Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

red herring press

is based in the easterly town of Great Yarmouth. It houses a risograph printer, used to publish and distribute local writing in the town.

Over the next bit of time, red herring press plans to run free sessions where people can learn to print (and use for their own projects), publish pamphlets of poetry and fiction by local people as well as on local history and currents, host readings and discussions and film screenings, start a multilingual collectively-run community newspaper/newsletter, open a (very small) local history and radical literature library, house a Writer’s Workshop group, and be a resource for local groups struggling against austerity and the consequences of capitalism.

* * * *

What does it mean to have ‘roots’ in a place? And what, and who, are those roots attached to?

There is immense focus on what has left Great Yarmouth over the years. The dwindling tourists, relocated art school, the closing of the last smokehouse, the diminishing fishing industry, shipbuilding industry, port; the high street increasingly derelict. Cheap studio and exhibition spaces are often used by artists living elsewhere, who rarely contribute to the town’s inner social or cultural life.

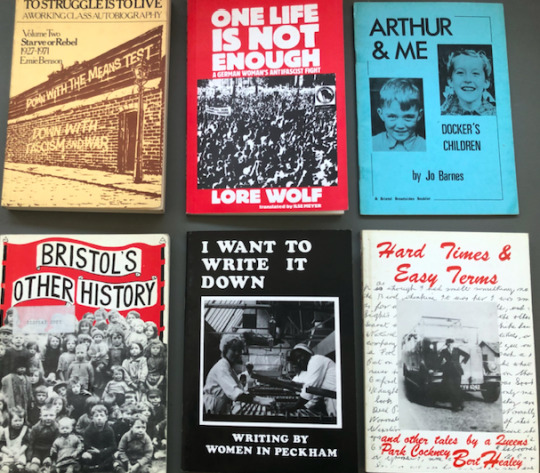

Despite the omnipresence of shops and businesses with seemingly little economic viability (the stall that sells only mushy peas, junk shops that open only between 2-4pm, the club that plays only Ministry of Sound CDs), there are no bookshops in Great Yarmouth. Why? Maybe cause of this widespread idea that a working class seaside town has no interest in, or need for, literature. That it is irrelevant: both literature to the town, and the town to literature. For the state and its bourgeois backscratchers, the ‘problem’ is seen as an impossibility to persuade or ‘educate’ working people to read books, rather than, as a Centerprise youth worker wrote in 1977: “seeing the issue as a result of two centuries of active suppression of working class people becoming too interested in politics and literature… The incalculable years of imprisonment spent by thousands of individuals in the last 150 years for daring to publish, or distribute writings on economics, philosophy, literature and other oppositional categories of thought.” This conscious strategy is clear in the government’s response to illiteracy: mobility scooters. This idea, and condescending responses around ‘the education of’ working people, led working class readers and writers in the 70s and 80s to set up their own bookshops and publishing presses across the UK, as documented by the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers.

And then the dangerous liberalism (disguised as militancy) of trying to claim that people don’t need books like they need food, housing, work, warmth - as if we can only aspire to what we ‘need’ and not beyond it. As if survival is all we’re asking for. As if reading, writing and distributing literature (whether read or listened to) wasn’t fundamental to struggles for better material conditions in apartheid South Africa, or 70’s Nicaragua, or the Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados (Unemployed Workers Movement) in Argentina, or the Diggers’ occupations for common land in 1600s England, or liberation struggles led by communist peasants in Palestine. As if literature cannot be specific to our own lives.

But culture isn’t a ‘right’, it’s a real living force - one we’re already making and participating in daily. When workers in Argentina were faced with the shuttering of their factories, they occupied them - creating spaces inside for a cultural centre, theatre and printmaking workshops, a free health clinic, a people’s lending library, an adult middle and high school education program, and a University of the Workers. Yet the argument that ‘books are necessary too’ often goes hand-in-hand with gentrification and displacement, under the guise of ‘cultural development’.

With this comes the (western) assumption that much writing - particularly poetry - cannot relate to the conditions of a place where there is high unemployment, poverty, prison leavers, homelessness, precarious immigration, flats in which people die from easy-to-avoid fires and a lack of carbon monoxide detectors, a place in which Universal Credit was trialled and the number of people accessing foodbanks multiplied. Where one day you see neo-Nazi tattoos branded on arms, a car flashing Confederate flags, and a postbox address for the National Front; and the next, people shouting in the faces of racists, community meals where English is exchanged for Portuguese is exchanged for Lithuanian is exchanged for Guinensi, where people embroider quilted scraps of material with “No to austerity”, “No to immigration controls”, “No to the closure of women’s refuges”.

A real distinction does exist between culture and conditions, though: there is a difference between funding arts projects and funding housing. Books can’t house or feed us, but can’t we demand both? And it’s not difficult to separate the everyday practice of culture, to which everyone has a claim, from a literary establishment and industry that has, as the qualified arbiter of taste, its own reasons for trying to persuade us otherwise. That posits ‘craft’ over the political and social principles of a poem: who cares if a poem is racist or homophobic if it’s well written?

We are drawn to writing for our own reasons and histories - distinct from a literary industry that publishes writing from outside official state culture only if it can be labelled and sold as ‘prison writing’ or ‘crazy writing’ or ‘poverty writing’ or ‘exotic writing’. Its designated ‘otherness’ and ‘unprofessionalism’ becomes its selling point, its marketability.

When a distorted and dying culture cannot provide any hopes for living in a different way, how can we build our own sustainable, amateur structures to write and read and share one another’s work?

Email: [email protected]

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/redherringpress/

Risograph printing: designed to be a high-volume, fast and low cost photocopier, riso machines work a bit like screen printing: a print image is burned onto a master sheet, which is then wrapped round a print drum. Ink is pushed through this stencil onto the paper. First produced in Japan in 1986, risos were popular with schools, churches, and political groups to mass produce posters, flyers, pamphlets and small books.

A risograph printer

Printers: Many printshops were set up in the 60s and 70s across the UK. Anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, anti-hierarchy, anti-racist, feminist, queer, anti-state. The radical printshop itself was not a new thing: printers of 'controversial’ material have existed in the UK - often at the risk of imprisonment - since at least the 17th century. Their aim was not just to produce politically radical materials but also to enact those politics through their non-hierarchical and collective organisational and production practices.

Books from the Trade Union Congress Library’s collection of publications from the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers.

1 note

·

View note