The place where I synthesize all the opinions I've formed by stealing the ideas of other bloggers. Because I'm a bad writer. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I’m upset because I want to change the world but the world is too big and people are too mean

448K notes

·

View notes

Photo

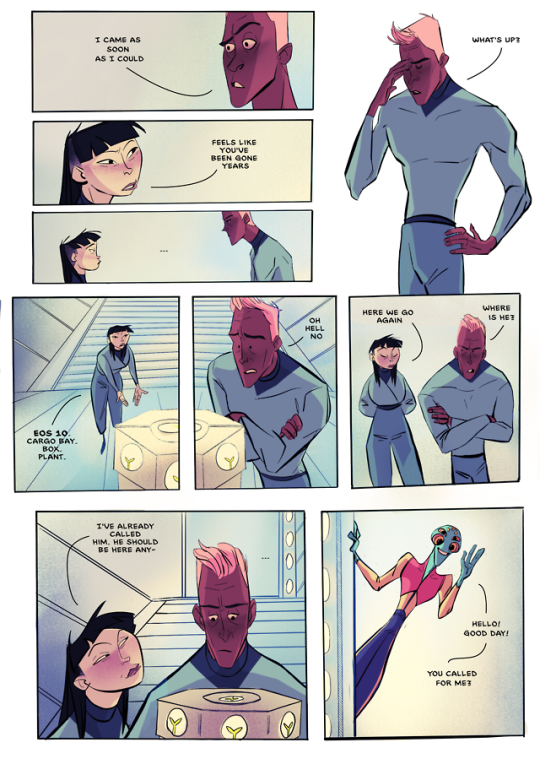

Earlier this year, we asked the amazing @paticmak to illustrate the first scene of @eos10radio‘s season premiere— and here it is! We’re in love with it! And the best part is that we have a scene from episode 302 that we can’t wait to show you, coming soon. :)

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Just finished this other boi!! Critical Fail, Sarah Lindstrom, 2017

17K notes

·

View notes

Audio

573 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are there any tips I can keep in mind while my story goes through quieter moments? I'd like to write smaller character moments to offset the big bombastic moments, but I'm worried that my writings will not seem genuine or engaging to readers.

Thanks for asking!

First off, generally speaking I’d advise to go ahead and write everything. It’s often easier to trim what doesn’t work or slows down the story later than it is to fatten it up. What you write might have seeds that lead to something else later down the road. Anything not written down is forgotten!

I’m reading a couple things in your question, one is about character development (genuine) and the other is about pacing (engaging). Both are really important to a good story (by Western standards) and are often more of an art than a science. There are some tips that will help you, though, so never fear!

As I stated before, pacing is like the heartbeat of your work. When I think about your question in particular, I like to think about story structure and narrative arcs. This is one way to tell a story, and it’s really good for a lot of stories. This involves following a format of Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Denouement. There are some more complex models of this, but this model is good enough for what we’re talking about.

There can be all kinds of good places to slip in quiet moments of character development, and most of these come in the calm between large action scenes. They fit in really well right after the climax of a story, but also after any failures the protagonist suffers in which the supporting characters must help lift the protagonist and encourage them to proceed towards the climax. If we’re going back to the heartbeat metaphor this would be like the instant before the heart actually beats. The most important thing is that you never want the heart to stall out, so you want to keep these moments short and paced just so that they do not interrupt the flow of the story.

Personal character moments do not need to stall your story, and can carry their own weight and intensity as the story drives on. The most important way to make sure that your personal character moments don’t stall your story is to make sure that they are relevant to the plot. This falls back into the answer that I gave to my first question where I explained that there is a reason we don’t frequently write stories that include incidental events like evacuation and rest in explicit detail.

In terms of character development, you want to make sure that you’re treating your characters as though they were real people each with their own story. This means each of your characters should have objectives that they are trying to accomplish, and obstacles that stand in the way of their objectives. Even the laziest of characters is trying to just be lazy, sometimes with great difficulty if their obstacle is the protagonist urging them to participate in the greater action of the story. You should approach this on a scene-by-scene basis, and for your whole story overall.

Not every character’s superobjective (what they want by the end of the story) needs to be resolved within your story. Many side characters may not see their superobjectives resolved, particularly if they were only relevant for one or two scenes. “So how do these little slower character moments relate to a character’s superobjective?” I hear you cry. Never fear! There are a variety of answers and many of them are going to be specific to your story.

Some examples include (but are not limited to):

-The protagonist is often working towards a place of peace, which usually involves having people close to them; establishing bonds of friendship or romance works towards that goal

-A romance or close friendship could be used to sow the seeds of doubt in an otherwise duplicitous or antagonistic character

-Close character moments can establish the weaknesses of a character or serve as exposition for their superobjective

The most important tip to keep in mind is that you want to keep things moving and you want to keep things relevant. You don’t have to keep things moving at the same speed, but also try not to slam on the breaks and then drive in the slow lane for too long. Keep your close personal scenes concise and relevant to your story.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's your advice for writing a relatable character for a wide audience without making them a two dimensional blank slate that anyone can slip their own self onto?

Great question! You want to write characters that have a wide appeal so that you reach as big an audience as possible, and I think that’s a reasonable thing to want. Characters become relatable to the reader through shared experiences and thoughts. This is one of the biggest stretches for a writer because it means that you really have to get out of your own head and empathize with someone else’s viewpoint - even one that maybe diametrically opposed to your own!You weren’t specific about what roles the characters you’re writing about will be fulfilling in your story, so I’ll try to touch on the big three: Protagonist, Antagonist, and Supporting Character. Keep in mind that these roles aren’t rigid boxes but more like adjacent seas. At any time they could exchange currents and mix together in fascinating ways.Something else to keep in mind before you go in is that no character can, or should, appeal to every human on the planet. And to some extent, readers will see in your character what they want to see. That’s okay. Your particular audience will determine much of what makes a character relatable - but there are some timeless themes you can encounter that span generations.Protagonists are often most relatable when they display fragility in some fashion. This gives the supporting characters something to do in terms of support. This fragility needn’t be constant, and can take a myriad of forms relevant to your characters. Fragility can come in the form of doubt, physical weakness, temptation, emotional weakness, or ignorance. As the author you want to try to control the reader’s perception of that fragility to suit your needs. Antagonists are most often relatable when they have clear goals that they ambitiously pursue. They don’t have to be stop-at-nothing criminals, though they might be. I like to use Lex Luthor as a good example of a well-rounded and, in some very dark ways, relatable villain. Lex Luthor wants to build up humanity, and his public aim is to do away with Superman because he is a dangerous alien. From Lex’s perspective, Superman’s alien origin makes him untrustworthy, a nuke with a brain of its own. Similar to Dr. Manhattan but less powerful, certainly. But Lex has money enough to build infrastructure, hospitals, homes. He has undeniably created jobs. Is he a soul-sucking conservative monster? Yeah. But he is motivated not just by greed but by a love of humanity. Just humanity, though. No aliens.Supporting characters are relatable in a variety of ways. Harry Potter is a great example of a stable of relatable side characters. From the muggle born boy who loves football to the wacky conspiracy nut, what make supporting characters relatable is how much they remind us of the people that populate our own world. These are the goofy, adorkable normies that bumble through our lives (as we perceive them) but also our wise but limited teachers, our comfortable but restrictive parents, and our best friends and lovers.One of my favorite things to do when coming up with traits for these people is to consider the traits of people I know and turn them up a little bit. I read that in a book somewhere and it seems to work well for me. Don’t take all the traits from one person, just one or two defining traits, and maybe combine them with some from another person you know. And if you’re an introvert and you don’t get out much, that’s okay! There’s universes full of people you can know or get to know in books, movies, television shows, fanfiction… you get the idea. The people who’s traits you’re borrowing don’t have to come from reality.Language is another way in which authors can make their characters relatable (or more alien!) Consider the difference between the way Starfire and BeastBoy speak in the Teen Titans. Also please consider that anime characters almost never speak English like real English speaking people do. Sorry, weeaboo fans! Those characters are meant to speak in a different language, and even that is exagerated for dramatic effect. Try to avoid imitating that style in your dialogue if you’re looking for wide appeal.Characters with more ostentatious choice of words sound old and formal. Characters that use a lot of slang seem uneducated and brutish. Give your character a vocabulary that makes sense for their own intelligence and education level. That’s not necessarily the same as your own, in fact it probably isn’t!A final note on this: these norms have been established traditionally by white cishet male writers. Because they have set cultural standards and practices for millennia, my advice on relatability is based off of the assumption that you’re writing for this patriarchal society. It’s reasonable to not do that.

0 notes

Note

Often I worry that, in my writing, my descriptions will come off as "clunky" or cumbersome to read- do you have any suggestions for more streamlined prose?

This is a lovely and difficult question. I think what makes it most difficult is that I’m operating without a sample of your particular writing so I’m not sure what about your style might be considered cumbersome to read, and I’m not sure if that means you’re being wordy, your word order is a little wonky, or you’ve got a pacing problem. It could be some combination of these things, or something else entirely, but I’m going to answer in the best way that I can.

The first thing that I’d do is ask what draft of your piece you are on? If you’re still writing your first draft, and you’re just testing the waters to see if the idea is solid, then that’s the kind of feedback you should be looking for. You can always come back and fix problems in later drafts - what you want to do first is get it finished. Remember it’s always easier to pare down than it is to build up!

Assuming you’re revising a complete draft, you want to look at your descriptions and determine their relevance to the story. Some authors can get away with adding quite a bit of detail, and some can get away with adding very little detail. Your level of detail will vary, but finding the right balance can be tricky. You want to include descriptions that conjure up an image in readers’ minds but that don’t slow down the pacing of your work.

Pacing would be like the heartbeat of your piece - it speeds up when there is action and slows down when there is downtime. If it slows down too much, then the reader runs the risk of getting bored and putting your story down for some other activity. That’s why activities such as evacuation and rest are usually cut from stories. You can alter the pace of your stories in a few key ways.

Short sentences are a great way to increase the pace of a scene, especially when there are two characters engaged in snappy back-and-forth dialogue. I feel the best action scenes are ones that make use of short, guttural or impactful sounding language. She thudded to the floor. He withered shuddering blows. They skidded to a halt. Thudded, shuddering, and skidded all kind of have that onomatopoeia which is nice in the imagination.

Conversely, longer sentences can slow down the pace of your work, particularly when they lead into drawn out exposition or non-sequiturs. Using long sentences can be particularly useful in capturing certain stream-of-consciousness moments, or in giving lush descriptions of your setting. This gets complicated in its own right, though, and again largely leans upon personal taste. Essentially, you still want to keep your descriptions concise. Try to describe a scene by just talking about the things in your mental image of what’s happening that would immediately stick out if you were watching it in a movie or reading it in a comic book.

As an exercise, take a scene from a movie, preferably an opening wide shot or even the whole “Concerning Hobbits” sequence at the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring (2001 Wingnut/New Line) and try jotting down notes of the first things you see in each shot. You probably won’t get much of a detailed description and that’s all right. You can probably get enough information to start writing a coherent description with no more information than you need.

The sky over the green rolling hills of the Shire shone a bright blue. A road, winding round Bag End’s garden fence, led straight to the old gate that sported a sign reading “No Admittance - Except on Party Business!” On this day, though, none were on the road, for they were instead in the fields preparing decorations and setting up tents - at the speed with which Hobbits accomplish such tasks - to get ready for Bilbo Baggins’s one hundred and eleventh birthday party.

Tolkein would have, and did, handle this scene very differently. Of course I omitted Gandalf, who was the one who was present in the movie to perceive the sign, but this was more about the exercise of translating what you jotted in your notes into something on the page. I still urge you to try this and see what you come up with. It doesn’t have to be from Fellowship of the Ring!

The reason I bring up this particular work is that Tolkein quite notoriously gets away with having several-page-long non sequitur backstories about this event or that item or that Elf’s long lived lineage and service in the War of the Ring. For that reason, I was never personally able to read The Lord of the Rings. But I’m not so brazen as to suggest that Tolkein was a poor writer for doing it! Some people really dig that level of detail. So remember who you’re writing for.

If you’re being too wordy, then it might be the number of adjectives you’re using, or the number of verbs you’re including in your sentences (if you’re describing an action scene). The verbs are largely a concern of pacing, and shorter more digestible sentences, especially in earlier drafts, will help make the action you are describing much clearer. Take, for example:

1.)

They somersaulted into the room while drawing their katanas, slashing expertly at the three ninjas who were pouncing through the air from above in a triangle death noose and stabbing with their finely sharpened sais. Their attack successful, the ninjas tumbled through the air, blood trailing from where they had cut open the stomachs of two of them while the third one smashed headlong into the wall.

2.)

They somersaulted into the room. Three ninjas armed with sais pounced on them as they entered. They recognized the attack immediately: it was the triangle death noose! They slashed expertly with their twin katanas at the ninjas, wounding two and sending the third tumbling into the wall. Traces of blood spattered onto the ground as they stood up to reposition for the next attack.

The second example is much more concise, flows better, and uses choppier language to set the pace. There’s no extra information in there, but you can get a pretty clear idea of what is going on. It’s okay to let the reader’s imagination run with the concept for a while.

Remember it wasn’t until Harry Potter and the Cursed Child that Hermione was finally portrayed as the woman of color she was supposed to have been the whole time - most audiences imagined her to be white. Some of this could be blamed on JKR’s description of Hermione, but by not pegging Hermione as a woman of color she kept the focus of her character on her intelligence and natural abilities - not these things because or despite the fact that she’s a person of color. Hermione wasn’t meant to make that kind of statement, and so her representation was subtle. To some extent, so was Dumbledore’s homosexuality. The difference being that there weren’t many situations where Hermione’s being a woman of color in magical England would likely have been an issue in the story - or at least that is JKR’s contention.

Another example of someone who was vague on descriptions is H.P. Lovecraft. He is famously bad at giving detailed descriptions, particularly in his early work, where you get babbling about pseudopods and formless shapes and sights that are indescribable (so indescribable that he won’t even try). Later in his work he calmed down and started giving his nameless horrors names, I think in large part thanks to the influence of his wide epistolary network. But Lovecraft is best known for using very ostentatious language. He was inspired by the late 19th century authors, particularly Edgar Allen Poe, and so mimicked that style more into the early 20th century when such ostentation was falling out of vogue with the common reader and you could pick up a weird fiction magazine for a nickel on the street corner.

So there is a lot to be said for style, and the authors that influence you, and how those things come together. An old Pixar trick is to take things about stories you like and didn’t like and determine what it is you liked and didn’t like about them - and if you didn’t like them what would you change to make it a story you did like. You can do the same thing on a smaller scale by looking at a paragraph or a sentence and figuring out whether you like or dislike a sentence and why. That’ll tell you a lot about the way you prefer to write.

Word order is something you should pick up from a style guide. I’m bad at describing it and okay at doing it. A bit dated, but Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style is a good book to read for any/all of this stuff. It’s not even very long, or at least the one I picked up at Half Price Books for $4 isn’t. It’ll be the best book on grammar you ever purchase.

Hope that answers your question! Let me know if I can provide any more follow up information!

1 note

·

View note