good omens side account s2 scrambled my brain, physically can't think about anything else contains untagged spoilers

Last active 60 minutes ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I’ve extended my sh0p’s summer sale because now there are some 11”x14” comic posters available! If you’ve ever wanted to put some of my comics on your wall, now is your chance!

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

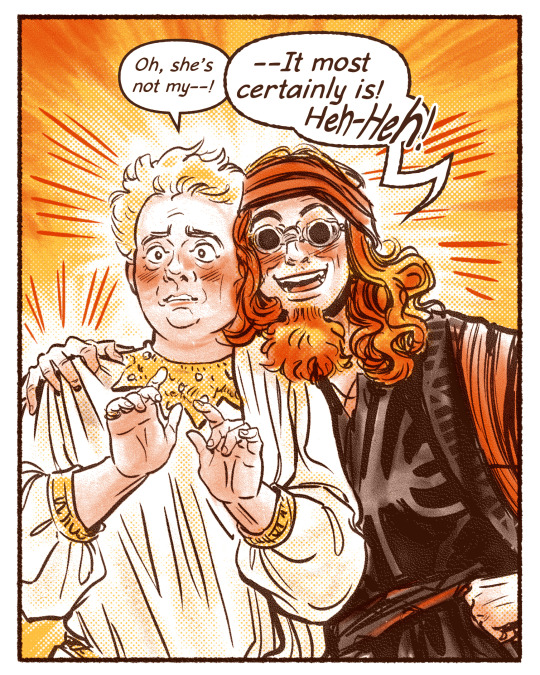

I cooked 3 pages of Beardy!Butch Crawley/Ostensibly Femme!Aziraphale goodness for @bildadzine of which you have just a couple more days to grab a copy of. Proceeds go to RAINN and Safeline!

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

The man that I love sat me down last night And he told me that it's over, dumb decision

And I don't wanna feel how my heart is rippin' In fact, I don't wanna feel, so I stick to sippin' And I'm out on the town with a simple mission

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

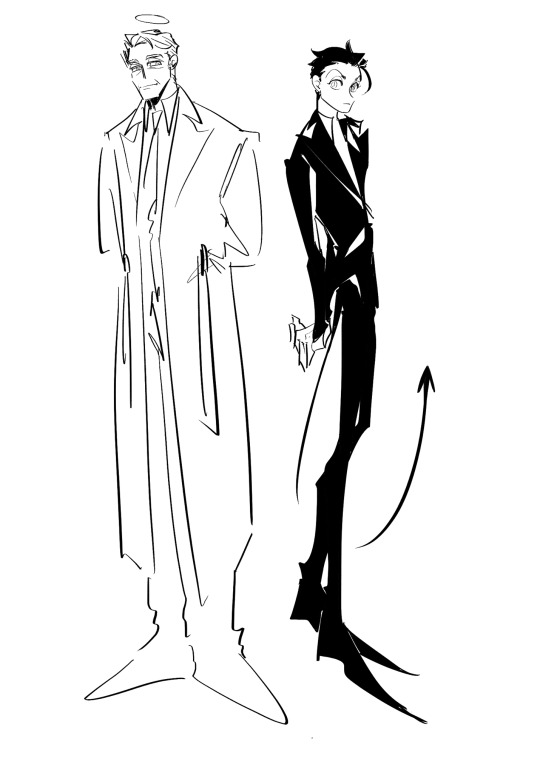

well, heaven knows

that without you is how i disappear

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

book aziraphale and crowley look like young adults while having the relationship of an elderly couple celebrating their golden anniversary meanwhile show aziraphale and crowley look middle aged while having the relationship of dramatic teenagers. do u see.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Disability will have you thinking shit like “I’m not even that disabled. I can manage as long as I limit myself to very specific careers, never go shopping for more than an hour or two at a time, keep my plans open so I can cancel and stay in if need be, and only go out a few nights per week at the most”

#mmmmm#“i do not deserve disability benefits because i'm not that disabled”#<- guy who has not left the house in weeks#last time i was able to go to a social occasion was 6 months ago#everything is fine

79K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cranking up celestial spheres with a starting handle (which Crowley later uses for his Bentley) is actually a very accurate detail. That's how angelic mechanics works, at least according to medieval manuscripts :)

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

lover boy 💓

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

100% agree, Crowley is not a radical by human standards. He may be viewed that way by the other celestial beings, but that isn't the same thing. At least before the end of S1, none of the others seem willing to even consider whether the system could be less than completely justified and inescapable. By comparison almost anything would appear extreme.

Actually, from the way it's been discussed so far it doesn't seem like Crowley was a real revolutionary even when a large number of other soon-to-be-demons were mid-rebellion. He may have been an angel who asked questions, but when he realized the answers were terrible or nonexistent, his only priority seems to have been finding a way to be comfortable living with that. His fall was about "hanging around the wrong people," not openly defying the powers that be or working towards fixing things (outside of quietly gaming the system for his own benefit, anyway.)

There's always the possibility of a reveal that Crowley was involved in more active resistance as an angel than what he's let on so far, but that would only provide a reason why he's convinced there's no point trying to fix anything systemic (if he failed with half of Heaven on his side, what chance do he and Aziraphale have on their own?). Better understanding of his reasoning doesn't change the reality that, at least since becoming a demon, he has embraced the status quo as long as he can mostly keep doing what he likes.

None of this is meant as Crowley slander, he's an interesting character and I like him a lot! But he's not at all a punk/radical/leftist/etc, at least not as of the end of S2. I think Aziraphale's motivations are often pretty selfish as well, and his methods can be naïve, but at least he's willing to take risks to try for a kinder world. That puts him a lot further along the road to radicalism in my book.

LWA: I was thinking this afternoon about Aziraphale's plot trajectory in S2, and along the way stumbled over a different Crowley problem. Namely, this: what is Crowley /actually/ modeling for Aziraphale when it comes to working out his relationship to Heaven? Because there does seem to be a vague fandom consensus that Crowley embodies a radically oppositional relationship to "the system" (hence the meme that was going around about "the system must be dismantled" over Crowley's photo), whereas Aziraphale thinks of himself entirely within the system and can therefore only imagine reforming it. In this model, Aziraphale's inability to disentangle himself from Heaven can be conceptualized sympathetically, as a trauma response to abuse, or negatively, as moral obtuseness. But this doesn't map onto either the scripts or the novel, and definitely doesn't take into account that in the novel, the character who finally sets out the possibility of actual resistance is...Aziraphale.

The Crowley problem is that Crowley /at no point/ articulates any way of dismantling the system and rarely imagines himself existing outside of it. Instead, what Crowley tries to teach Aziraphale how to do is to construct himself as an individual negotiating the system through technicalities, rules-lawyering, outright deceit, and sometimes full compliance. In other words, going along with Heaven or Hell as far as he can, as per the Job minisode. The Arrangement subverts the Heaven/Hell dichotomy only up to the point that it exposes how both "sides" are structurally and even morally identical--"the Authorities didn't seem much to care who did anything, so long as it got done" (44)--but it doesn't provide a means of undoing Heaven or Hell as political entities. Arguably, the Arrangement lends itself to political cynicism and stasis: if the sides are interchangeable, and there is no movement except from one side to the other, then why bother moving at all? Crowley's resistance explicitly occurs /within/ the constraints of his work, which he canonically enjoys doing when it doesn't involve killing people (see: his pride in both the series and the novel over the telephone network takedown and the M25). In the Job minisode, he offers Aziraphale the possibility of disidentification and disaffection as a means to "carve out" (to borrow from S2e1) a space within an oppressive system, while still belonging to that system and even taking satisfaction from it. As of S2, he is /still/ indirectly working with Hell by tutoring Shax in exchange for information, and during the backroom discussion about Muriel he twice dismissively refers to Aziraphale and Heaven as "you lot." (Aziraphale calling Crowley and Hell the "bad guys" in S2e6 mirrors this moment.) He still, at some level, has not thought himself out of the Heaven/Hell dichotomy. Moreover, the speed with which he retreats to "carved out for myself" in S2e1 suggests that extending the language of "sides" to the two of them continues the problem instead of solving it: any major argument leads to the dissolution of "the side."* In the novel and S1, part of Adam's complaint at the airfield is that the whole concept of sides squaring off against each other is ridiculous; it's never been clear to me that the writing endorses Crowley's decision to just conceptualize them as yet another side, if the side needs to be in lockstep agreement in order to function.

Crowley's only alternative is full exit, "going off" somewhere. This poses two problems: there's "nowhere to go," as Aziraphale wearily points out in S1e3, and it leaves the system intact to oppress another day. In S2, it's unclear if Gabriel and Beelzebub will successfully "go off" for long, as they are warned onscreen that Heaven and Hell will hunt them down. Moreover, Crowley's enthusiasm for following in their energy trails is a sign of his moral limitations, which have not improved since s1 (in which, as per Gaiman and Tennant, he has no real character arc): in wanting to emulate the two "awful" characters who decide to pack off and enjoy themselves with no gratitude to Aziraphale for endangering himself, no sign that they think of anything they did over the millennia as /wrong/, and no care for anything they leave behind, Crowley inadvertently reveals that he is still trapped in the "responsibility for my actions? what responsibility?" mentality he has in both the novel and all through S1. *drags the unresolved child murder subplot from S1 out of storage, shakes it around, throws it back into storage* I know that since S1, some fans have objected that there's nothing wrong with "going off" like this, but while that's no doubt true in a general real-world sense, that has nothing to do with Crowley's narrative function as a character.

I think you can see where I'm going with this. Aziraphale's decision to return to Heaven to "make a difference" is, awkwardly enough, absolutely compatible with Crowley's own example. Crowley has not taught him how to fully resist the system, let alone dismantle it: he has taught him that the only two options are creating a fiction of personal independence within the system or packing off entirely, both of which leave Heaven and Hell fully intact. Nothing about returning to Heaven to "make a difference" conflicts with "going. along" with Heaven until he can't, as "making a difference" implies that it may be possible to expand the "going along" until there is no "can't"! Aziraphale's insight in the novel is that even as disaffected, disidentified workers, they are still complicit in Heaven's and Hell's violence and are therefore obligated to remain in order to resist Satan. This is a "hard saying" (John 6:60), but TV!Aziraphale's not-entirely-free decision** to leave for Heaven in order to "make a difference"--a decision that he certainly doesn't execute well!--rests on a sense of moral obligation that moves him further along the road to this point.

/Pace/ Nina and Maggie, through S1 and even S2 they mostly communicate just fine. What they do not do just fine is serious disagreement. The only major S1 miscommunication occurs in 1862/1967, and it occurs /because/ they're represented as not knowing how to work through this kind of argument without immediately jumping to conclusions, losing their tempers, failing to hear each other out, etc. See also S1e3, S2e1, and S2e6.

** This is an epic-length ask, so I'll stop, but the Metatron's proposal looks /back/ to Crowley's conversation with Beelzebub in s2e1 and /across/ to Maggie's and Nina's conversation with Crowley in s2e6. Nina calls Aziraphale Crowley's "partner" and the Metatron refers to their relationship as a "partnership"; both of them insist that the solution to the problem is to talk; and the resulting car crash results from selective hearing and misunderstanding on /both/ Crowley's and Aziraphale's parts (Crowley fails to apply Nina's message about abusive relationships to both Aziraphale and himself; Aziraphale misinterprets Crowley's dislike of Hell as a desire to return to Heaven).

hi LWA!!!✨ as an unrelated aside, you wouldn't believe the sheer amount of illegible notes ive had to take in order to plan out a response to this - there is so much to unpack! will try to keep things as coherent as possible, but will be jumping around back and forth a fair bit.

so the first thing that springs to mind is that by definition, crowley does not at all strike me as a radical in any sense, whether as a personal attribute or as political ideology (so to speak). i want to go into this later on, but i completely agree with your assessment - crowley seems to actively like being a demon, is a successful one, and/or at least takes unbridled satisfaction and enjoyment from it. he benefits from his place in the system, which i still think (by the by) is reasonably well-established in the hellish food chain, and he even goes beyond being a 'standard' demon by completing his work to a higher 'class' of diabolicalness than his contemporaries. he takes pride in this, as you said (another demonic trait, if we want to reductively categorise 'demonic-ness' solely by the seven sins), and is implied to see it as a particular skill or craft.

aziraphale on the other hand (as, again, i want to look at later on, but i think given the length of this ask might need to be a separate post? idk let's see how we go), seems to be the one of the two that actually resists his inherent and traditional (ie. angelic) nature, and presents as the most radical out of the both of them. he constantly toes the company line, and does things outside the scope of being an angel that his own contemporaries have outright mocked or condemned. if anything, aziraphale seems to be oppressed by his being an angel. the issue is that because of aziraphale's usually prominent nature of being a good person (note: not a good angel, but person), he still endeavours to see the best in everyone. it highlights his occasional naivety, although i do think he has become less and less naive than the audience gives him credit for. the fact that he still believes in heaven's mission statement of being the side of good isn't stupidity, i don't think it's even naivety - i just seems to me that he's holding out hope that there is still good at all. i would like to think that this hope holds; reality is, and GO would be, a depressing place without it.

back to crowley, however, and his place in the system. look - i don't want to go so far as to liken crowley to champagne socialism, but fuck it - im going to. crowley eloquently countered the concept of poverty being a virtue in the resurrectionist minisode, does it to teach aziraphale a lesson. but he doesn't, at any point as far as i can recall, pursue any avenue in which he combats this or any other unfairness existent in the world, despite evidently thinking that it is unfair. he is quick to reproach aziraphale for his ridiculous purview on human suffering, but does not do anything to set an example to aziraphale on what the alternative, 'right' thing is.

wilde made a valid point on his essay on socialism, in that elaborate and contrived altruism is a symptom of capitalist society; it's all very well to remedy the injustice and suffering forced upon those with little means to rectify it themselves, but if you don't resolve the root of the issue, the issue will persist. it's not a stretch to consider that crowley might see heaven in similarly cynical way; that they will act with charity and righteousness, but it means nothing when it does not right the wrong in the first place.

but crowley does not do this either; he recognises that the system is redundant, and that both spell equal disaster for all under its shadow... and yet a) he continues to directly benefit from it, even in s2, and b) when given an opportunity to change or even remove it, he resolves that the only solution for him (and aziraphale) is to run from it altogether. it's understandable why he wants to run, but it doesn't place him in a standing where he has any credible superiority over aziraphale choosing to make a difference (even if it may, likely, end up being futile). so, yes, as you said - crowley has once again shot himself in the foot by highlighting to aziraphale the very problem that means they cannot be free to exist as they want, and then acting *shocked pikachu* when aziraphale decides he wants to change that very thing.

continuing with a laboured political analogy here, crowley's actions, his speech, and his behaviour absolutely marks him as an individualist. despite what i think the fandom likes to portray him as, he does not appear to represent any indication of collectivism (and imo is worlds apart from acting in any capacity that would place him on the marxist-communist spectrum). aziraphale, despite his aesthetic appearances and tastes - and possibly even more impactful because of this - is much more the 'anti-capitalist' in his actions, particularly by the end of s2. i don't think it's outside the realm of possibility that he may even be teetering on the edge of social anarchism, which could be an exciting development for his character going into s3.

but getting back on track with the narrative; crowley is still working within the system, yes. i think in some part it comes back to crowley thinking that he is smarter than everyone else in hell, which is manifestly not the case. at best, he has scored a couple of hits against slightly less able (?) demons in s1, but both shax and furfur demonstrate in s2 that they have some ability in keeping up with him, even on occasion out-manoeuvring him. he seems to labour under the misapprehension in s2 that hell will leave him alone after the apocalypse, because of what aziraphale 'negotiated' for him at the end of s1:

so, thinking that hell itself is no longer interested in him, and at best is terrified of him, he thinks he can exploit them by trying to get intel from shax (who is doing the same to him - and, if the end of ep3 is any indication, does it arguably better than he does). ultimately this leads him to knowing that something is going on in heaven, but aziraphale knows about this anyway by the time crowley has an opportunity to spill the tea (another excellent irony).

what i also think is particularly insightful is that in response to beelzebub offering him a high-position in hell (possibly, given the gabriel-beelzebub context, even the highest position), crowley doesn't exactly reject it based on any preconceived notion that he is outside the system/has any moral or radical objection to it. his immediate response to the implied offer is:

"Doesn't actually sound like the sort of thing you're likely to say..."

i think it's clear that crowley is the one with the actual power, here, given how adamant and desperate beelzebub acts in the scene for a sliver of intelligence on gabriel's whereabouts... even without knowing the romantic subplot context, i don't think crowley could fail to pick up that he could literally do or say anything, and beelzebub would probably let it slide, because they need him. so, why doesn't he outright reject the proposal they put before him, in the room? why does he skirt around an answer? well, it's a card that he can put in his back pocket, and it literally keeps his foot in the door despite his protests to the contrary in ep6:

"I certainly don't need them! Look, they asked me back to Hell, I said "no!" - I won't be joining their team; neither should you!"

... crowley, literally or figuratively, does not say this when beelzebub makes their offer. so, if this - what he says in ep6 - is how he viewed said offer, why didn't he say that? why does he continue to entertain being within the system? (foreshadowing for s3? to mirror aziraphale? hmmm...)

the simplified dynamic proposed to us, at the very beginning of GO (albeit the narrative immediately launches into depicting the irony of this), of angels vs. demons, of heaven vs. hell, is that they represent good and evil respectively. so, the fact that aziraphale is presented as an angel with a bastard streak, and crowley as a demon with a hidden goodness, would suggest that they are both going against the factions that they - in the general sense - belong to. however, in a lot of respects, this is almost a double-blind.

from this introduction to modern-era crowley, you could even infer that he is in agreement with hell on armageddon, at least until the point that a) it is suddenly, actually happening, and crowley is forced to consider what it would mean (i.e. rather a crucial Dead Whale to be confronted with), and b) he is being directly dragged into it; he doesn't to be involved, nor bear any responsibility for it.

the world ending is an okay prospect for him when it's in the abstract, but when he realises that it would mean losing the world and humanity, and specifically all that it offers him, does he consider thwarting it - and enlisting aziraphale to help him do so. he doesn't suggest any notion of the apocalypse being unfair or cruel on humanity itself*, from a truly altruistic perspective that would actually put him in direct contrast to what a demon 'should' be; his only resistance to it appears to be out of what he personally stands to lose.

(*the only time he, as far as i can remember off the top of my head, shows any strong moral objection to the apocalypse is in his monologue to god about testing humanity to destruction. but this feels, in this context, to be borne less out of selfless empathy for humanity, and more as a projection of his fall, and a personal criticism of god... interesting thought, especially when you also look at how he talks to the plants/job's goats)

and that's the thing - he does ultimately seem to enjoy being a demon. he takes pride in working at what he considers a higher, more sophisticated level - the phone network, for example, in contrast to hastur and ligur's acts of lustful temptation and corruption respectively, which just like the M25 comes round to bite him on the arse. it's interesting to note ligur's line about craftsmanship because, really, despite crowley falling afoul of his own work, the 'pranks' he plays are particularly fiendish to the modern human (as is, of course, being set on fire on the motorway, but we move).

satan himself explains that he values crowley's specific brand of demon-ness, thought the M25 was an excellent idea, and even seems to deliberately feature it in the end crescendo of armageddon... crowley never intended that, sure, but by his very nature? he's a rather good/talented demon without even really trying... and seems to relish it. his perception of being a higher class of demon, as a direct result of his experience of being on earth and around humans, is equally shown in the two below statements:

because look; the way crowley puts this across is that he has a hard line when it comes to murder... but given the antichrist incident (*shakes it like a magic-8 ball, as if it's going to tell us anything different*) and various other examples (french guard, graveyard watchmen) where crowley just seems straight-up chilled about people being killed, even a child, i think we can reliably surmise that it's not exactly out of any hidden moral meaning (or at least, not entirely so). no, i think it's more to do with his statement to ligur - he literally just thinks it's beneath him.

death isn't enjoyable for him, it's not as fun, but not because he has any moral objection to it; it's just not as inventive or clever. with the tadfield manor scene, the fact that he thinks nothing of leaving the humans to be arrested for his prank (which he literally did in the first place just to prove a point to aziraphale) speaks more that this kind of result is what he considers to be more refined in terms of demonic activity, rather than out-and-out slaughter.

then we consider the pride he seems to take in his temptations - particularly of aziraphale. interpretations of sexual subtext aside for a moment, he is evidently proud of his tempting aziraphale to eat in s2, but also his ability to manoeuvre him into accepting the arrangement, by means of playing on their mutual sloth tendencies (another sin for the bingo card), and convincing aziraphale to thwart armageddon, by means of playing into aziraphale's fastidiousness to be seen as thwarting 'evil wiles' in the eyes of heaven (and yeah, the threat of hearing the sound of music for eternity - understandable).

but none of these have been for aziraphale's benefit, not entirely. he exploits the angle where aziraphale could benefit from it, but he doesnt read as doing any of these things out of solely wanting to open aziraphale's eyes to the world; it's not out of kindness or selflessness. as time goes on, he ends up doing things for aziraphale without there being benefit to himself - hamlet, the paintball stain - but then again, you could argue that it's entirely so that aziraphale would be pleased with him, would be grateful to him, and equally like him as crowley, as well as owe crowley a favour down the line. his line about owing aziraphale a lunch in recompense for 1793 suggests that crowley does, in some part, think transactionally.

suffice to say that after all of this (and tbh i could probably go on for longer), crowley isn't teaching aziraphale anything about being outside the system. crowley in fact seems to revel from being inside it. he doesnt state at any point that hell is right or wrong, but is very clear that he thinks heaven is the bane of their existence. that's not necessarily untrue, but the only time he even flickers on the concept that maybe the whole circus is redundant is at the very beginning of s2... and revisits it again at the end.

there is a very fine line between acting individualistically within the system and exploiting certain aspects of it, and "going along with hell as far as [he] can". the latter suggests that there is a breaking point to be had, the 'far as he can'. and to be fair, it does appear that crowley has one - the end of the world. three times, under the knowledge that the end times are nigh, crowley proposes they leg it; twice with the apocalypse in s1, and with knowledge of the second coming in s2 (which, as a reminder, he doesn't inform aziraphale about). as you say though, aziraphale still hasn't reached his.

but crowley's reason is intertwined with aziraphale himself; aziraphale has always demonstrated up to this point his sense of obligation to stay behind to fight, to try to resolve things and work out a way to save everything and everyone - even to the sacrifice of his own personal happiness. even beyond a sense of obligation, i think aziraphale just feels that it's, ultimately, the right thing to do - another lesson that crowley taught him; to do what aziraphale considers to be right, despite what anyone else tells him.

aziraphale wants to be with crowley, that is never in question, but the method in which either of them ever sees this as being a reality is so irreconcilable that there's no solution to it. aziraphale was, absolutely, asking something inconceivable of crowley - but the fact remains that crowley demonstrates that he will not sacrifice himself for any concept of a future where there is no necessity to simply 'go along as far as he can'. it's a boundary crowley has drawn, and rightly so, but that doesn't automatically mean that aziraphale must surrender his own boundary in kind.

crowley's response to reaching this point is to abandon the situation altogether, which not only shows that he has learnt nothing about aziraphale from s1 in this respect, but it also doesn't change a single thing about the circumstances they find themselves in... and it would only be a temporary solution. even if he and aziraphale were to run, to essentially seek sanctuary elsewhere... well, where could they possibly go, and what force exists that could grant it to them? aziraphale recognises this, and i think crowley secretly does too, but doesn't - once again - want to address it.

last note, before i continue talking myself in circles - i find it interesting how flimsy the concept of 'their side' seems to be; in s1, aziraphale is the one to reject it when crowley pushes it at the bandstand, when aziraphale is still very much hanging onto the faith that heaven might see reason. and then, in s2, when it seems that, in the four years that has passed, aziraphale has relaxed enough re: clapback from heaven to fully accept what 'their side' means. however, crowley quickly retracts it in ep1 when aziraphale isn't acquiescing to him re: sheltering gabriel, out of what im perceiving is self-preservation.

but the hurt with which aziraphale remarks on this retraction seems like it was a rather cutting betrayal (that, surprise surprise, is not even addressed), and it's not really any wonder that aziraphale withdraws, offering crowley instead an opportunity to leave, whilst making plain how disappointed he is. crowley then reacts with indignation that aziraphale would essentially dismiss him, "oh, right, this is how you wanna do it?", as if that's not the very thing he himself was intimating a moment previous. as you noted is remarked by adam - the concept of having a side at all, if it's this weak and delicate (and frankly, outgunned by heaven and hell collectively), is patently ridiculous.

#sorry to add to an already long post only to basically agree with everything lol#he's just very neat to examine as a character vs how people perceive him!#especially with a tv fandom that seems to skew younger#discussion#snakepost

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

One thing I love about Crowley --never stated, but consistently shown-- is that he is, at heart, an engineer.

I have a few different things to say about that. Let's unpack them.

As the Unnamed Angel, we see his designs for the Pillars of Creation are millions of pages long, comprised of cramped text, footnotes, diagrams, schematics etc. It's very...Renaissance polymath, in the way it implies a particular intersection between artist and inventor.

Also: in the naked romanticism with which he views his stars.

We already knew he made stars, but in s2 we learn that he did NOT sculpt them one-at-a-time. He designed a nebula ("a star factory," he says) that will form several thousand young stars and proto-planets, and all --beyond getting the 'factory' running-- without him lifting a finger. We also learn that these young stars and proto-planets stand in contrast to those made by other angels, which are going to come 'pre-aged.'

...I'm reminded of Hastur and Ligur's approach to temptations. Damning one human soul at a time, devoting singular attention to it over the course of years or decades, and how that stands in contrast to Crowley's reliance on, quote, 'knock-on effects.'

Ligur: It's not exactly...craftsmanship. Crowley: Head office don't seem to mind. They love me down there.

Hm.

I'm also reminded of the M25.

The M25 may not be as grand as a nebula (sentences you only say in GOmens fandom...), but LIKE his nebula it's an intricate, self-sustaining engine that does Crowley's work for him, many times over. Again.

That's some pretty neat characterization --and so is the indication of Crowley's disinterest in victimizing anyone tempting individual people. It takes a considerable amount of planning and effort (and creeping about in wellies), but in accordance with his design the M25 generates a constant stream of low-grade evil on a gigantic scale.

Cumulatively gigantic, that is. Individually? Negligible.

But no other demon understands human nature well enough to parse that one million ticked-off motorists are not, in any meaningful way, actually equivalent to one dictator, or one mass-murderer, or even one little influential regressive. That's the trick of it. Crowley gets Hell's approval (which he NEEDS to survive, and to maintain the degree of freedom he's eked out for himself while surviving), and at the same time ensures that any actual ~Evil influence~ is spread nice and thin.

It's some clever machinery. And he knows it, too:

The Unnamed Angel and Crowley are both proud of their ideas.

(musings on professional pride, Leonardo da Vinci, the crank handle, and 'the point to which Crowley loves Aziraphale' under the cut)

In the 1970's Crowley gives a presentation on the M25, projector and all, to a room full of increasingly impatient demons. Maybe the presentation was work-ordered; the 'can I hear a WAHOO?' definitely wasn't.

Before the Beginning, the Unnamed Angel can barely contain his excitement about his nebula. Aziraphale manages a baffled-but-polite, "....That's nice...! :)"

11 years ago, Hastur and Ligur want to 'tell the deeds of the day,' and Crowley smiles to himself because (according to the script-book) he knows he has 'the best one.'

(Naturally, his 'deed' has nothing to do with tempting anybody, and everything to do with setting up a human-powered Rube-Goldberg machine of petty annoyance. Oodles of 'Evil' generated; very little harm done.)

They don't get it, of course. That's also consistent.

Nobody ever knows what the hell he's talking about.

It didn't make it on-screen, but, in both the novel AND the script-book, Crowley was friends with Leonardo da Vinci. The quintessential Renaissance polymath. That's where he got his drawing of the Mona Lisa --they're getting very drunk together, and Crowley picks up the 'most beautiful' of the preliminary sketches. He wants to buy it. Leonardo agrees almost off-the-cuff, very casual, because they're friends, and because he has bigger fish to fry than haggling over a doodle:

He goes, "Now, explain this helicopter thingie again, will you?" Because he's an engineer, too.

(It is 1519 at the latest, in this scene. Why the FUCK would Crowley know about helicopters, and be able to explain them, comprehensively, to Leonardo da Vinci?

...Well. I choose to believe he got bored one day and worked it out. Look, if you know how to build a nebula, you can probably handle aerodynamics. And anyway, I think it's telling that this is his idea of shooting the shit. 'A drunken mind speaks a sober heart,' and all. He probably babbled about Aziraphale enough to make poor Leo sick)

Leonardo da Vinci is the only person Crowley has any keepsakes or mementos of, apart from Aziraphale.

Think about that, though. Aziraphale's bookshop is bursting with letters, paintings, busts, and personalized signatures memorializing all the humans he's known and befriended over 6000 years (indeed: Aziraphale has living human friends up and down Whickber Street. He's part of a community).

Crowley doesn't have any of that. It's just the stone albatross from the Church (for pining), the infamous gay sex statue (for spicy pining), the houseplants (for roleplaying his deepest trauma over and over, as one does), and this one piece of artwork, inscribed, "To my friend Anthony from your friend Leo da V."

To me, at least, that suggests a level of attachment that seems to be rare for Crowley.

...Maybe he liked having someone to talk shop with? Someone who was interested? Someone engaged enough to ask questions when they didn't immediately understand?

...Anyway.

There's also the matter of the crank handle.

This thing:

This is one of the subtler changes from the book. In the book, Crowley knows Satan is coming and, desperate, arms himself with a tire iron. It's the best he can do. He's not Aziraphale; he wasn't made to wield a flaming sword.

The show, IMO, improves on this considerably. Now he, like Aziraphale, gets to face annihilation with what he was made for in his hand. And it's not a weapon, not even an improvised one like the tire iron.

He made stars with it.

[both gifs by @fuckyeahgoodomens]

If you Google 'crank handle,' you'll get variations on this:

Crank handles have been around for centuries. Consisting of a mechanical arm that's connected to a perpendicular rotating shaft, they are designed to convert circular motion into rotary or reciprocating motion.

Which is to say they're one of the 'simple machines,' like a lever or a pulley; the bread and butter of engineering. You'll also get a list of uses for a crank handle, archaic and modern. Among them, cranking up the engine of an old-fashioned car... say, a 1933 Bentley. That's what Crowley has been using his for, lately. But he's had it since he was an angel and he's still, it seems, very capable of it's angelic applications.

I know everyone has already said this, but: I REALLY LIKE that when he needs to channel the heights of his power, he does so not with a weapon but with a tool. Practically with a little handheld metaphor for ingenuity, actually. One from long-lost days when he could make beautiful things.

(And he loved it. Still loves it, I'd say --he incorporated it into the Bentley, didn't he?)

Let Aziraphale rock up to the apocalypse with a weapon: he has his own compelling thematic reasons to do exactly that. Crowley's story is different, and fighting isn't the only way to express defiance. And if you've been condemned as a demon and assumed to be destructive by your very nature, what better way than this?

He made stars. They didn't manage to take that from him.

Neither Crowley nor Aziraphale are fighters, really --they have no intention of fighting in any war. They'll annoy everyone until there's no war to fight in, for a start. But between the two, if one must be, then that one is Aziraphale. Principality of the Earth, Guardian of the Eastern Gate, Wielder of the Flaming Sword... all that stuff. Even if he'd prefer not to, it's very clear that Aziraphale can rise to the occasion, if he must.

Crowley was not that kind of angel. He wasn't a Principality. He has no sword.

...And yet.

It's Crowley who protects. He's the one who paces, who stands guard, who circles Aziraphale and glares out at the world, just daring anyone else to come near.

In light of everything else I've said here, I think that's interesting.

Obviously part of it is that Aziraphale enjoys it and, you know, good for him. He's living his best life, no doubt no doubt. But what about Crowley? What's driving that behavior, really?

Have you heard the phrase, 'loved to the point of invention'? Well, what if 'the point of invention' was where you started? What if where you end up involves glaring out at the world, just daring anyone else to come near? What is that, in relation to the bright-eyed thing you used to be?

What do we name the point to which Crowley loves Aziraphale?

...Thinking about how an excitable angel with three million pages of star design he wants to tell you all about...becomes a guard dog. Is all.

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

aziraphale and castiel could NOT hang out bc aziraphale is a snob and cas knows fucking nothing about high culture spends all his time with two guys who definitely made him watch south park and has never been to a nicer restaurant than MAYBE ruby tuesday’s. working class angel hero. sorry about this post

62K notes

·

View notes