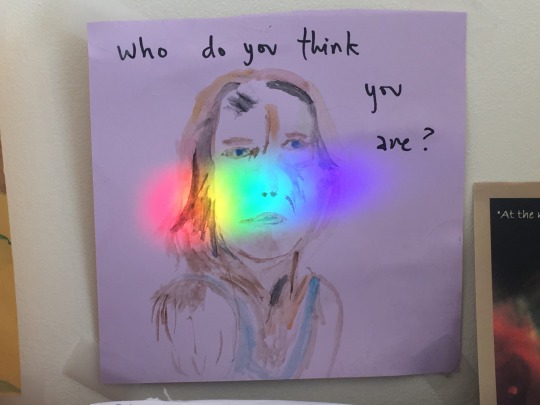

This morning I opened the curtains of my office windows and my prism showered rainbows across the ceiling and the walls. When I was ten I read Pollyanna, and was immediately smitten by her refrain: “There is something about everything that you can be glad about, if you keep hunting long enough to find it.” There was such power in her insistent choice to find what is good in the worst of things. Pollyanna hung prisms in the bedrooms of invalids, and I do too, in my way. I keep choosing to open myself to the whole of my experience, and to let the beauty buoy me along.

Of course, in our common vernacular, ‘Pollyanna’ has become a pejorative term. A ‘Pollyanna’ is excessively cheerful, glib, someone who sweeps complicated things under the rug. A minimizer.

And that is the danger, the pitfall of the magical cloak. You can forget to feel the difficult feelings. You can forget about the person you were yesterday, you can lose her, and if you do, eventually she will start throwing elbows.

The trick, it would seem, is to keep holding the hand of that part of yourself who is scared, or angry, or crippled with grief. Give her a room in the main house, close to the center of things. Give her a down quilt, bring her tea, sit with her while she cries. Hang a prism in her window. Don’t let her get lost.

0 notes

Text

Now or never at all

February 3 + 4, 2021

I stood at the outer edge of a crowd, everyone pressing forward, heads craning left and right, people standing on tip-toes, waiting for the parade of passengers, that outpouring of dislocated weary people, to begin. The fast-walking ones wearing headphones, the young couples struggling with strollers and too many bags, old ladies clutching purses. My mother, with a vacant glazed expression that immediately made me begin to cry.

Her face barely changed when she saw me, and even as I wrapped my arms around her, felt her soft cheek against my neck, slid my fingers into her hair and held the back of her head, she felt very far away. Once, I found a rabbit caught in the net of an electric sheep fence, and even after I had untangled her she laid there on the ground, frozen, her one eye empty and unblinking, shallow breaths barely detectable. That is how my mother felt, there in the middle of the crowded airport. Stunned.

We’d been planning this trip for months, but she had called me two weeks ago to tell me about the tumor that had appeared on her most recent scan. For two weeks I had been moving through my life in a kind of numb daze, a dumb haze, holding my mother’s cancer like a bomb inside me, very delicately, not wanting to touch it but also unable to put it down. I couldn’t think about it, couldn’t get my mind around it, I just wanted to see her. I worked, I ate, I slept, and all the while my heart beat out this steady aching call across the miles between us: mom, mom, mom mom. Ten more days, one more week, two more days, mom, mom, mom.

And now here she was in my arms, and there was nothing big enough or soft enough to comfort us both.

That night we slept together in the same bed, crisp white sheets, inside the bottomless silence of the San Francisco Zen Center. It felt like a cave, or a womb, or a great cathedral, hushed and holy, outside of time. I think she could have slept there for days. I woke up early and pressed my ear against her back, listening to her heartbeat, thinking about the cancer that was spreading in her body. I wanted to reach my hands inside her and make it stop.

She was like that all week, slow, absent, exhausted. It was raining, the farm cocooned in clouds like endless dusk, cold and damp. She spent most of the week curled up and shivering in my bed, under a pile of borrowed blankets, sometimes sitting up to eat a meal I brought, then burrowing down again. I was working, cold hands harvesting leeks, draining irrigation, herding cows down muddy lanes, packing winter squash into boxes. My mother emerged one afternoon, bundled in my insulated overalls and winter coat, and sat with me under the dripping shed roof sorting potatoes. She was strangely fixated on the dirt under her fingernails, concerned that her hands would be unkempt when she returned to massage school the next week. She stayed for about an hour and then went back to my bed.

On the weekend, we drove to Harbin, where Marty had arranged for guest passes and set up a tent for us. I could see how hard she was trying to stay present, engaged with him, how much effort it took to smile, to make eye contact, to be in conversation. At the pools she got dizzy, light-headed, she slipped on the stairs and I caught her naked body in my arms, her skin hot and wet. She was so heavy.

We drove to Santa Rosa to stay with Lorena, an old friend of my mother’s from New Hampshire, who she hadn’t seen in years. When we got out of the car in her driveway, her house an island in a sea of vineyards, Lorena came out and embraced me, exclaiming “My God, you look amazing! You haven’t changed a bit!” And then over my shoulder, she saw my mother, and, pulling back, I could see in her face how much my mother had, indeed, changed. The years of medication had made her puffy, and the skin under her arms hung loose, and there was a long jagged scar across her nose and forehead where she’d had some cancer removed last year, an ordeal that had ultimately landed her in a psychiatric hospital.

That night, my mother spiked a fever, sweating through two nightgowns and Lorena’s purple sheets. We drove to the urgent care the next day, and a young doctor diagnosed her with a urinary tract infection. She was dehydrated, too, and while my mother slept in a dim room in the clinic, an IV slowly dripping fluids into her bloodstream, Lorena and I walked across the strip mall plaza to get some food.

“She’s really not well,” she said, “she’s going to need some help.”

In that moment, I relented and allowed myself to know the truth I had been holding at bay since the phone call, all through the two long weeks I’d been waiting for my mother to arrive, and all through this past week, from the moment I’d first seen her at the airport. My mother might not live through this. She might only have another year or two. And what followed from this knowing was another: I needed to be with her.

In the past six years since she had upended her stable life, blown up her marriage, gone off her medication, I had reluctantly, cautiously, offered my support. From a safe distance, on the phone from Connecticut to New Hampshire, I had listened to her struggles- the various men she had met online and fallen in love with, how the power was out because she hadn’t paid her bill, her roommate’s obnoxious children, the endless yard sale she had set up in the garage to raise a little cash.

Then there was the spot on her leg that her doctor had noticed. The biopsy results. I went to be with her for the surgery. I helped her pack up the house, took money from my IRA to pay for the movers, drove with her and the dog to Florida. I helped her find an apartment, find doctors, get a library card, figure out how to buy a beach parking pass. I stayed for nearly a month, helping her establish a rhythm, soothing her sudden bouts of fear, watching sunsets at the beach, until I had to go back and start sowing seeds.

I did all of those things, but the thought of truly entwining my life with hers, becoming responsible for her, made my heart surge with panic. I kept the door to my heart partly closed, and I kept my hand on the knob. Eventually I had even moved three thousand miles away from her, packing all of my love and worry for her into its own small room, which I mostly tried to keep closed.

And now I knew that I had come to the end of that road. Now I had to let her in, marry my life to hers, whatever was left of it. I had to give myself to her, because it was now or never at all. Our time together, in bodies on this earth, was short.

0 notes

Text

You have to lose what is temporary

February 2, 2021

The only objects that emerged from the ashes of my house- and not whole objects, either, only pieces, only fragments- were my mother’s dishes. Dishes she had selected, dishes she had used, dishes she had touched. We had packed them together, into boxes in New Hampshire, and again, in Florida. We had unpacked them together, too, in California, and used them in those last months, for birthday cakes, pancakes, tapioca pudding, beet sandwiches.

In the nearly three years since her death, I had used my mother’s dishes myself, used them daily, for eating, for nourishing the body she gave me. I used them, also, for keeping her close to me. My daily mundane tasks of washing them, drying them, stacking them in the cabinet, became a daily mundane conversation with my mother. A conversation like the kind we used to have over the phone line, in the late mornings, in our bathrobes, long and meandering, sharing the unremarkable unfolding of our lives. Doing laundry, weeding the garden, sorting through clutter in the basement.

And now here were my mother’s dishes in the place where my kitchen once stood, broken, blackened, glazes crackled into mosaic, so familiar and so completely changed. The ash was fluffy, powdery, fine, as I reached in again and again, feeling for the hardness of baked clay, pulling the pieces out and holding them one by one in my hands.

I collected a sizeable pile, and I thought about the art I might make with them. But then the thought of packing them into a box to carry away with me made me feel so heavy that I could not even lift my hands. So I just sat there on the ground next to them, knowing they would stay there. They would stay there, and I would go. The invitation from the fire was to leave everything behind, let everything go, and discover, in the act of moving forward, exactly what I carried within.

Years later, just as my sister was graduating from college and moving far away from home for the first time, her mother became ill. I sat with her mother at the graduation, and I was shocked by her frailty, how it felt like she was all the way at the very end of a long tunnel, and I could barely see her.

I wanted so badly to hold my sister that summer, to speak to her from the other side of death, to tell her that I did not find it strange or wrong to want to be far away from a mother you have always mothered, to want, in some small powerful way, to annihilate her, and at the same time to feel that her death might be your own annihilation.

My sister retreated from me. The stronger my longing to sweep her up in my embrace, to let my heart talk to hers, the deeper she withdrew.

I have come to learn this about her, my little Cancer hermit crab sister, I have learned how to slip that shell into my pocket and carry her without poking at her. I have learned that she will emerge in her own time.

But that first summer was hard for me. I hardly knew her, but I also somehow knew her deeply, and the relationship we shared was my most precious treasure. It was a sacred, surprising, tender gift, an unfathomable grace. I had emerged from this long season of loss to find that I had a sister, and it was terrifying to think I might have misstepped, misunderstood her, misheard her, poured out too much of my own story, leaving no room for hers. I had missed her birthday. It was terrifying to think I might have lost her.

I went to the little antique shop in town, which was full to the brim with shelves and shelves and nearly toppling stacks of my mother’s dishes. Fiesta-ware, Franciscan-ware, Stengl, Yellow-ware, McCoy. I chose a bowl like one of hers, white with pink and blue stripes, wide and deep. I packed it carefully and sent it with a letter to my sister, to her new apartment in Denver. I wrote about my mother’s bowls, how it was a comfort to me, after her death, to pull one out and use it for baking. I wrote about how the bowls had burned in the fire. I wrote about how, eventually, I had bought a few bowls like hers, how even though my mother had never used this particular bowl, it was still a way for me to call her up, to touch something that remained unchanged, unbroken. How the fact that the bowl had not actually been hers almost made the ritual more potent, the gift of the fire returning again and again: You have to lose what is temporary- the house, the body, the dishes- to know what is eternal.

The next spring, visiting my sister in Denver, I looked for the bowl. While she was sleeping, I tiptoed around in her kitchen, opening cupboards. Eventually I found it, broken in a hundred pieces. It had arrived like that, she told me later. A perfect poetry I could not have written if I tried. She spent a long afternoon with superglue, piecing it together, and now it sits on her kitchen counter, holding fruit. Now, she visits me, and we make birthday cakes in the bowls which never belonged to my mother.

0 notes

Text

Absence, fonder, thanks Marty

February 1, 2021

Conor left today. He’ll be gone for five days. I found myself drinking him in more deliberately this morning. His skin against my skin, warm in bed, the contours of his face, the way he gripped the spoon at breakfast. His scent, and the soft brush of his beard against my cheek, my chin, when he kissed me. The sparkle and the crinkle of his eyes. The way his feet turn outwards as he walks.

Sometimes I call up Marty, the sound of his laugh, the way he tried and failed to hide his teeth when he smiled, tilting his head down and away. His hairline. His hands. It is sweet, to make contact with his essence through these small but potently remembered details.

Marty has had much to say to me over the years since his death. These days, it is this: when I do this, when I call up all the things I can remember about Marty’s presence, once I have greeted him, said hello, I feel an urgent need to go and find Conor, to touch him, look at him, really feel his aliveness. Look! He is here, alive and embodied, with me! How miraculous. How easy to forget.

Sometimes I watch Conor brushing his teeth or folding laundry and I can see him as an old man, skin wrinkled and sagging and spotted, hair thin and grey. It fills me with a humble joyful gratitude, so delicious I want to squeal. I want to open my arms and throw my head back and sing praise. How lucky I am.

It will be sweet to appreciate him through his absence in these coming days, to become more aware of him because of all the small unconscious ways in which I expect to find him, and then don’t.

It will be sweeter still to see his face again in front of me.

0 notes

Text

“...which is another name for God...”

January 31, 2021

Once a decision had been made, once there was a plan, a particular Saturday afternoon in July when Mike would pack all his belongings and leave, I decided I could not be there to watch it. I did not want to feel like I was being left, because that was not what was happening at all. No, we were both leaving, leaving the thing between us which we had been wrestling for nearly five years, tenderly laying it down, backing slowly away, a last loving gaze between us breaking as we turned from each other, heading in separate directions.

I needed someplace to go, so that I could feel how I was setting out, on my own. I drove the long Covelo road, hugging its snake-like curves, flashing in and out of oaks, brown grass stretching across waves of hills like bodies stretched on their sides against the earth. The Eel River, coursing alongside me all the way, disappearing far below me, then reappearing again like a faithful companion. I drove south on the 101, bought cigarettes in Willits, and then turned east on the 20, past Lake Mendocino, and the small triplet Blue Lakes. I had driven this route once before, in June, to attend a gathering of Biodynamic farmers, hosted by a small intentional community, which was perched on the lower slope of Mount Konocti, a volcano, with the flat expanse of Clear Lake at her feet. It was there, among softer-bellied people than the Decaters, that Mike felt a spark of desire. And it was there, late at night, lying in the grass between the grape vines, looking not at each other but up at the stars, that we finally spoke what we had each been carrying in our hearts, all the way through the long journey from Connecticut to California. Through the mountains of Pennsylvania, into the heart of Chicago. Through the corn-stubbled plains of Oklahoma, through the painted desert, the Grand Canyon, through the salt flats of Death Valley, all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

The thing I had known since an icy morning in January, the thing that appeared suddenly, fully formed and solid, a crystal of knowing, of truth: we could not stay together and grow in the ways we each needed to. I would walk away from this.

I had held that knowing all these months, waiting for the moment when it would light up and move out of my mouth of its own accord, terrifying but necessary, birthed through words I would not know until I had spoken them. So yes, it was there, with the grapes and the grass and Mount Konocti and the stars overhead and the shimmering lake below us. It was there that I spoke the truth, there where I reached out with both hands and pulled my own life towards me, felt the simultaneous thrill of relief and the rippling rush of sorrow, both washing through me like a late summer rain, warm and unrelenting and leaving me clean, sparkling, empty.

It was there that Mike was going now, so perhaps it is strange that I chose to drive right past it, this time on the south side of the volcano. But when I did, I sent my thanks, a tiny bird fluttering out from my heart, carrying a prayer for Mike, that this place would hold him well, would be kind to him.

As I drove, I smoked cigarette after cigarette and listened to Lauryn Hill at full volume. I called and left wild messages for a dozen friends who I hadn’t talked to in months. I felt untethered, in a way that changed from moment to moment, from joyful exhilarated glorious stretching freedom to a terrifying sense of being lost, careening out of control. I cried, letting deep wailing sobs shake my body and pour out of my mouth, vision blurring with tears, and then clearing again, my hands gripping the steering wheel, steering myself into this unknown future.

I was alone with myself.

When I arrived at Harbin after two hours of hurtling along highways, the stillness there was startling. I could feel my inertia, the speed at which I wanted to keep moving, flying, forward, away, moving. But here I was entering this kind of hushed temple, everything slow, silent, watery. Being alone with myself here was uncomfortable. It was uncomfortable to get naked in front of strangers and stand neck-deep in warm water, breasts floating to the surface, exposed in the sun. The roots of the bay laurel running under my tent were uncomfortable. The long hours of wandering alone after soaking, not knowing what to do with my hands, not wanting to see anyone or be seen by anyone, not wanting to think about anything, were uncomfortable. I struggled to get away from myself, but there I was, in every direction I turned.

I left early, packing up my tent with a kind of searing panic, and when I got back in my car it was a relief to be moving again.

I had seen a sign on the drive to Harbin, marking a northbound road off the 20, towards Lake Pillsbury. I remembered seeing signs for Lake Pillsbury at the far southeastern edge of Covelo. So when I saw the road on my way back, I turned onto it without thinking. If I could get to Lake Pillsbury from here, and I could get to Lake Pillsbury from Covelo, then I could get from here to Covelo. I felt a lightness move through me at this change of course, as if I’d been lost and had suddenly found the path again.

I arrived at the lake and, seeing no more signs, I stopped at the general store, with its squeaky screen door and wide wood floor planks, canned goods and fishing rods and two men behind the counter, smiling at me like uncles. They didn’t know how to get to Covelo, but here was a map of the Mendocino National Forest, did I have a spare tire, a flashlight, bear spray, a radio? I had none of these things, and the map was incomprehensible.

I thanked them and got back in my car and drove aimlessly, frustrated, hot tears on my cheeks. It seemed foolish to proceed, when the shadows were already beginning to lengthen. But I didn’t want to go back. To retrace my steps, to return to the familiar route, felt like giving up something hard-earned, something I desperately wanted to claim as my own. I pulled over by a small stream and took off my dress, laid my naked body in the cold water. Fuck it. I would keep going.

The forest was vast, the roads narrow and rutted and barely marked, and they went on and on forever. I was miles away from anything, from anybody. I reached a dead end, no room even to turn around, I had to back down an incline, pine branches scraping the sides of my car. Have I completely lost my mind? Am I totally insane? I kept asking the question out loud to myself, and I kept hearing my own answer: Even if I was stranding myself out here, I wasn’t alone. I was with myself. And there was a way through. This was the way. Keep going.

When I finally emerged from the forest and onto a paved road, there was the round valley of Covelo stretched out below me, and above it, a full moon, glowing soft and bright in a pink sky. I stopped the car and got out, feeling the warm evening air, thick with the scent of pine. The engine ticked. Crickets chirped. I stood and breathed in that stillness, and tilted my head back and let the moon talk to my open heart: You found your way, your own way home, and look how beautiful it is, look how this valley is laid out to receive you, to embrace you. Look how the road unfolds itself before you. Look how you are on your own, but not- not ever- alone.

0 notes

Text

Supernova

January 30, 2021

During that entire trip, while I was visiting one old friend after another, driving familiar roads, while I was packing all of my belongings up in Mike’s house and moving the boxes into my dad’s garage, while I was knitting a hat for the man I had been seeing in California, I was in touch with my mother, in Florida, where I would fly after my time in the northeast.

That visit to my mother was like the distant rumble of a train, and I was tied to the tracks. She had been, for the past several weeks, on a manic high. When she was manic, she burned like a hot sun, and the heat pulled people toward her, the heat kindled a flame in them, woke them up, made them feel alive. But I was already too close to her, and leaning in to her made me feel like I would be incinerated, swallowed up and burned clean. So I retreated from her when she was like that, wild-eyed and laughing and chasing her ideas like rabbits. I withdrew into the still quiet darkness of my own self, I drew the curtains closed and waited, listening for the moment when she would burn herself out, a supernova, and then collapse back into herself, the inevitable black hole.

For years I could do that because she was not alone. She could always return to the stable platform that Chip provided, the lifeline that he always extended. And for years, too, she was medicated, swaddled in a dullness, floating along dutifully on an even keel, her world muted and muffled.

But now she was precariously on her own without a safety net, and I was living thousands of miles away. During this manic high, her flame had drawn in a moth, a man named Carlos, and together they had been writing bad checks, the neighbor had called the cops during a screaming, glass-shattering fight in the middle of the night, her landlord had kicked her out. I remember the phone calls, how fast she was talking, how confusing and convoluted her explanations were, how I just wanted to hang up and pretend she wasn’t my mother, pretend she was just some ranting lunatic on the street. I wanted to push her into a tiny room in my mind and vacuum seal it shut.

But I couldn’t do that. I only had one mother and I needed her. I had to walk straight into those flames.

0 notes

Text

‘Back east’

The writings that were coming through me in the first couple weeks of this experiment felt discrete, whole, complete, like glistening pebbles emerging from silt in my palm. In the past few days, it has felt like I am reaching for something bigger, excavating a larger story which I can’t yet see, whose form feels mysterious. I haven’t wanted to post what’s been showing up because it feels open-ended, unfinished, asking more questions than it answers. It feels muddy. My mind keeps intruding on the writing process, judging, trying to insert a narrative structure, which makes the writing feel jagged. But I think I will keep sharing, even though it is uncomfortable, because my commitment is to being visible, and to not-knowing, and to being visible in my not-knowing. My commitment is to keep the current of creativity flowing by allowing my writing to be read, even if it is unfinished, even if I don’t know what is trying to be communicated.

January 29, 2021

When I move inside this morning to meet myself on the wide open plain of presence, the wind blowing through is sorrow, and the sky overhead is cracking with cold heartbreak. It’s like a dream fragment- I have to stand very still and not look directly at these things, or they disappear.

My first winter at the farm, I went back east for several weeks. ‘Back east’ is the way it’s always said in California, as if the east coast is some kind of time capsule, as if returning there means going backwards. Back east, out west, this American delusion of some endless frontier, a happiness that rides the horizon, always ahead of the sun. ‘Back east’ became a part of my view of things, it infiltrated my own language. I did not refer to the east coast as ‘home.’ I did not have a home. There was no place I could drive to late at night without calling ahead, no place whose driveway, porch lights, squeak of door hinges would give me permission to uncoil myself and become soft. What I carried was an aching longing, a pulsing beacon that searched but did not find an answer.

My first stop on that trip was Chicago, where Chip was living with his new partner in a luxury high-rise apartment overlooking Lake Michigan. I remember staring out at the lake late at night and feeling how strange all this glass and steel and concrete was, clustered at the edge of this living body. How inert and immovable the city was, layers and layers of solid boxes laid in grids where there should have been grasses. I was looking out that window when I spoke with my father on the phone, feeling the space stretching between us, him in Boston, me here in this unfamiliar city, made stranger by the way I could feel that lake like an old friend, could feel a nostalgia for a time when the prairie rippled out in all directions, flat, silent, dark, deep. My father’s voice was small, strained and sad as he apologized, it was like one continuous swallowing apology. I could not stay with him in his home, he said, it was his fault, he said, he was so sorry, he said, but he would find me a hotel room.

And so, a few days later I found myself in a Panera in a Boston suburb, eating soup with my half-siblings at a big round table. All around us was clattering noise, chairs scraping, children shouting, everyone’s big winter coats and wet mittens pressing against us. But here were Katherine and Matthew, astonishingly, teenagers, whole people. When had this happened? In my mind they were stuck as small children, shy, awkward, responding to my grasping questions with one-word answers. But now they had car keys and gym bags and text books and cell phones, now they were leaning in across the table and telling me about the uncomfortable scene in their house a few days before, telling me how things were with their mom and their dad. As they talked about their dad, I felt a sudden surge of joy, because the man they were describing with so much love and tenderness, this man whose sense of failure they wanted to comfort, I recognized him. He was my dad. He was our dad, the very same man, Ham Barnes, and for the first time in my life I was not alone in loving him. Here was an unexpected revelation, a surprise answer to my homing beacon, this solid tripod of love for our father who was there at the table in all three of our faces.

0 notes

Text

How much time it took

January 25,2021

Today is turning out to be the kind of day where I just want to sit and watch the world exist, watch it move past me.

There is nothing in particular I want to write about. No food I am wanting to cook. The clean laundry can stay in the basket and the dirty underwear can stay on the floor. I scan through my list of things to do and nothing jumps out to volunteer.

Snow falls off the roof in sheets. The sky is briefly blue and then another low white blanket of cloud slips in overhead.

I talk to an old friend and neither of us has too much to say, but we both remark on the way things form in their own time, the way a dream can rumble in the void, like a shimmering wild beast cavorting in the darkness, for years it is untouchable, barely visible. And then one day you wake up and you are living inside of it. Your wild dream has become this everyday object, like the spatula you use to flip the eggs.

So days like this have their place. It takes a lot of flat and unremarkable days, laid end to end, before the bigger movements, the grander gestures of this life become visible. If my hands are idle on a day like today, perhaps it is because some other part of me is out rounding up feral horses in a vast cosmic desert.

The snow has blown in now and the view out the window is white, a blank page. I am sitting in this little cabin, whose every detail I have labored over. I have touched every inch of the walls, the floors, every crack and seam. It is an island, an oasis in this sudden whiteness. It feels right just to sit here inside of it, feeling how much time it took, how much idle time it took, to make it real.

0 notes