philosophy in permadeath mode; make mysticism great again

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The polar star

The polar star is not a sign: one can use it to navigate precisely because it’s perceived to be inscribed in our space, it actually is in space – so we can use it for direction. However the actual space being navigate is the surface of the Earth, and the polar star is not a part of it. Indeed it is so far away that it is almost like a sign. Sometimes you can’t tell where the sign-space ends and the real-space begins, but those points aren’t reachable – they are only useful for the navigation anyway.

0 notes

Text

The myth of thinking; the thought-fantasy

A very important experience is described by many people along the lines of ‘I wanted to say something but couldn’t find the right words’. It is usually interpreted as – and this interpretation is suggested by the way the experience is described – as if there was some kind of ‘real idea’ somewhere in the mind which was very hard, even impossible, to put into words. Now we have to expose this ‘real idea’ as a myth, I’d even say a complete, harmful, depression-inducing bullshit.

We have to distinguish between an actual thought and a fantasy of having one. If you’ve ever tried any other medium (painting, programming, woodcutting, cooking, whatever), haven’t you ever had this experience of fantasizing about a particular outcome, which quickly proved to be impossible, or unreachable without much harder work than this particular fantasy would allow, just because the medium doesn’t work this way? You say: I’ll make a computer program to understand German; I’ll paint a painting which would transcend the; I’ll program a computer game without any oppressive binary oppositions; I’ll cook a cake provoking a novel sense of taste… Ah but of course you will. Now what makes you think that it’s not the same with thought?

What could even this ‘real, inexpressible idea’ be? Probably something very banal and stupid, some kind of a commonplace. Remember trying to summarise a complex and exciting book to a friend? ‘Well there’s this and that… in the end, you know, everything is connected!’. Is that the ‘great idea’ of the book? How disappointing. Yet a lot of people come to some kind of a statement like that and let it guide their life. Most of the time it leads to depression: ‘Nothing matters’, ‘There’re no free acts’, blah-blah-blah. Those are not ideas. Those are just fantasies about having them. Those are basically delusions of the mind’s grandeur: ‘I could make nothing matter’, ‘I could connect everything’.

Now there is a thing to do every time you see a generalization. Just ‘instantiate’ it, just show it with a example, a new one. Everything is connected? Pick any two things which never seemed connected and show how they’re connected (and you’ll either write an actual exciting historical, sociological, genealogical essay – or you’ll see how this idea has limits and will be able to write about them). Nothing matters? Prove that a thing doesn’t matter, be brave, make nonsensical something which seems sensible to you – if you’re not a coward, this will end up being very bravely political very quickly. Yes, don’t be a coward, try to achieve your fantasies, even the fantasies about thinking – you won’t achieve the same thing, but you’ll achieve a better one.

It’s one thing to evaluate things in thinking, and the whole other thing is to actually use those evaluations as your guide. You can dislike the concept of the subject, you can fight the binary oppositions, you can despise the generalizations; but can you actually write meaningfully without these things? I’m not saying that you absolutely can’t – I’m just saying that it takes very hard work, and this hard work is (in the best cases) what makes the actual philosophical text so different from its summary on the cover. Having an opinion about everything is easy; actually working on your thought so that it follows your values is an exciting opportunity to do some great thinking.

Now this all comes from the recognition that an idea and a fantasy about an idea are completely different. I want to go further and say: the thinking works just like any other medium, that is – it is material in a very meaningful sense (obviously not the stupid one, it’s not atoms, but in the one Aristotle had it). It’s something to work with. It’s something that has more of a subtle resistance than any logical structure. The actual opposition is not between the thoughts and the material, but between the material and the fantasies.

0 notes

Text

Why have the capitalism invented death?

Maybe in the continental tradition the question of an AI and its consciousness should be approached from the position of whether an AI can die. We can consider the qualities of the consciousness, that we feel how it’s continuous, undivided and unique. Setting aside the question of whether those are ‘real’ or illusory, we can just ask is there an AI that could exhibit those qualities. At the first glance, no – any, say, neural network can be saved as a file, copied, resumed. It is this possibility to save it that makes it too ‘material’, as the supposed non-materiality of the consciousness might be exactly the way to look at the fact that it can’t be saved (I haven’t even considered yet the theological connotations of the word). I’d argue that if we make a mortal AI we’ll have something much crazier and closer to the human than any know-it-all one.

On the other hand, we can imagine ways to make it feel closer to this set of qualities. E.g. legally – say, a neural network is licensed to run ‘in the cloud’, ‘as a service’ of a provider to a client, with the terms forbidding provider to look inside of the network (at the risk of accessing the client’s private data), on the other hand with the technical prohibition of the client to do the same (at the risk of it not needing the services of the provider anymore). Now the network can’t be saved or copied; it can die.

So we actually come to another question, which is the same one but in reverse: Why have the capitalism invented death? What were its technical means to do this, and to what end? Remember how Freud (quoting someone, likely) replied, that the death is there because of the sexual reproduction; we die so that we give birth to the children which are not us. So one way an AI can die is by creating something that obsoletes it.

0 notes

Text

Pure waste of bandwidth

A few Girard-inspired, mathematical-theological stories for my friends.

Voting for itself. Girard dismisses the Hilbert’s programme, comparing the attempt to prove mathematics using mathematics to “the parliament voting for itself”. It is a correct comparison, yet its value as a criticism is ambiguous. As a french logician, Girard might actually know that the French Republic – and arguably the modern politics – has actually been founded with the parliament voting for itself. In 1789, the new-founded National Assembly of France was concerned with the question, whether it actually does represent the general will? This question was resolved affirmatively by the notorious Abbé Sieyès, who took the structure of his argument from the catholic thinker Nicolas Malebranche.

Malebranche was concerned with proving prothestants wrong, as catholics usually are. The problem was, whether the Catholic Church, that is, its body of cardinals was the one, unique representation (in the yet religious sense, from which we will later found the legal concept of representation) of God on Earth – as opposed to the possibility of the multiple, partial, conflicting representations of his will favored by the protestants. His thought experiment was simple: “Say we gather all of the cardinals together and let them take a vote, whether they, together, do or do not represent the god’s will. The ones who say ‘no’ are obviously not real cardinals: you can’t be a cardinal if you don’t believe in the institution. So everyone who is a real cardial will say ‘yes’, thus determining by unanimous vote that the Catholic Church is indeed the one and unique representant of God”.

Now let us postpone the matter of the obvious begging-the-question; let us also not indulge for now in the beautiful ways with which Malebranche tries to fix it; let’s focus on how this argument is still at work in our very lives. Abbé Sieyès used this very same argument to prove that the Assembly is the real representative: if your particular will is against it, you’re just not of the Republic and your will doesn’t count. The whole seeming ridiculousness of the argument pales in comparison with its incredible effectiveness: the modern politics was born with all its representative-democratic weirdness. There’re likely philosophical ways to ground this idea onto something more fundamental, yet the notoriousness of such an ouroboric event is clear, and the break that happened here is on the level of a new self-supporting thought from which, however, the ‘real things’ are being created on a daily basis.

Can’t we say that Hilbert’s programme is the same type of event, just imposed kind of retrospectively onto the history of mathematics? The mathematics voting for itself, let the naysayers be damned into luddistic hell? In this case we can go on living with its theological form while embracing the fruitful mathematical content it gave us. And then our next move, the move of the ones who dares to respect and use mathematics without believing in it, should obviously be to look for the heretics and the heretical thoughts. We should not be content with those who just dismisses mathematics altogether (the boring, impotent atheists) – the real heretic is the one who is of the mathematical practice, but questions its belief structure. How do you call the hagiography but about heretics? Heretography?

Hysterizing the computer. Now one of those heretics is Brouwer, whose whole project was about questioning the givenness of the a priori. Insane idea, completely against Kant, of course, as it questions the very distinction between thinking and praxis. A priori as something completely given assumes some kind of a collapse of the process of thinking in time, with all of the theorems already there somewhere, indeed nothing more than Anselm’s ontological argument, but about mathematics. Brouwer scouted this a priori and found his own fixed point theorem, which states that there’s something that exists but can’t be found. Now that’s unsettling for Brouwer who is, by the way, of a Schopenhauer’s persuasion. To question the whole thing, Brouwer looks for the most extreme point of this a priori givenness, and it’s nothing else but the law of the excluded-middle: it’s only there if you can always do the anselmnian jump to the farthest conclusion. Brouwer slows down this seemingly instantaneous jump by denying it, inventing the intuitionistic logic, and actually somehow manages to get pretty far with it, reformulating even a part of topology in this new light. However this heresy was not approved by his holiness Hilbert, already too influential on the continent – isolated Brouwer loses his mind and dies, never seeing any hope of his work being useful.

A different development was up at the same, however, concerned a piece of metal to be called computer. There were a few of those machines already, and it was obvious that there’s going to be more. On the other hand, it didn’t actually take very long for people to notice how incredibly useful the intuitionistic logic was for this machine: much more than the ‘classical one’. The computer became the redeeming object of Brouwer’s logic – he never saw one, never even thought of one, yet turned out to provide the most important concept for its study. The depth of Brouwer’s premature contribution to Computer Science is beyond the wariness of tertium non datur: his work predicted the notorious problems with the floating-point numbers, and his topology turned out to be a weird tool to study computable functions, which is a cross-sub-disciplinary link of strange awesomeness for the easily excitable people like me.

So if we’re desperately looking for any escape from the horrible weight of the Kantian-Hilbertian mathematical theology, shouldn’t we look into the computer? One of the weird things about the computers is how easily we all were persuaded, not so long ago, that everything in the computer is “virtual” (not in the sense in which philosophers use the epithet, but in the sense the marketers use it), that is, not exactly material… Which is nonsense, a structure of disavowal, which has to be thoroughly contradicted on all the levels, starting on the level of primitive processor instructions which, according to the simplest laws of thermodynamics, can’t perform any destructive operation – can’t forget any value of any variable – without wasting some energy, emanating some heat. This kind of thought is as material as it can be.

Right here, right now, I can show you how the materiality of computer affects our everyday life in a very noticeable, annoying fashion. Let us recall that to study the whole population of computers a special concept was invented, ‘the Turing machine’. It was a strange abstraction, seeking to provide an ideal type for those machines, a link between their real bodies and the computable functions which are performed by them. It is used in science, yes, but it is also used too much in the arguments between the adolescent programmers, if you ever dared to talk to them – “C and Lisp are the same thing because of the Turing machine”... But let’s leave them be. Where’s the Turing machine’s fault?

Turing machine is imagined to have an infinite time and an infinite memory space. That’s what we can sometimes believe about our computers. When our computers run out of time – that is, we subjectively feel that they are slow – we’re annoyed and happy to fix it. The existence of the computer as a time-consuming device is obvious and we’re perfectly equipped to notice it; every second it’s slowing down we’re feeling it, I think, already at the level of our bodies; yet there’s no realistic limit to how long a computer can run. What is harder to notice, yet much more objective, is the limit of its memory: the computer runs just happily, using as much memory as it can, until there’s no more memory at all. Then strange things begin to happen.

What does exactly happen when the computer is out of memory? Of course, it can just kill the hungry program: it’s not part of the algorithm’s mathematical abstraction, but at least predictable. Usually, however, stranger things happen. One of the ways the computer pretends to have more memory than it actually does is by “swapping”: using the HDD instead of the RAM to store whatever is to be stored in memory. HDD is 10k times slower than RAM: when it’s used for memory too much, nothing crashes, but everything is suddenly very slow. We hear strange noises. The computer starts misbehaving. Random things crash because of the timing issues brought by the lack of speed.

Now we can allow ourselves to see this “lack of memory” in the aristotelian-lacanian light, as something that is material by being actively opposed to the (mathematical) form, not-reducible to it (if only to escape the attempt to inscribe the whole OS, other programs and the hardware into one big ad hoc mathematical structure making any mathematical study of the algorithms pretty much useless). I say “lacanian”, faithfully to Lacan (his Real was Aristotle’s matter), because this is indeed the very point where the subjectivity of computer in the lacanian sense is obvious: it lacks memory (desire) – it acts out (hysteria). If we consider how hackers use a similar problem, the buffer overflow, to do whatever they want to the computer, the analogy becomes rich enough.

The materiality of the neural network. In 1892, one W. E. Johnson described “symbolic calculus” as “an instrument for economizing the exertion of intelligence” (btw, Johnson is described by Wikipedia as “a famous procrastinator”). Far from enabling new types of intelligence by itself, the thing was to save on the wasted expenditure of the old ones. With this I want to introduce another dimension of the materiality of the computer: the one which I’ll describe from a paranoid-marxist perspective, following the Adorno’s belief in the truth of the exaggerations.

Neural network is an amazing shiny new thing, it economizes our exertion of intelligence all right, yet the weirdest part of it all is that we kinda have no idea how it works. We can describe the output (in our terms which we impose on it), and we can describe the inner structure (it’s all matrix multiplication), but there’s no translation between the output and the inner structure except for the one that is by running the neural network themselves. The neural network’s thinking, in general, lacks the conceptual content we’re so much used to, it doesn’t exactly distinguish the parts of bodies and stuff like that. It operates on a belated, not-yet-conceptual level. We can actually through pain identify some general things that it actually notices on the images and stuff like that, but only partially and constantly recognising that it’s we who’s pulling the vague ideas of the NN to this conceptual level.

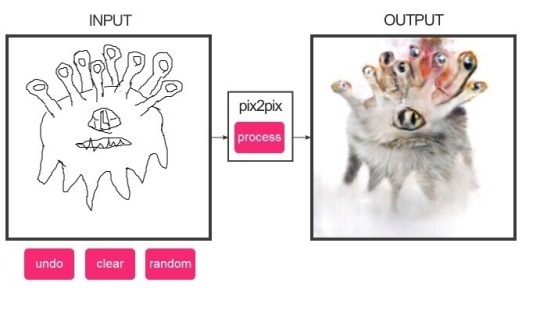

To illustrate how the NN works there’s no better example than the notorious network which draws cats upon sketches of cats: http://affinelayer.com/pixsrv/index.html . Try it out, you can do it online. Now, what are the concepts with which the neural network thinks about cats? It’s… well, it knows an eye, but that’s more-or-less it. Everything else is more like a texture of a cat, in a very weird sense of a texture, the one available to us after we discovered the 3D rendering.

So there’s knowledge of things in the NN, yet it’s either not on the human level, or it’s somehow hidden. To explain this, Schopenhauer comes to mind: “an entirely pure and objective picture of things is not reached in the normal mind, because its power of perception at once becomes tired and inactive, as soon as this is not spurred on and set in motion by the will. For it has not enough energy to apprehend the world purely objectively from its own elasticity and without a purpose”. That is to say: NN understands cats exactly as much as it needs to (with the need imposed by its operators, most of the time the Capital), and no more.

Now the paranoid-marxist intervention: what is this lack of knowledge? Who has it? Is it not the proletariat? If we have a training set of thousands of pictures, on which a neural network is trained to recognize dozes of features, those features had to be tagged beforehand by some pure workers (most likely from India, am i right?), who themselves were likely constructed through a cheap-labor marketplace such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (the name familiar from Walter Benjamin), pretending to be machines to create a neural network which pretends to do the human work. Can’t we say, exaggerating, that the neural network is a labyrinth of numbers in which anyone looking for the human [labor] is to lose his track?

1 note

·

View note

Text

I hear of far places and old times when the electricity has not yet completely hidden the braille of the night sky. The fable describes how our ancestors recognized the deepness of sky in the shallowness of the lake’s surface. They saw their own faces on its surface as well. They saw that sky is chaotic... They likely had to invent the very word chaos for the occasion – and then to see that their fates are well-described by this word. To learn to read the chaos of the sky is to learn to read the chaos of life.

3 notes

·

View notes