Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

"My mother's death was an irreparable loss to us all and left a great gap in our lives. She had, indeed, been the mistress of the house, a wise and loving wife and mother, whom we respected as much as we loved her... My childhood ended with her death, for I became the eldest and most responsible of her orphaned children".

Recollections, The Memoirs of Victoria Milford Haven

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Alice had many talents of her own that she did not rate highly enough. She was beautiful dancer, a graceful skater, an accomplished horsewoman, the only one of the sisters with a real flair for clothes. Her first sight of a crinoline—worn by the Empress Eugénie at Windsor in April 1855—was a revelation; in a flash she recognised the magical effect of simplicity in an age of frills and flounces. She loved music and played the piano well, drew competently and had a gift for acting. Miss Hildyard, who stage- managed their plays and tableaux vivants, gave her the most difficult parts as a matter of course.

More than the others, Alice was deeply conscious of her position as a member of a ruling family—not that she wanted to demand homage but because she had to make herself face up to her responsibilities. This sometimes meant that she demanded too high a standard from herself, but it did not make her rigid, for she was addicted to ‘pranks and larks’ even at the expense of rank and dignity, and the household always turned a blind eye when she slipped into St George’s Chapel in ordinary clothes and sat at the back rubbing shoulders with her mother’s subjects. It was innocent enough fun and the natural result of having young parents and unconventional holidays, but it gave her a feeling of escape which was important to her. Lord Clarendon’s daughter Constance wrote that she was “just like a bird in a cage beating its wings against the bars and if she could get out wouldn’t she go it?” This is what Alice herself believed. It was only as she grew older that she began to realise that the barriers she imagined round her were not those of rank but consisted of more mundane things like lack of purpose and appreciation, intellectual barrenness and poverty. Sadly, she was to labour in a soil that was unreceptive of the seed she tried to sow."

— From the book "Queen Victoria's Children", by Daphne Bennett.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Pauline of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Hereditary Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Hermine of Schaumburg-Lippe

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Archdukes had arrived in Naples, aboard the Elisabetta, on January 30 [of 1859], and immediately went to greet the reigning family of Tuscany, who had arrived there on the 22nd, taking lodgings at the Foresteria, to attend the wedding celebrations [of Prince Francesco of the Two Sicilies and Duchess Marie Sophie in Bavaria], despite the anxiety in which they lived due to the illness of the young Archduchess Anna [née Princess of Saxony], wife of the Crown Prince Ferdinand. The Grand Ducal family was almost complete. In addition to the Grand Duke Leopoldo, the Grand Duchess Maria Antonia, sister of the King [Ferdinando II of the Two Sicilies], the hereditary Archduke and Archduchess, Archduke Carlo and Archduchess Maria Luisa, the last of the six children of Leopold II, there was a numerous retinue [sic Carlo and Maria Luisa had two younger brothers]. Archduchess Anna, 23 years old, younger sister of the Duchess of Genoa, who had fallen ill in Florence, was treated by the Florentine doctors Capecchi and Del Punta. The Grand Duke had asked the King for a good Neapolitan doctor, and the King had sent Don Franco Rosati to Florence, in whom he placed much greater trust than in Ramaglia. Under Rosati's care, the princess seemed cured; but when the Grand Ducal family came to Naples, the illness reappeared and soon degenerated into tuberculosis. Rosati, who lived in the same palace of the Foresteria, also treated her in Naples, and Del Punta was also called from Florence, who arrived only in time to sign the last bulletins with Rosati. She died on February 10; and, struck by such a grave misfortune, the family no longer had the courage to remain in Naples, and so, two days after her death, they had the body of the poor Archduchess transported to Florence, where she was buried in San Lorenzo, the grieving family left on the morning of February 21, embarking for Livorno. The Neapolitans were amazed by the simplicity of the Tuscan Court. (...) A long journey from Florence to Naples, a serious domestic misfortune and a melancholy return, without seeing the Sovereigns, nor the spouses, deeply moved the souls of the Neapolitans.

de Cesare, Raffaele (1900). La fine di un regno (Napoli e Sicilia). Parte I Regno di Ferdinando II (machine translation, keep in my mind that nuances may/have been lost)

Pictured: Anna, Hereditary Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Archduchess of Austria, by Philipp-Albert Gliemann, unknown date (Via Wikimedia Commons).

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Count of Trani is the nicest and his wife very pretty and showy-looking though not a real beauty. She must be very like her sister the Empress of Austria — though of course not to be compared to her in beauty".

Crown Princess Victoria of Prussia to Queen Victoria

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna of Russia, Hereditary Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, by Kreutzinger.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Alexandra Iosifovna of Russia by Hau.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

“At 7 in the morning, the first signs of premature birth occurred.

At 8 o'clock the distinguished young woman [Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna] took Holy Communion according to the rite of the Greek Church. Her confessor had demanded to see her, and so the Grand Duchess' desire for the ordinance was brought about in a natural way. According to the custom of the Greek religion, the sick woman asked not only her parents present but also her husband's forgiveness for any slights. This was so touching for the young gentleman, who was not used to this ecclesiastical form, that he knelt by the bed and also asked for forgiveness for any worries that he had caused her during the short time of their marriage.

An hour later she gave birth almost painlessly and unusually easily to a boy who screamed loudly and audibly, although he was only 25 weeks old. I went with the child and all members of the august family, except her father and mother, into the next room, where I wrapped him in warm cotton wool to await the baptism. All the members gradually approached the basket to see their sister's child . The prince [Friedrich Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel] also approached and seemed deeply touched with fatherly joy, which dwindled with each passing moment.”

A Protestant priest had been sent to perform the baptism. However, when he had not arrived after three quarters of an hour, and the weak spark of life threatened to go out at any moment, the fear arose in the entire circle of those present that the child might die without the sacrament of baptism. Someone, I think it was the Duke of Leuchtenberg, had opened the door of the sick room and saw the emperor kneeling beside the bed. No one dared to disturb this moment, and yet danger was imminent.

I handed over the care of the young prince to a very capable chambermaid, entered the mother's room and actually saw the emperor [Nicholas I] at her bedside, holding both of her hands in his in a half-kneeling position.

To get his attention I made a small noise, but he would not look up, and I was forced to wave. He immediately got up, came toward me, led me to the doorway and asked,

“What do you want?”

“The child is in danger of dying any minute; the clergyman has not come. Does Your Majesty wish to baptize your grandson yourself, lest he die without the ordinance?”

“Yes, yes. Certainly.”

The emperor immediately went into the next room and entered the circle of his family surrounding the basket with the child. When the bowl of water was given to him as ordered, he performed the baptism with a dignity and emotion that made the deepest impression on me. Everyone knelt around the great emperor, who was baptizing his youngest grandchild. Then, without another word, he left the room and returned to his daughter’s bedside.

After a good half hour the summoned clergyman finally appeared in full regalia, decorated with several medals. The child was barely alive; but he performed the baptism according to the regulations of the Protestant church.

Of these two baptisms, that of the grandfather of his grandson was certainly recorded in heaven.”

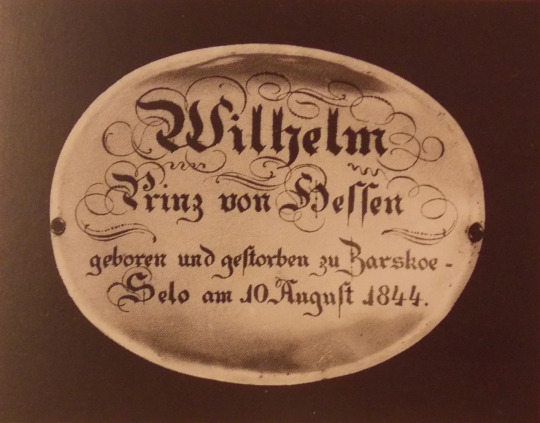

— Imperial physician Dr. Martin von Mandt on the premature birth of Prince Wilhelm of Hesse-Kassel, the short-lived son of Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna of Russia.”

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On October 26th, 1944, Princess Beatrice died in her sleep at the age of 87. She was the youngest and last surviving child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and at the time of her death the current Queen, Elizabeth II, was 18 years old.

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Whenever I see the Empress among the public, I have the impression that she is immeasurably far away in soul, that she has nothing in common with this motley secular crowd that gathers around her. Her sisters-in-law, Grand Duchesses Maria Nikolaevna, Olga Nikolaevna and Alexandra Iosifovna, make a completely different impression. They shine with beauty, their facial features are more regular than those of the Empress, their posture is perhaps more regal, but the Empress has much more charm, a charm that comes from the soul and is difficult to define, but making one’s innermost soul-strings sound.”

- Anna Tyutcheva on Empress Maria Alexandrovna of Russia.

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

“During these early days of my life in St. Petersburg, I was introduced to Grand Duchesses Elizabeth and Anna, the wives of Alexander and Konstantin. The first, a former Princess of Baden, was lovely and kind, and at the same time possessed the most gentle character. The latter was probably even more a striking beauty, but still she could not overshadow the charms of Elizabeth.”

- Prince Eugen of Wurttemberg on Grand Duchesses Elizaveta Alexeievna and Anna Feodorovna, wives of the future Emperor Alexander I of Russia and his brother, Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The fashionable British artist painted in turn the whole imperial family in full length […]. Of the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, who was then fully forty years old, the flattering brush of the British woman made a twenty-year-old beauty; but it was very difficult for her to flatter the grand duchesses… here nature herself could compete with the artistic ideal.”

- M.D. Buturlin on Christina Robertson’s portraits of the wife and daughters of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia.

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Princess Clothilde of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Archduchess of Austria

17 notes

·

View notes