fandom and weird shit || biology blog: ryno-latrans || cryptid blog: ryno-qq || pfp: owlyjules

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

De-aged Jason Todd and his morally-grey parental figures + Dick

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

De-aged Jason Todd and his morally-grey parental figures + Dick

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Do you want to make a stop for Batburger?”

[Incoherent concussed Jason noises]

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Batfamily reunion, kinda ?

Not my idea: https://x.com/tocartss/status/1897135638438404416?s=46&t=zkCvxQnVoZvDMu4v7483qg

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

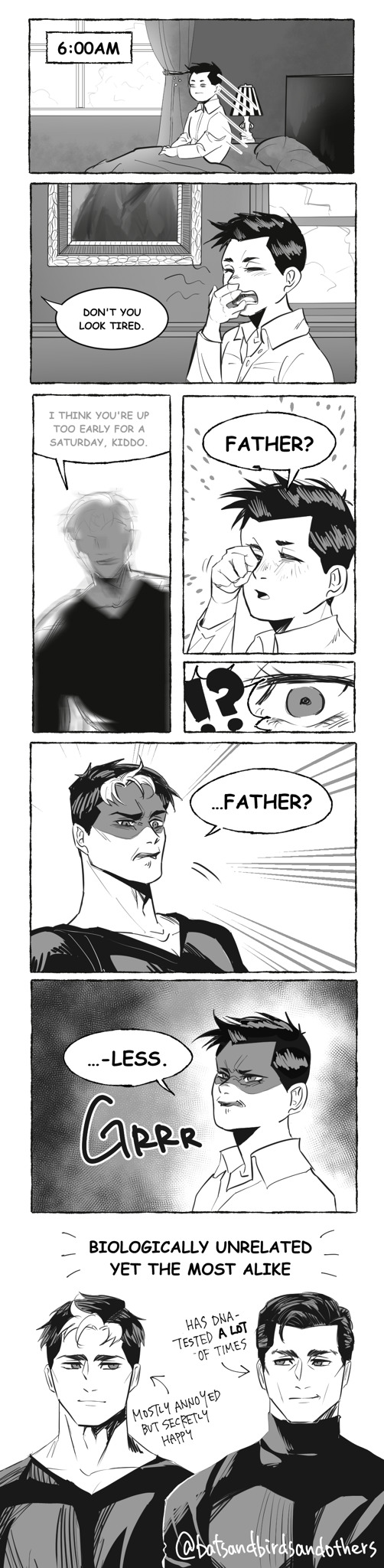

Poor Dick :(

Commission Info / Kofi (members get comics a week early)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Batbros reference for myself that I probably will only use twice🩷

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok last of the pinescone for tn hehe

pjs books and cuddles

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Queer Ecology Taught Me About Survival, Belonging, and Love. 🌈🌎

Did it ever occur to you that the animals, plants, and fungi might be queer? If not, that is exhibit A in our case for the importance of Queer Ecology, a field that challenges our heteronormative, cisnormative, and anthropocentric views of the natural world. It recognizes the fluidity and diversity of identities and relationships in both human and non-human realms. It aims to foster inclusive relationships with the environment and life that encompass and celebrate its broad spectrum, rather than limit it. It collapses systems of oppression and blooms a new regenerative perspective.

A Queer Ecological History

Understanding Queer ecology can be confusing for many of those who do not interact with academic institutions. The praxis of queer ecology is understood through how we perceive the binary concepts of natural and unnatural. Who is natural, and why are Queer bodies seen as unnatural? Who deems us unnatural, and why?

I was born in Los Angeles, California, and as a young Mexican-American, my identity or sexuality was not allowed to express deviance from the norm. It was simple, I was born a boy, meant to fall in love with a girl. Any other thoughts, expressions, or embodiments of feminine acts were seen as an error in my genetic code. My early life was marked by disappointment from my parents and their attempts to mold me multiple times.

Due to my rebellious nature as a youth, I uprooted and challenged harmful narratives that were attempted to be inflicted on me. I love my parents today, we’ve done a lot of healing, and I am privileged to have a healthy relationship with them now.

As a teenager, I worked weekends from 8 AM to 6 PM in the gardens of affluent people in the Los Angeles region with my father. I usually wore a long, red flannel shirt, huge dark denim jeans, leather-welted boots, and a straw hat to protect my body from the intense solar rays. I was always forced to remove the weeds that I saw as revolting against uniformity and presenting true diversity.

Dandelions are sacred yet seen as hindrances. Any mushroom was seen as deadly, poisonous, and a representation of toxicity, but I saw it as a system that recycles and removes toxicity from life. The fauna were seen as pests, and I was forced to spray harmful chemicals to remove them when they only tried to find their way back home.

My dad and older brother did more of the heavier work by climbing trees, and sometimes I joined them, almost falling myself, but thanks to my extended height, I was able to catch myself.

These species were like me, trying to find their home in what they thought was a shared space. Slowly, I began to understand that my passion for environmentalism stemmed from a place of brutal isolation, a place where I could explore the pain that resided in the corridors of my heart.

As the years went by, I slowly became a small shell of myself, too sick to breathe the seas of sleep and believing that I belonged nowhere because I was Queer. I found the eeriness of the lost forests and outdoor spaces to be a place to grieve. A place for pain so deep that I knew only the species that didn’t speak my language knew how to guide me back to my ancestors. I was feeling soulless and slowly started to climb from what seemed like endless vines against a cliff, a pathway that held my head high as I searched for the glistening light.

Bi-sexual! No, gay! Wait, Queer is who I am. I hated conforming to societal boxes. It was almost as if people needed to know one answer when multiple answers existed in my head. I had fallen in love with a woman before, a man, and someone who was non-binary. All of these experiences taught me about different portals into worlds I could live in, yet they allowed me to connect with the broader struggles of all gender-diverse groups.

One of the reasons I love being queer is because it’s an expansive identity and way of seeing the world. When I talk to some gay men, they don’t always understand that my attraction to gender-diverse people often shows up through conversations, art, literature, and culture. That is also a form of intimacy rather than the idea we have of having to be in physical contact (i.e, kissing, holding hands, etc).

It’s not that I won’t end up with a man (because I already know I will, lol), but my view of love is rooted in abundance, not limitation. And queerness also varies per individual, my view may be different than my peers and that’s okay too. But being able to come into my queerness when I was 22 allowed me to finally come back home to who I truly was.

I had formed a community, fallen in love, and fallen out of love, and I remembered that the moment I started to live for others was when I was disarming myself. Life became bright, joyous, and queer when I stepped into power.

Why is queer ecology important?

The world we live in is queer. This isn’t a personal opinion; it is a scientific fact. Scientists have observed non-binary, homosexual, transgender, and intersex relationships and identities occurring as naturally in ecosystems as their hetero/cisnormative counterparts. Or rather, ecological relationships (ecosystems) don’t exist within binaries, but instead occupy a full spectrum of existence.

Queer ecology offers us a critical lens through which to understand these relationships, beyond the narrative of the binary. When we’re limited or fixed in what we know as natural versus unnatural, or appropriate versus deviant, we misinterpret the world around us.

Hetero/cisnormative perspectives assert views like sex being based primarily on biological reproduction and these values go on to shape human interactions with their environment, other humans, and non-human animals. What might happen if we prescribe values outside of cis and heteronormative norms? Queering nature is our connection to an expansive view that examines the wide possibilities of relationships, not their limits.

What it Means to be a Queer Environmentalist

I’ve always struggled with what it means to be a Queer environmentalist. Sometimes I say nothing. Being a queer environmentalist implies that I value multi-species liberation and recognize that we live in a world of curiosity and connection, where there is no single answer to how we should live.

It means that I wish to see white supremacist systems be collapsed and to recognize the queer ecological histories and eulogies of the Queer / Trans BIPOC leaders who have come before me and honor them in my work. Especially in a time where transphobia is at a rise and our Trans siblings have the highest rates of deaths yet they are the ones who have always and continue to be at the forefront of Trans / Queer liberation.

But the reality is that my love for environmentalism exists on an expansionary scale rather than a fixed value. Throughout my life, my passion has taken different forms of expression, whether through movement, literature, music, or writing. I’ve had several mystery-based experiences with people throughout the world, where we never seem to be able to describe our care for each other, but instead envelop ourselves through embodiments of care.

Perhaps that is how we have forgotten the lost stories of species around us, primarily the non-human, in how they interact, not just to stay alive but also to enjoy themselves in a world that is constantly changing.

Queer ecology belongs in our movements

In the United States, there has been a record increase in anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes, movements, and legislation that seek to block or challenge the existence of these individuals. This may as well be Exhibit B. The idea that humans and nature are separate, and the dominance of this idea in our culture, is made apparent within these perspectives. We know from the environmental justice movement, and the BIPOC communities where it originated, that our environments and our bodies are inseparable. The environment in which a person lives is the most significant determinant of their health.

Queer ecology has a practical role in social justice movements, especially as queer populations are often at-risk, and face social and environmental violence, and health and economic disparity. Without this inclusive perspective, there is a perpetuation of violence, exclusion, displacement, and exploitation. A glance at the vast history of life on Earth reveals that diversity is the foundation of life. If we examine nature through a queer lens, we can approach our issues more holistically. We gain an understanding of kinship and connection that crosses boundaries.

For a long time, nature has been treated as separate from humans. This perspective became a foundation for modern environmentalism, seeking to “protect” nature from humans. This same perspective has been romanticized in popular and past environmental literature and it helped enable the erasure and removal of Indigenous peoples. Culture and nature were treated and viewed as separate, and Indigenous peoples were removed by colonizers, upholding this worldview.

This is relevant to queer ecology as it seeks to critically analyze and go beyond our binary perspectives, which are often associated with hetero/cisnormative values. When we explore the world of possibilities available to us beyond these binaries, we become more inclined to challenge the logic behind displacement and environmental violence, create inclusive systems, and form bridges between different ways of seeing and being. Queer ecology can lead to openmindedness.

This has practical implications, as cis/heteronormative views have shaped our public institutions, environmental policies, and our relationship to nature. Environmental scholars like Catriona Sandilands have pointed out that Indigenous removal from wilderness preserves serves as one example, but we can also examine how institutions like the public park and other urban green spaces present gendered and racialized biases. Urban parks are designed to create specific types of nature experiences. The easiest way to illustrate this is to examine what is allowed and what is not allowed in these spaces.

For example, having a green space for playgrounds, sports, dog walks, and birthdays addresses some of the common uses found in urban parks today. However, a queer community might place more value on a closed sexual space, a safe place for expression of desire and gathering. The answer isn’t necessarily to have sex in parks. But instead what do queer healthy spaces look like too?

Still, this understanding reveals that the design of parks as a public institution is rooted in heterosexual communities and their health. This cisnormative view of health begs the question: how might queer communities have different possible uses? These are precisely the types of questions and perspectives that queer ecology invites us to explore, and the norms to challenge on a journey to an understanding of humanity that is as diverse and inclusive as life on earth.

In an academic sense…

The origins of queer ecology were first examined through queer theory in Michel Foucault’s work, The History of Sexuality, published in 1976. Environmental scholar and writer, Catriona Sandilands, went on to conceptualize queer ecology and cites Michel Foucault as laying the groundwork for the connections she drew later on. Her book, Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, gained recognition for providing a comprehensive analysis of the intersections between sexuality and environmentalism. In 1990, Judith Butler explored the concept of gender as performance in her book, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Translating this idea into a queer ecological framework suggests that humans that categorize “nature” and “culture” as separate are performing those differences. From a scientific perspective, nature more accurately exists in a flow and system of interactions, rather than any determined and fixed states. Queer ecology also has close ties to ecological feminist theory.

The ideas behind queer ecology have evolved into new narratives that celebrate diversity and promote rights for the LGBTQ+ community. From “Climate of Gender” by Callum Angus:

“Trees and people live in transition now, perhaps permanently, and I do not think this is all bad. Such a shift in climatic thinking requires accepting loss sometimes, and remembering where we’ve been, what we’ve done wrong, and a willingness to find new things beautiful. It requires recognizing the beauty in new definitions of gender, allowing the expansiveness and creativity of trans people to revise what we thought was known about gender in the past. It requires adaptation to new seasonal rhythms, yes, but adaptation with an awareness that this is not the first time whole societies have been forced to adapt to change they didn’t want, and a willingness to listen to those communities with much more respect than we have in the past.”

As a trans male, Angus draws connections between his experience transitioning and the transitions happening as a result of the climate crisis, suggesting that it presents an opportunity for reckoning. Queer ecology helps us gain a deeper understanding that the environment and marginalized communities face parallel struggles for their right to exist, while informing us on how to create a more inclusive and sustainable world.

Organizations that center queer identities and ecology, such as Queer Nature, demonstrate how queer ecology can manifest as a practice, in addition to a framework or lifestyle. Their work envisions and implements ecological awareness and outdoor self-efficacy skills, including bushcraft, plant identification, and tactical skills. In our daily lives and environmental practices, queer ecology encourages us to question our assumptions and embrace diversity in all aspects of our lives, fostering a world where we all belong. It invites us to reflect on our environmental identities (an interconnected concept of self), challenge our consumptive or extractive behaviors, and promote inclusivity in our art, spaces, systems, institutions, and policies.

Queer ecology is an ever-expansive field and there is always new analysis and dialogue to be held. In my view of work for queer ecology, I am not an expert in this field, but rather someone who wants to share my story about queerness. One that was rooted in resilience after turmoil, trying to find abundance, is the cornerstone around the world that enables me to continue doing the work I do today. I still see that our LGBTQ+ communities are suffering worldwide. I fear that we are entering a world where there will be more hate than love, and that in our interpersonal relationships, we struggle to build intimacy.

However, amidst the despair I see around the world, there is always beauty blossoming in the bleak landscape. I see myself as someone who was born bleak, yet beautiful. There are many aspects of myself that I have begun to love again, which I thought had wilted when I was young. This is the beauty of aging in an evolving field: you get to rediscover the world from a more compassionate perspective. And that’s why queer ecology keeps me alive not because of seeing gay penguins but because somewhere in my lineage there was also someone who was Queer that carried the desire to care, love, and nurtue for others despite going through hardship.

Solving the climate crisis requires us to develop a deeper understanding of the world around us and the complexity of relationships that have enabled life to thrive. Queer ecology represents a pathway to this understanding. If we don’t recognize and celebrate the diversity in the world around us, we risk losing it all. As younger generations rally around intersectionality, there’s a chance to lay a foundation for new stories. Angus ends “Climate of Gender” with these final lines:

Perhaps future civilizations will tell stories in which wildly oscillating weather patterns at the turn of the twenty-first century were the result of great planetwide suffering. Or they might inherit a legend that tells how great change sparked great cooperation in nourishing the land and each other because, as is often the case with transition, the possibility for new stories opened up.

By Isaias Hernandez, @queerbrownvegan

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Medieval peasants couldn’t handle my Spotify playlist” but could YOU handle a medieval bard relaying the epic of Beowulf over the course of an hour? Humble yourself.

65K notes

·

View notes