Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Violence Against Women as a health policy issue: The missing agenda

A systems analysis of structural and cultural factors that maintained violence against women in India led to the conclusion that violence against women is perpetuated through social norms and maintained through a process of socialization that normalizes women facing violence. Even when women are educated, they are married to men who are less educated, leading to them facing violence in their personal relationships, displaying how society in India normalizes gender-based-violence and the deep-rooted nature of patriarchy. For women who face violence escaping it is a grueling process that cannot be undertaken without support from other systems such as governments, legislation and policies. Gender relations are essential to consider when it comes to the development of policies purely from a human rights perspective. Unstable and unequal gender relations in countries can lead to negative effects on the economy and productivity of society. The aim of this paper is to assess the National Health Policy of Bangladesh primarily with some discussion about India with regards to violence against women. The paper evaluates whether or not domestic violence is considered a health issue in the respective countries’ policies and presents evidence of why integrating domestic violence into the health agenda of a country is crucial. The reason for drawing attention to Bangladesh and India are because of the similarities in culture as they were historically one country. Secondly the fact that these injustices continue to exist even with female leadership are crucial to assess.

The paper first defines Gender Based Violence and outlines a brief history on conventions that led to the current consensus on women’s rights. It secondly assesses the physical and mental impacts of abuse. Thirdly it evaluates Bangladesh and the gaps in their Health Policies when addressing Violence Against Women. Fourthly, it briefly focuses on India’s Health Policy. Lastly it concludes with emphasizing why gender-based violence is a health concern that needs integration into health policies.

Gender Based violence includes any form of violence or harmful behaviour that is inflicted upon another due to their sex. It includes but is not limited to rape, marital rape, sexual abuse, dowry death, sati, selective malnourishment etc. (Heise et al, 1166).

Changes when it comes to Women’s rights started in 1975 in Mexico City where the First World Conference on Women was held. The health issues of women in third world countries influenced the development and vision of the Millennium Developmental Goals in the 1990’s. In Beijing, 1995, the definition of The Convention of the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) was expanded to include “violation of the rights of women in situation of armed conflict, including systematic rape, sexual slavery and forced pregnancy…” (Mahapatro, 184).

Domestic violence is one of the most prevalent and endemic forms of violence sustained by women in developing countries. The violence endured extends beyond just physical abuse. Psychological and mental abuse as a result of physical violence cannot be ignored(Heise et al, 1166). In Bangladesh and India, domestic violence is one of the leading causes of female deaths and suicides, highlighting the gravity of impact violence has on health. Psychological and somatic side effects frequently include chronic headaches, eating disorders, depression, muscle aches, vaginal infections and sleeping disorders (Heise et al, 1167). Research suggests that domestic violence can lead to long term negative health detriments such as hypertension and heart disease. Violence against women is now recognized by the United Nations as a “fundamental abuse of women’s human rights” (Heise et al, 1168). In developing countries, whether or not violence against women is considered urgent depends on whether it is interpreted as a crisis. This is one of the key areas where issues arise as in these countries it is considered a matter of ‘low politics’ and a private issue that should not be dealt with in the public sphere (Heise et al, 1168).

In Bangladesh and in India after the UN’s declaration of the Decade of Women (1976-85), the respective governments undertook programs to advance the rights of women. After the women’s conference in Beijing emphasis was placed on including Violence Against Women as a health concern by NGO’s and the governments. However, these remained unaddressed at a health policy level (Deosthali-Bhate et al, 8).

In Bangladesh, the National Health Policy did not include violence against women or address domestic violence. In recent years, there have been the development of one stop crisis centres however these efforts have largely been coordinated by NGO’S. There is a lack of concrete government policies to address domestic violence as a health issue complied with a lack of legislation and laws protecting women against it. While at a global and international level there has been an inclusion of women’s violence as a health concern, at a national policy level this remains an agenda to be addressed. Undertaking a life-history approach to domestic violence in Bangladesh, revealed that 72% of women are beaten or abused by their husbands at some point in their lives. Most incidences of abuse are sustained at a family level (Kaosar, et al,3).

The National Health policy of Bangladesh is yet to be publicised. Health sector reforms in terms of policies so far include the Health and Population Sectoral Program (HPSP) and the Health, Nutrition and Population Sectoral Program (HNPSP). However, domestic violence as a health issue is still not prioritized. An emphasis on State and NGO’s to address violence was initiated in 1997 when the government declared the National Policy for Development of Women under the ministry of Women and Child Affairs. The main aim of this policy was to focus on developing women as a human resource, providing them more opportunities in the economic sphere and eliminating discrimination against women and girls. Policies addressing women’s violence and it’s impact on health are “not straightforwardly articulated in Bangladesh” (Kaosar, et al,5). The National Health policy, which has been under the process of drafting and amending for two decades fails to recognize the issue of gender-based violence. While the HPSP recognized GBV as a public health concern and recommended the need for more sensitive public health facilities and gender sensitive training for personnel – the designing of a program to implement this was not put into practice.

Another initiative to battle violence against women as a health concern was the Women Friendly Hospital Initiative that offered gender sensitizing training to hospital personnel. However, the initiatives working to combat these issues are slow paced and combated by cultural and social issues such as “individual experiences, commitment and attitudes” (Kaosar, et al,6). that impede the process. For instance, women who are victims face barriers in seeking medical certificates which are mandatory when seeking legal counsel. There is a lack of female doctors at health centres and male doctors are reluctant to help women. Male doctors who treat women are “reluctant to give certificates immediately for rape cases” (Kaosar, et al, 13) due to a lack of training and a bias in attitude that stems from social norms. Their attitudes often result in victim blaming and questioning the character of women seeking help. Doctors often humiliate and add to more trauma by “openly doubting whether the female was ‘really’ raped, or it was consensual sex” (Kaosar, et al, 13). The health services available to victims of such crimes are thus inadequate and inaccessible. In the absences of adequate laws and policies, informal punishments are administered by the police if a wife can prove that she was subjected to abuse. The husband pays a fine of approximately “Taka 300 -500 (US $5-8) to his wife” (Kaosar, et al,6)

The main concern that is raised is the lack of willingness and political commitment of the state to implement laws and policies. The main strategies used by the policy community to stop GBV have been publicizing cases, legal awareness and lending health and legal aid to victims. The plans of the Bangladeshi government to address this issue have been underway since 1985 with the National Development Plans that aimed to increase female participation in the economic sector by implementing bottom up planning. The Ministry of Women and Child Affairs offers shelter homes, legal and health aid to victims. There are many organizations working to prevent abuse against women using advocacy as a means to influence policy and bring about change. The problem lays in the fact that advocates are given a seat at the table only to a certain extent. This minimizes involvement of women and advocates in the policy making process. For example, public consultation was involved when it came to the creation of the HPSP and HNPSP however “the structure of policy and implementation was formulated by the government officials”(Kaosar, et al,9). Thus, while advocates are able to bring the issues women face to the forefront, they remain invisible in the process of policy formation leading to a lack of pro women policies.

Hence in Bangladesh the main concerns regarding the national health policy is firstly it’s failure to recognize domestic violence as a health concern even when scientific evidence suggests it has detrimental impacts to health. Secondly due to a lack of representation when it comes to policy making, domestic violence is a missing agenda as it is not understood by policy makers as to why it should be under the domain of a health policy. Due to a lack of recognition of domestic violence as a health concern there are gaps in the health sector and care that is provided to victims. Health infrastructures to deal with abuse are inadequate at a grassroots level and doctors and nurses are not trained or given responsibility to handle such cases at “primary, secondary or tertiary levels” (Kaosar, et al,10). While there are operating one stop crisis centres since 2001 these have only been implemented in 2 tertiary hospitals leading to a lack of access and decreased effectiveness. For a population of approximately 140 million people, only 2 centres leave many vulnerable without access to help. Medical colleges and hospitals are equipped to examine women however hospitals do not document these cases properly making it harder to get legal assistance. Government run health facilities face issues such as understaffing and shortage of drugs due to a lack of resources and adequate budgeting.

Hence the example of Bangladesh highlights how there is a lack of policies surrounding domestic violence as a health concern. The lack of policies leads to a lack of appropriate measures to deal with domestic and gender-based abuse.

In India, a similar problem is faced by victims of domestic violence. India’s National Family and Health survey finds that one in three married women face domestic violence. In India there is legislation such as The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act that came into force in 2005 which aims at protecting women in abusive domestic relationships. India is also a signatory to “human rights conventions such as the International covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and Convention on Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against women” (Deosthali-Bhate et al,8) . This places immense responsibility on the government to deal with and protect women against abuse. However, despite there being legislation on these fronts and India internationally recognizing domestic abuse as a health concern – there is lack of clear policy in for the health sector that aids the remedy of such issues. This lack of policy arises partly from limited technical and financial resources for the health sector that inhibit implementation (Deosthali-Bhate et al, 8). Furthermore, there is a lack of training for nurses and doctors to deal with victims of such abuse. In 2013, the WHO recommended that “health systems responses to VAW be integrated within clinical care at all levels” (Deosthali-Bhate et al, 10). The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare failed to translate these recommendations into policy guidelines. It was only after the brutal rape of a young doctor in New Delhi in 2012 that led to a public outcry and protests that led to the Ministry developing medico-legal guidelines for survivors of sexual violence in 2014 (Deosthali-Bhate et al, 10). Only in 2017 did India’s National Health policy recognize violence against women as a health concern. The policy now mandates free medical and legal services to all survivors of sexual abuse.

The influence violence has on a woman mentally and physically clearly highlights how intertwined violence and health are. The two cannot be separated. Protecting against violence, having an effective response strategy and considering it worthy enough to be health issues are crucial for developing nations to realize. The fact that violence against women is a missing agenda in health policies itself is a reflection of the work that is left to be done. Women need to be involved in the policy making process but what is more important is ensuring the implementation of the policies to turn their promises into reality.

Works Cited

“Domestic Violence And Health Care In India: Policy And Practice by Meerambika Mahapatro / 2018 / English / PDF.” Only Books, onlybooks.org/domestic-violence-and-health-care-in-india-policy-and-practice.

“Ministry of Women & Child Development: GoI.” Ministry of Women & Child Development | GoI, wcd.nic.in/policie.

“Violence against Women: an Urgent Public Health Priority.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 4 Mar. 2011, www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/1/10-085217/en/.

Afsana, Kaosar, et al. "Challenges and gaps in addressing domestic violence in Health Policy of Bangladesh." BRAC, Bangladesh (2005).

Bahri, Charu. "Gaps in India's health response to violence against women." Lancet 387.10038 (2016): 2591-2592.

Deosthali-Bhate, Padma, et al. "INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN INDIA."

Heise, Lori L., et al. "Violence against women: a neglected public health issue in less developed countries." Social science & medicine 39.9 (1994): 1165-1179.

Sharma, Prachi, M. K. Unnikrishnan, and Abhishek Sharma. "Sexual violence in India: addressing gaps between policy and implementation." Health policy and planning 30.5 (2015): 656-659.

0 notes

Text

Structural and Cultural factors contributing to the maintenance of Violence against women in India: A structural systems analysis

Women have historically been considered inferior to men throughout India’s history. Even though Indians have goddesses they worship, place their ‘mother’s’ on a pedestal and even call their own country ‘Mother India’, women are continually treated with disregard and as secondary citizens. As such, in charting the trends of violence against women, there is an evidently upward trajectory.

The aim of this paper is to firstly analyze and evaluate what factors contribute to a culture of violence against women, and secondly to review why this violence persists regardless of time. The paper combines various levels of analysis - historical, cultural, social and religious - to explain how a culture of violence against women emerged. Additionally, it explores how those ideologies continue to sustain themselves today through socialization and cultural norms.

This paper, therefore, addresses the question: What structural and cultural factors contribute to the persistence and maintenance of violence against women in India?

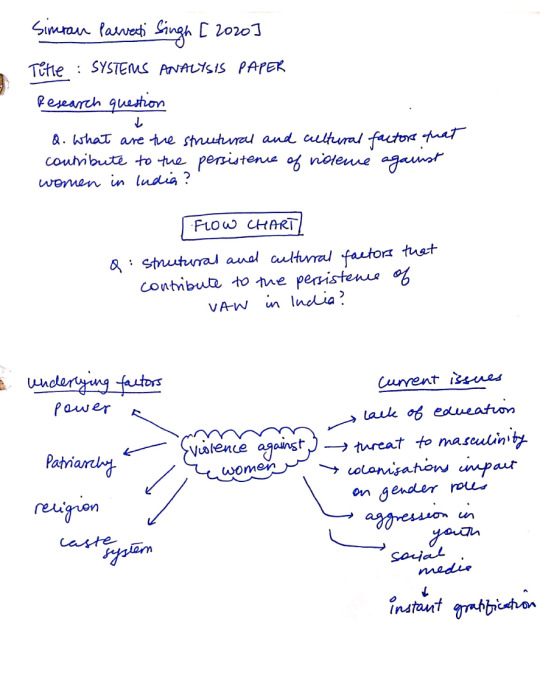

The flow chart below (Image 1) highlights and separates the various factors that interact with and influence violence against women. Culture and structural factors were chosen given their interaction and influence with all other factors. It was believed their analysis would provide a nuanced understanding into why violence persists even in the 21st century.

Image 1: Flow chart of structural factors influencing violence against women in India

The paper is organized in the following manner. First, it defines violence against women, articulating what types of manipulation and violence fall under its purview. Second, it will analyse the historical background from Pre-Vedic times until the British rule, depicting how influences such as religion and systems of oppression have amalgamated to place women below men. Third, it will look at the paradoxical case of Kerala, a state which despite high levels of education and literacy - considered protective factors against violence, continues to have the highest rates of suicide and domestic violence in India. Lastly, it will conclude by examining what factors have maintained and sustained this culture.

Definition and Historical Background

Gender-based violence can be defined as any act - sexual, physical or emotional - that “operate[s] at the intimate, interpersonal to the societal, macro-structural levels.” (Kirmani, 170).

In order to understand the persistence of violence against women holistically, one must understand the history of how and why this culture transpired, alongside the systems that maintain it which will be explored in this section.

Through an analysis of different systems of hierarchies, particularly the caste system in India, Sociologist Fernand Dumon defined it as a system of categorization inspired by religion that propagated the idea of superiority of the pure over the impure (Livnie, 3). Dumont argued that the essence of the Indian caste system relied on principles of oppression and separation of the pure and impure, concepts deeply ingrained in Hinduism, a religion centred around ideas of purity and pollution (Livnie, 3). He posited that this system of separation is ideologically inseparable in Indian society, arguing that although it may change forms, it will continue to manifest itself through constructs such as racism and patriarchy. While this system has been deemed unconstitutional, its impacts have prevailed. For example, despite it now being illegal to characterize individuals as "untouchables", the associated connotations and stigmas this caste carried remain ingrained in modern culture. Even though legally they are seen as equal, people associated with this caste are still considered impure. Such examples emphasize the role culture and societal norms play in the perpetuation of systems of oppression. As such, this narrative can be applied to the system of patriarchy in India, which, at its base, assigns women as subordinates to men. Ultimately, notions of purity in relation to gender have become normalized and hence the marginalization of women continues to be a trend (Livnie, 4).

During the Pre-Vedic period (1500-800 BCE), there were no legitimate gender hierarchies or violence against women. Infact, the contrary was the norm - Women were honoured and worshipped. Their consideration as sacred in Hindu culture is evident in the fact that Hinduism’s gods and goddesses were considered equally powerful and sacred. However, with the establishment of the institution of marriage during this time, these ideals started to change. Women were expected and obligated to stay inside the confines of their households and give birth to a son. As such, despite remaining worshipped, women were now considered objects whose value was defined by the standards established by their husbands and families (Livnie, 4).

Subsequently, the Post Vedic period brought the tradition of Sati, a “Hindu funeral ritual in which a widow commits suicide by way of lighting herself on fire” (Livne 5).

The British colonial period brought Victorian values which stigmatized sexual liberalism in India. Since then, Indian culture has been marked by conservatism, with sex viewed as a taboo. Furthermore, during this period women became representatives of Indian culture and spirituality, with sentiments of nationalism flaring high (Livnie, 5). This, in turn, resulted in women being kept at home as a means of protection against foreign influence. Such effects of colonization have impacted gender ideals beyond India and can be seen across Asia. In Indonesia, for example, there was gender equality prior to colonization. Qualities such as compassion, sharing and cooperation were ideal in a man, however, colonizers deemed these to be inferior, feminine qualities (Prianti, 701). Whereas Indonesia was a collectivist society, where the group needs were placed prior to individual. Western society viewed masculinity as superior. Masculinity was to be understood as men's needs to express their superiority and distinguish themselves from those lacking these qualities. In other words, as a concept to conquer and silence “others' ' - i.e. the other being the colonized subjects (Prianti, 701). During colonization, indigenous populations learnt the hierarchical structure between western notions of masculinity and femininity. As a result, Indonesian men were conditioned to desire the masculine qualities presented by the colonizers as the only way to claim full citizenship (Prianti, 716). India witnessed a similar process, with its already existing bifurcation and gender inequality exacerbated through colonization. It was advantageous for the colonizers to divide and rule, and these impacts remain sustained even today.

Patriarchy, a system wherein men are considered superior to women, emerged with religion and the caste system as a perpetrator (Livnie, 8). However, it was furthered by colonial agenda as a means of division that has been widely normalized in Indian society. Today, Indian culture expects women to be chaste and obedient, ideals rationalized and tolerated through socialization. In fact, Livne found 41% of women held the belief that a man was justified in beating his wife if she disobeyed him or displayed disrespect (Livne, 8). Likewise, these social norms are sustained by the law. For instance, safety is referenced in relation to women taking measures, such as dressing conservatively or travelling with male escorts. In other words, by placing focus on the sexual wrong of men to protect ‘good’ women. In essence, “the campaign about violence against women is dominated by a patriarchal understanding of safety and violence” (Livne, 9).

Furthermore, patriarchy has led to a declining sex ratio, with female feticide on the rise. The intersection of oppressive systems such as patriarchy, the caste system and class hierarchies work together to reinforce male superiority. This interaction is evidently present in the dowry system, the ritual wherein the bride’s family provides cash or goods to the groom’s family for accepting their daughter. Even though the 1961 Dowry Prohibition Act made this practice illegal, it remains significantly present in India. As such, given that having a girl child is seen as a financial drain whereas a male child is seen as a financial gain, female foeticide is furthered. Dowry has also led to an increase in Gender-Based Violence given that when it is considered unsatisfactory, the impact is taken out violently on women (Livnie,11). Such disputes result in the death of 25,000 women being killed between the ages of 15 to 24 every year (Livnie, 12). Nevertheless, its religious significance means it continues to be practised. This violence is tolerated as being unwed or getting divorced is highly stigmatized and a woman’s lack of education and financial dependence forces them to remain in abusive relationships as a means of survival.

Case study of Kerala

Kerala, a state in Southern India, has the highest gender development Index in the country. However, despite high literacy and female educational achievement rates, Kerala is also the state with the highest rates of suicide and domestic violence (Mitra et al.,1228). Researchers Arpana Mitra and Pooja Singh conducted a study to analyze the demographic, social and cultural changes that are leading to the maintenance of this Paradox in Kerala. They found that with an increase in women’s education there was also an increase in their aspirations. Human capital theory posits that educational and literacy attainment are crucial tools for achieving gender empowerment (Mitra et al., 1228). While women in Kerala have achieved this, society still expects them to be subservient. This imbalance between expectations and reality contributes to family violence and suicide (Mitra et al., 1240). Women in Kerala are married off to men who, despite being less educated than them, earn more money, due to labour market discrepancies. The less educated migrant males are more conservative and continue to internalize patriarchal values. This asymmetry often contributes to violence, with the leading cause of domestic abuse being disobedience from the wife. Regardless of being aware of the rights they deserve, demanding them is considered disobedience, which in turn results in additional violence. Furthermore, the dependence on their husbands for financial sustenance keeps women in these marriages, continuing the unequal power relations and cycle of abuse. Ultimately, Mitra and Singh’s research concluded that much of the violence inflicted is a result of defiance and resistance from women to traditional norms that patriarchal systems dictate. An awareness of their rights and vocalization of such is viewed as defiant, hence there continues to be an increase in Gender-Based Violence. Relative resource theory suggests that there is an inverse relationship between men’s’ economic resources and instances of violence against women (Kirmani, 172). A study conducted in Pakistan found that in certain instances, domestic violence experienced at home has increased due to an increase in women’s economic activity. This implies that, especially in cultures where men are expected to be the family’s breadwinners, as women earn more than their husbands, men often respond with violence in order to assert their patriarchal authority. Furthermore, market forces produce and sustain gender inequality by continuously underpaying and under employing women (Kirmani, 172). While there isn’t a direct link between employment and the rate of domestic violence, women’s participation in the workforce comes at a cost. While working may give some women the ability and resources to leave abusive marriages, most don’t because of to the social stigma attached to divorce (Kirmani, 182). Similarly, paid work also leads to an increase in household tensions as women are expected to fulfil their domestic roles which increase stress and conflict.

While women are being given more liberties and their education is supported by the image of the ‘new woman’, the direction of change is circumscribed by classed and gender practices of respectability, with the ‘choices’ girls, have still being dictated by cultural authorisation. Society and parents of girls continue to stay deeply committed to certain forms of femininity (Hussain,165). Hence, women are ultimately discouraged from seeking economic independence and freedom by society. Even if they do, the independence they reach is dictated by a patriarchal society.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while there are changes in the way women are being treated and the opportunities they are now presented with, these are still dictated and controlled by systems of gender that support patriarchy. It is considered a privilege for a woman to be ‘allowed’ to work or get an education, while for a man it is a given. The main cause for the persistence of these inequalities is the cultural acceptance and normalization of men using violence as a means of conflict resolution. Hence, until cultural and societal changes accompany educational and labour market reforms, ending a culture of inequality and violence against women is not truly attainable. There must be a simultaneous change at both levels to ensure the end of gender inequality. For women and men to be equal, women must be seen as equals and intellectual and financial necessities must stop being viewed a privilege ‘given’ to women (WHO, 7). Economic engagement and education can only lead to empowerment if there is a simultaneous transformation in gender relations at the structural household and cultural level.

Works Cited

Hussain, Saba M. "Merging Career and Marital Aspirations: Emerging Discourse of ‘New Girlhood’Among Muslims in Assam." Rethinking New Womanhood. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018. 147-168.

Kirmani, Nida. "Earning as Empowerment?: The Relationship Between Paid Work and Domestic Violence in Lyari, Karachi." Rethinking New Womanhood. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018. 169-187.

Livne, Emma. "Violence Against Women in India: Origins, Perpetuation and Reform." (2015).

Mitra, Aparna, and Pooja Singh. "Human capital attainment and gender empowerment: The Kerala paradox." Social Science Quarterly 88.5 (2007): 1227-1242.

Prianti, Desi Dwi. "The Identity Politics of Masculinity as a Colonial Legacy." Journal of Intercultural Studies 40.6 (2019): 700-719.

World Health Organization. "Changing cultural and social norms that support violence." (2009).

3 notes

·

View notes