Text

A Discourse on Ranch

Let’s begin with language. The English words salad and sauce both come from the same Latin root, the word sal meaning “salt”. In Latin, salsa means “salty” and salata means “salted”. Later, in Latin, “salsa” became the word for a liquid or semi-liquid food, containing salt, which is used to bring flavor to other foods. The famous garum salty fish sauce of the ancient Romans is a perfect, early example of the concept. “Salsa” entered some Latin-based languages intact (in Italian and Spanish). A different Roman dish, herba salata or “salted greens”, became the French abbreviation herbes salade and then just salade in roughly the 14th century. At about the same time in the same place, the French converted the Latin word salsa into a new French word, sauce. The point here is that salads and sauces are closely related, and come to us via the Roman Empire and particularly the French part of it. And, if you think of it, the “dressing” you put on a salad is really a sauce; it only becomes called “dressing” in English when you put it on a salad. Here, we will use “dressing” and “sauce” more or less interchangeably. But more on that later. Salads have varied in popularity over the years. At some points in history, raw salads were seen as dangerous as they still are in places where water is unsafe or raw manure is used to fertilize fields. Cooking vegetables neutralizes dangerous bacteria, after all. At other times, however, the virtues of raw-vegetable salads- especially ones based on lettuce leaves- were celebrated for being healthful and enjoyable.

"Lettuce" from the Tacunium Sanitatis, ca. 1450 One can find references to salads- accompanied with a sauce to “dress” them- throughout the culinary history of Italy, France, and even England. A memorable example comes to us from the English gentleman John Evelyn, who in 1699 composed the book “Acetaria: A Discourse on Sallets”, a complete guide to growing, preparing, and eating…. salads. Evelyn was a true salad enthusiast and passionate advocate for the healthfulness and flavor of salads, and prepared detailed notes on which plants were well-suited for cultivation and consumption. He only describes a single sauce for dressing salads, however, which he calls by the ancient Greek word oxoleon meaning “oil and vinegar”. Evelyn’s recipe includes olive oil, vinegar or citrus juice, salt, mustard, horseradish, grains of paradise (a kind of gingery pepper), and beaten eggs. This would serve as a delicious dressing even today. We can therefore think of the oil-and-vinegar mixture as the classical salad sauce, which contains four fundamental elements:

Classical Salad Dressing Formula

Something fatty (olive oil)

Something sour (vinegar)

Something salty (salt)

Something spicy (pepper, mustard, etc). Today, this formula is seen by Italians and French as the fundamental salad dressing: I once had an Italian teacher who would say “Olio, aceto, sale, pepe, e BASTA!” (“oil, vinegar, salt, pepper and DONE!!”) However, from very early times, cooks started finding ways to use other ingredients in salad sauces, either to add complexity or to substitute for the four classic ingredients above. Enter Mayonnaise

In deep history, Mediterranean cooks- probably from Spain or France- noticed that oil could be made creamy by mixing in an emulsifying ingredient: crushed garlic beaten with oil makes aioli, for example. By using various emulsifiers like egg yolk, ground mustard seeds, and even mashed potato, cooks began to emulsify oils into creamy sauces. One example of this is the French remoulade. By the 18th century, the habit of making emulsified sauces grew and mayonnaise- possibly named after the Spanish port city of Mahón- came into culinary fashion. Mayonnaise was made with oil, salt, spices like mustard and a touch of vinegar- the same basic ingredients as a vinaigrette salad dressing- and so it very naturally came to be seen as sort of a creamy version of a salad sauce. Egg yolk- a powerful emulsifier- began to be used often. Mayonnaise was used as a salad dressing for hundreds of years- indeed in the UK “Salad Cream” is a kind of mayonnaise and in the US the mayo-like Miracle Whip is marketed as “salad dressing”. In short, about 200 years ago, Europeans started using mayonnaise as a salad dressing, and using it often. Mayonnaise makes sense as a salad dressing all by itself, since it contains all of the elements of the Classical Salad Dressing formula, just emulsified together. One could also mix other elements with mayonnaise- like extra vinegar or spices- to make more complex salad dressings. The Milk-Eaters There is a great traditional divide in European cuisine between those who rely on milk products for fat and those who rely on olive oil for fat. This is often known as the “butter-olive oil divide”. Since olives thrive in the warmer climes of the Mediterranean countries, these are the “oil eaters”. Since cooler climes favor animal husbandry and make keeping milk easier, these are the “milk eaters”, who use butter, cream, and milk for their fat. It didn’t take long for the classic salad sauce dressing to encounter the oil/milk divide, and soon northern salad makers began to substitute milk or cream for the oil or mayonnaise in their salad dressings. In their 1878 cookbook “Wholesome Food”, Dr. and Mrs. Edmund Saul Dixon of London include a recipe for “Salad Mixture B”, an alternative to oil and vinegar (which was, of course, Salad Mixture A). They said Mixture B- a salad dressing based on cream, vinegar, salt and pepper, was “For those who are prejudiced against the very name of oil, often because they never tasted it; or, possibly, tasted it without knowing what it was.” Dairy-based salad dressings became popular in the northern European countries, especially Germany, Scandinavia, and England, and among immigrants from those countries to the US. In 1898, the “Home Queen Cook Book” contains 34 recipes for salad dressings, 25 of which contain dairy. Creamy dressings- white, emulsified salad sauces- became the norm in the United States, especially in rural areas where dairy was plentiful but oil was rare. The classic creamy salad dressing- sometimes boiled for thickness- followed the following formula, an adaptation of the classical salad dressing formula: Creamy Salad Dressing Formula

Something fatty (cream, milk, or butter)

Something sour (vinegar)

Something salty (salt)

Something spicy (pepper, mustard, onions)

Enter Buttermilk Every milk-eating culture has its fermented milk foods; sour cream, cultured butter, yogurt, etc. In these foods, bacterial action creates sourness, which extend shelf life and add unique tart flavors. Throughout Europe and among Northern European immigrants to the US, people used sour milk products in recipes, and eventually realized a soured milk product could be used to bring tartness to salad sauces instead of vinegar. This meant it was possible to use milk products for either or both the the “something fatty” and the “something sour” in the classic salad dressing recipe, and indeed this is exactly what people started to do. A great example is the German and American “Boiled Dressing” which uses cream, vinegar, salt and pepper, and was seen as an alternative to mayonnaise as a salad sauce. Boiled dressing was extremely popular in the 19th century and was used on a variety of salads both raw and cooked. Sour cream became a popular choice too, since it had the benefit of being both fatty and sour at once. And, finally, buttermilk: this sour-tasting byproduct of butter-making was perfect for salad dressings: it was tart, cheap, and nutritious. Buttermilk dressing became very popular, particularly in small towns in the American West and Midwest, and is represented in dozens of cookbooks from the late 19th and early 20th century. Here is a representative recipe from an Idaho Farm Bulletin in 1927: Buttermilk Dressing for Salads ½ pint thick buttermilk¼ pint mayonnaise dressing

Juice of ½ small onion

½ tsp. lemon juice

¾ tsp. salt

¼ tsp. mustard

⅛ tsp. paprika

⅛ tsp. white pepper

Fold all the ingredients into the unbeaten buttermilk.

You can see that this is just an combination of the Classical and Creamy salad dressing formulas, combining elements of both into a third salad dressing category: Buttermilk Salad Dressing Formula

Something fatty (mayonnaise)

Something sour (buttermilk)

Something salty (salt)

Something spicy (mustard, pepper, onions, herbs)

Since creamy dressings were already very popular, especially in the rural US, buttermilk dressings became popular too; they weren’t all that different from traditional cream dressings, but included soured milk, which was seen as thrifty and healthy. Now, if I were to make the buttermilk dressing above for you today, you would call it “ranch”. It is identical to many modern ranch dressings. But it wasn’t "ranch" yet. “Ranch dressing” had yet to be invented. Here’s how it happened. The “Invention” of Ranch Dressing

The creation story you’ll find about ranch dressing centers around Steve Henson, a Nebraska native who moved to Alaska in 1949 as a plumbing contractor. As the story goes, Steve would cook for his plumbing crews, and they became fond of a salad dressing he made. Henson’s success as a contractor led to an early retirement in California, where he and his wife founded the Hidden Valley Ranch, a guest ranch with a restaurant on the San Marcos pass near Santa Barbara. There, Hudson and his wife hosted legendary parties and dinners, which featured his secret invented-in-Alaska dressing, delicious steaks, and storytelling from Steve Hudson himself. Now, the question is, what was that dressing? Though the “Hidden Valley Ranch” dressing recipe has always been kept secret, former employees have said the original version of the sauce contained buttermilk, mayonnaise, onions, garlic, salt, pepper, and herbs. This recipe is clearly an example of the well-established buttermilk dressing formula above. It’s at this point we should mention that Steve Henson had what at least one of his friends, Allen Barker, called an “artistic truth... in the sense that…Steve told you what you wanted to hear.” In other words, Steve was a storyteller, a raconteur, and an embellisher of tales. The Hidden Valley Ranch wasn’t actually a ranch, it was a motel in the mountains. The bear rug in the motel, which Steve claimed he made after he killed the beast in Alaska, was actually a rug he found at a dump. Alaska seemed to be the location of many of Steve’s tall tales. Therefore, we should take the whole Alaska invention story, like all of Henson’s stories, with a grain of salt. The other Salad Dressing Craze Let’s rewind the clock a few years. In the West, the Palace Hotel in San Francisco had the reputation of being the source for many culinary trends. One of these was the Green Goddess Salad, invented by chef Philip Roemer in 1923 in tribute to the stage play of the same name. The dressing for the salad was based on mayonnaise and vinegar, flavored with the herbs tarragon, parsley, chives, along with garlic and anchovy. The herbs took center stage in this dressing, hence the name. Green Goddess salad dressing grew in popularity throughout the 20th century and by the 1950s it was celebrated by food critics and travelers as “the quintessential California salad dressing”. Premade versions even became available in markets.

Steve Henson had to have known about the Green Goddess trend, and his guests at the Hidden Valley Ranch were certainly primed to become excited about a new, secret-recipe dressing. It seems likely that Steve Hudson took a basic buttermilk dressing, sprinkled some Green Goddess-style herbs in there, and dubbed it his secret “Hidden Valley Ranch” dressing. The Alaska origin story is doubtful. Though it makes sense that Hudson might have made buttermilk dressing while cooking for big groups in Alaska (are Alaskan construction workers big salad-eaters?), he probably wouldn’t have had access to fresh herbs. It seems certain that this story was a California flourish. It was also at about this time that Hudson added another “secret ingredient” to his dressing: MSG. The “flavor enhancer” Ac’cent had become available in the 1940s, and according to insiders the Hidden Valley Ranch used it in their dressing. A dressing legend was born. Steve Henson, knowing a good thing when he saw it, began selling his dressing to neighboring restaurants. One of these, the Cold Spring Tavern, still serves Henson’s ranch dressing, alongside local favorites like barbecued tri-tip and wild game chili.

Soon, Henson began working on a spice-mix version of the dressing, which needed only to be added to buttermilk and mayonnaise to create the signature Hidden Valley Ranch flavor. This was Henson’s true invention- the idea that, instead of selling perishable dressing in a jar, he would package the “secret seasonings” for his “Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing”. These packets contained powdered garlic, powdered onions, salt, pepper, dried parsley, and MSG along with dextrin powder, a kind of starch. He began selling the packets as a dip and dressing mix, and pretty soon he shut down the guest ranch to focus solely on packet production. Henson loved to create a mystique around the brand, featuring a cowboy on the label, playing up the Alaskan origin story, and building a restaurant and supermarket clientele. Hidden Valley Ranch became so successful buyers came calling, and packets of Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing and Dip mix became popular, first in California, and then throughout the United States.

Why did Ranch become so popular?

In the 1960s, as Henson was growing the Hidden Valley Ranch dressing mix company, consumers were primed for a new dressing trend. Freshly tossed salads were becoming more fashionable, as “composed” salads- the molded salads common in the early 20th century- became passé. Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing provided an alternative to vinegar-and-oil, along with a story of Western ranches and California living. “Ranch” was a potent word in the American midcentury- remember “ranch-style homes” were a thing, “Rawhide” and “Bonanza” were the most popular shows on TV, and western style living- epitomized by Sunset Magazine- was definitely “in”. Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing fit in with multiple trends: salads as a part of healthy eating, western-ness, and- perhaps most of all- convenience. Henson’s flavoring packets- which really contained only a few herbs, spices, salt, and MSG, made it seem easy to make a restaurant-quality salad dressing at home. Henson had based his formula on dried and granulated flavorings, which were being perfected in the 1950s. And, using a spice packet along with mayonnaise and buttermilk seemed close enough to “real cooking” to make Americans feel as if they were making something special.

The Ranch Explosion

Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing began getting more and more popular- even beyond the west coast. Remember, in rural America, buttermilk dressings- and creamy soured milk-based salad dressings in general- had already been popular for more than 100 years. In places like Henson’s birthplace of Thayer, Nebraska, creamy, white salad sauces were a kitchen classic. So, in rural America, Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing had a different meaning- it was a continuation of a salad dressing tradition, a commercially available version of a homemade staple, and a tribute to the farms and ranches of middle America. Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing was one of those products that could appeal to consumers on the coasts and to rural areas equally, though for slightly different reasons.

In 1972, seeking to diversify into food products, the Clorox company bought the Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing company. This event signifies Ranch’s transition from a small-but-growing dressing brand to a full-on category. For one thing, during this time, powdered buttermilk was added to the mix, making it even easier to make: now one only needed to add fresh milk and mayonnaise to the contents of the packet. Also, Clorox began marketing premade, shelf-stable bottled dressings in supermarkets. The green flecks of dried parsley- once a big part of Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing’s appeal, began to dwindle in the recipe. These innovations made Hidden Valley Ranch even more popular- and imitators began marketing their own “Ranch” dressings. The Hidden Valley Ranch Dressing brand now was one among dozens of “ranch” dressings, which was becoming an entire category of salad dressings. But, in the great tradition of salad dressings being a sauce anyway, people used ranch for way more than just salads, serving it as a sauce for a great variety of foods. Meanwhile, the inclusion of buttermilk powder in the spice mix made it possible to sprinkle it on anything to give it a “ranch” flavor: from steaks to french fries. The ultimate example of this might be the 1986 introduction of “Cool Ranch” Doritos, which included buttermilk powder, dried garlic, onion, and MSG. Nowadays, any tangy, creamy dressing with onions and garlic will be instantly identified as “ranch”, and any product sprinkled with dried buttermilk and onion and garlic powder will instantly seem “ranch-flavored”. In Conclusion

Today, the ranch dressing phenomenon seems like a weird American quirk. For one thing, it is a goopy, white sauce, laden with fat, salt, and flavorings. Consumers can be seen dipping onion rings and pizza crusts in ranch, and it has become the mandatory sauce served with “hot wings”, a version of deep-fried chicken. Ranch has developed an identity as a tacky indulgence, a proletarian addiction, and the epitome of common bad taste. In truth, however, Ranch dressing is a sauce which has in its history the classical Mediterranean, European cuisine, and the American frontier. It’s a sauce that- under different names- has been with us for hundreds of years. Its re-invention is in many ways the classic American story: Steve Henson took an old recipe and gave it a clear, new, romantic identity. Big food turned it into an inexpensive, abundant, shelf-stable product that could be eaten more or less daily.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How A Coffee Song Changed Music

It was 1959, and coffee company Maxwell House was looking for a new concept for a commercial. The times were changing: satellites were being launched into space, and even mainstream America was becoming interested in modernism and the avant-garde. Maxwell House, perhaps in an attempt to embrace the modern, turned to experimental composer Eric Siday, who was already working in television, and experimenting with new ideas in composition and instrumentation. Siday was interested in the sounds objects made, and saw those sounds as the music of everyday life. He shared this with the French 'Musique Concrete' concept, whose adherents made music from recorded sound samples from ordinary life. He also experimented with so-called 'electro-acoustic' music, using technology to modify and craft sounds into new and different sonic elements. More than anything, Siday seemed enchanted with the idea that ordinary objects could be musical, and could be made to sing. So when Maxwell House called, Siday had an idea: what would a singing coffee pot sound like? The dominant mode of coffee preparation in those days was the percolator, which has a uniquely identifiable action: the thump thump thump of the percolator starts slowly, and increases in tempo until it's a staccato: a steady drumbeat of coffee being made. This concept turned into an experimental musical piece called "Percolabligato", a portmanteau word combining 'percolator', 'laboratory', and the musical term 'obligato'. Siday created the percolator's "voice" by combining the sounds of chinese temple blocks for their percussive plink, a muted gut-stringed guitar for its plunky tonality, and a muted bass for more plunk and tone. Maxwell House must have liked it, because they included it in their next commercial, "The Coffee Pot At Work" which featured "Percolabligato" as a soundtrack. The commercial was a success- the catchy tune seemed to capture the happy, plunky essence of coffee percolating, even though it really sounds nothing like an actual percolator making coffee. This was the essence of Siday's concept of music in the everyday- and it translated into everyone's experience of a countertop coffeepot, somehow. Maxwell House stuck with the concept, and in 1961 they asked legendary television composer and arranger Wade Denning to improve the jingle. He composed an accompanying orchestral melody, allowing Percolabligato to act as a musical figure above a more conventional, soothing piece. The result was "Coffee in the A.M.", which ran as the soundtrack to another Maxwell House ad. This version was more melodic: as a good obligato it used the same instrumentation as Siday's version (temple blocks, gut-stringed guitar and string bass) but by that time Denning had found tunable blocks that could actually play the melody. This version was even more popular than the first version. Denning was asked to make more jingles based on the singing coffee pot, and he came up with many concepts: a western-themed song for a commercial about coffee while camping, a jazz version, and more. The tunes were so in demand they were even compiled into a long-playing record, called "The Maxwell House Coffee Pot at Work". And that's when things got crazy.

In 1962, New Orleans trumpeter Al Hirt recorded "Perky", a cover of the commercial. He included his trademark New Orleans jazz tag at the end, creating an odd mashup of a commercial jingle and a swinging jazz stomper. The single wasn't a hit, but the improbable had happened: a commercial had jumped from television to pop music, and began its life in the world of popular music.

Meanwhile, record producer and executive Lew Bedell heard the Maxwell House theme too, and had a different idea: he approached bandleader and arranger Ernie Freeman with the idea of recording their own "Percolator" song, but instead of using the Percolabligato/Coffee in the A.M., they would write their own similar melody, and therefore retain songwriting credits. Instead of the blocks/guitar/bass combo they used the marimba, played by Julius Wechter, to produce the "percolator sound". The result was "Percolator (Twist)", a similarly perky tune but played in the then-super popular "twist" dance rhythm. They invented the band "Billy Joe and the Checkmates" and used an old high school photo of Bedell on the single sleeve to try and appeal to the teen market. It was a ripoff of a television jingle, played as a rock and roll song by a ersatz band, aimed at the early 60s teen record buyer. But it was great.

And it was a hit. The song went top 10 in early 1962, and became a standard on radio stations across the country. Other bands started to cover the song themselves, including famed surf rock band The Ventures, who included it on their 1963 hit album "The Ventures Play Telstar". From then on, "Percolator" became a staple of surf rock bands everywhere. Meanwhile, the Maxwell House jingle kept going strong. It was the soundtrack to Maxwell House's installation in the 1964 World's Fair, and that same year, the ad was named "Best Musical Commercial" at the Cannes film festival that year. Maxwell House used the melody throughout the 60s and 70s, I even remember it in commercials in the 80s. The most recent commercial using the tune was in 2014, 55 years after its composition. The pop version of "Percolator" had its own life too; Billy Joe and the Checkmates tried to reproduce the success of the tune but no dice. The perky novelty tune persisted, however, and resulted in one more big hit: the 1972 tune "Popcorn" by Hot Butter, a variation on the same theme, this time using a Moog synthesizer to capture the perky, poppy melody. Eric Siday must have loved it, he certainly heard it before his death in 1978. And that's how a little coffee tune somehow, improbably, changed the face of popular music.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering another one of my mothers today.

I'm one of those people who was lucky enough to have many mother figures in my life, as I've written about before. This year, especially, I'm thinking about this woman, my nanna, Eleanor Mary Giuliano. Born Elena Maria Migliore, she grew up in a Sicilian-American family in a small town in Massachusetts, one of 15 families who had immigrated from Southeastern Sicily and settled into an enclave together (a group that included the Giulianos). She therefore grew up surrounded by extended family- which included those who were technically friends but were treated as relatives- which was the way she lived her whole life: surrounded by, comforted by, and caring for people.

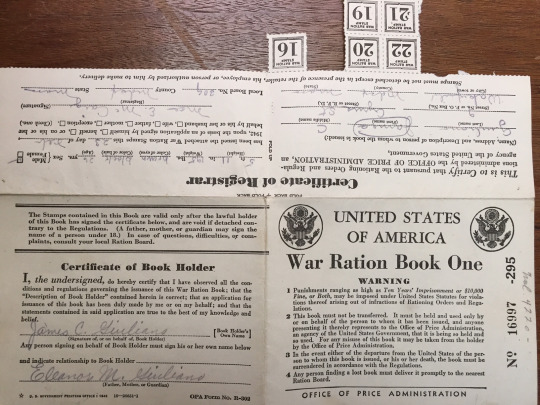

She was 12 when the Great Depression struck, but she was able to persist in her studies, becoming the first woman in her family to graduate high school. She married my nannu (grandfather) and started her own family in the 1940s, during World War 2. Her adolescence and young adulthood were therefore shadowed by economic hardship, scarcity, and anxiety.

This history informed two of her definitive values: an expansive, dedicated concept of family and a strong sense of thrift. She raised four children as a full time mother, but sometimes took jobs and worked often in my nannu's business.

Our family is a close one to begin with, but I got extra lucky: after nannu suffered a heart attack, he and nanna moved into the apartment behind our house. I think I was about 6 or 7 years old, and began to spend my afternoons and weekends in their home. Later, when they moved further away, my parents would send me to spend weekends at their house. So, I got to experience her mothering in a deeper way than most kids get to do with their grandmothers. As I said: extra lucky.

Nanna was known in the larger family for being especially dedicated to our large holiday gatherings, helping muster the legion of aunts and uncles who made the specific foods our celebrations required. But everyday nanna was about thrift. Her weekday meals were frugal: thin tomato broth with pasta and broccoli, or thin tomato broth with pasta and beans, or thin tomato broth with pasta and ground meat. She baked simple, hard biscotti (aka S cookies) to have on hand (always) for treats. I can remember what seemed at the time like an extravagant dessert one night: a single Snickers bar cut in slices and shared among 6 people. I find myself these days cooking her thrifty dishes, wishing I remembered more, but grateful to have gotten a little bit of her seemingly natural, happy frugality.

But of course the best thing is remembering how she looked after us. She made her beds with the sheets tucked so tight you would wake up not having moved an inch. It was like the confining pressure of the sheets was her hugging you all night. She would wake us up with a steaming hot washcloth for our faces, so hot we could not touch it, but which she handled easily in her tough hands. I loved to draw, and she loved to watch me draw, and she would congratulate me and hold my face in her hands, her smiling, eyes filled with love. “Beddu.” she would say. It means “beautiful” but in Sicilian it means more.

Though she has been gone a long time, that love still gets me through hard times; I can go back to it when I need it, like a hidden reserve that never gets exhausted. What an amazing gift that is. And her other lessons- of hard work, and no complaints, and scrimping and saving, and the simple luxury of a hot washcloth- stay with me too. And I'm grateful.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Richard

When we used to go on camping trips as a kid, my dad's friend Bob would sneak into our tent in the morning with a stereo, and blast 'Keep a Knockin' to wake us up. In retrospect, that was the beginning of my love for music that seeks to be thrilling, frenetic, and immediate instead of soothing or lovely. And the absolute master of that form was the one singing that song, Little Richard.

During the 50's music revival of the '70s and '80s, which sanitized rock and roll into an American Graffiti Happy Days jukebox nostalgia, Richard's first hit 'Tutti Frutti' was seen as an innocent nonsense ice cream song instead of what it was- a full-speed, thinly veiled dirty blues played LOUD. It therefore took me a while to get that Little Richard was the connecting force between the old R&B players and the modern soul music I loved: Richard was the bridge between Louis Jordan and James Brown, between Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Jimi Hendrix. And the music I loved most as a teenager- the Specials and Fishbone- borrowed hugely from the stage presence, musical form, and willingness to play LOUD that came from Little Richard. The circle closed for me when Fishbone recorded Leadbelly's "Rock Island Line" with Little Richard himself in 1988. Shortly after that I began playing piano in the New Orleans style, which of course Little Richard was somehow a part of, too. One of my earliest musical highlights was playing 'Long Tall Sally' with an improvised blues band. Again, LOUD.

To play piano in the Little Richard style is to pound the keys as hard as you can, with your fists if need be, but usually with hands wide open, which makes it seem as if you're slapping the piano as much as playing it. You play octaves, since that makes the notes more piercing. He often stood up to play, because you can shout louder when standing. All this reflected the other part of Richard's persona both musical and otherwise- an insistence upon being seen and heard; defiant, proud, and mercurial. This is the truly unforgettable part of Little Richard, and it is a gift to those who- like teenage me- felt a need to be seen. It's that persona that gave courage to the punks and the hip hop artists who made an art form of the insistence of being heard on one's own terms.

Anyway, one should listen to Little Richard's first three albums today, but also all the other artists he influenced. Who are legion. As for myself, I'll just note here that the first song Felix and I played together was "Keep a Knockin'"; since Felix loves the 'crazy drums'. I got him a snare drum and a stool, and I stood at the piano, and we played LOUD.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ul4GJkerx6U

1 note

·

View note

Text

How One Woman Changed the Coffee Industry

Note: last year, I was invited to contribute a piece on the ‘second wave’ of coffee to the Deutsches Museum’s exhibit ‘Cosmos Coffee’. The following is the text of my contribution. Many thanks to exhibit curator Sara Marquart for the invitation.

* * *

In 1968, a professional secretary named Erna Knutsen took a job in a coffee trading firm in San Francisco. Part of her job was to maintain the “position book” in which accounting records were kept concerning the company’s coffee inventory and contracts with BC Ireland, a well-established coffee importer. Although born in Norway, Knutsen had grown up in New York City, a place where––like the rest of America––coffee had become the definitive everyday drink: ubiquitous, commonplace, ordinary. Though coffee’s origins are in Africa and the Middle East, and early European and American coffee drinkers recognized the deep cultural roots and special flavor of coffee, by the mid-twentieth century American enterprise had tamed the exotic coffeehouse and sanitized the smoky, brash coffee roasting companies. Coffee had become slick big business and, by the 1950s, coffee was a quotidian drink for most Americans, a commodity sold pre-ground in cans lining the shelves of polished, sterile “supermarkets.”

By the late 1960s, coffee was in trouble. Per capita coffee consumption had fallen steadily since the end of World War II and young people were rejecting sanitized commercial coffee brands as boring, tasteless, and square. Slowly, in the latter half of the 1960s, a different vision of coffee began to emerge in cities on the West Coast of the United States. Alfred Peet, an immigrant from the Netherlands whose father used to run a coffee roasting company in Europe, had worked in America’s coffee industry and found it lacking in quality and variety. He established Peet’s Coffee, Tea, and Spice in Berkeley in 1966. His shop liberated coffee from its steel cans and sold whole beans, scooped from gleaming brass bins into simple paper bags, alongside exotic teas and spices. Decorated with wood paneling and vintage coffee equipment, Peet’s evoked a nineteenth-century coffee aesthetic and was a rejection of the space-age modernism of the 1960s supermarket.

Soon, Peet was joined by others: in 1968 in San Diego, Bob Sinclair founded Pannikin Coffee Tea and Spice, which sold freshly roasted coffee alongside handmade cookware. That same year, after honeymooning in Sweden and experiencing a coffee epiphany, Herbert Hyman opened his first coffee store in Los Angeles, called the Coffee Bean. In 1971, Jerry Baldwin, Zev Siegl, and Gordon Bowker, three friends who met at the University of San Francisco and who were inspired by Peet’s vision of coffee, founded Starbucks in the city of Seattle, naming the company after a character in Hermann Melville’s classic novel Moby Dick. In 1972, Carl Diedrich, a German immigrant who arrived in the United States via Guatemala, established his own coffee company in Costa Mesa, California. George Howell, also inspired by Peet’s in Berkeley, brought the vision to Boston, founding the Coffee Connection in 1974. Before long, most urban metropolitan areas in the United States had their own small coffee company, dedicated to a common vision of quality coffee and freshness.

From her secretary’s desk, Erna Knutsen could see something unique was happening. These new, young, quality-oriented coffee companies were asking her for “special coffees.” They insisted on the very best quality, seeking out unusual varieties, historic origins, and meticulously prepared “lots.” Realizing that her bosses at the coffee trading firm thought of these new coffee companies as an annoyance, Knutsen began to focus on identifying these special coffees and presenting them to her audience of small, quality-oriented coffee companies, building a little side business. It was in an article she wrote for the Tea and Coffee Trade Journal in 1974 that she called this new market segment “specialty coffee.” In building her business and documenting the rise of a new generation of coffee companies, Knutsen was one of the first to identify what we now call the second wave of coffee––a group of coffee entrepreneurs who, in rejecting the norms of the commodity coffee business of the mid-twentieth century, created an aesthetic and a movement of their own.

Erna Knutsen at her desk.

The specialty coffee era emerged as America rediscovered gastronomy. Led by culinary enthusiasts like Julia Child and Craig Claiborne, a new movement helped Americans discover the regional cuisines of Europe, explore the ethnic diversity of food in the United States, and partake in the excitement of exploring food traditions from around the globe. In 1968, Child’s television show The French Chef was at the peak of its popularity, introducing Americans to the techniques and traditions of French cooking. New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne’s Kitchen Primer was published in 1972, introducing his readers to French, Italian, and Spanish cooking techniques, complete with instructions on brewing fresh coffee. This aesthetic of culinary technique, gastronomic exploration, and a do-it-yourself ethos created a fertile environment for entrepreneurs with a zeal for coffee, flavor, and cuisine. It should be remembered that many of these coffee companies sold spices, cookware, and books alongside coffee. This meant that coffee became central to a lifestyle that embraced good food and drink and the desire to cook “the hard way,” and eschewed the conveniences of frozen-food dinners and pre-ground coffee.

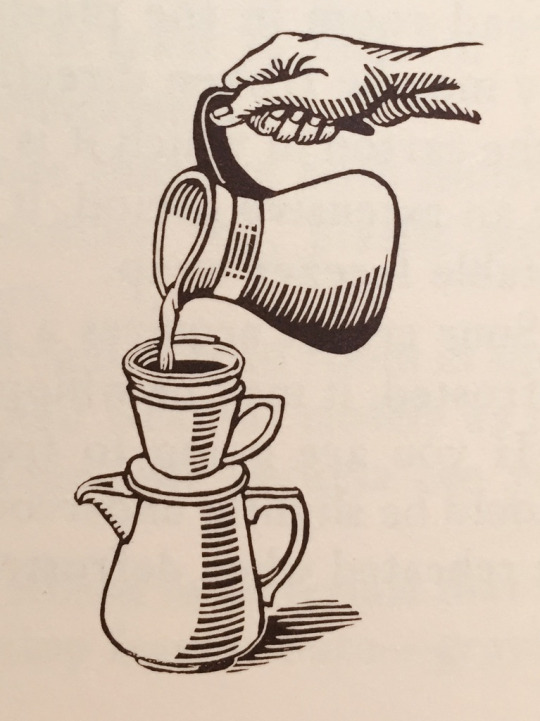

detail of coffee brewing in Craig Claiborne’s “Kitchen Primer” by illustrator Tom Funk, 1972

The second wave of coffee went hand-in-hand with a new sense of cultural exploration. The 1960s and 1970s were an era characterized by ethnic identity and pride, and specialty coffee companies incorporated cultural awareness – particularly of Latin America and the Pacific Rim––into their own identities. Royal Coffee and Knutsen herself sang the praises of Mandheling coffees from Indonesia, George Howell celebrated Huichol art, Pannikin integrated Mexican chocolate and indigenous Mesoamerican folkways into its company identity. All this exemplified these companies’ attempts to communicate and celebrate the cultures from which coffee was sourced. “Offering sheets” and newsletters from coffee importers circulated by post and by fax in the pre-internet era provided a critical education in the coffee trade to the widely-scattered companies of the second wave. Erna Knutsen’s missives, enthusing about the qualities of the coffees she traded, became legendary, as did updates from Royal Coffee and others. Second wave roasting companies from this period embraced the offering sheets aesthetic of the coffee importers and began to expose consumers to the language of the coffee trade, adding regional names like Guatemala Antigua and Ethiopia Harrar to coffee menus, alongside technical trading terms like “Kenya AA” and “Colombia Supremo.”

All of this was done in a spirit of cultural rebellion. Taking their cues from the back-to-the-land and bohemian movements of the late 1960s, second wave coffee companies embraced a style of rebelliousness and nonconformist business practices that came to typify the movement. Bob Stiller founded the Green Mountain coffee company only after the success of his first business, “E-Z Wider,” a company that manufactured rolling papers for use in smoking marijuana and was named after the seminal counterculture film Easy Rider. Paul and Joan Katzeff founded their company Thanksgiving Coffee as a “hippie business.” Although Alfred Peet embraced a conservative personal style, his shop in Berkeley became known as a countercultural hangout, and its regulars became known as “Peetniks,” after the Beatniks.

In the 1980s, these companies began to be embraced by the wider community, having already become well known to the culinary elites and bohemian subcultures of the cities they served. Individual, idiosyncratic outposts turned into local chains of retail stores, which began to host coffeehouses too. In 1982, the Specialty Coffee Association of America was founded. Erna Knutsen helped lead the way in providing a professional association that could assist with establishing standards and educating personnel at the companies participating in the movement.

In the tradition of the second wave’s celebration of European coffee style, Howard Schultz incorporated the Italian espresso bar aesthetic in his Il Giornale project, which became an integral part of Starbucks’ identity. Second wave specialty companies became known more for their beverages than their beans, and the Italian “caffè latte” simply became a “latte”, which in turn became synonymous with specialty coffee in popular culture. The espresso bars and coffeehouses of the specialty coffee companies began to typify the movement, and became essential parts of urban and suburban communities in the 1980s and 1990s. Ray Oldenburg’s 1989 book The Great Good Place specifically focused on specialty coffee shops as important elements in American cultural life, and these second wave companies began to take their role as curators of public space more seriously.

By the 1990s, the second wave of coffee was cresting. Peet’s, Starbucks, Coffee Connection, and many others were expanding rapidly, opening new stores to meet consumers’ demand for high quality coffee beverages, specialty coffee beans, and public spaces where communities could come together. But then the coffee tradition that commenced with a counterculture identity and culinary approach began to be seen as ubiquitous and standardized, and incorporating elements of the 1950s coffee culture it was established to oppose. Coffee shops began to be regular features of suburban strip malls, specialty coffee brands began to appear in pre-ground packages on supermarket shelves, and espresso bars began appearing in gas stations and airports. This led to a great conflict within the specialty coffee movement: was its rapid expansion evidence of “selling out” and abandoning specialty coffee values, or was this a mission with a higher purpose––bringing great coffee to the masses? Were the ideals expressed in Erna Knutsen’s moniker “specialty coffees” possible in the context of mass markets and public stock offerings?

A counter-movement within specialty coffee began to form. This loose group of professional craft coffee roasters established themselves as the Roasters’ Guild, objected to the commercial excesses of the second wave and sought to build a new movement that recommitted to values of quality, freshness, and artisanship. Young entrepreneurs who had worked as baristas or roasters for the second wave companies began to establish companies of their own, seeking to reclaim the mantle of specialty coffee and create new cutting edge coffee.

Some made the transition between generations––Erna Knutsen and George Howell remained relevant to the next generation of coffee entrepreneurs even into their 70s and 80s––while other specialty coffee companies sold or folded. A new generation of specialty coffee had arrived. Trish Rothgeb identified the third wave of coffee in her influential 2003 essay “Norway and Coffee”, published in the Roasters Guild newsletter. Third wavers built upon the culinary drive, cultural exploration, and spirit of rebellion that epitomized the early specialty coffee movement, and brought those values to a new generation. And Erna Knutsen, who had ushered in the original specialty coffee revolution, was there cheering it on.

In June, 2018, Erna Knutsen passed away at the age of 96. Her passing may well mark the definitive end of the second wave of coffee, but the ideals and aspirations of the specialty coffee community live on.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five Spices You Should Never Buy if You Live In Southern California.

I love spices. I am fascinated by the fragrance, the lore, the flavors, the history, and the challenge of cooking well with them. I also love Southern California, our history and our climate. Last, I love the outdoors and plants both wild and domesticated. This post is about the intersection of these three things. Due to our mild, dry, climate, there are a few plants that grow well enough here that they grow along roadsides, or are put in gardens, or are otherwise commonplace. These include certain plants that are also sold on grocery store spice aisles. It always strikes me as odd when I see a Californian buying one of these spices- since they probably walked (or drove, Californians rarely walk) by them on the way to the store. Anyway, for the uninitiated, here are five spices you can find easily in the Southern Californian outdoors. Note: I am using the term ‘spices’ broadly here, including what I think would technically be called ‘herbs’, but we’re not being technical, are we? Tally ho.

1. Pink Peppercorns: In 1830, a sailor from Peru is said to have brought the first ‘Peruvian Pepper’ tree to California. The tree- named Schinus molle after the Quechua word for the plant- is perfect for the Southern California climate: drought tolerant and prolific, the tree creates a lovely shade that evokes the haciendas and missions of Spanish-era California. The tree is unrelated to ‘true’ pepper- the black and white pepper we are all so familiar with- but produces little pink berries which, when dried, are called ‘pink peppercorns’ and sold as such by spice traders. Pink peppercorns have a distinct, but similar piquancy to black pepper, along with a little bit of chile-like heat. The trees- known simply as ‘Pepper Trees’ in California, are everywhere: in parks, planted along streets, and in backyards. The little fruits can be collected and dried, and used as a pepper substitute (they are brittle enough to crush with the back of a spoon- you don’t need a grinder) or a unique, fragrant addition to a masala. Use caution, some people have a reaction to the spice, but to me it’s delicious. If you’d like to visit that original tree from 1830, you still can: it grows in the courtyard of the San Luis Rey Mission in Oceanside, CA. Want to get some for yourself? Try Pepper Tree Park in Tustin, or most housing developments. You won’t have to go far.

2. Fennel Seeds: Foeniculum vulgare is indigenous to the Mediterranean, but was brought to many places in the world, including the Americas. It thrives in the mediterranean-like climate of Southern California, and one can find it growing in vacant lots and on hillsides all over the southland. All parts of this plant can be eaten: I use the feathery spring fronds in soups and salads (it’s a traditional part of the Sicilian fava bean soup maccú) and I’ve eaten fennel pollen at fancy restaurants. But the classic use for fennel is its seed, used frequently in Indian dishes and as the classic, distinctive flavor in Italian sausages. I am famous in my family for my vegetarian Italian sausage, blending mushrooms or soy protein, oregano, salt, pepper, and fennel seeds. Adding fennel seeds to meatloaf, meatballs, or ground pork adds beautiful fragrance and flavor to meat as well. Once you learn to recognize fennel you’ll see it all over the place, I see it most in the kind of hard, clay soil found around railroad tracks and on the bluffs that look over the Pacific ocean. My favorite place to gather fennel is on Camp Pendleton in Oceanside (the bike trail off Las Pulgas has a huuuuuge stand of fennel). As an extra bonus, the ocean breezes give a salty flavor to the fennel seeds. It’s easiest to gather the seeds while they are still green in August, but they can also be gathered when dried and dusky-brown in October.

3. Rosemary: This is an easy one. Rosemary is so friendly to the Southern California environment that landscape designers have a kind of addiction to it, planting huge amounts of it as a ground cover. Bees love rosemary, and its purplish flowers and deep green leaves are lovely to look at. Though I grow it in my backyard, I also know about dozens of rosemary bushes in my neighborhood and in neighboring cities, so it’s never far from one’s grasp. A sprig of fresh rosemary inside a roasting chicken is indispensable, and I love to make potato pizza with just slices of potato, a sprinkle of rosemary, pepper, oil and coarse salt.

4. Bay Leaves: Our Mediterranean climate- besides being accommodating to rosemary and fennel, welcomes other Mediterranean plants such as Laurus nobilis, or Bay Laurel. This is the laurel that the ancient Greeks made crowns from, and which therefore became the root of words like ‘laureate’. It grows easily in California, and has been planted in yards, parks, and roadsides all over our golden state. There is another laurel, native to California, called Umbellularia californica or ‘California Bay Laurel’, and its leaves work for cooking too, although they are stronger. Find or plant a bay laurel tree stat: fresh leaves are so good for cooking soups and stocks. And, once you have an abundant source of fresh bay leaves, you can make THE classic Sicilian backyard dish, Involtini Siciliani, in which slices of beef are rolled around a stuffing of breadcrumbs, pine nuts, and raisins, and grilled on skewers with bay leaves and onion slices.

5. Black Mustard Seed: This one is a little more involved. The glory of the Southern California spring is Brassica nigra, or black mustard. Hillsides explode with the glorious yellow flowers and green foliage of mustard every year, particularly if it’s been a wet winter. This plant was another one brought from Europe, and has gone wild in the warm, dry climate of Southern California. It’s very edible, and its seeds are the very same ones you buy in spice stores. After the yellow flowers are gone, the plant turns brown, and the pods along the main stem are filled with black mustard seeds. These pods can be crushed and winnowed to gather the spice, which is hot and great for Indian dishes.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why If You Care About Tasting Things You Should Know About Rose Marie Pangborn, or, how a Child of Immigrants Founded Sensory Science.

Yesterday, I was having lunch with some friends at a university and, as usual, I had launched into one of my stories. This time, I was telling the story of the New Mexico Chile industry, and how it was founded by a Mexican child-immigrant to the United States, Dr. Fabian Garcia. The woman next to me, a professor of sensory science, said “It’s the same for sensory science.” I had no idea what she was talking about, but she then proceeded to tell me the story of Rose Marie Pangborn.

Born Rose Marie Valdes in Las Cruces, New Mexico in 1932 to Mexican immigrant parents, Pangborn attended and graduated from New Mexico State University, did her Masters at Iowa State, and joined the faculty of UC Davis in 1955. It was there that Pangborn developed her reputation as a pioneering scientist, brilliant innovator, and cherished teacher to a generation of sensory specialists. She wrote three books that were the fundamental texts of modern sensory science: ‘Principles of Sensory Evaluation of Foods’, ‘Food Acceptability and Nutrition’, and ‘Evaluacion Sensorial de los Alimentos: Metodos Analiticos’. In addition to her scientific innovation and writing, she had a legendary reputation as a teacher. She said that she put 5 hours of effort into every 50 minute lecture, and she corresponded with hundreds of her former students, writing them at least one letter per year. Luckily, UC Davis has preserved a few of her lectures on videotape, and some of them are on YouTube. More than anything, though, Pangborn is seen as the founder of modern sensory science. She pioneered ideas about how the senses interact with each other, and how culture and behavior impact our ability to taste. She founded the Association for Chemoreception Sciences and the Sensory Science Scholarship Fund, which supports young sensory researchers to this day. The most respected conference of sensory science, the Pangborn Symposium, is named in her honor. Pangborn died in 1990, but her memory lives on for the scientists and professionals who practice in the field she founded. I have grown to love and respect the field of sensory science, and for that reason and many others, I have a new hero today.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Story of 5282, The Secret Specialty Coffee Code.

Google the number ‘5282’ and the word ‘coffee’ and look at the results: what pops up is a list of seemingly random specialty coffee companies. Is this a secret numerical code? A cryptic, occult message? A strange, numerological coincidence?

There is a reason, and a story behind the reason, and story begins at the dawn of the 17th Century. In 1602, the Dutch government, seeking to compete with the English East Indies Company who had a grip on the lucrative spice trade with the far East, established the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, literally the ‘United East India Company’, known outside Holland as the ‘Dutch East India Company’. Under its charter, the company had the right to, among other things, build forts, maintain armies, and enter into treaties with Asian leaders on behalf of the Dutch government, all in the name of building a powerful spice trading business. The company went to work quickly, building and capturing ships and establishing trading bases in Indonesia, seeking to control the super high-value spice trade.

The Dutch East India Company or ‘VOC’ was ruthlessly successful. A series of battles with the English peaked in 1623 with the ‘Amboina Massacre’, when 20 tradespeople, including 10 English sailors, were captured, tortured and beheaded by the VOC on Maluku, one of the famous ‘spice islands’ I wrote about recently. Anyway, the Dutch basically dominated the spice trade throughout the 1600s. At the end of the century, however, trouble was on the horizon. Increased competition from other trading powers and an unstable market for spices left the VOC looking for alternatives to the spice trade. Coffee seedlings stolen from Yemen in 1699 were planted near the Dutch base on the island of Java and survived; creating a possible alternative to spices as a cash crop for the VOC. In 1711 the first coffee exports from Java landed in Europe, and the Dutch East India Company began its transformation into the biggest coffee production and distribution entity in the world. Alas, the Dutch company was as ruthless at coffee farming as it had been at dominating the spice routes. Using forced labor from local Indonesian farmers under the policy of cultuurstelsel, now known as ‘enforcement planting’, the VOC grew and transported huge amounts of coffee to Europe and elsewhere, and before long, coffee volumes from Java exceeded those from the largest coffee exporter of the time, the port of Al-Mokha in Yemen. By the 19th century, ‘Java’ coffee was ubiquitous, and ‘Mocha-Java’- a blend of coffee from Java and Yemen- was famous. Both terms- Mocha and Java- became synonyms for coffee itself. Java was coffee and coffee was Java. That is, until 1876, when disaster struck: the deadly Coffee Leaf Rust disease hit the island, and the crop was decimated. Though coffee is still grown on the island today, Java coffee never fully recovered.

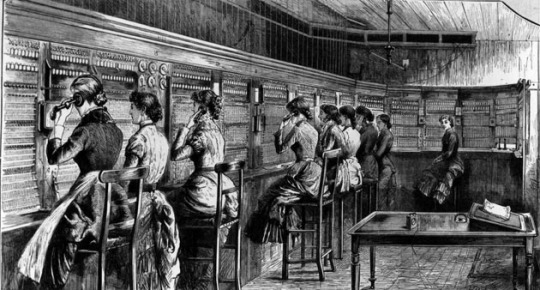

The very next year of 1877, thousands of miles away, Tivadar Puskás, a colorful, brilliant Hungarian who had already had careers as a travel agent and a gold miner, pitched an idea for a ‘telegraph exchange’ to Thomas Edison. The exchange would enable switching between multiple lines, allowing numerous connections to be made among telegraph subscribers in a community. The idea found use, but not in the telegraph: it was perfect for application in Alexander Graham Bell’s new ‘telephone’ system. The first experimental telephone exchange was built in Boston by the Bell company in 1877, and the next year, a commercial exchange was built in nearby Lowell, Massachusetts. These early telephone exchanges were usually named for the town in which they operated; to get connected to a friend, you would tell an operator the name of the exchange where your friend’s phone was connected, then the name of your friend. The operator of your exchange would connect to the other exchange, and the operator of that exchange would connect you to your friend.

Just a year later, in 1879, an epidemic of measles broke out in Lowell. Local doctor Moses Greely Parker, apparently kind of a catastrophic thinker, feared that a bad measles outbreak might wipe out the operators at the popular Lowell telephone exchange, and it would be difficult for replacement operators to be trained on all the names they would need to know to make the connections. He suggested the use of numbers instead of names, and the idea of the ‘telephone number’ was born. In this system, the number of a telephone subscriber- say 252- would always be prefaced by the exchange name. So, ‘Lowell 252’ would become the format for the phone number. For nearly 100 years, phone numbers would follow the ‘exchange-number’ format. Exchange names proliferated beyond place names, as more and more exchanges were built. When making a call, you’d just pick up a phone and tell the operator the exchange and number. (Hence the title of the popular big-band tune ‘Pennsylvania 6-5000’). This is why, when the first dial phones were introduced- like the iconic Western Electric 50AL ‘candlestick’- they had little letters above the numbers: you could dial the first two letters of the exchange- ‘LO’ (aka ‘56’) for LOwell, then the number. Long after the advent of direct dial, people knew their numbers in the exchange-number format: my grandparents’ number in the 1950s was PLeasant 2-2562.

By the 1960s, people stopped using exchange names in phone numbers. Everyone was dialing numbers by this time, and it suddenly seemed easier to skip the ‘exchange’ prefix and just remember the phone number in all-number format. Letters on telephone dials and pads began to seem like a quaint anachronism. (However, no progress goes unchallenged. In 1963 an organization called the Anti Digit Dialing League was formed to combat the pernicious habit of all-digit dialing. They had thousands of members.) In 1967, the toll-free number was introduced, and with it came a new custom: the ‘vanity number’, a custom phone number, requested by the telephone subscriber. Often, vanity numbers tried to spell a word related to a business, using those letters on the dial put there to identify the now-obsolete telephone exchange name. Those old letters had found a new use! ‘Phonewords’ became a craze in the 1980s and 1990s, and many businesses began requesting vanity numbers with built-in phonewords.

The ‘80s and ‘90s were also a boom time for specialty coffee: lots of specialty coffee companies were formed during that time. And, since OBVIOUSLY any brand new specialty coffee company needed to have a cool phoneword-based vanity number, folks were on the lookout for coffee-related four letter words (since phone numbers always end in four digits). The search was on. “Coffee” had too many letters. “Brew” could be beer. What about Java, that old nickname for coffee? ‘JAVA’, aka ‘5282’, was perfect: four letters, a synonym for coffee, kind of exotic, rakish and affable in a jokey-sort-of-serious way. Dozens of specialty coffee companies formed in the 80s and 90s have 5282 in their phone number: Canada’s Colony Coffee and Tea, Olympia’s Batdorf and Bronson, Goleta, California’s Carribean Coffee Company, and my alma mater Counter Culture Coffee in North Carolina are among them. The practice continues to this very day, as companies gleefully request 5282 numbers of their very own. However, the fashion of phonewords has declined somewhat, and companies don’t as often write their number as 1-800-555-JAVA now, preferring the slightly more dignified 1-800-555-5282, and people eventually forget the number-word connection. Do they know that the number has in its history the 17th century spice trade, the rapacious Dutch East India Company, stolen coffee seedlings, enforcement planting, a Hungarian inventor, a measles outbreak, and a paranoid-yet-clever doctor from New England? Does anyone remember that ‘Java’ is an island, and that people used to actually talk to an operator when they needed to make a phone call? Regardless, here is what I will promise you: if you care about coffee, you’ll be seeing the numbers ‘5282’ EVERYWHERE now.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Know your cultivars: New Mexico Chiles (New Mexico No. 9, Big Jim, and R Naky), but more importantly the heroes Fabian Garcia and Roy Nakayama

As summer fades in the Southwest, boxes of green chiles begin to appear in supermarkets. Usually emblazoned with the name “Hatch Chiles”, some places will sell you the chiles and roast them for you in the parking lot, the air filling with the amazing smell of roasting chiles, making the skin brittle and peelable. You might think that Hatch is the chile cultivar name, but it’s not. Hatch is a small village in Southern New Mexico, and is the more or less official capital of chile cultivation in that state. Hatch chiles are New Mexico chiles, and New Mexico is the heartland of the chile in the United States.

It was of course the indigenous people of the Americas who discovered and embraced the chile, building entire cuisines around chile’s unique, delicious flavor. At the end of the 19th century, the Hispanic residents of New Mexico grew chiles in backyard gardens, for home drying and use as a spice. That was before Fabian Garcia. Born in the Mexican state of Chihuahua and orphaned as a young child, Garcia immigrated to New Mexico with his grandmother where she found work as a housekeeper. He began attending school, and working in the orchards owned by the family for whom his grandmother worked, learning lessons about agriculture, pests, horticulture, and farm work. When the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts opened, Garcia was first in line to enroll, and was in its very first graduating class. After some graduate work at Cornell, he returned to New Mexico A&M to pursue his masters degree, eventually joining the faculty of that college (which is now New Mexico State University). Garcia was the only person of Mexican heritage on the faculty, and became the first Hispanic person to run a land-grant agricultural research station in the United States.

Fabian Garcia had a vision for his agricultural work: if he could breed a unique variety of chile pepper, consistent in flavor, well suited for the microclimate around Las Cruces, suitable for roasting and eating as a vegetable, that chile might be a good and profitable crop for New Mexico. In 1913 he set to breeding, collecting chiles grown around Southern New Mexico, aiming to create a chile that was not too hot- he wanted the chile to be accessible to Americans not yet accustomed to eating chile peppers- but flavorful, productive, and attractive. Through careful breeding, he developed the New Mexico No. 9 variety, which created a whole new category of chile pepper, now known as the ‘New Mexico Type’. This chile was a cultural milestone- it made commercial chile production in New Mexico possible, including canned green chiles. This paved the way for Mexican-American food to flourish all across the United States: chiles rellenos, green chile salsa, enchiladas, pork in chile verde, and bottled hot sauce. Garcia is therefore both the founder of chile agriculture in New Mexico and is responsible for the proliferation of Mexican-American food. Today, New Mexico is the biggest producer of chiles in the United States, due entirely to Fabian Garcia’s vision and hard work. Garcia remained a professor at New Mexico A&M until he became bedridden with Parkinson’s Disease; he refused to retire voluntarily, always hoping to return to work. Although he had naturalized as an American citizen at 18 years old, he was fiercely proud of his Mexican identity, and he bequeathed a gift to his beloved university to build a dormitory and establish scholarships for Hispanic students. The horticultural farm at the university still bears his name. In 1923 in Las Cruces, a boy was born to Kaichiri (John) Nakayama and his wife Tome, immigrants from Japan who had settled in New Mexico to farm. The boy, named Roy, was one of eight children. The Nakayamas rented the farm they worked, and when they finally had enough money to purchase land of their own, they had to put it in their child’s name because of the New Mexico alien land law (1918) and the Oriental Exclusion Act (1924). Roy Nakayama worked on the farm and as he intended to be a farmer, he enrolled in New Mexico A&M, pursuing courses in horticulture and plant pathology. In 1943, after two years of college, Nakayama enlisted in the Army to fight in World War two. He fought in the Battle of the Bulge, and was captured by the Germans, spending eight months in a prison camp. When he was released, he weighed only 87 pounds. Nakayama returned to New Mexico A&M to resume his studies, but he was refused re-admission because of his Japanese ethnicity. The faculty objected to his exclusion, and ultimately Roy was able to attend. He was a successful student, ultimately receiving his PhD in plant pathology, and he joined the faculty of New Mexico A&M, teaching classes in horticulture. He began breeding chile varieties, and in 1975 introduced the ‘Big Jim’ chile. Bred to be big, Big Jim is now the most famous of the New Mexico varieties, and its flavor is said to be more complex than any other. Many of the “Hatch” chiles you see at the market will be Big Jims. Over the years, Nakayama became known as ‘Mr. Chile’ for his dedication and focus to breeding chiles and promoting chile agriculture in New Mexico. One of the last varieties he bred is called ‘R Naky’, after his wife, Rose Nakayama. It is a chile bred to be exceptionally sweet (isn’t that nice).

The chiles of New Mexico are amazing and delicious, and are a treasure of American cuisine. They are also an economic mainstay of the state of New Mexico, bringing both agricultural income and tourist income (the Hatch chile festival is a big deal nowadays). I have myself been roasting New Mexico chiles on my backyard grill, listening to them pop and sizzle as the skins char, dumping them into a paper bag to cool and soften, and peeling and seeding them at my backyard picnic table. I’m fairly sure I have Big Jims this year, and they have a bracing citrusy flavor, and a powerful heat. They are gorgeous. Epilogue: As I write this, DACA, a program intended to protect from deportation those undocumented immigrants who immigrated as children to the United States, has been suspended. It is deeply ironic to me to learn the story of New Mexico chiles- an industry that was founded by Garcia, a child immigrant, and modernized by Nakayama, child of immigrants. These people established a multimillion dollar industry for the state of New Mexico, which creates jobs, livelihoods, and culinary joy all over the southwest. It’s just one example of how immigrants like these- and like the dreamers- make us richer both culturally and literally.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Read ‘New York City Coffee: A Caffeinated History.’

Actually, I did not read it so much as I devoured it. As soon as it arrived on my doorstep, I excused myself from my family and repaired to a chair outside, and the night came and I didn’t want to move. New York City Coffee is that kind of book: it brings together a real history, a fascinating cast of characters, approximately a million anecdotes, a little smart commentary and a hefty portion of wit, all delivered as if from a friend. I love a book that is this smart and still treats the reader like a friend. The author, Erin Meister, is in fact a friend, but that’s beside the point. In four chapters and just over 100 pages, Meister has spun together an idiosyncratic, deeply loving look at the coffee history of New York. We need more coffee histories, you know: almost everything we think is new has actually happened before; women and men before us have faced the same challenges we face, and have weathered the vicissitudes of coffee over decades and generations. We in coffee have this tendency to feel as if we are inventing the trade all the time, and this has the effect of leaving us feeling rootless. In this little tome Meister explores the coffee roots of a single city, tracing them right up to the coffee bars of the current day. She introduces us to indelible characters like Alice Foote MacDougall and Clem Paddleford, who laid many of the foundations on which we build our coffee ideas. Meister’s tales teach us tons about the history and meaning of the coffee commodity exchange, the roasting machines we use, and the quirky terminology of our trade. I am so grateful for this book; it’s a real contribution to the canon of coffee history and it’s earned a permanent place on my coffee reference bookshelf. Thanks, Meister.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Labor and Coffee

It’s International Workers’ Day today, which means it’s a good time to reflect on the labor that is contributed by people all over the world to support our lives, our economies, and our aspirations. And so it is for us in coffee- today is a day for honoring workers in coffee. Because coffee is so international and complex, it’s a bit complicated to identify all the laborers in the miraculous chain of coffee. I’m going to touch on a few of these, as a part of my own reflection on labor today.

The small farmer- Many of those who work in coffee are people who own a small parcel of land, and produce coffee from it as their main livelihood. These people- or, rather, families, as coffee growing of this kind is really a family occupation- are often responsible for a huge and diverse amount of labor that goes into coffee agriculture: grading the land, planting coffee, fertilizing the soil, dealing with disease, pruning, picking coffee cherries, depulping, fermenting, drying, and all the various transportation between these stages. The family that runs a small farm has to be all things- which is a big challenge, especially in the height of coffee season. I’ve known small farmers who rise before dawn to begin picking, who gather fruit all day in baskets, and who begin the task of running the hand-cranked depulper and fermenting the coffee at sunset, a task which can run into the early hours of morning. A few hours later, they rise again and start all over. Health care and social support are often difficult for the small farmer to access, and of course the life of every small farmer is at the mercy of weather, crop disease, and pests. A small harvest can mean hunger later in the year.

The farmworker- on larger farms, labor comes from farmworkers, who engage in the various tasks of running the farm as employees. These workers have to shift between jobs- one day carrying compost on their backs to remote parcels of the coffee farm, the next day pulling up old trees and replacing them with seedlings, the next day pruning and clearing weeds. During harvest season the main activity is picking, and pickers (sometimes permanent workers, often temporary workers) spend their days in the tricky pursuit of perfectly ripe cherries, inconveniently nestled right against unripe and overripe ones. Pickers are usually paid by volume rather than by the day or hour, which means that speed is of the essence, difficult to achieve on steep and remote coffee farms. Practices vary around the world, but always picking becomes more difficult as workers age and hands become less nimble. A great resource on this topic from the SCA is here.

The wet-mill worker- coffee-processing mills exist all over the world, and their purpose is to remove the layers of coffee skin and fruit from the bean before drying. Cherries are loaded with water, and are therefore heavy- wet-mill working requires hours of shoveling cherries, skins, decomposing waste, and drying seeds. In Africa, the last of the fermenting mucilage is often removed by agitation using a paddle or even the feet, in Latin America wet-mill workers often push fermented coffee through channels to clean it. Equipment must be cleaned and repaired constantly, the water and the decomposing mucilage are corrosive to the equipment and the smallest bit of day-old rotting mucilage can show up on the cupping table, precipitating the worst possible outcome- the rejection of a promised lot of coffee.

The dry-mill worker- Coffee is brought to other mills to dry and be husked before shipment, and patio-drying and table-drying are often labor-intensive activities requiring raking, turning, and sorting under the hot sun. Once dry, the coffee is husked in mills that are packed with heavy equipment, which can be dangerous and loud. Finished coffee is loaded into heavy bags (always over 100 pounds), which are carried on the backs of people- stacked in warehouses or loaded into containers for shipping. I have watched as people load heavy sacks on their backs, run at full speed up a narrow plank into a container, drop the sack, and return at full speed to gather up another sack. This is literally backbreaking work, and takes a heavy toll on the body. In other parts of the dry mill, sorters- often women- comb through finished coffee on a table, floor, or conveyor belt to pick out discolored, broken, or damaged beans. Hour upon hour is spent picking, sorting, and removing those distasteful ‘defects’.

The transport worker- Coffee’s story is about distance. Coffee is grown at a farm that is distant from a port, which is distant from another port, which is usually distant from a roaster, which is usually distant from the coffee shop or consumer. Coffee travels between these places on trucks and boats and pallets and lifts, which are run by transport workers: truckers, ships crews, port workers and warehouse workers. Containers which are loaded on people’s backs are often unloaded on people’s backs too, and this can happen 3 or 4 times in a coffee’s journey. Moving a sack of coffee is dead weight- which can wear on arms and backs and legs.

The roaster- Roasting is skilled, solitary work. Loading sacks of coffee into roaring, moving, turning, 400 degree ovens is daunting, but the real challenge of roasting (at least to me) is the solitude- roaster noise and hearing protection create a cocoon for the roaster, and they might never speak a word to another person for an entire shift. They are responsible for the revelation of coffee- using their skills and senses to transform a coffee into that which we recognize as ready to be brewed- but this entails risk: a burned batch is ruined, and an under-roasted one is a waste of potential. Roasters are constantly anxious about the risk of fire, and are managing hoppers and roasters and cooling trays and bins and warehouses, which is challenging work indeed. A small mistake can mean a loss of thousands of dollars for the business, and roasters are held to high standards of accuracy and efficiency.

The packer- coffee is put into bags and bins and cans and boxes by people, who often use scoops and scales and other equipment to achieve their task. This process is sometimes automated- but mostly it’s hand work: labeling and filling and sealing and loading and labeling and filling again, rushing to meet shipping deadlines and production schedules. This can be hard on hands and eyes and backs, as anyone who has ever worked in a warehouse can attest.

The barista- the final step is when coffee is presented to the consumer, either as a beverage or as an ingredient to be taken home. Either way, the barista is there to protect and prepare the coffee, using the skills of brewing or espresso making or milk preparation or beverage assembly. This can take a physical toll on the worker- standing for long periods of time behind a counter, or using one’s wrists and hands to prepare coffee and keep things clean. But there is another whole category of barista labor- the emotional labor that goes into practicing compassion for the consumer (who, after all, generally hasn’t had their coffee yet) and creating an atmosphere of comfort and happiness for the guest. Sadly, as service workers, baristas are sometimes subjected to harassment and conflict, and have to deal with it all with equanimity and grace.

The above is only a small sample of the laborers in coffee: I have neglected many occupations and workers who are necessary in making coffee possible. The point is only that every single cup of coffee represents hour upon hour of physical, mental, and emotional labor by many people in many places and of many kinds. It’s almost impossible to conceive of, and even harder to express our respect for and our solidarity with these workers. But today is the day that we try. Happy international workers’ day everyone.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanksgiving, Lorenzo, and Why Trump is Wrong.