Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Not-Sacramento Athletics

My overwhelming feeling sitting in the stands at Sutter Health Park for two games between the Mariners and Athletics in May was sheer disbelief.

It is unbelievable that Major League Baseball allowed the Athletics—a charter franchise of the American League in 1901, with nine World Series championships in their history—to move to a Triple A ballpark in Sacramento. And not just for one season but for at least three years.

The clubhouses are in center field, there are trees on the berm in right field, and the A’s retired numbers and championship banner look like they were purchased on Amazon. But this is the Athletics' home until they can move to a new ballpark in Las Vegas.

Whether that stadium will be built and whether it will open as scheduled in 2028 are open questions. Until then, the A’s are sharing a home in California’s capital with the Pacific Coast League’s Sacramento River Cats, the Giants’ Triple A affiliate.

As long as the A’s are here, I will try to make this an annual trip. The experience of seeing major league baseball in a minor league stadium is one-of-a-kind. It’s wild that Shohei Ohtani, Aaron Judge, and MLB’s biggest stars will all play in this park during the A’s stay.

For the May series, we bought tickets in advance but were able to take advantage of the Athletics’ disastrous ticket resale market. We found seats 15 rows behind home plate for $40 each, probably a third of what they would cost in other cities.

What jumped out most was the A’s haven’t embraced Sacramento at all. I saw one billboard for the A’s downtown by the Kings arena. The team is wearing a Sacramento jersey patch this season but there was nothing in the team store with Sacramento on it.

Most critically, the A’s asked to be known as just the “Athletics” this season—not the Sacramento Athletics—and the only Sacramento-related souvenirs I could find were a refillable water bottle and soda cup.

The A’s seemingly will not hedge their bets in Sacramento. There’s no suggestion that if fans show up and support the team, Sacramento could be a viable alternative if the Las Vegas plans fall through.

Instead, the A’s are on to their fourth city in franchise history, after moving from Philadelphia to Kansas City to Oakland. The A’s spent 57 seasons in Oakland only to now attempt to follow the NFL’s Raiders to Las Vegas and the dream of a new stadium.

The A’s stopover in Sacramento seems driven by mitigating financial losses more than anything. They were able to retain a significant percentage of their local TV revenues by moving 85 miles up the road. And the A’s attendance will improve after they drew 5,000 or fewer fans 18 times last season.

Even though the A’s made significant upgrades—new clubhouses, new lights, new video board, new field—Sutter Health Park is decidedly minor league. Now 25 years old, the park is not an especially new or nice Triple A stadium.

There’s an enormous “Catch The Excitement” ad board along the third base side for a local casino. We went for ice cream and ended up getting a giant bowl of vanilla soft serve in a drab gray cardboard bowl. That was the quality of the concessions (though they did have Pliny on tap).

With the team clubhouses in center field, the reserves and relievers spent the game shuttling back and forth across the outfield between innings. It was hilarious to watch the team walk in two or three at a time before the game and then head back out when it was over.

On the plus side, the views of the Tower Bridge were pretty at sunset. And we saw two good games, with the Athletics winning 7-6 in 11 innings after Andres Munoz struck out Lawrence Butler, Brent Rooker, and Tyler Soderstrom to escape a bases loaded jam in the 10th.

Julio Rodrigeuz homered the next night and the Mariners scored three runs in the ninth inning to win 5-3, with Cal Raleigh delivering a pinch-hit, two-run single. Attendance at the two games was 10,257 and 9,615, with a surprising number of Mariners fans in the crowd.

There’s no guarantee how long major league baseball will be in Sacramento but the experience was worth the short flight from Seattle. And, besides, it’s not Las Vegas.

* * *

Sam Blum wrote an excellent story for The Athletic on going to see the Athletics in May.

When the majors and minors collide: Buying a ticket and spending a night with the A’s

By Sam Blum

WEST SACRAMENTO, Calif. — It’s been a while since I’ve walked up to a ticket counter at a Major League Baseball stadium.

Then again, that wasn’t really what I did when asking for the cheapest seat inside Sutter Health Park, about 30 minutes before a game last homestand. Because, after all, this isn’t really a big league ballpark. Even if one of MLB’s 30 clubs calls it home for now.

Natural disasters and a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic caused the Tampa Bay Rays and Toronto Blue Jays to play real games in minor-league ballparks over the years. The A’s are spending at least the next three seasons in Sacramento thanks to an entirely man-made catastrophe, resulting in their sharing this 14,000-seat minor-league park with the San Francisco Giants’ Triple-A affiliate, the River Cats, in a city that has mixed emotions regarding their presence.

Plenty has been written and said about the A’s plan to play here for at least the next three seasons, possibly four, possibly more, as their stopover on the way to a hoped-for ballpark in Las Vegas. But I wanted to take in the minor league ballpark experience for myself. Outside the press box. Without the credential. So for the Los Angeles Angels-A’s game on May 21, I walked up and bought a ticket to sit among people doing the same, all with their own perspectives on the matter.

“I don’t like it, I don’t like that they’re here,” said Vince Rivera, a fan walking the concourse in the now-iconic “Sell” shirt. “I live close, but I don’t like it. I would rather be in Oakland. I would rather make the trek out to Oakland. It doesn’t feel right. It’s a minor league stadium.”

So, yeah, there’s no getting around that fact. From a medical cart malfunction when the New York Mets were in town, to Philadelphia Phillies ace Zack Wheeler calling the mound “terrible,” to A’s manager Mark Kotsay not challenging a potential run-scoring play because he couldn’t see down the left field line, this is not exactly the ideal baseball environment.

At the same time, the atmosphere is lively, and, if you take away the ugly dynamics, actually pretty cool. The lawn is full of people spread out like it’s spring training. Kids run around in the playground attached to the ballpark beyond the right field wall. As the national anthem plays and the first pitch is delivered, the brutal heat settles into a calm and comfortable evening as a breeze drifts in off the adjacent Sacramento River. It is Major League Baseball like you’ve never experienced.

But it’s hard to shake the feeling that it’s not like it should be experienced.

“It offers its own unique set of challenges that we’re trying to embrace and deal with as best we can,” said All-Star designated hitter Brent Rooker. “And kind of make the best of the situation over the next three years.”

It didn’t feel like a ringing endorsement.

Still, just like the fans and the players, I resolved to make the best of it. My “seat” cost $25. But it wasn’t really a seat. It was on the outfield lawn. I quickly realized my mistake: I had no blanket, towel or chair. Holding my chicken tenders, fries and a beer — hey, The Athletic said I could expense it — I stood, unprepared as ever.

As the Angels took an early lead, and the A’s quickly took it back, I walked around the park, people-watching, trying to figure out the makeup of this crowd. Were they locals willing to adopt a franchise that refuses to fully identify with its new city? Were these displaced fans from the Bay Area still supporting their team by making the trek? Were they people like me, just captivated by the novelty?

Sometimes you could tell just by looking. A bright white Athletics jersey? Probably a new fan. A clearly broken-in kelly-green Jerry Blevins uniform? Most likely someone who’s been around the block.

Others, you had to talk to to find out.

I asked one season ticket holder, wearing Sacramento A’s shirts, where he and his son had gotten their gear.

Etsy, they said.

That made sense. While perusing the team store, I noticed that only a few items even have “Sacramento” on them. None refer to the team as the “Sacramento A’s.”

That has been a sore spot for the A’s hosts in Sacramento. The Athletics aren’t using the city’s name during their residency here: Instead of being the Sacramento A’s, they’re simply the A’s. Only a measly jersey patch on the sleeve signifies the Sacramento connection, and it’s matched by a Las Vegas patch on the other shoulder, plus “Visit Las Vegas” outfield advertisements that work hard to balance it all out.

Not coincidentally, the 14,014-person venue has regularly had empty seats. A years-long A’s season ticket holder drives from Napa, 90 minutes away, to every home game and back. Her seat is just to the right of home plate, about five rows up, and costs $170 per game. Similar tickets on the secondary market sell for under $100, depending on the game.

“I support the team totally. There’s a lot that’s said, but it’s about (owner John) Fisher. I want to come,” said die-hard fan Joyce Wilson. “… People that are trying to sell, they’re practically having to give them away.”

Therein lies evidence of consternation from potential fans. The demand isn’t matching the supply. A tiny, mostly filled ballpark can mask the issue, make it look like the team is popular. But even my $25 ticket was an overpay. A quick glance on the secondary market that night showed actual seats available for under $20. It’s a small difference that is reflective of a wider issue.

That night it was decently full, with an announced attendance of 10,094, but the home team hadn’t given fans much to be excited about. The Angels jumped on A’s starter J.P. Sears for two runs in each of the second, third and fourth, and by the middle innings the game was getting out of hand. The A’s were facing their eighth straight loss, and it was hard not to feel like their home environment had something to do with it. The clubhouses and batting cages are beyond the outfield wall, and cannot be accessed easily by players. The lack of an upper deck impacts wind and sun patterns. The trappings of the big league lifestyle can only be so replicated.

“The field’s not the best,” said A’s starting pitcher Luis Severino. “The stadium is not the best, or has the accommodations of other stadiums. It’s what we have, we have to be comfortable with what we have. We have a good record on the road versus at home. It’s not easy.

“It’s not what we thought it was going to be, but it’s what we have right now.”

As the game waned, the crowd thinned. It was a long night, and a weeknight, after all. The game went nearly 3 hours and 20 minutes. Only the diehards and the happy Angels fans stuck through until the end. It was in this vacuum that the once-dormant resistance showed itself.

The final season in Oakland was filled with all the vitriol and apathy of a fanbase getting royally screwed over. But on this night, a few “Sell” shirts, and a singular fan yelling “sell the team” twice in between pitches was the only form of protest.

At times, you could almost say the plan worked. It’s not ideal to play in a stadium with a giant River Cats logo atop the ballpark the most visible signage. Some elements of the minor league experience cannot be papered over. But it also just felt like another night at the park.

Then, in the bottom of the eighth inning, the chant started.

“Let’s Go Oakland” filled the humid West Sacramento evening.

I didn’t partake in the chant myself, but I could appreciate the message. I grew up in New York City going to Mets games, loving my team, feeling the loyalty. Heck, I’d spent the first three innings that night following, in pain, as my New York Knicks collapsed in Game 1 of the NBA’s Eastern Conference Finals.

Fandom is a love you embrace, but can’t truly explain. Even in this new city, new park and new existence, fans were still hurting. And being in the thick of it, I could feel it too.

This didn’t seem like it was about the A’s coming back from a three-run deficit. The eventual eighth-straight loss in what would become an 11-game skid was merely a backdrop, secondary to the message.

This was about a fan base that still loves its team, will always love its team, even if it isn’t loved back. The fans feel connected in a way the decision makers that got them to this point have yet to understand.

And in this tiny minor league park, just one person yelling can permeate the stadium and penetrate the television broadcast. This many yelling in unison made for a powerful message.

The A’s left the Coliseum to reset their franchise and get a fresh start. And in that moment, with each passing “Let’s go Oakland” chant, I came to better understand just how far that goal actually is from becoming reality.

0 notes

Text

Samurai Baseball

We visited the shrines and temples of Kyoto, sang karaoke in Shibuya, rode the Shinkansen bullet train, and ate sushi at the Tsukiji fish market. But the highlight for me of our trip to Japan in April was getting to see two games in the most baseball-loving country I could imagine.

For years, I’d wanted to see Nippon Professional Baseball in person, and we made it happen over spring break. Japanese baseball has never been more recognized thanks to Shohei Ohtani, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, and Roki Sasaki, and the energy at the games we went to was off the charts.

Our plan was to see the Hanshin Tigers at historic Koshien Stadium and the Yomiuri Giants—the Yankees of Japan—at Tokyo Dome. Our game at Koshien was rained out, but we ended up enjoying an unforgettable game with the Chiba Lotte Marines as a result.

Nothing will top our 2025 baseball trip. And if I owned an MLB team, the first thing I would do is try to make it more like Japanese baseball.

* * *

Koshien is the Wrigley Field of Japan and hosts the annual national high school baseball tournament. It opened in 1924 and is one of only four ballparks remaining where Babe Ruth once played (along with Wrigley, Fenway Park, and Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Stadium).

Ruth and a team of American stars played at Koshien as part of their historic 1934 tour of Japan, and there’s a plaque of Ruth just outside the stadium. According to reports, over 500,000 Japanese came out to greet Ruth and the Americans when they arrived in Tokyo to start the tour.

We made it inside Koshien only to wait out an hour-long rain delay before they canceled the game. Unfortunately, they never pulled the tarp so we couldn’t see the all-dirt infield. But we walked around the park and got a feel for Koshien and its ivy-covered walls and history.

* * *

I think the rainout happened for a reason because we wouldn’t have gone to Chiba otherwise. Back in Tokyo, and determined to see two NPB games on the trip, my son and I took a 40-minute ride east to see the Marines at their stadium along Tokyo Bay.

The Marines are a second-tier NPB team (they’re currently last in the Pacific League) but we had an unforgettable night. We saw Ohtani’s former team (the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters) beat Sasaki’s former team (the Marines) 9-3 behind an eight-run sixth inning.

Even before we made it inside ZOZO Marine Stadium, I realized we were in for something special. I’ve seen a lot of mascots and dance teams but nothing like Chiba Lotte, who put on a zany pop-punk routine that I still watch whenever I’m a little down.

The Marines stadium feels like Comiskey Park in the 1990s and the blustery conditions didn’t help. But we had great seats close to home plate and my son got a foul ball in the top of the first inning—the ultimate NPB souvenir among all the hats and jerseys we brought back.

Chiba Lotte felt like the true Japanese baseball experience, with only a handful of other Americans at the game. And we marveled at the uniqueness. The managers and umpires bowed before exchanging lineup cards at home plate. Relief pitchers were driven out in the back of a Mercedes convertible. Players stayed loose between innings by playing catch outside their dugouts, even while their team was batting. Ubiquitous beer girls in neon shirts ran around the stadium pouring Asahi and Sapporo.

Most remarkable were the cheering sections. Even on a Tuesday night in April, the Fighters’ and Marines’ fans chanted non-stop from their respective outfield sections. Each player had his own cheers, including a fantastic “El Coffee” cheer for Gregory Polanco from the Dominican Republic, who hit a mammoth homer for Chiba Lotte in the second inning.

As loud as the fans were, the cheering sections were also highly respectful, with each team’s fans sitting while the other team was at bat. The chanting made it feel more like a soccer match than a baseball game. You realize how lame the wave is at MLB games after watching the fans in Japan cheer all night (and I don’t think the best fans in baseball are in St. Louis any longer).

My son said on the ride back to Tokyo that it was the most fun he’d ever had at a baseball game. I agreed. We will always be Chiba Lotte fans thanks to that game.

* * *

Two days later, we went as a family to see the Giants and Yokohama DeNA BayStars at the Tokyo Dome. It was surreal to be in the Big Egg less than a month after the Dodgers and Cubs opened the MLB season in Japan. Those games felt so far away on TV … and then we were there in the stands.

Tokyo Dome is home to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, which my son and I visited in the afternoon. The 2023 World Baseball Classic championship trophy was on display, along with Sadaharu Oh’s 800th home run bat and balls from Ohtani’s first and last NPB games.

Not surprisingly, the Japanese Hall has a great collection of Ichiro and Ohtani jerseys. And the plaque gallery felt a lot like Cooperstown. There are even now two foreign players enshrined in the Japanese Hall, with former NPB stars Randy Bass and Alex Ramirez inducted in 2023.

The Tokyo Dome experience was the complete opposite of Chiba Lotte. We ate at Shake Shack after finishing at the Japanese Hall and rode the Thunder Dolphin roller coaster at the next door amusement park before heading into the stadium.

The Giants merchandise is all Nike and New Era as they were the first NPB team to partner with Fanatics. There were a shocking number of Americans among the sellout crowd of 41,767. And the Tokyo Dome felt like the old Metrodome in Minneapolis. If not for the cheering sections and beer girls, we could have been at an MLB game.

We got to see former Yankees pitcher Masahiro Tanaka, who is finishing his career with the Giants and was bidding for his 200th career win across MLB and NPB. We bought No. 11 Tanaka jerseys, but the 36-year-old made it through just two innings and gave up seven hits and six runs.

With the Giants down 7-0 after three innings, we sampled some dumplings and enjoyed Big Egg ice cream sandwiches. Katsuki Azuma struck out 10 in eight shutout innings for Yokohama and former major leaguer Kyle Keller pitched an inning of relief for the Giants in the 9-1 loss.

We’ll see baseball in Japan again someday. It was too much fun not to go back. In the meantime, I’m looking forward to watching Ohtani’s homecoming with Samurai Japan in the 2026 World Baseball Classic—and picturing myself back in our seats at Tokyo Dome.

* * *

A handful of other thoughts on the Japanese baseball experience:

You don’t realize how much the pitch clock saved MLB until you go to an NPB game with no clock. Both games we went to were over three hours long.

You also don’t realize how easy the American ticket-buying experience is until you try to get tickets to an NPB game. Tickets for Hanshin and Yomiuri were a challenge even going early in the season in April. We worked for months with a broker but ended up having to buy tickets for Chiba Lotte and Yomiuri off StubHub (which is not recommended) and thankfully did not have any issues. Even after buying tickets, we still had to print them at a convenience store the day of the games.

I thought the food would be a highlight but it was just a challenge. Many of the concession stands offer bento boxes or food items that are identified with individual players (an American player might be pictured with the cheeseburger meal). At Chiba Lotte, we were hungry and enjoyed some delicious rice bowls, but I have no idea what was in them. The dumplings at Tokyo Dome were good (and it was fun to eat with chopsticks at a baseball game) but nothing really stood out.

NPB teams are allowed to have up to four foreign players on their roster. Polanco, Franmil Reyes, and Elier Hernandez were the star imports for the Marines, Fighters, and Giants.

We found a baseball card store at a mall in Shibuya and bought some packs of Topps NPB cards, which were pretty cool.

You could see a lot of NPB without venturing much out of Tokyo. Five of the 12 teams are located within an hour of Tokyo (the Giants, Marines, and BayStars, along with the Tokyo Yakult Swallows and Saitama Seibu Lions).

Ohtani is everywhere. The first thing you see getting off the plane at Haneda Airport is an Ohtani ad. He endorses Kose cosmetic products, Seiko watches, Ito En green tea, Secom security services, New Balance, and Hugo Boss. There were five Ohtani billboards for different companies around Shibuya Scramble. According to a story in the Japan Times, rice ball sales increased 120 percent when the Family Mart convenience store launched a campaign with Ohtani.

The 7 p.m. NPB games that we went to started at the equivalent of 3 a.m. Pacific. I’ve been able to watch some Saturday and Sunday afternoon games in Japan on Friday and Saturday night on the West Coast. There’s a streamer called Dingo TV that broadcasts NPB Pacific League games live.

* * *

I really appreciated the New York Times’ obituary for Shigeo Nagashima, Japan’s Mr. Baseball, when he died in June. It told a lot about the history of baseball in Japan in this remembrance of one of its biggest stars.

Shigeo Nagashima, ‘Mr. Baseball’ of Postwar Japan, Dies at 89

By Ken Belson

Shigeo Nagashima, Japan’s most celebrated baseball player and a linchpin of the storied Tokyo Yomiuri Giants dynasty of the 1960s and 1970s, died on Tuesday in Tokyo. He was 89.

His death, in a hospital was attributed to pneumonia, according to a joint statement released by the Giants, the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper and Nagashima’s management company.

A star from the moment he signed his first professional contract in 1957, Nagashima instantly made a splash with his powerful bat, speed on the basepaths and catlike reflexes as a third baseman. He notched numerous batting titles and Most Valuable Player Awards, and he was a key member of the Giants’ heralded “V-9” teams, which won nine consecutive Japan Series titles from 1965 to 1973. More than any player of his generation, Nagashima symbolized a country that was feverishly rebuilding after World War II and gaining clout as an economic power. Visiting dignitaries sought his company. His good looks and charisma helped make him an attraction; he was considered Japan’s most eligible bachelor until his wedding in 1965, which was broadcast nationally.

The news media tracked Nagashima’s every move. The fact that he played for the Giants, who were owned by the Yomiuri media empire, amplified his exploits. He wore his success and celebrity so comfortably that he became known as “Mr. Giants,” “Mr. Baseball” or sometimes simply “Mister.”

“No matter what he did or where he went there was a photo of him — attending a reception for the emperor, or coaching a Little League seminar, or appearing at the premiere of the latest Tom Cruise movie,” Robert Whiting, a longtime chronicler of Japanese baseball, wrote about Nagashima in The Japan Times in 2013. “People joked that he was the real head of state.”

None of that celebrity would have been possible had he not excelled as a ballplayer. Along with his teammate Sadaharu Oh, Japan’s home run king, Nagashima was the centerpiece of the country’s most enduring sports dynasty. He hit 444 home runs, had a lifetime batting average of .305, won six batting titles and five times led the league in runs batted in. He was a five-time most valuable player and was chosen as the league’s top third baseman in each of his 17 seasons. He was inducted into Japan’s Baseball Hall of Fame in 1988.

In his first season, 1958, he led the league in home runs and was second in stolen bases and batting average, earning him rookie of the year honors. And then, early in his second season, he made history in the first game attended by a Japanese emperor, Hirohito, and an empress, Nagako. In the bottom of the ninth inning, Nagashima blasted a 2-2 pitch into the left field stands for a game-winning home run, considered one of the most dramatic sports events in Japanese history.

One of Nagashima’s trademarks was his work ethic, a character trait that was particularly celebrated during Japan’s postwar rise. Under the guidance of manager Tetsuharu Kawakami, Nagashima practiced from dawn to dusk, enduring an infamous 1,000-fungo drill, which required him to field ground ball after ground ball. In the off-season, he trained in the mountains, running and swinging the bat to the point of exhaustion. He bought a house by the Tama River in Tokyo so that he could run there, and he added a room to his home where he could practice swinging.

He was often the Giants’ highest-paid player, showered with hefty contracts and bonuses. By the early 1960s, word of his talents had reached the United States. Bill Veeck of the Chicago White Sox tried unsuccessfully to buy Nagashima’s contract, as did Walter O’Malley of the Los Angeles Dodgers, now home to the Japanese superstar Shohei Ohtani. (Ohtani offered his condolences on Instagram, posting photos of himself with the aging Nagashima.)

After ending his playing career in 1974 (his number, 3, was retired), Nagashima became the team’s manager at just 38. He was far less successful in that role, at least at first. He pushed his players — some of whom were his former teammates — to work as hard as he did. “Bashing the players this year cultivates spirit,” he told The Japan Times.

In his first season, the Giants finished in last place for the first time. The next two years, they won the Central League pennant but lost the Japan Series. The Giants failed to win their division for the next three years, and Nagashima was let go in 1980. Shigeo Nagashima was born on Feb. 20, 1936, in Sakura, in coastal Chiba prefecture, east of Tokyo. His father, Toshi, was a municipal worker, and his mother, Chiyo, was a homemaker. Nagashima grew up rooting for the Hanshin Tigers, the Giants’ archrival. He took up baseball in elementary school, but because of wartime shortages, he made a ball from marbles and cloth and used a bamboo stick as a bat. After graduating from high school, he entered Rikkyo University in Tokyo, where he started at third base. Rikkyo, typically an also-ran, won three college tournaments.

After graduating, Nagashima signed a then-record 18 million yen contract (about $50,000 in 1958, or about $550,000 in today’s money) with the Giants. As his star rose on the field, speculation about his marital status grew. In 1964, he met Akiko Nishimura, a hostess at the Tokyo Olympic Games that year. She had studied in the United States and spoke fluent English, which were considered marks of status and education. Their wedding was the most-watched television broadcast in Japan the following year. She died in 2007.

Their oldest child, Kazushige, played sparingly for the Giants when his father managed the club; he now works in television. Nagashima’s second son, Masaoki, is a former racecar driver, and his daughter, Mina, is a newscaster. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

After Nagashima’s first stint as a manager, he worked as a television commentator. His affable style was matched by his occasionally incomprehensible chatter. But his charisma made him an irresistible target when the Giants were looking for a new manager in 1993. Then 56, Nagashima debated whether to return to the dugout.

“My wife and I were looking forward to a quiet life playing golf, and it was hard to decide to throw myself back into the fight,” he told reporters. “But I was raised as a Giant, and if I have the strength, I will do whatever it takes for the Giants.”

Mellowed by age, Nagashima was easier on his players this time around. He also had the good fortune to manage Hideki Matsui, the team’s cleanup hitter and one of the most fearsome sluggers of the 1990s. (He joined the Yankees in 2003.) The Giants won two Japan Series titles, in 1994 and 2000, during Nagashima’s nine-year tenure. In his 15 years as a manager, his teams won 1,034 games, lost 889 and tied 59 times. The Giants made him a lifetime honorary manager.

As he was preparing to manage the Japanese team at the Olympic Games in Athens in 2004, Nagashima, then 68, suffered a stroke that partly paralyzed his right side. Though he was seen less in public in the following years, he was no less adored. In 2013, he and Matsui were given the People’s Honor Award by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Eight years later, they were torch bearers at the opening ceremony at the Tokyo Games. Matsui walked slowly, holding Nagashima, as his old teammate, Oh, held the Olympic torch.

0 notes

Text

The Home-Away-From-Home Team

If you told me when I went to spring training in February 2020 that I would be watching a seven-inning doubleheader in Buffalo, N.Y., featuring the Texas Rangers and Toronto Blue Jays in July 2021 … well, I certainly would have had some questions.

Now? It all makes sense after COVID-19 wreaked havoc on the world and Major League Baseball, reducing the 2020 season to just 60 games. But 17 months ago? I would not have believed that Buffalo would soon be hosting MLB games.

After all, in the last century, Buffalo’s greatest claim to baseball fame was as the location where “The Natural” was filmed at old War Memorial Stadium, with sparks raining down on Roy Hobbs as he circled the bases after his immortal home run.

Otherwise, Buffalo was last home to a Federal League team in 1914 and 1915. And before that, the Buffalo Bisons (featuring Hall of Famers Pud Galvin, Dan Brouthers, and Deacon White) played in the National League between 1879 and 1885.

That’s why this year’s baseball trip had to be to Buffalo. What better represents the last two years of pandemic baseball than seeing the exiled Blue Jays playing home games at Triple A Sahlen Field—less than five miles from Canada, yet so far from returning?

I followed the back and forth for weeks over the Blue Jays’ request to the Canadian government to return to Toronto. The Blue Jays played their last 26 games of the 2020 season in Buffalo with the border closed and then opened the 2021 season at their spring training home in Dunedin, Fla.

They returned to Buffalo for a series against the Miami Marlins beginning June 1, 2021. Unlike in 2020, local fans were able to attend this season’s games at Sahlen Field.

Finally, on July 16, the Blue Jays received permission to return to Rogers Centre for a 10-game homestand beginning in two weeks on July 30. That left six games to say goodbye to Buffalo. And I was determined to make it before the Blue Jays left.

I booked the trip at the last minute—a flight from Seattle to Pittsburgh, then a 3½-hour drive to Buffalo. After their July 17 game was rained out, the Blue Jays played a seven-inning Sunday afternoon doubleheader against the Rangers on July 18.

The Blue Jays clobbered Texas by a combined score of 15-0 over the two games—5-0 in Game 1 as Hyun Jin Ryu pitched a shutout and 10-0 in Game 2 as Lourdes Gurriel Jr. hit a grand slam for one of Toronto’s (Buffalo’s?) four homers off Mike Foltynewicz.

Even with the blowouts, it was one of my favorite baseball experiences ever. To watch a big league game (two of them) in a city that hasn’t had a team in 106 years was wonderful. And a major-league game played in a Triple A park felt like seeing a big-name band play a club show.

The amount of work that went into hosting 49 games over two seasons in Buffalo was easily apparent. Whether it was the Blue Jays, MLB, or the Triple A Buffalo Bisons, millions of dollars were clearly spent.

The Bisons (a Blue Jays affiliate) relocated to Trenton, N.J., so Toronto could move in. The Blue Jays plastered Sahlen Field with “Home of the Blue Jays” signage—from the stadium gates to the signs along the concourse (which directed fans to the very Canadian “washrooms”).

They constructed an entire visiting team clubhouse and other facilities in temporary tents in center field. They also renovated the home clubhouse and turned the Triple A visiting clubhouse into Blue Jays’ coaches’ offices.

The Blue Jays also replaced all of the stadium lights and brought the field up to major league standard. You don’t think about the drainage necessary for a major league stadium until it rains 3 inches in a day (which led to the doubleheader).

For what it’s worth, the seven-inning doubleheader, intended to reduce time at the ballpark for teams amid COVID-19, created a game with minimal rhythm. It seemed like everyone double-checked to make sure the game was really over after the last out.

The first game took just 1 hour 48 minutes, while the second game was three minutes longer. And for the record, they sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” as part of a fifth-inning stretch during the seven-inning doubleheader.

As for the park, Sahlen Field opened in 1988 and preceded even Camden Yards in the trend of retro downtown stadiums. Originally named Pilot Field, the stadium was built in the hopes of Buffalo landing an MLB expansion team, which went to Florida and Colorado in 1993.

The park is starting to show its age after 33 years—it is not comparable to the Triple A stadium built in Reno, Nev., that opened in 2009--but it felt like the Blue Jays’ home with all of the signage and upgrades, as opposed to just temporary housing.

The doubleheader drew 12,335, the largest crowd of the season to date in Buffalo, which was eclipsed the very next night when the Blue Jays hosted the opener of their last three-game series at Sahlen Field against the Red Sox.

There were long lines to get into the Blue Jays’ temporary team store—the Bisons’ store was nowhere near large enough—and the concourse was jammed between games of the doubleheader.

For the record, the Blue Jays averaged 7,733 fans for their 22 home dates in Buffalo for the 2021 season, better than three major-league teams (Tampa Bay, Oakland, and Miami).

If you tuned in on TV, you would have thought the game was played in Canada. The advertisements on the outfield wall and behind home plate were distinctly Canadian (Pizza Nova? Home Hardware? MNP? Sobeys?) and looked like Rogers Centre.

They played both the Canadian and U.S. anthems before first pitch. I had a Labatt Blue Light, though I think that’s a staple at Sahlen Field even without the Blue Jays. Beyond left field was a sign for I-190 North heading to the Peace Bridge and Niagara Falls.

My one disappointment was how little Buffalo color there was, despite the game being played in the city’s downtown. After receiving permission from the Canadian government to return, the Blue Jays did put “Thank you Buffalo” signs on the two dugouts.

But there were no advertisements for Buffalo car dealers or banks or personal injury attorneys or any of the staples of ballparks across the country. Other than the stadium being Sahlen Field—and I enjoyed a Sahlen hot dog during Game 2—it didn’t feel like Buffalo.

There was one exception. Rangers catcher Jonah Heim grew up in Amherst, N.Y., and became the first Buffalo native to play a major-league game in the city since John Gillespie played for the Buffalo Bisons in the short-lived Players League in October 1890.

Heim singled off Steven Matz in Game 2 and got a huge ovation from the crowd. You wondered how many fans knew Heim (I saw a couple of jerseys and shirts) and how many were just acknowledging the hometown kid. But it was a true Buffalo baseball moment.

There was also a great fact noted in The Buffalo News: With the Blue Jays’ temporary relocation, Buffalo became one of just 15 cities to host big-league baseball teams in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Who knows what the 2100s will bring for Buffalo baseball?

Ultimately, if the mission was to provide a home away from home for the Blue Jays—with close-to-major-league facilities for the players and a Toronto feel for the television broadcasts—then Buffalo more than delivered.

I was so glad to make it with three days to spare, to watch MLB games in a city that I could not have imagined just two years ago.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Green Day

Every year I look forward to the photos from spring training of teams decked out in their St. Patrick’s Day jerseys and caps. I’m also more than a little jealous of the fans in attendance—not only are they enjoying baseball in the sun, they’re witnessing one of the sport’s great traditions.

This year I finally got to be that fan. A work trip took me to Arizona in the middle of spring training and I stuck around an extra day to catch the Indians and Reds in Goodyear. And, as they first did over 40 years ago, the Reds turned into the Greens to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.

The Reds became the first team to wear green on St. Patrick’s Day in 1978 for a game against the Yankees. The players apparently had no advance notice and were surprised with the jerseys an hour before game time. A New York Times story from the game noted that the green jerseys were completely out of character for the Reds, who didn’t even wear stripes on their shoes.

Sparky Anderson, then the Reds manager, said of the uniforms: “That’s what people don’t understand. We’re not as old‐fashioned as people think. We can have fun, too. The Yankees will have to come up with another idea to upstage us. Steinbrenner won’t know what to do.”

The Yankees lost 9-2 to the Reds in that 1978 game. For his part, George Steinbrenner was quoted in the same story as saying: “I think the green uniforms matched my complexion after seeing the inadequacies of the team that is supposed to be world champion.”

What started with the Reds is now entrenched across baseball. MLB has a complete St. Patrick’s Day apparel collection for every team. The St. Patrick’s Day caps this year (for almost every team) were white with green bills and logos and a shamrock accent on the crown.

Some teams opt to wear their regular spring training jerseys with the caps (as the Indians did). My favorite St. Patrick’s Day look is similar to what the Reds did in 1978, with teams wearing their home white uniforms but changing the color of their logos, numbers, and striping to green.

The Reds opted for such a look last season, along with a “First Team to Wear Green” commemorative patch on the 40th anniversary of that 1978 game. This year, the Reds went with green jerseys and white lettering. They still looked great.

The game itself was terrific. With the bases loaded in the fourth inning, Yasiel Puig came up against former Cy Young winner Corey Kluber and crushed a grand slam to erase a 3-0 Cleveland lead. Everyone knew Puig would swing for the fences and yet he still connected.

Puig homered a second time in the fifth inning before leaving with the rest of the starters in the seventh. The Indians then staged a four-run comeback in the ninth inning and the game ended in a 9-9 tie. Given that the Reds and Indians share Goodyear, both teams’ fans went home happy.

Between the postcard-perfect afternoon (76 degrees at first pitch), Puig’s electrifying grand slam, and the green jerseys, it was about as good as spring training gets.

It also was my first game at Goodyear Ballpark, which is located 20 miles west of downtown Phoenix. The St. Patrick’s Day game was the 10th anniversary celebration of the Goodyear facility, which is almost shocking as it feels like Goodyear opened yesterday.

It’s hard to believe Goodyear has been around for 10 years considering how new the stadium feels and the fact that there’s still almost nothing around it. You see the ads on the outfield wall and in the program for supposedly nearby businesses and you wonder where they are.

There is nothing on the drive from Interstate 10 to the ballpark other than a nearby airport boneyard for planes no longer used. I found myself wondering where the Indians and Reds players live during spring training when there’s so little around the park.

Goodyear does have a great baseball sculpture in front of the stadium, and the park was very comfortable. I highly recommend the shaded club seats behind third base; they have attendants to deliver food and drinks, which helped on a crowded afternoon with endless lines.

There is a nice tribute to Frank Robinson, whose number 20 was retired by both the Reds and Indians, in left field. Goodyear had bounce houses and wiffle ball fields for the kids. It looked like you could get Skyline chili at one of the concession stands, but I couldn’t manage the line.

Goodyear wouldn’t be on my must-see list of spring training parks. But St. Patrick’s Day with the Reds was something special.

0 notes

Text

K.C. Masterpiece

After graduating college in 2002, I packed up my car and ventured into the real world, starting with a road trip from Chicago to San Francisco. My now-wife came along too, though she was moving to New York for an internship. Those were anxious days—I didn’t have a job and wouldn’t for several months—but they also were memorable and special.

As part of the trip, we stopped in Kansas City and caught a Royals game at Kauffman Stadium. Neither my wife nor I remember much about the game, other than the famous fountains and that it was so hot it felt like being in a furnace. I went on to see games at all 30 major-league stadiums, but that afternoon was my first and only game in Kansas City.

Thanks to Baseball-Reference.com, I can see why that June 27, 2002, game was so forgettable. Both the Royals and Detroit Tigers went on to lose 100 games that season. The Royals won 5-2. Paul Byrd earned the win, Mike Sweeney homered, and Roberto Hernandez saved it. There were 16,373 in attendance. And it was 88 degrees at first pitch.

Sixteen years later, I made it back to Kauffman Stadium on this year’s baseball trip. I saw two games of the Royals’ series against Shohei Ohtani, Mike Trout, and the Angels. The weather couldn’t have been more different—it was 42 degrees at first pitch on April 14 and snowed from the fifth inning on (see above photo). I’ve been to hundreds of games over the years—including several frigid April games in Chicago—but never before a snow game.

Kauffman Stadium was the draw (along with seeing Ohtani 10 games into his career) and it far exceeded my memories and expectations. The fountains remain the featured attraction, but the stadium underwent a $250 million renovation in 2008 and is one of the jewels of the majors.

I enjoyed Kauffman Stadium more than any park I’ve been to in recent years. Were it not located in a giant parking lot next to Arrowhead Stadium and Interstate 70—and were the concession stands a little more distinctive for such a great food city—I would probably rate Kauffman Stadium as a top-five ballpark.

There was a lot to love about the Royals’ home, which is the sixth-oldest park in the majors (opening in 1973) and the lone baseball-only stadium built between 1966 and 1991.

For starters, the fountains are such a unique feature, and the Royals actually sell bottles of “Fountain Water” for $10 at their team store. I didn’t realize it until the trip, but Kansas City is dubbed the City of Fountains and boasts having more fountains than Rome (and more boulevards than Paris). I stood in the outfield in the late innings one night just to watch the fountains between innings.

The Royals also have perhaps the best Hall of Fame of any team. The facility was built in left field as part of the recent renovations. The memorabilia on display is extraordinary—everything from the ball from George Brett’s first major league hit (he totaled 3,154) to Frank White’s eight Gold Gloves to the last out ball of the 2015 World Series to the Royals’ two Commissioner’s Trophies. The Hall is open before and during games until the eighth inning.

The Royals additionally have the greatest scoreboard in the majors—a 12-story HD board shaped like the Royals logo and topped by a crown. The scoreboard towers over the outfield and creates a majestic panorama looking out from home plate. The picture quality is not necessarily the sharpest, but there’s no scoreboard like it in baseball.

I also was fond of a lot of the little touches at Kauffman Stadium. They sell boxes of baseball cards from the 1980s and 1990s in the team store. They have a five-hole putt-putt course in the outfield as part of a kids’ area. They have probably the best selection of game-used memorabilia I’ve seen (I bought a ball to add to my collection). They have dedicated Boulevard Brewing bars throughout the stadium.

Parking is $15 a car, and there doesn’t seem to be a great alternative for getting to Kauffman Stadium, which is about 15 minutes from downtown. On the other hand, thanks to the Royals’ 3-9 start and the freezing weather, I bought a ticket five rows behind the Kansas City dugout for $22 on StubHub.

I’ve seen a lot of small crowds at Safeco Field since moving to Seattle and adopting the Mariners, but it was a little alarming to see the Royals announce crowds of 15,011 and 15,876 for Friday and Saturday night games, which should be far stronger draws.

As far as the games, I saw the Angels rally to win 5-4 on April 13. Albert Pujols blasted his 617th career home run and later singled off Brad Keller in the seventh to drive in a run and start the Angels’ comeback. (Bad feet and all, Pujols also slid into first base trying to beat out Alcides Escobar’s high throw on a ground ball to short in the game.) The home run and single were the 2,986th and 2,987th hits of Pujols’ career.

Ohtani batted seventh as the designated hitter and went 2-for-4 to raise his average to .367 (and his OPS to a ridiculous 1.191). In the second inning, Ohtani looked completely late swinging at Jason Hammel’s fastball, then managed to turn on a two-strike pitch and double into the left field corner. He also singled in the eighth and scored the winning run on Ian Kinsler’s sacrifice fly.

The Angels won the following night as well, 5-3, in the most miserable conditions I think I’ve experienced. The umpires were determined to get in the game despite the rain and the snow. Garrett Richards started for the Angels and threw four perfect innings before losing his control in the rain and cold. Richards walked two and threw three wild pitches in the fifth but escaped with a 4-1 lead thanks to an inning-ending double play.

The best moment came in the top of the fifth with Trout at the plate and the rain falling hard. Trout crushed a 429-foot homer to left field off Jakob Junis to make it 4-0. It was Trout’s sixth home run of the season and might have been the most impressive blast I’ve ever seen given the weather. Trout has 207 career homers and won’t even turn 27 until August.

I made it until the eighth inning with the snow falling before needing to get warm. Those final innings were a struggle, but it also was fitting to see Kauffman Stadium—such a wonderful ballpark—turned into a one-night snow globe.

0 notes

Text

Division Game

Let’s start with what the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., isn’t.

It’s not a hall of fame for Negro Leagues players and executives. There are currently 35 former Negro League players and executives enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., immortalized (as they should be) alongside Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, and the other major-league greats.

On this point, the NLBM makes its position abundantly clear: “Often the museum is referred to as the ‘Negro Leagues Hall of Fame’ or ‘Black Baseball Hall of Fame’ and various names. It is important to the museum that we not be referred to as such. The NLBM was conceived as a museum to tell the complete story of Negro Leagues Baseball, from the average players to the superstars.

“We feel VERY strongly that the National Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, NY, is the proper place for recognition [of] baseball’s greatest players. The Negro Leagues existed in the face of segregation. Baseball’s shrines should not be segregated today. Therefore, the NLBM does not hold any special induction ceremonies for honorees. As space allows, we include information on every player, executive, and important figure. However, we do give special recognition in our exhibit to those Negro Leaguers who have been honored in Cooperstown.”

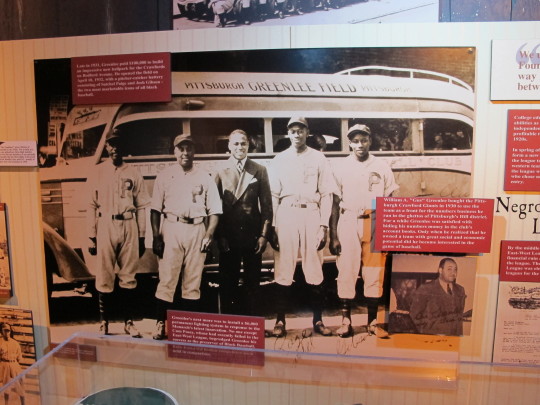

As compared to Cooperstown, though, the NLBM is the place where the story of the Negro Leagues is most completely told. The museum, which was founded in 1990 and moved into its current space in the 18th and Vine district of Kansas City (a historic center of African-American culture) seven years later, features a chronological history of African-American baseball from the 1860s until the death of the Negro Leagues in the 1960 following integration in MLB.

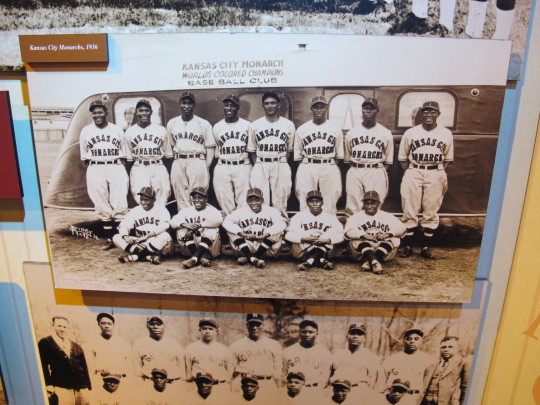

I visited the museum on this year’s baseball trip and came away with a far greater appreciation for Negro League history. The Negro Leagues were pioneering in many respects: For one thing, I didn’t know that night baseball was first played by the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues in 1930, five years before the first major-league game under the lights.

I also was not aware of the organizational struggles of Negro League teams. The NLBM proudly displays the articles of incorporation of the first Negro National League in 1920. But the league, which was founded at a Kansas City YMCA, existed only until 1931, far before what the museum describes as the Negro Leagues’ heyday in the 1940s.

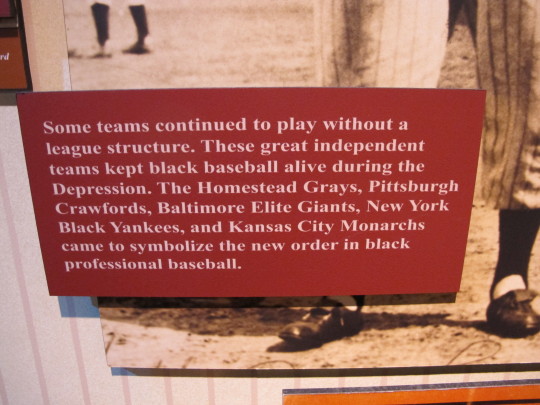

As well known as several Negro League teams are today—the Monarchs, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords (with Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, and Cool Papa Bell), and Newark Eagles—the teams struggled mightily as businesses. According to the NLBM, the Grays were the only profitable team in the 1920s.

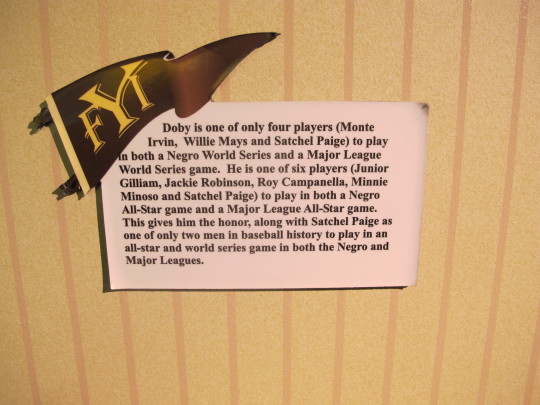

There were numerous interesting facts among the NLBM exhibits. Satchel Paige was the biggest star and highest-paid Negro Leaguer, barnstormed across the country, and would not hesitate to change teams for a bigger payday. The annual East-West All-Star Game drew crowds of 50,000-plus at Comiskey Park in the early 1940s. Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, Willie Mays, and Paige all played in both the World Series and Negro League World Series. Paige was the oldest rookie in MLB history and was an All-Star at age 45 and 46.

My only criticism of the NLBM would be that it perhaps focuses too much on the Negro League owners and organizers, though Gus Greenlee, Rube Foster, and Effa Manley were fascinating individuals. To me, the players should always be the story, and I wanted to learn more about not just Paige and Gibson and Jackie Robinson, but Buck Leonard, Oscar Charleston, and others.

One white player who is prominently featured is Cap Anson, the 19th century great who staunchly opposed African-American players in professional baseball, leading to the so-called “gentleman’s agreement” among teams that kept blacks out of the majors. Kennesaw Mountain Landis is also criticized for failing to integrate baseball during his tenure as MLB commissioner, which ended with his death in 1944.

The NLBM takes about 90 minutes to tour (I was happy to see visitors of all races). The museum shares its building with the American Jazz Museum, and MLB’s Urban Youth Academy baseball/softball complex is part of the same block. The museum features great exhibits on African-American clown teams, which carried on into the 1950s, and on the sports writers and African-American newspapers that crusaded for integration in baseball.

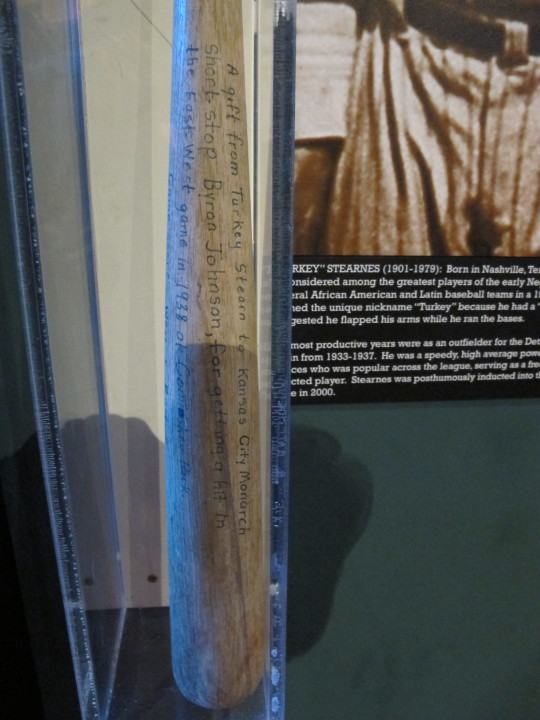

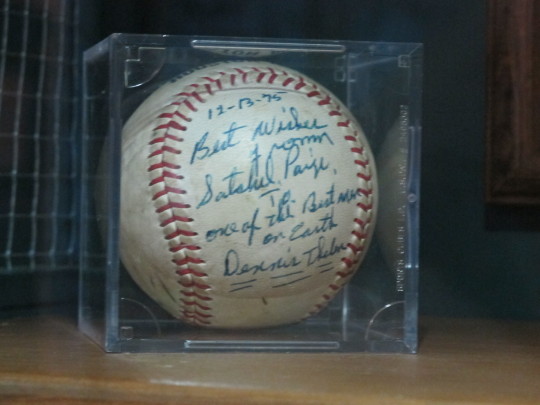

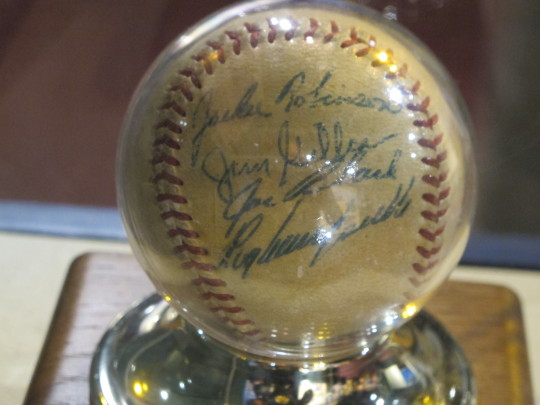

As far as memorabilia, the NLBM included signed Robinson and Paige baseballs, as well as my favorite piece—a bat used and signed by Hall of Famer Turkey Stearnes (nicknamed either because of the way he ran or because he had a pot-belly as a child). Stearnes played for the Detroit Stars, Kansas City Monarchs, and a host of other teams.

The museum also includes what it describes as lifestyle exhibits that highlight black businesses from the era, including a hotel room and a barbershop, though the exhibit emphasizes that most Negro League teams stayed in hotels far worse than the one depicted in the exhibit.

After Robinson and Larry Doby broke the color barrier in 1947, it still took 12 years before every major league team featured a black player. Although in decline after losing their star players to the majors, the Negro Leagues continued until 1960. The museum chronicles the demise of the Negro Leagues and the accomplishments of former Negro Leaguers in the majors (including Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Mays, and others).

The self-guided tour through the NLBM leads to a series of lockers featuring replica jerseys and the Cooperstown plaques of the Negro Leaguers who have been inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. There’s a set of pearls in Manley’s locker as well, fitting for the first woman inducted in the Hall.

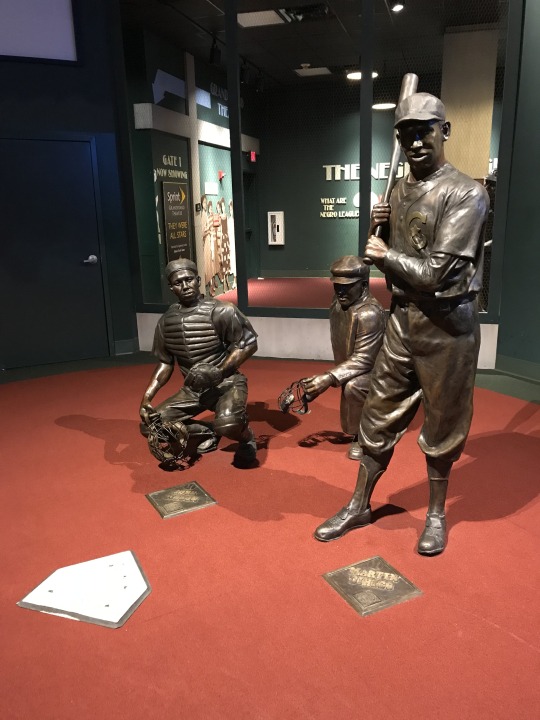

The tour concludes at the “Field of Legends,” which features a replica diamond with 10 bronze sculptures of Negro League greats in the midst of a game. Paige is on the mound, Gibson is behind the plate, and Martin Dihigo is at the plate. Leonard, Johnson, Bell, Charleston, Pop Lloyd, Ray Dandridge, and Leon Day are also on the field; Foster and Buck O’Neil have sculptures elsewhere in the NLBM.

My biggest thought in leaving the NLBM was gratitude that the museum exists. Our connection to the Negro Leagues fades by the day—O’Neil died in 2006, Aaron is 84 years old, Robinson broke the color barrier 71 years ago—but the history of the Negro Leagues is well chronicled in Kansas City.

0 notes

Text

That 70s Show

I don’t know why I didn’t attend the Mariners’ first turn-back-the-clock game against the Houston Astros on May 24, 2014. We had a 3-month-old baby at the time, which probably had much to do with it. The pitching matchup of Brandon Maurer vs. Brett Oberholtzer might have been another reason.

But as soon as I turned on the TV that night, I immediately regretted not going. The Astros and Mariners wore throwback uniforms from the 1979 season--with the original trident logo for the Mariners and the Astros in their iconic orange-red-yellow rainbow jerseys.

My regret only increased weeks later when Astros outfielder George Springer was pictured on the cover of Sports Illustrated on June 30, 2014, wearing the rainbow jersey from that night for a feature story predicting the Astros would win the 2017 World Series.

For me, the Astros’ rainbow jerseys are the greatest in baseball history. After missing the chance to see them in person at Safeco Field in 2014, I resolved never to let a similar opportunity pass again.

Three years later, the Mariners held another turn-back-the-clock game against the Astros. As part of their 40th anniversary celebration, the Mariners commemorated their inaugural 1977 season with their June 24, 2017, game.

That put the Mariners back in the trident uniforms and the Astros back in their rainbow jerseys, which they wore from 1975 to 1986. I had been given a second chance to see the Astros in their rainbows, and I wasn’t going to miss it.

As much as I love the Mariners, I might love the Astros’ rainbow jerseys even more. We bought tickets on the third-base side near the Houston dugout--the better to see those jerseys. For the first time, I dug out the rainbow throwback I have in the closet and wore it in public.

It was the first game I’ve ever gone to just because of the jerseys the teams were wearing. Watching the Astros spill out of their dugout every inning to take the field in their rainbows was simply wonderful.

It also was a rare sight: According to an excellent Houston Chronicle feature on the Astros’ unparalleled uniform history, the Astros have worn the rainbow jerseys only 10 times dating to 1999 (including the June 2017 game).

The Mariners’ entire turn-back-the-clock production was perfect--with the centerfield scoreboard done in dot matrix style, low def scoreboard replays, and 1970s music and movie quote games for between-innings entertainment.

Instead of the usual HD hydroplane race between innings, the Mariners offered a sailboat dot race that looked like something out of the Pong era of video games.

As for the game, the Astros took a 5-2 victory (improving to 51-25) as Brian McCann hit a three-run double to right field in the seventh inning. McCann’s sinking liner smacked off Mitch Haniger’s glove as Haniger attempted to make what would have been a spectacular diving catch.

* * *

A couple of weeks after the game, the Mariners auctioned the throwback jerseys for charity. There is apparently much love for the Astros rainbows--George Springer’s ($5,004), Carlos Correa’s ($4,000), and Jose Altuve’s ($3,700) jerseys all went for eye-popping sums. Even the jersey of No. 9 hitter Jake Marisnick sold for $510.

All I wanted was a game-used rainbow jersey of someone who played in the game. And I was fortunate enough to win Luke Gregerson’s No. 44 for $320. Gregerson faced three batters in the seventh inning as one of five relievers who preserved the win for Lance McCullers Jr.

I can’t wait to frame the jersey and hang it in our playroom. It will be a forever memory of a second chance to see the greatest uniforms in baseball history in person.

* * * Four days after the Astros wore their rainbows, ESPN.com’s Uni Watch correspondent Paul Lukas wrote a feature all about the jerseys. I think my favorite fact is that the Astros did not have separate home and road jerseys from 1975 to 1980--the rainbow jersey served as both.

* * *

Some of the action photos from the Seattle Times and Associated Press from the turn-back-the-clock game, showing the rainbows in all their glory.

0 notes

Text

Summer Catch

Walking up to the baseball field behind Dennis-Yarmouth Regional High School, you hardly would believe that Chris Sale, Buster Posey, Justin Turner, and a host of others called it their summer home on the way to the majors.

Red Wilson Field features a wooden press box, a chain-link outfield fence (with no marked dimensions), a snack bar, and some scattered bleachers. There’s not even stadium lights so games can be played after dark.

But such is the essence of the Cape Cod Baseball League, with the unmatched combination of small-town charm and big-time prospects. For two months every summer, the country’s top college baseball players head to Cape Cod to play for the league’s 10 teams.

The league stretches some 60 miles across Cape Cod and along Route 6, from Wareham (Gatemen) and Bourne (Braves) in the west to Chatham (Anglers) and Orleans (Firebirds) in the east. The teams are split into East and West Divisions and play 44-game schedules.

For this year’s baseball trip, I headed to the Cape League for a June 17 game between the Harwich Mariners and Yarmouth-Dennis Red Sox. It was the home opener for the three-time defending league champion Red Sox; admission was free (with donations gladly accepted). The drive from Boston to the town of South Yarmouth took about 75 minutes.

The Cape League’s history of producing future major leaguers is staggering. According to the league, 297 former Cape League players appeared in at least one major-league game in 2016—that would be the equivalent of almost 12 full 25-man rosters. The league has more than 1,100 former big-league alumni.

Among current Mariners, Dan Altavilla (Y-D), Taylor Motter (Harwich), Kyle Seager (Chatham), Danny Valencia (Orleans), Mike Zunino (Y-D), and Tony Zych (Bourne) all played in the Cape League.

This year, 10 of the 36 first-round MLB draft picks were Cape League alums, including top-10 picks Brendan McKay (Tampa Bay), Pavin Smith (Arizona), and Adam Haseley (Philadelphia).

Not surprisingly, the Cape League is heavily scouted. We counted four or five scouts sitting behind home plate at the Y-D park armed with radar guns, with several scouts packing up and leaving at 6 p.m. to presumably catch a second game on the Cape that night.

My interest in the Cape League grew from Jim Collins’ fantastic book “The Last Best League,” which followed the Chatham A’s (now Anglers) for one summer in 2002. Tim Stouffer and Chris Iannetta both became big-league regulars from that Chatham team.

But the book also focuses as much on the players who got so close to the big-time, yet failed to make it for one reason or another. (Collins updated the book 10 years later after the A’s players all had either established or finished their baseball careers.)

We originally planned to see a game in Chatham, but those plans changed after a rainout. Y-D was a great second choice—a 5 p.m. game that ended three hours later with the fog from the ocean rolling in across the field.

The Cape League is small-time enough that the homeowners beyond the right-field fence pulled up yard chairs and enjoyed dinner with the game. One man walked his dog through the Harwich bullpen mid-game (he later talked about watching Posey and Kyle Schwarber both play on the Cape, and claimed Cotuit has the best park).

One of the Y-D players was in charge of selling tickets for the 50/50 raffle (Cape League teams must raise $200,000 annually). And at the neighboring football stadium, the high school was holding a walk-a-thon dedicated to cancer support, with music blasting the entire evening.

The Red Sox and the other Cape League teams each employ squadrons of interns, who handle everything from marketing to running the concession stand. The teams additionally air their games online using broadcasting students.

Some of the players still work part-time during the summer, while playing baseball in the afternoons and evenings, although this has become less common as players focus on getting scouted. First-round bonus values now range from $7.8 million to $2.2 million.

I assume that I saw at least one future major leaguer--the Cape League’s slogan is “Where the stars of tomorrow shine tonight!”--but I’m not sure who that would be. We went on the season’s first weekend, when several players whose college teams made deep NCAA Tournament runs had yet to arrive (according to the league, 62 players this season went to NCAA super regionals and 39 went to the College World Series).

Harwich third baseman Ryne Ogren had the game’s biggest hit, belting a two-run double to cap a four-run fifth inning for the Mariners. I thought Harwich outfielder Dwanya Williams-Sutton and pitcher Matthew Frisbee also seemed like potential prospects, along with Y-D outfielder Carlos Cortes, who had three hits.

The Mariners also got 4 2/3 scoreless innings in relief from Austin Hansen, Brian Christian, and Theodore Rodliff. The teams combined for 22 hits, but the players were still in their first week and seemingly adjusting to the wood bats of the Cape League after the metal bats of college.

(According to Collins’ book, MLB allows Y-D and Harwich to use the Red Sox and Mariners names, provided they order merchandise through MLB’s licensees. The Red Sox cap actually uses the White Sox logo against an outline of Cape Cod; the Mariners use a compass logo just like Seattle).

The featured event for the season is the annual All-Star Game (held this year on July 22) and the championship series in mid-August. There’s a game of the week broadcast on Fox College Sports as well. Or you can just wait a couple of years to catch the league’s biggest stars in the majors.

I’m looking forward to checking this post in about five years to see which of the players below ended up making it. We saw all of them play in the Mariners’ victory.

From Harwich: Joey Bart C (Georgia Tech); Brian Christian (P) (Northeastern); Nick Dalesandro (RF) (Purdue); Brad Debo (DH) (N.C. State); Matthew Frisbee (P) (UNC Greensboro); Austin Hansen (P) (Oklahoma); Owen Miller (SS) (Illinois State); Kyler Murray (PR) (Oklahoma); Ryne Ogren (3B) (Elon); Teddy Rodliff (P) (Stony Brook); Cameron Simmons (CF) (Virginia); Cobie Vance (2B) (Alabama); Jordan Verdon (1B) (San Diego State); Dwanya Williams-Sutton (LF) (East Carolina).

From Yamouth-Dennis: Cameron Beauchamp (P) (Indiana); Karl Blum (P) (Rutgers); Michael Cassala C (Jacksonville); Charlie Concannon (DH) (St. Joseph’s); Carlos Cortes (LF) (South Carolina); Kole Cottam C (Kentucky); Jake Crawford (1B) (Furman); Jonah Davis (RF) (California); Tyler Depreta-Johnson (SS) (Houston Baptist); Tanner Graham (P) (Alabama-Birmingham); Nico Hoerner (2B) (Stanford); Kyle Isbel (CF) (UNLV); Christian Koss (3B) (UC Irvine); Hunter Parsons (P) (Maryland); Carter Pharis (1B) (Alabama-Birmingham); John Rooney (P) (Hofstra); Christopher Sharpe (CF) (UMass Lowell).

0 notes

Text

Home of the Braves

If you were to list the major league teams in need of new stadiums a couple of years ago, the usual suspects of the Oakland Athletics and Tampa Bay Rays might have been the only two teams to make the list. Such is the product of the stadium-building boom across baseball in recent decades—nearly every team seemingly had a place to call home for a generation.

Or so it seemed for the Atlanta Braves. Only 20 years after moving into Turner Field—built for the 1996 Olympics and converted for baseball the following spring—the Braves abandoned downtown Atlanta for their new home at SunTrust Park in the Cobb County suburbs north of the city.

More than just leaving the Atlanta city center, SunTrust Park represents a new era in stadium building. The Braves have developed an entire entertainment and commercial district around the stadium, with the potential of generating revenue year-round from sources beyond the 81 games a year scheduled at their ballpark.

The Braves christened their 41,149-seat, $622 million stadium this year, but they also are partners in the neighboring 10-story office building, a 500-room Omni hotel, and a music venue in the development known as The Battery. There are restaurants and bars already operating on site (including a Yard House) and plans to open additional outlets, including something touted as the Garden & Gun Experience (after the noted Southern magazine).

The best comparison for SunTrust Park might be the Ballpark at Arlington, which is also located in a suburb off the highway between Dallas and Fort Worth. SunTrust is located near the intersection of Interstates 75 and 285. The best comparison for the entertainment and commercial project might be the L.A. Live development located next to Staples Center.

I took advantage of an East Coast trip to swing through Atlanta and catch the Braves’ June 18 Father’s Day game against the Miami Marlins. SunTrust Park is the first new MLB stadium to open since Marlins Park in 2012. The trip got me back up to having visited all 30 current parks in the majors.

The Braves won 5-4 as Brandon Phillips drove in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth inning after Marcell Ozuna had tied the score late with a two-run homer for the Marlins. But with both teams well under .500, the game was really secondary to the new ballpark experience.

There were things I liked and didn’t like about SunTrust. It felt in many ways like a temple to everything involved in going to a major-league baseball game, but not actually watching the game (shopping, eating, private clubs, kids’ activities). And doesn’t that miss the entire point of going to a baseball game?

But these features are probably necessary for any new stadium being built these days, though it did make me appreciate the relative simplicity of my home park at Safeco Field.

As far as what I liked and didn’t like about the majors’ newest park:

Parking: The parking situation at SunTrust is horrific. It looks completely improvised, with the Braves creating lots out of parking lots of nearby hotels and office parks. I would never pre-purchase a parking permit for a game—there’s typically a much better deal to be found—but SunTrust would be the exception to that rule.

Having driven by a half-dozen permit-only lots, I was directed to a cash lot in an office park on the other side of Interstate 75 where I couldn’t even see the stadium from the lot. If you told me I was in a different zip code or area code from the ballpark, I would absolutely have believed you.

The walk to the park took 15 to 20 minutes, through a Marriott parking lot (permit-only for Braves games), and across the highway. The Braves charged $20 to park in this lot, despite being a mile at least from the stadium, and it was completely full when I came back to my car.

Walking into the stadium, I thought that I would go to like two games a year if I lived in Atlanta given the headache of just parking at SunTrust. (And that’s on a Sunday when there wasn’t even traffic to deal with in getting to the park.) Fortunately, there’s enough to like about the park that the parking situation did not completely overshadow the experience.

It’s worth noting the Braves have partnered with Uber and Waze to try to overcome some of the traffic and parking headaches for their fans. There was a massive line of Uber drivers waiting to pick up fans after the game. But it just seemed to me like the Braves found a site for the stadium and development, and the parking plans are going to have to come in future seasons.

Entrance to SunTrust: There is not a traditional home-plate entrance to the stadium. The first entrance in walking up from parking on the other side of I-75 is the third-base entrance. There are statutes of Phil Niekro, Bobby Cox, and Warren Spahn circling the stadium perimeter, which I thought was a nice touch. Niekro is throwing a knuckleball in his statute.

The Braves have created an outstanding fan plaza beyond centerfield. There was a drum line going an hour before the game, and the Braves brought back four players to sign autographs for fans in the plaza (leading to the question of who thought John Rocker was an appropriate choice to welcome back).

Brewery: I give the Braves enormous credit for including a brewery on site at SunTrust. That will undoubtedly be a feature copied by numerous other teams. Terrapin Brewing Co. brews select beers on site at the park, including a version of its Hopsecutioner IPA (called the Chopsecutioner IPA) that is brewed using wooden bats.

The Terrapin tap room (adjacent to the centerfield plaza) serves Fox Brothers barbecue. The tap room was busy enough that fans were being told there was a two-hour wait for food before the game. I was able to step up and grab a $6 Chopsecutioner without any wait, which seemed like a bargain based on stadium beer prices.

Monument Park: The Braves built an expansive monument park on the main concourse behind home plate. The park pays tribute to the combined history of the Boston/Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves, with the Braves noting that they are the longest continuously operated major league team. There’s even an explanation of how the Braves got their name.

A statute of Hank Aaron connecting for his record-breaking 715th homer is the centerpiece of the monument park. The Braves also display their 1995 World Series championship trophy, Aaron’s MVP award, and Greg Maddux’s Cy Young award, in addition to other trophies and memorabilia.

Price and Sightlines: I was almost dumbfounded to get a $9 ticket in the 300 level (not even the upper-most 400 level) with a great view along the right-field line. I spent four times that to sit in basically the same spot for the Blue Jays/Mariners game a week earlier. The sightlines all over SunTrust seemed great—I even liked the view from the outfield bleachers looking back on the field.

The Sandlot: The Braves built a kids’ zone called the Sandlot that was supremely impressive. The featured attraction appeared to be a full zipline, but there was also a climbing wall, a race track, and a host of other games. The only downside seems to be that the Sandlot is so compelling, the kids and their parents might have little reason to watch the game at all.

Organist: I appreciated the cleverness of the Braves’ organist, which is definitely not the trend at baseball parks these days (the Dodgers reduced their longtime organist’s role a couple of seasons back). The SunTrust organist played the theme from Batman when the Marlins’ J.T. Riddle came up, “Coming to America” for A.J. Ellis, and the theme from the Wizard of Oz in honor of Ozuna.

Tomahawk Chop: Can we please retire the tomahawk chop, which shows less than zero cultural sensitivity? It was almost unnerving to watch Brian Jordan lead the crowd in the chop during the first inning.

Extended Netting: The Braves are the first team I’ve seen that has extended the foul netting from behind home plate to over the home and visiting dugouts. There’s no good reason not to do this and save a family from having to go to the emergency room because their kid or mom got drilled by a liner. I saw at least two liners that the extended netting kept from screaming into the stands.

Attendance: I was shocked that the Braves drew only 36,912 for the game (5,000 below capacity). What team doesn’t sell out on Father’s Day? Part of the Braves’ explanation for moving out of downtown Atlanta was to be closer to their suburban fan base. But there was no shortage of empty seats, with tickets that obviously went unsold and also fans who seemingly were caught up in the park’s other diversions.

Even though it wasn’t a sellout, I thought the Braves also struggled to handle the crowd. Every team store had a long line of fans waiting to get in. I didn’t end up trying any food at SunTrust (other than the Chopsecutioner) because it looked like a multi-inning investment to wait in the concession lines.

(From what I saw, the food options looked very strong, with everything from barbecue stands and gourmet burger stands to hot dogs and popcorn to Chick-fil-a and Waffle House to a chophouse and the fancy private clubs. Bonus points for having outposts of everything in the upper deck, which is not the case at many stadiums.)

Design: I thought the brickwork at SunTrust gave it a really distinctive look. For being next to the interstate, it’s visually appealing from the outside. And the brick along the infield and outfield walls just works. The hotel and office building (which is a regional headquarters for Comcast) create a recognizable outfield backdrop for what otherwise would be woods, highways, and office parks.

The Freeze: I couldn’t help but leave a little disappointed because the Braves did not stage their racing promotion where The Freeze, an Olympic-caliber sprinter who works on Atlanta’s grounds crew, chases down a hapless fan given a head start in a race around the warning track. The Braves don’t run the promotion every game; we got a tool race sponsored by Home Depot instead.

* * *

All things considered, I would rank SunTrust Park as comparable to Target Field and Marlins Park. I didn’t like it as much as the new-era parks in San Francisco, San Diego, Seattle, and Colorado. And it just can’t add up to the experience of seeing a Yankees game in New York at the new Yankee Stadium. I would rank SunTrust ahead of Citi Field and Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia for sure. I could see, though, the parking and traffic situation being so problematic that some nights the stadium just would not seem functional at all.

It’s a park in the top half of major league stadiums, which is a solid accomplishment given that there have been so many quality ballparks built in recent years. It’s also better than what I originally expected when I heard the Braves were building a ballpark 10 miles outside of downtown in the suburbs of a neighboring county.

I expect the Braves will put down roots at SunTrust longer than the 20 years they stayed at Turner Field (which is going to be converted into a football stadium for Georgia State University). To get from the airport to SunTrust, in fact, you have to drive past the relic of Turner Field downtown. I had no issue with Turner Field—I ranked it higher than many—but SunTrust is a definite upgrade.

For what it’s worth, it looks like the next new stadium will belong to the Texas Rangers and open in 2020 or 2021. I keep holding out hope for a new park in Oakland and (for once) an easy trip to see a new ballpark.

0 notes

Text

See the Future

Back in the fall of 2011, baseball fans could have watched Mike Trout and Bryce Harper regularly play in the same outfield as Scottsdale Scorpions teammates during the Arizona Fall League’s annual six-week season.

That fall marked the pinnacle in AFL history, even if it was little noticed at the time. Now in its 24th season, the AFL serves as Major League Baseball’s self-described “graduate school,” where top prospects don major-league uniforms and play in big-league spring training parks as one of the last stops for many on their way to the show.

Following from afar, I’ve long believed the AFL—with its “See the Future” slogan for 2015—might be the most underrated event in baseball. The weather is the same as spring training (only in October and November), but the crowds are non-existent by comparison. Every year, the AFL features a who’s who list of prospects, though not always a Trout-Harper combination.