Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Puzzle of Greater Male Variance

Abstract

Abstract

Greater male variability on tests of mental ability would explain why males predominate not only at the highest levels in mathematics and science, but in business, politics, and nearly all aspects of life. The literature on sex differences in mental test scores was reviewed to determine whether males in fact exhibit greater variability. Two methods were used to compare sex differences in variability, ratios of total test score variances and ratios of the number of males and females scoring at or above extreme score cutoffs, or “tail ratios”. Most samples were greater than 10K. The review also included studies of physical traits such as height, weight, and blood parameters; brain volume measures; and studies of variability in four taxa, mammals, birds, insects, and butterflies. In the vast majority of total test score ratios, males were more variable than females. Males were more likely to score in the extreme right tail, indicating higher aptitude, on tests of mathematics and spatial ability in which mean sex differences favor males. On tests of writing, vocabulary, and spelling, in which mean differences favor females, males were more extreme in the left tail, indicating lower ability. Males also exhibited greater variance in physical traits, blood parameters, and brain volume measures. Similar variance differences were also found in animals. Genetic theory proposes that greater variability depends on which sex is heterogametic, that is, has two different sex chromosomes. In mammals and insects, this is the male sex, with the XY sex chromosome pair. In birds and butterflies, this is the female sex, with the WZ sex chromosome pair. It is heterogamety and not sex that determines which sex is more variable. This is because in the heterogametic sex, recessives on the single X or Z chromosome are fully expressed generating a binomial distribution with higher trait variance, while in the homogametic sex, recessive traits are averaged generating a normal distribution with lower trait variance. Females have improved their performance on mathematics tests for the gifted, with ratios falling from 13:1 favoring males in 1980 to 3:1 favoring males from 1990 onward, but the improvement has stopped. Heterogamety predicts that females, because they are homogametic, will never equal males not only in the right extreme of mathematics ability and other ability distributions but in the distribution of any trait influenced by the X chromosome.

In 2007, Psychological Science in the Public Interest published an issue devoted to sex differences in science and mathematics written by a group of contributors from fields such as neuroscience, gifted-studies, cognitive development, cognitive gender differences, and evolutionary psychology (Halpern, Benbow, Geary, Gur, Hyde, & Gernsbacher). Each author reviewed material from their specialty relating to the problem of female under-representation in mathematics- and science-based fields in academia, research, and industry. The group concluded that observed sex differences result from both genetic influences and sociocultural differences in the treatment of males and females, most certainly an anodyne conclusion of the kind expected from a committee of disparate experts.

The 2007 article was in part a response to the controversy following statements made two years earlier by then Harvard University president Lawrence Summers to the effect that there were fewer women in academia and industry because fewer women score at the highest levels on tests of aptitude predicting success in mathematics and the hard sciences. This was tantamount to saying that, at the highest ability levels, women are inferior to men. Summers’ statement about women was a major factor in his 2006 resignation as Harvard’s president. Regardless of campus politics, which also played a large role in his departure, the question remains, why do men dominate at the highest levels of mathematics, science, business, and industry?

Last year, the issue of sex differences arose again, this time in the citadels of technology, in particular the Silicon Valley offices of Google and the claim by one software engineer, James Damore (2017), that, among other things, ���differences in distributions of traits between men and women may in part explain why we don't have 50% representation of women in tech and leadership.” This was Summers’ explanation exactly, and for offering it, Damore experienced a fate similar to Summers’: He was fired.

The topic of cognitive gender differences being much too broad for any one article, this paper considers only the issue of greater male variance on mental ability tests. This review updates the 2007 Public Interest article now that more than 10 years have passed and considers new findings, which include much larger samples of test data than were then available, and recent research published by geneticists and behavior geneticists shedding new light on this controversy.

The approach I’ve taken in this review was dictated by the issue under study, the variance of mental ability as reported in a wide range of aptitude and achievement tests of children and adolescents. While it might seem preferable to perform a meta analysis of many study results, the variance statistic does not lend itself to this approach. Pooling effect sizes from different samples can give a better estimate of true population mean difference than individual studies. But it is difficult to know what group is represented in the result when a meta-analysis is performed on heterogeneous variances. Studies of variance should be based on large nationally representative samples, not heterogeneous studies of selected groups, some based on selected samples, thrown together and christened a meta-analysis leaving the reader with the question, “What is the population the parameter of which is being described?” For a brief yet astute discussion of the perils of using meta-analysis to study sex differences in variance, see Hedges and Nowell (1995) Pages 41-42.

If meta-analysis is inappropriate, what other approach can one take? In the studies reviewed here, a wide variety of tests were given to children ranging in age from early childhood through late adolescence. I have chosen to review the 17 studies individually, presenting reported sex differences in means, variances, and tail ratios in separate tables for each study. After reviewing each study, I discuss its merits, for example, Did the study assess aptitude or achievement? Did subject age affect the results? What patterns exist across tests of domains such as verbal, mathematical, spatial, and science aptitude; change in variances over time, etc?

None of the data in the studies reviewed here were generated by the researchers for the purpose of comparing male and female variance, nor could it be, the sample sizes required are too large. In every instance, tests were given to meet an institutional requirement such as college entrance or by a government agency assessing student progress or teacher/school effectiveness. The sample sizes were large, some having tested or screened millions of students randomly sampled from large countries such as the U.S. and UK, and in one case, the PISA test of 276,165 15-year-old students from 41 developed and developing nations. The results were data sets that largely spoke for themselves with little data manipulation needed. In most cases, I have reproduced the key tables from each study to enable inspection of the supporting evidence for the issue under review.

Requirements to Show Sex Differences in Variability

Sources of Differences in the Right Tail of Distributions

Of interest here is the difference in the frequency of extreme scores in the tails of test-score distributions. More males will be found in the extreme right of a distribution if males have a higher mean and both sexes have the same variance, or if both sexes have the same mean but males have a greater variance, or if males have both a higher mean and greater variance. No studies with the exception of Nowell and Hedges (1998) using a method developed by Lewis and Willingham (1995) attempt to partition the relative frequencies of extreme scores into components due to mean differences and variance differences.

Measures of Sex Differences

Virtually all of the reviewed studies of sex differences report the mean sex difference and the total test score variance ratio or VR. They also report “tail ratios,” a proportion comparing the number of males and females scoring above a given cut off in the extremes of distributions.

Means are universally compared using Cohen’s d (1988), the mean difference standardized by the pooled within-groups standard deviation:

(MeanM – MeanF)/√(VarM + VarF)

Cohen’s (1988) criteria for assessing the importance of d are .20, small; .50, medium; and .80, large. In most of the studies reviewed below, d was calculated as male mean – female mean. In those few studies were it was calculated female mean – male mean, I reversed the sign and so noted in the footnotes to the tables where I did this.

The standard deviation is the most commonly used measure of test-score dispersion, but its square, the variance, is a better measure of variability because its ratio can be used to compare the variability of different groups. To do this for males and females, the simple ratio of male over female variance is computed:

VarM/VarF.

A ratio of 1.0 indicates equal male and female variances. Ratios larger (smaller) than 1.0 indicate greater (lesser) male variance. Feingold (1992) suggested that a difference of 10 percent in the variance, or a variance ratio of 1.10, is the minimal required for the difference to have substantive importance. In all of the studies, the variance ratios were calculated as male variance/female variance.

Tail ratios are a simple means of comparing performance at the extremes of test score distributions. The counts of males and females within the 10%, 5%, and .01% cutoffs provides the ratio of males and females performing at or above that level:

CountM/CountF.

Much like VR, a tail ratio of 1.0 indicates that the number of males and females scoring above a given cut off is equal. Ratios larger (smaller) than 1.0 indicate more (fewer) males scored at or above the cut off. An increase in tail ratios with successively higher cut offs indicates that a greater disproportion of males is scoring at higher levels and thus possesses to a greater degree whatever latent trait the test measures. In all of the studies, the count ratios were calculated as male variance/female variance.

Some studies look only at the right tail of the distribution. Samples selected for high scorers will reduce the variance by truncating the left side of the distribution. For these studies, is it not useful to estimate the population variance but rather to compare the counts of males and females scoring at or above a given cut off score, that is, tail ratios. Lewis and Willingham (1995) found that the mean sex difference in restricted samples was correlated with the variance difference.

Volunteers are known to differ from the general population. Children who volunteer for enrichment programs, or whose parents do the volunteering, are likely to be more motivated and different from a nation-wide sample of non-volunteer same-age children in intelligence, motivation, SES, race-ethnicity, etc.

Factors Affecting Variance Differences

Age. Haworth, Wright, Luciano, Martin, de Geus, van Beijsterveldt, & Plomin (2014). found that the heritability of general intelligence increases with age, from .41 to .55 to .66 at ages 9, 11, and 17 respectively, in a study that pooled 10,689 MZ and DZ twin pairs from six studies done in four countries. Others have suggested that heritability is as high as .80 in late adulthood (Johnson, Carothers, & Deary, 2009; Plomin & Deary, 2015). At the very least, tests should be of young adults although there is no large-scale testing of persons older than those taking graduate school admissions tests like the GRE.

Range Restriction. Because we are interested in the relative number of males and females scoring in the tails of the test distribution, there should be no ceiling or floor effects. An ideal test would have few or no zero or perfect scores to assure that the difficulty of the test matched the ability of the test takers.

Unselected Samples. Ideally, samples should be unselected to ensure that the full distribution of ability within a population is tested. This can be achieved with a procedure such as national probability sampling, which is the best means to obtain a truly representative sample of the nation as a whole. There are large samples of selected populations such as the SAT and GRE, tests used to screen students for college and graduate school. But these samples are neither random nor representative despite samples numbering in the millions.

Aptitude Versus Achievement Tests. Aptitude tests measure student ability and achievement tests measure student learning and school effectiveness. It is better to study tests of aptitude rather than achievement if we are studying ability although it is impossible to study any ability divorced from previous learning experience. Unfortunately, there are few large-scale studies of “culture-free” tests of intelligence, such as the Raven Progressive Matrices. Societies economically developed enough to do large-scale testing also have compulsory schooling usually through the American equivalent of high school. Large-scale testing is done with school children and adolescents to monitor their progress and to screen for college and graduate school admissions. An example of using large-scale testing over a range of ages is the No Child Left Behind program, which required regular testing of elementary and high school children to determine whether they were achieving specific learning goals and whether teachers were performing up to standard (Zelizer, 2015). Some schools whose students failed to progress adequately were closed. The diversion of classroom time and school resources away from instruction to prepare students for these achievement tests has been a source of parental complaints (Strauss, 2015). To the extent that test preparation becomes “teaching to the test,” sex differences in the means and variances will be reduced.

Genetic theory

This paper will show that the sex difference in variance is due to the difference in their chromosome allotment, namely the difference in the sex chromosomes, XX for females and XY for males. There is no difference between males and females with regard to the 22 pairs of somatic chromosomes, the autosomes. Both males and females have the same chromosomes and the same coding regions and alleles on all 22 pairs of autosomes. The random process by which they are assigned those alleles is the same for both sexes. But with the sex chromosomes, X and Y, the genetic allotment is different. Because the Y chromosome that men receive is vestigial, it leaves the X chromosome unpaired so that not only are dominant alleles fully expressed, recessive alleles are also fully expressed. In females, the pairing of two X-chromosomes means that recessive traits are expressed only if there are recessive alleles on both X chromosomes, which reduces the probability that the recessive trait is expressed to the square of the probability for males, one source of lower female variability.

Johnson et al. (2009) demonstrated how this works in a simple model of a single gene with two alleles on the male single X chromosome,

A and a,

that will have the maximum population variance of

0.5 x 0.5 = 0.25

when the allele frequencies are equal. For both the dominant and recessive alleles, their probability of expression is equal to their proportion in the genome.

Matters are different for females, who have three genotypes arising from the same two alleles because the two alleles, A and a, are on one of two different chromosomes, XX,

AA = 0.25, Aa = 0.50, and aa = 0.25.

In a perfect world, this would lead to reduced variance in females because the phenotypic expression of AA and Aa are the same when there is complete dominance and thus a lower population variance of

(0.25 + 0.50) x (1.0 - 0.75)

0.75 x 0.25 = 0.188.

But the fact that females have two X chromosomes while males have one complicates matters. This is an imbalance that nature corrects by silencing or “inactivating” one of the two female X chromosomes. Which X chromosome is silenced is randomly determined early in gestation when the embryo is between 8 and 16 cells (Craig et al., 2009). Half of these cells will have chromosome X1 with allele A and half will have chromosome X2 with allele a. This equal splitting of the two X chromosomes and their different alleles will lead to phenotypic expression that is the average of allele A and a. Because half the females have the heterozygous genotype Aa, and one-quarter each have the homozygous AA and aa genotypes, their distribution is more approximately normal and has a smaller variance than the binomial distribution of A and a in males. In short, this is the source of greater male variance and is discussed in greater detail below.

Published Studies

The following studies present in some detail what I think is the most comprehensive review extant of the literature bearing on the issue of male and female variance in mental ability testing. The studies reviewed unmistakably make the case that 1) males are more variable with regard to virtually all tests of mathematical, spatial, and science aptitude and achievement at both the high and low ends of the respective test score distributions and 2) many tests of verbal aptitude and achievement especially at the low end of the test score distributions.

Benbow and Stanley (1980, 1983)

The issue of differential variance was given it’s current prominence by Benbow and Stanley who reported in two papers (1980 and 1983) on sex differences in mathematics based on large samples of mostly 7th grade children who were given both the verbal and mathematics sections of the Scholastic Aptitude Test as part of the Study of Mathematically Precious Youth (SMPY).

The SAT-Mathematics test (SAT-M) is normally taken by college-bound high school seniors, who at age 17 or 18, are 5 to 6 years older than the SMPY 7th graders, all of whom were age 12 except for a small number of 13 year olds in the early years of the study. Few of the SMPY children had taken algebra or had any formal training in the skills needed for the SAT-M. Benbow and Stanley (1980) gave the SAT-M not to test mathematical aptitude, but because the test was so far above the skill level of 7th graders that the SAT-M would be a test of their “numerical judgment, relational thinking, and logical reasoning.” Spearman (1904) would recognize the ability Benbow and Stanley were testing as general intelligence or g.

The 1980 report was based on the scores of 9,927 students who were recruited from the greater Baltimore region between 1972 and 1979 after scoring in the top 2 to 5 percent on a mathematics screening test. Tables 1 and 2 show the results for both the verbal and mathematics scores. Removing the 8th grade scores for December 1976 because of the small N, the mean d value of -.03 for the verbal scores shows that males and females were about equal in verbal reasoning and the mean variance ratio of 1.04 also suggests parity in variability. But the mean d value of .50 and the mean variance ratio of 1.58 for mathematics scores shows that males score a half standard deviation higher and were nearly 60 percent more variable than the females. The extreme mathematics scores were even more disparate, 16.6% of the males scoring above 600 but only 2.1% of the females.

In 1983, Benbow and Stanley reported results on the SAT-M from nearly 40,000 students in the mid-Atlantic region and another large group from a nationwide talent search within and beyond the Johns Hopkin’s talent search area. All students were under age 13. The results were similar to those from the earlier study. No difference was found in the SAT-Verbal, with the male and female means 367 and 365 respectively (Standard deviations not reported). But there was a 30-point mean difference on the SAT-Mathematics, with the male and female means 416 and 386 respectively. The variance ratio was 1.38, roughly the same as in 1980 and showing again that males are more variable than females. More importantly as shown in Table 3, the number of boys scoring above 700 on the SAT-M over both national search samples, was 13 times the number of girls (260:20), despite equal numbers of boys and girls taking the screening test.

Comment. Benbow and Stanley’s findings gave enormous impetus to research on sex differences in cognitive ability generally and to sex differences in variability specifically.

The extreme 13 to 1 ratio has become ingrained in the literature on sex differences in variability even though it has been out of date since 1990, the ratio now being 2.8:1, or in round numbers 3:1. Use of the SAT allowed Benbow and Stanley to avoid ceiling effects: Few students scored above 700, and in many years, no one scored a perfect 800. Their samples were young and highly selected, making it possible to generalize only to the very brightest students rather than to the population of seventh graders as a whole. The students were volunteers, a special group that probably differs in many ways from students in general although it is unlikely that these factors substantially affected the differential pattern of scoring. Comparing means and total score variances between two groups all of whom are in the right tail of the score distribution is questionable.

Benbow and Stanley (1980, 1983) were among the earliest to note that the traditional arguments made to explain the lower numbers of extremely able females in mathematics, such as lack of opportunity to study math and social attitudes discouraging females from pursuing careers in math and science, would create mean differences between the sexes not variance differences. Benbow and Stanley also noted that through 11th grade, boys and girls have taken the same math courses, obtain about the same grades, and rate similarly their liking for mathematics and their perception of mathematics as important. Summarizing their assessment of theories explaining male superiority at the highest score levels in their 1980 report, Benbow and Stanley stated that “boy-versus-girl socialization” as the only acceptable explanation of the sex difference is “premature,” and in 1983, said that the reasons boys “dominate the highest ranges of mathematical reasoning ability were unclear.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

More Ideas on Population and Immigration

If there is one thing that would bring population back into the national debate over immigration it is challenging the media’s near refusal to connect the two. Only rarely does one see the implications for population mentioned in articles about immigration. This is also true of environmental reporting in general as was first discussed by T. Michael Maher more than four decades ago. Talk of population is forbidden in the media unless it’s someone else’s population, like China’s or India’s. Paul Ehrlich’s now classic 1968 book, The Population Bomb, sold 2 million copies and changed not only popular attitudes about population as an environmental issue, but made population a key issue in the media as well. In 1969, Richard Nixon devoted an Oval Office speech to population and appointed the Rockefeller Commission on Population Growth. We need to rekindle the national consensus on reducing population growth created by Ehrlich’s book and apply it to immigration.

One reason The Population Bomb created such a stir is that it came at a time of widespread public questioning of entrenched policies and of anti-establishment skepticism created by the Vietnam war. The social and political movements of the 60s led to the first Earth Day and the modern environmental movement. For reasons discussed in Roy and Leon’s “retreat from stabilization” article, population is no longer the signal environmental issue it was 50 years ago and is now taboo among many environmental organizations. Despite this, the key to reviving population as a domestic issue is access to the media. In an earlier message, I said that we needed something like the Worldwatch Institute. In fact, there already exists two similar institutions for immigration, the Center for Immigration Studies, and, of course, NumbersUSA. The closest existing organization for population is Progressives for Immigration Reform (PFIR). PFIR must raise its profile.

The following is an example of how that might be done:

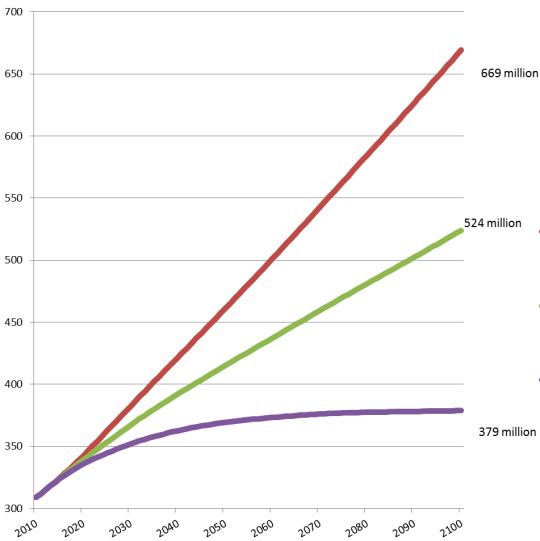

Most Americans have no idea how much U.S. population will grow under different immigration scenarios. But the graph of population drivers pasted into Table 1 from the Census Bureau’s web site and the projections of future population growth pasted into Table 2 from the PFIR EIS report give a glimpse of an overpopulated future no one wants. There is a YouTube immigration channel in Canada. Can NUSA set up its own YouTube channel that shows the inevitable future mass immigration will impose? Such a “channel” would be the most cost effective way of getting the message out. NUSA could also use the channel to better publicize its work on sprawl and other issues. The audience is potentially much larger than on-line YouTube views of current material, which are short and may be attracting only the converted, that is, immigration activists who may be bumping up the view number with repeated viewing.

Table 1

Contributions of Fertility and Migration to Future U.S. Population

https://census.gov/library/visualizations/2018/comm/international-migration.html

Table 2

Estimated U.S. Population Based on Three Immigration Scenarios: No Change (green), Reduction (purple), and Expansion (red)

file:///C:/data/immigration/LeonPFIRFina-immigrationEIS2016MayComplete2016.pdf

This Op-Ed by Hahrie Han appeared in the New York Times after the Las Vegas shooting last October. The author is a Political Science Professor at UC, Santa Barbara, who has also written a book, ”How Organizations Develop Activists: Civic Associations and Leadership in the 21st Century,” available at Amazon. Chapter 1 is online here.

In explaining why in the debate about gun control at the federal level, gun rights nearly always win over gun control, she notes that, “Gun-control groups focus on persuasion, while gun-rights groups focus on identity.” People join the NRA because gun ownership is a way of life. They find the passage of gun control measures personally threatening and like nothing better than defending gun rights. The NRA might be the original grass roots lobbying group. Much like NUSA, the NRA mails warnings to the rank and file of pending legislation on gun rights and provides post cards each member can mail to their elected officials. This has made the NRA a feared lobbying force on Capital Hill with a proven record of unseating congressmen who failed to toe the NRA’s party line. Han notes that 80,000 NRA members from all over the country attended its annual meeting in 2017. How many would attend a similar meeting held by NUSA? Han also notes that she joined a gun-control group and sent emails and made calls until, feeling like “a prop” in someone else’s game, she quit. Over a number of years starting in 1997, I sent hundreds of faxes, and made thousands of calls, as many as 50 in a day. But I also quit recently because there was little satisfaction in being one of the “lone wolves” Han describes in her Chapter 1, although other matters were also more pressing.

It might be worthwhile for NUSA to hold a national or regional meeting, just to see what emerges from it. A meeting would bring people together and build friendships around immigration reform, and might, as Han describes in her Chapter 1, engender a greater sense of commitment among activists. Another possibility is to create “organizers” in Han’s sense by making one NUSA member a “leader” in an area who contacts others to make sure they send faxes in a timely fashion. The leader could hold meetings to generate a sense of shared mission. We need to remind people that if mass immigration isn’t stopped, there will be no place to take a vacation from overpopulation, including their favorite Montana fishing spot. My guess is that this would be too expensive and would require organizational structure beyond NUSA’s resources. Despite this, the thought experiment might still be worthwhile.

Here is what Han says about which groups are effective and which not:

“When I studied groups that were most effective at building a grass-roots base, I found that the key factor to success was the nature of the relationships they created. The most effective groups used relationships as a vehicle for bringing people off the sidelines of public life and teaching them to speak truth to power. You can’t convince someone to rethink who they are or what responsibility they want to take for their community through a mailer.”

“Building a movement will require organizations to invest in the leadership of ordinary people by equipping them with the motivations, skills and autonomy they need to act. Most organizations never give people that opportunityIn her Chapter 1, Han mentions on-line video conferencing as a means of organizing. You might want to keep your eyes peeled for this as a way of having virtual meetings that might serve as an cheap, convenient organizing tool.

In her Chapter 1, Han mentions on-line video conferencing as a means of organizing. You might want to keep your eyes peeled for this as a way of having virtual meetings that might serve as an cheap, convenient organizing tool.

Start an immigration “truth squad.” Call out James Fallows whose cheery self-righteous comments about African immigrants in Nebraska meat processing plants left out any mention of how jobs that were once well-paying and unionized are now reminiscent of Upton Sinclair’s Jungle, which was written in an era of mass immigration much like ours. I may be cherry picking this one comment, which I mentioned in an earlier letter, but someone needs to correct writers who believe that mass immigration has no consequences. The Times columnists, David Brooks and Brett Stephens, are singularly oblivious in this regard.

Another whooper was by John Kerry, who commented before he ran for President that, “America is underpopulated.” And this by the co-author of This Moment on Earth: Today’s New Environmentalists and Their Vision for the Future. The book is about the activists Kerry met during his 2004 presidential campaign. Apparently, it never occurred to Kerry that blowing up this country’s population would undo all the efforts of his “new environmentalists.” Someone needs to clarify this for him.

A third example is from Senator Lindsey Graham, who recently said, “We can’t reduce immigration because we need economic growth.” If continual population growth is required to have a “good” economy, then population will have to grow indefinitely. This is one of the fundamental flaws in the triumvirate globalist policy espoused by Republicans like Paul Ryan and free traders like the Koch brothers: Tax cuts, free trade in goods and services, and free flow of labor. This juggernaut is what dominates thinking in the U.S. Senate and makes NUSA’s job impossible. Note that immigration was not slowed at all during the Great Recession, even with 10 percent unemployment.

One particular group that might be a source of recruits for the immigration wars is local growth controllers. After looking at web sites and exchanging emails, I’ve learned that the leadership of groups like American Farmland Trust and Sprawl City don’t want to be seen as blaming immigrants for sprawl. But some rank-and-file members might feel differently.

I wouldn’t make too much of the most recent Pew poll on attitudes toward immigration. Even though it was largely done before the “zero tolerance” policy made headlines, which might have created a “social desirability” effect (telling the interviewer what the respondent thinks the interview wants to hear), the poll shows public attitudes on immigration softening. But the real story is how ignorant the public remains about basic aspects of immigration. Some 35 percent of respondents believe most immigrants are here illegally. This means that a third of the public does not understand the distinction between legal and illegal immigration, the most basic distinction of all.

In his book, Huddled Masses Muddled Laws, Kenneth Lee describes how in 1996, pro-immigration lawmakers made use of this confusion to essentially hoodwink the public into settling for a weak bill on illegal immigration while leaving legal immigration untouched. The book is relatively short and should be required reading for all population activists. Our job is to educate the public on immigration basics (that YouTube channel?) and how the status quo is unsustainable.

I hope there is at least one good idea here. It’s ironic that one immigrant “sob story” gets more space in the New York Times than even a mention of projected population growth and all it entails.

Sincerely,

Fred W. Johnson

0 notes

Text

Reconsidered response to Rob Harding’s Post

I’ve reconsidered after sending a first dispirited email that said it was hopeless attempting to counter the political correctness of environmental group leaders. Here are some ideas:

The best strategy to counter political correctness is to develop an alternative narrative and deny the ideologists political space. There is an implicit ethnocentrism in statements like this one from one of your environmental group “leaders” who refers to U.S. citizens as “…those lucky few of us already on the inside of the right borders.” The arrogance of this statement is breathtaking. It says that the U.S. is the only country on the planet worth living in and one cannot have a good life outside its borders. This is not unlike Donald Trump’s “s---hole” statement about African countries. In fact, most people are proud of their country of origin, just like Americans are of theirs. Living in Berkeley CA, I’ve known many immigrants and none trashed their country of origin like this.

In your interviews, did you ask any of these leaders their number? That is, their estimate of the largest possible sustainable U.S. population. One leader said, “We do not oppose migration of people into the United States and do not support coercive population control measures of any kind. Immigration and the pursuit of better circumstances are basic human rights, and U.S. immigration policies should always be rooted in human dignity.” If this is what they believe, these leaders are not for population stabilization at all. I get the impression that they are for unlimited U.S. population growth so long as all the growth is from the Third World poor. That’s a nice sentiment, but totally impractical and has nothing to do with stabilizing U.S. population. If we are to import huge numbers of the world’s poor and maintain a stable population, this statement amounts to telling U.S. citizens that they should stop having children in order to make room for millions of the foreign-born poor.

If these groups are not population organizations, what is the purpose of their group, population substitution? Out with U.S. citizens, in with the world’s poor? Has even one of these ivory tower population “leaders” tried out such ideas on the American public? Have they asked the average American if they agree that they should, in effect, have their tubes tied to make more room for the foreign-born poor? Have they polled Trump voters? As the Democrats are learning at the presidential level, a new policy has to pass the “Joe Sixpack test.” If it doesn’t, it might play well with ideological college kids, but it won’t win elections.

James Fallows and his wife are on tour selling their new book, “Our Towns,” telling Commonwealth Club members and NPR listeners that Somali immigrants and refugees working in Nebraska’s slaughterhouses are a wonderful example of immigration working for all concerned. Did Fallows take a look inside those slaughterhouses to see what’s really going on? Those jobs used to be in the industrial north, in cities like Chicago, and paid a good union wage with overtime and benefits. Unfortunately for these Somalis, their American Dream is the globalized American sweatshop: dangerous working conditions, no overtime or medical benefits, long shifts, and rock-bottom wages to supply China, the ownership’s home country, with cheap, imported American pork. The existence of a new American slavery based on cheap immigrant labor needs to be publicized.

We need a research center like Lester Brown’s Worldwatch Institute. We could document the ongoing destruction of wildlands, wetlands, open space, and farmland (both prime and otherwise), and water in the west, just like Brown did in the “Vital Signs” books that had for each topic, a graph and text on facing pages clearly showing and discussing trends.

Water in the western U.S. is always a critical problem, made worse by climate change. Development and dwindling snow packs are at a critical juncture. Lake Mead behind Hoover dam is nearing deadpool, when the lake level falls below the intakes; Lake Powell behind Glenn Canyon dam has been near deadpool for years. Limiting further development in the American Southwest is already being talked about by writers like Kathleen Parker, Char Miller, and many others including immigration cheerleader Jerry Brown, who was governor of California during the recent multi-year drought. Nowhere in the U.S. are water resources being pushed to the limit as in the Southwest. A huge proportion of the Southwest’s population growth is from immigration, legal and otherwise. Groups like NUSA need to be at the table when steps are taken to allocate the Southwest’s most precious and scarce resource, water.

This animation of San Jose’s growth by Joel Clark, shows how San Jose expanded during the 50s and 60s under the go-go city manager, A.P. “Dutch” Hamann, the main force behind the conversion of the Santa Clara Valley, once known as the Valley of Heart’s Delight because of its fruit orchards, into Silicon Valley’s bedroom community, a tangle of freeways, houses, and shopping malls. Videos of this sort could be created for every city in the country. Something similar to the San Jose story may be in store for the Puget Sound lowlands stretching from Seattle, WA to Vancouver, BC, now being touted as a “Cascadia innovation corridor.” To cash in, developers use targeted campaign contributions to pack county supervisory boards with Republican toadies; ditto for house members and senators. Farmers don’t have a chance; they’re easily bought out or taxed off their land; high tech has greater value added. If that corridor can be built, what is to prevent a similar fate for the entire Willamette Valley in Oregon, and the what remains of the Central Valley in California? This would be a disaster for the entire country, but it’s well on its way to happening.

Maps like Clark’s can be made that show the INCREASE of: urbanization, sprawl, roadways, pipelines, and power lines overlayed to show how much of the U.S. has been “developed;” nearly all of it. By the same token, maps can be made that show the DECREASE of: farmland (prime and otherwise), open space, wildlife habitat, free flowing rivers (if any are left), and wilderness. A three-dimensional mesh plot with density contours, which can be programmed in R, would show how development has already swallowed most of the country.

Leon Kolankiewicz, Anne Manetas, Roy and possibly others have written long detailed reports on what population growth and sprawl have done to Florida, California, and the entire U.S. Some of these are outdated but are still relevant as records of what has been done irreversibly, and begs the question, “When will this stop?” These studies may be on the web right now, but should be given much greater publicity along with computer graphics to make their point more visually. In the late 1990s, NUSA gave me copies of several sprawl studies, but in my case it was preaching to the choir. These studies should be updated and broadcast more widely.

To explain the origin of the terms “chain immigration” and “diversity lottery,” educate voters about the Jordan’s commission’s 1996 report. Papers like the New York Times editorialized against these proposals, but never made clear where these terms came from or who first proposed them. It would have been harder for the mainstream press to toss aside these measures if the public knew that the rationale for ending chain migration and the lottery came from Barbara Jordan more than 20 years ago. The NUSA chain migration TV ad is great, but there needs to be more public education to provide context.

Studies have shown that as societies increase in size, participation in civic life declines and people feel excluded from political life. Only nations like Ireland and the Scandinavian countries are still small enough so that there is greater participation and a sense of civic engagement. The larger the population, the less people feel that voting matters: “Why bother to vote, I’m only one person?” How would these “leaders” answer this question?

We should offer an alternative vision for America that builds around E. O. Wilson’s idea of devoting half the planet to wildlife habitat. Note that both Lester Brown and Wilson, were lobbied by the Sierra Club board of directors during the 1998 vote on immigration. Both turned down the board and voted against its proposal and in favor of reducing immigration.

All of this requires money. To do just the mapping studies would require probably three people, a coder, a writer and a data manager. I have few ideas on funding, except that the Colcom Foundation is one possible source. A second possibility is crowd sourcing. Where is the George Soros for population?

Political correctness will win only if we allow it to. Most Americans are pragmatic, reject ideologies, and agree that population is a problem here and around the world. Knowing that, we can define this issue in our terms and not those of the left-wing ideologues.

Fred W. Johnson

0 notes

Text

The two posts above, “Reconsidered” and “More ideas,” were written in response to this email sent to me by Rob Harding at NumbersUSA. Sustainabiilty Watch July 8, 2018

For 9 months, I've had scores of conversations with environmental leaders and thinkers about immigration's impact on the U.S. population and environment.

Here is what I heard.

"I hope the Trump administration is successful at reducing future immigration flows because such incessant population growth is inhibiting our ability to conserve other species' habitats. But I won't share this view publicly in today's polarized political climate."-- a university editor of an environmental newsletter

I'm all in on population control in the US, have a bookshelf full of [population-environment] books here at home, and I've never lost sight of the firm connection between population growth and habitat loss and global warming. But it has been increasingly challenging to come out for immigration reductions as the number of right-wing racist crazies has increased." -- a leader in a national conservation group

WHY AREN'T ENVIRONMENTAL LEADERS SPEAKING FOR U.S. STABILIZATION?

As we approach the 50th anniversary of Earth Day (in 2020), I've wanted to know why I'm not seeing much leadership from environmental groups, leaders and writers in supporting limits to immigration that would allow the U.S. population to stabilize in this century.

After all, the founder of Earth Day - Sen. Gaylord Nelson - (D-Wis.) was clear about the responsibility of environmentalists to address these issues.

"The bigger the population gets, the more serious the problems become... We have to address the population issue. The United Nations, with the U.S. supporting it, took the position in Cairo in 1994 that every country was responsible for stabilizing its own population. It can be done. But in this country, it's phony to say 'I'm for the environment but not for limiting immigration.'" -- Gaylord Nelson, 2001 interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

I've spent these last nine months in conversations with fellow environmentalists across several disciplines who understand our current state of global ecological overshoot and its axiomatic connection to the size and growth of human populations.

While most of the people I spoke with recognize immigration's role in driving continued U.S. population growth and acknowledge that such growth undermines U.S. ecological sustainability, many of the same people refuse to publicly support limiting immigration as a necessary component of any plan to achieve U.S. population stabilization.

The quotes below are representative of most of the answers I got over these months of searching.

The people with whom I spoke knew I was with NumbersUSA. But I do not use their names or identify their organizations because I wish to shine a light on the overall thinking behind the overwhelming silence of so many, rather than criticize specific individuals (and their organizations) who were kind enough to talk candidly with me.

"We are practically on the same page except for migration. I believe that, in the short term, in order to avoid a major humanitarian calamity, the global North must be more receptive to migration from the global South, albeit with proper filters for troublemakers." -- an editor of an environmental journal

"On the immigration issue, if climate scientistsare anywhere close to correct, the world may live to see huge movements of people this century. Compassion is the only appropriate response to such potential massive suffering, not laws to shut people out or pretend it is someone else's problem. I believe it is of paramount importance that we, environmentalists, steer fully clear of past mistakes of population controls and, relatedly, get a big chunk of the social justice contingent on our side. We should try to avoid recycling any past acrimonies and misunderstandings."-- a Southeast university author

". . . unsustainable human population numbers, overconsumption, and damaging resource extraction and production techniques are critical factors in the planetary extinction crisis, climate change and ocean acidification. However, because population, consumption and extraction/production are global issues that transcend national borders, we do not view national immigration policy as the appropriate target for addressing these issues.

"We do not oppose migration of people into the United States and do not support coercive population control measures of any kind. Immigration and the pursuit of better circumstances are basic human rights, and U.S. immigration policies should always be rooted in human dignity. While there is room for debate over the best methods to manage immigration, we do not view it as the way to address population growth, over-consumption, urban sprawl, unsustainable growth, and the effects they have on wildlife and the wild places they need to survive and thrive." -- a leader in a national ecology group

"[T]he idea that we should limit immigrationinto the US in order to combat this problem that we are contributing so extensively to worries me quite a bit. It feels like shutting the doors to protect our privilege, after we've done so much to make the world unlivable for some of the people trying to get in.

"[O]ne of the reasons we need to reduce fertility so aggressively in the developed (overdeveloped) world is so that we have room to do what justice demands, which is to let in refugees and those looking to improve their lot by taking advantage of our sunk carbon costs (infrastructure). This makes me unpopular with important allies, I know, as many overpopulation advocates are worried about immigration into high-consuming countries; but I think we get to work to correct one injustice through another injustice (one which, it so happens, protects those lucky few of us already on the inside of the right borders)." -- a Northeast university author

Jul. 5

th

, 2018

SUSTAINABILITY WATCH

For 9 months, I've had scores of conversations with environmental leaders and thinkers about immigration's impact on the U.S. population and environment.

Here is what I heard.

"I hope the Trump administration is successful at reducing future immigration flows because such incessant population growth is inhibiting our ability to conserve other species' habitats. But I won't share this view publicly in today's polarized political climate."-- a university editor of an environmental newsletter

WHY AREN'T ENVIRONMENTAL LEADERS SPEAKING FOR U.S. STABILIZATION? MORE QUOTES

I'm all in on population control in the US, have a bookshelf full of [population-environment] books here at home, and I've never lost sight of the firm connection between population growth and habitat loss and global warming. But it has been increasingly challenging to come out for immigration reductions as the number of right-wing racist crazies has increased." -- a leader in a national conservation group

As we approach the 50th anniversary of Earth Day (in 2020), I've wanted to know why I'm not seeing much leadership from environmental groups, leaders and writers in supporting limits to immigration that would allow the U.S. population to stabilize in this century.

After all, the founder of Earth Day - Sen. Gaylord Nelson - (D-Wis.) was clear about the responsibility of environmentalists to address these issues.

"The bigger the population gets, the more serious the problems become... We have to address the population issue. The United Nations, with the U.S. supporting it, took the position in Cairo in 1994 that every country was responsible for stabilizing its own population. It can be done. But in this country, it's phony to say 'I'm for the environment but not for limiting immigration.'" -- Gaylord Nelson, 2001 interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

I've spent these last nine months in conversations with fellow environmentalists across several disciplines who understand our current state of global ecological overshoot and its axiomatic connection to the size and growth of human populations.

While most of the people I spoke with recognize immigration's role in driving continued U.S. population growth and acknowledge that such growth undermines U.S. ecological sustainability, many of the same people refuse to publicly support limiting immigration as a necessary component of any plan to achieve U.S. population stabilization.

The quotes below are representative of most of the answers I got over these months of searching.

The people with whom I spoke knew I was with NumbersUSA. But I do not use their names or identify their organizations because I wish to shine a light on the overall thinking behind the overwhelming silence of so many, rather than criticize specific individuals (and their organizations) who were kind enough to talk candidly with me.

"We are practically on the same page except for migration. I believe that, in the short term, in order to avoid a major humanitarian calamity, the global North must be more receptive to migration from the global South, albeit with proper filters for troublemakers." -- an editor of an environmental journal

"On the immigration issue, if climate scientistsare anywhere close to correct, the world may live to see huge movements of people this century. Compassion is the only appropriate response to such potential massive suffering, not laws to shut people out or pretend it is someone else's problem. I believe it is of paramount importance that we, environmentalists, steer fully clear of past mistakes of population controls and, relatedly, get a big chunk of the social justice contingent on our side. We should try to avoid recycling any past acrimonies and misunderstandings."-- a Southeast university author

". . . unsustainable human population numbers, overconsumption, and damaging resource extraction and production techniques are critical factors in the planetary extinction crisis, climate change and ocean acidification. However, because population, consumption and extraction/production are global issues that transcend national borders, we do not view national immigration policy as the appropriate target for addressing these issues. "We do not oppose migration of people into the United States and do not support coercive population control measures of any kind. Immigration and the pursuit of better circumstances are basic human rights, and U.S. immigration policies should always be rooted in human dignity. While there is room for debate over the best methods to manage immigration, we do not view it as the way to address population growth, over-consumption, urban sprawl, unsustainable growth, and the effects they have on wildlife and the wild places they need to survive and thrive." -- a leader in a national ecology group

"[T]he idea that we should limit immigrationinto the US in order to combat this problem that we are contributing so extensively to worries me quite a bit. It feels like shutting the doors to protect our privilege, after we've done so much to make the world unlivable for some of the people trying to get in. "[O]ne of the reasons we need to reduce fertility so aggressively in the developed (overdeveloped) world is so that we have room to do what justice demands, which is to let in refugees and those looking to improve their lot by taking advantage of our sunk carbon costs (infrastructure). This makes me unpopular with important allies, I know, as many overpopulation advocates are worried about immigration into high-consuming countries; but I think we get to work to correct one injustice through another injustice (one which, it so happens, protects those lucky few of us already on the inside of the right borders)." -- a Northeast university author

More Quotes

"Is it in [anyone's] interest to have a total societal collapse? No. If we want to prevent that we need to make some hard choices. Reduced immigration is important, but so is having fewer children." -- a leader in an environmental think tank

"The overwhelming view in international organizations -- and that means most environmental groups as well as the UN (including UNEP), World Bank, etc. -- is that population is an old and tired topic and can't be engaged in without hints of blaming the victim to outright racism. It's sad but real...For good or ill, when the immigration issue is added, the population issue becomes further tainted." -- a leader in a population organization

"I can't get into the subject of immigration, which is important but about which I am personally conflicted since I have family members who are immigrants." -- an activist in a national population group

"[We don't] engage on the issue of immigration because birds don't recognize borders and immigration in our country won't do anything for the bigger problem of world population...The immigrants who come here quickly learn to limit their families in order to have the chance to have the better life that fewer children can offer. Studies have shown that within a generation they learn that they don't have to have huge families and become Americans. I actually heard that we, as a nation, have attained population stability." -- a leader in a state chapter

I conclude after these first 73 conversations that, nearly 50 years after the first Earth Day, the goal of U.S. population stabilization in pursuit of domestic ecological sustainability remains disturbingly elusive.

Of particular importance here is that many environmentalists don't appear to value domestic ecological sustainability enough to publicly promote immigration policies that might make it possible, somehow viewing the population issue as a singular global issue rather than a widespread local one.

I welcome an email from those of you with insights to share as a person with environmental credentials as an educator, writer, organizational leader, scientist or a person with other connected professional experience.

ROB HARDING

0 notes

Text

Response to Rob Harding’s NUSA Post

It is discouraging to read of the tight grip that political correctness/social justice ideology/ identity politics has on the thinking of these environmental leaders. The replies from the academics were particularly depressing. Keep in mind that they are competing at major universities with the campus thought police who actually believe that they should have veto power, based on their standards of approved thought, over who may or may not be invited to speak on campus. Roy and Leon Kolankiewicz discussed the increasing prevalence of social justice ideology among environmental leaders in their 2000 Journal of Policy History article on the retreat of environmental groups from the population issue.

Apparently, it has never occurred to these leaders to read any good newspaper and learn that immigration is to a considerable extent driving the surge of populist, nationalist, far right movements both here in the U.S. and in Europe. Polls have shown that immigration, political correctness, and fear of “cultural displacement,” particularly among the white working class, put Donald Trump in the White House. Migration from sub-Saharan Africa, the Arab world, and from as far away as Afghanistan has shifted E.U. countries to the far right. Angela Merkel may yet fall victim to her decision in 2015 to allow in 800,000 mostly Syrian refugees. The E.U. may itself collapse. The success of right-wing politicians is the last thing these leaders want but is the one thing that is most likely to emerge should the policies of unlimited migration of the world’s poor into the global north be adopted. I’m not certain that their ideological blinders permit them to see this, but it’s demonstrably true and many polls bear it out.

These leaders apparently believe that Americans should lower their fertility to allow more Third World migrants into the U.S. Try selling that idea to Joe Sixpack and see how far you get. The fact that the multicultural environmentalists entertain such ideas shows how out of contact with political realities they are. In a peculiar way these two groups, the social justice left and the anti-immigrant right, feed off and energize each other. Each ensures the growth and survival of the other. For good or ill, a lot of politics works like this.

I don’t believe there is anything that can be done about the cooption of the population/environment movement by the social justice/identity politics left. There is no changing it. This leaves people whose main concern is population, and not immigration per se, in a sort of political no-man’s land. But for anyone whose chief concern is endless U.S. population growth, there is no where else to turn but immigration organizations like NUSA and CAPS. I for one am turned off by Trump, and the loonies who have embraced and enabled him, Hilary Clinton’s “deplorables.” The separation policy at the border is a total public relations and policy disaster. The failure of the immigration reform movement to loudly and forcefully condemn it as such hurts us with reasonable people.

I planned at one point to write about U.S. population/immigration and may yet do so. I think the approach would be like Edward C. Hartman’s Population Fix: Point out where we are headed; what the future will look like; ask, “Do we want this?”; and let readers make their own decisions about joining NUSA, CAPS etc.

Hope you find this useful.

Fred W. Johnson

0 notes

Text

CHRISTMAS LETTER 2017

This letter is way over the top. There are three sections, my travails, politics, and predictions. My recommendation: Skip the travails and go to the next two. Trump’s recent complaints about the FBI are laying the groundwork for dumping Mueller and Rosenstein. Trump’s tactics are unprecedented in American history, undermining public trust in basic institutions like the press and now the FBI as a pretext for “executive action.” He’ll be dumped in 2020 and possibly the Republican congress sooner. See my comments under Predictions.

There was lots of excitement in 2017. Just like in 2015, I paid an unscheduled visit to Alta Bates Hospital. Same problem as before: bugs got in my PICC, the infusion line through which I pump the TPN that keeps me alive. (A PICC, or peripherally inserted central catheter, is for infusing TPN (total parenteral nutrition,), liquid “food” pumped out of a plastic bag through an infusion line into my vascular system to substitute for food ingested through the normal route because my gut is sickly. I do this every night.) It wasn’t bacteria this time but fungi, an infection called “fungemia.” These little buggers are floating around always and everywhere just like bacteria. How did the fungi get into my blood stream? Through the opening in the clave used to hook the pump to the infusion line. It’s the only way. Once the bugs get in, they go straight into the bloodstream right along with the TPN. Worse, they “colonize” the PICC line, growing in a warm dark place where the immune system can’t get to them.

Major symptoms this year were less severe than the sepsis in 2015: low grade fever, rapid pulse, mild malaise. Nicki, a nurse at Herrick hospital, coached me during one of my weekly PICC dressing changes on the fever (101.4) and heart rate (above 90 bpm) levels indicative of blood infection. The fever had been going on for some time and now my heart rate was also elevated, so after I went home and thought about it, I returned to the hospital, just a block away, to have my blood drawn for culture. Two days later, I got a call from the doctor: “You have a fungal blood infection; they’re waiting for you at Alta Bates Hospital; get there as soon as you can.”

The treatment was simple: One daily infusion of 250 mg Diflucan, an anti-fungal, over 90 minutes for the three days I was in the hospital and for up to 10 days afterward as an outpatient. Also pull the PICC line where the bugs hide out. I could have done all this outpatient but doctors want you in one spot, so I spent three days inpatient. Compared to the bacterial sepsis two years ago, fungemia is a cakewalk. I was never really that sick. Had Nicki not commented, I might have gone on weeks longer not realizing I had a potentially serious infection.

I also paid two visits to Alta Bates ER on the July 4th holiday weekend. Severe back pain this time. I have a developmental anomaly; one of my intervertebral discs just never became a real disc. This is the presumed reason I can’t sit for long. X-rays and MRI’s show a strange-looking structure where a disc is supposed to be. Is that thing really in me? When the mattress atop the box spring sags even the slightest bit after years of use, my back senses the mis-alignment and generates pain far in excess of what seems justifiable or tolerable. This is the third time in 12 years of such, so I have experience with it, but this time was so bad I couldn’t get to the mattress dealer before I became more or less incapacitated.

I slept on the floor to avoid a mattress that looked perfectly fine. Monday, July 3ed, I couldn’t get up off the floor and walk to the kitchen. After a struggle and realizing the pain was getting worse not better, I called 911. The fire department arrived so fast I didn’t have time to crawl on all fours to the door while still talking with 911. The firemen banged on the door, taking me and the gurney down three flights of stairs; strapping fellows those firemen. When one asked how I got to the door, I said, “I put on my track shoes and sprinted, how do you think?” With little appreciation for my humor, we trundled through the Berkeley streets while they quizzed me on my demographics and shot me up with something that made my head spin AFTER we arrived at the ER when I no longer needed it.

Ninety minutes later I’d been given a shot of Dilaudid the brand name for hydromorphone, an opioid pain killer, and scripts for same and Valium, a benzodiazepine tranquilizer/muscle relaxant. I wasn’t too sure about becoming a dope addict until I got a new bed, but at least I could walk. To get to the CVS pharmacy and then home, I used the Uber app I had downloaded two days before for just this situation. It worked great; a driver picked me up in no time; followed by a comfortable ride to the pharmacy ….where they were out of hydromorphone in a country overflowing with opiods! Was half of Berkeley high on it for the holiday? Back to the ER where I asked the clerk to ask the doctor could he prescribe a different pain killer? The doctor couldn’t, and said the muscle relaxant would do. Okay, back to the CVS, get the Valium, and finally home.

Next day the 4th, the same problem all over again. I couldn’t walk. Same drill: Call 911, say hello to the firemen, “I hoped I wouldn’t see you guys again so soon, but they didn’t give me a pain killer yesterday, so here I am,” and find a doctor more forthcoming with pain scripts. Getting home, I struck up a friendship with an Algerian Uber driver, who agreed to drive me on errands until I felt safe enough to drive or walk myself. Next day, Wednesday, we drove to the mattress discounter and bought the firmest one in the place. It was delivered Thursday. Saturday morning, after two nights on the new mattress, much relief finally. The nightmare was over, most of the meds untaken. Long-term solution: Buy a new mattress after 7-8 years use, at least a year before it’s time for a new on.

Medical billing is notoriously slow. Just last week I got a bill for the ambulance ride to the hospital on the second day, July 4th. To go less than a mile, they wanted $2,419.42. Outraged, I called the 800 number and asked why I was billed for the second day, but not the first? Molly, the billing agent, looked this up and told me that there had likely been a coding problem and that my supplemental insurance had probably covered the second ambulance ride just like the first. Relief! When we were done with the transaction, Molly asked if there was anything more she could do for me. I said, “You just saved me $2,400, what more could there possibly be? ” We parted on good terms.

Last year I mentioned two articles I was writing on the weighty topic of whether climate causes civil war. Note that interpersonal violence, better known as violent crime, goes up with temperature; people lose their temper when it gets hotter. This is not in dispute. There is even a study showing that retaliation for hit batters in baseball goes up in hot weather. The dispute is about whether political violence, that is, coups d’état, revolutions, armed insurrections, etc., are more likely to take place as temperatures rise. I had written a story for a science writing class about 3,000 words long focusing on the Syrian civil war including the climatology involved, the relevant history and politics of the Arab Spring, and governance of Syria, which, needless to say, is bad indeed. There was also a second article, more than twice as long, about the general problem of climate and war. This has relevance for a warming world, of course, but is based on historical data from years in which the temperature was above normal due to natural variation. In warmer years was there more civic violence? Interestingly, there was an ongoing dispute among peace and conflict researchers about just this question.

Meanwhile, I ran across a call for science manuscripts at the Atlantic Monthly, that bastion of American liberalism. The somewhat flippant tone of the request made me wary about just how serious they were about the science, but this was the Atlantic Monthly, so I decided to try them out. Having spent so much time on the long story, I wanted to know what chance it stood of finally seeing the light of day. After too much time polishing them, I emailed to the editorial staff links for both articles on my Tumblr blog. Bad idea. They politely told me they would “Take a pass on these.” At least they seemed to have read them, but the feedback I had hoped for on how to make them publishable, especially the long one, was not forthcoming.

Pulling myself together after the rejection, I thought, “Well, these people are looking for infotainment, not science,” and sending both articles was really dumb, no matter how much I wanted the feedback. There is really no way to know which article was problematic although it was probably both. What’s ironic is that the long article is really better even though it’s too technical because it demonstrates that three UC, Berkeley professors who claim their data show that climate causes civil war, are flat out wrong. There is agreement among other researchers that what the data does show is that when crops fail because of heat or drought and there are marginalized groups within a society, only then is civil conflict more likely, as these excluded groups revolt. This was very much the situation in Syria, where a six-year drought ignited a powder keg of political repression, triggering the worst civil war in this century. Climatologists are in general agreement that climate change played a role in the drought, placing stress on people by drying up their crops leading to food shortages and leaving no choice but to revolt in the face of a government that refused any aid at all. Now, after more than seven years of war, the Assad regime, with Russian assistance, has crushed that revolt. The Russians are supposed to be the revolutionaries. Not under Putin.

Writing about this now, I think I know what I did wrong. Maybe I’ll go back, write a new draft and try again, setting aside for a while my latest project.

Politics:

Last year, I said Hilary lost the election by ignoring voters who used to be solidly Democratic. The Reagan Democrats, the Forgotten Man (and Woman), shook the political landscape. But this was really nothing new. For some time, political scientists have studied why working class and rural whites vote for Republicans against their own economic interest. Trump lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million, and won in the Electoral College on the basis of fewer than 80,000 votes cast in swing states that were once safely in the Democratic column, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. A small percentage of Obama voters switched to Trump in those states, putting him in the White House. Even in the midst of the best economy in years, voters who switched from Obama to Trump are still looking for but not finding a better job, a higher standard of living, and relief from the large impersonal forces of automation and globalization that define our time. But if disappointed by Trump, those voters will turn against him in 2020 if the Democrats find the right candidate. But the Democrats are so divided they just might fail even with two or three more years to work at it.

As late as Spring 2016, a clueless Paul Ryan, Speaker of the House, was touting the Holy Triad of Wall Street Republicans: free trade, open borders, and tax cuts. Trump ran against all three and won an Electoral College upset. Now he is about to sign a tax plan made for corporations and the rich that betrays his populist base. The real purpose of the tax plan is to create deficits that can be used as a pretext to defund Medicare and Social Security, programs Trump promised his supporters he wouldn’t touch. Why does he sell out his base? Because the fat cat donors who call the tune in the Republican Party want the tax cuts they bought with their campaign contributions. Some things never change.

Predictions

The speculation that Rex Tillerson will quit the State Department or be fired next month was quelled somewhat by Tuesday’s State Department briefing at which Tillerson talked like a man with plans who was looking forward to next year. If Tillerson leaves or is ousted, then Mike Pompeo, now CIA director, becomes Secretary of State; Tom Cotton, now a Senator from Arkansas, takes the helm at CIA; and Hilary can run for the open seat in her former home state. Pull for Tillerson because he is moderate and pursues diplomatic solutions. Both Pompeo and Cotton are inexperienced, have military backgrounds, and are hard liners. Their ascent would tilt the scales toward war.

Trump will fire Mueller and start a national furor, perhaps soon. You might think that Trump would find relief when he fires Mueller, but there may be only short-term comfort in the firing given Trump’s history of sexual misconduct and the new political climate on harassment and groping. Just ask Roy Moore.

If the presidential election were held today, Trump would be trounced in the popular vote and would probably lose the Electoral College. But the Democrats would have to win at least 55 percent in the popular vote to have sufficient margin to win the electoral vote in states where they were weak in 2016 including Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Can the Democrats overcome their internal divisions, much like those in the Republican Party, and find a charismatic candidate who will excite the country the way Trump excited the Forgotten Folks? Don’t bet on it.

There are too many unknowns to call the Senate, now precariously in Republican hands 51 49. The number of Senators up for re-election favors the Republicans, just 9 seats to the Democrats’ 24. But “passion,” which is hugely important in the emotional business of political campaigns, favor the Democrats: energy, anger, and enthusiasm. Also, midterm elections always hurt the sitting president’s party, the Republicans in 2018. Ditto for the House races below. Bottom line, the Republicans keep the Senate.

That energy might win back the House for the Democrats, but jerrymandered districting favors the Republicans. It will take high turnout and lots of atmospherics to overcome that advantage and win the 25 additional seats required to win control of the House. Bottom line: The Democrats win back the House.

We will know about all these predictions except the presidential when next we meet.

Oh, yes. This will be another year of drought in California after a two-year hiatus from the three years of extreme drought before the hiatus. Some things never change.

Happy Holidays,

Fred

0 notes

Text

CHRISTMAS 2016 LETTER

I just read over last year’s Christmas missive, the letter at least one of you didn’t receive in the mail until March. When I first got word that some of you hadn’t gotten your letter, I walked to the Berkeley Post Office, one of the few U.S. Postal Service offices with a permanent street-person encampment reminiscent of the Occupy Wall Street camp ins of 2011. The so encamped were protesting the planned closure of the Central Berkeley Post Office even though most of the protesters have no permanent address so don’t the don’t get mail and can’t afford a post office box either.

Once I got past the encampment and into the lobby, I talked to a certified U.S. Postal Service clerk, who said he and his fellow staff have one billion mail pieces to deliver before Christmas and can’t be expected to get all of them right. I considered switching my voter registration to Republican, but held off.

Think of it, there are 324 million souls in the U.S. That’s only three pieces of mail for every man, woman, and child in the country. Surely, the Postal Service can do better than that; with 617,254 employees in 2015 according to Wikipedia, that’s 1,620 pieces of mail per employee. Seems like a lot, but machines do some of the work, is the post office forbidden from using labor-saving devices?

So this letter is something of a crap shoot. Might get there might not.

In 2015, after wasting most of a year writing a proposal for which the data in hand would not support the envisioned analyses, I decided to try my hand at writing. I had already written about drought in the West, and 40,000 words of a memoir mostly about my epic medical problems. Publishers limit a first memoir to 80,000-90,000 words, and I was going to exceed that. But I didn’t really like what I had written and didn’t like writing it. Maybe some day, but not now, and done much differently. I was looking over the courses UC Berkeley Extension offered in Spring last year and ran across Science Writing, mostly by accident. I signed up. Like most UC extension courses, it was a lot of work, but worth it. Jennifer Huber, a physics Ph.D, taught the course. She had worked at UCSF in imaging; probably living in the soft money world of grant-to-grant funding where I worked for 18 years. She has been writing for 10 or more years now and has it all up on a web site. She was a tough grader and superb editor. I had to shed my technical writing style for something more compelling to the educated lay reader.

She liked my final project, “Climate Change, Climate Cycles and the Syrian Civil War,” and suggesting “pitching” it to a publisher. That was in the first week of June. I thought I needed to establish that climate is in fact related to civil war before writing about a single example of climate actually causing civil strife. That was a big mistake. Six months later, I’m still polishing the article, having stumbled into an academic controversy that got into the press. Does climate cause civil war? Not climate change, though the topic has obvious relevance for that inevitability, but just normal variation, which can at times be extreme; think of the 1930s Dust Bowl. A group of UC, Berkeley economists says, “yes;” a group of European political scientists says, “no.” I’m still undecided despite plowing through many journal articles.

I’ve spent more time on this than on any writing task since my dissertation, often going far astray into topics like Bayesian statistics. Lesson: Keep it simple. It’s already complicated enough and the average intelligent reader isn’t interested in esoterica. Most science articles for the non-specialist are about one journal article; I’ve read scores plus additional textbook material for this article, enough to write a book, though I never intended to do that. I have one set of notes that’s 76 single-spaced pages long, mostly copy and paste material from various articles, but also my “ideas.” I never looked at it again after building the thing up. There are other sets of notes not so epically long. Didn’t look at those either. Regardless of the notes, at some point, I’ll try to market what I have. Selling is not my strong suit. Tune in again next year.