Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Reincarnation - Judaism✡️

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trutz Hardo

0 notes

Text

Carol Bowman

0 notes

Text

Brad Steiger

0 notes

Text

Dr. Michael Newton

0 notes

Text

Roy Stemman

0 notes

Text

Edgar Cayce

0 notes

Text

Annie Besant

0 notes

Text

Reincarnation occurs because we have lessons to learn about such things as love, compassion, charity, nonviolence, inner peace, and patience – it would be hard to master them all in only one life.

If your education isn’t finished, you’ll find yourself being born into another lifetime. There may be some choices involved, however, but apparently these choices are limited. For example, when you learn all about love, you don’t have to come back. Yet highly evolved souls often voluntarily choose to reincarnate to help teach others.

Dr. Brian Weiss

0 notes

Text

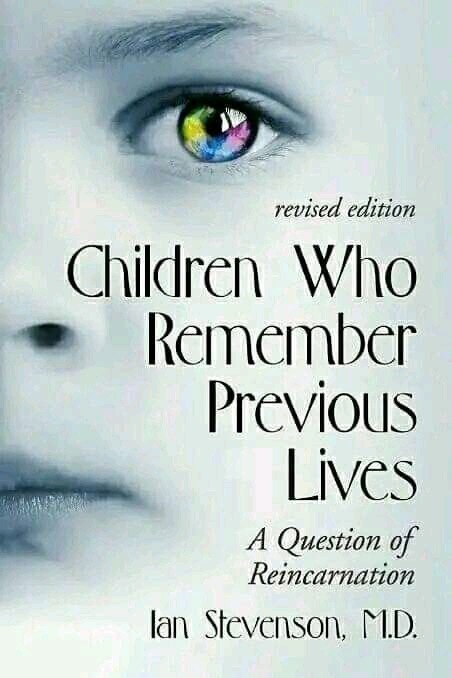

Reincarnation 📚📖 - Dr. Ian Stevenson

0 notes

Text

Video Nugget: A Neuroscientist Looks at Reincarnation with Marjorie Wool...

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

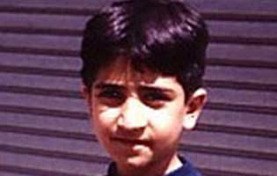

Nazih Al-Danaf (reincarnation case)

As a boy in Lebanon, Nazih Al-Danaf recalled the life of an armed bodyguard who died by assassination. The case was investigated by Erlendur Haraldsson, professor of psychology at the University of Iceland, and is notable for the large volume of detail later verified as accurate. The bodyguard’s widow and children became convinced that Nazih was their husband and father reborn.

The Druzes

Followers of the Druze religion are centered in Lebanon but also live in Syria, Jordan and Israel. Most authorities consider the religion a sect of Islam, dating back to the eleventh century, although some consider it an independent religion. Druzes follow different scriptures than mainstream Islam and do not observe its five central tenets. About ten percent of Druzes undergo religious training and are initiated into the religion’s secretly-kept scriptures, usually at an advanced age; they then dedicate themselves to a life of abstinence and virtue, and take on the title ‘Sheikh’ for men or ‘Sheika’ for women. Druze scripture draws from the Greek philosopher Plato, who wrote of reincarnation as a genuine phenomenon in the Republic and other works.

Reincarnation is a tenet of the Druze religion and children’s past-life memories are given more credence than in many other places, making the Druzes a rich source of reincarnation cases.

Fuad Assad Khaddage

Fuad Assad Khaddage was born in 1925 in Kfarmatta, Lebanon. He had two brothers, Ibrahim and Adeeb. After graduating from school, he worked at an orphanage, then began a thirty-year career at the Druze Centre (Dar El Taifeh) in Beirut. He served both as the centre’s manager and as one of three companions/bodyguards of the spiritual leader of the Druze community in the city. He was well-liked, and those who knew him recalled him being qabadai, a courageous, strong and honest person. He and his first wife Fida had eight children before divorcing. He fathered another five children by his second wife, Najdiyah.

On 22 July 1982 three men broke into the centre and shot Fuad to death along with two gate-guards. The attackers fled and were never identified. An autopsy report showed that Fuad had been shot twice at point-blank range, one bullet striking his head and the other striking the main artery in his neck, killing him instantly.

Nazih Al-Danaf

Nazih Al-Danaf was born on 29 February 1992. He was living with his family in Baalchmay, Lebanon, when researcher Erlendur Haraldsson and his Arabic interpreter and collaborator, Madj Abu-Izzeddin, first approached them, having heard about Nazih from another family. Now eight years old, Nazih was no longer speaking spontaneously of his previous life – as is typical of children past the age of five – and only did so when asked. By this time he could only recall portions of what he had recounted when younger. However, he still remembered his violent death and spoke of having been qabadai.

Statements by Nazih

According to Nazih’s mother, Naaim Al-Danaf, he was only eighteen months old when he began speaking in an unexpected way for such a young child. He would make statements such as, ‘I am not small, I am big. I carry two pistols. I carry four hand-grenades. I am qabadai. Don’t be scared by the hand-grenades. I know how to handle them. I have a lot of weapons. My children are young and I want to go and see them’.

Nazih also expressed a wish to go to his previous home to get papers regarding money he was owed. He told his mother, ‘My wife is prettier than you. Her eyes and mouth are more beautiful’. He also said this to most of his sisters, who are all older than he is.

Nazih’s mother recalled him saying he had lots of weapons and that he wanted to bring his father to his house and show them to him. He talked about ‘my friend the mute’ who could use a gun with one hand, having lost use of the other.

About his death, Nazih recounted: ‘Armed people came and shot at us. I also shot at them and killed one. We were shot and later taken by an ambulance’. He said he remembered being given anesthesia in the ambulance, and would point to a spot on his upper arm and say: ‘This is where they stuck the needle’.

Each of these statements was corroborated by varying numbers of the other nine family members – at least one and sometimes all nine. Nazih’s sister Sabrine said she heard him say that his previous name was Fuad.

Visit to Qaberchamoun

Nazih’s father, Sabir Al-Danaf, recalled him saying that his house was in Qaberchamoun, a small town about eleven miles away from his present home. Sabir had visited the town before but knew no one there. Nazih insisted on travelling there, sometimes even threatening, ‘If you don’t take me there I am going to walk there'.

When Nazih was six, his parents finally relented. On the way they drove past a road which Nazih said led to a cave. Qaberchamoun is at the convergence of six main roads: When they reached the intersection, Sabir asked Nazih which way to go. The boy indicated one road and told his father to drive along it until they came to another road that forked and went upward. Arriving at the road Nazih had described, they turned onto it but had to stop as it was steep and slippery due to water on its surface, as a young man was washing his car above. Nazih ran off in search of the house he had previously lived in, Sabir following.

Nazih’s mother Naaim and his siblings waited by the car, and in the meantime they made enquiries of the man washing his car. He was Kamal Khaddage, son of Fuad Assad Khaddage. He described the meeting to Haraldsson later. ‘They asked if I knew someone who had been shot, they did not know his name but he had carried handguns, hand grenades, and had owned a red car’ . Surprised that the description fit his father, Kamal called his mother, Najdiyah. Nazih and Sabir then joined the group.

Najdiyah recounted: ‘When Nazih came here I was picking olives in our garden some distance away. My children yelled at me that there was a boy who said that he was their father, and they wanted me to come and see if he would recognize me. I went to them and told his mother that my husband died in the war. When he [Nazih] saw me, he looked like he knew me, and looked up and down at me. Kamal then said to him, “Is she your previous wife or not?” Nazih smiled’.

Wanting to test whether the boy really was her deceased husband reincarnated, Najdiyah asked Nazih who had built the foundation of the entrance gate. Nazih answered, correctly, ‘a man from the Faraj family'. Inside the house, Nazih went into a room with a cupboard, indicating that he had kept his pistols and other weapons in it. This too was correct, including the spot in the cupboard where the arms had been placed.

Testing him further, Najdiyah asked him if she had had an accident when they had lived in another village. He answered that while picking pine cones for her children to play with, she had slipped on plastic nylon, dislocating her shoulder. This had happened in the morning, when Fuad’s father Assad had been present. After returning from work, Fuad had taken her to the doctor, who had put a cast on her shoulder. All these details were correct. Najdiyah asked Nazih how their young daughter had been made severely ill; he answered, correctly, ‘She was poisoned by my medication and I took her to the hospital'.

Najdiyah also reported that Nazih had asked her whether she remembered certain incidents, such as the family being helped on their way to Beirut by Israeli soldiers who charged their car battery, and the night she locked Fuad out of the house because he was drunk, forcing him to sleep on a rocking sofa. He asked to see the barrel in the garden he had used to teach her to shoot, again remembering accurately.

By the end of the visit, the boy’s extensive knowledge of Fuad’s life had convinced Najdiyah and the five children that Nazih was the reincarnation of Fuad.

Recognitions by Nazih

Najdiyah reported that she showed Nazih a photograph of Fuad, asking who it was. He answered, ‘This is me, I was big but now I am small’.

Nazih and his current-life family then visited Fuad’s younger brother Adeeb, now called Sheikh Adeeb since he had been initiated into the Druze religion, at his house in Kfarmatta. Sheikh Adeeb recounted: ‘I saw a boy running towards me who said, "Here comes my brother Adeeb", and he hugged me. I remember it was wintertime and Nazih said, "How do you go out like this, put something on your ears". Then he told me, "I am your brother Fuad’’ '. Asked for proof, Nazih said he had given Adeeb a handgun as a gift, correctly identifiying it as a Checki 16, a model that is uncommon and considered precious in Lebanon.

Nazih then correctly identified Fuad’s father’s house and Fuad’s own first house, stating that the wooden ladder in it had been made by Fuad. His first wife, Fida, still lived there, and Nazih correctly identified her as ‘Im Nazih’ (‘mother of Nazih’) since her first-born son by Fuad was also named Nazih. Shown a photograph of Fuad with his two brothers, he correctly identified all three men, as well as their father in another photo. Later Sheikh Adeeb visited Nazih back in Baalchmay, bringing a handgun and asking if it was the one Fuad had given him. Nazih correctly answered no.

Sheikh Adeeb recalled that the reunion was quite emotional, with many hugs and tears.

Behavioural Signs

Nazih’s family noticed that he was unusually fearless for a young child. He displayed other behaviours reminiscent of Fuad: When he saw a cigarette box, he would sometimes want to take a cigarette out and smoke it; he also wanted whisky if he saw someone else drinking it. These behaviours were particularly marked at the same time he most frequently spoke about the past life, before the visit to Qaberchamoun.

Case Investigation

Haraldsson made six journeys to Lebanon between August 1988 and March 2001 in order to conduct a psychological study of children who remember past lives. Out of nineteen boys and eleven girls in the Druze community, he chose several for detailed investigations, including Nazih. In his case report,[Haraldsson & Abu-Izzeddin (2002). See also Haraldsson & Matlock (2016). Haraldsson wrote, ‘The exceptional features of this case (e.g., the number of witnesses to his statements before an attempt was made to find a deceased person) seemed in particular to deserve a thorough investigation’. Haraldsson first met Nazih in May 2000, when he was eight years old.

In his investigation, Haraldsson used methodology developed by Ian Stevenson. During three trips to Lebanon in 2000 and 2001, he and Abu-Izzeddin interviewed Nazih’s mother and father, six sisters and one brother. Each was interviewed alone where possible, and asked only to report what they had witnessed personally, not what others had said they had witnessed. Each person was interviewed multiple times, months apart.

The next step was to determine how much the case had already been verified prior to investigation, and critically examine that verification by interviewing the family and associates of the deceased person Nazih claimed to have been. On two occasions, Haraldsson and Abu-Izzeddin visited Fuad’s family and took careful notes.

The final step was to check the accuracy of each statement made by Nazih, as described by his family, by comparing it with the known facts of Fuad’s life, circumstances and character, as recalled by his family and associates. Haraldsson and Abu-Izzeddin travelled from Baalchmay to Qaberchamoun twice, in order to recreate the journey that Nazih’s family had taken him on to meet his former family.

Both Najdiyah and Adeeb tested Nazih’s knowledge in an appropriately sceptical way, eliciting the additional statements which convinced them he really was Fuad reborn.

Nazih's Later Life

Haraldsson reported that after their reunion the two families continued an affectionate relationship with occasional visits. Looking back fifteen years later, he commented, ‘No case that I have investigated equals it in how perfectly the remembered statements fit the facts in the life of the previous personality.’ ¹

Literature

Haraldsson, E., & Abu-Izzeddin, M. (2002). Development of certainty about the correct deceased person in a case of the reincarnation type in Lebanon: The case of Nazih Al-Danaf. Journal of Scientific Exploration 16, 363-80.

Haraldsson, E., & Matlock, J.G. (2016). I Saw a Light and Came Here: Children´s Experiences of Reincarnation. Hove, UK: White Crow Books.

Endnotes

1.Haraldsson & Matlock (2016), 26.

0 notes

Text

Bishen Chand Kapoor (reincarnation case)

In this early twentieth-century Indian reincarnation case, the initial investigator created a written record of the child subject’s memories before attempts at verifications were made, and a second investigator followed the child’s subsequent progress until middle age.

Bishen Chand Kapoor

Bishen Chand Kapoor was born on 7 February 1921 in the city of Bareilly in northern India. He was nicknamed Vishwa Nath, as his mother had visited the temple of Vishwa Nath shortly before becoming pregnant. At ten months he began to utter a word that sounded like ‘pilvit’ or ‘pilivit’. As his speaking ability improved, he began talking about a previous life in Pilibhit, a large town about fifty kilometres distant, giving his past-life name as Laxmi Narain, along with other details.

Investigations

In 1926 an account appeared in a newspaper in northern India, in which an Indian lawyer Kr Kekai Nandan Sahay described his son’s past-life memories and their verification by investigation. This prompted other people to come forward with similar accounts, some of which Sahay set out to investigate.1 One was that of Bishen Chand Kapoor.

On 29 June 1926, Sahay visited Bishen’s family and interviewed the boy, then five and a half years old, taking notes. He then persuaded Bishen’s father to take the boy to Pilibhit to try to verify the statements. The boy recognized buildings and apartments he had previously known, and his old classroom. He also recognized his previous father, Har Narain, and his previous self, Laxmi Narain, in a photograph. He demonstrated drumming skill on a pair of tablas, an instrument he had not hitherto seen.2

On 22 August Sahay took Bishen to visit Laxmi’s mother in Bareilly. She tested him with questions, a dialogue that Sahay recorded. In 1927, Sahay wrote a pamphlet which included several reincarnation cases he investigated in the course of that year, including that of Bishen Chand, whom he referred to by the pseudonym Vishwa Nath.3

Three decades later, the pioneer reincarnation researcher Ian Stevenson came across Sahay’s pamphlet and decided to investigate the case further. In 1964, he interviewed Bishen’s older brother, sister-in-law, and older sister in Bareilly, then Laxmi Narain’s cousin in Pilibhit, while his assistant in India, P Pal, interviewed Bishen’s father. Finally Stevenson had a long conversation with Bishen Chand himself in 1969, and two more in 1971 and 1974.

As he habitually did in such cases, Stevenson checked carefully whether information about Laxmi Narain could have reached Bishen Chand through normal channels. He learned that Bishen’s family had no connections with Pilibhit or the Narain family, although they had passed through the location on train journeys without stopping. An uncle of Laxmi Narain lived fairly close to Bishen Chand’s family in Bareilly, and his mother moved there also in 1926. However, Stevenson notes that neither Sahay nor Bishen Chand’s father had approached them first to verify the child’s statements, indicating that the family was not aware of their presence and that information could not have come to Bishen from them. He also points out that Bishen Chand had begun to mention Pilibhit at ten months, before he could have come into contact with people outside the family without the parents knowing.

Stevenson published the case in 1975 in the first book of his Cases of the Reincarnation Type series,4 including Sahay’s pamphlet almost in full, with explanatory annotations.

Stevenson considered this case important because statements made by the child were recorded in writing prior to verifications being attempted. He was able to acquire a great deal of information both about the previous person and about the subject’s later life and development, as Bishen was middle-aged when Stevenson investigated the case. The case also shows typical characteristics of those in which a child born into poverty recalls the life of a wealthy person.

Laxmi Narain

Stevenson was unable to meet any member of the Narain family who had known Laxmi Narain. Instead, he relied on information given by Sahay, by relatives of Bishen who had spoken with the Narain family, and by others who had known Laxmi Narain.

By their accounts, Laxmi Narain was the spoiled only son of a wealthy landowner, Har Narain. He dropped out of school at seventeen or eighteen after the death of his father, having attained only sixth grade, though he continued with private education or self-instruction. Left a substantial inheritance, Laxmi Narain freely indulged his appetites for good food, fine clothes, beautiful women and drink. He worked for the railway service for an undetermined amount of time.

He never married but was possessively attached to a prostitute named Padma. When he saw another man come out of her apartment, he seized a gun from his servant and shot the man dead. He went into hiding but appears to have escaped justice mainly by means of bribes. Sahay’s report did not mention the murder but it did discuss a related lawsuit, from which Stevenson calculated that the incident occurred in 1918. Laxmi Narain moved to another town, Shahjahanapur. He died on 15 December 1918, aged 32, of fever and lung trouble, having been ill for five months.5 He had spent so much of the family’s fortune that his mother had to move in with her brother in Bareilly.

Laxmi Narain’s contemporaries reported that he was very generous; he sometimes gave his own food to beggars, and once gave a Moslem watch repairman a large sum to launch a business. He was also strongly religious, at least part-time: according to his mother he would seclude himself in his shrine-room to worship for ten to fifteen days at the start of the month, then throw himself just as passionately into debauchery for the remainder, before repeating the cycle.

A maternal uncle of Laxmi Narain told Sahay that Laxmi too had remembered a previous life, up to the age of six years, saying that he had come from Jehanabad. No attempt at verification had been made, as the parents had wished to keep his past-life memories secret.6 Many years later, Bishen Chand claimed to Stevenson that the past life he had remembered as Laxmi was that of a rajah’s son, but he no longer retained any memories of it. (Stevenson investigated three other cases of children who recalled being people in previous lives who themselves recalled previous lives: Timothy Curran, Maung Aung Myint and Mounzer Haïdar.)

Bishen Chand’s Statements

By Stevenson’s count, Bishen Chand made 48 statements, 21 of which were recorded by Sahay before Bishen met relatives of Laxmi Narain. Some were slightly inaccurate: for instance he identified Har Narain, Laxmi’s father, as his uncle. Others were likely to be true, but could not be verified, while others were only partially verified, for instance that he had been treated by an Ayurvedic doctor named Hanumant Vaidya: an Ayurvedic doctor of that name was found to have worked in Shahjahanapur, but by this time was deceased.

Statements made by Bishen Chand that were verified as correct for the life of Laxmi Narain (named in Stevenson’s tabulation) included:7

•he had belonged to the Kayastha caste (Bishen Chand belonged to the more humble Kattri subcaste)

•he lived in Pilibhit

•his father was a zamindar (wealthy landowner)

•his father died before he did, and a large crowd attended the funeral

•he studied up to the sixth class in the government school, which was near the river that flows past Pilibhit

•his English teacher in the sixth grade was fat and bearded

•he knew Urdu, Hindi and English

•his house had two storeys

• he liked to watch nautch girls (women who performed songs and dances)

•he funded the launch of the business of a Moslem watch dealer in Pilibhit

•his mistress’s name was Padma

•his ‘uncle’ Har Prasad had a green house (the term ‘uncle’ could be used for a close friend of one’s father, which Har Prasad was)

•Har Prasad’s mistress was named Hero

•he had a neighbour named Sunder Lal, whose house had a green gate

•he competed in kite flying with Sunder Lal

•he worked for a time for the Oudh Railway

•his servant was called Maikua, a member of the Kahar caste (mostly servants and cooks)

•his bed was elegant, with a heavy covering and four pillows8

•he won a lawsuit against some relatives (there were in fact several lawsuits)

•he shot and killed a man he saw coming out of Padma’s house

•he obtained a job in Shahjahanapur

•he died in Shajahanapur

Bishen made a number of recognitions, including: himself and his father in a photograph; Sunder Lal’s house; and the ruins of the house in which he had lived. Notably, he also identified a room in the house where, he claimed, Har Narain had buried some treasure. He could not indicate the precise place, but a search later unearthed a stash of gold coins.

Bishen also pointed out the houses of Lalta Prasad, a merchant, and Ismail, the watch dealer whose business he had helped start.

Behaviours

Between the ages of three and seven, Bishen Chand talked about his past life every day, according to his older sister. He also displayed behaviours that matched the personality of Laxmi Narain, and that were entirely inappropriate to his present circumstances. He reproached his father for his poverty, demanded money and cried when his demands were refused, derided the modesty of the house, tore off his cotton clothes and demanded ones made of silk. He once said, ‘even my servant would not take the food cooked here’. The family was strictly vegetarian, as customary for their caste, but at the age of five or six he began to ask for meat, and took to eating it secretly. When his sister caught him drinking medicinal brandy, he said, ‘I am used to drinking’.

When he was age four, his father took him on a train journey that passed by Pilibhit. When the stop was announced, he demanded to get off, saying he ‘used to live here’, and cried when denied.

Aged less than five and a half years of age, Bishen said to his father, ‘Papa, why don’t you keep a mistress? You will have great pleasure from her’. He once told a witness who asked him about his past-life wife and children: ‘I had none. I was steeped in wine and women and never thought of marrying’.

In this same period of his life, between three and seven, he would proudly relate how he murdered his rival for Padma’s favours, boasting about how family influence had spared him punishment. He was known for having a quick temper.

Bishen demonstrated some xenoglossic ability in being able to read Urdu before he was taught it, using two Urdu words in particular that were typical for upper-class residents of Pilibhit. When Laxmi Narain’s mother visited him in Bareilly, he recognized her and addressed her using the style of epithets that Laxmi Narain had used.

Bishen showed great affection to Laxmi’s mother, preferring her to his own. He often tried to persuade his father to let her live with his family, and visited often when she stayed with her brother in Bareilly. He stayed in touch with her until he was fifteen.

As a child, Bishen was visited by his past-life mistress Padma, and immediately sat in her lap. He retained old grudges, disdaining female relatives of a person he had sued, and mocking a former neighbour who had acquired the honorary title of ‘Rajah’. He not only recognized his former house, but walked in it as if it still belonged to him.

Later Development

Bishen Chand began to lose his past-life memories at age seven, retaining into adulthood only the one of having committed a murder. He gradually adjusted to his current circumstances and abandoned past-life behaviours such as insisting on silken clothes. However, in middle-age he still bucked the vegetarianism of his caste, continuing to eat meat and fish outside the home. As an adult, he earned a modest living as an excise officer, dressed plainly and eschewed his past-life excesses. He retained a quick temper but was not violent and would sometimes weep in remorse for losing his temper.

At 23 years old, he happened to meet Padma at his office, and was so overcome with emotion that he fainted. That evening he went to her home with a bottle of wine, intent on renewing old pastimes. Her response was not what he wished. ‘I am an old woman like your mother’, she said, smashing the bottle. ‘Please go away. You lost everything in your previous life. Now you want to lose everything again’. He married about two years after this episode, and he and his wife were still together in his middle age.

As Bishen Chand aged, he reflected often on the contrast between his current and previous lives. He now believed that he had been born into poverty as punishment for past-life actions, especially the murder, the only incident he still recalled. In a general way he still remembered having enjoyed more freedom and pleasure in his life as Laxmi Narain, but now more with remorse than anger. At the age of 48, he desired greater material wealth only to be able to exercise generosity, and expressed a wish for superior intelligence in his next life, rather than wealth. Stevenson writes: ‘I felt myself in the presence of a person who had learned that material goods and carnal pleasures do not bring happiness’.9

Literature

Sahay, K.K.N. (1927). Reincarnation: Verified Cases of Rebirth After Death. Bareilly, India: Gupta.

Stevenson, I. (1975). Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Volume I: Ten Cases in India. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.

Endnotes

1.Sahay (1927), 9.

2.Sahay (1927), 9-12.

3.Full case report: Sahay (1927), 9-15.

4.Full case report: Stevenson (1975), 176-205. All information in this article is drawn from this chapter except where otherwise noted.

5.Sahay (1927), 12.

6.Sahay (1927), 12.

7.Stevenson (1975), Table 8, 186.

8.Sahay (1927), 13-14; see Stevenson (1975), 184-5.

9.Stevenson (1975), 205.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Author: KM Wehrstein

Word count: 2,300

Created: 3rd November 2017

Last updated: 22nd October 2024

May be cited as:

Wehrstein, KM (2017). ‘Bishen Chand Kapoor (reincarnation case)’. Psi Encyclopedia. London: The Society for Psychical Research. <https://psi-encyclopedia.spr.ac.uk/articles/bishen-chand-kapoor-reincarnation-case>. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

0 notes

Text

"I Will Return As Your Next Son"

Victor Vincent was a Tlingit fisherman. During the years before his death he visited his niece Corliss Chotkin Sen more and more frequently. She was the daughter of his sister, Gertrude. He seemed to be very fond of his niece and especially their youngest daughter whom he believed to be the reincarnation of his sister Gertrude. In other words, the daughter was her own grandmother, who had been Victor Vincent’s sister.

About a year before his death Victor told his niece the following, “I will return as your next son. I hope I won’t be stuttering as much then as I do now. Your son will bear these scars. He lifted his shirt to reveal a scar on his back, which had remained visible years after having had an operation. There were also needle marks clearly visible around this scar. Then Victor pointed to another scar from an operation, which he had on his nose. He said that this too would identify him in his next life as her son. He also told his niece why he wants to be reborn to her. “I know that with you I will be well looked after. You won’t go off getting drunk.” Sadly there were many alcoholics among his relations for alcohol had become a curse among his people. In many ways modern living had separated them from their traditions or brought them into conflict with them. On my travels around the world I have experienced many such examples of devastation where modern influences have had disastrous effects on indigenous people.

Eighteen months after Victor’s death, Chotkin Sen gave birth to a boy, who was given his father’s name Corliss Chotkin junior. His parents were convinced that their son was Uncle Victor reborn, since he was born with exactly those scars he had shown them before his death, namely on his nose and back.

When he was 13 months old his mother tried to help him pronounce his name Corliss. The boy suddenly pointed to himself saying, “Me Kahkody!” This had been the name of Vincent’s tribe. Since he corrected every one who called him Corliss with the name Kahkody, this name finally stuck. When an aunt visited his mother and was told about Corliss being Vincent reborn, the woman said, “I knew it. After his death Victor appeared to me in a dream and said that he was now incarnating in your body so that he could be your son.” The mother had waited in vain for such a dream since it was very common among them for the souls seeking to reincarnate to announce their arrival in a dream.

When Corliss was two years old he travelled to the neighbouring seaside town with his mother. Unexpectedly they met a young woman, and before any words were exchanged the little boy called out her name. He was so happy he jumped with joy calling her by her Tlingit name. For this woman had been his stepdaughter in his previous life. A little later the boy caught sight of a man among the pedestrians, pointed at him and said to his mother, “There’s my son William.”

A year later Mrs. Chotkin took her son along to a big Tlingit gathering. Among the many people present he saw an elderly woman and said, “That’s the old dame. That’s my Rose.” This woman had been his previous wife, whom he used to call ‘old dame’ when he was Victor. In the years that followed Corliss recognised several of Victor’s relatives and friends, calling them not only by their Christian names, but also by the name of the tribe they belonged to.

Corliss once talked about something he had experienced as Victor. One day he had taken his fishing boat far out into one of the wide coves when his motor suddenly failed. He was tossed about in the waves having no control. When he saw a boat he put on a Salvation army uniform which he had on board since he thought that no one would take any notice of a waving Indian in a boat. To his amazement the boat came closer and took his boat in tow. Uncle Victor had told the story in the presence of Mrs. Chotkin a long time ago, but she was sure that no one could have told Corliss about it. Another time he said to his mother, “When the ‘old dame’ and me used to visit you we always slept in this room.” Saying this he pointed to a room which was now used for other purposes. This too was true.

Many such memories would surface in him unexpectedly. When he was nine his memories of his previous life began to disappear. When Stevenson interviewed Corliss at the age of 15, the boy claimed not to be able to remember anything from his past life. All too often the diligent investigator Stevenson has failed to meet children at an age when they still had direct access to memories of their past lives. Therefore in many cases he has had to rely on other people telling him things afterwards. Most of the children who remember past lives begin to talk about these when they are about two years old. But after the age of six the memories usually become less frequent, and by the age of nine are often completely gone.

Mrs. jockey Chotkin had always combed her son’s hair to the back. Corliss always combed it to the front just like his deceased great-uncle used to do. He also had a stutter like him, just as he had mentioned to his niece in his previous life. When he was ten years old he started having speech therapy. This seemed to have cured him because when Stevenson spoke with him he no longer stuttered. Victor had been a very religious man, which was why he had joined the Salvation army. Corliss also developed similar views on life, which became noticeable when he avidly started reading the Bible and later decided to look for a Bible school. Victor had been a keen fisherman. He used to say that he would be happy to spend all his life out at sea. He had also been very good at fixing boat engines and anything involving the use of his hands. He could not have inherited this from his father since he apparently had no such skills. Corliss was also left-handed just like Victor had been.

Stevenson always inspected extremely carefully the birthmarks that babies were born with. The mark on the base of Corliss’ nose was from a small operation that Victor had undergone in hospital in 1938. This mark was still visible after the operation, during which they had removed the right tear duct. But the larger mark on the back was not typical of a usual birthmark. It was about 2.5 centimetres long, dark in colour, slightly raised and about 0.5 centimetres wide. Stevenson writes, 8 “Along the edges of the main scar I could see small round marks on both sides. Four of these were in a straight line along one side like needle wounds received during surgery.” Corliss must have scratched the scar for it was often inflamed. Stevenson had the hospital send him a detailed account of Victor Vincent’s operation. Corliss’ scar on his back perfectly matched the one Victor had been left with after his surgical operation. This case presents us with clear evidence in favour of reincarnation.

Source : Children who remember previous lives : a question of reincarnation (Dr. Ian Stevenson)

0 notes

Text

The Girl Who Remembers 10 Previous Lives | Case of Reincarnation

youtube

0 notes

Text

Norman Mailer

0 notes

Text

Dr. Jane Goodall

0 notes