Text

"The Spread of Christianity in the British Isles: Monastic Missions and Roman Authority Triumphs"

The spread of Arianism among Germanic tribes and the conversion of the Franks to Roman faith were noted. Catholic orthodoxy was gradually accepted by Germanic invaders. However, there was still much to do. The church's vitality during the collapsing empire and opening Middle Ages was shown through its successful extension of Christianity.

Ireland and Scotland

Christianity was present in British Isles before Constantine's conversion. The Roman Empire's downfall weakened it among the Celtic population, while the Anglo-Saxon invaders won much of southern and eastern England for heathenism. Christian beginnings were found mainly in southern Ireland before Patrick. However, he greatly advanced the cause of the Gospel in Ireland and organized its Christian institutions, earning the title of Apostle of Ireland.

Patrick was born in 389 and was the son of a deacon and grandson of a priest. He was trained in Christianity. In 405, he was taken as a slave in Ireland for six years. He was able to escape to the Continent and lived in the monastery of Lérins for some time. In 432, he was ordained a missionary bishop by Bishop Germanus of Auxerre. Patrick then began his work in Ireland, where he spent most of his time in the northeast, with some efforts in the south and west. Despite few facts surviving, there is no doubt about his zeal and his abilities as an organizer. He systematized and advanced Christianity in Ireland. Patrick brought the island into association with the Continent and with Rome.

Patrick introduced the diocesan episcopate into Ireland, but it was soon modified by the island's clan system, resulting in many monastic and tribal bishops. Finian of Clonard (470?-548) developed the unique Irish monasticism, which included strong missionary efforts and notably learned monasteries. The Irish monastic schools were famous in the sixth and seventh centuries, and the monasticism's greatest achievement was its missionary work.

The origins of Christianity in Scotland are unclear. Ninian and Kentigern spread the religion in the 4th and 5th centuries respectively, but not much is known about their work. There is a possibility that the Irish settlers who founded the kingdom of Dalriada in 490 were Christians. However, the most influential missionary was Columba. He founded a successful monastery on the island of Iona and went on to spread the Gospel among the Picts in the northern regions of Scotland. Christianity in Scotland was mainly monastic, with bishops under the authority of Columba and his successors as abbots of Iona.

Missionaries on the Continent

Irish missionaries brought Christianity to northern England, Lindisfarne. Aidan, a monk from lona, established a new Iona on the island in 634. Christianity was then widely spread in the region by Aidan and his associates. These Celtic monks were also active outside of the British Islands. Columbanus, a monk from the Irish monastery of Bangor, founded the monastery of Luxeuil in Burgundy. He later established the monastery of Bobbio in northern Italy, where he died a year later.

Columbanus was one of many Irish monks who worked in central and southern Germany. They introduced private confession to the laity, which was widely supported by the Irish monks. The Irish also created the first penitential books with appropriate satisfactions for specific sins. These books were made familiar on the Continent by the Irish monks.

Roman Missionaries in England

Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine, a Roman friend, and several monastic companions to convert the Anglo-Saxons. After much struggle, Æthelberht and many of his followers accepted Christianity. Augustine was then appointed as a metropolitan bishop and was authorized to establish twelve bishops under his jurisdiction. It took almost a century for Christianity to become dominant in England, but the movement strengthened the papacy and produced some of the most energetic missionaries on the Continent.

The acceptance of Christianity in England was not without difficulty. After the death of Ethelberht, the power of Kent declined, and with it the initial Christian successes. Northumbria gradually emerged as the leader. In 627, King Edwin of Northumbria was converted to Christianity through the efforts of Paulinus, who later became bishop of York. However, in 633, the heathen King Penda of Mercia defeated and killed Edwin, leading to a heathen backlash in Northumbria.

Under the Christian King Oswald, who had converted while in exile in Iona, Christianity was re-established in Northumbria with the help of Aidan, who represented the Irish or "Old British" tradition (see ante, p. 197). Penda attacked again, and in 642, Oswald was killed in battle. His brother, Oswy, like him a convert of Iona, struggled to secure all of Northumbria, finally succeeding by 651 and earning widespread recognition as an overlord. English Christianity was becoming firmly established.

Roman Authority Triumphs

Since the arrival of the Roman missionaries, there had been disputes between them and their Irish or Old British counterparts. The differences seemed minor, such as the older system of reckoning used by the Irish and Old British, which resulted in diversity regarding the date of Easter. Additionally, the forms of tonsure and the administration of baptism differed. The Old British Church was monastic and tribal while Roman Christianity was diocesan and organized. The Old British missionaries considered the Pope as the highest dignitary in Christendom, but the Roman representatives held him to have judicial authority which the Old British did not fully accept. Southern Ireland accepted the Roman authority around 630, while England made its decision at a synod in Whitby in 664 under King Oswy. Bishop Colman of Lindisfarne defended the Old British usages, while Wilfrid, previously of Lindisfarne but having won for Rome on a pilgrimage and soon to be bishop of York, opposed. The Roman custom regarding Easter was approved, securing the Roman cause in England. By 703, Northern Ireland had followed the same path, and by 718, Scotland. In Wales, the process of accommodation was much slower and only completed in the twelfth century. Pope Vitalian's appointment of a Roman monk, Theodore, as Archbishop of Canterbury in 668 further strengthened the Roman connection in England. Theodore, an organizer of ability, did much to make permanent the work begun by his predecessors.

The combination of the two streams of missionary effort proved advantageous for English Christianity. While Rome contributed order, the Old British added missionary zeal and a love of learning. The scholarship of Irish monasteries was transplanted to England and strengthened by frequent Anglo-Saxon pilgrimages to Rome. Bede, also known as the "Venerable" (672?-735), was a prominent figure in this intellectual movement. He spent most of his life as a member of the joint monastery of Wearmouth and Jarrow in Northumbria. Like Isidore of Seville a century earlier, Bede's learning encompassed the full range of knowledge of his time, making him a teacher for generations to come. He wrote on chronology, natural phenomena, the Scriptures, and theology. He is most famously known for his "Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation," a highly regarded work that is the principal source of information regarding the Christianization of the British Islands.

Annotated Bibliography

- *The Conversion of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms* by Richard Fletcher: This book provides a comprehensive overview of the spread of Christianity in England, including the role of Roman and Celtic missionaries and the conflicts that arose between them.

- *Celtic Christianity: Making Myths and Chasing Dreams* by Ian Bradley: This book explores the origins and development of Celtic Christianity, including its unique monastic traditions and how it influenced the spread of Christianity in the British Isles.

- *Saint Patrick's World: The Christian Culture of Ireland's Apostolic Age* by Liam de Paor: This book provides a detailed account of the life and work of Saint Patrick, including his mission to Ireland and his efforts to establish Christianity on the island.

- *Bede: The Ecclesiastical History of the English People* translated by Leo Sherley-Price: This classic work by the Venerable Bede is a primary source for the history of Christianity in England, providing valuable insight into the early church and its leaders.

- *The Life of Saint Columba* by Adomnan of Iona: This biography of Saint Columba, written by one of his contemporaries, provides a detailed account of his life and work as a missionary in Scotland and his establishment of the monastery at Iona.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The Life and Legacy of St. Thomas of Villanova: A Model of Charity and Humility"

"The Life and Legacy of St. Thomas of Villanova: A Model of Charity and Humility" - A look into the life of a saint and his impact on the Church.

The order that unknowingly supported this evil person was still accepted by God. He showed this to comfort groups that have excellent standards but sometimes have unworthy members who fall. Luther introduced his famous theses against indulgences and the authority of the Roman pontiff at Wittenberg during the first Vespers of All Saints. Thomas of Villanova pronounced his vows at Salamanca on November 25th of the same year. He filled the position that the Heresiarch left vacant. Despite the social disorder and disturbances in the world, the glory given by one saint to the ever-tranquil Trinity is more important than any insults or blasphemies from hell.

Thomas was born in 1488 in Fulana, Spain. From a young age, his parents taught him piety and to be charitable to the poor. As a child, he often gave his clothes to those in need. He later studied humanities at St. Ildefonsis in Alcala and, after his father's death, used his inheritance to support destitute virgins. Thomas returned to Alcala to complete his studies in theology and became a successful professor. He then joined the hermits of St. Augustine and excelled in virtues such as humility, patience, continence, art, and charity. Despite his many labors, Thomas remained devoted to prayer and meditation. He was a renowned preacher, leading countless souls to salvation, and was appointed to govern the Brethren, where he restored discipline in many places.

When elected to the Archbishopric of Granada, he rejected that high dignity with wonderful firmness and humility. But not long after, he was obliged by his superiors to undertake the government of the Church of Valencia, which he ruled for about 11 years as a most holy and vigilant pastor. He changed nothing of his former manner of life, but gave free scope to his insatiable charity and distributed the rich revenues of his church among the needy, keeping not so much as a bed for himself. For the bed on which he was lying when called to heaven was lent to him by the person to whom he had shortly before given it in alms. He fell asleep in our Lord in the sixth of the Ides of September, at the age of sixty-eight.

God bore witness to his servants' holiness through miracles both in life and after death. One miracle involved a barn, almost empty after corn was given to the poor, being suddenly filled by his intercession. Another involved a dead child being restored to life at his tomb. These and other miracles made his name famous. Pope Alexander VII declared him a saint and commanded his feast day to be celebrated on the fourteenth of the calends of October. Thomas, your name and justice will last forever. You gave all the church to the poor and your alms will be declared by all the saints. Teach us to show mercy to our brethren so that, through your prayers, we may obtain the mercy of God.

You had great influence with the Queen of Heaven, whom you loved to praise, and whose birthday on earth coincided with your birthday in heaven. Help us to know her better and love her more each day. You are a revered figure in Spain. Please watch over your country, the church of Valencia, and the order that has produced saints like Nicholas of Torrentino, John of San Facundo, and yourself. Bless the nuns who have inherited your generosity and have kept your name and that of your father St. Augustine honored for almost 300 years. May your writings continue to inspire preachers of the divine word all over the world, as they are a testament to the eloquence that made you an advisor to royalty, a guide for the poor, and a channel for the Holy Spirit.

The holy martyrs Maurice, Exuperius, Candidus, Victor, Innocent, and Vitalis, along with their companions of the Theban Legion, were massacred under Maximian for their Christian faith. They are remembered as valiant soldiers and patrons of Christian armies and churches. When asked to break their oaths to God, they refused, stating that they were soldiers but foremost servants of God.

Annotated Bibliography

- "St. Thomas of Villanova." Catholic Online. https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=234. Accessed 14 September 2021.

This article provides a brief overview of St. Thomas of Villanova's life, including his early years, education, and contributions to the Church. It also highlights the virtues for which he is known, such as his charity and humility.

- "St. Thomas of Villanova: Augustinian Bishop and Patron of Catholic Education." Augustinian Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova. https://augustinianvocations.org/st-thomas-of-villanova. Accessed 14 September 2021.

This article provides a more in-depth look at St. Thomas of Villanova's life and contributions to the Church. It includes information on his role as a bishop and patron of Catholic education, as well as his impact on the Augustinian order.

- "St. Thomas of Villanova: A Model of Charity." National Catholic Register. https://www.ncregister.com/commentaries/st-thomas-of-villanova-a-model-of-charity. Accessed 14 September 2021.

This article focuses on St. Thomas of Villanova's emphasis on charity, including his personal acts of charity and his teachings on the subject. It also discusses his impact on the Church and the legacy he left behind.

- "The Theban Legion." Catholic Online. https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=2020. Accessed 14 September 2021.

This article provides information on the martyrs Maurice, Exuperius, Candidus, Victor, Innocent, and Vitalis, as well as their companions of the Theban Legion. It discusses their faith and the circumstances surrounding their deaths, as well as their status as patrons of Christian armies and churches.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Anglican and Roman Catholicism Differences

A Brief Overview of Anglican and Catholic History

The Anglican and Catholic churches have a rich history that spans centuries. While both churches share many similarities, including a belief in the Holy Trinity and the sacraments, they also have significant differences in doctrine, liturgy, and governance.

The Anglican Church traces its roots to the English Reformation of the sixteenth century. In 1534, King Henry VIII declared himself the head of the Church of England, breaking away from the authority of the Catholic Church and paving the way for the development of Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer, introduced in 1549, became the standard for Anglican liturgy, and the King James Bible, published in 1611, remains an influential text to this day. Other significant events in Anglican history include the restoration of the episcopacy in 1660, the formation of the Methodist movement in the eighteenth century, and the first Lambeth Conference in 1867. In the twentieth century, the Anglican Church began ordaining women, and in 2003, Gene Robinson became the first openly gay bishop in the Anglican Communion. In 2009, the Anglican Communion's Covenant was adopted as a means of strengthening ties between member churches.

The Catholic Church, in contrast, traces its origins to the establishment of the Church by Jesus Christ in the first century AD. The Council of Nicaea in 325 helped to define the beliefs of the Church, including the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. The Great Schism of 1054 marked the formal split between the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. In the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas's "Summa Theologica" became an influential work of Catholic theology. The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century led to a period of reform within the Catholic Church, culminating in the Council of Trent from 1545 to 1563. The nineteenth century saw the convening of the First Vatican Council in 1869-1870, which defined the doctrine of papal infallibility. The Second Vatican Council, held from 1962 to 1965, brought significant changes to the Catholic Church, including the use of vernacular languages in the liturgy and a renewed emphasis on the role of the laity. In 2014, Pope John Paul II was canonized as a saint.

Catholic and Anglican: A Comparison of Hierarchies, Doctrines, and Practices

The Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion are two of the largest religious organizations in the world. While both are rooted in Christianity and share many similarities, they also have their differences in hierarchy, beliefs, and practices. In this blog post, we will explore some of the key similarities and differences between these two religious organizations.

Hierarchy

The Catholic Church is led by the Pope, who is considered the Bishop of Rome and the spiritual leader of all Catholics around the world. Under the Pope are cardinals, archbishops, bishops, priests, and deacons, each with their own responsibilities and duties within the Church. The Pope has final authority over all matters related to the Church.

On the other hand, the Anglican Communion is led by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is a symbolic leader and does not have the same level of authority as the Pope. Under the Archbishop of Canterbury are archbishops, bishops, priests, and deacons, each with their own responsibilities and duties within the Church. The Anglican Communion operates more independently than the Catholic Church, with provinces having substantial independence in governance.

Doctrines

Both the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion believe in the Holy Trinity, the sacraments, and the person and work of Jesus Christ. However, they differ in some of their beliefs. For example, the Catholic Church believes in papal authority and apostolic succession, while the Anglican Communion believes in the via media, which is a middle way between Catholicism and Protestantism. Additionally, the Catholic Church believes in the doctrine of transubstantiation, which means that the bread and wine used in communion become the actual body and blood of Christ, while the Anglican Communion believes in spiritual presence or may affirm transubstantiation or a symbolic presence.

Practices

Both the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion practice baptism, holy communion, and various forms of prayer. However, they also differ in some of their practices. For example, the Catholic Church practices confession, prayers to saints, and the rosary, while the Anglican Communion practices morning and evening prayer and baptism. Also, the Catholic Church generally requires clerical celibacy for most priests in the Latin Church, while the Anglican Communion does not generally require celibacy.

Comparison of Catholic and Anglican views on Communion

The Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion share many similarities in their beliefs, practices, and traditions. However, there are also some key differences between these two religious organizations. In this blog post, we will explore some of the differences between the Catholic and Anglican views on presence, recipients of communion, frequency of celebration, role of clergy, liturgy and ritual, views on sin and worthiness, and intercommunion with other denominations.

Views on Presence

The Catholic Church believes in transubstantiation, which means that the bread and wine used in communion become the actual body and blood of Christ. While some Catholics may hold other views, such as real presence or spiritual presence, transubstantiation is the doctrine of the Church. On the other hand, the Anglican Communion believes in spiritual presence, with some provinces affirming transubstantiation or a symbolic presence.

Recipients of Communion

The Catholic Church requires that only baptized and confirmed Catholics who are in a state of grace may receive communion. Additionally, they must observe fasting rules before receiving. On the other hand, the Anglican Communion generally allows baptized Christians to receive communion, although policies may vary between provinces and congregations.

Frequency of Celebration

The Catholic Church typically celebrates mass and communion daily, with some exceptions. However, the frequency of celebration may vary between parishes and congregations. The Anglican Communion, on the other hand, may celebrate communion and other liturgical practices weekly or less frequently, depending on the province or congregation.

Role of Clergy

In the Catholic Church, only ordained priests or bishops may consecrate the bread and wine used in communion. Additionally, ordination is required for clergy. In the Anglican Communion, ordained priests or bishops usually consecrate the bread and wine, but some provinces may allow deacons or lay ministers to distribute communion.

Liturgy and Ritual

The Catholic Church follows a standardized liturgy from the Roman Missal, which includes various prayers and practices. On the other hand, the liturgy and ritual of the Anglican Communion may vary between provinces and can be found in the Book of Common Prayer or other authorized texts.

Views on Sin and Worthiness

In the Catholic Church, one must be in a state of grace to receive communion, which may require confession for repentance. However, formal confession is typically not required for those who are conscious of mortal sin. In the Anglican Communion, the approach to sin and worthiness may vary, with emphasis on confession and repentance. However, formal confession is typically not required.

Intercommunion with Other Denominations

The Catholic Church generally does not practice intercommunion with non-Catholic Christian communities. On the other hand, some provinces of the Anglican Communion may practice open communion with other Christian denominations.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the Term "Roman Catholic" | Origin, Usage, and Criticisms

Roman Catholic

The term "Roman Catholic" is often used in official documents to describe members of the Catholic Church, as a way of recognizing those who reject the authority of the Church. Some Anglicans view the Catholic Church as consisting of three main branches: Roman, Anglo, and Greek. However, this view has been shown to be incorrect. For more information on the term "Catholic", please refer to the articles on "church" and "Catholic".

Definition

The "Oxford English Dictionary" defines "Roman Catholic" as follows.

“The use of this composite term in place of the simple Roman, Romanist, or Romish; which had acquired an invidious sense, appears to have arisen in the early years of the seventeenth century. For conciliatory reasons it was employed in the negotiations connected with the Spanish Match (1618-1624) and appears in formal documents relating to this printed by Rushworth (I, 85-89). After that date it was generally adopted as a non-controversial term and has long been the recognized legal and official designation, though in ordinary use Catholic alone is very frequently employed. (New Oxford Dict., VIII, 766)”

Illustrative quotations follow. The earliest is from Edwin Sandys' "Europae Speculum" of 1605: "Some Roman Catholics won't say grace when a Protestant is present." Day's "Festivals" of 1615 contrasts "Roman Catholics" with "good, true Catholics.”

Origin of the Term

The Oxford Dictionary's account of the origin of the term "Roman Catholic" is not entirely satisfactory. The term is actually much older than believed, dating back to the 16th century when English Catholics under persecution defended the lawfulness of attending Protestant services. In response, Protestant divines, such as Father Persons and Robert Crowley, used the term "Roman Catholic" or "Romish Catholic" in their writings. They resented the Roman Catholic Church's claim to the term "Catholic" and insisted that the Reformers were the true Catholic Church. The term "Roman Catholic" originated from this Protestant view, and was used to qualify the term "Catholic" when referring to their opponents. Crowley even referred to his opponents as "Protestant Catholics.”

On the other hand the evidence seems to show that the Catholics of the reign of Elizabeth and James I were by no means willing to admit any other designation for themselves than the unqualified name Catholic. Father Southwell's "Humble Supplication to her Majesty" (1591), though criticized by some as over-adulatory in tone, always uses the simple word. What is more surprising, the same may be said of various addresses to the Crown drafted under the inspiration of the "Appellant" clergy, who were suspected by their opponents of subservience to the government and of minimizing in matters of dogma. This feature is very conspicuous, to take a single example, in "the Protestation of allegiance" drawn up by thirteen missioners, 31 Jan., 1603, in which they renounce all thought of "restoring the Catholic religion by the sword", profess their willingness "to persuade all Catholics to do the same" and conclude by declaring themselves ready on the one hand "to spend their blood in the defence of her Majesty" but on the other "rather to lose their lives than infringe the lawful authority of Christ's Catholic Church" (Tierney-Dodd, III, p. cxc). We find similar language used in Ireland in the negotiations carried on by Tyrone in behalf of his Catholic countrymen. Certain apparent exceptions to this uniformity of practice can be readily explained. To begin with we do find that Catholics not unfrequently use the inverted form of the name "Roman Catholic" and speak of the "Catholic Roman faith" or religion. An early example is to be found in a little controversial tract of 1575 called "a Notable Discourse" where we read for example that the heretics of old "preached that the Pope was Antichriste, shewing themselves verye eloquent in detracting and rayling against the Catholique Romane Church" (p. 64). But this was simply a translation of the phraseology common both in Latin and in the Romance languages "Ecclesia Catholica Romana," or in French "l'Église catholique romaine". It was felt that this inverted form contained no hint of the Protestant contention that the old religion was a spurious variety of true Catholicism or at best the Roman species of a wider genus. Again, when we find Father Persons (e.g. in his "Three Conversions," III, 408) using the term "Roman Catholic", the context shows that he is only adopting the name for the moment as conveniently embodying the contention of his adversaries.

Usage

In a passage from an examination in 1591 (see Cal. State Papers, Dom. Eliz., add., vol. XXXII, p. 322), a deponent was "persuaded to conform to the Roman Catholic faith." However, it's unclear if these are the exact words of the person in question or if they were said to please the examiners. The "Oxford Dictionary" suggests that "Roman Catholic" became the official label for English Papacy supporters during negotiations for the Spanish Match from 1618-24. The religion of the Spanish princess was often referred to as "Roman Catholic" in the various treaties and proposals for this match. Before this period, Catholics were commonly referred to as Papists or Recusants, and their religion was described as popish, Romanish, or Romanist in Acts of Parliament and proclamations. Even after "Roman Catholic" became the official term, it was still used condescendingly. Catholics began to use the term themselves to encourage a friendlier relationship with the authorities, as seen in the "Humble Remonstrance, Acknowledgement, Protestation and Petition of the Roman Catholic Clergy of Ireland" in 1661. The same practice was observed in Maryland. The wish to appease hostile opinions grew greater as Catholic Emancipation became a practical political issue, and by then, Catholics used the qualified term even in their domestic discussions. In 1794, the "Roman Catholic Meeting" was formed to counteract the unorthodox tendencies of the Cisalpine Club, with the approval of the vicars Apostolic. The Irish bishops referred to members of their own communion as "Roman Catholics" during a meeting in 1821. Even Charles Butler, a representative Catholic, used the term "roman-catholic" in his "Historical Memoirs.”

In the mid-19th century, a strong revival of Catholicism led many converts to insist that the name "Catholic" be used without qualification. However, the government refused to allow any changes to the official designation, and even on public occasions, addresses presented to the Sovereign had to use the term "Roman Catholic Archbishop and Bishops in England". Despite attempts to use alternative phrasing, such as "the Cardinal Archbishop and Bishops of the Catholic and Roman Church in England", these were not approved. In 1901, the requirements of the Home Secretary were complied with when the Catholic episcopate presented addresses using the term "Roman Catholics". Cardinal Vaughan explained that this term had two meanings: one that was repudiated and another that was accepted. The term "Roman" is not meant to restrict the Church to a particular species or section, but rather to emphasize its unity and its connection to the Roman See of St. Peter.

Criticisms

Representative Anglican Bishop Andrewes ridiculed the phrase "Ecclesia Catholica Romana" as a contradiction in terms. Catholics make no compromise in the matter of their name as it is the traditional name handed down to them from the time of St. Augustine. Anglicans' dog-in-the-manger policy is brought out in a correspondence on this subject in the London "Saturday Review" (Dec., 1908 to March, 1909).

Source

Catholic Encyclopedia (https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13121a.htm)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History and Beliefs of Anglicanism: A Comprehensive Overview

Anglicanism is the religious belief of the Church of England, and its affiliated churches in the US, British territories, and elsewhere. It includes those who accept the teachings of the English Reformation, as seen in the Church of England and similar offshoots. Anglicanism is primarily found in areas formerly under British control.

Beliefs

To understand Anglicanism as a religious system, let's look at the Established Church of England, keeping in mind that other parts of the Anglican communion may have differences in liturgy and church-government.

Members of the Church of England are Christians who have been baptized and claim to be members of the Church of Christ.

They accept the Authorized Version of the Scriptures as the Word of God.

They believe that the Scriptures are the sole and supreme rule of faith, containing everything necessary for salvation.

They use the Book of Common Prayer as the practical rule of their belief and worship, and hold to the three Creeds as standards of doctrine.

They believe in two sacraments of the Gospel – Baptism and the Lord's Supper – as generally necessary to salvation.

They claim to have Apostolic succession and a validly ordained ministry, and only permit those who are believed to be thus ordained to minister in their churches.

They believe that the Church of England is a true and reformed part or branch of the Catholic Church of Christ.

They maintain that the Church of England is free from all foreign jurisdiction.

They recognize the King as the Supreme Governor of the Church and acknowledge that to him "appertains the government of all estates whether civil or ecclesiastical, in all causes."

The clergy, before being appointed to a benefice or licensed to preach, subscribe to the Thirty-nine Articles, the Book of Common Prayer, and the doctrine of the Church of England as set forth therein, as agreeable to the Word of God.

The Bible can be interpreted in different ways. The Prayer Book's Eucharistic teaching can be interpreted differently. Some think apostolic succession is important, but not essential. Only the Apostles' Creed is required for the laity, and the Articles of Religion are binding only on the licensed and beneficed clergy.

Government

The Church of England's constitution was largely shaped by events during its settlement under the Tudors, within these vague outlines.

Original loyalty to Rome

Before Henry VIII split from Rome, the English Church was part of the Catholic Church under the Pope's jurisdiction. It did not exist as a separate religious system. The name Ecclesia Anglicana was used in the Catholic and Papal sense to represent the region of the one Catholic Church located in England and did not suggest any independence from Rome.

Pope Honorius III, in 1218, in his Bull to King Alexander speaks of the Scottish Church (Ecclesia Scotticana) as "being immediately subject to the Apostolic See."

The abbots and priors of England in their letter to Innocent IV, in 1246, declared that the English Church (Ecclesia Anglicana) is "a special member of the Most Holy Church of Rome."

In 1413 Archbishop Arundel, with the assent of Convocation, affirmed against the Lollards the faith of the English Church in a number of test articles, including the Divine institution of the Papacy and the duty of all Christians to render obedience to it.

In 1521, only thirteen years before the split, John Clerk, the English Ambassador at Rome, was able to assure the Pope in full consistory that England was second to no country in Christendom, "not even to Rome itself", in the "service of God and of the Christian Faith, and in the obedience due to the Most Holy Roman Church."

After the Act of Royal Supremacy (1534)

The first point of separation was due to Erastianism. When the news of the papal decision against divorce reached England, Henry VIII assented to four anti-papal statutes and in November, the statute of the Royal Supremacy declared the King to be Supreme Head of the English Church. The actual ministry of preaching and sacraments was left to the clergy, but all the powers of ecclesiastical jurisdiction were claimed by the sovereign. The chief note of Henrician settlement is the fact that Anglicanism was founded in the acceptance of the Royal, and the rejection of the Papal Supremacy, and was placed upon a decidedly Erastian basis.

When the Act of Royal Supremacy, which had been repealed by Queen Mary, was revived by Elizabeth, it suffered a modification in the sense that the Sovereign was styled "Supreme Governor" instead of "Supreme Head". Elizabeth reasserted the claim made by Henry VIII as to the Authority of the Crown in matters ecclesiastical, and the great religious changes made after her accession were carried out and enforced in a royal visitation commissioned by the royal authority.

In 1628, Charles I declared that it was his duty as king to maintain the Church and promote religious unity and peace. He ordered that differences in the Church's external policy be resolved in Convocation, but their decisions had to be approved by the Crown as long as they did not contradict the laws of the land.

In 1640, Archbishop Laud had canons drawn up in Convocation and published them. However, Parliament was outraged and he withdrew them. The House of Commons unanimously passed a resolution stating that the Clergy in Convocation had no power to create canons or constitutions in matters of doctrine, discipline, or to bind the Clergy and laity of the land without the common consent in Parliament. (Resolution, 16 December, 1640).

The effect of Royal Supremacy

The legislation under Henry VIII was revived by Elizabeth and confirmed in subsequent reigns. As a result, the Crown now has the jurisdiction that was previously held by the Pope before the Reformation. This was highlighted in Lord Campbell's Gorham judgment in April 1850.

Until 1833, the Court of Delegates, a special body appointed by the Crown, exercised supreme jurisdiction. It consisted of lay judges, sometimes with bishops or clergymen. After it was abolished, the King in Council took over its powers. Today, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council advises the King on matters previously handled by the Court. Its decisions, per the statute (2 and 3 William IV, xcii), are final and not subject to review.

This tribunal does not decide on articles of faith or the orthodoxy or heterodoxy of opinions. Its duty is limited to considering the doctrine of the Church of England as established by law and interpreting its Articles and formularies. In 1850, the Crown decided that Mr. Gorham's views on baptismal regeneration were not contrary to the established doctrine of the Church of England, despite protests and appeals from high Churchmen. Similarly, in 1849, when there was vehement opposition to the appointment of Dr. Hampden to the See of Hereford, the Prime Minister insisted on the right of the Crown to nominate, and the Court of Queen's Bench upheld his ruling.

The Anglican Church's spiritual authority has been a topic of debate among its divines. However, the Crown, backed by Parliament and the Law Courts, has practical control over the church's doctrines and those who teach them. After breaking away from Rome, the Crown took over the far-reaching regulative jurisdiction exercised by the Holy See. This authority was never effectively entrusted to the Anglican Spirituality, and there is still no living Church Spiritual Authority in the Anglican Church today. This has been a constant source of weakness, humiliation, and disorder.

In 1904, a commission investigated complaints about ecclesiastical discipline. It issued its report in July 1906, pointing out that laws of public worship have not been uniformly observed in the past. The commission recommended forming a Court that would accept the episcopate on questions of doctrine or ritual, while exercising the Royal Jurisdiction. This would be the first step towards emancipating the Spirituality from the civil power, to which it has been held for over three centuries.

Anglicanism is separate from the doctrine of Royal Supremacy, which is a result of its connection to the State and the circumstances of the English Reformation. Anglican Churches exist outside of England and Wales, where they are said to prosper without state ties. However, even in these countries, the Episcopate does not hold the decisive voice in the Anglican Church. Lay power in synods has shown that it can be a real master. The Anglican system still lacks the supremacy of Spirituality in the domain of doctrine, which is the sole guarantee of true religious liberty. The problem of supplying it remains unsolved, if not insoluble.

Doctrinal and liturgical formularies

The Anglican Church's doctrinal position can only be understood by studying its history. This history can be divided into several periods, including the Henrician period, which established an independent national church and transferred Church authority from the Papacy to the Crown. The Edwardian and Elizabethan periods further separated the Church from Rome and made doctrinal and liturgical changes that defined the Anglican Reformation and placed the nation within the Protestant movement of the sixteenth century.

First period: Henry VIII (1534-1547)

Although Henry VIII's policy after breaking with Rome appeared conservative, aiming to maintain a Catholic Church in England without the Pope, his actions contradicted his professions and were ultimately fatal.

Influence of English Protestant Sympathizers

By raising and maintaining three influential figures, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, and Edward Seymour, all of whom sympathized with the Reformation, Henry VIII paved the way for the rise of Protestantism under Edward and Elizabeth, whether intentionally or as a result of his indifference in his later years.

Henry negotiated with German Reformers in 1535, and in 1537, Cromwell and Cranner negotiated with Protestant princes in Smalkald. Three German divines were sent to London in 1538 to hold conferences with Anglican bishops and clergy. Thirteen articles based on the Lutheran Confession of Augsburg were agreed upon doctrinally, but the King refused to give way on the "Abuses." Although the negotiations formally ended, the Thirteen Articles were kept and eventually formed the nucleus of the Articles of Religion authorized under Edward VI and Elizabeth, showing almost verbal correspondence with the Lutheran Confession of Augsburg.

Second period: Edward VI (1547-1553)

After the death of Henry VIII in 1547, the reformation movement gained momentum under King Edward VI, a Protestant, and with the support of powerful figures like Seymour and Cranmer. During the five-year reign (1547-53), the Reformation party had full national power and introduced significant changes to doctrine and liturgy.

The Reformation brought a cardinal principle of denying the Sacrifice of the Mass. Cranmer upheld this and introduced a new English Communion Service under Edward VI. The Book of Common Prayer, authored by Cranmer, replaced the Latin Mass and was approved by Parliament in 1549. Another Prayer Book was drawn up by the reformers, omitting any mention of Altar or Sacrifice and was authorized by Parliament in 1552. An Order in Council issued to Bishop Ridley required the altars to be torn down, and movable tables substituted in 1551.

A lot of Catholic practices and sacramentals were stopped by Royal Proclamations and episcopal visitations. These practices include lights, incense, holy water, and palms. Cranmer and his followers mainly initiated and quickly carried out these reforms, which reflected their beliefs.

In 1553, a royal decree required bishops and clergy to subscribe to 42 Articles of Religion. These articles incorporated much of what was in the Thirteen Articles agreed upon with the Germans. The article on the Eucharist was changed to align with the teachings of the Swiss reformer, Bullinger.

Third period: Elizabeth I (1558-1603)

In November 1558, Queen Elizabeth replaced Queen Mary and resumed the work of Henry VIII and Edward VI.

The new settlement of religion was based on the more Protestant Prayer Book of 1552, with a few modifications. This version remains substantially unchanged today. The statement that Pius IV offered to approve the Prayer Book has no historical foundation. No contemporary evidence supports it. Camden, the earliest Anglican historian who mentions it, says: "I never could find it in any writing, and I do not believe any writing of it to exist. To gossip with the mop is unworthy of any historian" (History, 59). Fuller describes it as the mere conjecture "of those who love to feign what they cannot find".

The 39 Articles

In 1563, the Edwardian Articles were revised under Archbishop Parker. The number was reduced to 38 and some were added, altered, or dropped. The Articles were ratified by the Queen, and the bishops and clergy were required to assent and subscribe to them. In 1571, the XXIXth Article was inserted, despite the opposition of Bishop Guest, stating that the wicked do not eat the Body of Christ.

During Elizabeth's reign, Anglican teaching and literature leaned towards Calvinism and Puritanism. In 1662, the Prayer Book, which had been suppressed during the Commonwealth, was revised in Convocation and Parliament to emphasize the Episcopal character of Anglicanism against Presbyterianism. The amendments made were numerous, but those of doctrinal significance were few. The most notable were the reinsertion of the Black Rubric and the introduction in the form of the words, "for the office of a Bishop" and "for the office of a Priest", in the Service of Ordination.

Anglican Formularies

The historical and doctrinal significance of the Anglican formularies can only be determined by a thorough examination of the evidence.

1st, study the plain meaning of the text.

2nd, by studying the historical context and circumstances of their framing and authorization;

3rd, by the established beliefs of their main authors and followers.

4th, compared to pre-Reformation Catholic formularies that they replaced.

5th, to understand their teachings better, we need to study their sources and the specific words they used during the controversies of the time.

6th, to avoid narrow-mindedness in examining the English Reformation, one must study the broader Reformation movement in Europe, of which it was a part and result.

Here it is only possible to state the conclusions arising from such an inquiry in briefest outline.

Connection with the parent movement of Reformation

Undoubtedly, the English Reformation is a significant part of the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. Its doctrine, liturgy, and main promoters were heavily influenced by the Lutheran and Calvinistic movements on the Continent.

First Connection: Personal

The key figures of the English Reformation, including Cranmer, Barlow, Hooper, Parker, Grindal, Scory, May, Cox, Coverdale, Peter Martyr, and Martin Bucer, were in close contact and communication with Protestant leaders on the Continent. Conversely, continental reformers such as John a Lasco and Paul Fagius became friends with Cranmer and were welcomed to English universities as professors of Divinity.

Second Connection: Doctrinal

The key ideas of the Protestant Reformation, including doctrines from Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, and Zwingli, are preserved in the literature of the English Reformation. There are nine chief doctrines that are essential and characteristic of the Protestant Reformation as a whole.

rejection of the Papacy,

denial of the **Church Infallibility,

Justification by Faith only,

supremacy and sufficiency of Scripture as Rule of Faith,

The triple Eucharistic tenet includes: (a) considering the Eucharist as a Communion or Sacrament, not a Mass or Sacrifice, except for praise or commemoration purposes; (b) rejecting the idea of Transubstantiation and the worship of the Host; and (c) denying the sacrificial role of the priesthood and the propitiatory nature of the Mass.

the non-necessity of auricular Confession,

the rejection of invoking the Blessed Virgin and the Saints,

rejection of Purgatory and omission of prayers for the dead

rejection of the doctrine of Indulgences.

Three disciplinary characteristics based on doctrine can be added:

the giving of Communion in both kinds;

the substitution of tables for altars; and

the abolition of monastic vows and the celibacy of the clergy.

The twelve doctrines and practices of the continental Reformation influenced the English Reformation to varying degrees. These ideas are reflected in Anglican formularies, and the term "Protestant" is used in the Coronation Service when the King promises to uphold "the Protestant religion as by law established." This term became popularly applied to Anglican beliefs and services. The Act of Union refers to the Churches of England and Ireland as "the Protestant Episcopal Church," a name still used by the Anglican Church in America.

Third Connection: Liturgical

The Anglican Articles were influenced by the Confession of Augsburg and the Confession of Wurtemberg. Parts of the baptismal, marriage, and confirmation services were derived from the "Simplex et Pia Deliberatio" compiled by Lutheran Hermann von Wied with the help of Bucer and Melanchthon. The Anglican ordinal was also influenced by Bucer's "Scripta Anglica", as noted by Canon Travers Smith.

Conclusion

The continental and Anglican Reformations are interwoven in this triple bond of personal, doctrinal, and liturgical aspects, despite their many and notable differences. They form part of one great religious movement.

Use of liturgical reform to deny the Sacrifice

Comparing the Anglican Prayer Book and Ordinal with the Pre-Reformation formularies they replaced reveals that the new liturgy was motivated by the same aim as the Reformation movement as a whole. This aim was to emphasize that the Lord's Supper is a Sacrament or Communion, not a Sacrifice, and to remove any indication of the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist or the Catholic belief in the Real, Objective Presence of Christ in the Host.

The Catholic liturgical forms, missal, breviary, and pontifical were in use for centuries. When making a liturgical reform, changes had to be made with reference to them. Comparing the Sarum Missal, Breviary, and Pontifical with the Anglican Prayer Book and Ordinal reveals the intention of the framers.

The Catholic Pontifical has 24 passages in the Ordination services that clearly express the sacrificial character of the priesthood. None of these were included in the Anglican Ordinal.

The Anglican Communion Service has removed about 25 points from the Ordinary of the Mass that express or imply the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist and the Real Presence of Christ as a Victim. Instead, it has replaced them with passages that are non-committal or have a Reformational character.

The new formularies intentionally exclude sacrificial and sacerdotal elements in 49 places.

(See *The Tablet*, London, 12 June, or 1897.)

Development and parties

Although the Anglican Articles and liturgy have remained largely unchanged since 1662, the life and thought of the Church of England inevitably underwent development. This development eventually outgrew, or at least strained, the historic interpretation of the formularies, due to the lack of a living authority to adapt or readjust them to newer needs or aspirations. The development was guided by three main influences.

Anglicanism's loyalty to the principles of the Reformation has produced the Low Church or Evangelical movement.

Rationalism has induced an aversion to dogmatic, supernatural, or miraculous beliefs, producing the Broad Church or Latitudinarian movement.

Catholicism has influenced Anglicanism through the High Church movement, which put forward higher and philocatholic views on Church authority, belief, and worship.

Oxford Movement

In 1833, a group of Oxford students and writers led by John Henry Newman, including John Keble, C. Marriott, Hurrell Froude, Isaac Williams, Dr. Pusey, and W.G. Ward, defended the Anglican Church against popular opposition. They aimed to establish the Anglican Church's claim to Catholicism, which required looking beyond the Reformation.

The goal was to connect the Anglican Church to Catholic tradition by linking Anglican High Church divines from the 17th and 18th centuries with certain Fathers. This was done through translations of the Fathers, works on liturgy, festivals, and a series of "Tracts for the Times", which conveyed new conceptions of churchmanship.

In "Tract 90", an attempt was made to reconcile the Anglican Articles with the teachings of the Council of Trent, similar to what was done in Sancta Clara. This resulted in a doctrinal and devotional crisis in England, not seen since the Reformation. The Oxford or Tractarian movement, which spanned from Keble's sermon on "National Apostasy" in 1833 to Newman's conversion in 1845, was a significant period in Anglican history. The fact that the movement was informally a study "de Ecclesiâ" brought the writers and readers face to face with the claims of the Church of Rome.

Many who participated in the movement, including its leader, became Catholics. Others who remained Anglicans gave a new direction to Anglican thought and worship with a pro-Catholic perspective. Research into Catholicity and the rule of faith led Newman, Oakley, Wilberforce, Ward, and others to see the need for the living voice of a Divine magisterium (the regula proxima fidei). Failing to find it in the Anglican episcopate, they sought it where it could be found.

Some people looked for guidance from the Church through written texts and definitions, but this approach relied on personal interpretation. This principle still divides people today. Pusey once said that he trusted the English Church and the Fathers, while Newman trusted the bishops, who ultimately failed him.

Anglican revival

The Oxford movement ended with Dr. Newman's conversion in 1845, but many Anglicans were deeply affected by its ideals and did not return to the narrow religious views of the Reformation. Its influence is seen in the continuous conversion of people to the Catholic faith and in the significant change in belief, temperament, and practice within the Anglican Church, known as the Anglican Revival.

Between 1860 and 1910, a growing religious movement emerged in England, seeking to Catholicize the Anglican Church. The movement claims that the Anglican Church is one with the Ancient Catholic Church and offers Anglicans everything except communion with the Holy See. The movement has won favor among many Anglicans by incorporating elements of Catholic teaching and ritual into Anglican services. Despite lacking the learning and logic of the Tractarians, this movement has earned respect and attachment from the masses through the zeal and self-sacrifice of its clergy.

The Anglican Church's advanced section sought to validate its position and overcome its isolation by seeking corporate reunion and recognition of its orders. Pope Leo XIII emphasized the need for dogmatic unity and submission to the authority of the Apostolic See for any reunion to occur. After a thorough investigation, he declared Anglican Orders "utterly null and void" in 1896, requiring all Catholics to accept this as a "fixed, settled, and irrevocable" judgment.

The Anglican Revival appropriates elements of Catholic doctrine, liturgy, and practice, as well as church vestments and furniture, to serve its purposes. The Lambeth judgment of 1891 sanctioned many of its innovations. The Revival believes that no authority in the Church of England can override practices authorized by "Catholic consent". It is a system that aspires to Catholic views while being built upon a Protestant foundation and committed to heresy and heretical communication. Although Catholics view its claims as an impious usurpation of the Catholic Church's rightful domain, the Revival plays an informal role in influencing English public opinion and familiarizing the English with Catholic doctrines and ideals.

Like the Oxford movement, it educates more pupils than it can keep, and is based on premises that will ultimately take it further than it intends to go. Its theories, including a branch theory that is rejected by the main branches, a province theory that is not recognized by other provinces, and a continuity theory that is contradicted by over twelve thousand documents in the Record Office and the Vatican Library, do not provide a stable foundation and are only temporary and transitional. While it may provide an introduction to Catholicism for the masses, it actively undermines and undoes the English Reformation.

Statistics

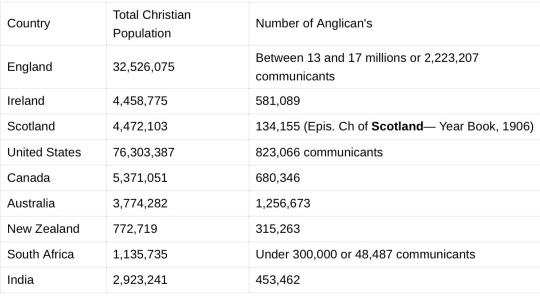

The number of Catholics worldwide was estimated to be over 230 million in 1910, with approximately 100 million belonging to the Greek and Eastern Churches. The number of Anglicans was less than 25 million. Anglicanism is mostly concentrated in England, Ireland, Scotland, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India. However, its membership is a minority of the Christian population in most of these countries, with the exception of England. Anglicanism's foreign missions are generously supported and active in heathen countries.

Sources

Wilkins, Concilia (London, 1737)

Calendar of State Papers: Henry VII (London, 1862 sqq.)

Edward VI (1856 sqq.)

Elizabeth (ibid., 1863 sqq.)

Prothero, Select Statutes

Cardwell, Documentary Annals (Oxford, 1844)

Cranmer, Works

Gairdner, History of the Church of England in the XVIth Century

Dixon, Hist. of Church of England (London, 1878-1902)

Wakeman, Introduct. to Hist. of Church of England (London 1897)

Cardwell, History of Conferences (London, 1849)

Gibson, the Thirty-nine Articles

Browne, Hist. of the Thirty-nine Articles

Keeling, Liturgiae Britannicae

Gasquet and Bishop, Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer (London, 1891)

Dowden, The Workmanship of the Prayer Book

Bulley, Variations of the Communion and Baptismal Offices

Brooke, Privy Council Judgements

Seckendorff, History of Lutheranism

Janssen, History of the German People, V, VI

Original Letters of the Reformation (Parker Series)

Zurich Letters (Cambridge, 1842-43)

Benson, Archbishop Laud (London, 1887)

Church, The Oxford Movement (London and New York, 1891)

Newman, Apologia

Liddon, Life of Pusey (London and New York, 1893-94), III

Benson, Life of Archbishop Benson

#catholic#religion#roman catholic#christianity#roman catholic history#anglican#anglicanism#Anglican Catholic#church

1 note

·

View note