A photographic journey into the survival of the Eelam Tamils, the preservation of their identity across the globe, and the role of women in this story.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

TW: sexual violence.

In 2009, we watched from afar as our people were slaughtered in our homeland for 6 months.

We carry with us the stories of the extra judicial killings, the torture, the dissapearences and the rape camps that were set up by the Sri Lankan Govt. We hold within us deep grief knowing our elders in Eelam are dying, before knowing what happened to their missing children and while some are still in prison.

There is so much horror in so many countries and state violence against refugees continues to get worse and worse. The cruelty we have come to normalise is terrifying.

For the last 6 months we have watched the genocide of the Palestinian people play out in real time on our social media accounts.

Living again through the photos of white phosphorus attacks, the emaciated bodies, the hospital bombings and the dead children is so painful.

But if you are fortunate enough to live in a place in which you can attend protests, you have a social media platform, you can raise your voice without fear of being killed or imprisoned, you can participate in boycotts and strikes and you can create art - it is an honour and a privilege as a Tamil to stand in solidarity with the people of Palestine in their struggle for freedom and liberation.

The news of sexual violence that is coming out of Al Shifa Hospital (Gaza) today is so heart wrenching. I am crying in rage about Isaipriya acca all over again. The stories of sexual violence I have heard from Tamil survivors are playing on repeat in my head. The betrayal of international leaders to let 2009 and 2024 happen will never be forgiven.

The scars of the Tamil genocide run deep. They no longer control me. But they do define me.

In this moment I am both a daughter of Tamil Eelam and a Palestinian.

Being silent as history is repeated is not an option.

🍉🇵🇸✊🏾

- BJ

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DARSHINI Melbourne, Australia

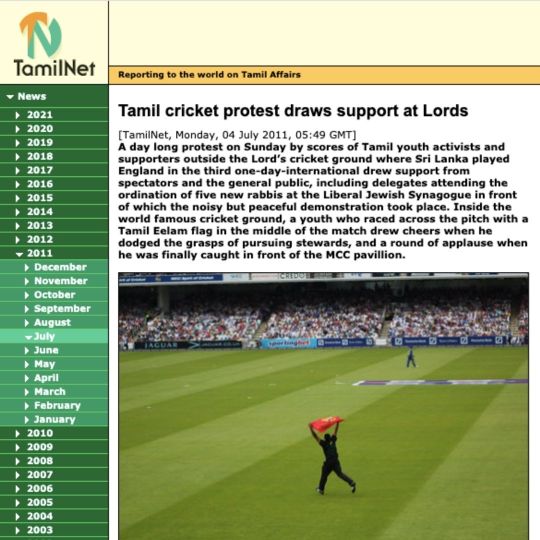

~ THE SARI STORY ~ July 1979, London ~ My Amma, a smart and beautiful nursing student from Malaysia, had just met my Appa, a skinny engineering student from Sri Lanka. They met properly at a cinema. Appa being incredibly punctual arrived early with his mate at the showing of இளமை ஊஞ்சலாடுகிறது (Ilamai Oonjal Aadukirathu) staring Kamal Haasan and Sripriya. Amma and her friend had decided last minute to see the same movie and arrived fashionably late. By chance, the usher seated my Amma next my Appa. It wasn’t until intermission when the lights came on that they set eyes on each other and, well, the rest is history… After meeting at the movie, my parents went on a couple of dates around London together. On the second date, Appa asked if Amma would accompany him sari shopping to help select a sari for his sister back in Sri Lanka. Of course, Appa was completely in love with Amma and was really buying the sari for her but he knew that she wouldn’t have let him spend money he didn’t have if he revealed what he was really up to! In the end the sari deception only lasted 2 days. Appa summoned the courage to present her with the sari and declare his love for her. It seems that Amma was equally smitten as they both excitedly agreed a plan to marry. On 24 September 1980 they were legally married/registered in London without their families present (so rebel!). They subsequently returned to Malaysia for a full traditional hindu wedding ceremony with both sets of parents in attendance on 20 August 1982. These pictures of Amma in the sari were posted home to Sri Lanka and Malaysia with news of the impending marriage and so it was through these pictures that my paternal grandparents first laid eyes on their daughter-in-law. Sarees are timeless. So much history, so many stories, are held in the threads of the 6 metres of woven fabric as they are passed from each generation of women to the next. It was so special to be able to wear my Amma’s sari, a piece of my parents’ love story, 42 and a half years in the making. 💕

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

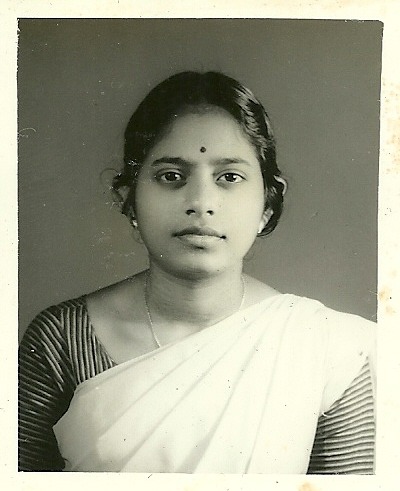

Photo 1: Violet Jesudas, Wellawatta, Illangai Photo 2: Anna with her amma Sugi and appa Harry, 1985, Geelong, Australia The below is an article that was published on Warscapes by Anna Arabindan Kesson in 2019. Remembering the Sri Lankan Civil War My grandmother always reminds me: you have lost your mother-tongue. When I return to Sri Lanka for brief visits, she tells me how I used to understand her. Like my nephews and nieces do now when I was a child, I would listen to spoken Tamil and reply in English. There is nothing I can say to her accusation except to agree. Yes, I have lost my mother tongue, the words, the sounds, the rhythms of speaking to which I was born. I willfully lost this language, after we moved to Australia where my voice, my skin, my body continually marked me as foreign, different, other. As we all know, primary school children can be cruel: losing my mother-tongue was a way to survive. I have often wondered if, had I continued to learn and speak Tamil with my mother, I would find myself now, almost thirty-five years after our migration and ten years after the end of the Sri Lankan civil war, with more articulate means of commemorating the past. So much has been lost as a result of that war. Tens of thousands of Tamil lives were lost – a genocide occurred and still remains unacknowledged – the destruction of Tamil sacred sites and their reconstruction into Buddhist temples, the seizure of formerly Tamil-owned land in the north by the government, the erosion of villages and communities through displacement and the disappearance of family members whose whereabouts remain, even ten years after the war’s end, unknown. While the government has created official memorials to commemorate their victory over the LTTE – a decimation that included the shelling of Tamil civilians caught in so called no-fire zones – no other casualties may be mourned. Former LTTE burial sites have been erased in the north and military monuments mark the site of major battles. In effect what continues to be lost is the experience of Tamils affected by the war. That is why I wonder whether, if I had recourse to the sounds and figures of Tamil, to the expressions and phrases and cadences of speaking and reading Tamil, I might also find another route to grieve and remember and commemorate that would allow me to move around the contested terrain of the war’s aftermath. In this contested terrain, so I am realizing, the history I have just described is disbelieved by some. In order to even remember what has been lost, I have to make a case for it. And to make the case I have to retell this story – a story that is part of me, although I did not experience its effects firsthand, although my family did, because I left Sri Lanka when I was almost six. So, my grief came from watching at a distance, it was formed from a place of safety for people I did not personally know. But retelling what I grieve for requires finding a language within a language, it means framing within recognizable forms, describing using recognizable signs, summarizing using familiar terms. Because, commemorating these acts of genocide when they take place in non-western countries also requires producing their reality for the west. But language has also been politicized in Sri Lanka; In 1956, under the Official Language Act No. 33 Sinhala was declared the only official language, replacing English which had been imposed under British colonial rule. It was only in 1988 that Tamil was legislated as an official administrative language of the country (not just the north-east region as was legislated by the 1958 Tamil (Special Provisions) Language Act). Language in Sri Lanka is so inextricably linked to identity, has been so carefully legislated to divide communities and generations and is now identified as a key component of the post-conflicted reconciliation process. Because of this importance, where and how we recount these narratives becomes all the more urgent. As V V Ganeshanthanan writes, to mourn these deaths requires a series of retelling: I must retell not only the version of the story I consider the truest and the worst, but also the versions in which no one died, or in which those who died are unworthy of mourning. My words must reenact and contain not only the deaths and my grief, but also their negation. One must parse and explain what is lost. Yes, lives. Also, land. And homes. And then there is the matter of those who have not been returned, who remain in camps awaiting resettlement, somewhere between lost and found. Always we remember those who have been taken away and remain unknown – neither lost nor found, neither alive nor dead. Lost too is trust, or at least a belief that politicians might work towards some kind of reconciliation and return of Tamil civil rights. When the war ended, then President Rajapaksa announced this ‘liberation’ from terrorism was the beginning of a new phase of unification. And yet, only recently has the government acknowledged there may have been some civilian deaths as a result of their scorched earth policy of attack. The UN – who vacated their workers from the conflict zone before the war ended – has found both the government and the LTTE to be guilty of human rights abuses, but transitional justice has never been fully implemented. Discrimination, surveillance and censorship continue. And while the government does not acknowledge its role in the Tamil genocide, it is equally important to acknowledge the role of the LTTE in this loss. For while loss can be a catalyst for collective mourning, in the case of Sri Lanka its politicization continues to sustain competing visions of nationalism that underpinned the war in the first place. The politicization of grief in the aftermath of the war’s end is all the more painful and violent because it means that remembrance requires first working through the instrumentalization of loss, before even beginning to reach a place from which to build our memorials. In parsing, I find it hard to hold onto and center grief because each time grief overwhelms me. When I am overwhelmed, I have a tendency towards turning away and finding distance. And for me, experiencing this war and its aftermath has always been mediated through distance: grief is for those I do not know, for a community I left long ago, for a country in which I am almost a stranger. In these moments I cannot help but wonder: if I spoke my mother tongue still, would I be able to find some way of bridging this distance? Would I find a space to say those names who have been lost or speak the towns and villages erased, or find some poetry or song that framed this loss for me, in another private way? Speaking about his own relationship to Tamil, writer Anuk Arudpragasam has explained in interviews, that speaking English in Sri Lanka is a public marker of a certain status achieved and, maintained. It is a colonial language, a language I have had to move with in order to appear recognizable. I had probably started losing my tongue before I even began to speak. English is a language in which loss can become internationally validated in our western political landscape, making it both highly publicized and easily politicized. This would be the case, no doubt, whenever one is dealing with any language that is hegemonic. But when you no longer have any other language with which to probe an inner, unseen world of mourning, your memorialization must always and only take place in public, its validity dependent, so it seems, on being recognized.It is this relationship between public and private validation that acts of commemoration must mediate: a memorial creates the space for communal remembrance, threading what is expressed privately into a shared narrative. Without a physical place to perform these acts of public remembrance, official forms of language – and phrasing – also become significant markers. For example, in Sri Lanka civilian deaths are only begrudgingly underacknowledged by the Sri Lankan government as collateral damage, but they have no public space of remembrance, in the country itself. Tamil women continue however to sustain the public work of remembrance as they search for loved ones. Refusing government directives, these women create shrines and distribute posters that compel us to not forget. Tamil artist Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan has compiled an archive of living memories in his artist book The Incomplete Thombu. Re-using a Dutch word for land registry, his public registry is a collection of memories of home, drawn and recounted by the communities forced to flee from the Jaffna peninsula. The book is divided into drawings, topographical renderings of participant’s homes as they remembered them for many are destroyed and a typed narrative. Using the language of ‘accounting’ or accountability that underpins the competing discourses around the war – the need to prove or collect evidence that certain things happened and certain things did not – he transforms this bureaucratic violence into a receptacle that commemorates what has been lost. Shanaathanan’s act of storytelling, which is also an act of reclamation of the lost from the erasure of the official record, is itself a powerful form of memorialization in the shelter it provides for those displaced. Along with other projects such as Sareesinthewind and Stories of Resilience, these forms of storytelling also rewrite the narrative of Tamil survivors. The women, men and children who tell their stories voice their struggle and their perseverance: they are not merely victims. And so I think of these projects often as I contemplate what it is to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the end of the Sri Lankan war, without either a public space in which to come together with others, or the familial language by which to vocalize something like a shared memory. They are stories of women and men who have, as V V Ganeshanthanan also urges, refused to be defined by catastrophe, who have built, using what they have, their stories, a memorial to what has been lost. Their voices generously create space for careful forms of witness. Their stories urge us to continue the call for the restoration of Tamil civil rights and, particularly in this current climate of social and political unrest, to work against the cultures of violence and religious extremism that are tacitly ignored (or otherwise) by government administrations who continue to fall back on restrictive measures of securitization. It is from this space that I will be remembering the ten-year anniversary on May 19th, while I also begin the long and arduous journey to reclaim my mothertongue. Anna Arabindan Kesson was born in Sri Lanka but grew up in Australia and New Zealand. She was a nurse for several years before completing a PhD in African American Studies and Art History in 2014. She now lives in Philadelphia and is Assistant Professor of Black Diaspora Art at Princeton University where she writes and teaches about art, race and empire. Twitter @AnnaArabindan

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo 1: Parasakthy and Sundha 1961 in Colombo Photo 2: Parasakthy and Sundha in the 80s in Chennai Photo 3: Sundha as a BBC newsreader 1982 in London Photo 4: Sundha interviewing a young Mathematics prodigy from Tamil Nadu from Radio Ceylon studios 60s in Colombo Photo 5: Sundha was also a talented photographer, and this is one of the photos he took and cheekily edited on his film camera Photo 6: Sundha performing in one of the radio dramas, Radio Ceylon 1950s Photo 7&8: Front and back cover of ‘Mana Osai - Reminiscences of a Broadcaster’ a book about Sundha Paraskathy Sydney, Australia *note that uncle refers to Parasakthy’s husband, the late Sundharalingam. In 1948, uncle, as a young boy, had listened to the running commentary of Mahatma Gandhi’s funeral procession. Back then in Jaffna nobody had a radio at home, so the school principal hired one for the kids to be able to listen to Gandhi’s tributes. Uncle said that he and many of the children cried. Uncle was so amazed at how something happening in a distant land could move people in his village in Chavakacheri. In his wonderment at how this was possible, his dream to one day become a radio announcer was born. Sri Lanka started broadcasting in 1923, three years after Europe started the BBC. The transmitter was built using equipment from a captured German submarine. Colombo Radio, later known as Radio Ceylon, started broadcasting in English first and later added Sinhhalese and Tamil . As the station’s popularity grew in India, Hindi was introduced, which also catered for the Hindi-speaking businessmen in Colombo. While uncle was studying at Jaffna Central college, he stayed in a hostel and would listen to the 9pm All India Radio news on the public radio installed in Subramanian Park while the other students would be engrossed in their studies. At the age of 21, uncle started working in Colombo, having skipped his university entrance exam to earn money. There he found himself working in the office next to Radio Ceylon. One of his colleagues was a radio drama artist and invited uncle to join him. Uncle fell in love with the stage and soon became popular for his theatrical talents. When a vacancy opened up for a news reader, he applied and was appointed to the job. By the fifties, radio had become a big craze in Jaffna, but very few people could afford a radio and our parents also didn’t want us to get distracted by listening to film songs and dramas. Even if we could afford a radio, my family didn’t have electricity. We had a simple life and education was our main focus. Uncle’s family also didn’t have electricity and had to go to a neighbour's house to listen to his broadcasts. While at Radio Ceylon, he was seconded for a ministerial post as press officer with the option of returning to his job as a news announcer when he wished to do so.

His duties included reading the papers and giving the minister a summary of daily events as well as interpreting speeches from Sinhala to English or Tamil. He also accompanied different Sinhalese ministers on their trips, bearing witness to their acts incitement of discrimination against the Tamils. He would often come home and tell me how sad he felt. His next job was as a simultaneous interpreter in parliament, a service provided for the Members of Parliament . Most of the Members spoke only Sinhalese or English and uncle worked as the Tamil translator.

Because parliament only sat for a few days a year, uncle had a lot of free time, which he filled by voicing jingles for advertising companies and performing in radio plays .

The stage was like a second home for him. He had so much confidence in all three languages. In 1969, he and another interpreter were selected to do the simultaneous interpreting for the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20. These Sinhalese and Tamil interpretations, which were done non stop for three days, were broadcast by Radio Ceylon all around the country and region, capturing that awe-inspiring moment in history. The US Embassy in Colombo trained the team, which included Tamil and Sinhala scientists, for about a week, so that they were familiar with the technical terms. They also had to go through a simulated landing. Uncle found the American English difficult, but managed to successfully complete the task. Though Sinhala chauvinism escalated well before the eighties, we never imagined it would eventuate in the pogroms and violence that followed, culminating in the atrocities of 2009.

When the Sinhala Only Bill was passed in 56, uncle had to read it out as news on Radio Ceylon and had to cover stories of its implementation. Uncle was also a news reader during the 58 ethnic riots and the 76 and 78 pogroms.

Uncle's time at Radio Ceylon, his time in parliament and our years in India, the UK and Australia as a refugee during which time he yearned to return to our country of birth, had a profound effect on him. His resulting grief stayed with him right until his last days in Australia. In 1959, I graduated with a BA in Arts from Peradeniya University. My family never thought I would get a place in the university, as it was a difficult entrance exam. In those days, the results were announced in the English newspapers. But in our home, we only read Tamil newspapers. My father's friend saw the results and sent the paper to our home, with my name underlined, through another friend. I also had the option of entering a Teachers Training College to study teacher training, which required a less competitive mark than university studies. My school principal, the late Miss Thambiah, however encouraged me to enrol in university and promised me that I would have a job back at our school, Vembadi Girls’ High School, when I had finished my degree.

In Jaffna, education was mainly segregated into male and female schools. In certain schools, at the higher levels there was mixed education. So university was where I first met men, outside my immediate family. It was also the first time I met Sinhalese students. There were about fifty Tamil students and two or three hundred Sinhalese students. We enjoyed our single rooms and ate in a dining hall with fork and spoon. We were served a lot of beef and so I became a vegetarian. University is where I tasted cheese for the first time. Our education was free, and our living expenses were minimal. Those of us who remember the days of no ethnic divide, will remember university as a wonderful experience. Those days we had the best of everything in Sri Lanka - free education and free medical services. Everything was good, till the politicians of the majority community poisoned the minds of the people against the minorities living in the country. I think that now it's too late for change. The poison has sunk in too deep. After my studies, I returned to Jaffna and started teaching at my high school. I was so happy and I had many dreams of helping my siblings, who were excelling in their studies. But a marriage proposal to uncle came my way in 1961 and though I had a lot of ambitions and wasn’t keen on it, it was my parents wish and so I obliged. After our wedding, I joined uncle in Colombo where we had a comfortable life, like most middle class families. I got a job at the Muslim Ladies College in Bambalapitya Colombo. Teaching in a multicultural environment was another unforgettable experience. Our move to Chennai in 1980 was not my decision and nor was I in favour of it. Our only daughter Subhadra had just sat for her OL exam and was keen to continue her bharathanatyam studies, while we wanted her to attend university. It came as a rude shock when one morning in January 1980 uncle asked me to sign my retirement papers. He explained there was an option for lady teachers to retire after twenty years of service, which i had just completed, and I could avail myself of that facility. He said I could go to Chennai to educate Subhadra in the Fine Arts (music and dance), while at the same time help her to get a degree in Arts/Science. My school principal refused to endorse the papers as I was in the process of being appointed as principal of the newly built Colombo Hindu Ladies College. I was appalled! Who would throw away everything so good? I was in a dilemma but my husband solved it for me. He said “a decision has been made, let us not go back on it”. He said that Tamils couldn’t live in Sri Lanka in peace anymore and that political unrest was simmering. He said that he no longer wanted to live like a fugitive in his country of birth ‘his தாய் நாடு’ and that after translating the venomous speeches of the Sinhalese Members in parliament, he had spent many years of sleepless nights. He said that at least in Tamil Nadu we would feel a sense of familiarity and could continue to be part of the Tamil culture and language. He reminded me that we had to seek refuge in a Muslim friend’s house during the 1977 pogrom and that our daughter had no chance of entering university with the government’s standardisation policy which penalised Tamil students. So in Jan 1980 I retired and we left for Madras, our home for the next twenty years. There were only three other Tamil families from Sri Lanka who had settled down in Chennai after the first pogrom in 1958 and they all welcomed us graciously. Mr and Mrs Sivapathasundaram had made Adyar their home, the suburb which would become our home too. Mr Sivapathasundaram was a renowned broadcaster at Radio Ceylon and a popular Tamil writer on par with Indian writers. He was the one who gave the name Thamilosai to BBC Tamil Radio. We realised theirs was a life of struggle even after spending nearly three decades in Tamil Nadu. Our years in Chennai were also tough, and those who came to visit us were shocked to see how we were living in a single room annex. In 1982, we received a surprise phone call from the BBC asking uncle if he would come and work as the Tamil radio producer for one year, while Mr Shankaramoorthy, the then producer, took one year of medical leave. In uncle’s previous trips to the UK he had acted in some of the BCC Thamilosai’s radio dramas and so they were familiar with his talents. Subha had entered Stella Marie’s College, so we put her in the college hostel and set off on our year long UK adventure. We could have stayed on after our contract was over by taking part in radio programmes, however uncle said that he wanted to listen to carnatic music and hear Tamil in his ears - காதிலே தமிழும் பாட்டும் கேட்கவேணும் ! So after our stay in the UK was over, we flew straight to Colombo, with the hope of settling back there. After about 10 days of visiting our families in Jaffna, uncle, again said that he felt something bad was going to happen and he wanted to get back to Chennai. I again didn’t want to leave. I missed our family and they missed us. We had nobody in Chennai. Uncle however insisted that we had to return to see our daughter Subha and once again said “I don’t want to be a second class citizen in my own country”. We arrived back in Chennai in May 1983. In July when the pogrom against the Tamils started in Colombo, those who had money, got on planes and arrived at our doorstep. Over the following six months, at least a hundred Tamils made their way to our home straight from the airport. We helped them find temporary accommodation to begin with, then a home and a school for their children. We became local guardians to hundreds of children, as this was a government requirement. There were number of challenges we faced as guardians - illness - exam failures - two missing students - but we were thankful we could help them. Those who could afford to sent their children to other foreign countries. Thanks to the BBC, we had a telephone, which became so useful for the many Eelam Tamils who would line up outside and inside our home to use it. One night, we had more than 20 people sleep in our tiny annex. Those nights were tough, but what were we to do? Uncle, who looked to life’s positives, would often tell us that he was grateful that we got out in time and didn’t have to go through the trauma of watching our people being massacred. He was even more thankful that we were in a position to be able to help those that did escape. After hearing of the massacres and the burnings of the 83 pogrom, the people of Tamll Nadu became sympathetic to our cause and opened up their homes for rent. MGR, was the Chief Minister at the time, and said all Eelam Tamils could be accepted into schools in Tamil Nadu. For those who didn’t have money and escaped the island by boat, they were kept in refugee camps in Tamil Nadu, and their plight was and still is an incredibly sad one. Many are still there with very little protection or hope for a better future. We were the lucky few and though we never returned to live in our country, we have a lot to be thankful for. In the years that followed, uncle became BCC’s Thamilosai correspondent for Tamilnadu, which allowed us to continue living in the India and provided us with a permanent income. Thanks To BBC, we were also able to get a visa to visit our daughter in Australia. After uncle passed away in Australia after a tragic accident in 2001, I did not want to go back to India and all my family members had left Sri Lanka by then. I stayed on with my daughter's family as a refugee for 12 long years. It was a period of struggle and great uncertainty, thanks to the Australian government. I was finally granted Australian Citizenship in 2017. END In 1999 Dr Maunaguru, a close friend, turned audio recordings by uncle about his life into a book titled ‘Mana Osai -Reminiscences of a Broadcaster‘. Uncle was not keen on the book idea, but he agreed on one condition that the book when published would be distributed free - he said everyone has a story to tell so it's not fair to make money off it. Aunty’s grandson Senthan is now also a radio broadcaster and co-hosts the popular podcast Stuck in Between.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

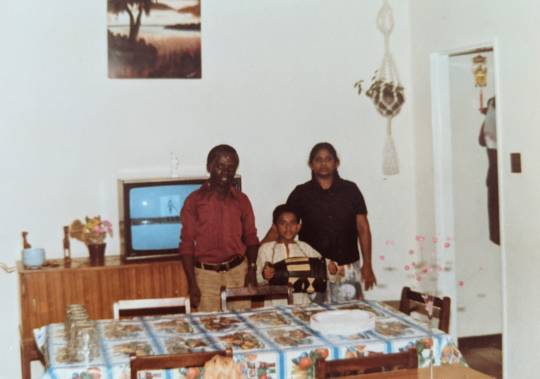

EELAVAN [Location withheld]

Photo 1-3: The mountain in the final paragraph Photo 4: The rock in the final paragraph Amma and appa were always away on duty during the short years I shared with them. So, I was raised by my amma’s acca. My life’s happiest moments were the brief periods spent with my ammah, when she would visit me. In 2006, amma left me with a neighbour P*, because my aunty and her family left to seek asylum abroad. We didn’t have any other relatives to help us. My amma may have had an anna who was in the Iyakkam. I don’t know much about appa’s family. My acca was also in Iyakkam. I am not sure how many years older she is to me. I don’t even know my own age.

After I moved in with P*, I would often join other children in the neighbourhood who would gather at the home of a family who owned a TV. We would watch the serial ‘My dear bootham’ and the news. This is where I first dreamt that one day I would become a news reporter - so I could tell the world what was happening to us. I loved reading and I loved history. I once found amma’s book on Lenin, and I tried to read it, only understanding a few bits. I liked reading with my amma.

In 2007 when the attacks by the Sri Lankan Army started intensifying, amma pulled me out of school. When displacement started, P* took me with her. I remember a time when amma came to see me after she had been injured and had a bullet wound in her right shoulder. Then too, I cried and begged her not to leave, but she said her team would look for her and she had to go.

Appa’s last visit to see me was in Jan 2009. In March or April, amma was with me and P* when we found out that appa had been killed. An Iyakkam anna came to tell her the news and explained that they couldn't retrieve the body because the Sri Lankan Army had taken control of the area. Amma cried, as I hugged her. She didn’t eat for two days. Iyakkam accas came to console her. We put up a photo of appa and lit a fire in front of it. That evening a jeep came and she left in it. The last time I saw her was on May 10 2009 around 2pm. She put her gold ring on my finger and asked me to keep it as a memory of her. I cried and begged her to stay. Over the years I have tried to find out what happened to my amma and acca - no one can tell me anything. Not knowing what happened to them is my deepest unrelenting and unimaginable sorrow. On May 14 2009 at around 6pm, N* came to where I was staying with P*. He said something to her and we left together. At around 10pm he took me to the ocean and put me on a boat with four iyakkam accas and six iyakkam annas and he told them to take me to X* safely. The annas and accas were carrying bags of paper. Thinking back now, I think they were important documents. To keep us safe, two other iyakkam boats accompanied us - and at some point those boats returned back. The annas and accas told me that we would be safe. Suddenly our boat was surrounded by many little boats - it was the XY* navy and they told us we had to turn around. We were soon approached by people in a boat who were speaking Sinhalese. The annas and accas were forced out of our boat and into the Sinhalese boat. Their hands were tied behind their backs and their eyes blindfolded. All the documents were moved into the Sinhala boat. I was taken by the XY* navy and delivered at X* at around 3am. Before letting me go, the officer warned me never to speak about what had happened that day. The people at X* were scared that I was going to bring danger to their lives. I was asked to leave and was soon out on the streets. I didn’t eat for two weeks. My journey since then has been one of enormous hardship, suffering, and loneliness. In 2017, I attempted to study journalism at college, with the little money I had managed to save. However I could only afford a course in Hotel Management. Not wanting to delay my studies any further, I enrolled in it. We were trained in many skills: front office, service delivery, production department. For me, enlisting in production department classes also meant I would be able to eat a proper meal, something that I hadn’t experienced since a young age. Over the years, many of my meals have been bread scraps discarded by bread companies. Many nights have been spent sitting in railway stations. If we sleep - the police would beat us. I would buy a ticket, and stay on a platform for a few hours at a time.

I faced a lot of discrimination for being an Eelam Tamil when I was at college. Even there, I was isolated and alone. In one of my classes, my teacher called me the child of terrorists in front of all the students. It was so hard for me to experience this, but I was still determined to complete my studies. I had one female friend for a little while. She would ask me for my notes and recipes and I would openly share them with her. I asked her if she would be my life companion. Her response was to ask me how she can accept a terrorist's son. This really hurt me and I decided that I was better off without anyone in my life. I learned to cook a lot of different dishes at college and won many awards in recognition for my talents. At the four-star hotel, where I did my training, we would work 18 hour days. After I finished my placement, the manager at the hotel wanted to give me a job. However, as I am unable to obtain official work permit documents, such opportunities will never be for people like me.

I now work in a tea shop - 7 days a week from 5am to 10pm. I earn 6.20 AUD | 3.50 GBP | 4 EUR | 4.80 USD / day. I sleep in the back of it. Sometimes I don’t even have time to eat dinner.

In August last year, when I had to cross a border checkpoint, the police found amma’s ring and the little money that I had worked so hard to save, and they stole both from me. Through my hardest times, I had her ring with me, and now I have lost that too.

I can’t speak the language here and I have no friends. When I get a day off once every two months, I spend it at a nearby mountain, where no one goes. Even mobile phones don’t get a signal up there. It takes about three hours to walk up to the top. I sit there and I think about my life - and wonder what type of future I can hope for. I pretend that a rock up there is my amma - I ask her questions about her life and ask her where she is. I share my feelings with her. I cry a lot. I feel completely stuck and unable to make any decisions, as I have nothing or no one, or no place in which I can feel safe. I start walking back down at 4pm and arrive at the bottom by 7pm. On those nights, I sleep a little better. P* - name changed to protect identity N* - name changed to protect identity X* - location withheld XY* - name withheld

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

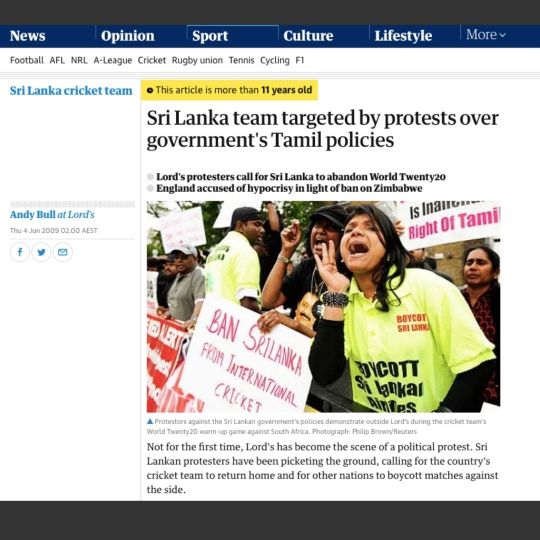

'SRI LANKA STOP KILLING TAMILS' JEGAN Australia

It has always been near impossible to get the international media to cover the Sri Lankan government’s violence against the Tamils. In the late 90s, as the atrocities escalated, the world was more interested in celebrating Sri Lanka’s cricketing heroes than exposing the Tamil genocide.

Early in 1999, when the Sri Lankan cricket team played in the 1998–99 Carlton and United Series in Australia, in utter desperation at the world’s silence, we hired a skywriter to write “Sri Lanka Stop Killing Tamils” above the Sydney Cricket Ground during one of the matches.

The decision to do this was not an easy one. There was a view that our fundraising efforts should be sent to those affected by the war in Eelam. This was a valid concern, however, it was also an important opportunity to put Sri Lanka’s crimes on the international stage.

The total cost was $7000 AUD. We found 25 sponsors to donate $100 for each letter. A few businesses and individuals covered the rest. We fundraised specifically for this campaign.

While I was worried that we would be in trouble with the police, the skywriter didn’t seem too phased.

The plane started writing around the time the game started at 2pm. We were lucky that we had clear blue skies with no winds to scatter the smoke. It was impossible for anyone watching the cricket to miss the white letters which stood out prominently against the blue. The pilot told us that the height of each letter was 1km and the width was 750m.

During the time of the skywriting, I was in a car with another activist near the SCG watching anxiously. Within 10 minutes of the writing ending, we received a phone call from an overseas number. We nervously picked up the phone, not sure what to expect. It was the co-ordinator of the diaspora Tamil activists and he praised us for our creativity in putting the violence against the Tamils on the international stage. His support gave us a bit of confidence that the large amounts of money we had spent were justified. A few days later there was another match in Melbourne and the same message was written there. A news outlet that covered what happened in Australia, and it was our then spokesperson who spoke to the journalist who covered it. She said that the journalist had asked about the cost. Our spokesperson explained that while it was a lot of money, it was one of the ways our community could try to raise awareness, given that the media was not interested in covering the violence. ****** We have not been able to track down any photos or find out which news outlet covered the action. * In 1984, a year after the Black July pogrom, when the Sri Lankan cricket team was at Lords in London for their first test match, Tamil protesters ran onto the field with banners and lay on the pitch. You can watch the footage here. * In 19 May 1999, UK Tamil activists skywrote "Killing Tamils is just not cricket” while Sri Lanka was playing against South Africa at the County Ground. * In 2011, a yellow weather balloon bobbed up above the Lord's pavilion in the UK. It had "Boycott Sri Lanka" scrawled on the side in thick black ink. * In 2012, Trevor Grant, a former chief cricket writer at The Age called for Australia to boycott the Sri Lankan cricket team. Trevor became an unrelenting champion for Tamil justice and become an active and vocal member of the Tamil Refugee Council and a close friend to many of the Tamil activists. We lost another selfless soul, when he passed away in 2017.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo 1: Thavamany and Arunachalam on their 25th wedding anniversary,1965 Photo 2: Thavamany at 95 years old, 2015 Photo 3: Thavamany with her youngest granddaughter Luxmi who lives in the UK on her 18th bday, 2016 Photo 4: Thavamany with her great grandchildren Sasha and Ziva, and their appa and her eldest grandson Sajith, who live in in Hong Kong, 2016. NAREN Florida, USA My amma, Thavamany, was born on the 23rd of April 1921 at Inuvil Hospital, Uduvil Division in the Jaffna District. Her appa’s name was Thambu Chinniah and he worked as the Superintend of Minor Roads in the Kurunagala District.

At that time wild elephants were in plenty in the Kurunagala District and would harass local farmers. Thambu Chinniah was a good marksman and villagers would often seek his help to track the elephant and shoot it dead. This reputation of his overtook him and he was also known as “யானை சுட்ட சின்னையா” (Chinniah who shot the elephant). Thavamany’s amma’s name was Marimuttu Chellamah.

My appa was the fifth child. She had two elder sisters Poomani (Ponnudurai) who was a housewife and Jeyamani (Brodie), a Government nurse as a spinster, and a housewife subsequent to marriage. She had two elder brothers Selvarajah, who retired as a Major in the Sri Lanka Army and Dharmalingam, a lawyer who practiced in the Kurunagala District Court. Her younger sibling was Rajadurai, who retired as chief mechanical engineer at Gal Oya Development Board. Rajadurai was also a Major in the Sri Lanka Army Volunteer Force.

When Marimuttu Chellamah was eight months pregnant with Thavamany, she fell into a well while bathing. Back then the wells in Kurunagala had wooden planks on their rims. People would stand on the planks and draw the water with a rope and bucket. Ladies, when bathing, would wrap part of their sari around themselves and leave the other part on the wooden bars. On this said day, after drawing four buckets of water, the plank gave way and Marimuttu Chellamah fell into the well. Luckily her sari got entangled on the wooden bars and held her from going under water. Hearing her screams, the neighbors rushed to her and pulled her out of the well by her sari. That day Thambu Chinniah was away on work-related matters. He got the news three days later and rushed home with worry. When he opened the door, he was relieved that his wife was their soon to be born daughter, my amma were safe and healthy.

A humorous side note: if Chellamah had not been saved by her sari, I, her eldest son, would not be writing this and my amma would not be enjoying the excellent care she has been receiving at Jesmond Nursing Home in Sydney.

Sadly, Thavamany lost her appa when she was eight years old. After this, Chellamah left their home in Kurunagala, and moved to Jaffna. She found a place in Clock Tower Road in Jaffna Town. Chellamah was a very determined and industrious lady. She was also very determined to educate all six of her fatherless children. She managed to admit all three of her sons to St. Johns College in Chundikuli and the three girls to CMS Chundikuli Girls School. Chellamah being a strict disciplinarian made sure her children successfully completed their Senior Matriculation Examination - equivalent to the present day Senior School Certificate.

Chellamah earned money to raise her children by having a couple of milking cows. She supplied unadulterated milk to all her customers, including to the residence of the then Government Agent of Jaffna, a British Officer. She was famous for her cooking skills. The family had very little money, but she was rich in kindness and compassion and brought up her six children with these values and an understanding unity. They remained united until their last breath.

Thavamany helped her amma in so many ways: cooking, organising the milk supply and keeping accounts. When I was growing up, she did impart most of her knowledge and experience to me which helped me a lot in my later life.

Thavamany married Arunachalam, my appa, in May 1940 in Kurunagala. At that time Arunachalam was working as a bookkeeper at the State Mortgage Bank in Colombo. Arunachalam lost his parents when he was child. St. John’s College, founded in 1823 by British Anglican missionaries, provided him with free board, lodging and education. He was also christened with the name Abraham. He was a good friend of Thavamany’s three brothers who he met at St. John’s College. Arunachalam served in the Ceylon Army Volunteer Force during the Second World War for a short period .

Arunachalam was also a hard-working and industrious man. Subsequent to his marriage he attended evening classes at the then known Colombo Technical College and obtained his Diploma in Accountancy. This helped him in his professional career and when he retired, he was the chief accountant at the State Mortgage Bank.

After their marriage, they set up house in Hunupituya, Wattala, about 10 miles north of Colombo. As the family expanded, they moved from one house to another and finally settled down in a reasonably spacious house to accommodate their seven children. The house also had a large yard with coconut trees. This allowed appa to have two milking cows and some banana trees. Amma in addition to being a housewife and mother, cared for a couple of goats and some poultry, which provided eggs for the family. It was tough for the couple who did not have any dowry assets or inherited assets. But by sheer hard work and frugal living they made sure all the basic needs of the children were met and provided the children with a good education. They also made sure to teach their children good social values, good manners, to be respectful to elders and all other human beings. Since they also had cows, goats, poultry and dogs, they also taught the children how to care for them and be kind to them.

Most of the residents in Hunupitiya were middle class Sinhalese Buddhists. Because of this amma and appa picked up the Sinhala language as did we, her children. Thavamany, an observant and willing learner, became very proficient in preparing most of the Sinhalese specialty dishes like achcharu, kalu thothal, lunu miris, katta sambol and few others.

When the 1958 pogrom started, appa was away in Omanthai, Vavuniya and could not return back, nor could he make contact with the family. We didn’t even know if he had survived. Thavamany and her six children (I was not with them as I was in Jaffna Hindu College Hostel) sought refuge at the Royal College in Colombo, which had been set up as a refugee Camp with thousands of other Tamils. Amma made the brave decision to secure her children's safety by joining the Tamils who were fleeing the south by open boat to Jaffna. As a woman with three young daughters and a baby only a few months old, in a time of such uncertainty and violence, this would have been an incredibly tough decision to make. We had no family property in Jaffna, but she had her siblings and extended family who showed us love and kindness.

This caused a big setback to the family. We had to close down everything in Hunupitiya, set up house in Chavakacheri, and attend new schools in Jaffna. During this difficult period appa continued to work at the State Mortgage bank in Colombo. He was boarded in a house in Pickering Road Kotehena. Most Fridays he would take the mail train from Colombo Fort Station and arrive in Chavakacheri on Saturday Morning. He would return back to Colombo taking the Sunday afternoon Yaldevi.

Amma continued to develop her Sinhala skills by reading books and studying with her children, as she stayed up with the girls, into the late hours of the night. At 41 years of age, when her second son sat for his Senior School Certificate (SSC) exam in 1962, she persuaded my appa to let her sit the SSC Sinhala language exam as a private student. She received a Distinction - the highest mark for the Sinhala language exam among all her children.

In Chavakacheri, a few youngsters heard about amma’s fluency in Sinhalese and were keen to learn from her, as finding jobs without knowing the language was becoming tough. Understanding the importance of her knowledge and the difficulties the young Tamils were in, she taught anybody who was willing to learn. As a result she had a regular stream of students who learnt Sinhalese.

Wanting to give the children the opportunities to have a good education they moved houses to Jaffna Town, then to Nallur and finally Tirunelveli where they owned their first house.

By this time most of the children completed their education, finding employment - some locally and some overseas.

Thavamany’s children settled in three different countries: the UK, America and Australia. She and appa travelled to various countries and stayed with their children for long periods of time.

Appa passed away while living with my sister Thevi and her family in Zambia on 2nd of August 1987. Although scattered all over the world, all seven of his children attended his funeral in Zambia. After his death, amma settled down in Australia with her three children. She was fortunate to be able to spend quality time with all her grandchildren and some of her great grandchildren who would regularly visit Australia and spend many of her birthdays with her.

Amma was a big fan of Swami Vivekananda. She was also very religious and practiced her spirituality without talking about it or enforcing her will on others.

One of her noble traits was patience and acceptance without complaint. She would often tell her children “பொறுமையாய் இரு. பொறுத்தார் அரசாள்வார்” (Be patient, for those who wait will rule the world).

*This story was written early in 2020 by Naren, Thavamany’s eldest son. Thavamany passed away in her sleep on 22 October 2020 with her daughters and granddaughter by her side. She had spent her last years at Jesmond Nursing Home in Sydney close to her son, two daughters and their families. She was loved and cherished dearly by all who knew her.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Photo 1: Thevy, Sri Lanka, 1974 Photo 2: Thevy at home in Zambia with her son B and Leonard Banda Photo 3: Thevy and her son B visiting her anna Jegan and his family in Tanzania,1984. THEVY Australia Our brief time in Iran was at the time of the 1979 revolution. Our son, B, was only 18 months old when he and I joined my husband (referred to hereafter as uncle) who was working as an engineer in Bandar Abbas, on the southern coast. It was the first time B and I had left Sri Lanka. Uncle had sent us a msg to not get on our flight out of Sri Lanka, because it was too dangerous in Iran, but in the chaos of trying to organise our visas and departure, I missed this memo. Life was tough for everyone. Food was in short supply, as was gas. We lived in a small flat for company staff. We often heard gun shots from the streets and it was made clear to us, more than once, that as foreigners, we were not welcome in Khomeini’s Iran. Uncle wasn’t able to leave the house to go to work shortly after we arrived because of the civil unrest, so for the remaining six-to-eight months that we were there, he stayed at home and would only leave if we had to buy food or for emergencies. I had to stay inside with our son the whole time. We had a very small group of friends that uncle had met after he arrived in Iran, to lean on and sometimes share our meals and shopping trips with. However I was the only woman in the group. Realising the dangers we were in, Uncle’s boss offered to help us leave the country as the airport had been shut down. Uncle’s boss drove us in his car via a jungle route to the port. We had to stay off the roads to ensure our safety. From there we got on a cargo boat to Dubai. It took 20 terrifying hours to cross the Persian Gulf. There were about 20 others, mainly from India, travelling with us, but I can’t remember if we were spread across one or two boats. To protect my little son from the anger of the ocean, I stayed with him inside the deck the entire time. There was one other woman in the group and she was pregnant. Our next challenge was in Dubai. We were not allowed to disembark because we didn’t have a visa. I had brought powdered milk for our son, B, which we shared with the others. Some of the men went to the Indian embassy and negotiated with them to allow us to travel to the airport and get flights back to our countries. Eleven hours later we were given this clearance. However, our family found itself in trouble again, because we had purchased our ticket to Sri Lanka on a Singapore airlines flight using Iranian money, which the airline would not accept. B had been suffering from seasickness and had been vomiting on the boat, and so to pacify him, I told him that I would buy him a helicopter when we got off. I bought him one at the airport, which kept him occupied and happy. At around the 18 hour mark, two Singapore airline pilots walked past us and our son caught their attention when he called out ‘uncle’ to them’. They kissed him and asked us where where we were going. The pilots were on their way to Sri Lanka and kindly arranged for us to get on their flight. Our friend picked us up from Bandaranaike Airport. We had a nice meal, shower and sleep at his home in Colombo and the next day we took the Yal Devi (train) to Jaffna. My parents were no longer there as they had left to join my elder brother in Tanzania and all my siblings had also left the island. So we rented a place and stayed in Jaffna, unclear again of our next steps. We knew that finding a job for my husband was going to be tough, and that we had to look for opportunities abroad. We left the country six months later in February 1980 and made our way to Zambia, as uncle had been offered a job there in a copper mine. The company paid for our tickets and provided us with a home in a gated colony for workers of the mine. They also ensured that we had food for a few days. There were food shortages in Zambia and so those that were already helped to ensure the newcomers didn’t have to worry about sourcing food. B made friends with the four children of our domestic help, Leonard Banda, and so immediately settled into his new life. B was thrilled to celebrate his 3rd birthday with them. We communicated with everyone in English. For B’s 4th birthday, we wanted to share his cake with others who were not as fortunate as us and so through a friend, we learnt of a school in Luanshya for children with disabilities. A week before the date, I started explaining the situation of the children to B and why some of them may have certain disabilities. I explained to him that he would need to pour the ‘jolly juice’ for the 65 kids - a duty he happily performed on the day. I made a cake in the shape of a chess board and chess pieces and we had a wonderful day with the children. I was so happy to see B and the kids enjoying their time together. It was there that I realised I was in a place where I can, with love, support those around me that are not so fortunate. After this date, I would encourage friends in Zambia to donate a meal or two to this school as a way to honour deaths of family members back home and some of them did just that. I started doing community volunteer work. I set up a tutoring class in one of the local churches and taught basic maths and English to children who attended. There were about five or six Tamil families and about 15 or so Sinhala families who were working in the copper mines in Luanshya. Other workers and their families were from India, Philippines and Sri Lanka. We didn’t feel lonely because all those working in the copper mines lived together in a colony. During the weekend we often gathered at each other’s homes for parties. We are still close friends with one of the Sinhala families we met there. We were very fortunate in many ways, however I did find it tough there. As women, we did have to sacrifice the opportunity to work and to study. Women were not allowed to work unless they were professionals like doctors. In Jaffna, women had the freedom to study new skills and be independent. My two dreams had been to get a Diploma in Home Science at Lady Erwin College in Madras and to study carnatic music at Annamalai University. But my family couldn’t afford my university education and so I started working when I was 19 years old. When B started schooling, a dear friend, who knew I was struggling with not being able to work, asked me if I was interested in doing volunteer work as a bookkeeper at the Luanshya Golf Club. I was delighted to be offered the opportunity! I went there daily and learnt new skills and took on quite a lot of responsibilities. As a thank you for my efforts, I was given local currency which I used to buy a gold bangle which I still wear to remember my years in Zambia. The company gave us a ticket to go back to Sri Lanka once every three years. During those trips back home, I made sure that I would bring back all the spices that we would need. We could purchase them in Zambia however it was an hour or so away from our home. My appa joined us in 1987. He was 76 years old. He had been living with my anna, Jegan, and his family in Malaysia in the few years prior. Appa quickly settled into life in Luanshya. He became a popular figure with the locals. When I took food for the elderly people at the Home for the Aged, he would join me and help me pack food. My dearest appap passed away while he was with us in Zambia. My amma, on my insistence, had arrived just a few days prior to his death. I had an intuition that something was going to happen to appa, which is why I pushed for amma to join us from the UK. She had been living there with my other siblings. All my six siblings attended appa’s funeral as did much of Mufulira. After twelve years in Zambia, we migrated to Australia.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

PRIYANKA We grew up with two knives. A triangular one that was used to descale and debone fish and a large rectangular one that Amma used to beat a chicken carcass into oblivion. If that bird wasn’t dead to start with, it was soon hacked into realisation. Kitchen cupboards were lined with empty Vegemite, Nescafe and Cottee’s jars and had scrawled labels in mismatched tongues: cardamom, மஞ்சள், கிராம்பு, cinnamon, ஓமம், மிளகு, வேப்ப தூள், கருஞ்சீரகம்,, நீண்ட மிளகு, சீரகம், வேப்பெண்ணெய் (this stuff tastes like HELL, in case you’re wondering - Thumby and I got a dose after swearing at each other😅). Amma’s was a kitchen that had all the things to make an excellent rassam, payasam or curry but limited when it came to cakes. Baking, a symbol of status and class, allowed no room for error. The six items needed for a simple butter cake were costly and rare. Electricity, non-existent during the interruption of war, meant that batter was hand-mixed, requiring patience, stamina and many hands to take over once the matriarch wore herself out. This was then taken to the local bakery and finished off for a small fee. வெள்ளைs, Christians (who learned from the வெள்ளைs) and Burghers are often referred to as the ones who knew how to bake, while the rest stuck to local, more communal cooking events: nelli crush, tomato jam and nelli jam. When army-imposed curfews came into place, folk got creative, steaming batter in idli thaachis or in makeshift ovens. Growing up, the only time we had cake at home was if Amma was baking for a special occasion and usually for someone else. Perri Amma made all our birthday cakes extra special by adding cocoa. She was from Kandy, knew how to frost a doll’s skirt like it was 1989 and ice Mickey Mouse’s eyes without the added cost of Smarties. Imagine the Caucasity of someone questioning where your spatulas were? Imagine going into a வெள்ளை kitchen, yanking open the pantry door to find a lone, dusty tin of Keen’s Curry Powder, no வெந்தயம், but six pairs of serving tongs. Imagine baking a cake with your Amma and eating it too.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

PULLIARASI In the distant she could hear the birds chirping, in their musical tones teasing ones ears with two toned ballads. The atmosphere was wild yet calming. Crisp and cool. The peacock squawked its unattractive, yet distinct melody. It was said the peacock sang at the sight of humans. Was the enemy approaching? Puliiarasi straightened her spine. It was 4:45 am, the perfect time to dose off into a dream, in your swaying your hammock on a tropical island with serenading birds. But it was more perfect for the enemy to pounce, use your lapsed vigilance to flank you, smoulder your dream and your entire team. You were responsible for their unsettled sleep, night after night. Soon they would need to be awakened. Puliiarasi was relieved. She had kindled a small, discreet fire in the corner of their little patch. She was rationed two matches per day, and the weather had been windy. With no kerosene to stoke the fire, she relied on bits of plastic and cardboard she found lying around. She arranged the pieces one on top of the next, with just the right amount of breathing space to allow for the oxygen to swim through and let the flames dance. She placed the dry coconut tree mesh that they had collected on top. It was called 'panadai' (பன்னாடை). பன்னாடை was also an endearing term to mean useless. But Puliiarasi always reminded those that called her this in reference to her clumsy ways, that it was this same useless பன்னாடை that they would rely on, in the drowsy hours of the morning to give them the spark for a delicious, warm and creamy sweet tea. She found some twigs in the adjacent woods that felt safe enough to venture into. Holding the rifle in one hand, cocked and her finger on the trigger, she hastily found medium sized branches that would heat up quickly but not smoke too much. Enemy drones were buzzing above, like an incessant mosquito swirling around looking for blood to suck. She prepared the tea, soaking the dusty leaves in a pot and then poured it through a strainer made from a small piece of t-shirt rag. She mixed the precious milk powder with copious amounts of sugar, a necessary step to ensure the milk didn’t clump when mixed with the concentrate. She poured out the sweet syrup milk tea into the nine metal tumblers, and walked each over to her sisters, her lifeline, her protectors. Without them, she would not be. She nudged them with the butt of her rifle, a few startled awake, as she woke them up from their dreams of being manhandled by army men. She smirked and gave a sigh of relief. It was a mean joke, but one to play in their precarious existence. It also was a reminder to stay vigilant. Tomorrow they would keep a watch over her. Tomorrow, she would be the one being nudged, hopefully by a comrade rather than by the filthy hands of a perverted army troop.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Photography: Vinsia Maharajah @vinsia @vinsiamaharajah (instagram) ABHIRAMI (they/them) I grew up in Scarborough, born and raised in a community that is often viewed by people outside of it as the heart of all things diasporic Tamil. I was always surrounded by Tamil people through family, friends, during higher education and even throughout my professional life. And in many ways, it has been a privilege to be so connected to my cultural identity, but in many ways it was also a hindrance in my growth as an autonomy seeking being who was coming into a new understanding of myself. I was quite young when I first felt queer desire. I tried my best to make sense of a truth that was unfolding within me. I tried to ask my elders if there were gay people in Tamil Eelam. They would tell me ‘no - they were shot and killed’ or ‘they were sent away’ or ‘no - only white people do that’. Not having any facts to back this claim, I ingested what they told me and I carried it through my adolescence. It was clear that cisgender straight people did not have capacity to make space for us. Despite having historical records of our existence predating colonization, the erasure of queer histories was deliberate and in my opinion was also a form of sexual violence - when our sexuality has been queered, made queer and othered and marginalized through a white colonial lens. I didn't understand what liberation meant if it wasn't liberation for all Tamil people. Very early on I started asking myself – ‘I'm Tamil, but does this liberation include me?’ Queer Tamil more people are constantly having to ask themselves this exact question.

Where do we fit in the narrative - when so many of us need to erase our queernes to be present in these spaces? Are we also not worthy of liberation? What does liberation look like when it comes in many folds and your existence intersects with multiple marginalized identities? Who are my queer ancestors? Am I the only queer Tamil person? What's wrong with me? Despite all these questions, I kept it to myself because there was no one I could go to for the answers. There were no books, no resources, support services, family or friends. I did what many queer people do - bury those questions deep inside because we weren't ready for what we would have to face if these questions were asked out loud. My father left when I was 16 - a man consumed by world of trauma. He departed to take care of himself and although I resented him for so long it was not until very recently in my life that I was able to thank him for the choices he had made. This rupture in our family structure became an opportunity for me to envision a new future for myself - one that was not strapped to generations of oppressive expectations, but one where there were new possibilities to explore and make sense of something that didn't for so long. In some sense I felt liberated from the patriarchal vellalar supremacist respectability politics that suffocate and ultimately kill so many of us. This rupture didn't mean I was broken. It meant that I was finally breaking open for the first time. As I explored this new side of myself, I learned quickly that even in queer spaces something just didn't feel right. My queer exploration happened in pan South Asian queer spaces. When I was often times one of the only Tamil bodies present in the room, it became clear that this space was also not for me. It was the space occupied mainly by cisgender gay upper caste light skin Hindi speaking men who loved Sri Lanka because of how beautiful and peaceful it was. It was clear I was not going find my community in those spaces. I constantly found myself having to navigate erasure in some form: eraser in mainstream white queer spaces as a racialized body - erasure of my Tamil identity in South Asian queer spaces - erasure of my queerness in Tamil spaces. All I wanted was somewhere to feel whole. It took me years to finally find the queer Tamil family I was desperately yearning for my whole life - family that I didn't need to explain the various aspects of my identity to - family that I didn't need to describe the pain and the trauma and the loss too - family that supported my dreams and aspirations no matter how absurd they sounded - family that believed so deeply about possibility.They were my chosen family. In this new family. I also learned that rainbow capitalism is simply not enough. Although liberal politics will have you feel the Canada is a safe place for queer people - queer Tamil people, and more specifically transgender Tamil people continue to be violently shoved into the fringes of our own community. Living in poverty with limited access limited to no access to housing support employment and food security, transgender young people continue to have to find ways to support themselves. As vellalar Tamils build koyils and community centers to prove their prosperity, I think about all the Tamil people, specifically queer Tamil people who are left behind not just in the West but on the island also. There's more we need to do to support our community because we're failing many right now. As I re-enter political spaces, I no longer ask for the consideration for queer and transgender people - I demand it. We are not after thoughts or off tangent conversations- we are not secondary to that of the cisgender straight community. The analysis of caste, queer and feminist politics has to be integrated into every single aspect of this movement because the personnel is political. This is a reclamation of space for people who continue to be violently left out as queer people, Muslim people, caste oppressed people, peaceful people, people living with disabilities and generations of trauma. Although this may not seem possible when we look at the history of this movement. I believe it can be. I believe in the evolution of movements. I believe a movement is living and breathing and a growing entity. I believe in growth by means of meaningful integration of analysis that refutes capitalist elitist white supremacists and western imperious ideologies - one that centers the voices of the marginalized - one that has no space for toxicity or bigotry - one that makes narrow-mindedness obsolete - one that abolishes cash and gender-based violence because as Priya Thangarajah would say - If we're going to break the chains we're going to break all the chains. If it means unravelling everything what we know to build something towards a better future rooted in community and solidarity then it must be done - not just for Tamil people but for all people who are being crushed by these oppressive systems. I'll leave you with a quote by Marsha P. Johnson one of the foremothers of the queer liberation movement in the west and one of my queeroes - There will be no pride for some of us without liberation for all of us. *** This is a transcript of a speech that Abhirami gave at the Queerness and Tamil Identity webinar hosted by PEARL. Abhirami’s speech starts at 1.03.30

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MUTHUKUMARAN’S DAUGHTER This article was published on Oct 24 2009 - 11 years ago.

This is the first interview அப்பா gave when he returned home to Australia after surviving the genocide, escaping from Manik Farm incarceration and hiding in safe-houses. I can’t remember the exact date he returned. It’s all a blur now. But it was somewhere within two weeks of this being published. We knew there would be retribution from the Sri Lankan government for anyone that spoke to the media. So we convinced அப்பா to use a false name and not show his face. அப்பா unwillingly relented - for us. We then had to find a journalist that we could trust to protect his identity and his story. 11 years ago, this was all quite terrifying to navigate. Back then my (our) only experience of how journalists had portrayed the Tamils was as “terrorists”. A sequence of events had introduced me to a kick-arse comms strategists (now a friend) who heard our story and was disgusted with the international community’s response and he wanted to help. He introduced me to Drew. AB and I met with Drew in person and we talked him through what had happed in Mullivaikkal. He agreed to write அப்பா’s story as an exclusive. What this means is that he would get the first interview with அப்பா. I said I would only give it to him if I had the right to see the story before it was printed. For anyone who works with journalists, you may know that it is extremely rare that this would be agreed to. But I was so terrified and AB gave me the confidence to not compromise on this request. Drew agreed. The below is the text of the article. 11 years ago. It feels like yesterday. We learn to live with the pain, the terror, the betrayal, the loss, but it will never go away. Tamils Herded into Disease-ridden Camps Seek Any Escape

by Drew Warne-Smith, The Australian, October 24, 2009

Perversely, however, Kumaran believes the turmoil of past year, including the defeat of LTTE, may bring an independent Tamil state closer to reality. The Sri Lankan government's treatment of the IDPs demonstrates that the Sinhalese and Tamils cannot live peacefully side by side, he says.

"It will happen. I am confident still," Kumaran says. "Maybe they have done us a favour. They have created a bigger problem by what they have done and it will force the world to act. And they have only strengthened Tamil nationalism. They have not killed it."

WHEN Muthu Kumaran returned to Sri Lanka in February 2007, he had hoped, even expected, that his Tamil people were about to win independence.

An Australian citizen and civil engineer, he wanted to be there when a Tamil state was established, freed from majority Sinhalese rule, and he wanted to lend his expertise in water management, too.

Instead, the father of two from Sydney's west would endure the brutal reality of the Sri Lankan government's final push to wipe out the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the militant Tamil Tigers.

Kumaran was not only swept up in the renewed hostilities of a 25-year civil war, he was also detained in one of the notorious internment camps that are still home to nearly 300,000 Tamils.

He returned to Australia in the first week of August this year, having managed to buy his way out of the largest military-run camp in Sri Lanka, at Manik Farm. And with so many Tamils still detained in their homeland, and the Rudd government wrestling with how best to cope with those who have escaped and are seeking asylum in Australia, Kumaran has decided to speak out about his experience and the plight of his people.

"People need to know, the international community needs to know, what it is happening in Sri Lanka," Kumaran tells Focus.

"The US, Britain, Australia, they talk about democracy and human rights. Well, they cannot keep their eyes closed to these things."

Fearing retribution here in Australia as well as for his extended family in Sri Lanka, Kumaran - not his real name - has requested his identity not be revealed. Having first left Sri Lanka 35 years ago, Kumaran had planned on staying for an extended period when he returned in early 2007, perhaps to retire there eventually. Basing himself in the northern city Kilinochchi, the de facto Tamil capital, he initially worked alongside non-government organisations Oxfam, Solidar, Forut and ZOA on water sanitation issues, as well as helping set up livelihood projects: teaching women how to dry banana leaves and make baskets for sale and setting up street stalls. He also taught English in schools.

However, in January last year the Sri Lankan government withdrew from a ceasefire arrangement with the LTTE and the military began moving north into Tigers-held terrain in a bid to wipe them out. By December Kilinochchi was being targeted in bombing raids and Kumaran had to flee with more than 100,000 residents.

The Sri Lankan government directed Tamils to evacuate to a designated safe zone at Visuwamadu about 10km away. For the next 5 1/2 months Kumaran remained on the road, herded south through seven safe zones alongside hundreds of thousands of other banished Tamils known as internally displaced persons, or IDPs.

At each stop, an impromptu camp would be established in the belting heat, tents erected, bunkers, ground wells and toilets dug out, hospitals set up. Then a few days later the bombs would resume and this mass of humanity would move again, the numbers swelling all the time.

"The roads would be chock-a-block. Lorries, tractors, bullock carts, pick-ups, motorbikes, push-cycles, people walking, everyone carrying bags. There were young children, pregnant ladies, babies, people on stretchers, you've never seen anything like it," he says.

Kumaran also says they regularly came under fire along the way from bombs dropped by the Sri Lankan air force, rockets from naval ships, long-distance shelling and rifle rounds from the jungle bordering the roadside. He says he saw people killed and many injured. He ferried the bodies, dead and alive, to the nearest hospital or cemetery in a four-wheel drive.

"Twice my pick-up got hit, but luckily not me. I think maybe I saw a dozen people killed, maybe another 20 injured, right in front of me," he says.

By the time he left Mullivaikal in the second week of May, Kumaran was on foot, as were almost all the 300,000 Tamils, his possessions reduced to just a plastic shopping bag containing clothes and his Australian passport.

Thirty-six hours later they came to a military screening point at Vavuniya, where everyone was frisked for weapons and directed to school grounds. There, the sprawling crowd was ordered to divide into two groups: those who were associated with the LTTE and those who were not. "We were told if we were LTTE, to declare it and there would be an amnesty. But they said, 'We know you, if we find out you have lied, you will be severely punished,"' Kumaran recalls.

He joined the non-Tigers. They were then ordered on to buses and driven six hours to an area called Chettikulam, and a large swath of cleared jungle off the Vavuniya-Mannar Road. He had come to the Manik Farm internment camp. Kumaran describes the camp as a series of blocks, separated from each other by a road and strip of jungle. The facility was ringed by razor wire and guarded by armed troops.

He estimates about 2500 people were held on each block, housed in 160 tents, with 16 people to each 4mx4m tent. Each block also had a community kitchen, a medical facility and four toilets each for men and women.

Conditions were primitive at best, Kumaran says. There were no plates or utensils, so meals of dhal curry and rice were eaten off plastic bags that were reused each day. Water was limited to two 1000-litre tanks a block. Disease was everywhere.

"I volunteered to be a translator for the Sinhalese doctors at the hospital. There was a lot of typhoid, chicken pox, fever, diarrhoea, malnutrition. People had large rashes because of the lack of bathing facilities, too," Kumaran says.

"Our block, four people died while I was there, and another elderly gentleman hanged himself."

In all, he would be there for eight days. In that time he wrote to the Australian High Commissioner and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in Colombo about his detention, letters a camp official agreed to send.

But before he heard back, Kumaran says he discovered via "the bush telegraph" he could buy his freedom. He is reticent to reveal details of his escape or how much he paid, but he says he approached a local worker on his block who smuggled him out late at night two days later, hiding him in the back of a van. He presumes the camp guards knew what was happening. "The guards stopped us, but they didn't question (the driver) very much and they let us go," he says.

They were driven to another location, where they waited until the money was transferred into the required bank account.

But it would be another six weeks before he flew out of Colombo.

He lost 25kg during his ordeal, so much that airport officials were concerned he did not resemble his passport photo and it was arranged for Australian embassy officials to meet him in Bangkok to double-check his identity.

But Kumaran says there was no pleasure, or even relief, in setting foot in Sydney in early August. Instead he felt an overwhelming sense of guilt.

"As soon as I was in the air leaving Colombo, it was a bad feeling. My heart is still there," he says, tears welling in his eyes. "So many people made sacrifices, and yet still people are behind barbed wire, queuing to use the toilet and for food. They are not free. And I am here."

Perversely, however, Kumaran believes the turmoil of past year, including the defeat of LTTE, may bring an independent Tamil state closer to reality. The Sri Lankan government's treatment of the IDPs demonstrates that the Sinhalese and Tamils cannot live peacefully side by side, he says.