Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

debbie downer and negative nancy should lez out

77K notes

·

View notes

Text

My Girlfriend’s Not Here Today - Kiyoko Iwami

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

C A N E N D A R

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

Arahsamnum 2021: Nungal

Yesterday’s post covered nebulous deities who, by the virtue of being at various points in time and space regarded as Nergal’s wives Today’s topic is instead a goddess who, while also known as a daughter in law of Enlil and Ninlil, is decidedly less nebulous than her husband. Nungal (also known as Manungal) was the goddess of prisons, and her husband was the obscure god Birdum. How obscure? It will suffice to say -I- was unable to find out much of value about his nature.

Keep reading

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

1000 followers special: the history of the hakutaku

I recently hit a major milestone. It would appear that over a thousand people apparently want to see more on their dashboards. To celebrate, I decided to go back to the roots of this blog. While I doubt many of you remember it, some of my first posts were complaints about Touhou fanworks failing to account for the fact that the hakutaku was not a boogeyman, but a good luck charm. In this article, I will explain how come, what exactly the role of an "auspicious beast" entailed, and how different people utilized the story of the hakutaku through history. I will also check how does the Touhou portrayal compare to the historical sources - though that's not the only case of modern reception you will be able to learn about. As usual, more under the cut.

The earliest history of the hakutaku As in the case of many other Japanese mythological beings, the history of the hakutaku actually starts in China. The creature was originally known as baize (白澤); hakutaku is simply the Japanese reading. The name can be literally translated as “white marsh”, but how it initially developed is unknown. Donald Harper argues that baize can effectively be considered a deity. For what it’s worth, there is clear evidence that it could be invoked in theophoric names in the first millennium. The first known case is a certain Zhang Zhongkui (張鍾葵; obviously, his old name is related to the well known figure of the demon queller Zhong Kui) from Northern Wei, who was renamed Zhang Baize (張白澤) by emperor Xianwen. Crown prince Xiao Zhangmao of the Southern Qi was nicknamed Baize, too. Multiple other examples are apparently known, but sadly I was unable to track down any information beyond a confirmation they existed. Generally speaking, the baize played an apotropaic role. Bernard Faure argues that the creature effectively fulfilled many of the roles of the fangxiangshi, a class of ancient exorcists. Pictures of it could be hung in houses to ward off malign spirits and misfortune. Textual sources indicate this custom was widespread among various social strata. Images of the baize could also be embroidered on clothes, banners and other items. An interesting practice tied to this is documented in sources pertaining to the life of empress Wei from the Tang dynasty. Reportedly her younger sister Qiyi (七姨) slept on a pillow with a depiction of the baize to ward off malicious spirits.

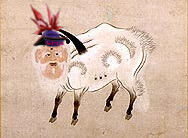

A typical illustration of various creatures from the Shanhaijing (from Richard E. Strassberg's translation; reproduced here for educational purposes only) While the Tang period is when the belief in baize flourished, the creature was actually older. The first references have been dated to the fourth century. Sometimes even in academic publications you can find claims that it is as old as the Shanhaijing, but this is a mistake. It is true that copies of Shanhaijing which mention the baize exist, but they were only produced in the Ming period and the description was likely sourced from a contemporary encyclopedia, Sancai Tuhui. It is not impossible that the baize ultimately did originate before the Six Dynasties period, but this cannot be proven conclusively. From Baopouzi to Dunhuang manuscripts: Baize, the Yellow Emperor and the Baize Tu The first certain attestation of the baize has been identified in Ge Hong’s Baopuzi, which you might remember from my Ten Desires and Zanmu articles. In the section dedicated to the Yellow Emperor, the author states that in addition to his other famous deeds, this legendary ruler recorded the words of the baize. A more detailed account of this event in preserved in a more recent source, the Yunji Qiqian, specifically in the chapter Xuanyuan benji (軒轅本紀; “Basic annals of Xuanyuan”, ie. the Yellow Emperor). It relays how the Yellow Emperor encountered the baize on Mount Huan (桓山) during a hunting expedition to the eastern frontiers of his kingdom, close to the sea. The creature appeared before him to share esoteric knowledge. It relayed that there are eleven thousand five hundred and twenty types of malign beings, the “spectral prodigies” (精怪, jing guai), in the world, and explained how people could protect themselves from each of them. There’s no real theme to the creatures mentioned: they include animal spirits, spirits of places and objects (for example a stove), as well as various beings which can be broadly described as genius loci. The key to overcoming them was to know their true names. This is not a belief unique to the baize tradition. The Yellow Emperor ordered this to be written down so that this knowledge can be preserved and further disseminated. The compilation of baize’s advice came to be known as the Baize Tu (白澤圖), literally “Diagrams of White Marsh”. This tradition must predate Ge Hong, as he mentions the Baize Tu as a work which can be consulted to gain additional insights when it comes to repelling demons. However, he does not connect it with the Yellow Emperor legend directly. Multiple other sources attest that various variants of this treatise actually existed. Song shi (宋史; “History of the Song”), attributes its composition to a certain Li Chunfeng (李淳風; 602–670). Despite apparently relatively wide circulation, every single version of this work is now lost, save for a ninth or tenth century fragment discovered in Dunhuang, the so-called Baize Jingguai Tu (白澤精怪圖), “White Marsh Diagram of Spectral Prodigies”. It was originally identified by Jao Tsung-i in the 1960s, around 60 years after discovery. The surviving sections describe and depict some of the, well, “spectral prodigies”, as promised by the title, as you can see below:

Illustrations sourced from a recent reprint of Jao Tsung-i's article, via Brill; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

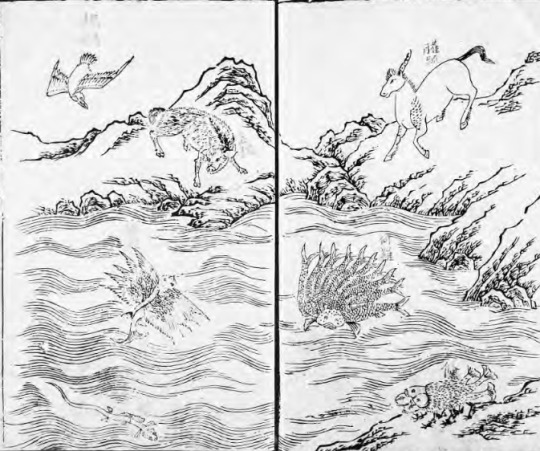

Other manuscripts from Dunhuang mention the baize alongside Zhong Kui in the context of new year celebrations. As both of them were believed to keep nefarious forces at bay through different methods, it presumably felt natural to invoke both at once. The Dunhuang texts discussing the baize do not contain any images of the creature. However, the exact same site did provide us with a depiction of it, most likely:

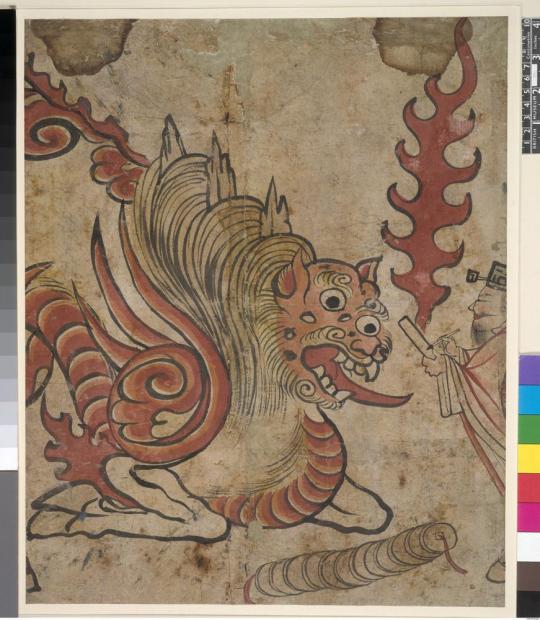

The supposed baize painting from Dunhuang (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

While the enormous creature in painting above was initially interpreted as some sort of longma, according to Donald Harper its distinctly cow-like shape indicates it should be interpreted baize. The human figure is presumably a scribe, which might indicate we’re dealing with a pictorial version of the legend about Yellow Emperor’s encounter with the baize. After all, someone had to be present to write the creature’s advice down, as requested. The string of coins might be there to provide the image with further apotropaic qualities - the use of coins as talismans is a well established part of new year customs dating as far back as the Tang period. That’s actually where the modern custom of giving kids money in red envelopes comes from. While the supposed baize painting is a unique and remarkable work of art from a modern perspective, it was likely not regarded as such when originally made. At some point parts of it have been cut, and a Buddhist woodblock print has been pasted on top of it (obviously they were separated during restoration). Before that it was presumably meant to serve as an ephemeral amulet, discarded after it had served its purpose. This obviously does not diminish its value as a historical source. History is not just just about grand codes of law or royal declarations, as the fact that the study of the culture of some of the oldest states rests largely on the equivalent of receipts and school exercises. I guarantee that in a few hundred years trivial newspaper articles will similarly be the subject of serious inquiries. Buddhist reception of the baize

A Chinese depiction of Manjushri (wikimedia commons) Baize also occurs in Buddhist sources from the Tang period, where the creature is linked to Manjushri. This was rooted in a new development, namely the reinterpretation of this bodhisattva as a figure associated with auspicious signs, rather than his traditional domain, wisdom. Additionally, it was presumably easy to link an at least semi-divine distinctly bovine creature with the custom of referring to certain buddhas and bodhisattvas with the title of “ox king” (牛王). The first source to mention the association between the baize and Manjushri is a text written by the Buddhist monk Kuiji (632-682), a disciple of the famous Xuanzang. He states that a cow giving birth to a baize is one of the signs that the rebirth of Manjushri draws closer, similarly to a feng bird hatching from a chicken egg, a horse giving birth to a qilin, or an elephant with six tusks appearing. As you can see, the baize is in esteemed company here. For instance, the qilin was said to only appear to virtuous rulers, while the six-tusked elephant appears in the traditional account of the historical Buddha’s birth. This tradition is also documented in the Sutra of Manjushri’s Auspicious Signs (文殊吉祥經,Wenshu Jixiang Jing), only known from a small fragment. Here the birth of the baize is actually elevated to the rank of the final omen in the cycle preceding the appearance of the eponymous bodhisattva. The text also alludes to the baize’s apotropaic role as a figure meant to ward off demons. Additionally it states that the creature normally lives in heaven, but can choose to reincarnate on earth, among humans - obviously to foretell the birth of Manjushri. Apparently all of the “auspicious beasts and numinous birds” rejoice when that happens.

The decline of baize in China It seems that after the Tang period, the popularity of the baize declined in China, mostly at the expense of Zhong Kui. It was not a complete disappearance, but while the early baize largely belonged in the domain of popular belief, later on most attestations reflect courtly and scholarly interests only. For unknown reasons at some point baize’s iconography was reinvented, with the ox-like form replaced by one with leonine features. The Southern Song encyclopedia Gujin Hebi Shilei Beiyao outright suggests baize is simply a term referring to lions. In a source from the Yuan period, a banner depicting the baize as a creature with “tiger head, red hair with horns, dragon body” is mentioned, though, so evidently not everyone accepted this rationalization. Some references to the baize can still be found in texts from the Qing period. One example is a poem by a Tiantai Buddhist monk, Zhang Hengwu (張亨梧; 1633–1708), based on the well established Yellow Emperor narrative. In his version, the legendary ruler specifically seeks the baize while traveling to the east. Japanese reception of the baize

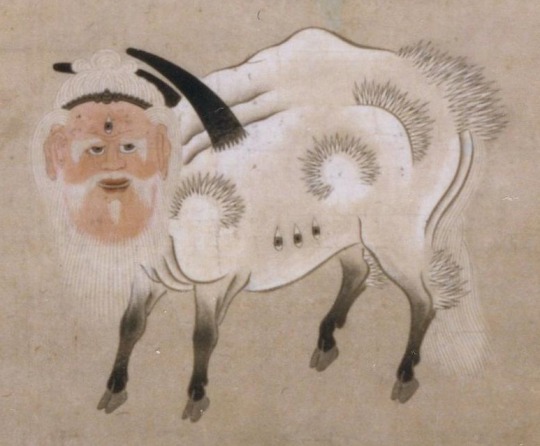

The baize/hakutaku, as depicted by Gusukuma Seihō (wikimedia commons)

Baize’s illustrious career was not limited to one country. At some point, the creature was also introduced to Japan. Most likely it reached the archipelago either through Buddhist sources or Sa Shouzhen’s (薩守真) treatise Tiandi Ruixiang Zhi (天地瑞祥志; “Treatise on auspicious signs in heaven and earth”). The latter was transmitted to Japan as early as in the ninth century, and it is possible the baize - or rather the hakutaku, following the Japanese reading of the name - was already recognized as an apotropaic creature in Japan at this time. By the 1200s, the belief in its auspicious power was well established. Tachibana no Narisue states in Kokon Chomonjū (1254) that in the private chambers of the emperor (Seiryōden) there was an “oni room” (鬼の間, oni no ma) in which a painting of hakutaku repelling demons was displayed. Japanese art did not adopt the younger Chinese convention of portraying the creature as leonine. It was not entirely unknown, with the best known example being an illustration from the Edo period encyclopedia Wakan Sansai Zue, but it never became popular. The ox-like shape remained the norm. The iconography of the hakutaku is thus pretty consistent: the body of a white ox, the head of an old man with a vertical third eye and sometimes a pair of horns, plus additional eyes and horns on the flanks. The human head might be a Japanese innovation, reflecting the ability of human speech ascribed to the creature. Probably the single best known Japanese depiction of the hakutaku is that painted by Gusukuma Seihō (1614-1644). He was the official painter of the royal court of Ryukyu and somewhat of an international celebrity in his times, considering his work was renowned not just in his homeland, but also among Chinese envoys to Ryukyu and by the Tokugawa court. Sadly, this is his only surviving painting, unless there are more in private collections inaccessible to historians (this is not impossible, and reportedly a second hakutaku painting attributed to him belonged to a private Okinawan collector in the 1920s at the very least). As noted by Bernard Faure, hakutaku was effectively a visual reversal of Gozu Tenno, who could be portrayed as a man with a bull’s head, and often played a similar apotropaic role. Additionally, through the title of “ox king”, which recurs in Japanese sources, hakutaku can be indirectly linked to many other major figures of esoteric Buddhism, including Daiitoku Myōō, Ishana and Yama. If you really want to stretch it you can even make a case for parallels with Matarajin, considering both his demon-repelling properties and his association with oxen.

Hakutaku and baku

The baku, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

As mentioned by the sixteenth century author Naotomo Isshiki (一色直朝), in addition to warding off demons hakutaku was also believed to eat bad dreams. This indicates confusion or conflation with the baku. The two are also treated as synonymous in Gen’i Nagoya’s (名古屋玄医; 1628-1696) Minkan Saijiki (民間歲時記 ; “Everyman’s record of the year and seasons”), which is about a century younger. He pretty clearly describes the hakutaku rather than the baku, since the “diagrams” known from Chinese sources and the Yellow Emperor legend are both mentioned. The original tradition must have been well known at least among

“King baku” (Gohyaku Rakanji website; reproduced here for educational purposes only) By far the best example of this phenomenon of conflationg baku and hakutaku a statue from Gohyaku Rakanji (“Temple of the Five Hundred Arhats”) which depicts a hakutaku, but is referred to as “king baku” (獏王) today. It was originally sculpted by the monk Shōun (松雲; 1648 - 1710) in the late seventeenth century, much like the rest of the still displayed statuary. I actually first learned about the hakutaku in 2012 or so from the baku article on Zack Davidsson’s blog Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, which mentions the Gohyaku Rakanji statue and the conflation between the two creatures. Lafcadio Hearn also asserted hakutaku is simply another name for baku.

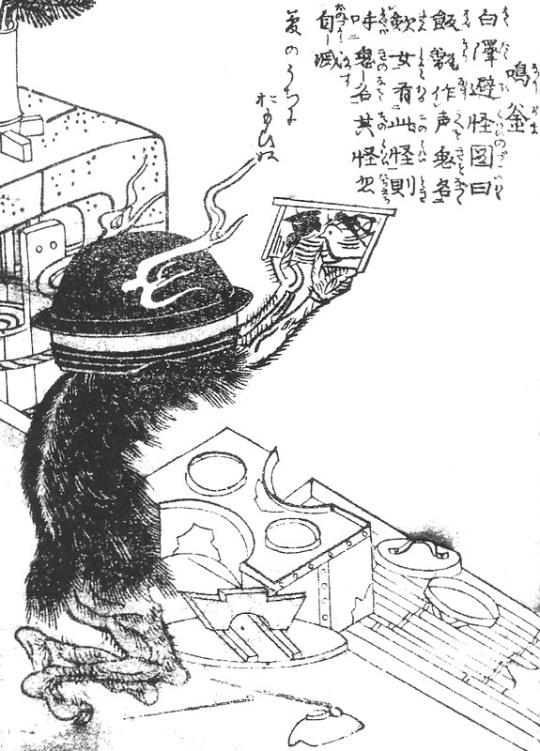

Hakutaku in the Edo period For unknown reasons the popularity of hakutaku increased in the Edo period, especially over the course of the eighteenth century. Sekien Toriyama included it in one of his compilations of yokai illustrations. He also refers to the hakutaku (or rather to baize, as the note is in Chinese) in his description of the narigama (a type of tsukomogami), stating that the way to get rid of this creature’s forerunner renjo was shared with humans by the auspicious beast.

The norigama illustration in mention (wikimedia commons)

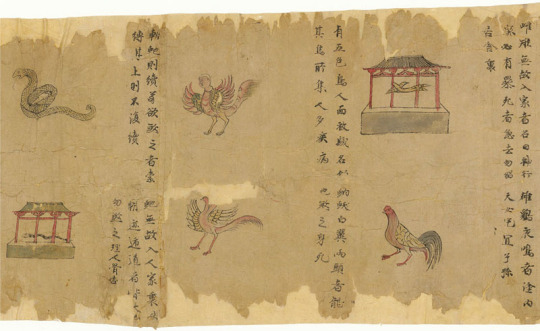

Most importantly, amulets depicting hakutaku were used for protection while traveling and to ward off illness and misfortune. This custom relied on a Chinese source, the twelfth century treatise Sheshi lu (涉世錄), literally “Record of Experiencing the World” which prescribed hanging an image of the baize at home to prevent misfortune. This work is now lost and the relevant passage, known from quotations in Japanese sources, is its longest surviving section. The increase in apotropaic usage of hakutaku images lead to the creation of the so-called White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies (白澤避怪圖, Hakutaku Hikai Zu). This term refers to talismans consisting of a painting of the creature and a short version of the already discussed Yellow Emperor legend. It culminates in a scene with no Chinese forerunner, in which the hakutaku announces to the emperor that hanging an image representing it in a house protects from, well, “ominous prodigies”. A list of some of them was also provided. The Zen monk Hakuin (白隱; 1686–1768) already describes the hakutaku talismans as popular, though he stresses neither he nor the people using them were aware of their origin. The precise history of their development remains unknown to researchers too. Seemingly they couldn’t be older than the seventeenth century at the earliest. Why did apotropaic images of hakutaku aimed at general population resurface in Japan centuries after their use ceased in China is unknown. Their spread might have been tied with the practices of the shugenja, as many of them were distributed among pilgrims visiting Mt. Togakushi, a well known center of the Shugendo tradition.

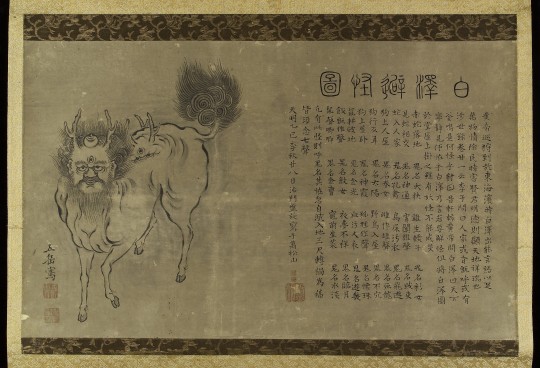

The most famous apotropaic depiction of hakutaku (wikimedia commons)

A well known example of the White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies, presently in the collection of the British Museum, was painted by Gogaku Fukuhara, with the text provided by the Buddhist monk Bansen (盤旋). Based on the colophon of their work, it was completed on October 30, 1785. It’s worth highlighting that it situates the creature in Buddhist context (if that was not clear enough from the involvement of a monk), as the structure on its head is pretty clearly a wish-fulfilling jewel. To my best knowledge, this has no forerunners among Chinese depictions. This specific work of art has been characterized as a “deluxe” example of a talisman, painted and calligraphed by hand, presumably made with a connoisseur in mind. Most people relied on cheap woodblock prints instead for their hakutaku needs. These were obviously perishable, so few of them survive, though two of the woodblocks used to make them, both from Togakushi, have been preserved. Notably, hakutaku talismans were employed during the cholera epidemic of 1858. Reportedly in Tokyo people placed them on their headrests before going to sleep. I sadly did not find any source explaining whether this was a conscious revival of the Tang custom discussed earlier, or if the similarity is entirely accidental. Hakutaku talismans were also utilized by travelers. this custom is documented in an Edo period book which can be considered an early example of a travel guide, Ryokō yōjinshū (旅行用心集; “Precautions for travelers”) by Yasumi Roan (八隅蘆菴). It was published in 1810 as part of what can be described as an early case of a domestic tourism boom resulting in the flourishing of travel literature. Much of the advice is surprisingly timeless, for example to abstain from leaving graffiti and stickers at landmarks such as temples and shrines, but also trees and sufficiently big rocks. I have to say the suggestion that a halberd is too heavy to carry around while on a trip is pretty solid too. Roan has many other great suggestions, but ultimately this is not an article about him, so they have to wait for another time. When it comes to the hakutaku, he states that travelers should equip themselves with images of this creature and the five great mountains of China (gogaku) to ward off spirits, but also wild animals and mundane accidents. Last thing which needs to be discussed here is that in addition to the apotropaic paintings, hakutaku was also sometimes portrayed in the form of a netsuke. However, such depictions are apparently not common.

A hakutaku netsuke from the British Museum (photo proided by my friend Li)

The modern reception of the hakutaku It remains unclear when apotropaic depictions of the hakutaku ceased to be made. It seems to me that it can be plausibly assumed it occurred in the Meiji period, but I have no solid evidence. However, the hakutaku was not entirely forgotten.

To my best knowledge, the single highest profile portrayal of a hakutaku in modern fiction is still Keine from Imperishable Night. What little spotlight she received paints an image remarkably close to the genuine accounts: as we learn from her bio, “she loves humans and always tries to help them” and she is pretty consistently portrayed as a staunch protector of the villagers and Mokou. The fact she’s not fully human doesn’t seem to be a mystery in-universe, and she is evidently accepted nonetheless. This doesn’t seem to be universally acknowledged in fanworks which is puzzling to me. There are dozens of yokai which are little more than boogeymen, but there are very few distinctly auspicious ones, and I prefer the canon approach of emphasizing that Keine and the village community mutually like each other. Keine’s role as a teacher presumably is meant to be a nod to the lecture about malign spirits the baize delivered to the Yellow Emperor. I am a huge fan of specifying the school she teaches at is a terakoya; whether ZUN was aware of it or not, hakutaku talismans and temple schools are both expressions of Edo popular culture, so the theme does more or less fit together. What little we learn about hakutaku in Touhou in general from Perfect Memento in Strict Sense also draws from historical sources. I will however note that as far as I can tell that revealing that a new ruler is going to be virtuous is a role assigned of various “auspicious beasts” like qilin, longma and so on in general rather than exclusively to the baize/hakutaku. There are also no legends about a hakutaku meeting with any Japanese rulers, even though most of Keine’s spellcards reference the imperial family (or attempts at overthrowing it; is she an anti-monarchist?). The rest of Keine's character seems to be ZUN’s invention. The only account of the hakutaku (well, baize’s) origin makes it clear the creature is a type of supernatural cattle, not a human, and there is obviously no such a thing as a “were-hakutaku”. I presume this was meant to highlight her human side and tie her more closely to the moon theme of Imperishable Night, though I think her character would still work perfectly fine without that. At the same time, I won’t deny I wouldn’t mind getting some more insights into Keine’s backstory in the future. Nothing major, just something similar to the Ran hints we just got in Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost. There is also no strong connection between the hakutaku and recording history, though you can probably make a case that as a mainstay of chronicles and encyclopedias it does have a distinctly historical theme. I personally like this innovation, and especially how it is described in PMiSS.Touhou aside, it’s worth mentioning that a resurgence in the interest in hakutaku occurred in the early months of the covid pandemic. This is an example of a broader surge in interest in various apotropaic disease-repelling mythical and folkloric figures in response to the rise of the novel coronavirus (as you might remember, the amabie fad in particular even managed to cross language barriers). It probably helped that a statue representing the hakutaku was rediscovered in the Tennō-ji in Osaka recently.

The Tennō-ji hakutaku (Asahi Shimbun; source contains more photos and a video. Reproduced here for educational purposes only) Some of the articles covering the brief hakutaku resurgence seemingly confuse it with the kutabe (kudan), but these are actually two separate creatures. The source of confusion is probably Shigeru Mizuki, who did depict kutabe as notably hakutaku-like, since he believed the it was a local adaptation of the standard hakutaku narrative.

Shigeru Mizuki’s kutabe (reproduced here for educational purposes only) Mizuki’s portrayal in turn influenced figures of kutabe made by local craftsmen from Takaoka in 2020. The English edition of Asahi Shimbun covered this in some more detail here, though ultimately it is beyond the scope of this article. As far as I know the connection, while plausible, does not permit full conflation, and in particular kutabe never attained the sort of religious significance hakutaku once had. Bibliography

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Donald Harper, 'Hakutaku hi kai zu' 白澤避怪図 (White Marsh Diagram to Repel Ominous Prodigies)

Donald Harper, Pictures of Baize / Hakutaku 白澤 (White Marsh): Ephemera and Popular Culture in Tang China and Edo Japan (not accessible online but there is a digital lecture version on youtube)

Jao Tsung-i, Postface to the Two Dunhuang Manuscript Fragments of the Baize jingguai tu 白澤精怪圖 (White Marsh’s Diagrams of Spectral Prodigies; P.2682, S.6261)

Richard E. Strassberg, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas

Kathryn Tanaka, Amabie as a Play in Kansai

Constantine N. Vaporis, Caveat Viator. Advice to Travelers in the Edo Period

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fabrication of a storm god: Susanoo, Taishakuten (Indra) and their histories

When I found this ask in my inbox recently, I initially admittedly wanted to only give a short, dismissive response. After all, the similarity between these two is completely superficial. And, truth to be told, it’s more a vague similarity between how they are presented as “storm gods” by questionable online sources than between their actual roles. However, I quickly realized that would not accomplish much. The best way to counter misconceptions is to show reality is more interesting - and in the case of complex figures with long histories, this requires time and effort. The response, like the recent Tamamo no Mae one, kept growing as a result, and evolved into a fully blown unplanned post. Under the cut, you will find a brief examination of the origin of the erroneous notion that Susanoo was ever understood a “storm god”, as well as a summary of his character character, the main deities linked to him in the Japanese “middle ages”, and finally his fate after the Meiji restoration. In the second half, I deal with the Japanese reception of Indra. While not actually related to Susanoo, he is nonetheless a complex deity worth exploring, even though it feels like he’s not particularly appreciated by hobbyists and his central role in medieval cosmology hardly gets acknowledged.

Victorian confabulations and Meiji mirages: the fabrication of a storm god

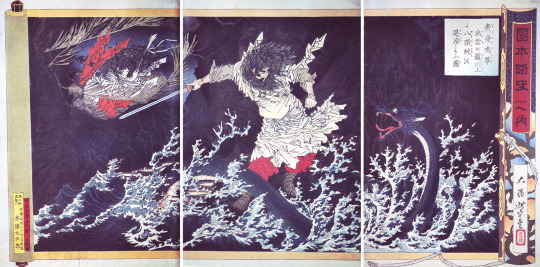

Susanoo vanquishing Yamata no Orochi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

Contrary to what you might have seen in numerous online sources of dubious quality, Susanoo is not a “storm god” (let alone a “thunder god” more specifically). Nothing to that effect shows up in standard points of reference like Encyclopedia of Shinto, and even Wikipedia despite arbitrarily putting him in the weather god category only musters a single 2000 paper which I’ve never seen cited in subsequent Susanoo research as “evidence” of a weather connection.

The most recent in depth treatments of Susanoo in English are a section of Bernard Faure’s monograph Rage and Ravage and David Weiss’ The God Susanoo and Korea in Japan’s Cultural Memory: Ancient Myths and Modern Empire. The former at no point makes any claims pertaining to the weather while discussing him. The latter notes the view that Susanoo was a “storm god” enjoyed some popularity in the late nineteenth century because of the influence of the now long abandoned school of “nature mythology”, in which deities are only ever representations of natural phenomena. This theory was originally formulated by Edward Burnett Tylor, who basically admitted no actual Japanese sources ever present him as a “storm god”, but that this character is nonetheless evident in his vibes (obviously not how he phrased it, but his study deserves no more dignified summary). Tylor’s nonsense was subsequently taken up by a certain Edmund Buckle, who randomly connected his forerunner’s oc with Indra because I guess all weather gods are basically interchangeable (there’s an interesting point to be made about how they’re the one group of male deities who are often treated in poor quality scholarship the way goddesses usually are). By 1899, the theory reached Japan, where it caused a prolonged academic debacle. However, it seems supporters of this view, much like in the west, were the followers of the long since abandoned notion of “nature mythology”. Among the theory’s opponents were researchers such as Masaharu Anesaki. As far as I can tell, it’s essentially irrelevant today.

The oldest available information about Susanoo’s actual character comes from the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. I don’t think that needs to be discussed here in detail. Even though I often overestimate other people’s familiarity with mythology I think it’s fair to say everyone with just a passing interest in Japan knows at least the basics of the myths about his conflict with his sister Amaterasu, his banishment, and subsequent victory over the serpent Yamata no Orochi. It will suffice to say the oldest recorded mythical image of him is that of an ambivalent deity, a heroic monster slayer on one hand, a transgressor and exile on the other. This polarity remains a core part of him for the rest of his history. The other early sources dealing with Susanoo are various fudoki, regional records. They indicate that in the eighth century he already was connected with diseases. Later on in the Heian period, he also came to be associated with purification. Or to be more precise - he came to be viewed as the archetypal target of purification, in a way. His misdeeds from classical mythology became examples of deeds requiring such ceremonies, performed variously by courtly ritual specialists like the Nakatomi clan, Buddhist clergy, or onmyōdō masters. He also functioned as a jinushi, a “landholder deity” of often ambivalent character tied to a specific location, and an araburugami, a “raging god” defined by causing havoc out of hubris (as opposed to malice).

Gozu Tennō and others: the network of medieval Susanoo Susanoo’s character developed through the Japanese “middle ages” in no small part through associations with other deities, typically caused by his incorporation into Buddhism.

A composite Susanoo-Gozu Tennō, as depicted by Sadahide Utagawa (Östasiatiska Museet, Stockholm)

The single most important figure he came to be linked with was by far Gozu Tennō, the “Bull-Headed Heavenly King”. While religious and literary texts present him as a deity from India, the guardian of the Jetavana monastery, and he was even furnished with an artificial Sanskrit name, Gomagriva Devaraja, his origin is actually uncertain. It’s possible he was inspired by a misreading of a passage from the travelog of the Chinese monk Faxian (c. 337-442). He visited Jetavana in the early fifth century, and reported that there was a statue of a bull next to the monastery’s door, before moving on to describing the supposed first image of the Buddha, which according to him was made from legendary “ox-head sandalwood” and impervious to fire. Confusion between these two passages might have led to the creation of an ox-headed deity. Other proposals are present in scholarship too, but ultimately the matter remains unclear. What is evident is that Susanoo and Gozu Tennō shared many similarities: the latter also was an archetypal “raging deity”, and he too was linked with pestilence. An argument can be made that he was the disease spirit par excellence in medieval Japan, in fact. When properly worshiped, he was supposed to protect the faithful from illnesses, as expected from a deity of this variety. They also shared an association with foreign lands: Gozu Tennō primarily with India, but also with China and Korea, while Susanoo just with Korea, due to a Nihon Shoki episode where he travels to the kingdom of Silla. Yet another point of connection is that both were simultaneously recognized as manifestations of Yakushi (the “medicine Buddha”). Therefore, it comes as no surprise that at the Gion shrine in Kyoto, and in many other locations across Japan, the two were identified fully.

However, the link was at times conceptualized differently than as interchangeability between the two. For instance, Kaneyoshi Ichijō’s treatise Kuji Kongen (公事根源; “Roots of Court Administration and Ceremonies”) Gozu Tennō is merely an “acolyte” (warawabe, 童部) of Susanoo. Granted, this author eventually came to view them as identical himself, which shows how fluid medieval theology could be.

A humorous depiction of Susanoo and Kushinadahime serving pieces of Yamata no Orochi prepared like grilled eel (Ōta Memorial Museum of Art; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The identification between Susanoo and Gozu Tennō also extended to their wives, respectively Kushinadahime and Harisaijo (波梨采女), as evident for example in the Shaku Nihongi. The latter was regarded as a daughter of the dragon king Sāgara. Things are made slightly awkward by the Nihon Shoki Sanso, where she is a manifestation of Yamata no Orochi (one of the multiple cases of putting a positive spin on the snake). Susanoo in the guise of Gozu Tennō thus effectively marries his nemesis. The marriage itself is a subject of a number of myths. According to Hoki Naiden (簠簋内伝), an onmyōdō manual, the “heavenly emperor” (Taishakuten, one would presume, based on information I’ll discuss later) de facto played the role of a matchmaker between Harisaijo and Gozu Tennō. When the latter was lamenting that due to his monstrous, yaksha-like form - he had the head of a bull - he will never find love, a bird sent by the celestial ruler informed him that it would be appropriate for him and Sāgara’s daughter to get married. This suggestion then evidently works out just fine, and the couple subsequently have eight children, the Hachiōji (八王子, “eight princes”) over the course of thirty seven years.

Hyōbi (wikimedia commons)

There are multiple slightly divergent traditions about the identities of the children. The most notable variable is that a goddess named Jadokkeshin (蛇毒気神; also read Dadokuke no kami; “deity of poisonous snake breath”) sometimes appears among them, sometimes is treated as an independent deity serving Gozu Tennō, and sometimes takes the role of his spouse (in at least one case with Harisaijo quite literally relegated to the role of his ex). She is also identified with the astral deity Hyōbi (豹尾, “leopard tail”) and by extension with Ketu.

Another figure who was closely linked with Susanoo in the middle ages was Matarajin. This tradition was associated with Gakuen-ji. In a local legend, Susanoo started to be called Matarajin after being buried underneath it. I won’t dwell much on Matarajin here since I already wrote a lot about him, and will write even more in the near future, so it will suffice to say the two share a connection to diseases. In Matarajin’s case it is the most pronounced in the “ox festival” still held in modern times at Kōryū-ji.

Shinra Myōjin (wikimedia commons)

Connections between Susanoo and Matarajin’s fellow Tendai old man disease-related deities Sekizan Myōjin and Shinra Myōjin are documented too. Bernard Faure argues that in fact it was Shinra Myōjin who first developed such an association, and it was only transferred to Matarajin as well because of the numerous analogies between them.

A distinct tradition regarding Susanoo developed in the theology of Ise (“Ryōbu shintō”), which as expected was Amaterasu-centric (but also Dainichi-centric!). He came to be linked with Mara and Devadatta as a representation of “fundamental ignorance”, with the conflict between him and Amaterasy gaining an additional Buddhist dimension. At the same time, in the noh play Dairokuten (第六天), which deals with Jōkei’s pilgrimage to Ise, Susanoo appears to protect this monk from Mara. Evidently, in this context Susanoo and Amaterasu are hardly opposed to each other, seeing as the former de facto intervenes on behalf of the latter.

While the notion of rivalry between the siblings obviously did not vanish in the middle ages, and in fact new myths about it started to circulate (in one Matarajin assists Susanoo), it can be argued that it was ultimately the new conflict between Amaterasu and Mara that was central to many medieval theologies. While she and Susanoo could be portrayed as antagonistic, there is a case to be made that there were more similarities between medieval ideas about them than there were differences. That was not meant to last, though.

Later developments

The tradition of associating Susanoo with assorted medieval deities first came under criticism in the eighteenth century. Sadakage Amano, an early proponent of kokugaku ("national learning", an early Japanese nationalist ideology) ideas, wrote a treatise dealing with this matter, Gozu Tennō Ben (牛頭天王辨, “Clarification on Gozu Tennō”). Its core premise is that monks and shrine priests alike are deceptively trying to present “foreign” deities as identical with “native” ones. This point was further developed in the nineteenth century by another kokugaku big name, Atsutane Hirata.

Hirata's self portrait (wikimedia commons)

He reaffirmed that presenting Susanoo and Gozu Tennō as related deities was a nefarious plot, and blamed Kibi no Makibi for starting it. He argued that Makibi spent too much time in China and as a result forsake a pristinely Japanese way of thinking (whatever that wouldn't entail). As a result, when he heard the legend of ox-head sandalwood, which was believed to grow on the mythical continent Uttarakuru and cure diseases, he turned it into a deity, who he subsequently brought to Japan. Then he identified him with Susanoo to increase his prestige.

Was that the historical truth? Kibi no Makibi was an envoy to China and spent around 20 years on the mainland, that much is undeniable. However, the only connection between him and Gozu Tennō I was able to track down is a local legend pertaining to Mount Hiromine in which he meets this deity in a dream, though.

Ultimately like most of Hirata’s writing, his theory consists virtually entirely of confabulations, mostly motivated by extreme levels of xenophobia. Rather ironic for a movement which originally largely developed among the most hardcore neo-Confucian thinkers in Japan. Granted, that’s hardly the only baffling thing about them. The best way to understand what was going on in the heads of kokugaku proponents is to recall how contemporary marble bust profile pic “the west has fallen” trads or Bible literalist creationists function, and adjust that image for the specifics of the Edo period.

Still, kokugaku theories, nonsensical as they were, kept developing, and finally gained government support after the Meiji revolution. In 1868, the Council of State proclaimed that shrines can no longer use “inappropriate” names to refer to their deities. Gozu Tennō was the only example brought up directly, in part possibly because with the reestablishment of the power of the emperor and the rise of the imperial cult it was viewed as suspicious that a deity unrelated to the imperial court had the moniker of tennō (written with different signs, though). The edict also contains a blanket ban on any name with the element gongen. As a result of the new policies numerous locations had to be renamed, and for the most part the history of Gozu Tennō came to an end. He and his peers eventually came back into the spotlight in the second half of the twentieth century as subjects of scholarly inquiries, and the field of study of medieval and early modern Japanese religions is now booming, with entire monographs and articles published in multiple languages each year, but that’s another story.

The history of Susanoo obviously did not end in the 1860s, though. What followed was probably the single darkest page in it, an era of intense efforts to make him identical with Dangun, the legendary founder of Korea. The goal was explicitly to justify Japanese colonial control over Korea through faux-spiritual means. Since Japanese colonial domination of Korea is a relatively recent and deeply serious historical issue compared to what I cover most of the time, I feel it would be inappropriate to deal with it in the same article as medieval literature which ultimately lacks much of a tangible impact on the modern world, so I hope you won’t mind I don’t go deeper into the detail here.

With the matter of Susanoo now settled, let’s move on to Indra. The two were never associated with each other, but the latter developed an equally vibrant network of roles and associated deities around him as Susanoo after being transmitted to Japan.

From Indra to Taishakuten

A typical Hindu depiction of thousand-eyed Indra (wikimedia commons)

Indra has a long and complex history, so long he is in fact attested a handful of times in bronze age cuneiform already as one of the notoriously mysterious non-Hurrian Mitanni deities (sic), invoked as personal deities of the royal house in a lengthy treaty oath. This makes him one of the very few “bridges” between my two major normally disconnected interests (the “cuneiform world” on one hand, and East Asian religions and art on the other).

The biggest early text corpus dealing with Indra are the Vedas, where he is the single most frequently mentioned deity, with quite literally hundreds of hymns praising him. Naturally, he remained a part of the history of Hinduism later on, and today he is still well known thanks to his role in popular epics like Ramayana. His relevance is not limited to this system of beliefs alone, though. He has a small (negative) role in the Avesta (see here), and he was embraced by various schools of Buddhism across much of Asia.

In early Buddhism, the prestige of Indra was not particularly great. This obviously reflects the fact that the formative years of Buddhism were also a period of Indra’s relative decline as an actively worshiped god back at home at the expense of deities central in contemporary Hinduism like Vishnu and Shiva. However, he surprisingly regained some of his original prestige thanks to developments which occurred outside of India. This is well documented in East Asia in particular. I’ll only cover his Japanese reception here - therefore, through most of the rest of the article I will use his Japanese name, Taishakuten (帝釈天), accordingly. Buddhism emphasizes not Indra’s warlike side and his battles with asuras, let alone a connection with the weather, but rather his role as a heavenly ruler. He keeps epithets related to his 1000 eyes, but to the best of my knowledge this is not really reflected in Buddhist art, especially not in Japan. Another role retained by him in Buddhism is that of a directional deity, the protector of the east.

Something that’s worth highlighting is that asuras in general just aren’t that big of a deal in Japanese Buddhism. Outside of enumerations of non-human sentient beings, only Rahu and Ketu have a substantial role, and that’s more because they’re astral deities rather than because they’re asuras. Otherwise the entire category is about as opaque as mahoragas (when you look up “mahoraga” online 99% results are a Jujutsu Kaisen character, as it turns out, which speaks volumes about their general obscurity) and the like. Hard to make opposition to them the focus of a major deity when even gandharvas have a bigger role to play.

I can only think of a handful of major references to battles between Taishakuten and asuras in Japanese literature: an offhand comment in Heike Monogatari (courtesy of Kenreimon-in), a passage from the Taiheiki where Jōkei (who you already met earlier in this article) has the privilege to watch the parties involved reenact the conflict for his benefit, and a myth cited by Annen with no source provided, possibly invented by him. The innovation is that Marici (Marishiten) is a major combatant on the side of the devas, something with no parallel in any other source, whether Buddhist or Hindu. Rahu is singled out among the asuras as an enemy of Taishakuten, but that’s hardly unparalleled.

The conventional image of Taishakuten

A conventional depiction of Taishakuten (wikimedia commons)

For the average Japanese person through much of the country’s history, the most frequent exposure to Taishakuten were standardized oath formulas (kishōmon). These followed a strict hierarchy of deities: Taishakuten, Bonten (Brahma) and the four heavenly kings first, then king Enma, Godo Daishin (Wudao Dashen), Taizan Fukun and other underworld officials (sometimes assisted by astral figures), then kami and representations of Buddhas tied to specific localities (for example the great Buddha of Tōdai-ji), and sometimes various religiously significant historical figures like prince Shotoku or Buddhist patriarchs. Obviously, Taishakuten’s elevated position reflects his role as a heavenly ruler - the “heavenly emperor”, tentei (天帝).

The residence of Taishakuten is the heaven of the thirty three devas (忉利天, Tōriten, a calque from Sanskrit Trāyastriṃśa). It is located on Mount Sumeru, the center of the world according to Buddhist cosmology. Sources from the Heian period indicate the existence of a belief Taishakuten’s heaven is unique in that women could be reborn in it after death without first reincarnating as men. This distinction was otherwise only attributed to the pure land of Maitreya. Note it was not Taishakuten himself who was responsible for guaranteeing that, though, but rather the bodhisattva Fugen, who was particularly popular among Heian court ladies.

Karai Tenjin (wikimedia commons)

Taishakuiten’s major position in the Buddhist-influenced cosmos is also evident in literary compositions focused on other deities. For example, in the Dōken Shōnin Meidoki (道賢上人冥途記, “Record of Dōken Shōnin’s Experience of the Other World”), a version of the legend of Michizane, his revenge is supported by Taishakuten, who gives him a new name, Nihon Dajō Itoku Ten (日本太政威徳天). This is meant to show his banishment was a religious transgression, and we also learn that the emperor responsible for it, Daigo, fell into hell as a result. However, esoteric Buddhism is also credited with calming Michizane down - as he explains himself, “bodhisattvas (...) were there, and they enthusiastically propagated the esoteric teachings. Because I liked these teachings very much, one-tenth of my deeply seated enmity from my past was reduced.” This obviously goes against the more common legend where being enshrined pacifies Michizabe entirely. In the Dōken version he announces that the enshrined deity, who he calls Karai Taiki Dokuō (火雷大気毒王; “King of Fire-Thunder and Poisonous Air”), is merely his messenger #3 (#1 and #2 are not mentioned).

The closest thing I can think of to Taishakuten being associated with the weather in Japanese sources occurs in a version of the Michizane legend, too: in another variant, Michizane states it was Taishakuten alone who permitted him to enact his vengeance and entrusted him with commanding 105000 thunder gods (in the Dōken Shōnin Meidoki there are 168000 attendants instead, “poisonous dragons, evil demons, deities of water and fire, thunder and lightning, the director of the wind, the master of the rain, and other poisonous, harmful, and evil deities”) and causing disasters.

From emperor to heaven to controller of fate

Due to his prominent cosmological role Taishakuten is also described in many sources as a controller of fate responsible for determining the lifespans of living beings. Sometimes, in this capacity he basically overlaps with king Enma - for example, Shishi Yaloan, a Buddhist encyclopedia from the eleventh century, states that he also possesses a mirror in which he can check on his subjects. A local tradition from Tateyama states that he lives on the Taishaku Peak of Mt. Tate, simultaneously regarded as an entrance to Buddhist hell. However, while Enma and the other kings of hell generally stay there, Taishakuten takes a more proactive role, seeking information about the good and bad deeds of the living. Initially, it was believed that a survey of the whole world was conducted on his behalf by the four heavenly kings, but by the tenth century, a belief that he performs it himself every four months himself developed.

The famously unconventional depiction of Taishakuten from Shibamata Taishakuten, still distributed today in the form of ofuda (wikimedia commons)

In the Edo period, Taishakuten as a controller of fate developed a connection with deities associated with the tradition of kōshin nights. In this context he became the deity the three worms living in every person’s body report their good and bad deeds to. Temples associated with him, like Shibamata Taishakuten (famous among other things for its unconventional images of the eponymous deity), were historically a popular destination for pilgrimages tied to kōshin celebrations.

While the fate connection ultimately came to the forefront in Japan, it would be unfair to say it entirely superseded the original heavenly role. As a matter of fact, it was the fact that Taishakuten was a “heavenly emperor” (tentei) that made him such a good fit for kōshin.

The elusive "emissary of Taishaku" As early as in the Muromachi period, yet another deity came to be viewed as responsible for Taishakuten's survey of the world in a variant tradition: one of the so-called “ambulatory deities” (遊行神, yugyōjin; “ambulatory” as in “wandering”, not in the medical sense) , Ten’ichi(jin) (天一神; also read Nakagami), literally “the first deity of heaven”. He was regarded as a “vassal” of Taishakuten and the commander of the Twelve Heavenly Generals. Each of his cyclical surveys of the world lasted 44 days (four times five days for each of the main directions and then four times six for the intermediate ones). That was followed by sixteen days during which he reported the vices and virtues he recorded to Taishakuten in heaven, with his own underling Nichiyū(jin) (日遊神; “playing sun deity”) descending to earth instead. During Tenichi’s absence, which started with a day referred to as Ten’ichi tenjō (天一天上), directional taboos pertaining to various astral deities, which normally had to be countered with a practice known as “changing directions” (方違え, katatagae), did not apply.

Taishaku Shisha (top right) and his peers accompanying Dakiniten (wikimedia commons)

Another interesting thing about Ten’ichi is that he was identified with an elusive deity known simply as Taishaku Shisha (帝釈使者), literally “emissary of Taishaku”. At first glance this doesn’t really sound interesting - after all, Taishaku Shisha’s name sounds exactly like what Ten’ichi does - but completely unexpectedly, the former actually belongs to the entourage of Dakiniten. His attributes make him resemble officials of the underworld, though he is never portrayed as menacing, always as benign, and his duty is to report the good and bad deeds to his superiors, much like Ten’ichi does. He additionally functions as a god of wisdom, which according to Bernard Faure might reflect Dakiniten’s link to the bodhisattva Monju, famous due to an association with this concept.

Curiously, while Taishaku Shisha is at least nominally a member of a group of four “acolytes” of Dakiniten alongside Tennyoshi (天女子; “heavenly maiden”; holds a bow), Shakunyoshi (赤女子; “red maiden”; holds a halberd and a “seduction jewel”, aikei-gyoku, 愛敬玉) and Kokunyoshi (黒女子; “black maiden”; holds a sword and a black jewel), he is sometimes described as de facto separate from them. Perhaps the fact his very name links him with another deity has something to do with that. Also, he is absent from the origin myth of the three maidens, who according to Hoki Naiden flew to Japan from India. According to Bernard Faure, it is possible his roles overlapped in part with Dakiniten’s own emissaries, the tengu Tonyūgyō (頓遊行; brings happiness) and Suyochisō (須臾馳走; brings longevity).

Dakiniten, “demon kings” and Amaterasu: the network of Taishakuten

Dakiniten (wikimedia commons)

Taishakuten’s connection with Dakiniten goes beyond the figure of Taishaku Shisa. The Mizōukyo (未曽有經) contains a myth according to which a fox once tricked Indra into accepting the animal as his master is recorded. It serves as an explanation for the notably fox-like Dakiniten’s elevated role in the royal ascension rite devised by Shingon priests (it was still performed in the 19th century, emperor Meiji was the first to abstain from it). In folk beliefs Taishakuten was also sometimes assigned the role of the “master of the foxes”, which normally belonged to her instead.

The link to these animals according to Bernard Faure might have reflected a more ambivalent perception of Taishakuten than usually expected. The other possible piece of evidence in favor of this interpretation is a poem which proclaims that he and Tsuno Daishi, the demonic manifestation of Ryōgen, look “like brothers”. The latter is a complex figure, but it will suffice to say here that historically he was sometimes perceived as a “demon king” (魔王, maō). On the other hand, the original holder of this title, the “Demon King of the Sixth Heaven” (in other words, Mara) was said to offer his blood to Taishakuten on “blood-shunning days” (地幅, chi-imbi). In practical terms, this meant a religious prohibition on the drawing of blood, acupuncture and moxibustion on a specific day, different each month. I need to stress here that even though figures such as Dakiniten and the “demon kings” obviously originated in the realm of demonology - respectively as a flesh-eating, vital essence-stealing demon and as the tempter of the Buddha - they eventually developed much more complex and nuanced characters. Therefore, it is not unexpected major deities appear in association with them. In the middle ages, even Amaterasu was frequently linked with them. Funnily enough, in contrast with Susanoo Amaterasu does have a connection to Taishakuten as well. Tenshō Daijin Kuketsu (天照大神口決; “Oral Transmission.Pertaining to the Great Goddess Amaterasu”) from 1328 states that she corresponds to him - but also to Bonten, Shōten (Ganesha), the kushōjin (倶生神; these would take a bit to explain), king Enma and Godō Daijin. Granted, another roughly contemporary treatise, Reikiki, instead proclaims Taishakuten, the “heavenly emperor” (tentei; just like in the later kōshin tradition) the “kami-body” of Toyouke, the outer shrine Ise deity. However, these matters ultimately go beyond the scope of this response. Stay tuned for my article about medieval Amaterasu to find out more!

Bibliography

Ryūichi Abe, Women and the “Heike Nōkyō”: the Dragon Princess, the Jewel and the Buddha

Bernard Faure, The Fluid Pantheon (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 1)

Idem, Protectors and Predators (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 2)

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Gerald Gromer, A Year in Seventeenth-Century Kyoto. Edo-Period Writings on Annual Ceremonies, Festivals, and Customs

Takuya Hino, The Daoist Facet of Kinpusen and Sugawara no Michizane Worship in the Dōken Shōnin Meidoki: A Translation of the Dōken Shōnin Meidoki

Nobumi Iyanaga, Medieval Shintō as a Form of 'Japanese Hinduism': An Attempt at Understanding Early Medieval Shintō

William Lindsey, Religion and the Good Life: Motivation, Myth, and Metaphor in a Tokugawa Female Lifestyle Guide

Fabio Rambelli, Before the First Buddha: Medieval Japanese Cosmogony and the Quest for the Primeval Kami

Hiroo Satō, Wrathful Deities and Saving Deities in: Fabio Rambelli and Mark Teeuwen (eds.), Buddhas and Kami in Japan. Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm

Idem, The Emergence of Shinkoku (Land of the Gods) Ideology in Japan in: Henk Blezer and Mark Teeuwen (eds.), Challenging Paradigms. Buddhism and Nativism: Framing Identity Discourse in Buddhist Environments

David Weiss, The God Susanoo and Korea in Japan’s Cultural Memory: Ancient Myths and Modern Empire.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

im starting a foundation to introduce underprivileged children to forbidden techniques

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm so fascinated by languages with different levels of formality built in because it immediately introduces such complex social dynamics. The social distance between people is palpable when it's built right into the language, in a way it's not really palpable in English.

So for example. I speak Spanish, and i was taught to address everyone formally unless specifically invited otherwise. People explained to me that "usted" was formal, for use with strangers, bosses, and other people you respect or are distant from, while "tú" is used most often between family and good friends.

That's pretty straightforward, but it gets interesting when you see people using "tú" as a form of address for flirting with strangers, or for picking a fight or intimidating someone. In other languages I've sometimes heard people switch to formal address with partners, friends or family to show when they are upset. That's just so interesting! You're indicating social and emotional space and hierarchy just in the words you choose to address the other person as "you"!!

Not to mention the "what form of address should I use for you...?" conversation which, idk how other people feel about it, but to me it always felt awkward as heck, like a DTR but with someone you're only just becoming comfortable with. "You can use tú with me" always felt... Weirdly intimate? Like, i am comfortable around you, i consider you a friend. Like what a vulnerable thing to say to a person. (That's probably also just a function of how i was strictly told to use formal address when i was learning. Maybe others don't feel so weird about it?)

And if you aren't going to have a conversation about it and you're just going to switch, how do you know when? If you switch too soon it might feel overly familiar and pushy but if you don't switch soon enough you might seem cold??? It's so interesting.

Anyway. As an English-speaking American (even if i can speak a bit of Spanish), i feel like i just don't have a sense for social distance and hierarchy, really, simply because there isn't really language for it in my mother tongue. The fact that others can be keenly aware of that all the time just because they have words to describe it blows my mind!

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

the motel room, or: on datedness

I.

Often I find myself nostalgic for things that haven't disappeared yet. This feeling is enhanced by the strange conviction that once I stop looking at these things, I will never see them again, that I am living in the last moment of looking. This is sense is strongest for me in the interiors of buildings perhaps because, like items of clothing, they are of a fashionable nature, in other words, more impermanent than they probably should be.

As I get older, to stumble on something truly dated, once a drag, is now a gift. After over a decade of real estate aggregation and the havoc it's wreaked on how we as a society perceive and decorate houses, if you're going to Zillow to search for the dated (which used to be like shooting fish in a barrel), you'll be searching aimlessly, for hours, to increasingly no avail, even with all the filters engaged. (The only way to get around this is locational knowledge of datedness gleaned from the real world.) If you try to find images of the dated elsewhere on the internet, you will find that the search is not intuitive. In this day and age, you cannot simply Google "80s hotel room" anymore, what with the disintegration of the search engine ecosystem and the AI generated nonsense and the algorithmic preference for something popular (the same specific images collected over and over again on social media), recent, and usually a derivative of the original search query (in this case, finding material along the lines of r/nostalgia or the Backrooms.)

To find what one is looking for online, one must game the search engine with filters that only show content predating 2021, or, even better, use existing resources (or those previously discovered) both online and in print. In the physical world of interiors, to find what one is looking for one must also now lurk around obscure places, and often outside the realm of the domestic which is so beholden to and cursed by the churn of fashion and the logic of speculation. Our open world is rapidly closing, while, paradoxically, remaining ostensibly open. It's true, I can open Zillow. I can still search. In the curated, aggregated realm, it is becoming harder and harder to find, and ultimately, to look.

But what if, despite all these changes, datedness was never really searchable? This is a strange symmetry, one could say an obscurity, between interiors and online. It is perhaps unintentional, and it lurks in the places where searching doesn't work, one because no one is searching there, or two, because an aesthetic, for all our cataloguing, curation, aggregation, hoarding, is not inherently indexable and even if it was, there are vasts swaths of the internet and the world that are not categorized via certain - or any - parameters. The internet curator's job is to find them and aggregate them, but it becomes harder and harder to do. They can only be stumbled upon or known in an outside, offline, historical or situational way. If to index, to aggregate, is, or at least was for the last 30 years, to profit (whether monetarily or in likes), then to be dated, in many respects, is the aesthetic manifestation of barely breaking even. Of not starting, preserving, or reinventing but just doing a job.

We see this online as well. While the old-web Geocities look and later Blingee MySpace-era swag have become aestheticized and fetishized, a kind of naive art for a naive time, a great many old websites have not received the same treatment. These are no less naive but they are harder to repackage or commodify because they are simple and boring. They are not "core" enough.

As with interiors, web datedness can be found in part or as a whole. For example, sites like Imgur or Reddit are not in and of themselves dated but they are full of remnants, of 15-year old posts and their "you, sir, have won the internet" vernacular that certainly are. Other websites are dated because they were made a long time ago by and for a clientele that doesn't have a need or the skill to update (we see this often with Web 2.0 e-commerce sites that figured out how to do a basic mobile page and reckoned it was enough). The next language of datedness, like the all-white landlord-special interior, is the default, clean Squarespace restaurant page, a landing space that's the digital equivalent of a flyer, rarely gleaned unless someone needs a menu, has a food allergy or if information about the place is not available immediately from Google Maps. I say this only to maintain that there is a continuity in practices between the on- and off-line world beyond what we would immediately assume, and that we cannot blame everything on algorithms.

But now you may ask, what is, exactly, datedness? Having spent two days in a distinctly dated hotel room, I've decided to sit in utter boredom with the numinous past and try and pin it down.

II.

I am in an obscure place. I am in Saint-Georges, Quebec, Canada, on assignment. I am staying at a specific motel, the Voyageur. By my estimation the hotel was originally built in the late seventies and I'd be shocked if it was older than 1989. The hotel exterior was remodeled sometime in the 2000s with EIFS cladding and beige paint. Above is a picture of my room, which, forgive me, is in the process of being inhabited. American (and to a lesser extent Canadian) hotel rooms are some of the most churned through, renovated spaces in the world, and it's pretty rare, unless you're staying in either very small towns or are forced by economic necessity to stay at real holes in the wall, to find ones from this era. The last real hitter for me was a 90s Day's Inn in the meme-famous Breezewood, PA during the pandemic.

At first my reaction to seeing the room was cautionary. It was the last room in town, and certainly compared to other options, probably not the world's first choice. However, after staying in real, genuine European shitholes covering professional cycling I've become a class-A connoisseur of bad rooms. This one was definitively three stars. A mutter of "okay time to do a quick look through." But upon further inspection (post-bedbug paranoia) I came to the realization that maybe the always-new brainrot I'd been so critical of had seeped a teeny bit into my own subconscious and here I was snubbing my nose at a blessing in disguise. The room is not a bad room, nor is it unclean. It's just old. It's dated. We are sentimental about interiors like this now because they are disappearing, but they are for my parents what 2005 beige-core is for me and what 2010s greige will become for the generation after. When I'm writing about datedness, I'm writing in general using a previous era's examples because datedness, by its very nature, is a transitional status. Its end state is the mixed emotion of seeing things for what they are yet still appreciating them, expressed here.

Datedness is the period between vintage and contemporary. It is the sentiment between quotidian and subpar. It is uncurated and preserved only by way of inertia, not initiative. It gives us a specific feeling we don't necessarily like, one that is deliberately evoked in the media subcultures surrounding so-called "liminal" spaces: the fuguelike feeling of being spatially trapped in a time while our real time is passing. Datedness in the real world is not a curated experience, it is only what was. It is different from nostalgia because it is not deliberately remembered, yearned for or attached to sweetness. Instead, it is somehow annoying. It is like stumbling into the world of adults as a child, but now you're the adult and the child in you is disappointed. (The real child-you forgot a dull hotel room the moment something more interesting came along.) An image of my father puts his car keys on the table, looks around and says, "It'll do." We have an intolerance for datedness because it is the realization of what sufficed. Sufficiency in many ways implies lack.

However, for all its datedness, many, if not all, of the things in this room will never be seen again if the room is renovated. They will become unpurchaseable and extinct. Things like the bizarrely-patterned linoleum tile in the shower, the hose connecting to the specific faucet of the once-luxurious (or at least middling) jacuzzi tub whose jets haven't been exercised since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The wide berth of the tank on the toilet. There is nothing, really, worth saving about these things. Even the most sentimental among us wouldn't dare argue that the items and finishes in this room are particularly important from a design or historical standpoint. Not everything old has a patina. They're too cheaply made to salvage. Plastic tile. Bowed plywood. The image-artifacts of these rooms, gussied up for Booking dot com, will also, inevitably disappear, relegated to the dustheap of web caches and comments that say "it was ok kinda expensive but close to twon (sic)." You wouldn't be able to find them anyway unless you were looking for a room.

One does, of course, recognize a little bit of design in what's here. Signifiers of an era. The wood-veneer of the late 70s giving way to the pastel overtones of the 80s. Perhaps even a slow 90s. The all-in-one vanity floating above the floor, a modernist basement bathroom hallmark. White walls as a sign of cleanliness. Gestures, in the curved lines of the nightstands, towards postmodernity. Metallic lamp bases with wide-brimmed shades, a whisper of glamor. A kind of scalloped aura to the club chairs. The color teal mediated through hundreds if not thousands of shoes. Yellowing plastic, including the strips of "molding" that visually tie floor to wall. These are remnants (or are they intuitions?) of so many movements and micromovements, none of them definite enough to point to the influence of a single designer, hell, even of a single decade, just strands of past-ness accumulated into one thread, which is cheapness. Continuity exists in the materials only because everything was purchased as a set from a wholesale catalog.

In some way a hotel is supposed to be placeless. Anonymous. Everything tries to be that way now, even houses. Perhaps because we don't like the way we spy on ourselves and lease our images out to the world so we crave the specificity of hotel anonymity, of someplace we move through on our way to bigger, better or at least different things. The hotel was designed to be frictionless but because it is in a little town, it sees little use and because it sees little use, there are elements that can last far longer than they were intended and which inadvertently cause friction. (The janky door unlocks with a key. The shower hose keeps coming out of the faucet. It's deeply annoying.)

Lack of wear and lack of funds only keep them that way. Not even the paper goods of the eighties have been exhausted yet. Datedness is not a choice but an inevitability. Because it is not a choice, it is not advertised except in a utilitarian sense. It is kept subtle on the hotel websites, out of shame. Because it does not subscribe to an advertiser's economy of the now, of the curated type rather than the "here is my service" type, it disappears into the folds of the earth and cannot be searched for in the way "design" can. It can only be discovered by accident.

When I look at all of these objects and things, I do so knowing I will never see them again, at least not all here together like this, as a cohesive whole assembled for a specific purpose. I don't think I'll ever have reason to come back to this town or this place, which has given me an unexpected experience of being peevish in my father's time. Whenever I end up in a place like this, where all is as it was, I get the sense that it will take a very long time for others to experience this sensation again with the things my generation has made. The machinations of fashion work rapaciously to make sure that nothing is ever old, not people, not rooms, not items, not furniture, not fabrics, not even design, that old matron who loves to wax poetic about futurity and timelessness. The plastic-veneered particleboard used here is now the bedrock of countless landfills. Eventually it will become the chemical-laced soil upon which we build our condos. It is possible that we are standing now at the very last frontier of our prior datedness. The next one has not yet elided. It's a special place. Spend a night. Take pictures.

If you like this post and want more like it, support McMansion Hell on Patreon for as little as $1/month for access to great bonus content including a discord server, extra posts, and livestreams.

Not into recurring payments? Try the tip jar! Student loans just started back up!

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Men's beauty practices in imperial China

English added by me :)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

so when i was taught about kafka in english class (we read the metamorphosis, as one does in high school english), we covered his struggles with chronic mental and physical illnesses, and his fraught relationship with his father especially. and yes! these are vital components to understanding where kafka was coming from. as a teenager, i really liked his writing, but i also empathized with my classmates who found his writing whiny and melancholy.

i decided to revisit kafka, and have found that i still adore his prose. importantly, however, as an anarchist now deeply aware of history, i am comfortable saying that eradicating kafka’s jewishness and politics from analysis of his work is a mistake, and most certainly why some people find his writing morose.

a complaint i heard about the metamorphosis was how jarring and unrealistic it felt that EVERYONE hated mr. samsa. if your only context for kafka’s life was how abusive his dad was, it would seem to the reader that he was applying his trauma to the rest of the world, kind of projecting that pain outward onto everyone else. and ya know, as a teen being abused, that was a useful read for me. but when you consider that kafka was a jewish man in prague in 1914, his view on the world and how he thought the world interpreted him makes perfect sense. kafka was also living at a time when the police state was being established, when nations were just starting to be a thing, immediately before WWI, etc etc etc- and the man wrote about it! reading The Trial now, i cannot disentangle my enjoyment of this book from the real like shit that was happening around the author

idk. we talk about kafka as being sad, or being kind, or being a bug (lol) but i think we do him a disservice when we don’t also address him as a sharply political person

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

jeff vandermeer’s annotations for annihilation…… he really does Get It

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

i saw the trailer for the new feel-good “anti-racist” US war movie about the carpet bombing of North Korea and started writing up something for this blog, partially inspired by the absolute shit storm i got for sharing that post i made with pictures of everyday life outside pyongyang

and then i gave up, because what’s the point? westerners can’t even handle a single picture of a north korean not looking miserable without screaming propaganda

meanwhile, there are no stories about the horrors of life in the ‘hermit kingdom’ that are deemed too outlandish to be believable. i can’t remember who said it, but it’s like the entire country has taken up permanent residence in the western imaginary as some silly little cartoon villain, where the leaders of the country does evil things for no discernible reason. they’re just silly and evil like that, and the citizens, of course, are silly, too. silly and brainwashed.

i watched a video recently of a tourists visiting an auto dealership in pyongyang, and the entire time he was just gawking at the employees and costumers, shoving his phone in their face, and confidently explaining to his youtube audience that everyone he’s interacting with are actually actors.

what level of dehumanization do you have to reach for that thought to even cross your mind? to think that the people you see before you are actors? that entire cities and shops are erected with to sole purpose that you, a western, will see them and be impressed?

what frustrates me the most is the casual cruelty that seeps into any mention of north korea, no matter how small. if north koreans are not being evil, they’re being silly.

a north korean newspaper reports that a group of archeologists in pyongyang have discovered an old rock carving with the words ‘unicorn lair’ (mistranslated), and the western press reports that north koreans now believe in unicorns.

a tourist at a hotel in hamhung is told by the receptionist to be careful at the beach: the waves can get high. that day the tourists goes to the beach, and there are no waves. she retells the story to her instagram followers, explaining that the poor woman at the hotel could never have seen real waves before because north koreans are probably never allowed to travel.

she adds a little teary-eyed emoji.

one of the cities i included in the post was sariwon, a densely populated city to the south of pyongyang. below are some pictures from its “folk customs street”, which was built to showcase old korean traditions and customs

here’s all wikipedia has to say about it

Built to display an ideal picture of ancient Korea, it includes buildings in the “historical style” and a collection of ancient Korean cannons. Although it is considered an inaccurate romanticized recreation of an ancient Korean street, it is frequently used as a destination for foreigners on official government tours. Many older style Korean buildings exist in the city.

it’s just north koreans being silly again. there’s no mention of what might motivate them to build a street like that — why the preservation of old customs, culture and architecture might somehow be important for the city

could it perhaps have something to do with how the U.S. air force dropped 635,000 tons of bombs, including 32,557 tons of napalm, over the korean peninsula during the war? the carpet bombings, which are now the topic of an upcoming hollywood movie about overcoming racism through warcrimes, destroyed an estimate of 85% of all buildings in north korea. some cities were entirely wiped off the map.

in sariwon they missed a few buildings, but not many — after an intense firebombing campaign the U.S. military estimated the destruction of sariwon to be at 95%.

none of this is mentioned on the wikipedia page for sariwon.

we destroyed entire cities. memory-holed the entire thing, called it the forgotten war. and now, 70 years later, we’re convincing ourselves that the people living in the ruins are actors.

and somehow the north koreans are the brainwashed ones

45K notes

·

View notes