Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Wallachia in the 15th Century

Tl;dr: the 15th century Balkans were a messTM. It was like a complicated high school drama where everything revolved around who liked who and you totally did not want to be voivode of Wallachia.

What the hell is a Wallachia?

In the 15th century what we today call Romania was divided into three main principalities: Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania. Wallachia was a relatively young principality. The original principality came into existence in 1310 and was officially recognised by the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church in 1359. [1] Under the rule of Radu’s grandfather, Mircea the Old (1386-1418) the small principality expanded significantly as Mircea worked to unite the smaller pre-existing states under the Wallachian banner. [2] To the north of Wallachia, across the Carpathian mountains, lay Transylvania. Transylvania was a province of Hungary and was ruled by a voivode (prince) appointed by the Hungarian king. Finally, to the north-east lay the third principality of Moldavia which had emerged in 1359. [3]

These Romanian lands lay along the thriving commercial routes linking the east and the west. By the 15th century they played an important international economic role as the guardian of a commercial corridor extending to Asia, via the black sea along which spices and silks from the East would be traded for clothes, velvet and iron from the West.[4]

Whilst this advantageous positioning did bring them wealth it also made them targets for larger empires.[5] External pressures led to internal instability and Wallachian voivodes came and went at an alarming rate - hardly having to time to warm their throne seats before being dethroned by the next pretender. Alliances were everything and yet often meant very little. In sum, being ruler of Wallachia was a bit of a nightmare of a job.

Internal Troubles

One of the major weaknesses of the Wallachian state was that it lacked a well-established principle of succession to the throne. The voivode was elected by an assembly of boyars (noble landowners) and although the throne was usually given to the eldest son of the previous voivode there was no official policy of primogeniture* so any male relative, legitimate or illegitimate, could make a claim for the throne.[6] Consequently, this ambiguous system of succession led to constant struggles between possible heirs for the throne. Each rallying to get the support and votes of various boyar factions creating great internal tension. Additionally, it encouraged external interference in the dynastic struggles. Since, there were so many possible legitimate rulers, foreign powers would often take advantage of this by supporting and pushing their own personal claimant in the hope that when that claimant took the throne they would advance the interests of the foreign power that put them there. [7] This was the case with almost everyone in our story. Vlad II Dracul took the throne with Hungarian support, Vlad III Dracula with the Ottomans and then later the Hungarians, Radu with the Ottomans (multiple times) and Basarab Laiotă with the Moldavians. Though each of these ascensions to the throne involved military takeovers they were each legitimate according to the Wallachian rules of succession.

The instability created by this system is reflected in the length of each voivode’s rule. Between 1418-1476, 11 princes ruled for an average of five years each. Most reigned for multiple terms making the average length of time for a single uninterrupted rule only two years.[8] In fact the longest, uninterrupted rule for this period was only 11 years! And that was under Voivode Radu III.

* a system in which the right of succession belongs only to the eldest child. In the absence of the eldest it proceeds to the next eldest in order of birth and so on.

Relationship with the Ottoman Empire

First contact between Wallachia and the Ottomans occurred in the late 14th century when Mircea the Old agreed to pay tribute to the emerging power whilst retaining Wallachian independence.[9] Commercially, this allegiance benefitted Wallachia by keeping trade routes open whilst also assuring peace and protection from the Ottomans. Consequently, it was maintained by many later voivodes to the benefit of their country.[10]

Relationship with the Kingdom of Hungary

Despite paying tribute to the Ottomans, most voivodes also swore allegiance and loyalty to the other regional power – Hungary. [11] Catholic Hungary controlled the principality of Transylvania as well as the commercially important Saxon cities like Braşov and Sibiu that lay within Transylvania.[12] For Wallachia, maintaining peace with both Hungary and the Ottomans, was a delicate balancing act as the two powers used the Wallachian throne as a battleground for supremacy in the region – electing and dethroning voivodes as suited their agendas. [13]

However, the Wallachian voivodes could also play this game, swearing allegiance to one power to gain the throne and then switching to the other as suited them. [14] Radu and Vlad’s father, Vlad II Dracul, was particularly adept at this. As mentioned before, he originally gained the throne under the support of the Emperor Sigismund, King of Hungary and Emperor of Germany, but later swore allegiance to Sultan Murad II. He took part in campaigns with the Ottomans against the Transylvanians before swinging back and taking part in anti-Ottoman crusades alongside the Hungarians (despite Murad threatening to kill Vlad and Radu whom he was holding hostage for this exact reason). And then eventually, he was murdered by his own boyars who had also switched sides and now wanted someone else on the throne.[15] Relationships truly were fickle for a Wallachian voivode.

Sons as hostages

Radu and Vlad’s childhood stay with the Ottoman’s to ensure their fathers loyalty was not unusual for the period.[16] Previously, Voivode Mihail I of Wallachia had also been forced to send his sons as hostages to the Ottoman court in 1419 after he’d engaged in an anti-Ottoman crusade with the Hungarians.[17] Many other sons of princes or high-ranking boyars were also taken by the Ottoman court to Bursa or Edirne to ensure their fathers would not betray Ottoman interests and to be educated in the Turkish ways. [18] This process was designed to not only ensure the loyalty of their fathers to the empire but also to indoctrinate the sons into being loyal rulers when they succeeded their fathers.

-

Fifteenth century Balkan politics were messy and brutal. Death by old age was a luxury few voivodes could afford, and alliances meant everything. For Radu, this would be no different.

Bibliography

[1] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 30.

[2] Cazacu, Dracula, 3.; Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 20, 30.

[3] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 28.

[4] Cazacu, Dracula, 11

[5] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 27.

[6] Cazacu, Dracula, 15.; Martin Rady, “Historical Introduction,” in Government and Law in Medieval Moldavia, Transylvania and Wallachia, ed. Martin Rady and Alexandru Simon. (Great Britain: University College London, 2013), 8.

[7] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 30.; Rady, “Historical Introduction,” 8.

[8] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 32.

[9] Ibid, 35.

[10] Cazacu, Dracula, 9.

[11] Ibid, 8.

[12] Ibid, 13.

[13] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 38.; Rady, “Historical Introduction,” 8.

[14] Nicolle, Cross & Crescent in the Balkans, 154.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Trow, Vlad the Impaler, 138.

[17] Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, 37.

[18] Cazacu, Dracula, 13.

#radu cel frumos#vlad the impaler#and i darken#radu the handsome#ottoman history#ottoman empire#romanian history#histro#vlad tepes#radu bey#wallachian history#vlad dracula#dracula#context

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radu’s Story

Note: This is the “Hollywood” version of the story including many popular myths about Radu cel Frumos. How true some of these myths are will be further explored in later posts on this blog.

Do you want to hear a story?

It’s about Dracula.

No, not that Dracula, the real one.

No, not Vlad “the Impaler” Dracula. The other one. Radu “the Beautiful” Dracula.

There’s two Draculas! you say.

Well, actually there were three, (not including all the illegitimate Draculas) but I’m here to tell you about the youngest; Radu III cel Frumos.

A quick google search will tell you lots about this obscure Romanian noble – he was the Sultan’s “homosexual obsession”, “the man who killed Dracula”, the man who actually inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a Muslim, a Christian, a weak-pushover and a strong military leader. In fact it will tell you so many things that you may ended up knowing nothing about him. In any case, let me try to give you an overview of the Hollywood highlights of the other Dracula’s life.

The 15th century Balkans

Radu was born sometime between 1437-1439, the third legitimate son of Vlad II Dracul. His father was Voivode (Prince) of Wallachia – barely. Despite being declared Voivode of Wallachia in 1431 Vlad Dracul hadn’t actually obtained the throne until 1436 because 15th century Balkan politics were a messTM.

Now, Vlad Dracul hadn’t been born with the name Dracul but had taken it after being indicted into the Order of the Dragon (Dracul=Dragon in Romanian). The Order of the Dragon was a Holy order of nobles founded to fight the enemies of Christendom - particularly the Ottoman Empire - and by taking the name Dracul Vlad proudly proclaimed himself as a member of this order. His sons, Radu and his two older brothers Vlad (later to be remembered as Vlad the Impaler) and Mircea, were consequently called Dracula meaning ‘Son of the Dragon’.

So, Radu’s early years were spent as a young Christian prince of a rather volatile country. However, Radu did not spend long in his Romanian homeland as by 1444 he, and his older brother Vlad, had been sent to the Ottoman court of Sultan Murad II as hostages.

The ruins of the Fortress of Eğrigöz in north-western Anatolia where Radu and Vlad spent their first few years as hostages before being relocated to the Ottoman capital at Edirne.

As hostages, the brothers were meant to ensure the loyalty of their father to the Ottoman Sultan and stop him from teaming up with Hungary in anti-Ottoman crusades under the threat that Sultan Murad would execute the boys. However, this did not stop Dracul from quickly betraying the Ottomans and assuming his sons dead (after all he still had his eldest son, Mircea, so Vlad and Radu weren’t that important).[1]

But luckily for Vlad and Radu, Murad had other reasons for keeping the boys alive. Through education and indoctrination he planned to raise the boys as good, loyal - and legitimate - future rulers of Wallachia.[2]

As a result the boys were well treated and educated by the finest tutors available, in logic, the Qu’ran, languages, horse riding, battle – all the necessary skills for great future rulers.

How Radu experienced these years in the Ottoman court is unclear. The general consensus is that whilst Vlad was just straight up not having a good time (often being whipped or beaten for being a bad student), Radu was more adaptive - but the consensus stops there. Depending on who you ask you might be told that he “was a compromiser, consumed by the pleasures of the palace” [3], a victim of Stockholm syndrome and “a weakling and a voluptuary, famous for his beauty” [4]. But others will say that he was an intelligent young man with both military and political promise.

However, a key part of his story that is often repeated, is that he was very good looking hence his nickname “cel Frumos” meaning “the beautiful” in Romanian. He attracted many admirers both male and female. Among them was Murad’s son, the future Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror. Although they had a rough start (their first kiss involved Radu stabbing Mehmed and then hiding up a tree) the two became very close and thanks to this relationship Radu gained much power at the court.[5]

Meanwhile, his relationship with his brother deteriorated and the two developed an intense hatred.[6]

At the end of 1447 the news reached the brothers that their father, Dracul, had been killed and their older brother, Mircea, had been buried alive by the Hungarians.[7] It was now time for Vlad, as the eldest, to take the Wallachian throne under the support of the Ottoman Sultan.

As Vlad left the palace of Edirne for Wallachia it would be more than a decade before he saw his younger brother again. And then it would be on the battlefield…

During this time Murad died and Mehmed took the Ottoman throne in 1451. Radu became a prominent figure in the Ottoman court, converted to Islam and played an important role in Mehmed’s conquest of Constantinople (maybe).[8]

However, his life at the Ottoman court ended in 1461 when Vlad (now Voivode of Wallachia) began actively rebelling against the Ottomans. Mehmed, who was busy trying to become the next Alexander the Great, did not have time for this. What he did have, was a perfect replacement for Vlad in the loyal Radu.

So, in Summer 1462 Radu and Mehmed crossed the Danube with 35,000 Ottoman soldiers against Vlad’s meagre 7-8,000.[9] Despite Vlad’s vicious scorched earth tactics and daring night attacks he stood no chance against the superior Ottoman forces and was forced to flee north. When Radu and Mehmed reached the Wallachian capital of Tărgovişte Vlad was long gone but had left a grisly gift that would earn him his nickname Ţepeş – the Impaler. Along the road to Tărgovişte he had planted a forest of impaled Ottoman soldiers that stretched for kilometres…[10]

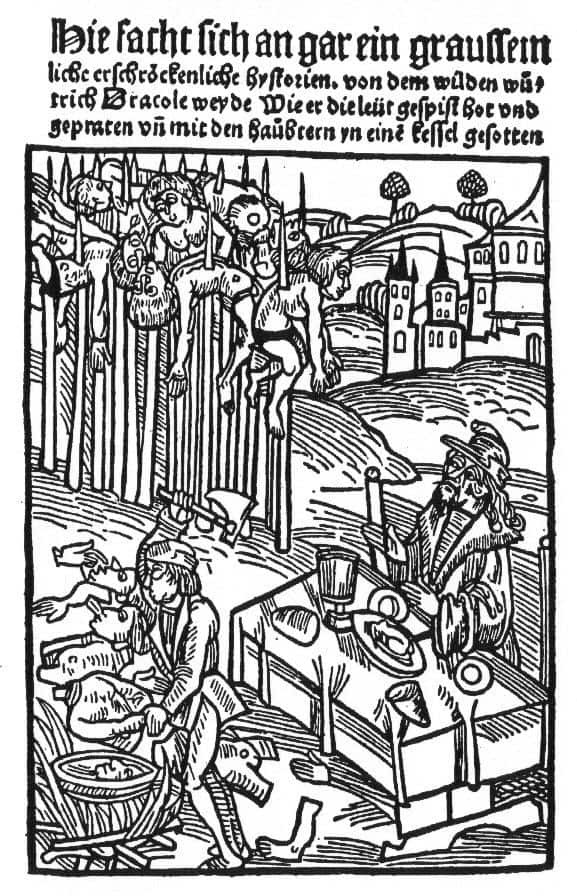

A Saxon woodcut (c.1499) of Vlad enjoying a meal with some new garden ornaments. Despite the fact he definitely did impale people it’s worth remembering that a lot of the Saxon publications about him were essentially propaganda so take the image with a grain of salt.

Despite this horror, Radu took his place on the throne as Voivode Radu III. He ruled Wallachia for eleven years and by 15th century Balkans standards it was almost peaceful. Although he was supported by the Ottomans he managed to win the respect of the local Wallachian boyars (nobles) and maintain peace with Hungary (the other big regional power). However, his real trouble was with the third Romanian state – Moldavia - where Stephen the Great had come to the throne and was wanting to assert his dominance over the region. Stephen did not like Radu, mostly because of his pro-Turkish stance. In 1465 Stephen took control of the previously Wallachian port city of Chilia. There was a period of relative peace but then from 1470 onwards Radu and Stephen became engaged in a serious of border wars that ended with Stephen defeating Radu on November 18-20th 1473. Stephen marched into the Wallachia capital ready to place his own guy, Basarab Laoită, on the throne and Radu, like his brother before him (minus the forest of impaled people), was forced to flee the city leaving all his treasure, effects, clothing, wife and daughter behind.

Three weeks later Radu returned with Ottoman reinforcements and retook his throne (also his wife and daughter). Over the next year the throne continued to alternate between Basarab backed by Stepehn and Radu backed by the Ottomans until January 1475 when Radu was dethroned for the final time, presumably dying sometime soon after.[11]

The details are unknown but there are three main theories as to what caused his death and sudden absence from the historical record:

a) He was executed by Stephen the Great who was sick of having to dethrone him.[12]

b) He died of syphilis, “unloved and unmourned”[13]

c) He became a vampire[14]

My bets are on c)

-

The story of Radu is a good one. However, it’s also built on a lot of assumptions and blatant falsities that have been spread by academic and popular writers alike. Finding “The Truth” of Radu’s life necessitates a return to primary sources. But, how much of person can we really construct from a smattering of 15th century writings? And how much will we never know?

For answers to these questions and more keep an eye on this page...

References

[1] Davin Nicolle, Cross & Crescent in the Balkans: The Ottoman Conquest of Southeastern Europe. (Great Britain: Pen & Sword Military, 2010), 153.

[2] M. J. Trow, Vlad the Impaler: In Search of the Real Dracula. (United Kingdom: Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2003), 140.

[3] Romano, Will. ‘Vlad Dracula’s War on the Turks’. Military History; Herndon, October 2003.

[4] Franz Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978), 207.

[5] Ibid.; Will Romano, “Vlad Dracula’s War on the Turks,” Military History, October 2003.; James Waterson, Dracula’s Wars: Vlad the Impaler and His Rivals. (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2016) 111.; Radu R. Florescu and Raymond T. McNally. Dracula: Prince of Many Faces. (Boston, United States: Little, Brown and Company, 1989), 56.; Masson, Gemma Masson, “Dracula and the Ottomans,” Womenareboring, 15 March 2018. https://womenareboring.wordpress.com/2018/03/15/4286/.; Shibli Zaman, “How the Muslims killed Dracula.” Worldbulletin, 31 July 2013, https://www.worldbulletin.net/historical-events/how-the-muslims-killed-dracula-h114250.html.

[6] Dion Overtoun, “Radu Cel Frumos: The Queer Brother Nobody Cares Dracula Had,” Frightful/Filthy: The Writing of Dion Overtoun, 28 June 2017, https://dionovertoun.com/2017/06/28/radu-the-queer-brother-nobody-cares-dracula-had/.; Zaman, “How the Muslims killed Dracula.”; Florescu and McNally, Dracula: Prince of Many Faces, 59.

[7] Waterson, Dracula’s Wars, 111.; Florescu and McNally, Dracula: Prince of Many Faces, 56. ; Zaman, “How the Muslims killed Dracula.”; “Radu Cel Frumos,” Project Gutenberg, Acessed 30 September 2019, http://www.self.gutenberg.org/articles/Radu_cel_Frumos.

[8] Matei Cazacu, Dracula. (Boston: Brill, 2011), 51.

[9] Kent, Jasper. The Last Rite: (The Danilov Quintet 5). Random House, 2014.; Zaman, “How the Muslims killed Dracula.”; Masson, “Dracula and the Ottomans.”; Trow, Vlad the Impaler, 139.; “Radu Cel Frumos,” Wikipedia, Accessed 8 October 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Radu_cel_Frumos&oldid=920222947. ; Philippe Lemaire, “Recherches sur le vampire,” Site de Philippe Lemaire, auteur de fantastique, Accessed 30 September 2019, https://sites.google.com/site/philip63lemaire/recherches-sur-le-vampire.; “Radu Cel Frumos.” ; Elest Ali, “Is “Dracula Untold” An Islamophobic Movie?” The New Republic, 25 October 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/119991/dracula-untold-islamophobic.; Beyaz Arif Akbas, “Kim Bu Güzel Radu?” Milliyet Blog, Accessed 9 October 2019, http://blog.milliyet.com.tr/kim-bu-guzel-radu-/Blog/?BlogNo=402166.

[10] For a detailed explanation of the numbers involved in this campaign see - Adrian Gheorghe, “Understanding the Ottoman Campaign in Wallachia in the Summer of 1462. Numbers, Limits, Manoeuvres and Meanings,” in Vlad Der Pfähler – Dracula Tyrann Oder Volkstribun?, ed. Thomas Bohn (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2017), 11.

[11] Ibid, 30.;

[12] Franz Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978), 339.; Tasin Gemil, Romanians and Ottomans in the XIVth to the XVIth Centuries, (Bucharest: Editura Enciclopedicã, 2009), 203.; Jonathan Eagles, “The Reign, Culture and Legacy of Ştefan Cel Mare, Voivode of Moldova: A Case Study of Ethnosymbolism in the Romanian Societies,” (University College London, 2011), 13.; Liviu Pilat and Ovidiu Cristea, The Ottoman Threat and Crusading on the Eastern Border of Christendom During the 15th Century. (Boston, United States: Brill, 2017), 143 – 145.

[13] Kurt W. Treptow, Vlad III Dracula The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula, (Oxford: The Center for Romanian Studies, 2000), 159.

[14] Trow, Vlad the Impaler, 208.; Waterson Dracula’s Wars, 184.

[15] Lemaire, “Recherches sur le Vampire.”

#radu cel frumos#radu bey#hollywood story#vlad tepes#vlad the impaler#radu the handsome#wallachia#ottoman history#history#radu güzel#dracula#radu dracula#radudracula#vlad dracula tepes#vlad dracula#romanian history#romania#wallachian history#and i darken#the conqueror's saga#ottoman empire

29 notes

·

View notes