Text

Introduction to “I’m Dysfunctional, You’re Dysfunctional: The Recovery Movement and Other Self-Help Fashions”

By Wendy Kaminer

From I’m Dysfunctional, You’re Dysfunctional: The Recovery Movement and Other Self-Help Fashions (Addison-Wesley, 1992)

Introduction

This is not a book about my life or yours. It does not hold the secret to success or salvation. It won’t strengthen your self-esteem. I don’t think it will get me on “Oprah.”

My critique of the recovery movement and other self-help fashions does not reflect my personal experiences (although it surely reflects my temperament). I am not and never have been a convert to recovery or even an occasional consumer of popular psychology, religion, or wellness books. I have attended support groups only as an observer, not as a participant. I have read self-help books only as a critic, not as a seeker, and I was rarely engaged by the books that I read (one hundred or so), except as a critic. Whether this makes my analysis more or less worthwhile depends on whether you value the authority of experience more or less than the authority of research and reflection.

Writing on the basis of research and reflection, not experience, I’m writing counter to the Alcoholics Anonymous, twelvestep tradition currently in vogue. “Hi, I’m Wendy, and I’m a recovering alcoholic, overeater, drug abuser, shopper, or support group junkie;” I’d be required to confess if I were writing a recovery book, offering advice. Instead I have only opinions and ideas; so although I imagine myself engaging in a dialogue with my readers, I don’t imagine that we constitute a fellowship, based on shared experiences. Nor do I pretend to love my readers, any more than they love me and countless other strangers.

Perhaps because I have never trusted or desired protestations of affection or concern from strangers and mere acquaintances, I have never been attracted to support groups. It is often said that support groups offer community, and for people who attend the same group regularly and befriend other members that may well be true. But newcomers to meetings are considered part of the community too, so it is not necessarily based on friendship, if by friendship we mean bonds that build and strengthen over time. A twelve-step group seems a sad model for community. Testimony takes the place of conversation. Whether sitting in circles or lined up in rows, people take turns delivering monologues about themselves, rarely making eye contact with any of their listeners. Once, at an AA meeting I attended, a man testifying from the front row turned to look at us while he spoke, scanning our faces, seeking contact. Like everyone else I looked away; his behavior seemed inappropriate.

My own notion of intimacy does not include prurience — the exchange of secrets between strangers. My vision of community is shaped by an ideal of mutual respect between citizens and neighbors and a shared sense of courtesy and justice, but not love. “Not all men are worthy of love,” Freud wrote, debunking the religious ideal of unconditional love on which the recovery movement is based.1 God loves us in spite of our flaws, as we must love each other, today’s popular Protestant writers confirm. Or, as recovery experts might say, the love that discriminates, which Freud described, is a form of abuse. Like an Old Testament patriarch, Freud might be a model for an abusive, “shaming” parent.

Although the literature about recovery from addiction and codependency borrows heavily from family systems theory and seems, at first, an offshoot of pop psychology, it’s rooted most deeply in religion. (Codependency is the disease from which everyone — alcoholics, drug abusers, shoppers, and sex addicts — is trying to recover.) The ideology of recovery is the ideology of salvation by grace. More than they resemble group therapy, twelve-step groups are like revival meetings, carrying on the pietistic tradition.

The religiosity of the recovery movement is evident in its rhetorical appeals to a higher power and in the evangelical fervor of its disciples. When I criticize the movement I am usually accused of being “in denial;” as I might once have been accused of heresy. (There are only two states of being in the world of codependency — recovery and denial.) People who belong to twelve-step groups and identify strongly as addicts often turn on me with the self-righteous rage of religious zealots defending their gods.

Yet I have no power over them and want none. I’m not questioning their freedom to indulge in any religion or self-help movement. I’m not marketing a competing movement or exhorting them to do anything in particular with their lives. If they’re happy in recovery, why do they resent and take personally the skepticism of strangers?

In fact, I don’t intend my indictment of the recovery movement to be an indictment of every recovering person or even a comment on the movement’s role in their lives. It is impossible to know how everyone in it uses this movement, interpreting or screening its messages to suit themselves. (It is equally impossible to know how many people are helped or hurt by individual therapy.) Countless people move in and out of support groups and read self-help books with varying degrees of attentiveness, skepticism, and naiveté. Some people say they’ve been helped by twelve-step groups, some say they’ve been hurt, and many have probably been affected indifferently.

This is not to minimize the popularity of the recovery movement, which, after all, is what makes it worth reviewing. Recovery gurus, such as John Bradshaw, have large and loyal followings; although sales of recovery and codependency books may have peaked, they are still in the millions. But, in the end, the testimonials of several million satisfied consumers are not exactly relevant to my critique. I’m not commenting on the disparate effects of the recovery movement or any other self-help program on the millions of individuals who partake in it. How could I? The individual effects of any mass movement are impossible to quantify. I’m commenting on the ideology of the recovery movement and its effect on our culture.

In questioning the collective impact of self-help trends, I’m making the unfashionable assumption, bound to irritate many, that it is still possible to talk about “our” culture in a self-consciously multicultural age. I’m assuming that Americans of different races, ethnicities, religions, genders, degrees of physical ablement, and socioeconomic classes may be affected by the same cultural phenomenon, such as television, celebrity journalism, confessional autobiographies, consumerism, and the preoccupation with addiction, abuse, and problem-solving techniques. Precisely how each group, tribe, or subculture is affected by these phenomena I leave to poststructural scholars to decide.

I’m not assuming, however, that self-help movements always represent every group of Americans they affect. Mainstream, mass market self-help books are generally written and published by whites and tend to target mostly white, broadly middle-class audiences. There are also, no doubt, historic racial divides in the self-help tradition, reflecting racial divides in society. My own reading of turn-of-the-century African-American self-improvement literature and conversations with African-American scholars lead me to suspect that there is an African-American tradition oriented more toward communal, than individual, development; analogous self-improvement efforts among whites tended to emphasize the individual’s progress up the ladder of success and salvation. Given the legacy of slavery and discrimination, it’s not surprising that African-American self-help would focus more on “lifting the race.” But diversity of opinion and ideals within racial and ethnic groups makes it difficult to label self-help movements distinctly black or distinctly white, the tradition of community activism and volunteering cuts across American culture, and the larger self-help tradition involving personal and communal development is a fairly pluralistic one. Early twentieth-century African-American leaders Marcus Garvey and Father Divine adopted some classic positive-thinking ideals — both were proponents of New Thought, a loose collection of beliefs about mind power that emerged in the nineteenth century. Today, Oprah Winfrey is a most effective proselytizer for recovery.

The divide in the self-help tradition that interests me is not demographic (racial, ethnic, sexual, or economic) but ideological: I’m distinguishing between practical (how to do your own taxes) books and personal (how to be happy) books. Of course, sometimes the practical and personal converge: Saving money on your taxes may make you a happy person. A diet book may offer helpful, practical advice on how to eat, while reinforcing cultural ideals of slimness and promising to boost your self-esteem. But if few books are purely personal or purely practical, some are clearly more personal. It is a strong emphasis on individual, personal, or spiritual development that connects the self-help ideals I’m reviewing and composes a tradition. It is that tradition I’m critiquing. How-to books may be appropriate guides to fixing your car, caring for your pet, or even organizing a political campaign. They are fundamentally inapposite to resolving individual psychic or spiritual crises and forming an individual identity.

The self-help tradition has always been covertly authoritarian and conformist, relying as it does on a mystique of expertise, encouraging people to look outside themselves for standardized instructions on how to be, teaching us that different people with different problems can easily be saved by the same techniques. It is anathema to independent thought. Today’s popular programs on recovery from various (and questionable) addictions actively discourage people from actually helping themselves. (Self-help is usually a misnomer for how-to programs in identity formation.) Codependency experts stress that people who shop or eat or love or drink too much cannot stop themselves by solitary exertions of will. Addiction is considered a disease of the will; believing in self-control is one of its symptoms.

That the self-help tradition is rarely described in these terms — as conformist, authoritarian, an exercise in majority rule — is partly a tribute to the power of naming. How could anything called self-help connote dependence? But the authoritarianism of this tradition is cloaked most effectively in the power of the marketplace to make it seem freely chosen. Choice is an American article of faith (as the vocabulary of the abortion debate shows; even antiabortion activists use the rhetoric of choice); and we exercise choice, or enjoy the illusion of it, primarily in the marketplace. We choose from myriad brands of toothpaste and paper towels in the belief that they differ and reflect our own desires. We choose personal development experts, absorbing their maxims and techniques and making them our own.

With luck or good judgment, some readers find guides who are helpful or who at least will do no harm. The best self-help books are like good parents, dispensing common sense. Many more are like superfluous consultants, mystifying the obvious in jargon and italics to justify their jobs. “The first step in dismantling the kind of thinking that reinforces misery addiction is to identify what I call miserable thoughts,” Robert A. Becker, Ph.D., announces in Addicted to Misery.2 Experts package inanities as secrets that they’re generously willing to divulge. In the best-selling Secrets About Men Every Woman Should Know, Beverly DeAngelis clears up such mysteries as “why men don’t like to talk and have sex at the same time.”3 The answer, she says, simply restating her question, is that “men have a more difficult time expressing themselves and simultaneously performing a task than women do.” What is the basis for this bold assertion about gender difference? There is only DeAngelis’s claim to expertise — her Ph.D and special insights into humankind. She is, after all, the author of How to Make Love All the Time.

This earnest fatuity that you find in self-help books is what makes them so funny. That millions of people take them seriously is rather sobering. We should be troubled by the fact that the typical mass market self-help book, consumed by many college-educated readers, is accessible to anyone with a decent eighth-grade education. We should worry about the willingness of so many to believe that the answers to existential questions can be encapsulated in the portentous pronouncements of bumper-sticker books. Only people who die very young learn all they really need to know in kindergarten.*

Some will call me an elitist for disdaining popular self-help literature and the popular recovery movement; but a concern for literacy and critical thinking is only democratic. The popularity of books comprising slogans, sound bites, and recipes for success is part of a larger, frequently bemoaned trend blamed on television and the failures of public education and blamed for political apathy. Intellectuals, right and left, complain about the debasement of public discourse the way fundamentalist preachers complain about sex. Still, to complain just a little — recently the fascination with self-help has made a significant contribution to the dumbing down of general interest books and begun changing the relationship between writers and readers; it is less collegial and collaborative than didactic. Today, even critical books about ideas are expected to be prescriptive, to conclude with simple, step-by-step solutions to whatever crisis they discuss. Reading itself is becoming a way out of thinking.

This book will not conclude with a ten- or twelve-point recovery plan for the “crisis of codependency;” or the “codependency complex,” or any other “self-help syndrome.” If there is an easy way to get people to think for themselves, I haven’t yet discovered it. (The hard way is education.) This book is not what publishers call prescriptive. As a writer and not a politician, I’ve always felt entitled to raise questions for which I have no answers, to offer instead a point of view.

*Robert Fulghum’s All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten was the number one best-seller among college students for the 1989-1990 academic year. Fulghum was chosen as commencement speaker at Smith College in 1991 and offered an honorary degree, to the horror of at least a few alumnae (Edwin McDowell, What Students Read When They Dont Have To New York Times, July 9, 1990, sec. C, p. 16.

Endnotes

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontents (New York: Norton, 1961), 49.

Robert A. Becker, Addicted to Misery (Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, Inc., 1989), 60.

Beverly DeAngelis, Secrets About Men Every Woman Should Know (New York: Delacorte Press, 1990), 156.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Dark Roots of American Optimism

by Barbara Ehrenreich

From Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America (Picador, 2009)

Click for PDF

Why did Americans, in such large numbers, adopt this uniquely sunny, self-gratifying view of the world? To some, the answer may be obvious: ours was the “new” world, overflowing with opportunity and potential wealth, at least once the indigenous people had been disposed of. Pessimism and gloom had no place, you might imagine, in a land that offered ample acreage to every settler squeezed out of overcrowded Europe. And surely the ever-advancing frontier, the apparently limitless space and natural resources, contributed to many Americans’ eventual adoption of positive thinking as a central part of their common ideology. But this is not how it all began: Americans did not invent positive thinking because their geography encouraged them to do so but because they had tried the opposite.

The Calvinism brought by white settlers to New England could be described as a system of socially imposed depression. Its God was “utterly lawless,” as literary scholar Ann Douglas has written, an all-powerful entity who “reveals his hatred of his creatures, not his love for them.”1 He maintained a heaven, but one with only limited seating, and those who would be privileged to enter it had been selected before their births through a process of predestination. The task for the living was to constantly examine “the loathsome abominations that lie in his bosom,” seeking to uproot the sinful thoughts that are a sure sign of damnation.2 Calvinism offered only one form of relief from this anxious work of self-examination, and that was another form of labor-clearing, planting, stitching, building up farms and businesses. Anything other than labor of either the industrious or spiritual sort—idleness or pleasure seeking—was a contemptible sin.

I had some exposure to this as a child, though in a diluted and nontheological form. One stream of my ancestors had fled Scotland when the landowners decided that their farms would be more profitably employed as sheep-grazing land, and they brought their harsh Calvinist Presbyterianism with them to British Columbia. Owing to a stint of extreme poverty in my grandmother’s generation, my great-grandparents ended up raising my mother, and although she rebelled against her Presbyterian heritage in many ways—smoking, drinking, and reading such ribald texts as the Kinsey reports on human sexuality—she preserved some of its lineaments in our home. Displays of emotion, including smiling, were denounced as “affected,” and tears were an invitation to slaps. Work was the only known antidote for psychic malaise, leaving my stay-at-home and only-high-school-educated mother to fill her time with fanatical cleaning and other domestic make-work. “When you’re down on your knees,” she liked to say, “scrub the floor.”

So I can appreciate some of the strengths instilled by the Calvinist spirit—or, more loosely, the Protestant ethic—such as the self-discipline and refusal to accept the imagined comfort of an unconditionally loving God. But I also know something of its torments, mitigated in my case by my more Irish-derived father: work—hard, productive, visible work in the world—was our only prayer and salvation, both as a path out of poverty and as a refuge from the terror of meaninglessness.

Elements of Calvinism, again without the theology, persisted and even flourished in American culture well into the late twentieth century and beyond. The middle and upper classes came to see busyness for its own sake as a mark of status in the 1980s and 1990s, which was convenient, because employers were demanding more and more of them, especially once new technologies ended the division between work and private life: the cell phone is always within reach; the laptop comes home every evening. “Multitasking” entered the vocabulary, along with the new problem of “workaholism.” While earlier elites had flaunted their leisure, the comfortable classes of our own time are eager to display evidence of their exhaustion—always “in the loop,” always available for a conference call, always ready to go “the extra mile.” In academia, where you might expect people to have more control over their workload hour by hour, the notion of overwork as virtue reaches almost religious dimensions. Professors boast of being “crazed” by their multiple responsibilities; summer break offers no vacation, only an opportunity for frantic research and writing. I once visited a successful academic couple in their Cape Cod summer home, where they proudly showed me how their living room had been divided into his-and-her work spaces. Deviations from their routine—work, lunch, work, afternoon run—provoked serious unease, as if they sensed that it would be all too easy to collapse into complete and sinful indolence.

In the American colonies—in New England and to a lesser degree Virginia—it was the Puritans who planted this tough-minded, punitive ideology. No doubt it helped them to survive in the New World, where subsistence required relentless effort, but they also struggled to survive Calvinism itself. For the individual believer, the weight of Calvinism, with its demand for perpetual effort and self-examination to the point of self-loathing, could be unbearable. It terrified children, like the seventeenth-century judge Samuel Sewall’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Betty. “A little after dinner,” he reported, “she burst out into an amazing cry, which caused all the family to cry too. Her mother asked the reason. She gave none; at last said she was afraid she would go to hell, her sins were not pardoned.”3 It made people sick. In England, the early seventeenth-century author Robert Burton blamed it for the epidemic of melancholy afflicting that nation:

The main matter which terrifies and torments most that are troubled in mind is the enormity of their offences, the intolerable burthen of their sins, God’s heavy wrath and displeasure so deeply apprehended that they account themselves … already damned … This furious curiosity, needless speculation, fruitless meditation about election, reprobation, free will, grace … torment still, and crucify the souls of too many.4

Two hundred years later, this form of “religious melancholy” was still rampant in New England, often reducing formerly healthy adults to a condition of morbid withdrawal, usually marked by physical maladies as well as inner terror. George Beecher, for example—brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe—tormented himself over his spiritual status until he “shattered” his nervous system and committed suicide in 1843.5

Certainly early America was not the only place to tremble in what Max Weber called the “frost” of Calvin’s Puritanism.6 But it may be that conditions in the New World intensified the grip of this hopeless, unforgiving religion. Looking west, the early settlers saw not the promise of abundance, only “a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men.”7 In the gloom of old-growth forests and surrounded by the indigenous “wild men,” the settlers must have felt as hemmed in as they had been in crowded England. And if Calvinism offered no individual reassurance, it at least exalted the group, the congregation. You might not be saved yourself, but you were part of a social entity set apart by its rigorous spiritual discipline—and set above all those who were unclean, untamed, and unchurched.

In the early nineteenth century, the clouds of Calvinist gloom were just beginning to break. Forests were yielding to roads and eventually railroads. The native peoples slunk westward or succumbed to European diseases. With the nation rapidly expanding, fortunes could be made overnight, or just as readily lost. In this tumultuous new age of possibility, people of all sorts began to reimagine the human condition and reject the punitive religion of their forebears. Religious historian Robert Orsi emphasizes the speculative ferment of nineteenth-century American religious culture, which was “creatively alive with multiple possibilities, contradictions, tensions, concerning the most fundamental questions (the nature of God, the meaning of Christ, salvation, redemption, and so on).”8 As Ralph Waldo Emerson challenged his countrymen: “Why should we grope among the dry bones of the past, or put the living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe? The sun shines to-day also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.”9

Not only philosophers were beginning to question their religious heritage. A substantial movement of workingmen, small farmers, and their wives used their meetings and publications to denounce “King-craft, Priest-craft, Lawyer-craft, and Doctor-craft” and insist on the primacy of individual judgment. One such person was Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, a self-educated watchmaker and inventor in Portland, Maine, who filled his journals with metaphysical ideas about what he called “the science of life and happiness”—the focus on happiness being itself an implicit reproach to Calvinism. At the same time, middle-class women were chafing against the guilt-ridden, patriarchal strictures of the old religion and beginning to posit a more loving, maternal deity. The most influential of these was Mary Baker, known to us today as Mary Baker Eddy—the daughter of a hardscrabble, fire-and-brimstone-preaching Calvinist farmer and, like Quimby, a self-taught amateur metaphysician. It was the meeting of Eddy and Quimby in the 1860s that launched the cultural phenomenon we now recognize as positive thinking.

As an intellectual tendency, this new, post-Calvinist way of thinking was called, generically enough, “New Thought” or the “New Thought movement.” It drew on many sources—the transcendentalism of Emerson, European mystical currents like Swedenborgianism, even a dash of Hinduism—and it seemed almost designed as a rebuke to the Calvinism many of its adherents had been terrified by as children. In the New Thought vision, God was no longer hostile or indifferent; he was a ubiquitous, all-powerful Spirit or Mind, and since “man” was really Spirit too, man was coterminous with God. There was only “One Mind,” infinite and all-encompassing, and inasmuch as humanity was a part of this universal mind, how could there be such a thing as sin? If it existed at all, it was an “error” as was disease, because if everything was Spirit or Mind or God, everything was actually perfect.

The trick, for humans, was to access the boundless power of Spirit and thus exercise control over the physical world. This thrilling possibility, constantly touted in today’s literature on the “law of attraction,” was anticipated by Emerson when he wrote that man “is learning the great secret, that he can reduce under his will, not only particular events, but great classes, nay the whole series of

events, and so conform all facts to his character.”10

New Thought might have remained in the realm of parlor talk and occasional lectures, except for one thing: the nineteenth century presented its adherents with a great practical test, which it passed with flying colors. In New Thought, illness was a disturbance in an otherwise perfect Mind and could be cured through Mind alone. Sadly, the strictly mental approach did not seem to work with the infectious diseases—such as diphtheria, scarlet fever, typhus, tuberculosis, and cholera—that ravaged America until the introduction of public sanitary measures at the end of the nineteenth century. But as Quimby and Eddy were to discover, it did work for the slow, nameless, debilitating illness that was reducing many middle-class Americans to invalidism.

The symptoms of this illness, which was to be labeled “neurasthenia” near the end of the century, were multitudinous and diffuse. According to one of her sisters, the teenage Mary Baker Eddy, for example, suffered from a “cankered” stomach and an “ulcer” on her lungs, “in addition to her former diseases.”11 Spinal problems, neuralgia, and dyspepsia also played a role in young Eddy’s invalidism, along with what one of her doctors described as “hysteria mingled with bad temper.”12 Most sufferers, like Eddy, reported back problems, digestive ills, exhaustion, headaches, insomnia, and melancholy. Even at the time, there were suspicions, as there are today in the case of chronic fatigue syndrome, that the illness was not “real,” that it was a calculated bid for attention and exemption from chores and social obligations. But we should recall that this was a time before analgesics, safe laxatives, or, of course, antidepressants, when the first prescription for any complaint, however counterproductively, was often prolonged bed rest.

Neurasthenia was hardly ever fatal, but to some observers it seemed every bit as destructive as the infectious diseases. Catharine Beecher, the sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe and poor George Beecher, traveled around the country and reported “a terrible decay of female health all over the land.” Her field notes include the following: “Milwaukee, Wis. Mrs. A. frequent sick headaches. Mrs. B. very feeble. Mrs. S., well, except chills. Mrs. D., subject to frequent headaches. Mrs. B. very poor health …. Do not know one healthy woman in the place.”13 Women were not the only victims. William James, who was to become the founder of American psychology, lapsed into invalidism as a young man, as did George M. Beard, who later, as a physician, coined the term “neurasthenia.” But the roster of well-known women who lost at least part of their lives to invalidism is impressive: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who memorialized her experience with cruelly ineffective medical treatments in “The Yellow Wallpaper”; Jane Addams, the founder of the first settlement house; Margaret Sanger, the birth control crusader; Ellen Richard, the founder of domestic science; and Alice James, sister of William and Henry James. Catharine Beecher herself, one of the chroniclers of the illness, “suffered from hysteria and occasional paralytic afflictions.”14

Without in any way impugning the motives of the afflicted, George M. Beard recognized that neurasthenias presented a very different order of problem from diseases like diphtheria, which, for the first time, were being traced to an external physical agent—microbes. Neurasthenia, as his term suggests, represented a malfunction of the nerves. To Beard, the ailment seemed to arise from the challenge of the new: some people simply could not cope with America’s fast-growing, increasingly urban, and highly mobile society. Their nerves were overstrained, he believed; they collapsed.

But the invalidism crippling America’s middle class had more to do with the grip of the old religion than the challenge of new circumstances. In some ways, the malady was simply a continuation of the “religious melancholy” Robert Burton had studied in England around the time when the Puritans set off for Plymouth. Many of the sufferers had been raised in the Calvinist tradition and bore its scars all their lives. Mary Baker Eddy’s father, for example, had once been so incensed to find some children playing with a semitame crow on the Sabbath that he killed the bird with a rock on the spot. As a girl, Eddy agonized over the Calvinist doctrine of predestination to the point of illness: “I was unwilling to be saved, if my brothers and sisters were to be numbered among those who were doomed to perpetual banishment from God. So perturbed was I by the thoughts aroused by this erroneous doctrine, that the family doctor was summoned, and pronounced me stricken with fever.”15

Similarly, Lyman Beecher, the father of Catharine and George, had urged them as young children to “agonize, agonize” over the condition of their souls and “regularly subjected their hearts to … scrutiny” for signs of sin or self-indulgence.16 Charles Beard, a sufferer himself and the son of a strict Calvinist preacher, later condemned religion for teaching children that “to be happy is to be doing wrong.”17 Even those not raised in the Calvinist religious tradition had usually endured child-raising methods predicated on the notion that children were savages in need of discipline and correction—an approach that was to linger in American middle-class culture until the arrival of Benjamin Spock and “permissive” child-raising in the 1940s.

But there is a more decisive reason to reject the notion that the invalidism of the nineteenth century arose from nervous exhaustion in the face of overly rapid expansion and change. If Beard’s hypothesis were true, you would expect the victims to be drawn primarily from the cutting edge of economic dynamism. Industrialists, bankers, prospectors in the Gold Rush of 1848 should have been swooning and taking to their beds. Instead, it was precisely the groups most excluded from the frenzy of nineteenth-century competitiveness that collapsed into invalidism—clergymen, for example. In this era—before megachurches and television ministries—they tended to lead somewhat cloistered and contemplative lives, often remaining within the same geographical area for a lifetime. And nineteenth-century clergymen were a notoriously sickly lot. Ann Douglas cites an 1826 report that “the health of a large number of clergymen has failed or is failing them”; they suffered from dyspepsia, consumption, and a “gradual wearing out of the constitution.”18

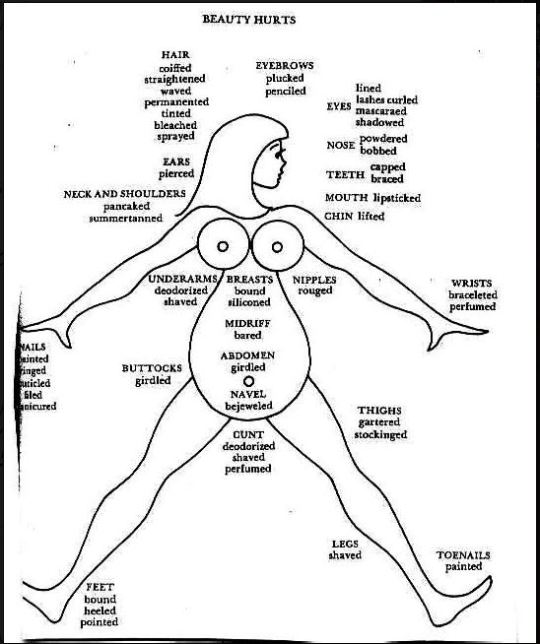

The largest demographic to suffer from invalidism or neurasthenia was middle-class women. Male prejudice barred them from higher education and most of the professions; industrialization was stripping away the productive tasks that had occupied women in the home, from sewing to soapmaking. For many women, invalidism became a kind of alternative career. Days spent reclining on chaise longues, attended by doctors and family members and devoted to trying new medicines and medical regimens, substituted for “masculine” striving in the world. Invalidism even became fashionable, as one of Mary Baker Eddy’s biographers writes: “Delicate ill-health, a frailty unsuited to labor, was coming to be considered attractive in the young lady of the 1930s and 1840s, and even in rural New Hampshire sharp young women like the Baker girls had enough access to the magazines and novels of their day to know the fashions.”19

Here, too, under the frills and sickly sentimentality of nineteenth-century feminine culture, we can discern the claw marks of Calvinism. The old religion had offered only one balm for the tormented soul, and that was hard labor in the material world. Take that away and you were left with the morbid introspection that was so conducive to dyspepsia, insomnia, backaches, and all the other symptoms of neurasthenia. Fashionable as it may have been, female invalidism grew out of enforced idleness and a sense of uselessness, and surely involved genuine suffering, mental as well as physical. Alice James rejoiced when, after decades of invalidism, she was diagnosed with breast cancer and told she would be dead in a few months.

Among men, neurasthenia sometimes arose in a period of idleness associated with youthful indecision about a career, as happened in the case of George Beard. Similarly, William James was uncertain about his early choice of medicine when, at the age of twenty-four, his back went out while he was bent over a cadaver. Already suffering from insomnia, digestive troubles, and eye problems, he fell into a paralyzing depression. The medical profession seemed to him too unscientific and illogical, but he could think of nothing else, writing, “I shall hate myself until I get some special work.”20 Women had no “special work”; a clergyman’s day-to-day labors were amorphous and overlapped with the kinds of things women normally did, like visiting the sick. Without real work—”special work”—the Calvinist or Calvinist-influenced soul consumed itself with self-loathing.

The mainstream medical profession had no effective help for the invalid, and a great many interventions that were actually harmful. Doctors were still treating a variety of symptoms by bleeding the patient, often with leeches, and one of their favorite remedies was the toxic, mercury-containing calomel, which could cause the jaw to rot away. In Philadelphia, one of America’s most noted physicians treated female invalids with soft, bland foods and weeks of bed rest in darkened rooms—no reading or conversation allowed. The prevailing “scientific” view was that invalidism was natural and perhaps inevitable in women, that the mere fact of being female was a kind of disease, requiring as much medical intervention as the poor invalid’s family could afford. Why men should also sometimes suffer was not clear, but they, too, were treated with bleedings, purges, and long periods of enforced rest.

Mainstream medicine’s failure to relieve the epidemic of invalidism, and the tragic consequences of many of its interventions, left the field open to alternative sorts of healers. Here is where Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, usually considered the founder of the New Thought movement and hence grandfather of today’s positive thinking, comes in. He had no use for the medical profession, considering it a source of more sickness than health. Having dabbled for some time in mesmerism—along with metaphysics and watchmaking—he went into practice as a healer himself in 1859. A fearless thinker, though by no means irreligious, he quickly identified Calvinism as the source of many of his patients’ ills. As he saw it, according to historian Roy M. Anker, “old-style Calvinism depressed people, its morality constricted their lives and bestowed on them large burdens of debilitating, disease-producing guilt.”21 Quimby gained a minor reputation with a kind of “talking cure,” through which he endeavored to convince his patients that the universe was fundamentally benevolent, that they were one with the “Mind” out of which it was constituted, and that they could leverage their own powers of mind to cure or “correct” their ills.

In 1863, Mary Baker Eddy, forty-two, made the then-arduous journey to Portland to seek help from Quimby, arriving so weak that she had to be carried up the stairs to his consulting rooms. 22 Eddy had been an invalid since childhood and might have been happy to continue that lifestyle—doing a little reading and writing in her more vigorous moments—if anyone had been willing to finance it. But her first husband had died and the second had absconded, leaving her nearly destitute in middle age, reduced to moving from one boardinghouse to another, sometimes just in time to avoid paying the rent. Perhaps she was a bit smitten with the handsome, genial Quimby, and possibly the feelings were returned; Mrs. Quimby certainly distrusted the somewhat pretentious and overly needy new patient. Whatever went on between them, Eddy soon declared herself cured, and when Quimby died three years later, she claimed his teachings as her own—although it should be acknowledged that Eddy’s followers still insist that she was the originator of the New Thought approach. Either way, Quimby proved that New Thought provided a practical therapeutic approach, which the prolific writer and charismatic teacher Mary Baker Eddy went on to promote.

Eddy eventually gained considerable wealth by founding her own religion—Christian Science, with its still ubiquitous “reading rooms.” The core of her teaching was that there is no material world, only Thought, Mind, Spirit, Goodness, Love, or, as she often put it in almost economic terms, “Supply.” Hence there could be no such things as illness or want, except as temporary delusions. Today, you can find the same mystical notion in the teachings of “coaches” like Sue Morter: the world is dissolved into Mind, Energy, and Vibrations, all of which are potentially subject to our conscious control. This is the “science” of Christian Science, much as “quantum physics” (or magnetism) is the “scientific” bedrock of positive thinking. But it arose in the nineteenth century as an actual religion, and in opposition to the Calvinist version of Christianity.

In the long run, however, the most influential convert to Quimby’s New Thought approach to healing was not Mary Baker Eddy but William James, the first American psychologist and definitely a man of science. James sought help for his miscellaneous ills from another disciple—and former patient—of Quimby’s, Annetta Dresser.23 Dresser must have been successful, because in his best-known work, The Varieties of Religious Experience, James enthused over the New Thought approach to healing: “The blind have been made to see, the halt to walk. Life-long invalids have had their health restored.”24 To James, it did not matter that New Thought was a philosophical muddle; it worked. He took it as a tribute to American pragmatism that Americans’ “only decidedly original contribution to the systematic philosophy of life”—New Thought—had established itself through “concrete therapeutics” rather than, say, philosophical arguments. New Thought had won its great practical victory. It had healed a disease—the disease of Calvinism, or, as James put it, the “morbidness” associated with “the old hell-fire theology.”25

James understood that New Thought offered much more than a new approach to healing; it was an entirely new way of seeing the world, so pervasive, he wrote, that “one catches [the] spirit at second-hand”:

One hears of the “Gospel of Relaxation,” of the “Don’t Worry Movement,” of people who repeat to themselves “Youth, health, vigor!” when dressing in the morning as their motto for the day. Complaints of the weather are getting to be forbidden in many households and more and more people are recognizing it to be bad form to speak of disagreeable sensations, or to make much of the ordinary inconveniences and ailments of life.26

As a scientist, he was repelled by much of the New Thought literature, finding it “so moonstruck with optimism and so vaguely expressed that an academically trained mind finds it almost impossible to read at all.” Still, he blessed the new way of thinking as “healthy-mindedness” and quoted another academic to the effect that it was “hardly conceivable” that so many intelligent people would be drawn to Christian Science and other schools of New Thought “if the whole thing were a delusion.”27

By the early twentieth century, the rise of scientific medicine, powered originally by the successes of the germ theory of disease, began to make New Thought forms of healing seem obsolete. Middle-class homemakers left their sickbeds to take up the challenge of fighting microbes within their homes, informed by Ellen Richards’s “domestic science.” Teddy Roosevelt, assuming the presidency in 1901, exemplified a new doctrine of muscular activism that precluded even the occasional nap. Of the various currents of New Thought, only Christian Science clung to the mind-over-body notion that all disease could be cured by “thought”; the results were often disastrous, as even some late-twentieth-century adherents chose to read and reread Mary Baker Eddy rather than take antibiotics or undergo surgery. More forward-looking advocates of New Thought turned away from health and found a fresh field as promoters of success and wealth. Not until the 1970s would America’s positive thinkers dare to reclaim physical illnesses—breast cancer, for example—as part of their jurisdiction.

However “moonstruck” its central beliefs, positive thinking came out of the nineteenth century with the scientific imprimatur of William James and the approval of “America’s favorite philosopher,” Ralph Waldo Emerson. Writing in the mid-twentieth century, Norman Vincent Peale, the man who popularized the phrase “positive thinking,” cited them repeatedly, though not as often as he did the Bible. James, in particular, made positive thinking respectable, not because he found it intellectually convincing but because of its undeniable success in “curing” the poor invalid victims of Calvinism. There is a satisfying irony here: in fostering widespread invalidism, Calvinism had crafted the instrument of its own destruction. It had handed New Thought, or what was to be called positive thinking, a dagger to plunge into its own chest.

But wait, there is a final twist to the story. If one of the best things you can say about positive thinking is that it articulated an alternative to Calvinism, one of the worst is that it ended up preserving some of Calvinism’s more toxic features—a harsh judgmentalism, echoing the old religion’s condemnation of sin and an insistence on the constant interior labor of self-examination. The American alternative to Calvinism was not to be hedonism or even just an emphasis on emotional spontaneity. To the positive thinker, emotions remain suspect and one’s inner life must be subjected to relentless monitoring.

In many important ways, Christian Science itself never fully broke with Calvinism at all. Its twentieth century adherents were overwhelmingly white, middle-class people of outstandingly temperate, even self-denying habits. The British writer V. S. Pritchett, whose father was a “Scientist,” wrote that they “gave up drink, tobacco, tea, coffee—dangerous drugs—they gave up sex, and wrecked their marriages on this account…It was notoriously a menopause religion.”28 In her later years, Mary Baker Eddy even brought back a version of the devil to explain why, in this perfect universe, things did not always go her way. Bad weather, lost objects, imperfect printings of her books—all these were attributed to “Malicious Animal Magnetism” emanating from her imagined enemies.

In my own family, the great-grandmother who raised my mother had switched from Presbyterianism to Christian Science at some point in her life, and the transition was apparently seamless enough for my grandmother to later eulogize her in a letter simply as “a good Christian woman.” My own mother had no more interest in Christian Science than she did in Presbyterianism, but she hewed to one of its harsher doctrines—that, if illness was not entirely imaginary, it was something that happened to people weaker and more suggestible than ourselves. Menstrual cramps and indigestion were the fantasies of idle women; only a fever or vomiting merited a day off from school. In other words, illness was a personal failure, even a kind of sin. I remember the great trepidation with which I confessed to my mother that I was having trouble seeing the blackboard in school; we were not the sort of people who needed glasses.

But the most striking continuity between the old religion and the new positive thinking lies in their common insistence on work—the constant internal work of self-monitoring. The Calvinist monitored his or her thoughts and feelings for signs of laxness, sin, and self-indulgence, while the positive thinker is ever on the lookout for “negative thoughts” charged with anxiety or doubt. As sociologist Micki McGee writes of the positive-thinking self-help literature, using language that harks back to its religious antecedents, “continuous and never-ending work on the self is offered not only as a road to success but also to a kind of secular salvation.”29 The self becomes an antagonist with which one wrestles endlessly, the Calvinist attacking it for sinful inclinations, the positive thinker for “negativity.” This antagonism is made clear in the common advice that you can overcome negative thoughts by putting a rubber band on your wrist: “Every time you have a negative thought stretch it out and let it snap. Pow. That hurts. It may even leave a welt if your rubber band is too thick. Take it easy, you aren’t trying to maim yourself, but you are trying to create a little bit of a pain avoidance reflex with the negative thoughts.”30

A curious self-alienation is required for this kind of effort: there is the self that must be worked on, and another self that does the work. Hence the ubiquitous “rules,” work sheets, self-evaluation forms, and exercises offered in the positive-thinking literature. These are the practical instructions for the work of conditioning or reprogramming that the self must accomplish on itself. In the twentieth century, when positive thinkers had largely abandoned health issues to the medical profession, the aim of all this work became wealth and success. The great positive-thinking text of the 1930s, Think and Grow Rich! by Napoleon Hill, set out the familiar New Thought metaphysics. “Thoughts are things”—in fact, they are things that attract their own realization. “ALL IMPULSES OF THOUGHT HAVE A TENDENCY TO CLOTHE THEMSELVES IN THEIR PHYSICAL EQUIVALENT.” Hill reassured his readers that the steps required to achieve this transformation of thoughts into reality would not amount to “hard labor,” but if any step was omitted, “you will fail!” Briefly put, the seeker of wealth had to draw up a statement including the exact sum of money he or she intended to gain and the date by which it should come, which statement was to be read “aloud, twice daily, once just before retiring at night and once after arising in the morning.” By strict adherence to this regimen, one could manipulate the “subconscious mind,” as Hill called the part of the self that required work, into a “white heat of DESIRE for money.” To further harness the subconscious mind to conscious greed, he advises at one point that one “READ THIS ENTIRE CHAPTER ALOUD ONCE EVERY NIGHT.”31

The book that introduced most twentieth-century Americans—as well as people worldwide—to the ceaseless work of positive thinking was, of course, Norman Vincent Peale’s 1952 The Power of Positive Thinking. Peale was a mainstream Protestant minister who had been attracted to New Thought early in his career, thanks, he later wrote, to a New thought Proponent named Ernest Holmes. “Only those who knew me as a boy,” he wrote, “can fully appreciate what Ernest Holmes did for me. Why, he made me a positive thinker.” sup>32 If Peale saw any conflict between positive thinking and the teachings of the Calvinist-derived Dutch Reformed Church that he eventually adopted as his denomination, it did not perturb him. A mediocre student, he had come out of divinity school with a deep aversion to theological debates—and determined to make Christianity “practical” in solving people’s ordinary financial, marital, and business problems. Like the nineteenth-century New Thought leaders before him, he saw himself in part as a healer; only the twentieth-century illness was not neurasthenia but what Peale identified as an “inferiority complex,” something he had struggled with in his own life. In one of his books, written well after the publication of his perennial best seller, The Power of Positive Thinking, he wrote:

A man told me he was having a lot of trouble with himself. “You are not the only one,” I reflected, thinking of the many letters I receive from people who ask for help with problems. And also thinking of myself; for I must admit that the person who has caused me the most trouble over the years has been Norman Vincent Peale …. If we are our own chief problem, the basic reason must be found in the type of thoughts which habitually occupy and direct our minds. 33

We have seen the enemy, in other words, and it is ourselves, or at least our thoughts. Fortunately though, thoughts can be monitored and corrected until, to paraphrase historian Donald Meyer’s summary of Peale, positive thoughts became “automatic” and the individual became fully “conditioned.”34 Today we might call this the work of “reprogramming,” and since individuals easily lapse back into negativity—as Peale often noted with dismay—it had to be done again and again. In The Power of Positive Thinking, Peale offered “ten simple, workable rules,” or exercises, beginning with:

Peale trusted the reader to come up with his or her own positive thoughts, but over time the preachers of positivity have found it more and more necessary to provide a kind of script in the form of “affirmations” or “declarations.” In Secrets of the Millionaire Mind, for example, T. Harv Eker offers the reader the following instructions in how to overcome any lingering resistance to the wealth he or she deserves:

Place your hand on your heart and say…

“I admire rich people!”

“I bless rich people!”

“I love rich people!”

“And I’m going to be one of those rich people too!”36

This work is never done. Setbacks can precipitate relapses into negativity, requiring what one contemporary guru, M. Scott Peck, calls “a continuing and never-ending process of self-monitoring.”37 Or, more positively, endless work may be necessitated by constantly raising your sights. If you are satisfied with your current condition, you need to “sharpen the saw,” in self-help writer Stephen Covey’s words, and admit you could be doing better. As the famed motivator Tony Robbins puts it: “When you set a goal, you’ve committed to CANI [Constant, Never-Ending Improvement]! You’ve acknowledged the need that all human beings have for constant, never-ending improvement. There is a power in the pressure of dissatisfaction, in the tension of temporary discomfort. This is the kind of pain you want in your life.”38

There is no more exhausting account of the self-work required for positive thinking than motivational speaker Jeffrey Gitomer’s story of how he achieved and maintains his positive attitude. We last encountered Gitomer demanding a purge of “negative people” from one’s associates, much as an old-style Calvinist might have demanded an expulsion of sinners, but Gitomer had not always been so self-confidently positive. In the early 1970s, his business was enjoying only “moderate success,” his marriage was “bad,” and his wife was pregnant with twins. Then he fell in with a marketing company called Dare to Be Great, whose founder now claims to have anticipated the 2006 best seller The Secret by thirty-five years. Told by his new colleagues that “you’re going to get a positive attitude … and you’re going to make big money. Go, go, go!” he sold his business and plunged into the work of self-improvement. He watched the motivational film Challenge to America over five times a week and obsessively reread Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich! with his new colleagues: “Each person was responsible for writing and presenting a book report on one chapter each day. There were 16 chapters in the book, 10 people in the room, and we did this for one year. You can do the math for how many times I have read the book.”39 At first the best he could do was fake a positive attitude: “Friends would ask me how I was doing, and I would extend my arms into the air and scream, ‘Great!’ Even though I was crappy.” Suddenly, “one day I woke up, and I had a positive attitude …. I GOT IT! I GOT IT!”40

Substitute the Bible for Think and Grow Rich! and you have a conversion tale every bit as dramatic as anything Christian lore has to offer. Like the hero of the great seventeenth-century Calvinist classic The Pilgrim’s Progress, Gitomer had found himself trapped by family and wallowing in his slough of despond—of mediocrity, rather than sin—and like Bunyan’s hero, Gitomer shook off his old business, and his first wife, in order to remake himself. Just as Calvinism demanded not only a brief experience of conversion but a lifetime of self-examination, Gitomer’s positive attitude requires constant “maintenance,” in the form of “reading something positive every morning, thinking positive thoughts every morning, … saying positive things every morning,” and so forth.41 This is work, and just to make that clear, Gitomer’s Little Gold Book of YES! Attitude offers a photograph of the author in a blue repairman’s shirt bearing the label “Positive Attitude Maintenance Department.”

Reciting affirmations, checking off work sheets, compulsively re-reading get-rich-quick books: these are not what Emerson had in mind when he urged his countrymen to shake off the shackles of Calvinism and embrace a bounteous world filled with “new lands, new men, and new thoughts.” He was something of a mystic, given to moments of transcendent illumination: “I become a universal eyeball. I am nothing; I see all…All mean egotism vanishes.”42 In such states, the self does not double into a worker and an object of work; it disappears. The universe cannot be “supply,” since such a perception requires a desiring, calculating ego, and as soon as ego enters into the picture, the sense of Oneness is shattered. Transcendent Oneness does not require self-examination, self-help, or self-work. It requires self-loss.

Still, surely it is better to obsess about one’s chances of success than about the likelihood of hell and damnation, to search one’s inner self for strengths rather than sins. The question is why one should be so inwardly preoccupied at all. Why not reach out to others in love and solidarity or peer into the natural world for some glimmer of understanding? Why retreat into anxious introspection when, as Emerson might have said, there is a vast world outside to explore? Why spend so much time working on oneself when there is so much real work to be done?

From the mid-twentieth century on, there was an all too practical answer: more and more people were employed in occupations that seemed to require positive thinking and all the work of self-improvement and maintenance that went into it. Norman Vincent Peale grasped this as well as anyone: the work of Americans, and especially of its ever-growing white-collar proletariat, is in no small part work that is performed on the self in order to make that self more acceptable and even likeable to employers, clients, coworkers, and potential customers. Positive thinking had ceased to be just a balm for the anxious or a cure for the psychosomatically distressed. It was beginning to be an obligation imposed on all American adults.

Notes

Ann Douglas, The Feminization of American Culture (New York: Avon, 1977), 145.

Thomas Hooker, quoted in Perry Miller, ed., The American Puritans: Their Prose and Poetry (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), 154.

Miller, American Puritans, 241.

Quoted in Noel L. Brann, “The Problem of Distinguishing Religious Guilt from Religious Melancholy in the English Renaissance,” Journal of the Rocky Mountain Medieval and Renaissance Association (1980): 70.

Julius H. Rubin, Religious Melancholy and Protestant Experience in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 161.

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Dover, 2003), 168.

William Bradford, quoted in Stephen Fender and Arnold Goldman, eds., American Literature in Context (New York: Routledge, 1983), 45.

Personal communication, Jan. 10, 2009.

Quoted in Catherine L. Albanese, A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 165.

Quoted in Albanese, Republic of Mind and Spirit, 167.

Quoted in Gillian Gill, Mary Baker Eddy (Cambridge: Perseus, 1998), 43.

Quoted in Caroline Fraser, God’s Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church (New York: Metropolitan, 1999), 34.

Quoted in Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts’ Advice to Women (New York: Anchor, 1989), 103.

Douglas, Feminization, 170.

Quoted in Anne Harrington, The Cure Within: A History of Mind-Body Medicine (New York: Norton, 2008), 112.

Douglas, Feminization, 170.

Barbara Sicherman, “The Paradox of Prudence: Mental Health in the Gilded Age,” Journal of American History 62 (1976): 880-912.

Quoted in Douglas, Feminization, 104.

Gill, Mary Baker Eddy, 33.

Quoted in Robert D. Richardson, William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 86.

Roy M. Anker, Self-Help and Popular Religion in Early American Culture: An Interpretive Guide (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999), 190.

Gill, Mary Baker Eddy, 128.

Richardson, William James, 275.

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 109.

Ibid., 104.

Ibid., 109.

Ibid., 109, 111n.

Quoted in Fraser, God’s Perfect Child, 195.

Micki McGee, Self-Help Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 142.

http:\\www.bripblap.com/2007/stopping-negative-thoughts/.

Napoleon Hill, Think and Grow Rich! (San Diego: Aventine Press, 2004), 52, 29, 71, 28, 30, 74.

Norman Vincent Peale, back cover quote on Fenwicke Holmes, Ernest Holmes: His Life and Times (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1970), http:\\self-improvement-ebooks.com/books/ehhlat.php.

Norman Vincent Peale, The Positive Principle Today (New York: Random House, 1994), 289.

Donald Meyer, The Positive Thinkers: Popular Religious Psychology from Mary Baker Eddy to Norman Vincent Peale and Ronald Reagan (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1998), 268.

Norman Vincent Peale, The Power of Positive Thinking (New York: Random House, 1994), 28.

T. Harv Eker, Secrets of the Millionaire Mind (New York: Harper Business, 2005), 94.

Quoted in McGee, Self-Help, Inc., 143.

Ibid., 142.

Jeffrey Gitomer, Little Gold Book, 164.

Ibid., 165.

Ibid., 169.

Quoted in Meyer, Positive Thinkers, 80.

0 notes

Text

Therapy and How it Undermines the Practice of Radical Feminism*

By Celia Kitzinger

(As published in Radically Speaking: Feminism Reclaimed, edited by Renate Klein and Diane Bell [Spinifex 1996])

*Excerpt from Celia Kitzinger (1993), Depoliticising the Personal: A Feminist Slogan in Feminist Therapy.

One of the great insights of second wave feminisms was the recognition that “the personal is political” — a phrase first coined by Carol Hanisch in 1971. We meant by this that all our small, personal, day-to-day activities had political meaning, whether intended or not. Aspects of our lives that had previously been seen as purely “personal” — housework, sex, relationships with sons and fathers, mothers, sisters and lovers — were shaped by, and influential upon, their broader social context. “The slogan meant, for example, that when a woman is forced to have sex with her husband it is a political act because it reflects the power dynamics in the relationship: wives are property to which husbands have full access” (Rowland: 1984, p. 5). A feminist understanding of “politics” meant challenging the male definition of the political as something external (to do with governments, laws, banner-waving, and protest marches) towards an understanding of politics as central to our very beings, affecting our thoughts, emotions, and the apparently trivial everyday choices we make about how we live. Feminism meant treating what had been perceived as merely “personal” issues as political concerns.

This article explores the way in which the slogan, “the personal is political” is used within feminist psychological writing, with particular reference to therapy. The growth in feminist therapies (including self-help books, co-counselling, twelve-step groups, and so on, as well as one-to-one therapy) has been rapid, and has attracted criticism from many feminists concerned about their political implications (Cardea: 1985; Hoagland: 1988; Tallen: 1990a and b; Perkins: 1991). However, many feminist psychologists (both researchers and practitioners) state explicitly their belief that “the personal is political.”

According to some, this principle has “prevailed as a cornerstone of feminist therapy” (Gilbert: 1980), and qualitative methodologies have often been adopted by feminists precisely because they permit access to “personal” experience, the “political” implications of which can be drawn out through the research. It would be unusual to find a feminist psychologist who denied believing that “the personal is political,” despite the existence of feminist critiques of some of its implications (its false universalizing of women’s experience, for example, see hooks 1984, and the — ironic — tendency of some women to perceive the slogan’s categories of “personal” and “political” as polarised and in competition, see David: 1992). However, widespread concurrence with this slogan amongst feminist psychologists conceals a variety of interpretations. This article illustrates four of those differing psychological interpretations of “the personal is political,” and argues that far from politicising the personal, psychology personalises the political, focuses attention on “the revolution within,” concentrates on “validating women’s experience” at the expense of political analysis of that experience, and seeks to “empower” women, rather than accord real political power.

Two caveats before launching into my main argument.

First, this article does not claim to present a thorough overview of the whole of feminist psychology — a huge and growing area. Moreover, unlike other critiques (e.g. Jackson: 1983; Sternhall: 1992; Tallen: 1990a and b), this article is not an attack on any one particular brand of psychology, or a discussion from within the discipline (e.g. Burack: 1992). Rather, its aim is to stand outside the disciplinary framework of psychology and to draw attention to the political problems inherent in the very concept of “feminist psychology” per se.

Second, “it doesn’t seem fair,” said one referee, “to scoff at institutions that help women live their lives in less pain.” Many women have been helped by therapy. I have heard enough women say “it saved my life” to feel almost guilty about challenging psychology. Many women say that it was only with the help of therapy that they became able to leave an abusive relationship, to rid themselves of incapacitating fears and anxieties, or to stop drug abuse. Anything that saves women’s lives, anything that makes women happier, most be feminist — mustn’t it? Well, no. It’s possible to patch women up and enable them to make changes in their lives without ever addressing the underlying political issues that cause these personal problems in the first place. “I used to bitch at my husband to do housework and nothing happened,” a woman from Minnesota told Harriet Lerner (1990, p. 15); “Now I’m in an intensive treatment program for codependency and I’m asserting myself very strongly. My husband is more helpful because he knows I’m co-dependent and he supports my recovery.” For this woman, the psychological explanation (“I’m codependent and need to recover”) was more successful than the feminist explanation (women’s work as unpaid domestic labor for men, Mainardi: 1970) in creating change. With the idea of herself as sick, she was able to make him do housework. As Carol Tavris (1992) says, “Women get much more sympathy and support when they define their problems in medical or psychological than in political terms.” The codependency explanation masks what feminists see as the real cause of our problems — male supremacy. Instead we are told that the cause lies in our own “codependency.” This is not feminism. Although it’s clear that “many women have been helped by therapy,” it is equally clear that many women have been helped, and feel better about themselves, as a result of (for example) dieting, buying new clothes, or joining a religious cult. Historically, as Bette Tallen (1990a, p. 390) points out, women have “sought refuge in such institutions as the Catholic church or the military. But does this mean that these are institutions that should be fully embraced by feminists?” The reasons behind the rush into psychology, and the benefits it offers (as well as the price it exacts) are discussed in more detail elsewhere (Kitzinger and Perkins: 1993). In this article, I focus more narrowly on psychological interpretations of “the personal is political,” and the implications of these for feminism.

Personalizing the Political

In this interpretation of “the personal is political,” instead of politicising the “personal,” the “political” is personalised. Political concerns, national and international politics, and major social, economic, and ecological disasters are reduced to personal, individual psychological matters.

This wholesale translation of the political into the personal is characteristic, not just of feminist psychology, but of psychology generally. In the USA a group of twenty-two professionals spent three years and $73,500 in coming to the conclusion that lack of self-esteem is the root cause of “many of the major social ills that plague us today” (The Guardian: April 13, 1990). Sexual violence against women is addressed by setting up social skills training and anger management sessions for rapists (now available in sixty jails in England and Wales, The Guardian: May 21, 1991), and racism becomes something to get off your chest in a counselling workshop (Green: 1987). Many people now think of major social and political issues in psychological terms.

In fact, the whole of life can be seen as one great psychological exercise. Back in 1998, Judi Chamberlain pointed out that mental hospitals tend to use the term “therapy” to describe absolutely everything that goes on inside them:

…making the beds and sweeping the floor can be called “industrial therapy,” going to a dance or movie “recreational therapy,” stupefying patients with drugs “chemotherapy,” and so forth. Custodial mental hospitals, which offer very little treatment, frequently make reference to “milieu therapy,” as if the very hospital air were somehow curative (1977, p. 131).

A decade or so later, with psychology’s major clientele not in mental hospitals but in the community, everything in our lives is translated into “therapy.” Reading books becomes “bibliotherapy;” writing (Wenz: 198), journal keeping (Hagan: 1988), and art are all ascribed therapeutic functions. Even taking photographs is now a psychological technique. Feminist “phototherapist” Jo Spence drew on the psychoanalytic theories of Alice Miller (1987) and advocates healing (among other “wounds”) “the wound of class shame” through photography. And although reading, writing, and taking photographs are ordinary activities, in their therapeutic manifestation they require expert guidance: “I don’t think people can do this with friends or by themselves…they’ll never have the safety working alone that they’ll get working with a therapist because they will encounter their own blockages and be unable to get past them” (Spence: 1990, p. 39). While not wishing to deny that reading, writing, art, photography, and so on might make some people feel better about themselves, it is disturbing to find such activities assessed in purely psychological terms. As feminists, we used to read in order to learn more about feminist history and culture; write and paint to communicate with others. These were social activities directed outwards; now they are treated as explorations of the self. The success of what we do is evaluated in terms of how it makes us feel. Social conditions are assessed in terms of how the inner life of individuals responds to them. Political and ethical commitments are judged by the degree to which they enhance or detract from our individual sense of well being.

Feminist therapists now “prescribe” political activities for their clients — not for their inherent political value, but as cure-alls. The “Guidelines for Feminist Therapy” offered by therapist Marylou Butler in the Handbook of Feminist Therapy (1985) includes the suggestion that feminist therapists should make referrals to women’s centres, CR groups, and feminist organisations, when that would be therapeutic for clients” (p. 37). Consciousness Raising — the practice of making the personal political — was never intended to be “therapy” (Sarachild: 1978). Women who participate in feminist activism with the goal of feeling better about themselves are likely to be disappointed. In sending women to feminist groups, the primary aims of which are activist rather than therapeutic, therapists are doing a disservice to both their clients and to feminism.

Our relationships, too, are considered not in terms of their political implications, but rather, in terms of their therapeutic functions. Therapy used to name what happened between a therapist and a client. Now, as Bonnie Mann points out, it accurately describes what happens between many women in daily interactions: “any activity organised by women is boxed into a therapeutic framework. Its value is determined on the basis of whether or not it is ‘healing’:”

I have often seen an honest conversation turn into a therapeutic interaction before my eyes. For instance, I mention something that has bothered, hurt, or been difficult for me in some way. Something shifts. I see the woman I am with take on The Role of the Supportive Friend. It is as if a tape clicks into her brain, her voice changes, I can see her begin to see me differently, as a victim. She begins to recite the lines, “That must have been very difficult for you,” or “That must have felt so invalidating,” or “What do you think you need to feel better about that?” I know very well the corresponding tape that is supposed to click into my own brain: “I think I just needed to let you know what was going on for me,” or “It helps to hear you say that, it feels very validating,” or “I guess I just need to go off alone and nurture myself a little” (1987, p. 47).

Psychological ways of thinking have spilled out of the therapists office, the AA groups, and self-help books, the experiential workshops and rebirthing sessions to invade all aspects of our lives. The political has been thoroughly personalised.

Revolution from Within

Another common feminist psychologising of “the personal is political” goes something like this:

The supposedly “personal activity of therapy is deeply political because learning to feel better about ourselves, raising our self-esteem, accepting our sexualities and coming to terms with who we really are — all these are political acts in a heteropatriarchal world. With woman-hating all around us, it is revolutionary to love ourselves, to heal the wounds of patriarchy, and to overcome self-oppression. If everyone loved and accepted themselves, so that women (and men) no longer projected on to each other their own repressed self-hatreds, we would have real social change.

This is a very common argument, most recently rehearsed in Gloria Steinem’s Revolution from Within. As Carol Sternhall points out in a critical review, “The point of all this trendy, tied-dyed [sic] shrinkery isn’t simply feeling better about yourself — or rather, it is, because feeling better about all our selves is now the key to worldwide revolution” (1992, p. 5).

In this model, the “self” is naturally good, but has to be uncovered from beneath the layers of internalised oppression and healed from the wounds inflicted on it by a heteropatriarchal society. Despite her manifest differences from Gloria Steinem in other areas, lesbian feminist therapist Laura Brown (1992) shares Steinem’s notion of the “true self.” She writes, for example, of a client’s “struggle to recover her self from the snares of patriarchy” (pp. 241-42), by “peel(ing) away the layers of patriarchal training” (p. 242) and “heal(ing) the wounds of childhood” (p. 245); in therapy with Laura Brown, a woman is helped to “know herself” (p. 246), to move beyond her “accommodated self” (p. 243) and discover her “true self” (p. 243) (or “shammed [sic] inner self” p. 245) and live “at harmony with herself” (p. 243). In most feminist psychology, this inner self is characterised as a beautiful, spontaneous little girl. Getting in touch with and nurturing her is a first step in creating social change. It is “revolution from within.”

This set of ideas has its roots in the “growth movement” of the 1960s, which emphasised personal liberation and “human potential.” Back then, the central image was of a vaguely defined “sick society.”

“The System” was poisoned by its materialism, consumerism, and lack of concern for the individual. These things were internalised by people; but underneath the layers of “shit” in each person lay an essential “natural self” which could be reached through various therapeutic techniques. What this suggests is that revolutionary change is not something that has to be built, created or invented with other people, but that it is somehow natural, dormant in each of us individually and only has to be released (Scott and Payne: 1984, p. 22).

The absurdity of taking this “revolution from within” argument to its logical conclusion is illustrated by one project, the offspring of a popular therapeutic program, which proposed to end starvation. Not, as might seem sensible, by organising soup kitchens, distributing food parcels to the hungry, campaigning for impoverished countries to be released from their national debts, or sponsoring farming cooperatives. Instead, it offers the simple expedient of getting individuals to sign cards saying that they are “willing to be responsible for making the end of starvation an idea whose time has come.” When an undisclosed number of people have signed such cards, a “context” will have been created in which hunger will somehow end (cited in Zilbergeld: 1983, pp. 5-6). Of course, Laura Brown, along with many other feminist therapists, would probably also want to challenge the obscenity of this project. Yet the logic of her own arguments permits precisely this kind of interpretation.

Such approaches are a very long way from my own understanding of “the personal is political.” I don’t think social change happens from the inside out. I don’t think people have inner children somewhere inside waiting to be nurtured, reparented, and their natural goodness released into the world. On the contrary, as I have argued elsewhere (Kitzinger: 1987; Kitzinger and Perkins: 1993), our inner selves are constructed by the social and political contexts in which we live, and if we want to alter people’s behavior it is far more effective to change the environment than to psychologise individuals. Yet as Sarah Scott and Tracey Payne (1984, p. 24) point out, “when it comes to doing therapy it is essential to each and every technique that women see their ‘real’ selves and their ‘social’ selves as distinct.” This means that the process of making ethical and political decisions about our lives is reduced to the supposed ‘discovery’ of our true selves, the honouring of our “hearts desires.” Political understandings of our thoughts and feelings is occluded, and our ethical choices are cast within a therapeutic rather than a political framework. A set of repressive social conditions has made life hard for women and lesbians. Yet the “revolution from within” solution is to improve the individuals, rather than change the conditions.

Psychology suggests that only after healing yourself can you begin to heal the world. I disagree. People do not have to be perfectly functioning, self-actualised human beings in order to create social change. Think of the feminists you know who have been influential in the world, and who have worked hard and effectively for social justice: Have they all loved and accepted themselves? The vast majority of those admired for their political work go on struggling for change not because they have achieved self-fulfilment (nor in order to attain it), but because of their ethical and political commitments, and often in spite of their own fears, self-doubts, personal angst, and self-hatreds. Those who work for “revolution without” are often no more “in touch with their real selves” than those fixated on inner change: this observation should not be used (as it sometimes is) to discredit their activism, but rather to demonstrate that political action is an option for all of us, whatever our state of psychological well-being. Wait until your inner world is sorted out before shifting your attention to the outer, and you are, indeed “waiting for the revolution” (Brown: 1992).