Text

When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress

By Gabor Maté

Published in 2004

Maté analyses medical research and draws on his own clinical experience as a physician to explore the connections between psychological stress and pathophysiology. He rejects the dualism that pervades Western medicine (i.e. body and mind are two distinct entities), instead approaching health and illness from a holistic perspective wherein mind and body are interconnected. The book shares many similarities with The Body Keeps the Score (though I did find TBKTS more informative and engaging than Maté’s book). I am also a little suspect of the veracity of some of the claims made in the book, but it was interesting all the same. I found the evidence and analysis in TBKTS more compelling.

Below are a collection of excerpts that I found especially informative and/or intriguing:

“The experience of stress has three components. The first is the event, physical or emotional, that the organism interprets as threatening. This is the stress stimulus, also called the stressor. The second element is the processing system that experiences and interprets the meaning of the stressor. In the case of human beings, this processing system is the nervous system, in particular the brain. The final constituent is the stress response, which consists of the various physiological and behavioural adjustments made as a reaction to a perceived threat. Equally important is the personality and current psychological state of the individual on whom the stressor is acting... [e.g.] loss of employment will be perceived as a major threat [by some], while the other may see it as an opportunity. There is no uniform and universal relationship between a stressor and the stress response. Each stress event is singular and is experienced in the present, but it also has its resonance from the past... what defines stress for each of us is a matter of personal disposition and, even more, of personal history.”

“[Hans] Selye discovered that the biology of stress predominantly affected three types of tissues or organs in the body: in the hormonal system, visible changes occurred in the adrenal glands; in the immune system, stress affected the spleen, the thymus and the lymph glands; and the intestinal lining of the digestive system. Rats autopsied after stress had enlarged adrenals, shrunken lymph organs and ulcerated intestines... Selye’s triad of adrenal enlargement, lymphoid tissue shrinkage and intestinal ulcerations are due, then, to the enhancing effect of ACTH on the adrenal, the inhibiting effect of cortisol on the immune system and the ulcerating effect of cortisol on the intestines.”

“We need to mount a stress response in order to preserve internal stability. The stress response is non-specific. It may be triggered in reaction to any attack - physical, biological, chemical or psychological - or in response to any perception of attack or threat, conscious or unconscious. The essence of threat is a destabilization of the body’s homeostasis... thus, the stress response may be understood not only as the body’s reaction to threat but also as its attempt to maintain homeostasis in the face of threat”

“Three factors that universally lead to stress: uncertainty, the lack of information, and the loss of control.”

“Parenting, in short, is a dance of the generations. Whatever affected one generation but has not been fully resolved will be passed on to the next... Blame becomes a meaningless concept if one understands how family history stretches back through the generations. “Recognition of this quickly dispels any disposition to see the parent as villain” wrote John Bowlby.”

“A therapist once said to me, “If you face the choice between feeling guilt and resentment, choose the guilt every time.” … If a refusal saddles you with guilt, while consent leaves resentment in its wake, opt for the guilt. Resentment is soul suicide.”

“Compassionate curiosity about the self does not mean liking everything we find out about ourselves, only that we look at ourselves with the same non-judgmental acceptance we would wish to accord anyone else who suffered and who needed help.”

“If there is one lesson... it is that people suffer when their boundaries are blurred... disease itself is a boundary question. When we look at the research that predicts who is likely to become ill, we find that the people at greater risk are those who experienced the most severe boundary invasions before they were able to construct an autonomous sense of self [see the results of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study pub 1998].”

0 notes

Text

Chasing the Scream: The Search for the Truth about Addiction

By Johann Hari

Johann Hari has witnessed the pain and destruction wrought by drugs - his family members and his ex-boyfriend experienced addiction. It was primarily these circumstances that motivated him to learn more about the so-called “war” on drugs - this book is a product of that process. Hari writes about how the war on drugs began and how it has evolved over the decades. He includes the conversations he has with researchers, politicians, families, health professionals and police (https://chasingthescream.com/ includes a comprehensive listing of the interviewees and various recordings) - he talks with individuals who have had substance use problems in the past, individuals who continue to use, those whose loved ones have died as a direct result of substance use, and those whose loved ones have died as an indirect result of the war on drugs itself. For the book, Hari travelled to many places including Portugal, Mexico, the US, the UK, Vietnam, Switzerland, Sweden and Uruguay. He explores the various policies and histories of these countries.

The book has received considerable attention, it has been praised but also criticized. It was not difficult to find criticisms online from esteemed people challenging Hari’s approach, data, citations, and various historical examples. For example, one of Hari’s aims in this book, is challenging the pharmaceutical theory of addiction (i.e. drugs are “so chemically powerful they hijack your brain”). Hari cites the Rat Park experiment and relies on it heavily to argue this point. But his perspective, analysis and interpretation of this experiment is oversimplified - the experiment itself is flawed, has not been able to be replicated, and has been widely criticised. Hari argues that the experiment shows environment is the key (if not only) factor in addiction, but he overstates its influence and disregards the significance of biological contributors in addiction. Either way, his writing has definitely added to and encouraged discussion about: whether drug use should be dealt with as a health issue or a criminal/legal issue, how and why people use drugs, and how and why different people, governments and countries have implemented different ways to change drug use in society. He writes extensively about the trauma and disconnection faced by individuals struggling with substance use - how the repression and punishment of addicts arguably pushes them deeper into their addictive behaviours as they become further ostracised and disengaged.

Hari is both thorough and moving in his writing about how and why shame and stigma become further entrenched when addiction is made a crime, and how the cycle of trauma, drug use and punishment becomes endless without adequate and effective treatment and prevention. He juxtaposes the US (as an example of how policing and punishment dominate over treatment/prevention) with Portugual to illustrate how differing approaches to drug use affect stigma and a person’s ability/willingness to seek help and support for addiction. Punishing someone, shaming them, caging them and making them unemployable “traps them in addiction” whereas with the correct treatment team in a safe, trusting environment, that person can instead “do something [they] have been running away from for years - express [their] emotions, and tell [their] story truthfully.” While in parts confronting, what I found most interesting to read about was the social, emotional and cultural underpinnings of drug use - how drugs may be used in desperation, after trauma, or for pain to “fill the emptiness that threatens to destroy” someone. Below are some of the quotes from the book that I found most though-provoking:

“A kid who is neglected or beaten or raped finds it hard to trust people and to form healthy bonds with them, so they often become isolated... Professor Peter Cohen writes that we should stop using the word “addiction” altogether and shift to a new word: “bonding”. Human beings need to bond. It is one of our most primal urges. So if we can’t bond with other people, we will find a behaviour to bond with, whether it’s watching pornography or smoking crack or gambling. If the only bond you can find that gives you relief or meaning is with splayed women on a computer screen or bags of crystal or a roulette wheel, you will return to that bond obsessively. One recovering heroin and crack addict on the Downtown Eastside, Dean Wilson, put it to me simply: “Addiction,” he said, “is a disease of loneliness.”

“Could it be that these hard-core addicts were all terribly damaged before they found their drugs? What if the discovery of drugs wasn’t the earthquake in their life, but only one of the aftershocks?”

“If your problem is being chronically starved of social bonds, then part of the solution is to bond with the heroin itself and the relief it gives you. But a bigger part is to bond with the subculture that comes with taking heroin - the tribe of fellow users all embarked on the same mission and facing the same threats and risking death every day with you. It gives you an identity. It gives you a life of highs and lows, instead of relentless monotony. The world stops being indifferent to you, and starts being hostile - which is at least proof that you exist, that you aren’t dead already... the heroin helps users deal with the pain of being unable to form normal bonds with other humans. The heroin subculture gives them bonds with other human beings.”

“The wonder of nicotine patches, then, is that they can meet a smoker’s physical need - the real in-your-gut craving - while bypassing some of the really dangerous effects of smoking tobacco. So if the idea of addiction we all have in our heads is right, nicotine patches will have a very high success rate. Your body is hooked on the chemical; it gets the chemical from the nicotine patch; therefore, you won’t need to smoke anymore. The pharmacology of nicotine patches works just fine - you really are giving smokers the drug they are addicted to. The level of nicotine in your bloodstream doesn’t drop if you use them, so that chemical craving is gone. There is just one problem: even with a nicotine patch, you still want to smoke. The Office of the Surgeon General has found that just 17.7% of nicotine patch wearers were able to stop smoking. How can this be? There’s only one explanation: something is going on that is more significant than the chemicals in the drug itself. If solving the craving for the chemical ends 17.7% of the addictions in smokers, the other 82.3% has to be explained some other way... that the chemicals themselves are the main cause of drug addiction - that assertion doesn’t match the evidence... with the most powerful and deadly drug in our culture, the actual chemicals account for only 17.7% of the compulsion to use [difficult to quantify this directly, but won’t unload about that here...]... a [key] distinction... physical dependence occurs when your body has become hooked on a chemical, and you will experience some withdrawal symptoms if you stop... but addiction is different. Addiction is the psychological state of feeling you need the drug to give you the sensation of feeling calmer, or manic, or numbed, or whatever it does for you... you can nurse addicts through their withdrawal pains for weeks and see the chemical hooks slowly pass, only for them to relapse months or years later, even though any chemical craving in the body has long since gone. They are no longer physically dependent - but they are addicted. As a culture, for one hundred years, we have convinced ourselves that a real but fairly small aspect of addiction - physical dependence - is the whole show. “It’s really like,” Gabor told me one night, “we’re still operating out of Newtonian physics in an age of quantum physics. Newtonian physics is very valuable, of course. It deals with a lot of things - but it doesn’t deal with the heart of things.”

“The answer doesn’t lie in access. It lies in agony. Outbreaks of drug addiction have always taken place, he proved, when there was a sudden rise in isolation and distress - from the gin-soaked slums of London [1700s] to the terrified troops in Vietnam... deep driver of the prescription drug crisis [in the US]?... The American middle class had been painfully crumbling even before the Great Crash produced the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. Ordinary Americans are finding themselves flooded with stress and fear. That, Bruce’s [Professor Bruce Alexander] theory suggests, is why they are leaning more and more heavily on Oxycontin and Vicodin to numb their pain.”

Substance abuse is “only a symptom of some suffering, and we have to reach the reasons that make addicts want to be out of their heads much of the time... You can stop using drugs for a while, but if you don’t solve the problems you have in your mind, things will come back. We have to work [on] the trauma in your life, and only then can you change the way you deal with it.”

0 notes

Text

The Good Immigrant USA: 26 Writers Reflect on America

Edited by Nikesh Shukla & Chimene Suleyman.

This book is one of the best I have read this year. It is a collection of essays by first- and second-generation immigrants, detailing their varied experiences of living in an increasingly divided America. The essays explore race, identity, loneliness, grief, community, prejudice, discrimination, belonging and family. While the writers share some similarities, the differences in their styles, perspectives and experiences are many. Each has a distinctive voice. They reflect on their upbringing and their relationships, they discuss race relations and their personal experiences of discrimination and rejection and isolation. They describe the humiliation, judgment, despondence and shame they feel as they struggle to find where and how they fit, navigating different (and sometimes conflicting) attitudes, cultures and beliefs. The experiences of those who grew up in America as the child of an immigrant contrast with those who have grown up overseas and subsequently moved to America as an adult. They are stories of hope, trauma, loss and heartbreak. Despite this, there is a definite, albeit subtle, undercurrent of humour as a mechanism of staying afloat when things are bleak. This is something that I particularly enjoyed in this book.

The essays portray explicit examples of racism/discrimination - for example, the physical bullying of a writer’s young brother due to his race and ethnicity. They also reveal examples where the racism/discrimination is insidious - just as damaging - but more hidden, examples that many white people are oblivious to, that really made me think. While racial groups and their individual experiences are extremely diverse, there are aspects of life that white people generally just don’t have to consider or deal with in the way that many non-whites do. Even, for example, just the ideas of race and ethnicity themselves - white people don’t really notice their race and ethnicity, they quite simply don’t have to worry about it. They don’t have to worry about it affecting their being chosen last for a job or for housing. They don’t have to worry about arousing suspicion (due to their race or ethnicity) entering buildings or spending money or going through an airport. White people are never held personally responsible for the actions of other people because of race or ethnicity. Even just the idea of being treated as an individual, not lumped together into a homogenous group that others may ascribe grossly inaccurate characteristics to - one cannot underestimate the damaging effect of stereotypes on minorities. The way a whole country and/or culture is labelled and reduced down to fit into a single category erases the rich diversity that exists within these groups. Not to mention that each group and all the individuals within different races/ethnicities all have very different experiences of racism and racial inequality.

A common thread is the challenge of finding where one belongs and questioning if one belongs at all, especially when it feels like nowhere is home. Some write of feeling “anchorless”, having a profound sense of disconnection wherever they go, a constant feeling of being the outsider that spirals into a burdensome loneliness. Some describe feeling despondent, others detail the shame that compounds this loss, as they struggle with the expectations of themselves and others, feeling they should be grateful for living in ~the greatest country in the world~ and having the opportunity (debatable) to pursue the American Dream (whatever that is). Chigozie Obioma alludes to this in his essay The Naked Man (the title of which comes from the ancient proverb “beware of the naked man who offers you clothes”) where he describes his initial naivety that evolves into disappointment:

“It occurred to me, then, that America was not the man in shiny garments as I had often believed... it must have been this realization that had moved my friend so forcefully and driven him out of the country. Perhaps he’d come to see that America was a naked man who hid himself behind the cloak he holds up for others to take. And I, like many others, have now started to see his nakedness, exposed in the bright light of the living day.”

Yann Demange’s personal account about his upbringing is titled “Long Answer” with answer referring to his response to the incessant questioning of “Where are you from? (No, where are you from originally though?...)”

“I hadn’t known where else to look. There were no North African kids at my inner-London comprehensive school. The playground seemed divided into whites and blacks. So I ended up with the West Indian kids, along with a few of the South Asian kids. They were the ones who would have us. We were “in” but also the “outsiders”. The confusion even extended to my name. My first name is actually Mounir, but my brother convinced my mother to change it... he had experienced so much racism as a young black man in France... he told my mother I would have the same fate as an Algerian... The way he saw it, I was “white passing”, so why flag up my ethnicity with my name?”

Demange describes the alienating feeling of being simultaneously estranged from but also part of the “disenfranchised postcolonial North Africa diaspora tribe”. Many of the writers describe a similar feeling of displacement.

The election of Trump in 2016 is referred to throughout as something that many felt accentuated the division, racism and bigotry that existed (and continues to exist) in America. His election was seen to legitimize the stigmatization of the ‘other’ - many clearly felt a visceral fear in the immediate days and weeks following his win. In her essay ‘Skittles’ (a reference to Donald Trump Jr’s comparison of Syrian refugees to a bowl of skittles...), Fatima Mirza writes about how being stigmatized as the ‘other’ makes moving states much more difficult (especially when that state is Texas where many have Trump signs in their backyard). When her brother moves to Texas with their Muslim family, Fatima remains in a different state. Her younger brother remains in close contact though - they talk often as he struggles to feel safe in his new school and city. He describes to her feeling unable to talk to his mother and father as he does not want to upset them or make them feel that they shouldn’t have moved. He turns to his sister for advice on how to fight back to bullies and what to say. They joke about it, but both are clearly hurt by what is unfolding. He makes Fatima promise not to say anything to their parents (despite her insistence that they should know). I cannot imagine how lonely and distressing that must feel, to keep hidden from your own parents that you are being taunted and physically bullied and preyed upon.

Jim St Germain’s essay “Shithole Nation” was probably one of my favourites though. I read it twice because I so enjoyed his honesty, intensity and dark humour. He describes candidly how his life has changed - from ending up in a group home (after getting involves with drugs, weapons, fights and many near misses with fatalities) to co-founding the Preparing Leaders of Tomorrow (PLOT, a nonprofit that provides mentoring to at-risk youth). He shares the axiom that drives his work: “those closest to the problems are closest to the solution”.

I will definitely re-read this book in future. Also, if you are wondering about the tongue-in-cheek title, the editors explain it as “a response to the narrative that immigrants are ‘bad’ by default until they prove themselves otherwise. They are job stealers, benefit scroungers, girlfriend thieves, and criminals. Only when they win an Olympic medal, treat you at your local hospital, or rescue a child from the side of the building do they become good.”

0 notes

Text

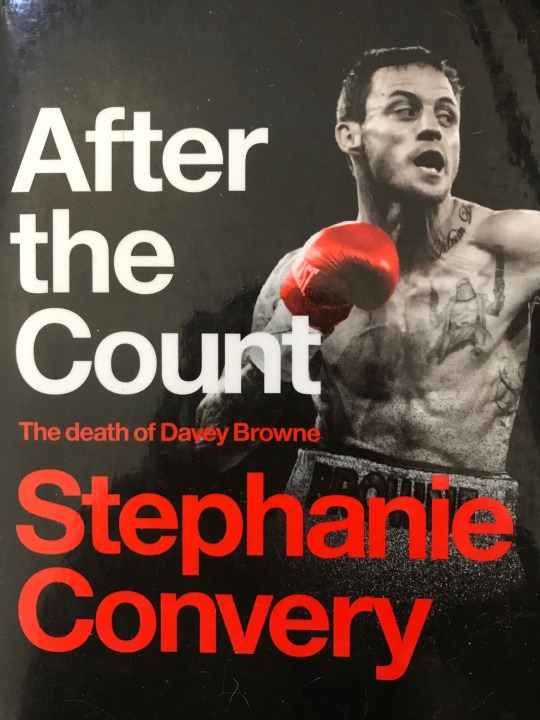

After the Count: The Death of Davey Browne (by Stephanie Convery)

(Warning: this is a LONG post... I have condensed it multiple times but there are just so many sections and themes and quotes to explore it is difficult to cut it down further)

Stephanie Convery fell into the sport of boxing almost by accident. But once she started, she quickly came to love it. It is both therapeutic and challenging, giving her a visceral sense of agency and mastery that she struggles to find elsewhere. It fulfills her desire to push the boundaries of “physical possibility”. However, her enjoyment and the satisfaction she feels when she fights is tempered by her knowledge of the dangers involved. Her unease grows when she learns of the death of Davey Browne. Her personal experience with the sport, and the deep empathy she has for Browne’s family, drive her to investigate and write about Browne’s life and death within a wider discussion of the history and culture of boxing itself.

She is thoughtful in how she approaches his family and is understanding when several people in his life decline (for various reasons) her invitations to talk. In writing the stories and insights of those who do talk, she is sensitive and articulate. Her book is testament to her determination not to let Browne’s story “fall away into the shadows and be forgotten”.

Convery covers a lot of ground. This includes but is not limited to:

the role of money and regulation in sport

the accountability of sporting codes and the people involved in keeping athletes safe

the influence of class in sport

violence and aggression (both in sport and in wider society)

gender in sport

concussion, head injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in sport

the research behind CTE and its prevention and management in sport

Convery explains how the risks and insidious effects of head trauma are compounded by a lack of awareness among athletes about the danger of concussions. Many are unaware of the signs and symptoms and that their onset is not always immediate. This lack of awareness necessitates a much more open discussion about head trauma, she argues, whereby athletes should be made aware from a young age about the risks and signs of head trauma. She cites the 2013 example of Rowan Stringer, a female rugby player who died aged 17 after suffering two concussions within a week. A coronial inquest found she had texted friends about symptoms (incl. headache, tinnitus and fatigue) that she was experiencing after being “kicked in the head” during rugby games on May 3 and May 6. She was never diagnosed after these games, but her text messages expressed that she had “googled concussion”. Many have argued that had she understood the seriousness of head trauma, she may have been better able to make an informed decision about whether to get back on the field to play in the final game on May 8, where she suffered the injury from which she never regained consciousness (it is widely reported that Rowan suffered SIS (second impact syndrome) - the existence of this condition is disputed by some, but there is a lot of information online and it is not something that I’m going to delve into here because I really don’t understand it enough and this post is already going to be too long).

Convery argues there is a more sinister problem, however, that is more difficult to change: the win-at-all-cost attitudes (e.g. where athletes who play through injury/concussion are often viewed as “heroic”...) that pervade sport. These entrenched attitudes were a factor in both Rowan and Browne’s stories. Rowan felt an obligation to keep playing while injured. Convery believes that, in boxing, attitudes about “winning at any cost” are intensified by a “conception of masculinity that pride[s] endurance through all kinds of pain”. This idea (that masculinity underpins some of the more dangerous attitudes and behaviours in sport, especially boxing) is explored throughout the book:

Convery describes the restraints that “masculine pride put on a person who [finds] themselves out of their depth in a fight. To be seen to bow out because you had concerns for your safety would be tantamount to saying you were not tough enough, not good enough, not man enough to continue. And for a sport that [runs] on the volatile fuel of masculinity, [is] unacceptable. So the fighter would put on a show of protesting the referee’s decision… whether the rules didn’t allow him the option of saving face, or sheer masculine pride prevented him from bowing out of his own accord, Davey Browne stood up for just one more round and it killed him”

Convery discusses her own various encounters with trainers and fellow boxers, some of whom welcome her, others who have an obvious unease about female boxers and a “disdain for traditionally ‘feminine’ traits – submissiveness, for example, and physical weakness, but also gentleness, meekness, care”.

Evidence gathered from interviews and extensive research is used throughout her writing. She shows, for example, how the unwillingness of sporting codes, in Australia and internationally, to recognise the risk of concussion and CTE in contact sport (let alone participate in critical research on head injury) further inflames the issue of head trauma in sport. She refers to (among others) the NFL in America, which is notorious for denying and covering up the risks of repeated head trauma. Former players have sought compensation from the NFL for concealing the risks of CTE (and the poor mental health, seizures and memory loss that comes with it) and have put sustained pressure on the organisation to implement more safeguards into the sport. The AFL has problems of its own (see https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/26/sports/afl-football-concussions.html).

While she has an obvious bias, Convery is rightly critical of the way other sports (that usually attract more money and sponsorships by virtue of their popularity) are viewed in stark contrast to boxing:

“Clinically... there is very little difference between one torn hamstring and another, or between two dislocated shoulders… research [of Dr Ann McKee et al.] showed that while the sporting contexts in which CTE developed might be different, the cases were alike in their basic physiology. So what, then, differentiates the sports? Why is boxing considered barbaric, while football continues to march ahead? Many would argue that it’s a matter of intention. That collisions in football or gridiron or even rugby league are not intended to hurt the other person or render them incapacitated, whereas in boxing this is the primary objective; strikes to the face are the point of the sport… the distinction [is] somewhat a matter of degrees. Violence in football wasn’t non-existent – all the crashing and tackling and throwing and shoving was hardly physically benign – but it was sublimated, somehow. Boxing made explicit what in other sports sat just below the surface. The questions that it therefore raised about human behaviour – the undeniable confrontation with mortality that came from making that violence explicit and turning it into a ritual of sorts – was what made people uncomfortable.”

This evolves into a lengthy but intriguing discussion about violence and its function, how it is portrayed in media, and how it is validated and condemned in different contexts:

“When Saddam Hussain was executed in 2006… footage of the incident circulated widely via the internet. Major television networks ran the official video of the event right up until the moment of execution, including the footage of the noose being hung around his neck... a short time later, when shaky amateur footage circulated of the actual hanging, many news organisations ran parts of that, too… [this example] might seem like a far cry from a boxing match… but they form an inextricable part of the spectrum of ideas about violence that ripple through our society: about who orders, sanctions, tolerates or condemns that violence, and in what circumstances it occurs…”

There are many other chapters and sections which I have not done justice and should probably elaborate on but I think this is more than enough for now. The following quote will finish this much better than I can:

“Humans are not like animals in one critical way: humans have a moral code. We have the capacity to justify and think through the implications of our actions. But we have hidden the violence in our everyday lives from ourselves to avoid facing up to it. We are afraid of it, or repulsed by it, and so we refuse to come to terms with it… violence is a power relationship. This is critical to understanding it. To condemn all violence on principle is inherently meaningless, as violence itself has no meaning outside of its context. Similarly, to acknowledge that violence exists and is frequently accepted by society is not to sanction that acceptance. But an understanding of how violence functions in our society, and the moral rights and wrongs of that, cannot be gained by ignoring it, or brushing it aside, or dismissing it wholesale. It needs to be faced. This is what boxing taught me. I don’t pretend that it is everyone’s experience of the sport, but I can’t agree with the conclusion that combat sports should be condemned by dint of their engagement with violence alone. Violence explored in a consensual fashion with adequate measures against disproportionate power imbalances can be transformative. Perhaps a healthy, a different society, one in which equality and social justice are central to its structure rather than one organized primarily around competition and alienation, would transform sports like boxing – would find them to be useful tools to understand different aspects of human nature and power relations.”

Read more about the book and the author here: https://www.smh.com.au/sport/boxing/the-final-round-the-death-of-boxer-davey-browne-20200221-p54332.html

0 notes

Text

Joe Cinque's Consolation: A True Story of Death, Grief and the Law by Helen Garner

This book left me with more questions than answers (this is an observation, not a criticism).

The thought-provoking issues Garner explores in this book – imprisonment, grief, loss, drug use, the legal system and its “moral failures”, punishment, revenge, the fallibility of human memory, culpability, ethics, rehabilitation, mental illness, personal responsibility, and social class – inevitably raise endless questions. Ultimately, there is only one person – Anu Singh (one of the two defendants) – that knows exactly what unfolded before and after Joe Cinque lost his life. This is not unique to this story – in many crimes (and alleged crimes), the grief, trauma and pain of the survivor/victim and their family is compounded by the fact that the defendant is deceptive, evasive or dishonest for whatever reason, and unwilling to divulge the truth.

Garner is open from the outset about her own personal situation and how this colours her view. At a time when she is experiencing the breakup of her third marriage, a former colleague suggests she write about the trials and Garner begins following the story thereafter. Throughout the book, she is transparent about her doubts, confusion and despair at not only the legal process, but the experiences, recollections and admissions of the witnesses, the defendants and the families. She is in no way an objective observer, but she is honest about this. She admits Joe Cinque’s murder “wasn't a series of facts that [she] could be professional about, that [she] could seize and manipulate with [her] mind”. She admits feeling “helpless” and “paralysed”, thinking of little else but the story itself. The only way she knew how to deal with what she was feeling was to write about it. She writes honestly about her own biases, motivations and judgments. Initially, she recalls being driven by a deep curiosity, especially how and why a woman would kill. This morphs into what she admits was a “repelled fascination – even an identification – with Anu Singh”.

And so, she sits through the hearings and seeks out the voices of as many of those involved as she can, giving them an opportunity to share their side of the story publicly or anonymously. She includes the transcript of the call the defendant (Singh) made to emergency services. She includes the conversations she had – with the judge who oversaw the trials, and with the friends, families and associates of the defendants, and those of the victim. She is clearly disturbed by the voicelessness of Joe Cinque’s families in the legal proceedings. This drives her obvious desire to honour Joe Cinque and his family. She ensures their voices are heard and describes their grief and rage in a visceral but sensitive way. Her empathy for them is palpable. Some may argue that the relationship she forms with his family clouds her judgment. But I think the ethical minefield of some of the subject matter she explores would make it difficult for anyone to write objectively irrespective of their closeness to a victim’s family. And while Garner includes the observations and perspectives of Singh’s parents, her ability to provide balance is somewhat hindered by the fact that Singh herself refuses any invitation Garner extends. Granted, Singh’s perspective is included in the legal hearings, but this is vastly different from the information Garner could have gleaned had she had the opportunity to talk to Singh at all, let alone outside of the febrile and rigid environment of the court.

The gap between ethics and the law – and by extension that what is legal is not necessarily what is just – is something Garner finds confounding and discusses at length. When the judge states that “duty of care and duty to act are not the same thing” she admits having had no idea, having never thought about these things before. Garner persistently questions to herself throughout the hearing how and why people interpret culpability and personal responsibility the way they do:

“Did he [the judge] think of people as discrete bubbles floating past each other and sometimes colliding, or did he see them overlap, seep into each other’s lives, penetrate the fabric of each other? Where does one person’s influence end, and another’s responsibility begin?”

It is also obvious how conflicted and uncomfortable Garner feels about the idea of diminished responsibility in the context of Singh’s (claims of) mental illness. Both Singh’s parents are doctors and thus able to recruit expert witnesses to testify and present evidence that Singh has a personality disorder. The insanity defense that Singh’s team proposes is countered by the prosecution which argues Singh was narcissistic and calculating and completely aware of what she was doing. While the “diminished responsibility” is a partial defence only, in that the defendant still holds some accountability, Garner makes no illusion of where she stands – she is extremely skeptical of whether Singh’s claims of mental illness are genuine. Garner views Singh as inherently manipulative and feels the “diminished responsibility” argument and the evidence presented by the defence team does not account for what she describes as the “simple wickedness” that characterizes Singh’s behaviour. You also sense Garner’s dismay at the relative ease with which those of a certain background can navigate the justice system with respect to their profession, education and resources. Anu Singh’s legal studies undoubtedly allowed her to understand the technicalities and process of the hearing in a way that Cinque’s family couldn’t. It made me think back to Bryan Stevenson’s observation of the American criminal justice system that “treats you better if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent”.

The closeness of Garner to Joe Cinque’s family is most evident in the final chapters of the book, where Garner allows Cinque’s family and friends the space to reflect and remember. It is a poignant finish to a messy and devastating story. Ultimately, this book illustrates the deep complexities of the legal process and how deficient it is in providing justice and resolving the tangle of human predicaments that come before it.

A tiny handful of questions from this book:

What is the purpose of imprisonment? Is it punishment, or for rehabilitation? Does a longer sentence provide consolation, and to who, and why?

What is diminished responsibility? How do you measure it?

How would the case have played out in front of a jury had Singh chosen this avenue instead of judge only? Would the outcome have been different?

How would these events have played out in today’s media landscape? Trial by social media?

0 notes

Text

Catch and Kill by Ronan Farrow

Ronan Farrow accounts his experience as one of the investigative journalists who broke the story of serial sex offender Harvey Weinstein. While many are familiar with the story, Farrow’s position allows him to provide detailed insight on the story behind the story - the abuse of power by not only Weinstein, but his executives and various staff, right through certain media organisations and their executives. The apologists, the sheer number of people who implicitly or explicitly excuse abusive behaviour as “workplace misconduct” is harrowing. Farrow’s description of Weinstein as “simultaneously flattering & demeaning” underlines how perpetrators are predatory but in a twisted and manipulative way that deceives others.

The devastating nature of this manipulation and abuse is summarised well by this survivor’s description: “Everything was designed to make me feel comfortable before it happened. And then the shame in what happened was also designed to keep me quiet.”

The meaning behind “catch and kill”, and Farrow’s detailing as to how and why this story remained uncovered for so long is difficult to read. The pushback, intimidation, and threats Farrow and other journalists received is both infuriating and devastating. On one particular occasion, an executive pressures Farrow to drop the story, telling Farrow that he should not cover sexual assault as journalists should not cover the issue if they have family who have had experiences of sexual assault as it is a conflict of interest and clouds their judgment. ??? I don’t think it’s necessary to outline how and why that is messed up but it is and having lived experience of assault should not preclude someone from reporting or investigating a matter. It becomes clear how his sister’s experiences affected him and how it drove him to forge ahead with his reporting.

In contrast to the despicable characters he investigates, Farrow is open about his own views and motivations. For example, he discloses how earlier in his adulthood he selfishly tried to discourage his sister from speaking out about her experience. He expresses the regret, naivety and guilt he still feels about this. His awareness about his own past mistakes is refreshing.

He also broaches the issue of being a white male writing about women, consent and assault. While this presents an obvious challenge, he navigates the issue in a sensitive and honest way. He is transparent about the strengths of his position - the fame, resources, knowledge and education which he has and the access to opportunities, people and information that this affords him. However, he still put himself at immense risk to get the story out as well as to try to protect the survivors he speaks with.

This book should come with a warning. While there are stories of courage and hope, the complicit, manipulative and cruel behaviour of so many of the people in this story is a sickening and harrowing reminder of the pure evil that exists in society.

0 notes