home of the unfurling decarabia

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

It's the Karukozaka Class Reunion of 2025, and you're invited to take a look at the alumni demons who graduated and went on to (hopefully) better things! Who changed the most since they left? Who stayed the same? Who remembers when Goblin had that embarrassing pixel change in 2nd year? We all pretended not to notice but he was SO self-conscious about it- oh shit he's coming act natural.

Hey Goblin, long time no see! How's the family? The 2nd of a three part series about if...'s designs and sprites. This one has the most obsessive details yet of any video I've made so far!

youtube

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Defines A Demon || Megami Tensei 101

A brief explanation of the context behind the term "demon" in Megami Tensei and what they represent thematically. I'm trying for a new style of video that's concise and accessible, but still has a lot of depth.

youtube

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

What if... you were too cool for demon school, and the gnarc teachers had to hold you back a grade... permanently? Discover 20 or so demons who were in SMT if... and still are, because they never graduated onto other games! Witness all eight forms of terrifying Chefei! Get excited for the next part that I haven't started yet! It's all here!

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

"Beastman: I usually take whatever I can get, but a name has eluded me...

Wait!!

I should get it from you!

The names of my saviors—it’ll work wonders!

Your names are... What?... Hazama... and Amon... Combine them... Hazamon... No,... Mammon... Yes! Mammon! From now on, I'm Mammon!"

atlus rerelease quality writing (which i guess is a compliment for a mobile phone game)

Just in case you were interested in this piece of information, over at the SMT Wiki (I know, I know, you hate that website but please spare any groaning til the end of this message), on the page for Shin Megami Tensei: if... Hazama's Chapter, there is a link that goes to a Pastebin entry that has a fantranslation of its script. The maker does admit that the correctness of the translation is debatable, but he is open to corrections from others.

I don't hate the Fandom MT wiki (the independent wiki has much better potential), though I indeed don't care much for Fandom itself. Especially now that they both own Giant Bomb and are pressuring it to change its content. No Giant Bomb and this blog probably wouldn't exist. At the very least, I wouldn't have met Soren.

Here's a link to the Pastebin:

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

SMT mermaid is alright coz I don't think there's much to express on (typical) mermaid's lore aside from being associated with sea disasters, fantastic "doomed" romance, vanity and lust

but I wish they had more organic look because the "gloves" and thigh high tails looked more like prosthetic instead of like a part of their body (mostly probably because doi wanna see some ass)

had some idea that they'll bit more like a sea "angel" (as a concept, not the real animal). They inhabit the hadal zone dragging souls to the depth of the davy jones locker. You could probably imagine a seapunk smt nocturne where when demi merman dies, he gets an entire circle of these sea angel mermaids

they're modeled after hadal snailfish, which seems to ditch scales for translucent body

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History of the Kuzunoha Clan

Hey, I'm not dead. I've just finished a new video all about the Kuzunoha Clan. It focuses on the real-life mystical concepts that inspired them, explores their in-universe history, and explains how they function as a group using info from the games, manga, novels, etc. If you're at all interested in learning about Raidou Kuzunoha's background in preparation for the upcoming remaster, this will cover basically everything we know about the clan.

This video is not very spoiler-heavy, except arguably for the 2nd section covering material from the original Devil Summoner; however, this video does cover the entire Devil Summoner series if that is an issue for you.

youtube

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raidou 1 is being remastered so now's a great time to get stuck into my Raidou 1 video and learn all the DEEP LORE behind the demons in the game!!!! Do it or else!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

youtube

Newest video finally done, featuring artwork from t2_hatori!

EDIT: I forgot the bit where I talk about Nagasunehiko and delve into Abe Shinzo conspiracies. Reuploaded.

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't think I've ever seen you comment on misemono before - any thoughts on them? I finished The Carnival of Edo: Misemono Spectacles From Contemporary Accounts to gain some context after seeing them mentioned in the Lafcadio Hearn account of the Kudan, so they've been on my mind. I like the mock-duelists that shill resurrection elixir to their crowd and the guy who painted a Buddha statue onto the telescope.

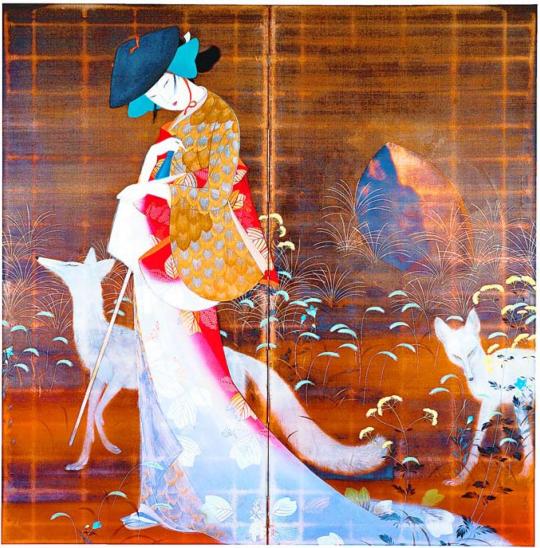

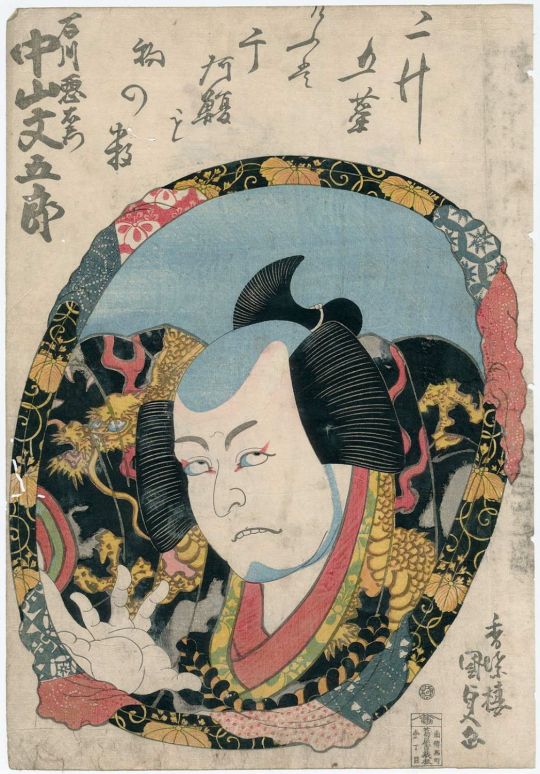

I completely missed this question, I’m sorry - it must’ve spent like half a year in the depths of my ask box. Apologies! Anyway, It’s kind of funny how rarely they seem to come up in historical fiction about the Edo period despite being one of the most widespread forms of entertainment in it, isn’t it? I think my favorite category of misemono displays are the tennen kibutsu ones, ie. unusual animals (see Daniel J. Wyatt, Creatures of Myth and Modernity: Meiji-Era Representations of Shōjō (Orangutans) as Exotic Animals, p. 73 for an overview of classification). Special shoutouts to the anti-smallpox cassowary (Creatures…, p. 74) and to the “thousand-year-old-mole” (千年���龍) which was reportedly actually a badger hyped up as a long-lived “king of moles” on the account of vague anatomical similarities (Creatures…, p. 73, footnote 2). It’s kind of funny that the often folklore-based, or entirely made up, advertising for misemono displays could lead to people being disappointed - a frustrated visitor to a show held in Tokyo in 1875 penned a strongly worded letter to Yomiuri Shimbun in which he describes his confusion after seeing an alleged shōjō (ie. an orangutan, though in this case apparently a monkey was displayed as a specimen of the earlier shōjō from the realm of literary fiction), as the animal “didn’t speak as it has been written that it should in the Book of Rites, and it didn’t drink sake as Noh songs say it does” (Creatures…, p. 79). As far as Markus’ article you’ve mentioned goes, the Buddha telescope is definitely my favorite; I must say “a prodigy was a prodigy, irrespective of its commercial exploitation” is a great quote too. A final interesting misemono-adjacent curiosity is that in the 1770s Momiji, the demonic antagonist of the well known legend about Taira no Koremochi, starred in an illustrated book (kibyōshi) entitled Oni no Shikogusa (an annotated English translation, The Demon Girls Comes to Edo, courtesy of Adam Kabat, has been recently published in the collection The River Imp and the Stinky Jewel and Other Tales. Monster Comics from Edo Japan; p. 309-370) in which after many trials and tribulations (including becoming an agent of king Enma) she ends up as a misemono attraction herself. This was apparently a nod to a veritable “superstar” of a contemporary show simply remembered as “the oni girl” (oni musume); many other misemono sensations, like a depiction of the Amida Triad made out of dried fish, are referenced too. As a way to gain insight into the Edo period mentality, both when it comes to misemono and to the often playful and irreverent attitude to earlier literature, it’s a great read all around, I might cover it in more detail some day.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

WLW - Women-Loving Wizard(esse)s? Lesbian love spells from Roman Egypt

I said there will be no dedicated femslash february-adjacent post this year, and in the end that turned out to be nominally true. That’s only because this article, which I didn’t plan too far ahead, is a few weeks late due to unforeseen irl compilations. In my previous, also unplanned, article I’ve included a brief introduction to the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri, and discussed some unusual attestations of Hecate in them - perhaps some of the most fun material to research not directly related to anything I usually write about I’ve had the pleasure to go through in a long while. This text corpus is a gift that keeps on giving in general, but perhaps the single most welcome surprise was learning that there are at least two - possibly three - examples of lesbian love spells in it. While I considered waiting for pride month to cover them, I ultimately decided to publish an article about them much sooner (I have a different, highly esoteric pride month special in the pipeline already though, worry not).

Without further ado, let’s take a look at these unique wlw (women-loving wizard) testimonies and their historical context. Which supernatural entities were, at least for these women, apparent lesbian allies? Why does one of the lesbian spells contain an elaborate poetic passage pairing Osiris with Persephone? Why Lucian of Samosata might be the key to determining if 2 or 3 lesbian love spells are available to researchers? Answers to all of these questions - and more - await under the cut!

Before you proceed, I feel obliged to warn you that the article discusses historical homophobia, so if that might bother you, you’ll have to skip one of the sections. Furthermore, some of the images, as well as parts of the text itself, are not safe for work.

Part 1: the spells

Through the article I will refer to the discussed texts as “lesbian spells”. This is merely intended as a convenient label, not a definite statement - we can’t be 100% sure of the orientation of everyone involved, obviously. On top of that, none of the spells give us any hints about the terms the women involved in their composition used to describe themselves. Needless to say, the fact that the discussed spells even exist is nothing short of a miracle. The corpus of magical papyri and other related objects like inscribed tablets and gems is relatively small, and covers a short period of time - for the most part just the first four centuries CE. On top of that not all of them are specifically love spells. For comparison, while there is a sizable corpus of Mesopotamian love incantations spanning over two millennia, not even a single lesbian one has been identified among them so far (Frans A. M. Wiggermann, Sexuality A. In Mesopotamia in RlA vol. 12, p. 414).

They also represent one of the only indisputable examples of ancient texts in whose composition women who at the very least desired relationships with other women were involved (Bernardette J. Brooten, Love Between Women. Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism, p. 105). How active that involvement was might be difficult to ascertain, though.

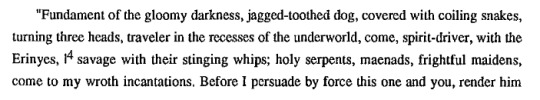

Spell 1: angel or corpse daimon? The first spell of the discussed variety I’ve stumbled upon lacks a distinct title, but it’s included in the basic modern edition of many of the magical papyri, The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells edited by Hand Dieter Betz, as PGM XXXII. 1-19 ( p. 266):

It was discovered in Hawara, an archeological site in the Fayum Oasis, and most likely dates to the second century CE (Love Between…, p. 77). At the time of its initial publication, some doubts were expressed about whether it’s really a love spell by authors such as Richard Wünsch - as you can imagine, for at least implicitly homophobic reasons - but it’s been the consensus view for a long while that it's explicitly lesbian. I left the brief comment included in the standard modern edition on the screencap above to highlight this. It needs to be stressed here that the opposition to this now mainstream interpretation was a minority opinion in the first decades of the 20th century already, and was conclusively rejected as early as in the 1930s (Arthur S. Hunt notably contributed to this) and basically never entertained by any authors since (Love Between…, p. 80-81). Sadly, there is not much to say about the dramatis personae of the spell. Herais’ name is Greek, but her mother’s, Thermoutharin, is Egyptian; both Helen and Sarapias are Greek names, but the latter is theophoric and invokes, as you can probably guess, Serapis. This sort of combination is fairly standard for Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, and it’s not possible to determine if one or both of the women involved were Greeks who settled in Egypt, Egyptians who adopted Greek names, or if they came from mixed families (Love Between…, p. 79).

While it’s likely Herais simply commissioned the spell from a specialist (Love Between…, p. 109), it’s worth noting that in the most recent commentary on it I was able to find, Heta Björklund argues that she was a magician herself (Invocations and Offerings as Structural Elements in the Love Spells in Papyri Graecae Magicae, p. 38). She also assumes some of the heterosexual love spells were the work of female magicians. Sadly, in the relatively short period of time I dedicated to preparations for this article I failed to find any study which would make it possible to establish whether this is a proposal with more widespread support. Female conjurers are certainly not uncommon in works of fiction, though, so even if the magical papyri were mostly written by men until proven otherwise I see no strong reason to doubt that we’re really dealing with a wlw (women-loving wizard).

The vocabulary employed in Herais’ spell is identical as in the heterosexual love spells. However, since examples aimed at both men and women are known, and do not significantly differ in that regard, the fact most of them were written by men seeking to secure the love of women doesn’t necessarily imply Herais necessarily took a masculine role herself just because she adhered to the same convention regarding magical formulas (Love Between…, p. 105).

An interesting aspect of the spell are its theological implications. At least from Herais’ perspective, Anubis, Hermes and “the rest down below” - in other words, a host of other unspecified deities residing in the underworld, not to mention the entity invoked to help her - not only would have no objections to her orientation, but would actively aid her in securing the love of the target of her affection (Love Between…, p. 80).

Invoking deities is basically a standard in love spells, regardless of the orientation of the people involved. Three distinct categories of them can be identified: Aphrodite and her entourage (ex. Eros and Peitho); heavenly deities (like Helios and Selene) and, perhaps unexpectedly, underworld deities (Hecate, Hermes, Persephone and others) - and, by extension, ghosts. From the first century CE onward it was actually the last group which appears most commonly in love spells. This likely reflects their association with magic and fate (Invocations and Offerings…, p. 45-46).

While there’s no point in dwelling upon the references to Anubis and Hermes, which are self-explanatory, there is some disagreement about the nature of Evangelos, who Herais basically asks to act as a supernatural wingman for her. Björklund argues that he should be interpreted as an angel or divine messenger (Invocations and Offerings…, p. 38). This is not implausible at first glance. Angels are invoked in multiple other spells from the magical papyri as helpers. For example, PGM VII 862-918 focuses on a request to Selene to send one of her angels presiding over a specific hour of the night (Leda Jean Ciraolo, Supernatural Assistants in the Greek Magical Papyri, p. 283; as a side note, there's a chance I will discuss early angels - especially the oddities like PGM angels - in a separate future article).

However, another view is that Evangelos was a “corpse daimon” (nekudaimon) - this would offer a good parallel with other love spells. What was a corpse daimon, though? Simply put, the restless, but not necessarily malevolent, spirit of a person who died prematurely (Love Between…, p. 80). In Egypt this idea intersected with other views on the origin of ghosts - for example that they could be people who died so long ago nobody made tomb offerings to them (Ljuba Merlina Bortolani, Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt. A Study of Greek and Egyptians Traditions of Divinity, p. 224). It’s possible that in some cases, perhaps including Herais’, papyri with spells have been deposited in, or at least read above, the graves of people who died in circumstances which made them eligible to become corpse daimons, in order to secure their help (Love Between…, p. 80). There is also evidence that food could be left for them in appropriate places instead, as attested for example in the “love spell of attraction in the presence of heroes or gladiators or those who died violently” (ωγὴ ἐπὶ ἡρώων ἢ μονομάχων ἢ βιαίων; PGM IV 1390-1495). This was a practice derived from a common type of offering to Hecate and her ghost entourage (Magical Hymns…, p. 223). It’s worth noting a daimon didn’t necessarily have to be human - the “cat spell for all purposes" (ἡ πρᾶξις τοῦ αἰλούρου περὶ πάσης πράξεως; PGM III 1-164), described as equally effective whether employed as a love spell, enmity spell or… a way to alter the results of chariot races (a relatively common goal in the magical papyri). instructs how to enlist the help of a “cat daimon” (τὸν δαίμονα τοῦ αἰλούρου). In this case the magician has to first “create” this entity by offering a cat as sacrifice, though, instead of invoking a preexisting daimon (Invocations and Offerings…, p. 32).

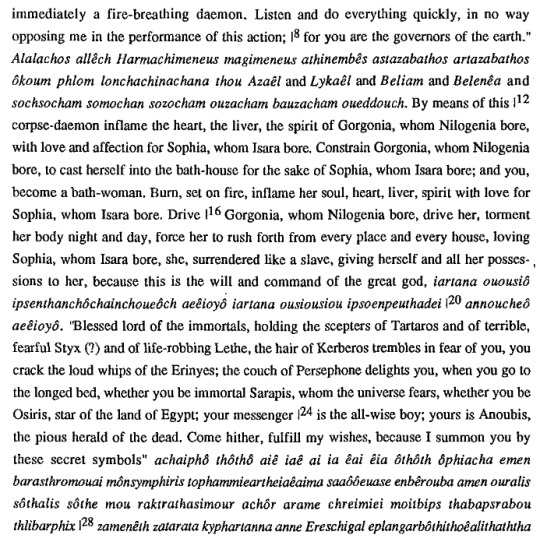

Spell 2: Osiris, Persephone and inflamed liver

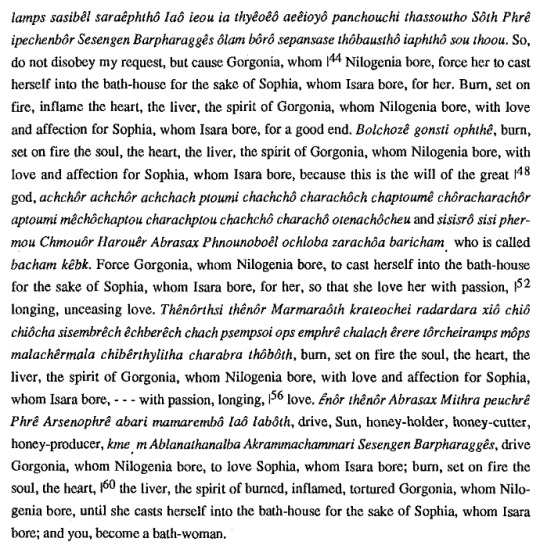

While the spell discussed above seems to be brought up online the most often in discussions of references to lesbian and gay love in antiquity, the second known example is much more elaborate. Its standard translation was published in 1990 in the first volume of Robert W. Daniel’s and Franco Maltomini’s Supplementum Magicum, intended as a supplement to the already mentioned compendium of translated magical papyri (p. 137-139):

The text is inscribed on a tablet discovered in Hermopolis, and dates to the third or fourth century CE (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 132). It’s possible it was commissioned from a magician, rather than written by Sophia herself. Both her name and Gorgonia’s are not declined, which might indicate that a magician simply inserted them into blank spaces in a preexisting formulary offered to clients (Love Between…, p. 88-89). It’s nonetheless quite interesting as a work of literature, even if it was just a stock formulary sold over and over again. Some sections deliberately use poetic forms. Furthermore, some of the long compound words in them are entirely without parallel. It’s possible that this was a conscious source meant to create a peculiar overwhelming atmosphere, suitable for invoking ghosts and underworld deities (Love Between…, p. 88). While Herais’ spell is brief and vague and doesn’t really reveal much about her desires, beyond establishing that the object of her affection was a woman and that she believed supernatural entities would plausibly approve of pursuing her, Sophia’s commissioned(?) one seems to involve a pretty detailed fantasy. Of course, an argument can be made that it doesn’t necessarily specifically reflect her individual desires, but rather the widespread perception of bath houses as places suitable for flirtation and related ventures (Love Between…, p. 89). Still, while obviously we’ll never be able to know, it’s interesting to wonder if she perhaps had to choose from a larger repertoire of love spells offered by a magician (or perhaps even by multiple magicians) and went with the formula which matched her expectations to the greatest degree. Interestingly, the idea of a love spell being more effective in bath houses recurs in multiple magical papyri. The view that they can be haunted was fairly widespread, which made them a favored location for casting spells of all sorts, to be fair. The request for the “corpse daimon” to masquerade as a bath attendant to help with accomplishing a specific goal is unparalleled, though (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 132-133).

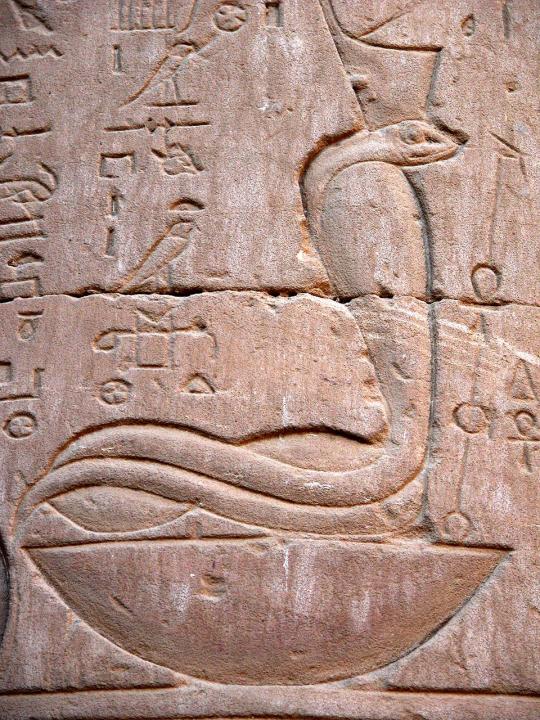

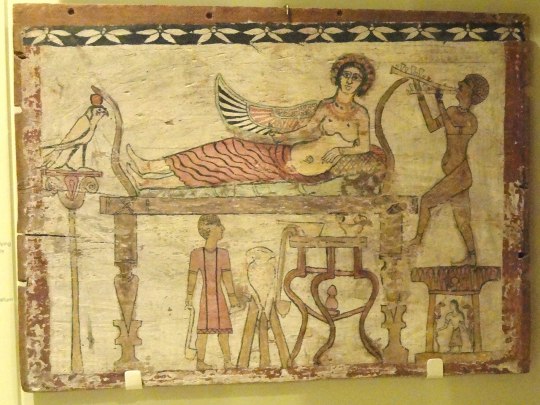

A combinative "Isis-Persephone" (or vice versa) from the late second century CE (Wikimedia Commons) As far as other appeals to supernatural entities go, it might be surprising to see Osiris mentioned in association with Persephone, Cerberus, the Erinyes and various elements of topography of the Greek underworld. It is presumed that this passage depends on the identification between him (as well as Serapis) and Hades, which is fairly well documented in Ptolemaic sources (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 146). However, it’s also worth pointing out that Persephone could serve as the interpretatio graeca of Isis, though it was by no means exclusive, and the latter could in various contexts or time periods be linked with Demeter, Cybele, Selene, Hecate, Aphrodite and others instead (Magical Hymns…, p. 9-10)

The unnamed “messenger” of Osiris is presumed to be Hermes, invoked not under his proper name but under a standard Homeric epithet. Referring to him as a “boy” most likely reflects the convention of depicting him as a child, which is attested through Hellenistic and Roman periods (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 146-147).

In addition to invoking a nameless corpse daimon and a number of deities, the spell uses a lot of voces magicae - magical formulas with no apparent meaning, sometimes the result of religious terms or even theonyms from langues other than Greek and Egyptian . Perhaps the most interesting inclusion among these is “Ereschigal”. This is obviously a derivative of Mesopotamian Ereshkigal, though as I outlined in my previous article, we’re essentially dealing with a ship of Thesus in this case; and if we are to take this as a reference to a specific deity rather than a hocus pocus formula, it’s best to think of it as an unusual epithet of Hecate as opposed to a conscious reference to a deity from a theological system otherwise basically entirely absent from Greco-Egyptian magic. The other interesting cameos are Azael and Beliam, a misspelling or variant form of Belial (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 144).

One last detail which requires some explanation is the reference to inflaming the liver, in addition to heart and soul. This is not a magical curiosity, but rather a reflection of a belief widespread all across the Roman Empire in the first centuries CE: the liver was believed to be the organ responsible for passions of various types. Invoking it alongside the heart in spells is well documented (Love Between…, p. 90).

Spell 3: the pronoun controversy

There might be a third lesbian spell. It is inscribed on two lead tablets from Panoplis, most likely from the second century CE (Love Between…, p. 90-91). The provenance was possible to establish based on the presence of the name Tmesios, “midwife”, which in Egyptian was written with the same determinative as the names of gods. It is most likely an euphemistic reference to Heqet, the goddess of midwifery, who was a very popular deity of Panoplis (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 116-117). The most recent edition I’m aware of is included in the Supplementum Magicum, vol. 1 (p. 116):

The text is undeniably a standard love spell. It even features an appeal to a corpse daimon - a certain Horion, son of Saropus - like the two discussed above (Love Between…, p. 91). The fact he is invoked by name is unusual - most corpse daimons are left anonymous (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 115). A further unique detail is the inclusion of a small drawing of a mummy - generally assumed to be Horion:

The supposed corpse daimon, via Supplementum Magicum vol. 1, p. 116; reproduced here for educational purposes only. An alternate proposal is that this is a symbolic representation of Nike being affected by the spell, as there are no other depictions of corpse daimons, and such entities are consistently described as mobile, which to be fair indeed doesn’t fit a mummy particularly well (Christopher A. Faraone, Four Missing Persons, a Misunderstood Mummy, and Further Adventures in Greek Magical Texts, p. 151-152). Still, unless further evidence emerges, there’s no reason not to stick to the consensus view.

Next to the mummy drawing, the other mystery is the reference to a period of five months. Why exactly would Nike be under the effect of the spell for that period of time remains uncertain (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 117). It might be a nod to the notion of “trial marriage”, which also lasted for five months. After this period, the parties involved would determine whether they want to formalize the relationship with a written contract or part ways instead (Love Between…, p. 107). However, by far the main topic of debate regarding the spell is the gender of Pantous/Paitous. While Nike bears an undeniably feminine name, the other name is not spelled consistently even on the tablets themselves, and has no other attestations. This also holds true for Gorgonia from spell #2, but in her case there’s no ambiguity - the name is undeniably feminine. However, -ous can be a suffix of both feminine and masculine names; while pa- occurs in Egyptian names as a masculine prefix. To make things more complicated, in both cases the relative pronoun referring to Pantous/Paitous is feminine - but it has been suggested that this is a typo due to presence of an incision on the tablet which might indicate the scribe made a typo wanted to actually write the masculine form. The gender of this person is thus difficult to determine (Love Between…, p. 93-94).

The assumption that we’re dealing with a double typo, according to the authors of the most recent translation, is supported by similar typos in other magical papyri, where the context makes it easier to ascertain the gender of the parties involved (Supplementum Magicum…, p. 117). Bernadette J. Brooten argues this is an overabundance of caution, though, since the spell under discussion is the only example where every single pronoun would have to be a typo. Furthermore, there are no other errors in the text (Love Between…, p. 95).

Brooten also offers an interesting solution to the uncertainty stemming from Pantous/Paitous’ name itself: even if it is masculine after all, its bearer might have been a woman who took on a masculine persona in some contexts, complete with a masculine name, or perhaps a nickname. She offers a precedent for this interpretation: the character Megilla/Megillos from Lucian of Samosata’s Dialogues of the Courtesans (Love Between…, p. 96). Since exploring this topic fully goes beyond the scope of the spells themselves, I will explore it in more detail in a separate section.

Part 2: WLWizards in context

From Plato to Lucian

In the fifth of Lucian’s dialogues a certain Leaina discusses recent events in her life with a friend. She is, as you can probably tell from the title of the whole work, a courtesan. At some point in the not-so-distant past she encountered a person who she refers to as Megilla, but who, as she stresses, at one point used the name Megillos in private. The character is AFAB, but for all intents and purposes presents masculinely - “like the most manly of athletes”, to be precise, as they describe it (Love Between…, p. 52). They engage in typically masculine pursuits, like holding symposiums, cut their hair short like young men (but wear a wig in public to hide that) and bring up that another character, Demonassa, is their wife in order to stress own masculinity (Andreas Fountoulakis, Silencing Female Intimacies: Sexual Practices, Silence and Cultural Assumptions in Lucian, Dial. Meretr. 5, p. 119-120). From a modern POV, it might appear that Megillos is a partially closeted trans man whose name is the masculine form of his deadname, but while this would be an obvious angle for a retelling to take, in reality the character is an example of a Greco-Roman stereotype of a woman attracted to women. Lucian refers to Megilla/Megillos as a hetairistria. He states that this rare term refers to women who pursue relationships with other women, and explains that this basically makes them like men (Love Between…, p. 23).

It’s important to stress we have no real evidence that this word - or any other ancient labels of similar sort - were actually used by any women to describe themselves (Love Between…, p. 7). Lucian most likely decided to use it as a nod to Plato (Love Between…, p. 53). The plural form, hetairistriai, is used to refer to women attracted to women in his Symposium (Love Between…, p. 41). It was most likely etymologically related to hetaira, in this context to be understood as something like “companion” (though it could also refer to a courtesan - as it does in the original title of Lucian’s work). It’s fairly rare in later sources, though dictionaries from the early centuries CE confirm it was understood as a synonym of tribas (plural: tribades), which was more or less the default term for women attracted to women in Greek, and later on as a loanword in Latin as well. An anonymous medieval Byzantine commentary on Clement of Alexandria, a second century CE Christian writer (more on him later) provides a second synonym, lesbia, which constitutes the oldest attested example of explicitly using this term to refer to a woman attracted to women, rather than to an inhabitant of Lesbos, though the context is not exactly identical with its modern application as a self-designation, obviously (Love Between…, p. 4-5). In Symposium the existence of hetairistriai is presented neutrally, as a fact of life - the reference to them is a part of the well known narrative about primordial beings consisting of two people each. Plato apparently later changed his mind, though, and in Laws, his final work, he condemns them as acting against nature (Love Between…, p. 41). It has been argued that the negative attitude might have been widespread in the classical period, though for slightly different reasons - it is possible that relationships between women would be seen as a transgression against the dominant hierarchy of power, on which the notions of polis and oikos rested (Silencing Female…, p. 113). As far as I can tell this is speculative, though.

While Plato’s rhetoric about nature finds many parallels in later sources - up to the present conservative discourse of all stripes worldwide (though obviously it is not necessarily the effect of reading Plato) - other arguments could be mustered to justify opposition to relationships between women as well. In one of his epigrams the third century BCE poet Asclepiades decided to employ theology to that end. He declared that the relationship between two women named Bitto and Nannion was an affront to Aphrodite; a scholion accompanying this text clarifies that they were tribades (Love Between…, p. 42). Note that I don’t think the fact that all three of the lesbian spells don’t invoke Aphrodite is necessarily evidence of the women who wrote or commissioned them adhering to a similar interpretation of her character, though - especially since they are separated by a minimum of some 500 years than the aforementioned source. While obviously we can’t entirely rule out that Asclepiades’ poem reflected a sentiment which wasn’t just his personal view regarding Aphrodite, it seems much more likely to me that the fact all three spells postdate the times when underworld deities and ghosts started to successfully encroach upon her role in this genre of texts is more relevant here. "Masculinization" and related phenomena

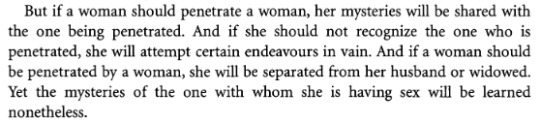

While clearly hostile, neither Plato’s nor Asclepiades’ works contain the tropes on which Lucian’s dialogue depended. What has been characterized by modern authors as “masculinization” of women attracted to other women only arose as a trend in literature after the rise of the Roman Empire, especially from the reign of Augustus onward (Love Between…, p. 42-43). This reflected the fact that Roman thinkers - as well as their Greek contemporaries - apparently struggled with grasping the idea of sex in which they couldn’t neatly delineate who is passively penetrated and who is actively penetrating. This resulted in the conclusion that surely one of the two women involved must have played the “masculine”, active role, and that sex between women must also have been penetrative. In some cases this involved confabulations about what some described in scholarship as an “some unnamed phallus-like appendage” (Love Between…, p. 6). A good example of an author wholly dedicated to this idea is the second century CE dream interpretation enthusiast Artemidoros. He evaluated sex between women as “unnatural” - a category in which he also placed oral, which he however saw as an act which by default had a man on the receiving end (Love Between…, p. 181). The sole passage in his opus magnum dealing with sex between women can be seen below (translation via Daniel E. Harris-McCoy, Artemidorus’ Oneirocritica. Text, Translation & Commentary, p. 149):

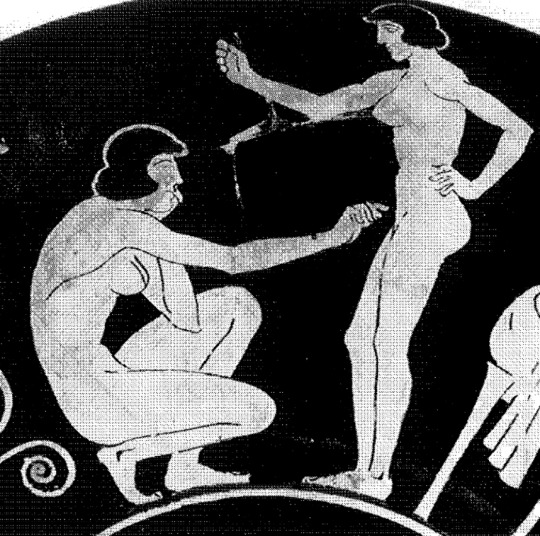

It needs to be pointed out here that earlier visual representations do not appear to be quite as fixated on this point. Evidence includes a Greek red figure vine vessel dated to 515-495 BCE or so decorated with a scene involving a woman touching another’s inner thigh and genitals; another slightly younger work of similar variety shows a kneeling woman reaching for another’s genitals, though it might depict depilation (contemporary sources indicate women plucked public hair by hand) rather than sex (Love Between…, p. 57-58). I must admit I really like the contemplative expression of the kneeling woman, which you can see on the screencap below (also available to view here):

Obviously, works of art such as the one above don’t necessarily reflect an ancient wlw point of view, and might very well be voyeuristic erotica which instead reflects what male painters presumed lesbian sex entailed. However, alongside a slightly bigger number of contemporary works possibly depicting couples in other situations they nonetheless make it possible to establish that the participants aren’t really differentiated from each other - in other words, they neither present differently, nor seem to be separated by age (Love Between…, p. 59).

Needless to say, it’s difficult to tell if either the older or the newer sources reflected actual trends in presentation among women attracted to women - with small exceptions, like the spells this article ultimately focuses on, we have next to no texts actually composed by them or for them, and the same caveat applies to visual arts. The majority of sources we are left with were, as you can probably already tell based on the sample above, written by men who at the absolute best considered them immoral (Silencing Female…, p. 112-113). For this reason, evaluating whether Lucian’s Megilla/Megillos is entirely literary fiction or merely a mocking exaggeration, and by extension whether she can be used as an argument in discussion about the identity of Pantous/Paitous from the third spell, is difficult at best.

For what it’s worth, an anonymous physiognomic treatise from the fourth century does mention that there are “women who have sex with women whose appearance is feminine, but who are more devoted to masculine women, who correspond more to a masculine type of appearance”, but further passages in this work would indicate that this might be yet another case of stereotyping rather than a nuanced account of varying presentation (Love Between…, p. 56-57). One specific aspect of Megilla/Megillos' character appears to match a single other source as well. Claudius Ptolemy, a second century astronomer and astrologer, offers a twist on the stereotype relevant to his primary interests. He states it is one of the “diseases of the soul” in his Tetrabiblos. He characterizes it as a result of a specific combination of constellations and planets (a term which in this context also encompassed the sun and the moon) at the time of an individual’s birth. Based on the specific scenario, women might become tribades - which according to Claudius Ptolemy means behaving in a masculine manner and pursuing relationships with other women secretly or openly, with the most extreme possible configuration resulting in a propensity to refer to another woman as one’s “lawful wife” (Love Between…, p. 124-126). Once again, it’s not really possible to determine if this reflects a genuine convention - though it does more or less parallel how Megilla/Megillos describes her partner. Evaluating how accurate the available sources are is made even more difficult by the fact that the “masculinization” was often paired with other literary devices meant to cast relationships between women as an “alien” or immoral phenomenon. Quite commonly they could be described as something utterly foreign or anachronistic, as opposed to a part of everyday life in contemporary Rome (Love Between…, p. 42-44). The second century writer Iamblichos, author of the lost Babyloniaka, or at the very least the popularity of his work in antiquity, arguably represents an example of this phenomenon. On the moral level, Iamblichos considered love between women “wild and lawless”, though he simultaneously had no issue writing about it, one would assume for voyeuristic purposes. His novel is only known from a summary preserved by the Byzantine patriarch Photius, but apparently enjoyed a degree of popularity earlier on. It described an affair between Berenike, a fictional daughter of an unspecified ruler of Egypt (fwiw, multiple women from the Ptolemaic dynasty bore this name), and a woman named Mesopotamia (sic), and their eventual marriage (Love Between…, p. 51). In contrast with the other, more famous Babyloniaka by Berossos, no primordial fish people or sagacious rulers with unnaturally long life spans make an appearance. A daring project to combine the two has yet to be attempted. Jewish and Christian reception

The Greco-Roman condemnations of relationships between women was also adopted in early centuries CE by Jewish and Christian writers. In the former case a notable example is the Sfira, a rabbinic theological commentary on Leviticus composed at some point before 220 CE. The passage dealing with 18:3 - “You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt (... )and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan” - asserts that marriages between women were a custom among Egyptians and Canaanites. This is unlikely to be a faithful ethnographic report; rather, something perceived negatively is attributed exclusively to foreigners (Love Between…, p. 64-65). As far as Christian sources go, pretty similar rhetoric can also be found in Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (Love Between…, p. 64). Another notable early Christian author to adopt similar views was Clement of Alexandria, whose condemnations combined quotations from Paul’s letter, the apocryphal Apocalypse of Peter (which he viewed as canonical), and a host of Greek and Roman philosophers, most notably Plato - as you can guess, specifically the passage from Laws which already came up earlier (Love Between…, p. 320-321). He dedicates a lot of space to condemning marriages between women, which he describes as an “unspeakable practice” amounting to women imitating men (Love Between…, p. 322). It’s a part of a longer diatribe against even the slightest hints of gender nonconformity, which also condemns, among other things, men who shave their facial hair (Love Between…, p. 323-324). There’s a lot of other smash hits in Clement’s work, including an extensive section focused on, to put it colloquially, theological considerations about cum, very creative mixed religious-zoological approach to the digestive system of hares, as well as some more “mundane” but still pretty chilling apologia for domestic abuse, which I will spare you from. For an author from Alexandria, he also seems oddly ignorant about Egyptian sources, as at one point he claims that the fact Egyptians worship animals puts them morally ahead of Greeks, because animals do not commit adultery. I am sorry to report that adultery between Egyptian gods is, as a matter of fact, directly referenced in the magical papyri, which are roughly contemporary with Clement - specifically in PGM IV 94-153 (The Greek…, p. 39):

Concluding thoughts The sources discussed above are mostly supposed to illustrate that while it’s possible to study the prevailing attitudes among the contemporaries of the “protagonists” of the spells, it’s not really easy to say what their private lives were like. We don’t know how open they were about their preferences; how they presented; what, if any, label they used to refer to themselves. We can’t even ascertain if any of them were ever actually in relationships with other women, and whether the norm for women like them - if such norms even existed - was to pursue brief trysts or commitment for life, in parallel with aims of the authors of at least some of the heterosexual love spells (Love Between…, p.105-107).

In what after almost 30 years remains, as far as I am aware, the single publication with the most extensive discussion of the spells, Bernardette J. Brooten argued that since marriages between women are mentioned in five sources roughly contemporary with them - by Lucian of Samosata, Clement of Alexandria, Claudius Ptolemy, Iamblichos, and in the Sifra - they must have been an actually observed custom in Egypt in the early centuries CE. She argues that since marriages were basically personal legal agreements, it theoretically wouldn’t be impossible for two women to pursue such a solution (Love Between…, p. 66; note the fact the Sfira also refers to marriage between women as a Canaanite custom, which no primary sources from any period corroborate, is not addressed). I don’t think her intent was malicious, but I must admit I’m skeptical if it’s possible to reconstruct much chiefly based on sources which, as you could see in the previous section of the article, are mocking at best and openly hostile at worst, and a small handful of actual first hand testimonies which due to their genre sadly provide very little information. Sadly, we ironically can tell more about how the women from the spells thought corpse daimons functioned than how they envisioned the relationships they evidently desired.

To illustrate the difficulties facing researchers, imagine trying to reconstruct what the life of the average lesbian in the English-speaking world in the 2010s would be like with your sole points of reference being a single episode of a Netflix show with a mildly offensive gender nonconforming character, a press article written by an eastern European priest ranting about “gender ideology” imported from abroad corrupting children, a fanfic written by a homophobic weeb who jacks off to lesbian porn, and a small handful of contextless blog post actually written by wlw, but not necessarily entirely focused on anything related to her identity. The results wouldn’t be great, I’d imagine. The sources mustered by Brooten ultimately aren’t far from that, I’m afraid (I leave it as an intellectual exercise for you to determine which of the satirical modern comparisons applies to which) - thus it’s difficult for me not to see her conclusions as perhaps leaning too far into the direction of wishful thinking. But, in the end, wishful thinking is not innately bad - I’d be lying if I said I don’t have a host of personal hypotheses which fall into the same category (one of these days I will explain why I think a “don’t ask, don’t tell” attitude doesn’t necessarily seem incompatible with Old Babylonian morals). Therefore, even though I’m more skeptical if the “protagonists” of the texts this article revolved around could truly pursue relationships on equal footing with other inhabitants of Roman Egypt, I can’t help but similarly hope that they found at least some semblance of happiness in the aftermath of the endeavors documented in the discarded magical formulas.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hecate, Melinoe, "Ereschigal": when a name becomes the ship of Theseus?

(Triple Hecate on a magical apparatus from Sardis, via William Bruce and Kassandra Jackson Miller, Towards a Typology of Triangular Bronze Hekate Bases: Contextualizing a New Find from Sardis, p. 512; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

This article wasn’t planned in advance. It’s largely a side effect of trying to help a friend with tracking down a \specific source, the elusive reference to Melinoe from outside the Orphic Hymns, in order to determine whether it really treats her as interchangeable with Hecate. Investigating this topic revealed that it’s connected fairly closely with something I wanted to cover for a while already, namely the Greek (or rather Greco-Egyptian) magical papyri, a unique text corpus to a large degree focused on Hecate and in particular on supposed equations with a number of other figures, ranging from Selene, though Isis, to Mesopotamian Ereshkigal. The last of these cases is what I will focus on, as similarly as the supposed interchangeability of Hecate and Melinoe it is often presented online without context. While the two core goals of this article are establishing whether Melinoe really is just Hecate, a distinct but very Hecate-like figure, or something in between, and explaining whether references to “Hecate-Ereschigal” necessarily indicate some greater degree of familiarity with Mesopotamian theology, that’s not all I will cover. You will also be able to learn why Hecate gained an extra body in early centuries CE; whether it’s true that sources referring to her as genderfluid exist; which unexpected figure plays the role of messenger of Zeus in magical papyri; what the possible last known pre-modern reference to Ereshkigal has to do with Jewish angelology; and more!

Note that technically this is not my first Hecate article; I wrote one long ago - in the early days of this blog, probably around half a decade ago at the height of the initial covid lockdowns, if not in the even more distant past. However, it was subpar; for all intents and purposes, this is the first one which meets my modern standards.

The case of Melinoe

Melinoe appears in a very small number of sources, all of which are fairly well studied. In theory this makes her fairly easy to write about. However, she is also fairly unique in that I can’t think of many other mythological figures who arguably received an enormous boost in prominence specifically thanks to their online reception. This is a double edged sword. On one hand, unique sources reach more people than they would otherwise, at least indirectly.. On the other, misconceptions and misreadings are abundant. For this reason, a brief introduction to her will be necessary before evaluating what, if any, connection existed between her and Hecate.

There’s no strong reason to suspect Melinoe was ever particularly popular in antiquity - more on that soon - and she had negligible presence in art before quite recently. A notable exception is apparently an offhand reference to her in one of Hugo Grotius’ poems (Edwin Rabbie, Editing Neo-Latin Texts, p. 42). I was sadly unable to track it down - if you want to check for yourself, it is reportedly to be found on p. 359 in the 1992 anthology Original Poetry 1604–1608 (De Dichtwerken van Hugo Grotius, I 2 A/B 4).

Melinoe in the Orphic Hymns

Grotius relied on what was the only source about Melinoe available to him and his contemporaries - the Orphic Hymns. They remain a pretty important point of reference for researchers today, though not exactly due to the presence of Melinoe. Even though they’re relatively late and fairly esoteric (as expected from an orphic text corpus), they’re one of the best preserved collections of Greek hymns which were undeniably performed in a religious setting. We don’t know the full history of their transmission, though. They were hardly discussed in other literature before the fifteenth century, barring a single reference in a commentary on Hesiod’s Theogony which might date to the thirteenth (Daniel Malamis, The Orphic Hymns. Poetry and Genre, with a Critical Text and Translation, p. 1).

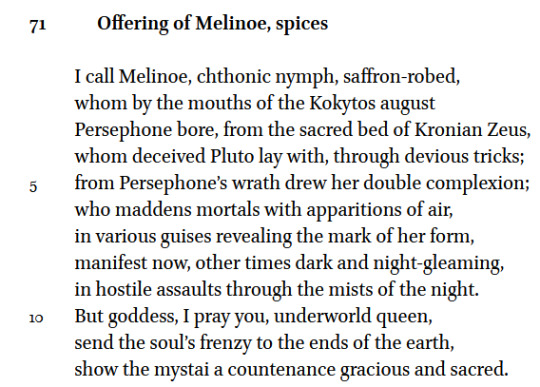

The full collection consists of eighty eight hymns, each dedicated to a different deity, ranging from major figures recognized virtually all over the at least partially Hellenized world, through personified abstract concepts, to local deities from the west of Asia Minor with few, if any, other attestations. Melinoe belongs to the last of these categories, alongside the likes of Mise, Hipta and Erikepaios (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 171-172). The seventy first hymn is dedicated to her. Multiple translations are available, the most recent one is Daniel Malamis’ (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 103):

The exact translation of some phrases remains a subject of heated debate, but the gist of it is fairly well understood: Persephone gives birth to a minor underworld goddess after Zeus impersonated Hades to seduce her. A minority position is that Melinoe somehow has two biological fathers (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 130). I’m not aware of any translator making it even remotely possible that Hades alone was her biological father - this is entirely an online misconception. There is no alternate account of her origin, the hymn is the only version - claims on the contrary are doubtlessly the result of online games of telephone. The friend whose Melinoe inquiry was a catalyst for this article informed me that there are online claims that the myth describes Hermes witnessing this event. It’s important to stress that nothing of that sort is evident here, as you can see for yourself - the only deities mentioned are Melinoe herself, Persephone, Zeus and Hades. I’d assume this misconception is the result of the river Cocytus also being mentioned in the hymn to Hermes Cthtonios (and nowhere else in the Orphic Hymns), which however doesn’t deal with Melinoe, let alone specifically with her birth (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 89):

To go back to the main topic, dedicating a lot of space to explaining the origin of Melinoe sets the hymn apart from the other eighty seven. It is possible that the compiler considered her obscure to the point it warranted explaining to their audience who she was by narrating her origin myth (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 266). As a result of this unusual focus, she receives very few epithets compared to most other deities praised in the Orphic Hymns. She shares this status with Nomos - in whose case the small number of epithets instead reflects the fact he was more a personified concept than a deity proper, though (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 270).

Thanks to the contents of the hymn, despite Melinoe’s obscurity we have a pretty solid idea about her character, too. At the very least for the compiler of the hymn, she was an appropriate deity to invoke to guarantee safe passage of the dead into the afterlife (Kassandra Jackson, ‘She who changes’ (Amibousa): a Re-examination of the Triangular Table from Pergamon, p. 465). Further insights might possibly be gained from her name, which has been variously interpreted as “gentle-minded” (from meilinói; this interpretation was seemingly proposed as early as in the sixteenth century, as evidenced by an anonymous translation into Latin explaining her name as placidae mentis) or “russet” (from mílinos), in this context a poetic way to describe the color of the moon (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 288).

The fact the hymn refers to Melinoe as a nymph warrants some further discussion as well. I haven’t seen this point raised in literature, but this would fit neatly with her presumed status as a minor goddess of strictly local importance. It was not uncommon for such figures to be labeled as nymphs when they were incorporated into the broader “Olympian” pantheon in one way or another, as attested for example for Callisto or Britomartis (Jennifer Larson, Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore, p. 7).

A potential issue for this interpretation is that Melinoe doesn’t seem to correspond to any specific natural feature, though - the localized character of nymph cults reflected the fact that they typically corresponded to a specific river, mountain, island, et cetera (Greek Nymphs…, p. 9). Alcman mentions underworld nymphs (lampads) from the entourage of Hecate, but this reference is entirely isolated (Greek Nymphs…, p. 284; note the wikipedia article asserting they are referenced in Hesiod’s Theogony is essentially a hoax, though admittedly a fun, creative one). For what it’s worth, the term “nymph” might very well just be used metaphorically to indicate Melinoe was imagined as a young woman, though (Anne-France Morand, Études sur les Hymnes Orphiques, p. 182).

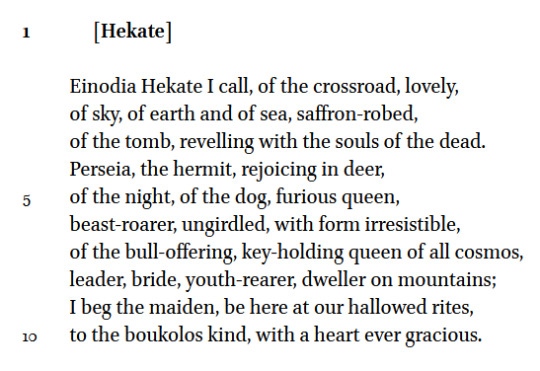

Nymph-centric deliberations aside, the fact that the hymn associates Melinoe with ghosts and more broadly with the underworld, and that she might even have an indirect lunar connection depending on which etymology of her name is correct, it probably doesn’t come as a surprise that it’s pretty much the academic consensus that overall her character was Hecate-like (though pretty obviously less multifaceted). The similarities even extend to terms used to refer to them (“saffron-robed” is a fairly common epithet of Hecate) and requests aimed at Melinoe in the hymn and at Hecate elsewhere (‘She who changes’ …, p. 465). However, as far as the Orphic Hymns are concerned, they are ultimately two separate goddesses (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 361). In the hymn dedicated to her, Hecate is actually portrayed as a veritable head of the pantheon (The Orphic Hymns…, p.165-166), directly addressed as the “queen of all cosmos” (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 27):

Ultimately it’s important to bear in mind that even if the compilers clearly cared about Melinoe enough to dedicate a separate hymn to her, they neither equated her with Hecate nor even attributed a comparable degree of importance to them. The investigation cannot end here, though. Melinoe has exactly one more further attestation.

Hecate-Melinoe, Hecate-Persephone, Hecate-Zagourê? The Pergamon tablet and its historical context

An illustration of the triangular magical tablet from Pergamon (wikimedia commons)

In addition to her considerably more famous role in the Orphic Hymns, Melinoe also makes a cameo on a peculiar object from Pergamon (The Orphic Hymns…, p.172). It dates to the third century CE. In contrast with the hymns, it doesn’t provide much mythological or theological information about her. It’s not even really a proper text. Rather, it’s a triangular tablet inscribed with a long series of epithets of Hecate, arranged into three columns under three depictions of her placed in the corners (‘She who changes’ …, p. 457).

In this context, Melinoe is explicitly one of Hecate’s (many) names (‘She who changes’ …, p. 464-465). This is presumed to reflect a level of familiarity with both figures sufficient to establish they were similar enough to warrant an equation (Richard Gordon, Another View of the Pergamon Divination Kit, p. 198). It’s also worth noting that Melinoe’s presence in the inscription was one of the arguments which lead to the formation of the generally accepted view that the Orphic Hymns must have been originally composed somewhere in the proximity of Pergamon, at least more broadly in western Anatolia (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 171-174).

This doesn’t mean we should conclude the Orphic Hymns were also written with the same arrangement in mind, though. Equation in a specific context doesn’t mean two figures can be considered interchangeable. It’s hard to think of better proof than the fact not only Melinoe, but also Persephone is reinterpreted as a title of Hecate on the Pergamon tablet (‘She who changes’ …, p. 466). It’s hardly the only magical text to do so (Eleni Pachoumi, The Concepts of the Divine in the Greek Magical Papyri, p. 130-131). It is probably relevant that a tradition in which Hecate was a daughter of Demeter is also attested - sparsely, but still. It might even be alluded to in Eurypides’ Ion, where Enodia is addressed as such (Ljuba Merlina Bortolani, Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt. A Study of Greek and Egyptian Traditions of Divinity, p. 232).

Hecate actually gets a fair share of other names which usually would refer to independent figures on the discussed tablet; the two cases discussed above aren’t unique in that regard. Some of the other notable examples include Leukophryne (“of the gleaming brow”), a designation used exclusively for the local form of Artemis worshiped in Magnesia on the Meander; Dione (sic); and even the angel Zagourê (“he whose fire glows), best known from the Eighth Book of Moses and other magical papyri, a genre of text I will soon go back to (‘She who changes’ …, p. 463-466).

While as far as I am aware the last equation is unique, as a curiosity it might be worth noting that the words angele and angelos were actually sometimes used to describe Hecate elsewhere (for example by Hesychius), usually in the literal sense, to reflect moving between the underworld, the earth and Olympus (Rangar Cline, Ancient Angels. Conceptualizing Angeloi in the Roman Empire, p. 49). It’s tempting to speculate that perhaps this is why the author of the Perhamon tablet opted to equate her with a specific angelos they were vaguely familiar with - it’s not like the text preserved any distinct information about Zagourê’s character.

The Pergamon tablet isn’t unique - similar objects also inscribed with long series of Hecate names are known from Sardis and Apamea (Towards a Typology…, p. 509) - but as they don’t mention Melinoe I won’t discuss them here in detail. All three of these extensive collections of Hecate names reflect the same phenomenon, though. In late antiquity Hecate’s defining feature was arguably being “many-named” and “many-formed” (The Concept…, p. 137). It’s tempting to assume that the standard three bodied Hecate depictions, which the average person would be well familiar with, made her particularly suitable for equations with goddesses who shared some of her characteristics - which, as I outlined above, is definitely the case for Melinoe.

It's also important to stress that there was a pretty universal religious anxiety over getting the names and titles of deities wrong or omitting an important one, though. Simultaneously, it was believed that it pleases a deity to hear many of them, say, in a hymn in their honor; and, furthermore, that they could be compelled to act by sufficient familiarity with their names (The Orphic Hymns…, p. 218-219). It’s easy to imagine how this would influence composition of texts focused on a goddess whose very nature required turning this focus on names and titles up to eleven. Given that Melinoe is not attested on any other similar artifact, perhaps she was included just in case due to such a concern? Ultimately this is pure speculation on my part, though, and it’s equally if not more plausible that she is included only in this one list simply because she was exclusively worshiped relatively close to where it was found.

The long strings of names and magical formulas on the Pergamon tablet and other similar objects are also significant for a further reason: they make it possible to establish a connection with a specific corpus of Greco-Egyptian esoterica, the late antique magical papyri. The owners of the tablets were not necessarily actually well versed in Egyptian religious texts of the sort passed down in temple scriptoriums, but it does seem they knew enough about them to attempt to use the same principles - which is reflected, among other things, in the long strings of names assigned to Hecate (Another View…, p. 197-198). Melinoe is not attested in any of these texts (‘She who changes’ …, p. 465), and her role in this article as a result ends here.

Before I can move on to the second case of a peculiar link between Hecate and another deity I'd like to discuss, a brief introduction to the magical papyri themselves will be necessary.

A brief introduction to magical papyri

“Greek magical papyri” and “Papyri graecae magicae” (PGM) are the modern conventional names designating a corpus of unusual texts from, as you can probably guess, Egypt.

The earliest example known dates to the fourth century BCE, but most are significantly younger (Jacco Dieleman, The Greco-Egyptian Magical Papyri in Guide to the Study of Ancient Magic, p. 316). While they were composed under Roman rule, between the second and fifth centuries CE, the only languages used in them are Greek, and less commonly Demotic, with no trace of Latin. This is pretty much in line with other texts from Roman Egypt. It was culturally Hellenized through the period of Ptolemaic rule, but it never really became Romanized to a comparable degree, and Latin was restricted to military administration (Magical Hymns…, p. 3-4).

Why are these papyri “magical”? Despite involving deities and frequently referencing specific myths, they generally describe rituals which took place in private houses, as opposed to temples. The stated aims often can be only described as petty (securing the love of another person, gaining material wealth, or even a specific outcome in a chariot race…), and require some rather unorthodox solutions, like quite literally blackmailing deities, ghosts or other supernatural beings. Many of the texts also stress that their contents should remain secret. Thus, referring to them as “magical” rather than broadly “religious” literature is seen as optimal by researchers, to stress that they don’t represent the official temple cults, but rather a distinct sphere of activity (Magical Hymns…, p. 14).

It needs to be pointed out that modern terminology reflects the Greek (and Roman) outlook more than Egyptian. The closest Egyptian term to “magic”, heka (ḥkȝ) originally referred to something that was ultimately a prerogative of temple priests, rather than an unofficial application of religious principles to private ends (Magical Hymns…, p. 16-18). Since at least some of the authors of the magical papyri were Egyptian priests, possibly ones who sought new sources of income in changing times (Magical Hymns…, p. 23-24), it is possible that they deliberately reinvented their practices for a new clientele to meet their expectations (Magical Hymns…, p. 19). It was pretty clearly important to make sure the clients were satisfied - at least some of the texts were composed ad hoc for specific unique cases (Magical Hymns…, p. 277). While the magical formulas were innovative and had no direct antecedents, they were deliberately presented as a secret ancient tradition to imbue them with more authority. Sometimes they were outright claimed to be passed down from famous historical authors or religious figures, ranging from Pythagoras, through Manetho, to Moses, or even deities, typically ones heavily associated with magic like Hermes or Isis (The Greco-Egyptian…, p. 312-313).

The magical papyri feature a plenty of unusual technical terms known as voces magicae. They’re magical formulas with no actual meaning which in the context of the magical papyri might have been treated as secret names of deities. While it is possible some of them were garbled transcriptions of words originating in Egyptian or in Semitic languages, many are pure gibberish, like sequences of vowels (aeēiouō is a genuine example) or invented palindromes (The Greco-Egyptian…, p. 285). The formulas sometimes label the voces magicae as Hebrew, Aramaic or Meriotic, but this is obviously not true - at best, it can be assumed that to the customers of the experts preparing the magical papyri they sounded sufficiently “alien” for these labels to be believable (The Greco-Egyptian…, p. 309-311). Some authors of the papyri evidently went even further, and claimed that the abra cadabra formulas represent the language of animals, for example falcons or baboons (The Greco-Egyptian…, p. 311-312):

The case of “Ereschigal”

It probably comes as no surprise that most of the deities frequently invoked in the magical papyri are Greek (Helios, Hermes, Hecate, Selene, etc.), Egyptian (Isis, Osiris, Seth, Bes, etc.) or, like Serapis, somewhere in between (The Concepts…, p. 10). What is less obvious is why a few of them contain references to Mesopotamian Ereshkigal - or rather “Ereschigal” (Ἐρεσχιγὰλ), to remain true to the Greek spelling. In a single case a Demotic form is attested, but it reflects the Greek one, and doesn’t represent an independent borrowing from any language spoken in Mesopotamia (Daniel Schwemer, Beyond Ereškigal? Mesopotamian Magic Traditions in the Papyri Graecae Magicae, p. 67). What is perhaps even more surprising is that her name is effectively treated as a byname of Hecate - one of the spells is directly labeled as directed towards “Hecate-Ereschigal” (The Concepts..., p. 21).

A crash course in Ereshkigal’s career, from Early Dynastic Lagash to Seleucid Uruk

Ereshkigal is a well attested deity, with a fair share of up to date publications dealing with her to booth. Sadly, as I’ve noticed while working on this article there’s a fairly significant issue with coverage of her in literature dealing with the magical papyri. In many cases even the authors of the most recent, rigorous publications in this field often seem to be far behind when it comes to Assyriology, and depend on and recommend questionable old scholarship. For instance, while I recommend Magical Hymns from Roman Egypt overall - it’s all over this article as a source, and I had a blast reading it - I really think it’s not ideal to use “Kramer 1960” (let alone “Wolkstein and Kramer 1981”) as the main points of reference. For this reason, I feel obliged to at least briefly discuss her history and character here. By the time Ereshkigal got to appear in the magical papyri, she was already a figure with a remarkably long history. She is attested in the textual record for the first time in an offering list from the reign of Urukagina, an Early Dynastic king of Lagash, from around 2370 BCE or so. The even earlier textual sources, like god lists from Fara and Abu Salabikh or the Zame Hymns, don’t mention her at all, though (Dina Katz, The Image of the Netherworld in the Sumerian Sources, p. 386).

Lu-Utu’s inscription on a dedicatory cone among other similar objects (British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only) While Ereshkigal’s very name - “queen of the great earth” - is probably intended to hint at her role as the queen of the underworld, the first text which explicitly characterizes her as such is an inscription of a certain Lu-Utu. He served as the governor of Umma in the Sargonic period (ca. 2300 BCE), probably between the reigns of Manishtushu and Naram-Sin (The Image…, p. 355).

There are actually no other known dedicatory inscriptions mentioning Ereshkigal, Lu-Utu’s is one of a kind (The Image…, p. 352). Overall her cult evidently had a small scope, and later attestations of offerings made to her, let alone sanctuaries dedicated to her, are uncommon (Frans Wiggermann, Nergal A in RlA vol. 9, p. 220). She is also absent from theophoric names, which makes her an outlier even as far as underworld deities go. However, it’s possible that the likes of Nergal or Ninazu would be primarily invoked in this context as the tutelary gods of their cities, not lords of the underworld (Wilfred G. Lambert, Lugal-edinna in RlA vol. 7, p. 137). The bulk of attestations of Ereshkigal are literary texts, chiefly from the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000-1600 BCE) and the Neo-Assyrian period (911-612 BCE).

As far as I am aware, there is only one notable cuneiform text corpus dealing in any capacity with Ereshkigal which have some temporal overlap with the (early) magical papyri - the administrative texts from Seleucid Uruk. They mention the existence of a “temple of Ereshkigal” in the city, though this term might actually refer to a cemetery, not a temple - or at least to a sanctuary directly connected to a graveyard (Julia Krul, “Prayers from Him Who Is Unable to Make Offerings”: The Cult of Bēlet-ṣēri at Late Babylonian Uruk, p. 74). Interpreting the term as something more than just an elaborate synonym for a graveyard is the easiest way to explain references to sacrifices made to Ereshkigal, though. These are at the very least implied by a set of instructions pertaining to daily offerings, according to which she couldn’t receive beef or fowl; in contrast with the other regulations (it is self-explanatory why Ningublaga, a cattle god, would be displeased to receive beef) the underlying logic remains unclear (Prayers from…, p. 62). However, even then, it was not really Ereshkigal herself who was actively worshiped - rather, it was her scribe Belet-Seri who enjoyed newfound popularity in Seleucid Uruk (Prayers from…, p. 76-77). Ereshkigal most likely was seen as an unapproachable, distant figure, just like before, and as such was hardly worshiped directly (Prayers from…, p. 75).

Julia Krul argues that Ereshkigal’s presence in the pantheon of Seleucid Uruk reflected diffusion of earlier knowledge about her status as Inanna’s sister, courtesy of the loose Neo-Assyrian adaptation of Inanna’s Descent (Prayers from…, p. 75). I’m skeptical myself - as pointed out by Alhena Gadotti, the term might very well be used as an honorary title, not necessarily as an indication of actual kinship (‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’ and the Sumerian Gilgamesh Cycle, p. 13). No independent evidence for the existence of such a tradition exists, and the very same myth has ample evidence for use of kinship terms as titles - Ninshubur refers to three separate gods as “father” despite none of them ever being actually viewed as her family. It’s also worth pointing out that in Nergal and Ereshkigal Ereshkigal is addressed as the sister of all of the gods when an invitation is sent to her, which obviously can’t be literal. This is ultimately a digression; I plan to go back to this point in a separate article eventually, though - consider this a teaser.

Putting abstract considerations aside, to sum up Ereshkigal didn’t offer a very good parallel to Hecate, not least simply because she was not exactly commonly worshiped - while Hecate is arguably attested primarily in the sphere of cult. Furthermore, while she does appear in Mesopotamian magical texts (āšipūtu), she doesn’t play a particularly major role in them (Beyond Ereškigal…, p. 67), and in contrast with deities such as Ea as Ningirima she was hardly a “deity of magic”. You probably could make an argument that if anything Ereshkigal offers a closer parallel to Hades - in the god list An = Anum a mini-section even lists names which did double duty both as her bynames and terms for the underworld (Wilfed G. Lambert, Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p. 24); the most notable example is easily Irkalla (An = Anum..., p. 196). However, as I’ll try to demonstrate in the next section, the matter of interpretatio graeca is not quite as simple as “the character of these two overlaps, so they ought to be analogous”.

Some notes on interpretatio graeca

Interpretatio graeca is a tricky subject in its own right. Equivalencies weren’t necessarily recognized universally. It goes without saying the perspective of Greeks and foreigners could vary considerably, too. For example, to Greeks the Lycian and Lydian goddess Maliya (Malis) was simply a nymph, as evident in her portrayal in Theocritus’ Idylls (Annic Payne, Native Religious Traditions from a Lydian Perspective, p. 242). However, both to Lycians and Lydians she was a counterpart of Athena - partially due to shared association with craftsmanship, partially because the Lycian kings wanted to emulate Athens politically in one way or another, and sought to portray their tutelary goddess as Athena-like (Eric A. Raimond, Hellenization and Lycian Cults During the Achaemenid Period, p. 153-154; Native Religious…, p. 241).

Oxus depicted in the form of Marsyas (wikimedia commons) Equations could be made based on very superficial similarity. For example, in Bactria a river god regarded as the head of the local pantheon, Oxus, came to be associated with Marsias (sic), and was depicted under the guise of the latter. This was the result of a random twist of fate - Greeks settling in Bactria after the conquests of Alexander largely came from Magnesia (Mary Boyce, Frantz Grenet, A History of Zoroastrianism, vol. III: Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman rule, p. 180; Boris A. Litvinskii, Igor R. Pichikian, The Hellenistic Architecture and Art of the Temple of the Oxus, p. 57-58). Since Marsias was the namesake river god of the main river flowing through this area, he was effectively THE river god to them - and thus upon encounter with a different river god a transfer of iconography was possible. The fact the two shared few, if any, characteristics otherwise was of no importance. Needless to say, nobody ever recognized Marsias himself as king of the gods; but his river-related lore was sufficient for his iconography to be borrowed.

A possible Hellenistic depiction of Nanaya (wikimedia commons) This case is still not quite as outlandish as the official Seleucid policy of recognizing Nanaya as the counterpart of Artemis, which is yet another example of politically motivated interpretatio. There’s an obvious difference right off the bat - Nanaya was associated with eroticism first and foremost, Artemis demonstrably… wasn’t; the same goes for her association with hunting, a sphere of influence Nanaya had nothing to do with. The lack of similar traits was of no real concern, though - Seleucids simply needed local deities who could be presented as counterparts of their dynastic triad of Zeus, Apollo and Artemis. Marduk as a typical pantheon head made a decent fit for Zeus (despite lack of any real connection to the weather), Nabu as his son and, broadly speaking, a deity linked to the arts (primarily scribal, but hey, close enough) was proclaimed the counterpart of Apollo (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Nabû and Apollo: The Two Faces of Seleucid Religious Policy, p. 20)… and Nanaya, as a Nabu-adjacent goddess, got to be Artemis (Nabû and Apollo…, p. 27). The fact Apollo and Artemis were siblings, while Nabu and Nanaya were not, was not an issue. It’s probably down to chance that it was Nanaya and not Tashmetum, who had a stronger and older claim to an association with Nabu who got this role, really - not that Tashmetum would be a much better match character-wise.

In particularly extreme cases it’s hard to attribute specific cases of interpretatio graeca to anything but confabulation about a deity one Greek author or another had only the vaguest idea of. Perhaps most notably, Herodotus (in)famously asserted that Persian Mitra was Aphrodite in a passage where he generally makes many claims about her foreign equivalents and moe broadly on foreign cults which make at best limited sense (Albert F. de Jong, Traditions of the Magi. Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature, p. 107-110). His mistake was repeated by Ambrosius, but to be entirely fair to Greeks and Romans, those two are outliers in this case, and other authors (notably Strabo and Nonnus, but not only them) were at the very least aware that Mithra was a male solar deity and/or that he presided over oaths, even if some of them were confused if he was Persian or Mesopotamian (Traditions of…, p. 286-288).

A unique problem with Hecate and interpretatio graeca is that in many cases we can’t really say much about the deities she was associated with in that capacity, which makes it difficult to determine what shared qualities or historical circumstances lead to the development of a close association. The likes of Roman Trivia or Thessalian Enodia are not exactly well represented in the historical record, to put it very lightly; they’re effectively epithets more than distinct deities which can be discussed in any meaningful capacity. There’s also the even more extreme case of Lydian Nenenene (sic). It’s not hard to find the assumption she was associated with Hecate in scholarship (ex. The Concepts…, p. 132), though the only evidence available is a partially preserved stela with a dedication to her found in Kula. The modern assumption rests entirely on the goddess preserved on it appearing distinctly Hecate-like thanks to the presence of a dog next to her, as no other attestations of Nenenene are available (Eda Nalan Akyürek Şahin, The Cult fo Hecate in Lydia: Evidence from the Manisa Museum, p. 38).

Ereschigal: deity, epithet, vox magica?

At first glance, even taking the difference in their respective characters, the case of Ereshkigal and Hecate might appear easier to parse just because the latter is pretty obviously nowhere near as ephemeral as Enodia or Nenenene. However, in reality the available information about her reception is at best troublesome to interpret.

Ereshkigal is not attested in Greek literature at all outside of the magical papyri and related objects, such as curse tablets and apotropaic gems (Magical Hymns…, p. 236). No cultic activity involving her is attested in areas where any of them were found (Korshi Dosoo, Magical Names: Tracing Religious Changes in Egyptian Magical Texts from Roman and Early Islamic Egypt, p. 123). To make it all even more complicated, not even once does the name appear in a context which would indicate any familiarity with Mesopotamian sources going beyond the awareness that Ereshkigal was an underworld deity. No epithets, no references to motifs from Mesopotamian literature, virtually nothing. When specific attributes are listed, they’re invariably those of Hecate or Persephone (Beyond Ereškigal…, p. 66-67).

Of course, it is clear that at least the initial stage of transfer must have involved people who possessed some basic familiarity with the structure of the Mesopotamian pantheon, After all, even if none of the attributes are Ereshkigal’s, and no text where the name appears shows any familiarity with specific Mesopotamian myths or with Mesopotamian magical slash exorcisitic literature (the already mentioned āšipūtu), it is consistently clear it was understood the name designated a figure closely associated with the underworld. However, it’s hard to disagree with the view that the authors and compilers of the available texts mentioning “Ereschigal” pretty clearly had neither detailed knowledge about her character and position in Mesopotamian theology, nor much interest in it.