Text

Samurai Flamenco in Hindsight, Episode 1: “Samurai Flamenco, Debut!”

“The cold open doesn’t hide the fact that Masayoshi is naked, but it quickly pulls our attention away so that going into the opening, we’re focused on Masayoshi’s conviction: whoever this naked weirdo is, he is dead serious. The episode version turns that on its head: whoever this dead serious guy is, he is a naked weirdo.“ - from the write-up

Official English Episode Title: “Debut of the Samurai Flamenco” (Crunchyroll) Japanese Title: サムライフラメンコ、デビュー! (Samurai Furamenko, debyū!)

Original Air Date: 10/11/2013 (also shown at the “noitaminA October Cour Special Premium Preview ” event on 9/28/13)

Episode Director: Ōmori Takahiro Episode Script: Kurata Hideyuki Episode Storyboard: Ōmori Takahiro Animation Directors: Yamada Masaki, Yamamoto Wataru

Check out the intro post for the Samurai Flamenco in Hindsight project here.

Spoilers start after the cut!

Navigation

Episode Summary

"The Design’s Slightly Different for the Movie!”: Repetition in “Samurai Flamenco, Debut!” and Beyond

In Plain Sight: Gotō and His Girlfriend the Second Time Through

Broadcast vs. Blu-Ray - Are the Improvements to the Blu-Ray version of This Episode Enough to Justify Seeking it Out?

Scattered Observations

Episode Summary

Returning from a late-night trip to the convenience store near his apartment, off-duty policeman Gotō Hidenori (Sugita Tomokazu) stumbles on a handsome young man sitting in a dark alley. When Gotō demands he identify himself, the other man stands and declares himself an "ally of justice" — just as the light from a passing car reveals that he's completely naked. Confused and flustered, Gotō tries to arrest the "pervert," the "pervert" pleads his innocence, and wackiness ensues until Gotō's hastily-thrown cigarette lands on the clothes the young man had been sitting on, turning them to ash. Feeling responsible, Gotō accompanies him to a swanky high-rise apartment; there, he learns that the would-be "hero" is Hazama Masayoshi (Masuda Toshiki), an up-and-coming model still pursuing his childhood dream of becoming a Kamen Rider-style defender of justice, just like the ones he (and Gotō) grew up watching on tokusatsu (toku) TV shows.

Although Gotō finds a lot of holes in Masayoshi’s plans — and is more than a little frustrated by Masayoshi’s eccentric personality — he quickly warms to him over the course of the evening. The feeling seems mutual, as Masayoshi (urged by his manager to improve his conversational skills) promptly tracks Gotō down at work and invites him for another round of toku shows and curry rice.

Despite Gotō's firm warning to stop playing vigilante, Masayoshi again ventures out as "Samurai Flamenco” — and promptly ends up on the run from a group of mildly delinquent middle schoolers who decide to hunt and pummel the “freak” for kicks. Masayoshi makes a desperate call to Gotō for help — but just as he’s about to tell Gotō where he is, Masayoshi suddenly finds his heroic resolve and decides to confront the teens a second time. Samurai Flamenco endures a beating, then rises to deliver an impassioned speech, reiterating his belief that turning a blind eye to minor crimes and misdemeanors only causes greater suffering — and that it’s especially cruel to be indifferent to the futures of kids like them. After a moment of stunned silence, the teens strike Masayoshi again, knocking him to the ground, but quickly scatter when Gotō arrives on the scene. Gotō initially chides his friend, but when Masayoshi asks if he’s closer to achieving the hot-blooded heroism he aspires to, Gotō softens, smiles, and agrees.

A final montage shows Samurai Flamenco continuing to confront petty lawbreakers throughout the city, that multiple videos of his escapades are starting to pop up on video sharing sites, and that whether online or in person, all eyes are on Masayoshi…

"The Design’s Slightly Different for the Movie!”: Repetition in “Samurai Flamenco, Debut!” and Beyond

Returning to “Samurai Flamenco, Debut!” for this retrospective, with all of Samurai Flamenco in the rearview, the first thing that struck me was how much of the series finale revisits the series premiere. Some aspects of that are obvious, like Masayoshi’s opponent, Sawada Haiji, being one of the teens he confronted in the first episode’s climax, and our hero being naked at a wildly inappropriate time. (To be fair, at least this time it’s not in public.) And while the official title for English streaming hides the resemblance, the literal Japanese titles for these two episodes, “Samurai Flamenco, Debut!” and “Samurai Flamenco Naked!!” — are clearly meant to mirror each other.

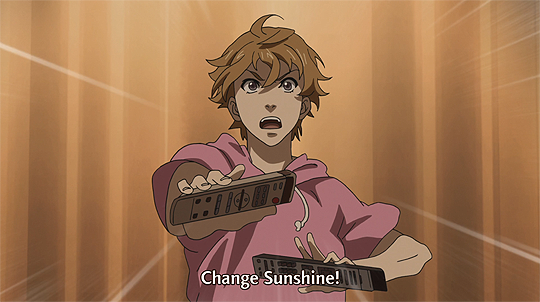

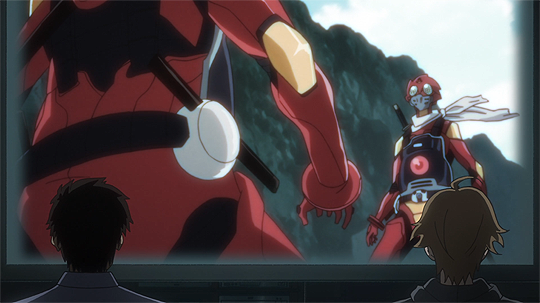

But there are more subtle connections as well. For instance, both episodes are set chiefly at Masayoshi’s apartment — and in a neat trick, the blown-up version we see in episode 22, with its dark palette, heavy shadows, and rough condition, echoes the alley where Masayoshi and Gotō first met, as if to combine those two settings into one. Likewise, while Masayoshi and Gotō’s conflict in the finale is most memorably foreshadowed by Kaname’s line in episode three that “convincing a friend they’re wrong is the hardest thing you’ll ever do,” episode one hints at what’s to come with the face-off in the Harakiri Sunshine movie Masayoshi and Gotō watch. If you listen to the movie’s dialogue, the conflict between Sunshine and Sunset is broadly parallel to the situation Masayoshi and Gotō find themselves in in the finale — and onscreen, the two sets of characters are visually aligned, with Masayoshi on the same side as Sunshine as he calls out to Sunset, projected in front of Gotō.

Structurally, both one and episode 22 begin with a scene that either repeats an earlier one or is itself repeated later, albeit with important differences in each case. (More on that in a bit). And if you want to get cute about it, the outfits Masayoshi and Gotō wear during the epilogue use roughly the same color scheme as those they wear in episode one, with Masayoshi in a purple hooded jacket and Gotō in a long-sleeved zip-up that’s the same pale blue as his aloha shirt.

What also struck me, though, was how much episode one makes use of repetition within the episode itself. Masayoshi brings Gotō to his apartment twice; there, they eat curry rice twice and watch Harakiri Sunshine twice. Gotō twice warns Masayoshi to lay off the vigilante stuff, and Masayoshi twice agrees that he will. Masayoshi then proceeds — twice — to head out as Samurai Flamenco and get in enough trouble that he needs to call Gotō to come rescue him, repeating what seems like it’ll soon become his catchphrase: “Gotō-san, I messed up!” And then there’s the post-credits montage showing four separate instances of Masayoshi confronting petty lawbreakers, and Konno viewing a “NuTube” page documenting even more of Samurai Flamenco’s appearances.

On the visual level, certain shots and framings are repeated, too — and not just obvious, utilitarian ones. Most strikingly (since it’s a little bravura for Samurai Flamenco), the two short sequences of Masayoshi modeling use the same setup: a close-up that “pivots” into a full-body shot seen in landscape view, followed by a long shot establishing the setting. In a similar unusually flashy bit, Masayoshi and Gotō entering Masayoshi’s apartment is shown through a series of jump cuts seen from overhead, and when Masayoshi’s flashes back to his encounter with the drunken salaryman, that’s also how the man’s jaywalking is depicted. Later, we get a pair of matching shots in which Masayoshi peers into his closet, followed by a panning POV shot across his clothes to the spot where his belts are hanging — the first time in his backstory flashback,

the second when he describes the discovery of his second hero suit.

And when Samurai Flamenco confronts the drunken salaryman, we see the man framed between Masayoshi’s legs, just before the cut to the man punching our hero —

a setup which is repeated after the commercial break with Masayoshi pacing back and forth in the foreground as Gotō listens to him monologue about working his way to up fighting big-time villains.

It’s at this point, of course, that Gotō interrupts to point out the flaws in Masayoshi’s plans, and the shock stops Masayoshi in his tracks as surely as the salaryman’s punch did. The visual similarity underscores that both Gotō and the salaryman challenge Masayoshi’s heroism (one on theory, the other on practice) — and this isn’t the only way time the show connects these two characters. It’s easy to overlook, but when first Gotō stumbles on Masayoshi, he’s not just smoking in the same no-smoking area as the salaryman, but also jaywalking at the same crosswalk. (The BD version corrects the backgrounds in Masayoshi’s flashback to make this clearer.)

This happens multiple times in episode one: one character will do something, and then another character repeats that action, stepping into their role in a similar scenario. Gotō encounters the delinquent teens outside the convenience store; a little later, so does Masayoshi, as Samurai Flamenco. Masayoshi visits every police box in the area to track Gotō down; later, after Masayoshi’s frantic call for help, Gotō decides to check every phone booth in the area until he finds him. In the Sunshine movie clip, Sunshine faces off against Sunset and challenges his heroic ideals; the exact same lines are used when Masayoshi “meets” Sunshine in his imagine spot, putting Masayoshi literally and figuratively in Sunset’s place.

So Samurai Flamenco uses repetition a lot in its first episode, but to what effect? Well, several effects, actually. Straightforward repetition helps to establish what’s normal in the world of the show (casual lawbreaking), and what becomes normal (Masayoshi and Gotō hanging out); likewise for character traits (Masayoshi can’t stop/won’t stop fighting “evil”) and the daily rhythms of character’s lives. By the end of the episode, we have a pretty good feel for what Gotō’s shifts are like after all those scenes at the police box, for instance — and we don’t need to be told that the work can be boring because we’ve seen Gotō yawning and staring blearily into space multiple times.

And the show makes similarly versatile use of repetition with a difference. Sometimes, putting two characters in the same scenario highlights differences between them (Masayoshi moved by his Justice to confront the kids as nuisances while Gotō just scowls and goes on his way); in other instances, it exposes surprising similarities when two seemingly different characters unwittingly or unknowingly mirror one another (Gotō and the drunken salaryman). We’ll see both versions frequently of this over the course of the show’s run: think about all the “Flamencos,” each distinct from Masayoshi in some important way, and all the times Masayoshi is unsettled when he recognizes a version of himself in his antagonists. (And not just that one really obvious one.)

An instance of repetition with a difference that I think is particularly worth exploring is Masayoshi and Gotō’s first meeting, which we see first as a cold open before the title sequence, then in context, after we’ve followed Gotō through his day up to the point of the encounter. In an episode full of flashbacks (how Masayoshi ended up naked in the alley, the discovery of the second Samurai Flamenco suit, etc.), the two versions of the alley scene are the only time we actually revisit material that we’ve already seen. Curiously, though, the in-episode version is not just the cold open replayed, nor is the cold open just a slightly more streamlined version of what we see after the title card. They both use the exact same dialogue, and some of the same footage, but differ significantly in their framing and editing.

(Want to follow along? The cold open runs from approximately 00:00 to 00:42, while the in-episode version is roughly 04:00 to 4:33.)

Let’s start by comparing the two scenes, beginning with the first shot they have in common. Within the episode — that is, after the title card — this comes shortly after Gotō leaves the convenience store. The sequence begins with Gotō noticing the pack of cigarettes on the ground. (Although we don’t quite see it onscreen — and I’ve single-framed through the cut enough times to be sure — the implication is that the drunken salaryman drops them when he punches Masayoshi.)

In both versions of the Masayoshi/Gotō meeting, what first catches Gotō’s attention is the light from the monorail passing overhead reflecting off the cigarette pack. However, in the cold open, we see the close-up of the cigarettes on the ground first, then a slight low-angle close-up of Gotō, with the monorail zipping offscreen in the upper right. The episode version reverses this: after a unique ground-level shot showing the cigarettes just in front of Gotō’s approaching feet, we cut to the close-up of Gotō, then the cigarettes, then back to Gotō. Both versions then synch up for a moment, as Gotō hears a cat screeching and some commotion off to his right (screen left).

The cold open cuts to a shot of the alley where Gotō will eventually find Masayoshi, with the camera pushing in toward the entrance.

The alley is considerably darker than the street, but we can see crates and garbage bins at the far end, arranged in such a way that it’s clear this alley intersects with another one. The following shot is positioned from within that other alley, showing propane tanks in the far background and, closer to the camera, the corner of a building. A moment later, Gotō’s head and shoulders peek around it.

Now we cut to what seems like Gotō’s perspective: a long shot of the alley he’s looking into, the entrance to the adjoining street visible in the background. In the midground of the shot, Masayoshi is just visible behind some boxes and a trashcan. After a moment, his head and shoulders move forward slightly; we can guess he’s heaving a sigh.

We return to the earlier shot of Gotō, who makes a surprised noise and raises an eyebrow, confirming for the viewer that he saw Masayoshi’s movement, then it’s back to the shot of Masayoshi, now lit up by the headlights of a passing car spilling into the alley. Another cut brings us closer to Masayoshi, and we can clearly see his bare shoulders, chest, and legs — along with his downcast eyes.

The scene dims as the car pulls away; Masayoshi turns and looks toward the camera — toward Gotō — and his mouth drops open in surprise. Gotō, in close-up, makes a startled noise; he knows he’s been spotted, too.

Now we get our first good look at Masayoshi up close: we can see that he’s hugging himself tightly behind that trashcan, and that he’s wearing a miserable expression. We return then to the close-up of Gotō, who slowly removes the cigarette from his mouth and asks Masayoshi to identify himself.

We need to pause here for a moment and get caught up with the episode version, because it eliminates many of the shots I’ve just described, starting with the establishing shot of the alley entrance. Instead, the episode version goes directly from Gotō glancing at the alley to him peering around the corner within the alley. Then it dumps the first shot of Masayoshi in the alley and the corresponding cut of Gotō noticing his movement, jumping directly to the car illuminating Masayoshi. We do get the close-up of Gotō reacting to Masayoshi noticing him, but not the matching sad-faced Masayoshi. Instead, in a single unbroken shot, Gotō is surprised, then removes the cigarette from his mouth. But, instead of Gotō asking Masayoshi who he is in the same shot, we cut back to the earlier framing of Gotō in medium shot as he peers around the corner.

In other words, Gotō performs the same action — removing the cigarette from his mouth and posing his question — but at a significantly greater distance from the camera, and so he appears smaller in the frame.

(left, cold open; right, episode version.)

Got all that? Good, because here is where the two versions really start to diverge. The cold open goes to a bird’s-eye view overhead shot, with Gotō peering around the corner at the far left of the screen, and Masayoshi at the far right.

We remain on this shot through nearly their entire dialogue exchange, until Gotō calls Masayoshi “suspicious,” asks if he’s a thief, and steps around the corner and into the alley itself. As Masayoshi insists Gotō is mistaken, we switch to a shot from roughly Masayoshi’s perspective, showing Gotō pulling back in surprise at the opposite end of the alley.

Masayoshi begins to rise up into the shot, and in such a tight close-up that Gotō is quickly and completely hidden by the back of Masayoshi’s head coming up through the bottom of the frame.

Cut to a shot, roughly from Gotō’s perspective, of Masayoshi standing in the alleyway. It’s relatively short in duration, giving us just enough time to register Masayoshi’s nakedness and the truck in the background before we cut to the final shot of the sequence — a chest-up shot of Masayoshi staring into the camera with an earnest, determined expression.

Dramatically backlit in gold, his voice now full of conviction, Masayoshi declares himself an “ally of justice” (“superhero” in the official subs). The light dwindles and we fade back to the alley’s previous darkness. Cue opening credits.

Now let’s jump back to see how the episode version ends the sequence. First, it does NOT go for a bird’s-eye view for Masayoshi and Gotō’s dialogue exchange. Instead, after Gotō asks “Who are you?”, we cut back to the earlier shot of Masayoshi behind the trashcan and crates.

In terms of camera position and framing, he’s shot in the same way as Gotō behind the corner was — and once Masayoshi delivers his line that he’s not a suspicious person, that’s exactly the Gotō shot we go back to.

Just like in the cold open, Gotō insists Masayoshi is, in fact, suspicious, asks if he’s a thief, and steps around the corner — but this time, we see him do it from the front, as if from Masayoshi’s perspective.

(left, cold open; right, episode version.)

The framing this sets up is exactly like what we saw in the first version, so it would be reasonable to expect the next thing we see to be Masayoshi’s head rising up through the bottom of the frame, concealing Gotō. But that’s not what we see. Instead, the shot ends when Gotō pulls back in surprise. Masayoshi rising to his feet is instead handled as a medium close-up of Masayoshi, seen from the front. The camera follows him, tracking his head and shoulders upward, until Masayoshi is perfectly centered in the frame. We see him from the chest up, face earnest and determined, dramatically backlit in gold.

You get it, right? The same setup as the final shot of the cold open. But the timing is different — and so is the editing.

Since this is a comparison, relative measurements will probably be more useful for conveying how these scenes end than “X seconds” and “Y frames,” so I’m going to describe these last two sets of shots with regard to Masayoshi’s final line: “I am…an ally of justice” (Boku wa…seigi no mikata desu). In the cold open, we hear “I am” as the back of Masayoshi’s head rises into the frame. The brief pause (“…”) covers both the end of that cut and the entirety of Masayoshi’s full body nude shot, meaning we don’t spend very much time on these two images — long enough for both images to register, but not enough for either to feel emphasized. When we get to the medium close-up, though, that perisists through all of “an ally of justice,” and is held on for a solid beat afterward. Relatively speaking, we spend a long time focused on Masayoshi’s determined face, enough that the light from the truck’s headlights can fade and another passing car provdes another pulse of illumination before we return to the alley’s earlier darkness. And in a sense, we stay fixed on his serious face into the opening credits, since the very first image there is another, even tighter, close-up on Masayoshi, still centered in the frame, now against a field of stars.

The episode version keeps the same pacing, but reverses the order of the shots. This means that the dramatic close-up takes place over “I am” and the pause,and that the shot that takes place over “an ally of justice” — the one that’s lingered on — is — yes —

Masayoshi's full-body nude shot. What’s more, since the vehicles just beyond the alley are still passing by at roughly the same time, this means that the close-up on his determined face only gets one shot of dramatic but obscuring backlighting, while the full-body shot is illuminated twice, calling attention to Masayoshi’s nudity. The cold open doesn’t hide the fact that Masayoshi is naked, but it quickly pulls our attention away so that going into the opening, we’re focused on Masayoshi’s conviction: whoever this naked weirdo is, he is dead serious. The episode version turns that on its head: whoever this dead serious guy is, he is a naked weirdo. Appropriately enough, what the final shot gives way to the second time around is utter wackiness and misunderstandings, underscored by wildly tilted angles, lighting and framing that emphasize both Masayoshi’s nakedness and Gotō’s outsize reaction, and, for the first time in either version of this sequence, music — a comic action track, “Dash,” that adds to the madcap atmosphere.

At this point, it should be clear that the two versions of Masayoshi and Gotō’s first meeting are staged very differently; at the same time, it would be reasonable NOT to notice this during ordinary viewing, since events play out almost identically until the end, and the changes in framing aren’t so marked as to call attention to themselves. As a result, the two versions of this scene essentially overlap — not perfectly, but to the point that the episode version feels like a continuation of the cold open.

The question is less “Why repeat this scene at all?” than “Why not just reuse the same footage?” Why put time and limited resources into making two separate iterations with unique artwork when you could just double up on the episode version, trimming it a little for time so it can work as an effective pre-opening tease? I think you could justify that decision in a variety of ways, and I don’t think the answer I’m about to give is necessarily “the right one.” But what’s most interesting to me is the subtly different impressions that the cold open and episode version give as a result of their unique formal features — which includes but is much more than just how they end.

The cold open’s framing works to establish Samurai Flamenco’s setting as a familiar real-world space, one that’s authentic not just visually, but experientially. Instead of being introduced to Yukimachi via a long shot of tall buildings seen from a distance, we start out right at street level, with Gotō seeing the cigarette pack on the ground — and when we do see buildings, they tower overhead, as if we were standing in that space.

With Gotō as our surrogate, the space continues to be mapped around us, primarily through editing — shot of Gotō looking, shot of the alley from his perspective, shot of Gotō poking his head around the corner we saw in the previous shot, shot of the intersecting alley from Goto’s perspective — but also camera movement. Even if we don’t take the camera pushing in toward the alley as literally representing Gotō moving in that direction, the push-in still conveys a sense of distance between the camera’s starting position and the alley itself. What I’d emphasize is not the literalness of the first-person perspective, but that 1) the show is taking pains to set up the geography of the the scene, and 2) that it does so from the perspective of someone physically in that space.

Of course, then we get that overhead shot of the alley, a view clearly not aligned with Gotō's POV or anyone else’s, and obviously not an angle from which we’re used to encountering alleyways in real life. As a result, we do lose that sense of direct immersion — but there are tradeoffs: for one; the shot clarifies for the viewer exactly where Masayoshi and Gotō are in relation to each other; second, and more importantly, the bird’s-eye view shows how realistically small and cramped the alley is. An alley is, after all, a gap between two buildings, not a thoroughfare -- but it’s unusual for them to be portrayed in such a way that viewer actually registers the space as confining. Here, the alley appears as a thin band between two steep walls that take up most of the frame, and while the area is neat and tidy, the propane tanks, bottle crates, and ventilation systems jutting out into the alley narrow it even further.

So even though the angle breaks with the literal “man on the street” perspective, the way the space is designed still adds to scene's sense of authenticity — and since we can tell that there isn’t much room to maneuver, and see how little distance there is between Gotō and Masayoshi, this also ups the tension.

Finally, the cold open having Gotō discover Masayoshi more gradually — perceiving his movement, but not calling out until Masayoshi’s presence is confirmed by the car headlights — suggests how difficult it is to see in the darkness of the alley. As viewers, we can pick Masayoshi out almost immediately, because the show isn’t really trying to hide him from us — notice how the shot’s lighting and color draw the eye to that specific part of the frame?

So adding a step to Gotō’s discovery process is important, because it emphasizes how dark this space is from the perspective of someone who’s in it.

Altogether, the cold open positions Samurai Flamenco as a series grounded in ordinary reality, with its “realism” defined by how closely the show tracks with everyday experience — particularly, of urban space. To put it another way, the cold open suggests that while this series will aim for a certain level of visual verisimilitude, its world is “the real world” because its characters live in and move through the kind of spaces that we do in real life. That in turn sets certain expectations for character behavior and what could reasonably happen in this series.

That said, we still have to reckon with how Masayoshi’s declaration at the end is framed. Think of how when Masayoshi’s head rises into the frame, he eclipses Goto, filling nearly the entire visual field;

how the world turns to gold behind him as he speaks; that when he names himself an “ally of justice,” he’s staring right at the camera — at the viewer.

While none of these shots violate the realism of the cold open up to this point (it’s truck headlights that create the gold backlighting effect, after all) these shots are slightly more dramatic, expressionistic, and attention-getting than what’s come before. The resulting contrast makes Masayoshi’s “I’m an ally of justice” feel just this side of uncanny — an eruption of strangeness in the middle of the ordinary that unsettles and disrupts. Put another way, when Masayoshi says that, and it’s framed that way, it feels like something outside what we might usually expect could happen. Now, I’m not claiming this is super-secret foreshadowing that Masayoshi’s desire to be a hero will literally warp the fabric of reality around his wish. That feels like a bit of a reach. But I would say that the cold open primes us for the idea that however ridiculous the hero media Masayoshi is obsessed with can seem, it might just have the potential to change the way things work, and is therefore worth serious attention.

The episode version, of course, upends that when it shifts the focus from what Masayoshi is saying to his full-frontal nudity. Still, as the scene devolves into wacky antics, the gag isn’t so much what Masayoshi is saying as his apparent obliviousness — he’s spouting lines like this while standing naked in a public alley, and even after Goto identifies himself as a police officer who intends to arrest Masayoshi and has told Masayoshi to freeze, Masayoshi’s response is to continue approaching the clearly nervous cop and plead his case.

The joke hinges, in other words, on Masayoshi’s personality. And if we look at what distinguishes the episode version from the cold open, we see that its unique formal features work to emphasize character and relationship development.

As mentioned earlier, the episode version completely removes several shots that were part of Gotō’s discovery of Masayoshi, like the view of the alley entrance and Gotō noticing Masayoshi in the dark, meaning Gotō spots him more quickly, and we get to their encounter that much faster. The overhead view of the alley is also gone, but in this case, the dialogue and action that took place during that shot are still there — just reframed into a shot/reverse-shot sequence alternating between Masayoshi and Gotō. We can still sense physical distance between the characters, since they’re framed in matching medium long shots, are seen roughly from the other’s perspective (almost-but-not-quite Gotō’s view of Masayoshi, and vice-versa), and are never in the same frame together until Gotō insists he’s going to arrest Masayoshi (that is, after the big nudity reveal).

Nevertheless, the space feels subtly bigger and more open than when we saw the buildings boxing the pair in, in part because we’re seeing it broken up into multiple views rather than as a single complete space.

What’s lost in spatial realism is gained in our actually getting to see Masayoshi and Gotō’s reactions to each other during their initial exchange, which were largely hidden in the cold open. To be sure, the visuals align with Sugita and Masuda’s vocal performances, so there are no real surprises here. Still, both characters are instantly easier to understand and relate to because we can see Masayoshi’s alarm at being discovered, Gotō’s caution that has him lean forward (that tilted chin) rather than take another step, Gotō’s irritation that this clearly nervous and at least half-naked guy sitting in an alley has the nerve to insist he’s “not a strange person” — and so on. We have a richer sense of who both of them are, and what their interactions will be like, because of this reframing.

In addition, the visual language of the episode version puts Masayoshi and Gotō on roughly equal footing. The cold open achieved its own kind of balance, giving Gotō the majority of the screentime, but giving Masayoshi the “final word.” Still, it was very clear which of these two will be the main character, because, aside from Masayoshi having the more unique look, he also gets the more impressive framing (again, he ends the sequence center frame, close-up, literally bathed in golden light). But the episode version undercuts the mysterious air Masayoshi had by the end of the cold open, and depicts both Masayoshi and Gotō in almost literally the same way, with the same framing, and roughly the same amount of time spent on each of their shots. This actually continues past the material covered in the cold open: the setup for Gotō’s “A pervert!” — a low-angle tilted shot — is also used to show Masayoshi protesting, just reversing the angle;

then, the shot over Gotō’s shoulder as he insists he’s going to arrest Masayoshi is flipped into one over Masayoshi’s shoulder as he approaches Gotō;

and so on.

In this version, the presentation privileges neither of them, and one way to read that that makes sense in light of everything that comes after is this: while Masayoshi is the lead, Gotō is equally important — not just to “the story” or “the plot,” but to the entire experience of Samurai Flamenco. More generally, the episode version says this series will be driven by characters interacting, (mis)communicating, and responding to the strong personalities around them.

To wrap up this comparison, I suggested that the episode version is poking fun at Masayoshi rather than the at idea that hero media might be worth serious consideration. What I’d add is that it does kind of still do that. Despite his conviction, Masayoshi loses his composure once Goto calls him a pervert, and from this point until the episode’s climax, his interest in heroes becomes a source of humor, while Gotō explaining why Masayoshi’s plans won’t work serves to highlight the ridiculousness of building your life and moral code around Kamen Rider, Super Sentai, and the like.

The show advances both ideas — but it didn’t have to stage Masayoshi and Goto’s first meeting twice to do that. Because it did, and because it avoids identifying one version as “what really happened,” instead allowing the versions to overlap but not exactly, I think that “Samurai Flamenco, Debut!” sets up the idea that both takes are correct: hero media is ridiculous entertainment for children and can’t impact the real world; also, hero media can inspire people in powerful, positive ways, meaning it can absolutely make a difference. Repetition with a difference becomes a way of creating and holding open the tension between these two ideas, both within this premiere episode and across the series as a whole.

Again, I want to stress that repetition does a lot of other things in this episode, and in this series. It’s a versatile tool that Samurai Flamenco makes use of time and time again, and there will be ample reason to come back to it as I work through the other 21 episodes. But looking back over “Samurai Flamenco Debut!!” and thinking about Samurai Flamenco as a whole, I feel like the sheer amount of repetition in this episode also signals how important repetition as a concept will be to the series. I’m thinking, for instance, of the way that genre tropes and formulas become an explicit problem in the show’s long middle arc, particularly the Torture and Flamengers episodes — and how routines, cycles, and being stuck in a rut are problems for several major characters. As with the two versions of Masayoshi and Gotō’s first meeting, the effect is subtle, and more apparent in hindsight than on first viewing, so “foreshadowing” might feel like too strong a word — but if you take into account all the different kinds of repetition in episode one, there’s just so much of it that it’s almost hard not to see it that way.

In Plain Sight: Gotō and His Girlfriend the Second Time Through

One of the pleasures of revisiting Samurai Flamenco is discovering how different the series is on rewatch. It’s not just that you start to spot foreshadowing of late-series twists and surprises; rather, knowledge of what’s to come and how much changes over the course of the show colors your viewing. For instance, until I knew how much more grown-up Masayoshi would be at the end of Samurai Flamenco, I didn’t appreciate just how self-centered and stubborn he was in the first nine or ten episodes — and not just when he’s at his worst during the Torture Arc. Likewise, Kaname definitely had a “trickster mentor” air pre-Flamengers, but when you return to the show’s early episodes after seeing him become more reliable, all his earlier buffoonery starts to look suspect.

Well, maybe not all. He did punch out a Wow Show! host because he got in too much of a punchin’ groove. And there was the time he jumped off a running motorcycle that nearly slammed right into Gotō. And…

But hands down, what affects all subsequent re-viewings of Samurai Flamenco more than anything is the Gotō’s Girlfriend situation. Even the discovery that Masayoshi had reality-warping powers has less of an impact, because while that does explain some things, it doesn’t prompt the complete and total reevaluation of one of the show’s fundamental pillars. Learning about Gotō Girlfriend’s disappearance and how Gotō has coped with that loss does have that effect. Although Gotō was never as straight-laced as a character in his position might be, he was always Samurai Flamenco’s anchor in Normal, setting the baseline for reasonable behavior, expectations, and actions that more eccentric characters played off of. Moreover, as the show’s effective co-protagonist, Gotō was the character we spent the most time with after Masayoshi, including time when Gotō was alone…which was not infrequently spent exchanging messages with his Girlfriend. Conversations with Her were one of the major ways that Gotō’s character was developed — and for viewers to learn what was on his mind when Masayoshi wasn’t around, since Samurai Flamenco isn’t big on interior monologue.

…well, it didn’t seem like it was.

The revelations in 19 and their fallout therefore don’t just cast new light on a few scenes — they impact virtually every episode, even those in which Gotō has a minimal part. That’s not to say that the impact is the same in every instance, though. Sometimes, knowing what’s in Gotō’s backstory clarifies what was formerly an ambiguous moment, like Gotō agreeing to overlook Samurai Flamenco and Flamenco Girl’s activities despite being tased by Mari the night before. Gotō is pretty forgiving -- but it probably didn't hurt that Masayoshi pointed how Mari’s violent vigilantism “saved many women who might have been victims.” (To drive it home, what does Gotō do as soon as Masayoshi says that? He looks at his phone.)

More often, knowing where the messages Gotō receives are coming from seems to offers new insight into what Gotō is thinking, suggesting inner turmoil not visible on the surface, or intensifying an otherwise understated emotion. (Think of Masayoshi’s sunny acceptance that killing monsters is part of being a hero during Torture Arc, Goto’s obvious unease — and his Girlfriend saying that the look in Masayoshi’s eyes frightens Her.) Occasionally, this can shift the overall tone of a scene. The most memorable instance is, of course, when Gotō gets a message in the middle of trying to Stop the Rocket, turning what was already the best gag in a subtly comic action scene into one of the most wonderfully WTF moments in the entire series. More generally, though, when Her texts trigger a tonal shift, it usually makes the scene in question a little more melancholy, in direct relation to how happy and/or invested in his relationship Gotō appears at the time.

While I won’t discuss the Gotō’s Girlfriend situation in every write-up, I do plan to come back to it often. Beyond cataloging what feels different in hindsight, there's a lot about it that I find interesting and worth exploring — for instance, how to talk about Gotō’s Girlfriend as a character. Even though I generally talk about Her as if She’s singular, She's really two characters who overlap but aren’t identical: Real Girlfriend who disappeared when She and Gotō were in high school; and Text Girlfriend, Gotō’s coping mechanism who exists only in his head and in his texts, but who nevertheless exists as a presence for the audience.

Paradoxically, the latter is the more developed Girlfriend and the one we get to know best, while Real Girlfriend becomes more of a cipher the more we learn about Her. That's worth discussing on its own, I think, AND in connection with everything that happens with Her and to Her in Final Arc. I have such complicated feelings about that that this write-up gets delayed a week every time I try to say more than "I'm going to write about this at length later." Suffice it to say for now that there’s a lot I like and also parts I find troubling, and I can’t wait to dig into it…eventually.

Before moving on to episode-one-specific Girlfriend discussion, a few notes on terminology and approach. First and foremost, I’m going to do my best to discuss Gotō’s mental state in a sensitive way, not just in terms of the language I use, but also how I frame my discussion. Second, because “Text Girlfriend” is the one we spend more time with, you can assume that if I don’t say otherwise, She’s the one I’m referring to when I say “Gotō’s Girlfriend.” Finally, and related to number two, unless it’s genuinely necessary, I’ll avoid going out of my way to flag the difference between Text Girlfriend and Real Girlfriend — for instance, putting big quotes around “Her” to indicate that we’re talking about texts that aren’t from Real Girlfriend (ex. "Then Gotō shows Mari one of 'Her' texts, and..."). That would arguably be a more precise approach, but I’ll be taking a lot of care not to conflate the two Girlfriends — and assuming you took the spoiler warning seriously, you’ve seen the show, and you don’t need me to keep highlighting the obvious.

Getting Acquainted with the Lovebirds ~ヾ(^∇^)

Virtually every scene focusing on Gotō, his Girlfriend, and their relationship become at least a little bittersweet on rewatch, but I think that’s especially true of their bits in episode one. The obvious reason is because for most viewers, this is the first episode you revisit after watching episode 22. You go from seeing Gotō in the depths of despair after losing Her -- and thanks to the flashback, you actually suffer through it with him twice in the same 22 minutes. Then, suddenly, Gotō is back in that relationship, looking happy and satisfied, except now you KNOW. And you know what he's in for 21 episodes later. So that’s part of it.

The other reason these scenes can be painful the second time through is because episode one so effectively sells Gotō’s Girlfriend as a character, along with Gotō’s feelings for Her. Her texts convey a vibrant and distinctive personality — although not all of it comes through in the simulcast translations. For instance, She doesn’t just open that first text with “Hey,” but a more playful “Nyahoho~i”; and says “I want to see you” four separate times, with the last three coming almost one right on top of the other — “I want to see you! I want to see you I want to see you I WANT TO SEE YOU.” There’s also a skipped-over line that has her playing up her embarrassment at having left her umbrella behind (“(/ω\) Embarrassed— 💩”)

I bring this up just to note it, not to rag on the translator(s). Apart from the ordinary stresses of simulcast translation, limited onscreen space, and limited time to display the translation, it wasn’t obvious at this point in the series that Gotō’s Girlfriend’s texts would be important enough to warrant a fuller, more colorful translation. Plus, they did include the \(^O^)/ emoji in their translation of the first message, which draws attention to all the embellishment in the original, thereby giving a little more of the flavor of her messages than we’d get if it were just straight text.

And really, you don’t need to be able to read Japanese to see that Her texts are packed with emoticons and emoji, including animated hearts, surprised and embarrassed faces, and ample use of the poop 💩 emoji. Look a little more closely, and you’ll notice every sentence has something attached to it, acting as intensifiers (the blue despair face 😨, broken heart 💔, and poop 💩) when she announces she can’t find her umbrella), clarifications (the little purple devil 😈 that turns “I’m kidding” into good-natured teasing), and decoration, as when her nickname for Gotō, “Gocchin,” is flanked by six different emoji (“💖🐷 Gocchiiiiiiin✨❤️🦁🌸”). She sometimes substitutes emoji for words, like the umbrella emoji ☂️ for “umbrella,” and also seems to enjoy visual punning: when She announces She’ll come next month to take — “tori” — her umbrella home, She follows that with a bird emoji 🐦, which can also be “tori.” Then She turns “yoroshiku onegaishimasu” into “yoroshiku onegaishimanbooooo,” ending with a mola mola/ocean sunfish emoji, which is “manbo” in Japanese.

Already, a particular voice and presence emerges from these two messages. Gotō’s Girlfriend comes off as cute, playful, and clever, but with a certain agreeable weirdness, too (“onegaishimanboooo”). That She can be informal and joke around with Gotō (“I want to see you” x 4, “Just kidding, I’m going to bed”) suggests She’s confident in a well-established relationship, and that She and Gotō are enough on the same wavelength that She can say something like that without fear of hurting him. Alternately, maybe She’s a little thoughtless about stuff like that. But looking at all the decoration, these are messages that would take a little effort to type out, so we could see that effort as a sign of Her affection — along with the fact that as emoji/emoticon-intensive as Her messages are, She replies almost immediately when Gotō answers Her text about the umbrella.

Gotō’s quick to pick up, too, snapping open his phone just as soon as he gets the notification and staring intensely at the screen as he reads. Then…he just melts. Cut to Gotō walking to the convenience store, humming to himself; he’s swaying side to side, a little spring in his step, a smile on his lips…

His pace starts to pick up; his grin widens.

Now he’s running, now he’s bounding down the street — and finally, unable to contain himself any longer, Gotō lets loose a joyous shout into the night.

Sugita’s performance is perfection — and I think that’s true of Gotō’s portrayal here more generally. We don’t have to be told that Gotō is smitten with his Girlfriend — we can see it in the way that he’s physically overcome by his feelings for Her. That sudden burst of energy is in such stark contrast to the Gotō we saw standing guard at the police box just moments ago, not just visibly bored but frozen in place, literally unmoving until the very end.

Now, to be sure, that scene reads as more comic than bleak, thanks to its bright color palette and the lighthearted background track (“Nonki na Hirusagari”). Still, it’s clear that police work can be dull, and that Gotō’s relationship is a little ray of light that allows him to endure the dullness, and the coming home to a teeny-tiny apartment where no one is waiting for him, and the not being able to go to the convenience store without having to get past a bunch of idiot kids acting like idiots right outside the door,

and of course there’s a huge line, and oh would you just LOOK at this DRUNK ASSHOLE cutting in line, and of course the cashier just rings him up like it’s no problem —

I’m deliberately laying it on a little thick here, because, again, the tone of this segment is light — but because the tone is light, it can be easy to miss that our introduction to Gotō is largely a collection of the little frustrations that are part of Gotō’s daily life. The exception is his time with his Girlfriend. At this point in the series, Gotō’s contentment is entirely wrapped up in Her, and damn that’s painful to type now. I do think it’s to the show’s credit that none of this plays as farce the second time through, especially given how over-the-moon Gotō is. It’s all a little weirder, and I do find myself asking questions like “Is this the first time he’s done the bit with the umbrella, or is this an established scenario he runs through every now and then?” But the overwhelming feeling I have is pity, for him, and for Her.

One last thing episode one-specific thing I’d like to note before wrapping up. As much foreshadowing as Samurai Flamenco offers, the show generally avoids tipping its hand vis-a-vis the Gotō’s Girlfriend situation. I’ve rewatched the show many times, and found just a few instances that, in hindsight, seem like blatant hints that things aren’t exactly what they seem. See, for instance, episode 4: Gotō sends Her a text, and while he’s waiting for a response, he types out another message that we don’t see. The next time he opens his phone, he has a text waiting on him from Her.

Σ(・口・)

Episode one has something that may qualify: in certain shots early in the episode, Gotō has lines under his eyes that aren’t part of his standard character model.

We see them during his first scene at the police box, when he’s so deeply bored, then they show up again when he’s texting his Girlfriend at his apartment after work.

Their final appearance is when Gotō is listening to Masayoshi explain his crimefighting plans, just after the commercial break.

It’s be easy to read that as Gotō just being exhausted…although the only other time I recall seeing Gotō with lines under his eyes like this with any consistency — and he isn’t just waking up or something along those lines — is the long flashback in episode 22, when Gotō is drowning in grief over his Girlfriend’s disappearance.

In that light, this feels kind of like a sign: “Despite seeming like a fully functional adult in a wholly satisfying relationship, Gotō is still suffering, maybe more than he even knows.” In general, I think that’s true, especially given how Gotō reacts to Masayoshi calling him out in episode 20 — but I’m hesitant to put a lot of weight on these lines as evidence given that they sort of…appear and disappear. They’re completely gone after Gotō leaves his apartment for the convenience store, and stay gone until after the episode’s midpoint. Then, after their brief appearance in Masayoshi’s collection room, that it — lines no more. It’s not simply a matter of omitting details that wouldn’t be visible from a distance, either — we get plenty of close-ups between the convenience store and the collection room, and no lines. If the show wanted Gotō with lines under his eyes to mean something really important, you’d expect them to be consistent, right?

At the same time…you’ve seen Samurai Flamenco, right? This show struggled to stay on model for features the characters are supposed to have all the time, like Masayoshi's prominent lower eyelashes. It wouldn’t be surprising for a design element that was only supposed to be in place for part of an episode to go missing during the initial broadcast run. And as much attention to detail as the Blu-ray improvements show, corrections were relatively skimpy until the Flamengers arc. So I do think it’s plausible that the show may have intended the lines under Gotō’s eyes to carry a specific meaning that would become more apparent on second viewing — and they just dropped the ball. We'll probably never know, though.

Broadcast vs. Blu-Ray - Are the Improvements to the Blu-Ray version of This Episode Enough to Justify Seeking it Out?

Yes, but I’d say more if you want to get a friend into Samurai Flamenco than if you’re interested in a dramatically different viewing experience. The broadcast version of “Samurai Flamenco Debut!!” wasn’t particularly polished despite being the first episode out of the gate, and the alterations made for the home video release are relatively minimal. If you’ve seen the show already, you probably won’t notice them the way you will the revisions to the Flamengers episodes, for example.

That said, there are some changes that I appreciated. The first part of Masayoshi’s “CHANGE! SUNSHINE!” gets an animation bump, adding details to each frame. More importantly, there are also small fixes that improve spatial continuity, like replacing the background behind the drunken salaryman during his confrontation with Masayoshi so that he actually drops his cigarettes in the street Gotō ends up walking down. That wasn't true of the broadcast version. Likewise, the Blu-ray version makes sure that the video of Masayoshi lecturing the delinquent middle schoolers shows him pointing a finger at the delinquent middle schooler recording him rather than randomly thrusting his finger into the sky. It’s a better-looking episode, no question, but the difference isn’t dramatic.

See my detailed comparison here.

Scattered Observations

“Samurai Flamenco Debut!!” is the only episode for which series director Ōmori Takahiro provided the storyboards, and one of only two for which he serves as the episode director. (Would you be surprised if I told you the other was…episode 22?) This is fairly typical for Ōmori, who is often credited as the “director” or “chief director” for a series as a whole, but “episode director” for only the first and/or final episode of a show. I have a pet theory that in addition to what we generally think of as directorial skills (knowing how to set up a shot to create a particular impression, coaching performances, etc.), Ōmori is also a talented project manager, and that he’s a big part of the reason why Samurai Flamenco came out as good as it did as studio Manglobe approached its end.

The setting of Samurai Flamenco is Yukimachi Town, a (fictional) district within the larger (equally fictional) Shibiru City. We aren’t actually in Tokyo proper yet, and won’t be spending a lot of time there until the Flamengers Arc.

You may have noticed that Gotō and his co-worker Totsuka sometimes have a dark-colored stab vest on over their uniform, but usually only one of them at a time. That’s not an error — if you watch, it’s always the one who is standing guard outside the police box, or who has just come from in from doing so. That specific duty is called ritsuban. The fact that the one standing outside is usually turned away from the police box interior makes it easy for Gotō to conceal his reactions when something Samurai Flamenco-related comes up. Likewise, that Totsuka is looking inside during Masayoshi and Gotō’s conversation in this episode underscores that yes, Totsuka is listening in…

Every character seen in the opening has at least a cameo in episode one, although Mari, Mizuki, and Moe only show up on a magazine cover. They won’t appear in person until episode two.

Look closely when Masayoshi opens the door to his apartment, and you’ll see he has a Red Axe keychain.

The curry Masayoshi and Gotō eat is branded with Brass Rangers Ensemble, the sentai series that’s airing in-universe during this part of Samurai Flamenco’s run, and that Masayoshi has a guest spot on in episode 5.

If you enjoyed this write-up, please share it with your friends, and support Samurai Flamenco in whatever way possible. Stream from legal sources (ex. Crunchyroll), buy the home video releases if they are available where you are (I can personally vouch for All the Anime’s excellent Region B Blu-rays, and am currently enjoying Peppermint Anime's German dub), and support people who engage with the show, whether through critical essays and appreciations, fan art and fan fiction, remixes, or whatever.

Until next time, FLAMWENCO!

Ko (ratherboogie)

#samurai flamenco#samumenco#hazama masayoshi#goto hidenori#goto's girlfriend#gotou hidenori#long post#image heavy#gotou's girlfriend#samumencometa

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Samurai Flamenco, In Hindsight” 5th Anniversary Recap Project - Introduction

October 10-11, 2018 will mark the fifth anniversary of Samurai Flamenco, an oddball original series produced by studio Manglobe for the back half of the Fall 2013 noitaminA block on Fuji TV. The show’s 22 episodes aired alongside a lot of other series that I still look back on fondly, but nothing else from that period hit me as hard, or has stuck with me as long. Samurai Flamenco pushed me to do things I hadn’t done in years, like leaving the fandom sidelines to discuss the show with total strangers instead of lurking on the edges of others’ conversations, and exploring the show’s characters, story, and themes through art and writing. Eventually, I even started watching some of the tokusatsu shows the series is so interested in so that I’d have a little more context (and could get more of the in-jokes). The show has gotten me through some hard times, as have the friends I’ve made through the small but devoted SamFlam fandom.

I love Samurai Flamenco, and I love what engaging with Samurai Flamenco has brought to my life. And so, to celebrate the show’s fifth anniversary, I’m planning to spend at least the next year doing extensive write-ups on all 22 episodes. These won't be reviews, but more like essays, each focusing on whatever struck me most about the episode in question. For instance, I'll be looking at the use of repetition in the premiere episode, "Samurai Flamenco, Debut!", while episode 2's write-up will talk about how "My Umbrella is Missing" develops (and complicates) Masayoshi as a character. Episode 3, I'm thinking I might talk about how “Flamenco Versus Fake Flamenco” sets up the series' overall look at violence as it relates to heroism and hero media…but I haven’t re-watched the episode for this project yet, and I want to be open to whatever this particular viewing suggests would be most interesting to talk about.

More details below the cut!

That might sound like a haphazard approach, but attention to each episode as its own distinct thing is one of my guiding principles for this project. An episode of a television show is always part of a larger whole, but it also remains singular, and looking at an episode on its own can be just as worthwhile as taking the opposite tack. I think that's true even for super-formulaic whatever-of-the-week series — but that it's especially true for a show like Samurai Flamenco that plays with so many genres and sub-genres, isn't afraid of big tonal swings, and will very explicitly race through an entire season’s worth of monster-of-the-week fights in a single episode to make points about toku TV and hero media more generally. I will never be able to talk about everything I find interesting about this show, but this approach should at least give me plenty of opportunities to discuss plenty of different topics. (That said, of course I’ll be drawing connections between episodes and across the series as a whole, because why else do a retrospective project? I picked that subtitle very deliberately!)

More on What to Expect

Every write-up will begin with a short episode summary, and wrap up with some stray observations. You can probably also assume that each of these will include some amount of close formal analysis — that is, taking apart what we actually see onscreen, what we hear, and how it all unfolds in time — as a way of understanding how the show works. Episode one’s write-up is largely that; episode two is significantly less so, but you can still expect a fair amount of “long shot” this, “low angle” that, “shot/reverse-shot” SIT DOWN, and so on. I’m taking that approach in part because while I recognize the very real limitations of formal analysis, I think it can be a good starting point for understanding why something works on you as a viewer — or why it leaves you cold, uncertain, etc. (I also just enjoy doing formal analysis; it’s fun for me, and this project is meant to be a little self-indulgent.)

But I’ll also lean toward formal analysis because I think Samurai Flamenco generally doesn’t get enough credit for how well put-together it is. I know, I know — the art is often off model; the animation isn’t particularly impressive; have you ever noticed how unfinished the backgrounds were in the broadcast version of episode 14, holy hell. And the MUSIC, don’t get me started on

...well, to be honest, I’ve got a soft spot for the soundtrack, and think it fits the show’s overall tone and aesthetic fairly well. So no real complaints there from me there — but I do get it.

Still, having watched Samurai Flamenco start to finish more times than I can count, single-framed my way through both the broadcast and Blu-ray versions of the show, and futzed around on a defense of the much-maligned Flamengers arc longer than I care to admit, I’ve spent a fair chunk of time looking at this show up close. There is a lot of rough stuff, yes, but also a lot of really solid visual storytelling, great attention to detail, and some very daring choices, particularly in terms of what’s left up to the viewer to figure out on their own. The show has good bones, I think, sometimes hidden by wobbly execution. Beyond that, I think Samurai Flamenco’s story structure is ridiculously good — that as much as we talk about the WILD RIDE and MULTI-TRACK DRIFTING*, in hindsight, the show is carefully set up to go all the places it does in a fairly well-paced way, enabling the character development to unfold realistically over time, and very little feels rushed that doesn’t feel like it was meant to feel rushed.

All this is a long way of saying that I think there’s a lot of good in Samurai Flamenco’s construction that I want to highlight, and sometimes that will require going shot-by-shot to explain what I mean. I’ll try to keep the jargon to a minimum, though — and for long segments, I’ll provide time codes if you want to see if your read checks with mine.

A final content note: be forewarned that all of the write-ups will assume you’ve already completed Samurai Flamenco, meaning they will be FULL OF SPOILERS FOR THE ENTIRE SERIES.

Posting Schedule

(or, You Never Know What Could Happen to You in the Final Episode, But I Do Know It’ll Take a While to Get There...)

My original plan was to post each episode’s write-up on the anniversary of its original airing, working out to one a week for approximately 22 weeks. Then I started work on episode 1, and…well, maybe I’ll pick up speed as I go, but one a week was way too optimistic given the time I actually have to work on these, and how slowly I write. So these write-ups will come out as I have them ready. If that’s one a month or every six weeks, so be it — but I am committed to finishing this project.

A final programming note: I’m starting this project here on tumblr because, frankly, I need to start, and this is what’s easy and available at the moment. At some point, I may migrate to a blog. If I do, I’ll continue to announce new write-ups here and then link to the complete post, so if you’d like to keep tabs on this project, follow this tumblr for updates.

Closing

I hope that you’ll enjoy reading these write-ups at least as much as I enjoy writing them. If you do, please share them with your friends, and support Samurai Flamenco in whatever way possible. Stream from legal sources (ex. Crunchyroll), buy the home video releases if they are available where you are (I can personally vouch for All the Anime’s excellent Region B Blu-rays), and support people who engage with the show, whether through critical essays and appreciations, fan art and fan fiction, remixes, or whatever.

Until next time, FLAMWENCO!

Ko (ratherboogie)

* When a show that should be a “train wreck” avoids careening off the rails and instead becomes even more entertaining, not by fixing what’s “wrong” with it by conventional standards, but by continuing to do its own thing with confidence, commitment, and a sense of purpose. It’s not an entirely positive label, carrying a whiff of “I know this is trash, but...” Still, you don’t say a show is MULTI-TRACK DRIFTING if you don’t love it -- and if you continue to enjoy Samurai Flamenco after episode 7, you know immediately why it gets this label.

(For full context, look up the Initial D parody “Densha de D.”)

27 notes

·

View notes