Text

Ki Tissa: A Lesson in Leadership

Moses was on top of Mount Sinai, experiencing Divine revelation on a level beyond the grasp of ordinary prophets.

At the foot of the mountain, however, the people began to worry. Not knowing why Moses was taking so long, not understanding how he could live without food and water for forty days, they felt abandoned and leaderless. They demanded that Aaron make them a golden calf, and they worshipped it.

God’s response was immediate — He banished Moses from Mount Sinai:

“Leave! Go down! The people whom you brought out of Egypt have become corrupt.” (Exodus 32:7)

It seems unfair. The people sin, and Moses is kicked off the mountain?

A Suitable Leader

In order for a leader to succeed, he must be appreciated and valued by his followers. The leader may possess a soul greatly elevated above the people, but it is crucial that the people should be able to relate to and learn from their leader.

At Mount Sinai, the Jewish people were on a lofty spiritual level. As a result, Moses was able to attain a supreme level of prophecy and revelation on top of the mountain. But after they sinned with the golden calf, Moses would no longer be a suitable leader were he to retain his spiritual attainments. It was necessary for Moses to “step down,” to lower himself, in order to continue serving as their guide and leader.

This idea is clearly expressed by the Talmud in Berachot 32a:

“What does it mean, ‘Go down’? God told Moses, ‘Go down from your greatness. I only gave you pre-eminence for the sake of the Jewish people. Now they have sinned — why should you be elevated?’

Immediately, Moses’ [spiritual] strength left him.”

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 160-161. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. I, pp. 142-143.)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

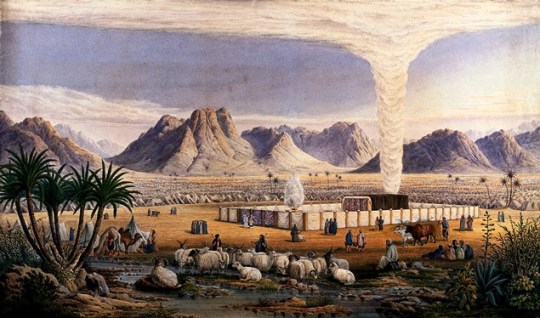

Terumah: Betzalel's Wisdom

The Torah reading of Terumah begins the section dealing with building the Mishkan (Tabernacle) and making the priestly clothes. These chapters are among the few in which the Torah places great emphasis on external beauty — art, craftsmanship, and aesthetics.

Of particular interest is the protagonist of this unique construction: the master craftsman, Betzalel. The Midrash weaves many stories about Betzalel’s wisdom and skill. In particular, the Sages noted the significance of his name, which means, “in God’s shadow”:

Betzalel was certainly sharp to be able to reconstruct the original divine message. Why did Moses change the order that God had told him?

The Scholar and the Artist

One way in which we can distinguish between the scribbles of a five-year-old and a masterpiece by Rembrandt is the degree to which the work of art reflects reality. A true artist is acutely sensitive to the finest details of nature. He must be an expert in shading, color, texture, and composition. A great artist will be disturbed by the smallest deviations, just as a great musician is perturbed by a note that is not exactly right in pitch, length, and emphasis.

There is a difference between the natural order of the world as perceived through the trained eye of an artist, and the proper order as understood through the wisdom of a scholar. The artist always compares the subject at hand to reality. The scholar, on the other hand, organizes topics according to their ethical and spiritual significance.

When Moses heard God command that Betzalel build the “tabernacle, ark, and vessels,” he did not know whether the order was significant. Since the tabernacle was in effect just the outer building containing the ark and the other vessels, Moses knew that the ark and vessels were holier. Therefore, when relaying the command to Betzalel, he mentioned them in order of importance, starting with the most sacred.

Why then did God put the tabernacle first? Moses decided that the original command started with the general description — the Tabernacle, the overall goal — and then continued with the details, the ark and vessels.

Betzalel, an artist with a finely tuned sensitivity to physical reality, noticed the slight discrepancy in Moses’ description. He realized that the word tabernacle did not refer to the overall construction, but to the outer building. As such, it should have come first, just as in the building of any home. The order was not from the general to the detailed, nor from the less holy to the holier, but from the outside to the inside.

Moses then comprehended the significance of Betzalel’s name, “in God’s shade.” Why shade? Wisdom may be compared to light, while artistic talent is like shade. Light is certainly greater and brighter then shade; but if we want to perceive an object completely, we need to see all of its aspects, both light and shade. In order that the Tabernacle could achieve its purpose, it required the special artistic insight of Betzalel.

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 144-146. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. II, p. 262.)

0 notes

Text

Said Rabbi Ishmael:

MeTat, head of the angels, told me (Rabbi Ishmael): out of [the] love that G-d loved me [with] more than any [other] angel in heaven, He made me pride-clothing (sic) in which all kinds of glories are fixed, and dressed me and made me a coat in which all kinds of brightness and splendor are fixed, and raised me and made me a kingdom-crown in which 49 gemstones are fixed and their light is like the sun, and their brightness spreads in four heaven-plain’s winds and in seven heavens and in four winds, and tied it to my head and called me ‘lesser HaShem’ ” in front of all the entourage-of-heaven, as it says (Exodus, 23,21):” … for My Name is in him.

Said Rabbi Ishmael: MeTat, head of the angels, told me: splendor in all heaven, since G-d took me to serve the honor-chair and the carriage’s (Merkava) wheels and all of the Divine spirit’s guarantors, [and] promptly my flesh turned into a fire-flame and my tendons [turned] into burning hot fire, and my bones into broom-ember, and my eyelids into sparkles, and my eye-wheels into fire-torches, and my head-hair into flame-blazes, and all my organs into burning fire-wings, and all my body-height into a blazing fire, to my right, hewers of fire-flames, and to my left, torches-burners, and my surroundings are floating in a tempest-wind and a storm and a voice of noise in noise in front of and behind me.

Up to here we wrote a few Braitas (Aramaic, external Mishna) of Merkavah.

Know that MeTat is called as mitetor, which is a leader, as in Bereshit Rabba (see, Albeck, section 5, starting “let the water under heaven gather together onto one place”), let the water gather, G-d became a mitetor to the water, meaning a leader, hence the name MeTat means leader of the world and singing song (Hebrew: ron) everyday, and of him it was said (Exodus, 23, 21): “Beware of him and obey his voice, provoke him not… for My Namw is in him”. Shad’ai (literally, guard of Israel’s doors) in MeTat (equal in gematria), and more My Name is in him, replace the [Letter] Kof of is engraved in his heart for my (G-d’s) name is in him. And the voice hits and exhausting his power, in the place where the name is engraved and from there hear the ministering angels, and from there it explodes, “Is not my word like as fire?... and like a hammer that breaketh the rock in pieces?” (Jeremiah, 23, 29) to that it was said (Exodus, 23, 21): “Beware of him and obey his voice, provoke him not… for My Name is in him.” That is (Ibid. 22) “But if thou shalt indeed obey his voice, and do all that I speak” and it is written (Ezekiel, 1, 28) “… and I heard a voice of one that spoke.” In Rabbi Akiva’s alphabet, 70 names has he, MeTat, and [also] the Name “lesser HaShem,” as he that will walk among us, and it did not say you will walk [among us], but he will walk and he stands as it is written (Kings A, 22, 19): “… I saw the Lord sitting on his throne, and all the host of heaven standing by him on his right-hand and on his left.” But where it is written that he is sitting it is only a semblance of sitting, he looks as-if he is sitting, since he is the judge of them all.”

~ (ibid)

— The Ways of Metatron - A Book of Enoch by Eleazar of Worms

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yitro: Serving the Community

“Moses sat to judge the people. They stood around Moses from morning to evening.” (Exod. 18:13)

From the account in the Torah, it would seem that Moses spent all his time judging the people. Yet it was clear to the Sages that this could not be the case.

Overworked Judges

The Talmud (Shabbat 10a) relates that two dedicated judges worked such long hours that they were overcome with fatigue. (It is unclear whether this was a physical weakness from overwork, or a psychological depression from time lost from Torah study.) When Rabbi Hiyya saw their exhaustion, he advised the two scholars to limit their hours in court:

Rav Hiyya’s statement requires clarification. If judging is such a wonderful occupation — one becomes a partner with God! — then why not adjudicate all day long? And in what way is the work of a judge like creating the world?

Personal Well-Being vs. Public Service

Great individuals aspire to serve the community and help others to the best of their abilities. The two judges felt that they could best serve their community by bringing social justice and order through the framework of the judicial system. Therefore, they invested all of their time and energy in judging the people. For these scholars, any other activity would be a lesser form of divine service. However, their dedication to public service was so intense that it came at the expense of their own personal welfare, both physical and spiritual.

Rabbi Chiyya explained to the scholars that while their public service was truly a wonderful thing, it is not necessary to neglect all other aspects of life. If one only judges for a single hour, and spends the rest of his time improving his physical and spiritual well-being so that he can better serve in his public position, then his entire life is still directed towards his true goal. It is clear that personal growth will enhance one’s community service. Better an hour of productive activity in a fresh, relaxed state of mind and body, than many hours of constant toil in a tired and frenzied state.

Two Parts of the Day

What is the connection between Moses’ judging “from morning to evening” and the description of the first day of Creation, “It was evening and morning, one day”? The day is one unit, made up of two parts — daytime and night. The daytime is meant for activity and pursuing our goals, while the night is the time for rest and renewal. Together, daytime and night form a single unit, constituting a “day.”

The balance of these two aspects — activity and renewal — is particularly appropriate for those who labor for the public good. The hours that we devote to physical and spiritual renewal help us in our public roles; they become an integral part of our higher aspiration to serve the community.

Gold from the Land of Israel pp. 130-132. Adapted from Ein Eyah vol. III, pp. 4-5. Illustration image: King Solomon (Gustave Dore, 1866)

0 notes

Text

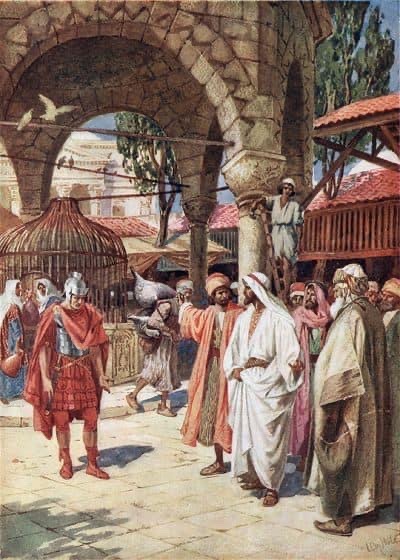

R’ Pinchas bar Chama remarked: “Whoever has a sick person at home should go to a sage and ask him to pray” (Bava Basra 116a)

Similarly, the Talmud states that for every physical and spiritual affliction (may they never come upon us), the Jewish people would approach the sage and tzadik of the generation to beseech him to pray and arouse mercy for them. See there, and you will find many awesome stories about the greatness of the power and prayers of the tzadikim. (See Taanit 3).

Elsewhere in the Talmud, it states: “R’ Chanina ben Dosa used to pray for the sick.” When Rabban Gamliel’s son became ill, he sent two Torah scholars to R’ Chanina to ask him to pray for Divine Mercy on his son’s behalf. R’ Yochanan ben Zakkai did similarly when his own son became ill, saying to R’ Chanina, “Chanina, my son, beseech mercy for my child.” (Berachot 34b)

Tales of the holy Hasid and a Roman G-d-fearer.

“When he (Yeshua) had entered Capernaum, a centurion came forward to him, appealing to him, “master, my servant is lying paralyzed at home, suffering terribly.” And he said to him, “I will come and heal him.” But the centurion replied, “Master, I am not worthy to have you come under my roof, but only say the word, and my servant will be healed. For I too am a man under authority, with soldiers under me. And I say to one, ‘Go,’ and he goes, and to another, ‘Come,’ and he comes, and to my servant, ‘Do this,’ and he does it.” When Yeshua heard this, he marveled and said to those who followed him, “Truly, I tell you, with no one in Israeld have I found such faith. And to the centurion Yeshua said, “Go; let it be done for you as you have believed.” And the servant was healed at that very moment.” ~ (Mattai. 8 )

B”H

0 notes

Text

Beshalach: Preparing for Sinai: The Mitzvot of Marah

Even before the Torah was revealed at Mount Sinai, the Jewish people received several mitzvot at a place called Marah:

“They came to Marah... there God taught them a decree and a law, and there He tested them.” (Exod. 16:23-25)

According to Sanhedrin 56b, one of the mitzvot that God taught at Marah was the mitzvah of Shabbat. It appears that Marah was a prelude of sorts for receiving the Torah at Sinai. How did the mitzvah of Shabbat prepare them for the Sinaitic revelation? And in what way was Marah a “test” for the Jewish people?

Preparing to Receive the Torah

The area was called Marah because the waters there were bitter (mar).

“When Moses cried out to God, He showed him a certain tree. Moses threw it in the water, and the water became sweet” (Exod. 15:25).

When a person is ill, that which is sweet may taste bitter. Such was the case with the waters of Marah, which appeared to be bitter, but were in fact sweet. This is a metaphor for the Torah itself — its laws are sweet to those with a pure soul and a refined character, yet bitter and burdensome to those with a coarser nature (Maimonides, Hilchot De'ot 2:1).

Marah laid the groundwork for Sinai by reinforcing the traits of kindness and compassion that characterize the Jewish people (Yevamot 79a). The people would then be ready to receive the Torah, as their moral state would allow them to appreciate the sweetness of the Torah’s laws.

How did the mitzvah of Shabbat accomplish this?

Even though the Sabbath commemorates the creation of the universe, it was not given to all of humanity. Shabbat is a special gift for the Jewish people (Sanhedrin 58b). Why is that?

The Test of Marah

To bolster social order and cohesion, it is important that people are actively engaged in working for their livelihood. Work and business interactions help build relationships and trust between individuals and groups. Even if two people would not ordinarily be inclined to like one another, work can provide a platform for them to bridge any divides, as it is in their mutual interest to collaborate.

If people are not working together, however, these incentives are no longer present. It is human nature to prioritize one’s own interests. Without an impetus to gain the good will of others, people tend to revert to self-centered tendencies.1

This was the test of Marah. The Jewish people were given the Sabbath day of rest — would they discover within themselves an innate quality of compassion? Would they remain considerate and accommodating to one another, despite the lack of material benefit to be gained from kindness on the day of rest?

The seven mitzvot of the Noahide Code, which are binding upon all of humanity, do not demand the refinement of human nature. They only require the avoidance of evil. The Torah, however, was given to the Jewish people in order to elevate them to be a holy people. The ethical ideals of Israel cannot be based on expediency and personal gain, but on a love for “that which is good and proper in the eyes of God” (Deut. 12:28). Therefore, it was necessary to bolster the foundations for their innate goodness. In this way, the mitzvot of Marah paved the way for the Torah’s revelation at Sinai.

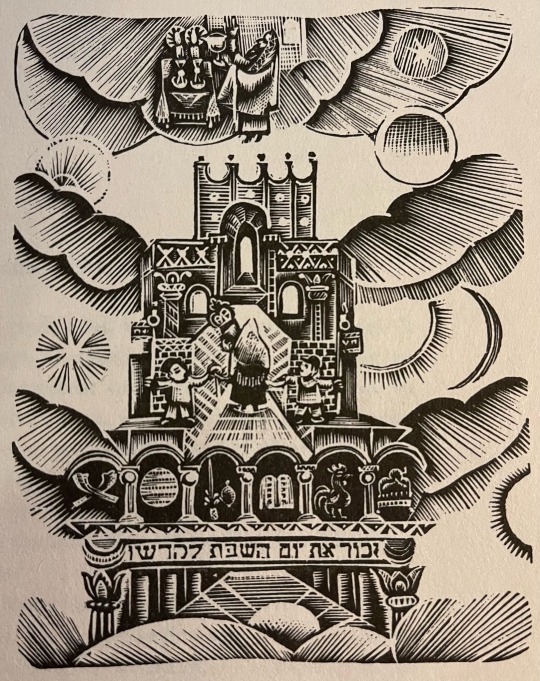

Adapted from Otzarot HaRe’iyah vol. II, pp. 172-173) Illustration image: The Sabbath Rest (Samuel Hirszenberg, 1894)

1 We have seen how social distancing measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic have caused "major problems in the economic, social, political and psychological spheres... The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has caused widespread unrest in society and unprecedented changes in lifestyle, work and social interactions, and increasing social distance has severely affected human relations.” ('Social Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Systematic Review.’ Invest Educ Enferm. 2022)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Va'eira: "Who Brings You Forth"

HaMotzi — the Blessing for Bread

As a rule, most of the blessings recited over food speak of God as the Creator. For example, we say: בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָעֵץ (“Creator of fruits of the tree”), בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה (“Creator of fruits of the ground”), בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הַגָּפֶן (“Creator of fruits of the vine”).

But the blessing for bread does not fit this pattern. Before eating bread, we say HaMotzi — הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ — “Who brings forth bread from the earth.” Why don’t we acknowledge God as “the Creator of bread,” following the formulation of other blessings?

It is highly significant that the wording of the blessing of HaMotzi mirrors the language used by God in His announcement to Moses:

Is there some connection between bread and the Exodus from Egypt?

The Special Role of Bread

The Earth contains an abundance of nutrients and elements, and through various processes, both natural and man-made, these elements are transformed into sustenance suitable for human consumption. However, when it comes to foods that are not essential to human life, it is difficult to know whether the nutrients and elements have attained their ultimate purpose upon becoming food. In fact, their utility began while they were still in the ground, and we cannot confidently state that they are now, in the form of a fruit or vegetable, more vital to the world’s functioning.

Bread, on the other hand, is the staff of life. Bread is necessary for our physical and mental development. As the Talmud states, “A child does not know how to call ‘Father’ and ‘Mother’ until he tastes grain” (Berachot 40b). This emphasizes the importance of bread in sustaining life, setting it apart from other foods. The elements used to make bread have attained a significant role that they lacked when they were still buried inside the earth.

The words of HaMotzi blessing — “Who brings forth bread from the earth” — reflect this aspect of bread. The act of “bringing out” draws our attention to two stages: the elements’ preliminary state in the ground, and their final state as bread, suitable for sustaining humanity. Other blessings focus on the original creation of fruits and vegetables. HaMotzi, on the other hand, stresses the value these elements have acquired by leaving the earth and becoming life-sustaining bread.

What does this have to do with the Exodus from Egypt?

The elements that are used to make bread started as part of the overall environment — the Earth — and were then separated for their special function. So, too, the Jewish people started out as part of humanity. Their unique character and holiness were revealed when God took them out of Egypt. “I am the Eternal your God, Who brings you forth from under the subjugation of the Egyptians.”

Like the blessing over bread, God’s declaration highlights two contrasting qualities: the interconnectedness of the Jewish people to the rest of the world; and their separation from it, for the sake of their unique mission.

(Adapted from Olat Re’iyah vol. II, p. 286)

0 notes

Text

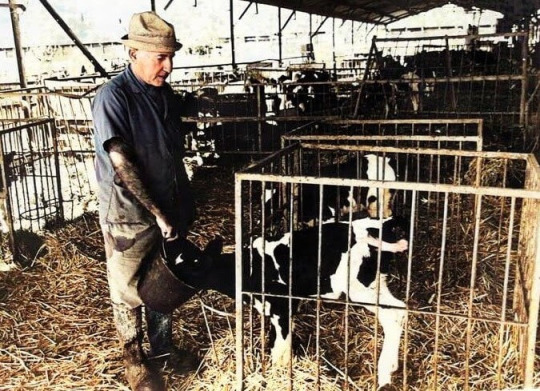

Ekev: Animals Served First!

The Torah promises that if we observe the mitzvot and sincerely love God, we will enjoy timely rain and bountiful crops:

וְנָתַתִּי עֵשֶׂב בְּשָׂדְךָ לִבְהֶמְתֶּךָ וְאָכַלְתָּ וְשָׂבָעְתָּ׃

“I will give plants in your field for your animals; and you will eat and be satiated.” (Deut. 11:15)

Rav Abba Aricha, the celebrated third-century scholar, called attention to the order of the verse: first the animals eat, and only then the people. He learned from here that one should not eat before first placing food before one’s animals.

Why is this? Should not people eat first, since they are more important? Are not human beings "the crown of creation"?

Rav Kook explained that this Talmudic rule of etiquette contains several moral lessons:

Given our central place in the universe, we have a responsibility to look after all creatures.

Our food (and in the case of the farmer, also his livelihood) is supplied by cows, chickens, and so on. We should feed these animals first as an expression of the fundamental gratitude we should feel toward these creatures which provide us with our basic needs.

If we lack food for a short time, we may comfort ourselves with spiritual or intellectual pursuits. This is an integral aspect of the human soul, which is not sustained “by bread alone.” Animals, however, have no such alternate outlets when they are pained by hunger. Therefore, it is logical to deal with the animal’s hunger first.

In purely physical aspects, animals are superior to humans. Is there a human being who is stronger than a bear, faster than a horse, more agile than a cat? Our superiority over animals lies exclusively in the spiritual realms: in our intelligence and our higher aspirations. Therefore, when it comes to physical sustenance, animals take precedence to humans, and by right are served first.

0 notes

Text

LISTEN IN AND UNDERSTAND!!!!

The True Tzadik

By going to to the true tzadik, one can, even now, be part of the true Torah's revelation. Like Moshe, the tzadik has the power to elevate those dependent upon him, so that when he gives a Torah lesson their souls play an integral part in the insights the tzadik reveals. Not only this! From the lesson we can likewise understand that by going to the tzadik, one comes under the direct and caring Divine providence of G-d's "seeing eye" (Mai HaNachal)

~ (Likutey Moharan #13:4,5)

Connecting to Sinai…

The ancient Hasid taught his disciples concerning learning and applying his Torah teachings:

“Everyone then who hears these words of mine and does them will be like a wise man who built his house on the rock. And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on the rock. And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not do them will be like a foolish man who built his house on the sand. And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell, and great was the fall of it.”

~ (Yeshua of Nazareth)

Being connected to the sichel (spiritual wisdom) of the tzadik which is grounded and founded on the holy Torah one is then connected to the same wisdom. The tzadik is a member of the Children of Israel, he shares in the collective soul of Israel and was present at Matan Torah (the giving of the Torah) on Mt Sinai. He is connected to the Mesorah, the chain of transmission passed on from Moses to today. Amazingly, even a non-Jew who is connected to the tzadik can share in this holy wisdom.

“If one finds his father’s lost item and his teacher’s lost item, tending to his teacher’s lost item takes precedence, as his father brought him into this world, and his teacher, who taught him the wisdom of Torah, brings him to life in the World-to-Come.”

~ (Bava Metzia 33a)

#ConnectingToTheTorah

#ViaMitzvot

#ConnectingToTheTzadik

#TheChainOfTransmission

B”H

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why Kiddush on Wine?

In this week’s parasha, Nasso, the Torah commands that a nazir is to abstain from wine and any other grape products. Wine appears frequently in the Torah, and plays a huge role in Judaism. Every Shabbat and holiday is ushered in with kiddush on wine, and concludes with a wine havdallah. Every wedding has a blessing on wine under the chuppah, as does a brit milah, and in ancient times wine libations were brought in the Temple. What makes wine so special?

The numerical value of “wine” (יין) is 70, a most significant number. It reminds us of the seventy names of God, of the seventy root nations of the world, and the seventy “faces” of Torah understanding. Our Sages famously stated that nichnas yayin, yatza sod, “when wine enters, secrets come out”. More than a simple proverb, it is a mathematical equation since the value of “secret” (סוד) is also 70. So, as seventy comes in, seventy comes out. On the surface level, the statement means that alcohol makes a person more likely to spill their secrets. On the deeper level, though, the Sages meant that one who drinks wine may be able to enter a mental state where they can uncover the secrets of Torah, and see it through all seventy faces. Wine can make “a man’s mind more receptive” (Yoma 76a).

Our Sages taught that wine is unique in that it defies the natural order: whereas other things degrade over time (as encapsulated in the second law of thermodynamics, the law of entropy, that the universe always tends towards disorder), wine improves and gets more valuable over time. Wine has another incredible scientific quirk: Japanese scientists researching electrical superconductors had a party in their lab and ended up accidentally discovering that wine makes certain metals superconductive!

Superconductivity refers to the property of being able to transmit electricity perfectly with no resistance and no energy loss. Generally, superconductivity requires cooling substances to near absolute zero (-273ºC). Some substances are able to superconduct at higher temperatures, around -90ºC, but even this is far too cold to be practical. Scientists around the world are therefore on the hunt for a room-temperature superconductor which, if found, would completely revolutionize the world. It would result in dramatic energy savings, and would allow for other cool phenomena like “quantum levitation”.

The Japanese scientists found that wine makes some things superconductive, especially iron-based compounds. And red wine especially was up to seven times more effective than other alcoholic beverages. No explanation for this has yet been found. It is all the more significant when we consider the central role that electricity plays in Jewish mysticism, and that our brains literally run on electrical signalling (suggesting how wine might make our brains more receptive to Torah secrets!) and that our bodies are full of iron, which makes our blood red, too.

While all of the above is fascinating, it does not explain why wine is so prevalent in Jewish rituals, especially in the recitation of every kiddush. What is the reason for wine?

Tree of Knowledge

The Zohar on this week’s parasha identifies the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden with the grapevine (this identification is also made in the Talmud in multiple places). Previously, the Zohar (I, 36b) had already suggested that what Eve actually did was make wine and serve it to Adam. So, it was the misuse of wine that resulted in evil and death being brought into the world. Thus, the spiritual rectification for this is to make kiddush on wine, thereby sanctifying and rectifying it, and reversing the damage that it caused. This explains why it is customary to say l’chaim, “to life”, before reciting the kiddush blessing (and toasting l’chaim more generally when drinking) since the idea is to reverse the death that was brought into the world through wine. In fact, our Sages state that one of three things that can shorten a person’s life is not reciting kiddush on wine! (Berakhot 55a) However, it must be said that this does not mean wine should be consumed in copious amounts—on the contrary, our Sages teach that wine is one of eight things that are only good in minute quantities and very harmful in large quantities (Gittin 70a).

Once we grasp the connection between the Forbidden Fruit and wine, we can answer many more questions. For instance, the timing of the Friday evening kiddush since, as per tradition, the sin of Adam and Eve took place on Friday, right before Shabbat. It also helps to explain the blessing on wine at a brit milah, where a newborn is officially brought into the Covenant, to rectify the breaking of the first covenant that God made with man. More specifically, Adam had been created whole, with no foreskin, and the foreskin only grew out after as a consequence of the consumption of the Forbidden Fruit (see Sanhedrin 38b, as well as Or HaChaim on Leviticus 12:2-3). So, it is fitting to make a blessing on wine at the ceremony in which that barrier is removed and a child is restored to a wholesome, original human state.

It is a similar case with the blessing on wine under the chuppah. Adam and Eve represent the first marriage, which was ruined by the Forbidden Fruit. In fact, Adam and Eve had separated for 130 years afterwards (which is why their third child Seth was only born 130 years later). Again, the wine under the chuppah serves as a rectification for marriage, and a blessing for the newlyweds to be able to establish a proper and holy “Garden of Eden” of their own.

We can also answer the classic question on this week’s parasha of why the nazir had to bring a sin offering at the end of his nazirite period. Why is a sin offering required—is not a nazirite vow a good thing? We can posit that by abstaining from wine, a nazir was simultaneously abstaining from kiddush and wine blessings, thereby failing to fulfil a critical tikkun for the world. As such, when the nazirite vow was over, a sin offering was required!

Finally, we can appreciate the extremely strict prohibitions on non-kosher and non-Jewish wine, or yayin nesekh. Since wine has such immense spiritual power, it is used (and misused) in other religions as well, and was widely used in ancient idolatries. One of the 613 mitzvot is to completely avoid the consumption of such idolatrous wines. The term yayin nesekh actually comes from parashat Ha’azinu where God warns that He will severely punish those who drink yein nesikham, the libation wine of idolaters (Deuteronomy 32:38).

Having said that, it is worth clarifying that there is a distinction between yayin nesekh, “idolatrous wine”, and yayin shel nokhrim, “gentile wine” more broadly. As the Rambam explains (see Sefer haMitzvot on Negative Mitzvah #194) the Torah itself did not forbid all wine made by non-Jews, just those made for idolatrous purposes or used in idolatrous rituals. Nonetheless, one of the famous 18 stringencies of Beit Shammai that were pushed through the Sanhedrin some 2000 years ago included a ban on all gentile-made wine, as an extra precaution. This is why, although we are unwaveringly stringent on this today, there have been lenient opinions in the past when it came to drinking wine made by non-Jews, as long as it was not yayin nesekh, of course (as most commercial wines are today, which are mass-produced and not involved in any kind of idolatry). Among those who were lenient on the matter include Rabbi Moshe Isserles (the Rama), Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh of Modena (of whom we previously wrote here), and Rabbi Shmuel Yehuda Katzenellenbogen of Venice. (Their positions, and how they have mostly been censored today, was discussed in Shapiro’s Changing the Immutable, ch. 3.)

10 Laws of a Kiddush Cup

The Talmud (Berakhot 51a) lists ten key rules regarding a kiddush cup (specifically one that is used when reciting birkat hamazon with wine, but also applying to any “cup of blessing”). First, it must be rinsed from the outside, and second, washed thoroughly from the inside. It must be filled with wine that is chai, “alive”, likely referring to undiluted wine, or perhaps wine that is still fresh and has not soured. (We can understand what the Sages meant on a mystical level when they said it must be “alive” in light of what was explored above.) The cup should be filled to the top, “adorned and wrapped”, raised with both hands, held in the right hand, lifted at least a handbreadth above the table, and gazed upon when reciting the blessing. Some also add that it must be passed around to the family to spread the blessing to them, especially to one’s wife.

“Adorning” the cup means beautifying the mitzvah in some way, such as when Rav Hisda would surround the kiddush cup with other cups. Using a special, decorated cup as opposed to a plain cup is enough to fulfil this requirement. The meaning of “wrapped” is less clear, and some say it means the person should be enwrapped with a tallit, while others say it means one should have their head covered, or wear a special hat. (In those days, it was encouraged but not yet halachically required for men to always have their heads covered, see more in ‘The Kabbalah of Kippah’.)

As with all things ten, the ten requirements of a kiddush cup parallel the Ten Sefirot, allowing for a complete rectification to be accomplished on all levels through the kiddush. The Ben Ish Chai beautifully comments that a human being is also called a “cup”, and these ten requirements apply to each and every one of us: to be well “rinsed” and hygienic from the outside, as well as thoroughly “clean” and pure on the inside. To be “alive” and righteous (for the wicked are called “dead”), and to be “full” of mitzvot and good deeds. To be “adorned” with Torah and to be “wrapped” spiritually with a holy aura. To live a life of balance between “both hands”—the right side of Chessed and the left side of Gevurah—but to prioritize the “right hand” of kindness when it comes to others. All of this will surely bring a person to be “raised a handbreadth”, the four-finger-length of which alludes to ascending the four olamot of Asiyah, Yetzirah, Beriah, and Atzilut, and then coming to stand whole before God, Who will “gaze upon” the individual and send blessings to his family.

Noah’s Wine and Mashiach’s Feast

No discussion of wine can be complete without mention of Noah’s vineyard. Following the Great Flood, Noah established the first vineyard, and then made wine and became drunk, with the unfortunate story that follows. The Midrash (Tanchumah, Noach) states that when Noah planted that first vineyard, Satan came and “slaughtered” four animals over it, with their blood seeping into the soil and giving their qualities to all subsequent alcohol drinkers: First was a sheep, for when one drinks a little bit they become “soft” like a sheep. Second was a lion, for when one drinks a little more they become haughty, proud, and bold. The last two were a pig and a monkey, for when a person drinks too much they inevitably urinate, vomit and frolic in filth like a pig, and become uncontrolled, wild, and foolish like a monkey.

That Midrash begins with Satan asking Noah what he was doing, and what the purpose of the wine would be. Noah explained that it can make people happy, and we can understand why he might have needed some joy after seeing the greatest global catastrophe of all time and the complete destruction of mankind. However, there was much more to it. The Zohar (I, 73a) says that Noah really wanted to penetrate deeper into the spiritual realms and see the divine. After all, wine is able to make the mind and soul more receptive to spiritual realities.

I believe Noah was attempting to rectify Eden himself. This is why the Zohar here says that Noah actually got the vine from the Garden of Eden. Further proof for this comes from the Torah’s exact language: when God planted Eden the Torah uses the rare verb va’ita (ויטע), and the very next appearance of this unique word is when Noah plants the vineyard. The third and final use of the term in the Torah is when Abraham plants an eshel, completing the first phase of the rectification process.

Amazingly, there is just one more instance of the word va’ita (ויטע) in all of Tanakh, found amidst the End of Days prophecies of Daniel (11:45). It sets up the very next verse which states that in those difficult times, the great angel Michael will arise to save God’s people, and “many that sleep in the dust of the earth will awake to eternal life…” Indeed, Noah’s purpose in making wine was to restore life, and the Midrash cited above quotes Noah telling Satan: l’chayei! His goal was “to life”, to reverse the death and evil of Eden and to rebuild a perfect world.

With each of our own l’chaims at every kiddush, we bring the world one step closer to that eventuality. And when it does come, and the righteous celebrate at the “Feast of Mashiach”, the Zohar (I, 135b, Midrash haNe’elam) states that a most special wine will be served, one that was cellared all the way back at the Six Days of Creation and has been aging ever since, waiting for the day when the world would be ready for it.

Shabbat Shalom!

0 notes

Text

Ohr Chaim on B’midbar 1:1

HASHEM SPKOE TO MOSHE IN THE WILDERNESS OF SINAI, IN THE OHEL MOED, ON THE FIRST OF THE SECOND MONTH, IN THE SECOND YEAR ..

Or HaChaim addresses what appears to be a difference between the Torah's description of where Hashem spoke to Moshe and its description of when He spoke to Him:

Our Sages, of blessed memory, expounded precious insights on the basis of the language of this verse (see Bamidbar Rabbah $1); but what remains for us to note and address is why Hashem, blessed be He, did not present the details of the verse in a consistent manner.

For when He tells us of where He spoke to Moshe, He first mentions the general setting, which is the Wilderness of Sinai, and only afterward mentions the specific location within the Wilderness of Sinai, by saying, in the Ohel Moed; but when He mentions when He spoke to Moshe, He first mentions the specific date by saying, on the first of the second month, and only afterward mentions the more general time frame by saying, in the second year after their exodus from the land of Egypt. This needs to be explained, because one would have expected the Torah to record both where and when Hashem spoke to Moshe in the same manner.

Or HaChaim suggests an answer:

It appears correct to say that, to the contrary, the verse ingeniously communicated the location and the date of Hashem's words to Moshe in a consistent manner. For although the Wilderness appears to be larger than the Ohel Moed, the latter is really more encompassing, as will soon be explained. Thus, even when discussing where Hashem

spoke to Moshe, the Torah begins with the less encompassing, and then moves to the more encompassing. This idea, that the Ohel Moed was more encompassing than the Wilderness, can be understood on the basis of what [the Sages] say (Bereishis Rabbah 68:9) in explanation of the verse (Shemos 33:21), Behold there is a place with Me, in which the Torah describes a place as being "with Hashem" rather than saying that Hashem is in a place.

This, the Sages teach, conveys that the location in which the Holy One, blessed is He, is manifest, is subordinate to Him (Bereishis Rabbah 68:9), for since Hashem transcends space, the universe is not His location, but, to the contrary, He, so to speak, is the location of the universe. Accordingly, all places are subordinate to a place in which God "encamps," i.e., where His Shechinah is more manifest. Thus, when this principle is applied to the locations mentioned in our verse, it emerges that the more encompassing area is actually the Ohel Moed,

where the Shechinah rested, and the Wilderness is a specific place that is subordinate to [the Ohel Moed]. Thus, even when speaking about where Hashem spoke to Moshe, the verse begins with the less encompassing (the Wilderness), and then moves to the more encompassing (the Ohel Moed). To make you aware of this idea that the Wilderness is less encompassing than the Ohel Moed, the verse places the statement, on the first of the second month in the second year, right after it discusses where Hashem spoke to Moshe.

Since that phrase clearly begins with the less encompassing (the specific date) and proceeds to the more encompassing (the year), we therefore understand that in the Torah's description of where Hashem spoke to Moshe, the statement, in the Ohel Moed, is a description of the more encompassing location; and that is why it is placed last, after the phrase, in the Wilderness,

in keeping with the order that the Torah followed when describing when Hashem spoke to Moshe, where the second year, the more general time frame, is placed after [the Torah] says, on the first of the second month, the more specific date.

Or HaChaim expands on the effect that Hashem's Presence has on the physical characteristics of an area:

You can se how immense is a place in which Hashem is more manifest from what we find occurred in the time of Yehoshua; namely, that within the two amos and a bit that were between the two poles of the Aron, a place where the Shechinah rested, six hundred thousand Jews were able to stand comfortably (see Bereishis Rabbah 5:7) this you see that even though [this area] between the two poles of the Aron is relatively small to the naked eye, it is in fact very large on account of the One Who dwells there, blessed is He.

#B’midbar#Ohel Moed#Shechinah#Moshe#B’reshit Rabbah 68:9#HaShem spoke#Shemot 33:21#B’reshit Rabbah 5:7

1 note

·

View note

Text

PROLOGUE From The Sabbath-Architecture Of Time.

Technical civilization is man's conquest of space. It is a triumph frequently achieved by sacrificing an essential ingredient of existence, namely, time. In technical civilization, we expend time to gain space. To enhance our power in the world of space is our main objective. Yet to have more does not mean to be more. The power we attain in the world of space terminates abruptly at the borderline of time. But time is the heart of existence.'

To gain control of the world of space is certainly one of our tasks. The danger begins when in gaining power in the realm of space we forfeit all aspirations in the realm of time. There is a realm of time where the goal is not to have but to be, not to own but to give, not to control but to share, not to subdue but to be in accord. Life goes wrong when the control of space, the acquisition of things of space, becomes our sole concern.

Nothing is more useful than power, nothing more frightful. We have often suffered from degradation by poverty, now we are threatened with degradation through power. There is happiness in the love of labor, there is misery in the love of gain. Many hearts and pitchers are broken at the fountain of proft. Selling himself into slavery to things, man becomes a utensil that is broken at the fountain. Technical civilization stems primarily from the desire of man to subdue and manage the forces of nature. The manufacture of tools, the art of spinning and farming, the building of houses, the craft of sailing-all this goes on in man's spatial surroundings. The mind's preoccupation with things of space affects, to this day, all activities of man. Even religions are frequently dominated by the notion that the deity resides in space, within particular localities like mountains, forests, trees or stones, which are, therefore, singled out as holy places; the deity is bound to a particular land; holiness a quality associated with things of space, and the primary question is: Where is the god? There is much enthusiasm for the idea that God is present in the universe, but that idea is taken to mean His presence in space rather than in time, in nature rather than in history; as if He were a thing, not a spirit.

Even pantheistic philosophy is a religion of space: the Supreme Being is thought to be the infinite space. Deus sive natura has extension, or space, as its attribute, not time; time to Spinoza is merely an accident of motion, a mode of thinking. And his desire to develop a philosophy more geometrico, in the manner of geometry, which is the science of space, is significant of his space-mindedness.

The primitive mind finds it hard to realize an idea without the aid of imagination, and it is the realm of space where imagination wields its sway. Of the gods it must have a visible image; where there is no image, there is no god. The reverence for the sacred image, for the sacred monument or place, is not only indigenous to most religions, it has even been retained by men of all ages, all nations, pious, superstitious or even antireligious; they all continue to pay homage to banners and flags, to national shrines, to monuments erected to kings or heroes. Everywhere the desecration of holy shrines is considered a sacrilege, and the

shrine may become so important that the idea it stands for is consigned to oblivion. The memorial becomes an aid to amnesia; the means stultify the end. For things of space are at the mercy of man. Though too sacred to be polluted, they are not too sacred to be exploited. To retain the holy, to perpetuate the presence of god, his image is fashioned. Yet a god who can be fashioned, a god who can be confined, is but a shadow of man.

We are all infatuated with the splendor of space, with the grandeur of things of space. Thing is a category that lies heavy on our minds, tyrannizing all our thoughts. Our imagination tends to mold all conceptsin its image. In our daily lives we attend primarily to that which the senses are spelling out for us: to what the eyes perceive, to what the fingers touch. Reality to us is thinghood, consisting of substances that occupy space; even God is conceived by most of us as a thing.

The result of our thinginess is our blindness to all reality that fails to identify itself as a thing, as a matter of fact. This is obvious in our understanding of time, which, being thingless and insubstantial, appears to us as if it had no reality.

Indeed, we know what to do with space but do not know what to do about time, except to make it subservient to space. Most of us seem to labor for the sake of things of space. As a result we suffer from a deeply rooted dread of time and stand aghast when compelled to look into its face.' Time to us is sarcasm, a slick treacherous monster with a jaw like a furnace incineating every moment of our lives. Shrinking, therefore, from facing time, we escape for shelter to things of space. The intentions we are unable to carry out we deposit in space; possessions become the symbols of our repressions, jubilees of frustrations. But things of space are not fireproof; they only add fuel to the flames. Is the joy of possession an antidote to the terror of time which grows to be a dread of inevitable death? Things, when magnified, are forgeries of happiness, they are a threat to our very lives; we are more harassed than supported by the Frankensteins of spatial things.

It is impossible for man to shirk the problem of time. The more we think the more we realize: we cannot conquer time through space. We can only master time in time.*

The higher goal of spiritual living is not to amass a wealth of information, but to face sacred moments. In a religious experience, for example, it is not a thing that imposes itself on man but a spiritual presence." What is retained in the soul is the moment of insight rather than the place where the act came to pass. A moment of insight is a fortune, transporting us beyond the confines of measured time. Spiritual life begins to decay when we fail to sense the grandeur of what is eternal in time.

Our intention here is not to deprecate the world of space. To disparage space and the blessing of things of space, is to disparage the works of creation, the works which God beheld and saw

"it was good." The world cannot be seen exclusively sub specie temporis. Time and space are interrelated. To overlook either of them is to be partially blind. What we plead against is man's unconditional surrender to space, his enslavement to things. We must not forget that it is not a thing that lends significance to a moment; it is the moment that lends significance to things.

0 notes