Text

the way cassowary babies don’t instinctually know how to eat and have to be shown to peck at and swallow fruits :’-) the time the male spends with them as a single parent is unusually long too, over nine months, and we think it’s because they eat such a wide variety of rainforest fruits and seeds that they need to be taught which ones are poisonous. they look like this

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Osmia orientalis is apparently a bee that will use a old snail shell as a nursery c:

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i hope this is alright to ask but i was wondering if you had any reading recommendations about invasive species and their management/control/rhetoric. there just seems to be a lot to it. thank you!

Woah. Look at this post I was drafting literally two hours before you sent this, about the nationalist appropriation of rhetoric of "native vs. invasive" species in Hungarian land management:

Appropriate case study: (1) The tree was non-native and its introduction was facilitated by Austro-Hungarian imperial aristocracy and military, especially as fortification during wars in the eighteenth century. (2) It out-competed native trees and the government encouraged plantations of the species. (3) Because of its economic and political importance, the reactionary Hungarian parliament in 2014 officially named the tree "Hungaricum" (native/national heritage).

Yes, there is a lot. This is practically a whole discipline.

If you're looking for a collection, anthology, or singular book with multiple tangents, angles, or perspectives (rather than having to search through individual articles or journals), there are three collections I'm recommending below, but this also might be helpful:

Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene, co-edited by Anna Tsing (she's probably the most high-profile scholar of this subject). Aside from containing a bunch of freely-available essays from about 100 authors on altered ecologies and rhetoric/imaginaries of environments in the Anthropocene, their big online portal just published the entire syllabus with a bunch of maps and graphics and free articles, in formats for non-academic reading groups, undergrad classes, and graduate seminars. If you go to Feral Atlas's homepage, you'll see a straightforward list of all of those authors.

---

The Ethics and Rhetoric of Invasion Ecology (Edited by Jame Stanescu and Kevin Cummings, 2016). Including chapters:

"Alien Ecology, Or, How to Make Ontological Pluralism" (James K. Stanescu)

"Guests, Pests, or Terr0rists? Speciesed Ethics and the Colonial Intelligibility of "Invasive" Others" (Rebekah Sinclair and Anna Pringle)

"Spectacles of Belonging: (Un)documenting Citizenship in a Multispecies World" (Banu Subramaniam)

---

Rethinking Invasion Ecologies from the Environmental Humanities (Edited by Jodi Frawley and Iain McCalman, 2014). Including chapters:

"Fragments for a Postcolonial Critique of the Anthropocene: Invasion Biology and Environmental Security" (Gilbert Caluya)

"Experiments in the Rangelands: white bodies and native invaders" (Cameron Muir)

"Prickly Pears and Martian Weeds: Ecological Invasion Narratives in the History and Fiction" (Christina Alt)

"Invasion ontologies: venom, visibility and the imagined histories of arthropods" (Peter Hobbins)

---

The Invasive Other special issue of Social Research, Vol. 84, No. 1, Spring 2017. Including articles:

"Introduction [to Social element]: The Dark Logic of Invasive Others" (Ann Laura Stoler)

"The Politics of Pests: Immigration and the Invasive Others" (Bridget Anderson)

"Invasive Others: Toward a Contaminated World" (Miriam Ticktin)

"Invasive Aliens: The Late-Modern Politics of Species Being" (Jean Comaroff)

"Introduction [to Ecologies element]: Invasive Ecologies" (Rafi Youatt)

"Invasive Others and Significant Others: Strange Kinship and Interspecies Ethics near the Korean Demilitarized Zone" (Eleana Kim)

---

For individual sources:

"The Aliens Have Landed! Reflections on the Rhetoric of Biological Invasion" (Banu Subramaniam, Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 2:1, 2011)

"Loving the Native: Invasive Species and the Cultural Politics of Flourishing" (JR Cattelino, in The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, pp. 145-153, 2017).

"The Rhetoric of Invasive Species: Managing Belonging on a Novel Planet" (Alison Vogelaar, Revue francaise des sciences de l'information et de la communication 21, 2021).

"Invasion Blowback and Other Tales of the Anthropocene: An Afterword." (Anna Tsing. Anthropocenes - Human, Inhuman, Posthuman 4:1, 2023).

Troubling Species: Care and Belonging in a Relational World, a special issue of Transformations in Environment and Societycurated by the Multispecies Editing Collective, 2017.

"Uncharismatic Invasives" (JL Clark, Environmental Humanities 6:1, 2015).

"Involuntary Momentum: Affective Ecologies and the Sciences of Plant/Insect Encounters" (Hustak and Myers, Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 23:3, 2012).

"Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology: An Introduction to Supplement 20" (Tsing, Mathews, and Burbandt, Current Anthropology, 2019).

Trespassing Natures: Species Migration and the Right to Space (Donnie Johnson Sackey, 2024)

Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2016)

Nestwork: New Material Rhetorics for Precarious Species (Jennifer Clary-Lemon)

"Requiem for a junk-bird: Violence, purity and the wild." (Hugo Reinert, Cultural Studies Review 25:1, 2019).

"Comparing Invasive Networks: Cultural and Political Biographies of Invasive Species" (Robbins, Geographical Review 94:2, 2004).

In the Shadow of the Palms: More-than-Human Becomings in West Papua (Sophie Chao, 2022)

"Timing Rice: An Inquiry into More-Than-Human Temporalities of the Anthropocene" (Elaine Gan, New Formations, 2018).

Interspecies Politics: Nature, Borders, States (Rafi Youatt, 2020)

"Interspecies Politics and the Global Rat: Ecology, Extermination, Experiment" (Rafi Youatt, Review of International Studies, 2020)

Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, Routledge, 2015)

"Invasive Narratives and the Inverse of Slow Violence: Alien Species in Science and Society" (Lindstrom, West, Katzschner, Perez-Ramos, and Twidle. Environmental Humanities 7:1, 2016)

"Life Out Of Place: Revisiting Species Invasions. Introduction to the Special Issue" (Hanne Cottyn. Anthropocenes - Human, Inhuman, Posthuman 4:1, 2023).

---

It's been a "transdisciplinary" topic (especially in the past 15-ish years) in environmental humanities, ecocriticism, environmental studies, "science communication," anthropology, etc. (I think the humanities or interdisciplinary scholars handle the subject with more grace than ecology-as-a-field proper.) It shows up a lot in discussion of "the postcolonial," "ecopoetics," "Anthropocene," "multispecies ethnography," and "the posthuman"; Haraway was explicitly writing about rhetoric of invasive species in the 1990s.

A significant amount of posts on my blog from 2018-2022 are about invasive/alien/native labels. I summarized some of the discourses in my post about Colombian hippos. I especially talked a lot about the writing of Banu Subramaniam (rhetoric of ecological invasion, racialization of aliens); Rafi Youatt ("interspecies politics"); Anna Boswell (Aotearoa extinctions, "anamorphic ecology"); Sophie Chao ("post-plantation ecologies"); Elaine Gan ("Anthropocene temporalities" and industrial ruins); Hugo Reinert (species "purity" and extinctions); Puig de la Bellacasa ("speculative ethics in a multispecies world"); Ann Laura Stoler (of fame for her writing on "imperial debris" and ruination/haunting), Hugh Raffles, Nils Burbandt, Anna Tsing, and others. Lately in my own work I've been writing on borders/frontiers and media/colonial imaginaries of "pests/the exotic" and have been referencing Jeannie Shinozuka's Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950.

Thanks for saying hi.

844 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posted about British colonial officials in 1860s South India being fascinated by studying geology of Deccan Plateau as both a potential source of material wealth but also as more like intellectual curiosity that allowed them to consider "deep time" and the place of "civilization" in history. And someone shared post, commenting in tags something sort of like "interesting how British Empire could be so focused on rocks."

And really:

Both British imperial power and British popular imagination are tied to "ancient rocks"

British coal and coal-powered engines transformed global ecologies and societies with railroads and factories at the same time that British public became widely aware of dinosaurs, extinct Pleistocene megafauna, the vast scale of deep time, geology, and uniformitarian Earth systems. Then British anthropology, Egyptomania, archaeology, etc., were implicated in professionalization of sciences and ideas of primitivsm/racial hierarchy. Then British extraction of liquid fossil fuels instantiated expansion of petroleum products. Victorian popular culture had a penchant for contemplating death, decay, deep past, civilizational collapse, classical antiquity. So there's a simultaneous fixation on both temporality and materiality. Which both involve "earth."

-

Consider:

Coal. How the mining of "ancient rock" (300-million-year-old Carboniferous) and coal-burning probably strongly propelled Britain (tied also to enclosure laws and Caribbean slave profits reinvested in ascendant financial/insurance institutions) to the "first" industrialization around 1830, helping cement its global hegemony and setting a blueprint for European/US industry. How burning that ancient rock "unlocked steam power" for Britain and facilitated the rapid expansion of railroad networks after the first public steam railway in 1825 (steam engines then let Britain reach and extract resources from hinterlands) while the rock also powered textile mills after the 1830s (putting poorer Britons to work in mills and factories while "Poor Laws" were put into effect outlawing "vagrancy" and "joblessness") which reshaped "the countryside" in Britain and reshaped global ecologies and labor regimes. Provincial realist novels and other literature reflect anxiety about this ecological/social transition. Even later Victorian novels and fin de siecle commentaries hint how coal and industrialization invoke temporality more directly, in that the engines and technologies provoke rhetoric and discourses about exponential growth, linear progress, and dazzling future horizons.

Fossils of Pleistocene megafauna: How an extinct Mastodon was displayed at Pall Mall in London in 1802. And how William Conybeare's discovery/description of coal-bearing rock in Britain led him to name "the Carboniferous period" in 1822, but it wasn't just coal power that this event inspired. in the very same year, Conybeare described the remains of extinct Pleistocene hyenas at Kirkdale Cave in Britain. The promotion of this discovery of Ice Age hyenas gave many Britons for the first time an awareness of deep past and obsession with Creatures. But the promotion also brought spectacle, public display, poetics, and marketing into natural history like "edu-tainment," a "poetics of popular science." This took place in the context of the rapid rise of British mass-market print media. Geological verse, Victorian novels, and cheap miscellanies reflect anxiety about this temporality and natural history.

Geology as a discipline: How the 1830 publishing of Lyell's monumentally significant Principles of Geology, directly inspired after he observed British ancient rock formations at Isle of Arran, completely changed European/US understanding of deep time and geology and the scale of Earth systems (uniformity principle), which made people wonder about linear notions of history and whether empires/societies can survive forever in such vast time scales.

Dinosaur fossils: How the "first dinosaur sculptures in the world" (dinosaur fossils reminiscent of ancient rock?) were reconstructed and put on display by Britain in 1854 at Crystal Palace in London following "the Great Exhibition," an event which set the model for future exhibitions and started the global craze for "world's fairs" and expositions showcasing imperial/industrial power for decades (the model for Chicago's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Paris event of 1900, St. Louis event of 1904, and beyond).

Soil mapping: How "ancient rock" was entangled with one of the most significant scientific projects of all-time, Britain's "The Great Trigonometric Survey of India" in 1802, undertaken to survey and record soil types across South Asia. After the resistance of the leaders of Mysore had finally been defeated, the subcontinent was vulnerable to consolidated British colonial power, and surveys were ordered immediately. The mapping of acreage for tax administration by the East India Company would remake societies with bordered property, contracted ownership, tax/wealth extraction. But the Survey also let Britain map soil for purposes of monoculture agriculture planning. Britain then used geology/soil as potential indicators of biological essentialism that equated "ancient" Gonds of India or "ancient" Aboriginal peoples of Australia with primitivism. Adventure stories and sportsmen's pulp magazines reflect anxiety about these cultural and geographical frontiers.

Diamonds: How the discovery of ancient rock (diamonds, from tens of millions of years old kimberlite) in the Kimberly (South Africa) rocketed Britain to more power when their colonial commissioners took possession in 1871, giving Britain a foothold and paving the way for Cecil Rhodes to amass astonishing wealth while completely remaking social institutions, labor regimes, and environments in southern Africa, giving Britain so much profit from diamonds that in 1882 Kimberly was only the second city on the whole planet to install electric street lighting.

Egyptomania: How British archaeologists digging around in ancient rock of their vassal/colony of Egypt, especially the tens of thousands of ancient Egyptian artifacts that they collected between 1880 and 1890, contributed to a craze for classical antiquity and a fixation on the ancient Mediterranean and mummies.

Victorian death fascination: How British archaeologists interacting with ancient rock in Southwest Asia (Mesopotamia, Levant) coupled with the Egyptomania also strongly influenced Late Victorian obsessions with death, decay, the occult, millennarian dates, and civilizational collapse which continued to influence culture, fashion, historicity, and narrativizing in Europe/US for years. Perhaps they wondered: "If Ur could fall, if Thebes could fall, if Mycenae could fall, if ROME could fall, then how could our civilization based in fair London survive such vast eons of time and such strong geological and environmental forces?"

Liquid fossil fuels: How "ancient rock" yielded liquid fossil that was extracted by British industrialsits when the first test oil wells were dug at "the Black Spot" in Borneo in 1896 which led to creation of Shell Oil company in 1897 led by a British director who was fascinated with ancient fossils. Followed then the global expansion of combustion engines, oil lubricants, and networks of imperial infrastructure to extract and refine oil. And how British tinkering with "ancient rock" of Persia and Southwest Asia led to the bolstering of a "Middle East" oil industry; the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was founded in 1909, giving Britain yet more geopolitical leverage in the region; the company would later become BP, one of the biggest and most profitable corporations to ever exist.

-

So the immaterial imaginaries of place/space and time (frontiers, the exotic/foreign, the tropical/Orient, ascent/decay, civilization/savagery, deep past/future horizons) justify or organize or pre-empt or service the material dispossession and accumulation.

British Empire transformed Earth and earth. Both materially/physically and immaterially/imaginatively.

399 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the Reverse Unpopular Opinion meme, Lamarckism!

(This is an excellent ask.)

Lamarck got done a bit dirty by the textbooks, as one so often is. He's billed as the guy who articulated an evolutionary theory of inherited characteristics, inevitably set up as an opponent made of straw for Darwin to knock down. The example I recall my own teachers using in grade school was the idea that a giraffe would strain to reach the highest branches of a tree, and as a result, its offspring would be born with slightly longer necks. Ha-ha-ha, isn't-that-silly, isn't natural selection so much more sensible?

But the thing is, this wasn't his idea, not even close. People have been running with ideas like that since antiquity at least. What Lamarck did was to systematize that claim, in the context of a wider and much more interesting theory.

Lamarck was born in to an era where natural philosophy was slowly giving way to Baconian science in the modern sense- that strange, eighteenth century, the one caught in an uneasy tension between Newton the alchemist and Darwin the naturalist. This is the century of Ben Franklin and his key and his kite, and the awed discovery that this "electricity" business was somehow involved in living organisms- the discovery that paved the way for Shelley's Frankenstein. This was the era when alchemy was fighting its last desperate battles with chemistry, when the division between 'organic' and 'inorganic' chemistry was fundamental- the first synthesis of organic molecules in the laboratory wouldn't occur until 1828, the year before Lamarck's death. We do not have atoms, not yet. Mendel and genetics are still more than a century away; we won't even have cells for another half-century or more.

Lamarck stepped in to that strange moment. I don't think he was a bold revolutionary, really, or had much interest in being one. He was profoundly interested in the structure and relationships between species, and when we're not using him as a punching bag in grade schools, some people manage to remember that he was a banging good taxonomist, and made real progress in the classification of invertebrates. He started life believing in the total immutability of species, but later was convinced that evolution really was occurring- not because somebody taught him in the classroom, or because it was the accepted wisdom of the time, but through deep, continued exposure to nature itself. He was convinced by the evidence of his senses.

(Mostly snails.)

His problem was complexity. When he'd been working as a botanist, he had this neat little idea to order organisms by complexity, starting with the grubbiest, saddest little seaweed or fern, up through lovely flowering plants. This was not an evolutionary theory, just an organizing structure; essentially, just a sort of museum display. But when he was asked to do the same thing with invertebrates, he realized rather quickly that this task had problems. A linear sorting from simple to complex seemed embarrassingly artificial, because it elided too many different kinds of complexity, and ignored obvious similarities and shared characteristics.

When he went back to the drawing board, he found better organizing schema; you'd recognize them today. There were hierarchies, nested identities. Simple forms with only basic, shared anatomical patterns, each functioning as a sort of superset implying more complex groups within it, defined additively by the addition of new organs or structures in the body. He'd made a taxonomic tree.

Even more shockingly, he realized something deep and true in what he was looking at: this wasn't just an abstract mapping of invertebrates to a conceptual diagram of their structures. This was a map in time. Complexities in invertebrates- in all organisms!- must have been accumulating in simpler forms, such that the most complicated organisms were also the youngest.

This is the essential revolution of Lamarckian evolution, not the inherited characteristics thing. His theory, in its full accounting, is actually quite elaborate. Summarized slightly less badly than it is in your grade school classroom (though still pretty badly, I'm by no means an expert on this stuff), it looks something like this:

As we all know, animals and plants are sometimes generated ex nihilo in different places, like maggots spontaneously appearing in middens. However, the spontaneous generation of life is much weaker than we have supposed; it can only result in the most basic, simple organisms (e.g. polyps). All the dizzying complexity we see in the world around us must have happened iteratively, in a sequence over time that operated on inheritance between one organism and its descendants.

As we all know, living things are dynamic in relation to inorganic matter, and this vital power includes an occasional tendency to gain in complexity. However, this tendency is not a spiritual or supernatural effect; it's a function of natural, material processes working over time. Probably this has something to do with fluids such as 'heat' and 'electricity' which are known to concentrate in living tissues. When features appear spontaneously in an organism, that should be understood as an intrinsic propensity of the organism itself, rather than being caused by the environment or by a divine entity. There is a specific, definite, and historically contingent pattern in which new features can appear in existing organisms.

As we all know, using different tissue groups more causes them to be expressed more in your descendants, and disuse weakens them in the same way. However, this is not a major feature in the development of new organic complexity, since it could only move 'laterally' on the complexity ladder and will never create new organs or tissue groups. At most, you might see lineages move from ape-like to human-like or vice versa, or between different types of birds or something; it's an adaptive tendency that helps organisms thrive in different environments. In species will less sophisticated neural systems, this will be even less flexible, because they can't supplement it with willpower the way that complex vertebrates can.

Lamarck isn't messing around here; this is a real, genuinely interesting model of the world. And what I think I'm prepared to argue here is that Lamarck's biggest errors aren't his. He has his own blind spots and mistakes, certainly. The focus on complexity is... fraught, at a minimum. But again and again, what really bites him in the ass is just his failure to break with his inherited assumptions enough. The parts of this that are actually Lamarckian, that is, are the ideas of Lamarck, are very clearly groping towards a recognizable kind of proto-evolutionary theory in a way that we recognize.

What makes Lamarck a punching bag in grade-school classes today is the same thing that made it interesting; it's that it was the best and most scientific explanation of biological complexity available at the time. It was the theory to beat, the one that had edged out all the other competitors and emerged as the most useful framework of the era. And precisely none of that complexity makes it in to our textbooks; they use "Lamarckianism" to refer to arguments made by freaking Aristotle, and which Lamarck himself accepted but de-emphasized as subordinate processes. What's even worse, Darwin didn't reject this mechanism either. Darwin was totally on board with the idea as a possible adaptive tendency; he just didn't particularly need it for his theory.

Lamarck had nothing. Not genetics, not chromosomes, not cells, not atomic theory. Geology was a hot new thing! Heat was a liquid! What Lamarck had was snails. And on the basis of snails, Lamarck deduced a profound theory of complexity emerging over time, of the biosphere as a(n al)chemical process rather than a divine pageant, of gradual adaptation punctuated by rapid innovation. That's incredible.

There's a lot of falsehood in the Lamarckian theory of evolution, and it never managed to entirely throw off the sloppy magical thinking of what came before. But his achievement was to approach biology and taxonomy with a profound scientific curiosity, and to improve and clarify our thinking about those subjects so dramatically that a theory of biology could finally, triumphantly, be proven wrong. Lamarck is falsifiable. That is a victory of the highest order.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

[Image Source]

Gene Behind Orange Fur in Cats Found at Last

Shared from Science.org.

It would be pretty easy to guess that Garfield was a tomcat even if you didn’t know his name—or didn’t want to peek under his tail. Most orange cats are boys, a quirk of feline genetics that also explains why almost all calicos and tortoiseshells are girls.

Scientists curious about those sex differences—or perhaps just cat lovers—have spent more than 60 years unsuccessfully seeking the gene that causes orange fur and the striking patchwork of colors in calicos and tortoiseshells. Now, two teams have independently found the long-awaited mutation and discovered a protein that influences hair color in a way never seen before in any animal.

“I am fully convinced this is the gene and am happy,” says Carolyn Brown, a University of British Columbia geneticist who was not involved in either study. “It’s a question I’ve always wanted the answer to.”

Scientists have long been fascinated by tortoiseshell and calico cats: the offspring of a black cat and an orange cat. Multicolored cats from such a cross are almost always female, suggesting the gene variant that makes fur orange or black is located on the X chromosome. The male offspring of such a cross are typically unicolor because they inherit just one parent’s X chromosome: We can guess, for instance, that Garfield’s mother is orange because he inherited his only X chromosome from her.**

But female cats inherit an X chromosome from each parent. Cells don’t generally need both, so during embryonic development each cell randomly chooses one X to express genes from. The other chromosome rolls up into a mostly inert ball—a phenomenon called X inactivation. As a result, tortoiseshell cats end up with separate patches of black and orange fur depending on which chromosome was inactivated in that part of their skin. Calico cats add white fur into the mix because they have a second, unrelated genetic mechanism that shuts down pigment production in some cells.

In most mammals, including humans, red hair is caused by mutations in one cell surface protein, Mc1r, that determines whether skin cells called melanocytes produce a dark pigment or a lighter red-yellow pigment in skin or hair. Mutations that make Mc1r less active cause melanocytes to get “stuck” producing the light pigment.

But the gene encoding Mc1r didn’t seem explain where cats’ orange fur came from. It isn’t located on the X chromosome in cats or any other species—and most orange cats don’t have Mc1r mutations. “It’s been a genetic mystery, a conundrum,” says Greg Barsh, a geneticist at Stanford University.

To solve it, Barsh’s team collected skin samples from four orange and four nonorange fetuses from cats at spay-neuter clinics. As a proxy to determine how individual skin cells express genes, the researchers measured the amount of RNA that each melanocyte was producing and determined the gene it encoded. Melanocytes from orange cats, they found, made 13 times as much RNA from a gene called Arhgap36. The gene is located on the X chromosome, which led the team to think they had the key to orange color.

But when the researchers looked at Arhgap36’s genetic sequence in orange cats, they didn’t find any mutations in the DNA that encodes the Arhgap36 protein. Instead, they found the orange cats were missing a nearby stretch of DNA that didn’t affect the protein’s amino acid components but might be involved in regulating how much of it the cell produced. Scanning a database of 188 cat genomes, Barsh’s team found every single orange, calico, and tortoiseshell cat had the exact same mutation. The group reports the discovery this month on the preprint server bioRxiv.

A separate study, also posted to bioRxiv this month, confirms these findings. Similar experiments run by developmental biologist Hiroyuki Sasaki at Kyushu University and his colleagues revealed the same genetic deletion in 24 feral and pet cats from Japan, as well as among 258 cat genomes collected from around the world. They also found that skin from calico cats had more Arghap36 RNA in orange regions than in brown or black regions. Moreover Arhgap36 genes in mice, cats, and humans acquire chemical modifications that silence them on one of the two X chromosomes in females, Sasaki’s team documented, suggesting the gene is subject to X inactivation.

When Barsh and Sasaki learned their respective teams had discovered the same mutation, they decided to post their preprints at the same time. (Because they are preprints, neither study has been peer reviewed.) Both groups further found that increasing the amount of Arhgap36 in melanocytes activates a molecular pathway that switches the cells to producing light red pigment regardless of whether MC1r is active.

No one previously knew Arhgap36 could affect skin or hair coloration—it is involved in many aspects of embryonic development, and major mutations that affect its function throughout the body would probably kill the animal, Barsh says. But because the deletion mutation appears to only affect Arhgap36 function in melanocytes, cats with the mutation are not only healthy, but also cute.

Arhgap36’s inactivation pattern in calicos and tortoiseshells is typical of a gene on the X chromosome, Brown says, but it’s unusual that a deletion mutation would make a gene more active, not less. “There is probably something special about cats.”

Experts are thrilled by the two studies. “It’s a long-awaited gene,” says Leslie Lyons, a feline geneticist at the University of Missouri. The discovery of a new molecular pathway for hair color was unexpected, she says, but she’s not surprised how complex the interactions seem to be. “No gene ever stands by itself.”

Lyons would like to know where and when the mutation first appeared: There is some evidence, she says, that certain mummified Egyptian cats were orange. Research into cat color has revealed all kinds of phenomena, she says, including how the environment influences gene expression. “Everything you need to know about genetics you can learn from your cat.”

A Deletion at the X-linked Arhgap36 Gene Locus is Associated With the Orange Coloration of Tortoiseshell and Calico Cats

Molecular and Genetic Characterization of Sex-linked Orange Coat Color in the Domestic Cat

**Minor correction: Garfield’s mother could also have been a tortoiseshell.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The irony of doing deforestation in a land that already has nearly no forests, only to place some giant bird-killing things there in the name of “green energy.” Don’t let me even get started about how much harmful manufacturing processes need to take place to make wind turbines.

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Once thought to be extinct, black-footed ferrets are the only ferret native to North America, and are making a comeback, thanks to the tireless efforts of conservationists.

Captive breeding, habitat restoration, and wildlife reintegration have all played a major role in bringing populations into the hundreds after near total extinction.

But one other key development has been genetic cloning.

In April [2024], the United States Fish and Wildlife Service announced the cloning of two black-footed ferrets from preserved tissue samples, the second and third ferret clones in history, following the birth of the first clone in December 2020.

Cloning is a tactic to preserve the health of species, as all living black-footed ferrets come from just seven wild-caught descendants. This means their genetic diversity is extremely limited and opens them up to greater risks of disease and genetic abnormalities.

Now, a new breakthrough has been made.

Antonia, a black-footed ferret cloned from the DNA of a ferret that lived in the 1980s has successfully birthed two healthy kits of her own: Sibert and Red Cloud.

These babies mark the first successful live births from a cloned endangered species — and is a milestone for the country’s ferret recovery program.

The kits are now three months old, and mother Antonia is helping to raise them — and expand their gene pool.

In fact, Antonia’s offspring have three times the genetic diversity of any other living ferrets that have come from the original seven ancestors.

Researchers believe that expanded genetic diversity could help grow the ferrets’ population and help prime them to recover from ongoing diseases that have been massively detrimental to the species, including sylvatic plague and canine distemper.

“The successful breeding and subsequent birth of Antonia's kits marks a major milestone in endangered species conservation,” said Paul Marinari, senior curator at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.

“The many partners in the Black-footed Ferret Recovery Program continue their innovative and inspirational efforts to save this species and be a model for other conservation programs across the globe.”

Antonia actually gave birth to three kits, after mating with Urchin, a 3-year-old male ferret. One of the three kits passed away shortly after birth, but one male and one female are in good health and meeting developmental milestones, according to the Smithsonian.

Mom and babies will remain at the facility for further research, with no plans to release them into the wild.

According to the Colorado Sun, another cloned ferret, Noreen, is also a potential mom in the cloning-breeding program. The original cloned ferret, Elizabeth Ann, is doing well at the recovery program in Colorado, but does not have the capabilities to breed.

Antonia, who was cloned using the DNA of a black-footed ferret named Willa, has now solidified Willa’s place as the eighth founding ancestor of all current living ferrets.

“By doing this, we’ve actually added an eighth founder,” said Tina Jackson, black-footed ferret recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in an interview with the Colorado Sun.

“And in some ways that may not sound like a lot, but in this genetic world, that is huge.”

Along with the USFWS and Smithsonian, conservation organization Revive & Restore has also enabled the use of biotechnologies in conservation practice. Co-founder and executive director Ryan Phelan is thrilled to welcome these two new kits to the black-footed ferret family.

“For the first time, we can definitively say that cloning contributed meaningful genetic variation back into a breeding population,” he said in a statement.

“As these kits move forward in the breeding program, the impact of this work will multiply, building a more robust and resilient population over time.”"

-via GoodGoodGood, November 4, 2024

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

“How can we distinguish what is biologically determined from what people merely try to justify through biological myths? A good rule of thumb is ‘Biology enables, culture forbids.’ Biology is willing to tolerate a very wide spectrum of possibilities. It’s culture that obliges people to realise some possibilities while forbidding others. Biology enables women to have children – some cultures oblige women to realise this possibility. Biology enables men to enjoy sex with one another – some cultures forbid them to realise this possibility. Culture tends to argue that it forbids only that which is unnatural. But from a biological perspective, nothing is unnatural. Whatever is possible is by definition also natural. A truly unnatural behaviour, one that goes against the laws of nature, simply cannot exist, so it would need no prohibition. No culture has ever bothered to forbid men to photosynthesise, women to run faster than the speed of light, or negatively charged electrons to be attracted to each other. In truth, our concepts ‘natural’ and unnatural’ are taken not from biology, but from Christian theology. The theological meaning of ‘natural’ is ‘in accordance with the intentions of the God who created nature’. Christian theologians argued that God created the human body, intending each limb and organ to serve a particular purpose. If we use our limbs and organs for the purpose envisioned by God, then it is a natural activity. To use them differently than God intends is unnatural. But evolution has no purpose. Organs have not evolved with a purpose, and the way they are used is in constant flux. There is not a single organ in the human body that only does the job its prototype did when it first appeared hundreds of millions of years ago. Organs evolve to perform a particular function, but once they exist, they can be adapted for other usages as well. Mouths, for example, appeared because the earliest multicellular organisms needed a way to take nutrients into their bodies. We still use our mouths for that purpose, but we also use them to kiss, speak and, if we are Rambo, to pull the pins out of hand grenades. Are any of these uses unnatural simply because our worm-like ancestors 600 million years ago didn’t do those things with their mouths?”

— Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Harari, Yuval Noah)

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

Born too early to explore the galaxy, born at just the right time to watch biologists make some buck wild discoveries about the evolution and classification of archaea

It’s crazy to me that modern genetics gives us the tools to figure out which clade within the Asgard archaea probably gave rise to the eukaryotes and allows us to pretty effectively sort many families of single celled organism in evolutionary history despite all this shit happening in the Precambrian and leaving basically no fossil evidence

618 notes

·

View notes

Text

will quickly say that. i deifnitely see why everyone loves coelacanths and why they're the most popular/well known of the lobefins (excluding us tetrapods), not just because they are fascinating creatures but because of the story of their discovery, but i can't help but feel like they overshadow their lungfish cousins a little. lungfish need more LOVE!!!!!

they're the closest relative of us tetrapods that're still extant today, closer to us than coelacanths, they LITERALLY have lungs hence the name and i'm pretty sure one or two species of lungfish are obligate airbreathers--meaning these are fish species that can drown. queensland lungfish in particular fascinate me, cause they have the most developed fins, and it REALLY gives me a feel of what our early, fishy tetrapod ancestors would look like!

plus....they're just plain cute :)

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

People who like mantises but aren't that into entomology are always "orchid mantises" this and "orchid mantises" that. Overrated. Can we talk about Toxodera integrifolia for a minute:

(Image links because as much as it pains me I've never seen one of these beauties irl: 1 2 3)

Like how are these things real. Girl what is that thorax shape. Why are you wearing eyeliner. And the colors? Absolutely fire. This is a 10/10 insect if you ask me.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

People who like mantises but aren't that into entomology are always "orchid mantises" this and "orchid mantises" that. Overrated. Can we talk about Toxodera integrifolia for a minute:

(Image links because as much as it pains me I've never seen one of these beauties irl: 1 2 3)

Like how are these things real. Girl what is that thorax shape. Why are you wearing eyeliner. And the colors? Absolutely fire. This is a 10/10 insect if you ask me.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

« Animals might see crisp detail at a distance, or nothing more than blurry blotches of light and shade. They might see perfectly well in what we’d call darkness, or go instantly blind in what we’d call brightness. They might see in what we’d deem slow motion or time-lapse. They might see in two directions at once, or in every direction at once. Their vision might get more or less sensitive over the span of a single day. Their Umwelt might change as they get older. Jakob’s colleague Nate Morehouse has shown that jumping spiders are born with their lifetime’s supply of light-detecting cells, which get bigger and more sensitive with age. “Things would get brighter and brighter,” Morehouse tells me. For a jumping spider, getting older “is like watching the sun rising." »

— Ed Yong, An Immense World

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

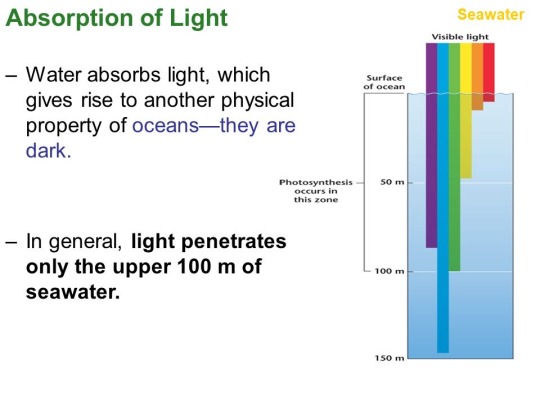

sometimes I think about how red is the first color in the visible light spectrum to be absorbed in ocean water

and how many deep-sea creatures evolved to be red as a stealth adaptation, making them near invisible when there’s little to no light present

and it makes me think. If there’s never any visible light present in these animals’ lifetimes, if no ROV shines a little flashlight in depths that would otherwise not have light, would these animals ever get the opportunity to actually be red? that might be a stupid question.

imagine being a little deep sea creature and having no idea you’re red until something comes along and shines a light on you except you still wouldn’t be able to tell because you’re probably colorblind. anyway. I don’t know where I was going with this post

95K notes

·

View notes