Text

SOCIOLOGY ON THE ROCK, Issue 24

Editor and Founder: Stephen Harold Riggins

Webmaster: Zbigniew Roguszka

Issue 24 in PDF

0 notes

Text

This issue

Patrick Gamsby: On the Sociology of Boredom.

Katherine Pendakis and Elisabeth Rondinelli: Towards a Sociology of Failure.

Lynda Harling Stalker: Revisiting Wool and Needles in my Casket.

Harley Dickinson and Terry Wotherspoon: A Sociological Rebel with a Cause: Remembering Les Samuelson (1953-2022).

Stephen Harold Riggins: Gianfranco Poggi (1934-2023)

0 notes

Text

Retirement Party for Susanne Ottenheimer.

Professor Judy Adler: "Suzanne has served as one of the department's most dedicated teachers for many, many years -- a true professional educator, generous in the warmth, attention and welcoming availability she has consistently mustered for students. Year in and year out, Suzanne has helped to make the Sociology Department a welcoming place for students and faculty alike."

Front row, left to right: Pouya Morshedi, Linda Cohen, Susanne Ottenheimer, Adela Kabiri, and Lisa-Jo van den Scott.

Back row, left to right: Ruby Bishop, Peter Sinclair, Shayan Morshedi, Fran Warren, Malin Enstrom, Adrienne Peters, Colleen Banfield, Daniel Kudla, Audrey O'Neill, Jeffrey van den Scott, and Bob Hill.

0 notes

Text

On the Sociology of Boredom

By Patrick Gamsby

“Why would you study boredom? Is it boring?” Sometimes serious, sometimes in jest, these are common questions awaiting anyone who is interested in the topic of boredom. But really, why study boredom? Perhaps at first blush it may seem unworthy of serious research. It is a common experience found throughout everyday life, sure, but probe a little bit deeper and it reveals itself to be a complex phenomenon. It has received attention in sociology dating back several decades (Klapp 1986), but it is perhaps most often associated with psychology (Fenichel 1953), and, to a lesser extent, with literary studies (Spacks 1995), religious studies (Raposa 1999), and philosophy (Svendsen 2005). I would argue that it is actually most appropriate as a topic of sociological inquiry, given the historical, social, and spatial aspects of its emergence and pervasiveness in the modern world. As well, the study of boredom fits with Peter Berger’s assertion in his Invitation to Sociology: “It can be said that the first wisdom of sociology is this – things are not what they seem” (Berger 1963: 22). Indeed, I would argue that boredom is not what it seems.

Painting titled "Boredom" (1893) by French artist Gaston La Touche.

I first encountered the sociology of boredom while I was an undergraduate student at the University of Western Ontario, many moons ago. In the second term of my fourth year I took a course offered by Dr. Michael Gardiner on the Sociology of Everyday Life. At first, I was taken aback by the content, as it was all so different from everything I had learned in my sociology degree up to that point. As I soon found out, boredom and everyday life are extraordinarily complex in their ordinariness. Here, it became clear that Hegel was on to something with his maxim “the familiar is not necessarily the known” (Gardiner 2000: 1). This became especially apparent to me when I had to give a class presentation of an article by Joe Moran titled “Benjamin and Boredom.” This opened my eyes to the complexity of boredom, its seriousness as a topic, and the great potential of the sociology of seemingly trivial things.

I would go on to do graduate work on boredom, specifically on the latent theory of boredom in the work of Henri Lefebvre which would also be the topic of my first book (Gamsby 2022). There is an interesting parallel between Lefebvre and boredom, as both are familiar entities but not especially known. Lefebvre argued that a study of boredom ought to be part of an inquiry into everyday life. For example, in the second volume of his Critique of Everyday Life, published in the original French in 1961, Lefebvre noted the importance of boredom for his overall project: “On the horizon of the modern world dawns the black sun of boredom, and critique of everyday life has a sociology of boredom as part of its agenda” (Lefebvre 2002: 75). Despite this assertion, Lefebvre did not pursue a sociology of boredom. In assembling the fragments of his theory that are scattered across his vast oeuvre, I set out to construct his unrealized sociology of boredom. In doing so, boredom is revealed to be a dialectical phenomenon, one that is tied to both time and space, modernity, everyday life, urbanism, suburbia, pop culture, avant-garde art, literature, leisure, work, among other areas. In a word, it is complex.

Boredom’s relationship to history is part of its complexity. Simply put, there are three basic views on boredom and history (Gamsby 2019: 210-211). The common view is to pay little attention to boredom, seeing nothing interesting or unique about it. It is part of time immemorial. In such a view, as soon as humans walked the earth they were probably bored with it. Alternatively, there are those that take boredom to be worthy of serious study, but nevertheless view it as an ahistorical experience, often seeing historical terms and experiences such as acedia as being synonymous with boredom (Kuhn 1976). Finally, there is the historical view, which is one I subscribe to, that boredom is an historically specific experience that emerged with modernity (Goodstein 2005). This last position lends itself especially well to sociological analysis. It is one that looks to the Oxford English Dictionary as proof of the nineteenth century emergence of boredom, as well as one that takes into account the specific conditions of modernity with the speeding up of society, the “annihilation of time and space,” and shifts in perception that came with the advent of steam power (Schivelbusch 2014).

Even if some historical parameters can be placed around it, boredom is an elusive subject. It may appear in unexpected places, both out in the world and in scholarship. In sociological literature it may be hiding away amidst other topics. As such, it is not always so easy to find outside of specifically focused articles and books. For example, my favourite definition of boredom comes from Marx in his 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts where he notes that boredom is a “longing for a content” (Marx 1992: 398). I stumbled upon this definition, and I believe that such a fortuitous encounter is part of the thrill and the challenge of studying boredom. As well, part of the challenge is knowing that it may be called something else, or alluded to, or even implicit in a text. Is the “problem with no name” in Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique not boredom? The suburban housewife’s question “Is this all?”(Friedan 2001: 57) could be seen as a quantitative query, perhaps one that is economic in nature, but I argue it is one that emerges out of boredom in Marx’s sense of the term as a longing for content, which is to say a utopian wish for something else. How about Simmel’s depiction of the blasé personality in his essay “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (Simmel 1997: 174-185)? Is this adaptation to the speed, density, and rhythms of the big city not also boredom? It has been argued that it is (Goodstein 2005: 249-280).

Can you ever objectively see boredom in the world? Yes and no. Aside from its declaration, there are certain visual cues, certain gestures, that may indicate boredom. A yawn is one such example. But not all yawns are created equal. Perhaps someone is sleep deprived, or perhaps they simply need to get oxygen to their brain. There have been attempts to measure one’s boredom proneness (Farmer and Sundberg 1986), but I am wary of such psychological questionnaires. If someone is actually bored, they may try to disguise it, as there is a certain stigma associated with it. Who among us wants to be called boring? Who among us wants to admit to being bored? For the former question, it would be few, if any. For the latter question, it depends. To be bored as a young child is often seen as a psychological deficiency on the part of the child. The boredom of a teenager could also be seen as a deficiency if viewed by parents or teachers, but to the teenager’s friends it could be a mark of coolness. For these various children, to be bored by something is to be either below it or above it, in a certain sense, even if one is only posing as bored. But, of course, one can be bored by tarrying with something. That is, not above it, not below it, but staying with it. As such, there is more than one way to be bored.

But is there only one kind of boredom? It may seem that way, based on how it is discussed in everyday life as just a matter of time dragging, but it is more complex than that. In his 1929/1930 lectures, Martin Heidegger argued that boredom is a fundamental mood. For him, there are three different types of boredom, each of which is fluid, each has the characteristics of “being left empty” and “being held in limbo,” and each is more profound than the last. The first type of boredom is an objective boredom in which we are “bored by something.” It is a situation where there is a certain boringness, a sort of boring quality that you can point to and say “This bores me.” Conversely, the second type of boredom moves from objective to subjective. Here, one experiences boredom but cannot definitively identify the cause. It is not a matter of this or that, but something else, perhaps oneself, that bores. Finally, the third boredom is referred to as “profound boredom,” which is a type of existential boredom. It is something beyond the objective and subjective forms mentioned above and is only accessible if it is not counteracted. It is a boredom that brings one closer to questioning time itself, closer to an authentic philosophical position (Heidegger 1995). Very different from a psychological deficiency. Heidegger’s is but one interpretation of boredom’s diversity, but there are others that believe there are many more than just three types of boredom (Tochilnikova, 2021: 27-35).

What I have tried to convey here is that boredom is not simple. Indeed, attempting to delineate the contours of boredom can prove to be a tricky endeavour. This is part of the opportunity and challenge of its study. In general, boredom studies have been around for several decades, but this area has developed greatly over the last couple of decades. There is now an International Society of Boredom Studies, which publishes a peer reviewed journal and hosts conferences. And, along with numerous articles and books, a few collections of boredom studies have been published fairly recently (Gardiner and Haladyn, 2017; McDonough, 2017). These are all signs of a burgeoning area of inquiry. Accordingly, in returning to the two questions posed at the beginning of this piece, I would say that boredom is interesting and by no means boring. There is a great deal of work to be done in the sociology of boredom, well beyond what I have written here. If you agree that things are not what they seem, and the familiar is not necessarily the known, then you, too, may be interested in the sociology of boredom.

Bibliography

Berger, Peter L. (1963) An Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books.

Farmer, Richard and Norman D. Sundberg (1986) “Boredom Proneness – The Development and Correlates of a New Scale,” Journal of Personality Assessment 50(1), 4-17.

Fenichel, Otto (1953) “On the Psychology of Boredom.” In The Collected Papers of Otto Fenichel: First Series. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 292-302.

Friedan, Betty (2001) The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Gamsby, Patrick (2019) “Boredom – Emptiness in the Modern World.” In Michael Hviid Jacobsen (Ed.) Emotions, Everyday Life and Sociology, 209-224. London: Routledge.

Gamsby, Patrick (2022) Henri Lefebvre, Boredom, and Everyday Life. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Gardiner, Michael E. (2000) Critiques of Everyday Life. London: Routledge.

Gardiner, Michael E. and Julian Jason Haladyn (Eds.) (2017) Boredom Studies Reader: Frameworks and Perspectives. London: Routledge.

Goodstein, Elizabeth S. (2005) Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Heidegger, Martin (1995 [1983]) The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, Solitude (William McNeill and Nicholas Walker, Trans.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

International Society of Boredom Studies https://www.boredomsociety.com

Journal of Boredom Studies http://www.boredomsociety.com/jbs/index.php/journal

Klapp, Orrin E. (1986) Overload and Boredom: Essays on the Quality of Life in the Information Society. New York: Greenwood Press.

Kuhn, Reinhard (1976) The Demon of Noontide: Ennui in Western Literature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lefebvre, Henri (2002 [1961]) Critique of Everyday Life: Volume II, Foundations for a Sociology of the Everyday (John Moore, Trans.). London: Verso.

Marx, Karl (1992) Early Writings (Rodney Livingstone and Gregor Benton, Trans.). London: Penguin Books.

McDonough, Tom (Ed.) (2017). Boredom. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Moran, Joe (2003) “Benjamin and Boredom,” Critical Quarterly 45(1-2), 168-181.

Raposa, Michael L. (1999) Boredom and the Religious Imagination. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang (2014) The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Simmel, Georg (1997) Simmel on Culture (David Frisby and Mike Featherstone, Eds.). London: Sage Publications.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer (1995) Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Svendsen, Lars (2005[1999]) A Philosophy of Boredom (John Irons, Trans.). London: Reaktion Books.

Tochilnikova, Elina (2021) Towards a General Theory of Boredom: A Case Study of Anglo and Russian Society. London: Routledge.

0 notes

Text

Towards a Sociology of Failure

By Katherine Pendakis and Elisabeth Rondinelli

Katherine Pendakis, PhD York University, teaches in the Department of Social and Cultural Studies at the Grenfell campus of Memorial University. Her previous research as an ethnographer has been about migration, diasporic identity, and kinship in Greece, Vietnam, and Canada. Publications by Katherine Pendakis have appeared in Citizenship Studies, Journal of Refugee Studies, The Asia-Pacific Journal, and Surveillance & Society.

Professor Katherine Pendakis.

Elisabeth Rondinelli, PhD York University, is an ethnographer and cultural sociologist. She teaches in the Department of Sociology at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax. Topics of her research include the sociology of emotions and gender-based online violence.

As Millennial scholars born into the Canadian working class, we (Liz and Kate) were raised on a standard diet of “work hard, get ahead” at a time when it still felt possible to meet the traditional markers of adulthood: graduating with a college or university education; getting a job with a stable income; buying a home; building a family with partners, pets, and maybe children. But as Silva (2013) has shown, this trajectory has become less possible for young adults today. As neoliberalism has reduced state supports, well-paying union jobs have disappeared, and students have become heavily indebted, Millennials, and more recently Gen Z, are searching for alternative ways of claiming self-worth.

We have been researching an emerging “culture of failure” in North American society. This culture is mainly aimed at, concerned with, and produced by Gen Z and Millennials, and is expressed in mainstream media and social media ranging from observations of changes in the labour market (like the “great resignation” and “quiet quitting”) to reflections on the mundane failures of everyday life (like “goblin mode” and “bed rotting”). At the centre of our analysis is an examination of how discourses of failure convey a critical and lucid understanding of the limitations of our contemporary social systems as well as traditional markers of adulthood. This departs in striking ways from dominant approaches to failure.

Traditional narratives of failure tell us that it is best thought of as something from which to learn and a necessary stepping stone on the way to success and self-development. A simple Google search will yield hundreds of motivational quotes by entrepreneurs, athletes, political personalities, and influencers – living and dead – that frame failure as an unlikely teacher, urging us to keep trying. Similar aspirational sentiments are reproduced everywhere, from schools and workplaces, to pillows, kitchen walls, and coffee mugs: “Fail again. Fail better!” From this perspective, chronic failure that does not yield identifiable self-development is consequently seen as evidence of an individual’s lack of grit, perseverance, work ethic, or self- discipline.

Professor Elisabeth Rondinelli.

Certainly, there are many sociological analyses that tell us about the power of this framing. In fact, critical sociologists have long been preoccupied with the power and pervasiveness of individualistic discourses that encourage people to take personal responsibility for their circumstances and status. Working with theoretical contributions from key critical social and political theorists like Bauman (2000), Beck (1992), Bourdieu (1977, 1986), Brown (1995), Foucault (1997), and Rose (1990, 1999), studies have explored the diverse manifestation of these discourses, tracking how individualism shows up, for instance, in entrepreneurial subjectivity (Bröckling 2015), the meritocratic myth (Calarco et al. 2022; Mijs 2021), moral or flexible citizenship (Ong 1999; Valverde 1991), and therapeutic and self-help narratives (Illouz 2007, 2008; Silva 2013). Each of these discourses frames one’s experiences and position in social life as a consequence of one’s own individual behaviour and decision-making. At the centre of each is the self: wealth, prestige, strong relationships, and good health are manifestations of one’s will; financial precarity, divorce, and illness reflect poor decision-making and a lack of self-discipline. We have found that for critical sociologists, self-blame and talk of failure is simply a reflection of these discourses – one that ultimately serves to reproduce social inequality by blocking the possibility of collective awareness and critique of social structures.

A notable example of this tradition is Silva’s treatment of working-class Millennials’ reliance on therapeutic narratives to come to terms with their sense of failure. With the assistance of self-help books and media, therapists and support groups, Millennials develop a therapeutic narrative through which they position themselves as having succeeded in overcoming their personal demons (like pathological family relationships, bad habits, learning challenges, mental illness, and addiction). At the same time, however, Silva interprets this tendency as a depoliticizing force, turning young people inward and “hardening” them against themselves and others. Silva documents instances in which interviewees blame themselves or others for failing to achieve traditional markers of adulthood or for not having more success in their journey of self-development. Failure and therapeutic narratives thus go hand in hand.

While Gen Z has inherited this now well-entrenched therapeutic narrative and the self-help culture that goes along with it, we argue that there is also evidence of an emerging generational disenchantment with the allure of perpetual self-improvement. Against hustle culture, against “the grind,” against performative productivity, and burning the candle on both ends, Gen Z has at their disposal a new framework through which they can understand these norms to be “toxic” remnants of an outdated work-obsessed culture. Foregoing the fantasies of meritocratic social mobility and reward, Gen Z can now appeal to slowness, staying put, and opting out.

Arguably, generational divides have been well-documented, characterized by mutual disdain, hostility or suspicion: the young consider the old to be out of touch; the old call the young idealistic and irresponsible, naive to the ways of the world. But we claim that what marks this generation – Gen Z in particular – is the historically specific set of tools they have to articulate their shared condition. This shared condition includes having been born into internet culture and digital practice, the mainstream acknowledgement that it may be too late to do anything about climate change, the widespread forecasting of declining quality of life, and the discourses of mental health crises and isolation wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is in this context that a “culture of failure” begins to make sense.

As sociologists, what tools do we have to make sense of this emerging culture of failure? In the absence of an existing “sociology of failure,” we are currently conducting a systematic overview of the discipline’s implicit attempts to understand failure, with an aim to developing methodological and conceptual tools for a more expansive treatment of failure. Framing our overview in terms of the promises and limitations of these attempts, we examine contributions from both critical and cultural sociology. We show that critical sociologists’ preoccupation with how ideologies justify inequality leads them to treat failure as evidence of internalized individualism, false-consciousness, or neoliberal subjectivity. Since our interest is precisely in the critical capacities that are evident in contemporary discourses of failure, we argue that the critical sociological tradition requires considerable intervention if it is to recognize and explore how a culture of failure can also be a culture of critique.

We then turn to cultural sociology. We show that cultural sociologists’ focus on agentic forms of meaning-making activity position them to offer a more expansive analysis of discourses of failure. While we do indeed discover these, we argue that, in practice, cultural sociologists tend to avoid taking up failure as a social fact requiring careful theoretical elaboration and detailed empirical investigation. Indeed, the closer cultural sociologists come to investigating failure, the more they rely on analyses from critical sociology that reduce actors’ talk of failure to evidence that they lack critical capacity and an understanding of the conditions that shape their lives.

Ultimately, our project tracks a generational impulse that seems to be wresting failure from the therapeutic narrative and deploying it instead to advance a collective critique of social systems and the contemporary moment. To meet the emergence of this collective critique, we argue that sociology must reckon with its reductive treatments of failure.

References

Bauman, Zygmunt (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Beck, Ulrich (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1986) “The Forms of Capital.” In John G. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood, 241-258.

Bröckling, Ulrich (2016) The Entrepreneurial Self: Fabricating a new type of Subject. London: Sage.

Brown, Wendy (1995) States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Calarco, Jessica M., Ilana Horn, and Grace A. Chen (2022) “You need to be more Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities,” Educational Researcher 51(8), 515-523.

Foucault, Michel (1997) “Technologies of the Self.” In Paul Rabinow (Ed.) Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth: The Essential Works. New York: The New Press, 223-251.

Illouz, Eva (2007) Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Illouz, Eva (2008) Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-help. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mijs, Jonathan (2021) “The Paradox of Inequality: Income Inequality and Belief in Meritocracy go Hand in Hand,” Socio-economic Review 19(1), 7-35.

Ong, Aihwa (1999) Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Rose, Nikolas (1999) Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. New York: Routledge.

Rose, Nikolas (1999) Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Silva, Jennifer M. (2013) Coming up short: Working Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valverde, Mariana (1991) The Age of Light, Soap, and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885-1925. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

0 notes

Text

Revisiting Wool and Needles in my in my Casket

By Lynda Harling Stalker

Lynda Harling Stalker is Professor and Chair of Sociology at St. Francis Xavier University. She is engaged in research in the areas of culture, craft, cultural work, belonging, rural outmigration, islandness, and narrative inquiry. Her research enlivens the emotional, embodied, and material aspects of creative production and culture.

In the late fall I received a lovely email from Stephen Riggins asking me to reflect back on my MA research conducted in Newfoundland. An instant smile came across my face as I was quite chuffed to be asked. Stephen’s invitation sparked another memory from a couple of years ago when I received an unexpected but very welcomed email from Doug House. Doug had been my MA supervisor and was influential in my development as an academic. He wrote that he had given a presentation to NONIA (Newfoundland Outport Nursing and Industry Association) about the history of the organisation. His father, Edgar (House and House 2015), had written a small book on NONIA’s history (1990), so Doug is the natural choice to continue this legacy. What the current members did not know was that from 1998-2000 I had interviewed NONIA knitters from across the province as part of my graduate programme. This research has become a document (albeit by a very junior academic) of a particular time and place. The women knitters were dealing with a difficult time in Newfoundland history.

Of late, Newfoundland knitting has again become popular following the publication of Christine Legrow and Shirley A. Scott’s Saltwater Knitting Books (2018-2022). These books are filled with patterns to knit double-ball mittens, trigger mittens and socks that are seen as a traditional Newfoundland knitting style. Knitted items have been so integral to Newfoundland culture that items were christened with names for objects not used elsewhere: vamps are oversocks that reach the ankle; cuffs are mittens; trigger mitts have a separate covering for the thumb and index finger (Dictionary of Newfoundland English). The knitting was always practical and well-executed and important work done by women. Magot Iris Duley (1993) talks about how the “iconic grey sock” knit by Newfoundland women during WWI led to them gaining the vote in 1925. It was very much women’s work throughout Newfoundland history, although many of the knitters I interviewed in the late 1990s said there was the proverbial man around the Bay who could knit as good as a woman.

NONIA started in 1925 when the then-Governor’s wife, Lady Allardyce, decided that Newfoundland women’s skill in knitting could / should be used to improve the health of their families. Money from selling knitted garments in St. John’s would fund the salaries of nurses to be stationed in the Outports across the island. The skills of the knitters were quickly recognised by many, including one of the first sponsors, Queen Mary, and the Canadian government christened a naval ship the HMS NONIA. The operations of NONIA have stayed much the same throughout its history. The organisation would mail out wool and patterns to knitters across the province and the women would mail back the finished garments. These garments would be sold in the store located on Water Street in St. John’s. While nurses’ salaries are no longer funded, knitters receive a piece rate for their work. This is all done as a not-for-profit organisation.

I arrived at Memorial in 1998, when the cod moratorium and the fallout from it was still fresh. Outmigration, particularly of youth and working-age adults, was reaching epic proportions. It was a time of unprecedented social, economic, political, cultural, and environmental change that left Newfoundlanders unsure what the future would hold. In this climate, I set out to interview 19 women who knit for NONIA. More than half the women were 60+, about 80% were married, and a little over 40% started knitting with NONIA around the time of the cod moratorium.

When I analysed the knitters’ narratives that were shared with me, I took a Weberian-like approach. I was influenced at the time by the work of Colin Campbell (1996a, b; 1999), which focussed on analysing the meaning and motivation behind one’s actions. Through my analysis I highlighted that the women were motivated to knit because it allowed them to pass the time, do some challenging work, relaxation, and knitting provided a sense of accomplishment and pride. As Mrs. Parson said, “It’s something that you worked at, and you’re completely satisfied; it’s self-assuring.” (All knitters’ names are pseudonyms.) The motivation was quite intrinsic. It wasn’t about external reward or validation; the motivation to knit was linked to ideas of self and almost self-preservation.

The meaning that I argued that the knitting had for the women included filling in the time, a link between generations, enacting and embodying a female identity and being a part of Outport life. Knitting was always part of the planning and figured into much that they did. This was illustrated when Mrs. Murphy articulated when preparing for a trip to Ontario, “See them two boxes there? That’s full of wool. So now I’m going up to Ontario and I’m going to take them with me. What I’m going to do is put them in the mail.” Others stated similar things; knitting was so integral to who they were and what they did that even when going on holiday they could not be parted from their knitting.

NONIA’s role in the knitter’s lives was important but not in the way many would assume. It was often speculated that organisations like NONIA provided much needed economic benefits to Outport women during the cod moratorium era. That wasn’t the case for these women. Yes, they wished to be paid and knitting for NONIA was not out of the goodness of their hearts. As Mrs. Foley stated, “I knit for NONIA for pastime. I like knitting but I found I was knitting a lot of things that I didn’t need, just to knit, before I started with NONIA. The only thing about getting paid for knitting or any other hobby, you never will get paid enough for the time you put in it, but if you enjoy what you are doing that don’t matter.”

What NONIA provided for the knitters was access to good quality materials to knit with at no cost, provided someone to knit for, and there were no time pressures. NONIA’s value to the knitters went beyond the pay they received but what NONIA did was allow these women to be able to do craftwork that allowed them to demonstrate that despite the turmoil caused by the cod moratorium they were Newfoundland (Outport) women. As Mrs. Budgell said, “I get women who say, ‘I don’t even want to knit’ ‘cause they say it’s from the Bay. You know I came from the Bay and so what? I love to do it!” The creation of knitted garments with a purpose meant that the women could, through practice and materiality, hold onto this identity that was so important to them.

A dear colleague of mine at St. Francis Xavier University, Dan MacInnes, said that the last way we can assert our identity is through our tombstones. While this may sound a bit morbid, for some of the women I spoke with this is very much the case – although it was through the placement of material items in their coffins. When talking about how important knitting was to who they were and what they did, Mrs. Brown and Mrs. Hickey said that they will be buried with wool and needles in their casket. Mrs. Hickey repeated something her children had said, “Mom, we’ll have to put some wool and knittin’ needles down in the box with you ‘cause you always got it in your hands.”

This sentiment speaks to what the women identify with and how others identified them as knitters (Jenkins 2000). I’m sure both Mrs. Brown and Mrs. Hickey have passed – I wonder if these wishes were carried through.

I think if I were to do this project again, it is belonging that would be my centralising concepts. As May (2013: 3) argues, “belonging acts as a kind of barometer for social change.” The women’s talk about the importance of knitting to them speaks to the importance of belonging to Newfoundland, particularly the outports, and the kind of knitting they did demonstrates the relational, cultural and material elements of belonging (May 2013). It seems that this desire to be seen as a Newfoundlander, belonging to the place and its people, was heightened due to the dramatic changes the cod moratorium brought to the province. If I were to advise my younger self, I would urge me to delve more into the narratives about how belonging in light of the social changes manifests itself through the practice of knitting. Maybe that will be my next project….

Works cited

Campbell, Colin (1996a) “On the Concept of Motive in Sociology.” Sociology 30(1), 101-114.

-- (1996b) The Myth of Social Action. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

-- (1999) “Action as will-power.” The Sociological Review, 47(1), 48-61.

Duley, Margot Iris (1993) “‘The Radius of her Influence for Good’: The Rise and Triumph of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in Newfoundland, 1909-1925.” Pursuing Equality: Historical Perspectives on Women in Newfoundland and Labrador. Linda Kealey (Ed.). St. John’s: ISER Books.

Harling Stalker, Lynda (2000) “Wool and Needles in my Casket: Knitting as Habit among Rural Newfoundland Women.” Unpublished MA thesis. Department of Sociology, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador.

House, Edgar (1990) A Way Out: The Story of NONIA 1920-1990. St. John’s: Creative Publishers.

House, Doug and Adrian House (2015) An Extraordinary Ordinary Man: The Life Story of Edgar House. St. John’s: ISER Books.

Jenkins, Richard (2000) “Categorization: Identity, Social Process and Epistemology,” Current Sociology 48(3), 7-25.

Kirwin, William J. (Ed.) et al. (1990[1982]) Dictionary of Newfoundland English, 2nd edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Legrow, Christine and Shirley A. Scott (2018-2022) Saltwater Knitting Books. Portugal Cove-St. Phillip’s: Boulder Books.

May, Vanessa (2013) Connecting Self to Society: Belonging in a Changing World. Baskingstoke: Palgrave.

0 notes

Text

A Sociological Rebel with a Cause:

Remembering Les Samuelson (1953-2022)

By Harley Dickinson and Terry Wotherspoon

Harley Dickinson is Head of the Department of Sociology at the University of Saskatchewan. His specialties are health care, higher education, reflexive modernization, and sociological theory. Awarded a PhD at the University of Lancaster, he is a co-author of the textbooks Health, Illness and Health Care in Canada, and Reading Sociology: A Canadian Perspective. He also published a research monograph based on his doctoral dissertation titled The Two Psychiatries: The Transformation of Psychiatric Work in Saskatchewan 1905-1984. His articles have appeared in Management and Organization Review, Journal of the American Society for Information and Technology, Social Science and Medicine, and in other journals.

Professor Les Samuelson

Terry Wotherspoon, PhD Simon Fraser University, is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Saskatchewan. He is the author of the textbook The Sociology of Education in Canada: Critical Perspectives, and co-author of The Legacy of School for Aboriginal People and First Nations: Race, Class, and Gender Relations. His articles have appeared in Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, Canadian Review of Sociology, British Journal of Sociology of Education, Social Inclusion, and The American Sociologist.

Les Samuelson was a complex character. This in itself, of course, did not make him unique. But he was. We all are complex characters. And like everyone, Les was complex and contradictory in his own way. Although a professional social scientist throughout his professional career, Les was often something of a loner. He never married, he did not have any long-term relationships, and he had no children, though he deeply desired to have all three. He was dedicated to his extended family in Newfoundland.

Most of his colleagues never met most of his family members, although we would occasionally hear about both the distress and strife in which members of his family were entangled, and their accomplishments and achievements. Les’s ruminations on these matters invariably focused on what he could do to alleviate tensions, resolve problems, and aid and support the aspirations of his family members. Over the years, those of his colleagues who knew him realized that at heart he was a deeply caring problem-solver. This was obvious to any who would take time to listen to his musings about his family, but it became increasingly apparent that he also cared deeply about his friends, colleagues, and students, and, of course, they cared about him. In various ways, mostly unintended, however, he made it difficult to get and stay close to him.

Classifying people is notoriously fraught. It is, however, slightly less difficult and risky to identify a dominant personality characteristic or two. A contradictory form of libertarianism was foundational for Les’s identity. His life-long love of motorcycles symbolized this. Indeed, there is a photo of Les standing proudly by his bike in his black leather jacket, looking every bit the tall, dark and handsome rebel without a cause. Despite appearances, however, he did have a cause.

In both his personal and professional life Les’s cause was to look after people. Preparing and sharing food was one way in which he expressed his caring. There are numerous examples. One that stands out revolves around the department’s annual potluck lunch, held at the end of the Fall term between the end of classes and the start of the final exam period. As is the case with potluck meals, people bring a wide variety of things to eat. Les, however, was consistent. Year after year he prepared and brought a roasted turkey with stuffing and side dishes, or a large roast ham. Even on those few occasions when Les was himself unable to attend the lunch, he would prepare the turkey and arrange for a friend to delivery it on schedule for the lunch. It was a large and generous gift of his time and money for which he received, but never sought, gratitude. As we observe later, he also carried his deep and genuine need to care for people into his academic contributions.

Most of Les’s academic career unfolded in a place where he had never expected to stay. He began a term appointment in the Department of Sociology at the University of Saskatchewan in 1988, immediately upon completion of his Ph.D. at the University of Alberta earlier that year. His journey from Newfoundland, after completion of a B.Sc. in Psychology at Memorial University, also included time at the University of Toronto, where he completed an M.A. in Criminology, as well as several motorcycle trips to places between and beyond in the interim. His term position at the U of S led to a tenure-track appointment the following year, and then the award of tenure in due course.

Riding a motorcycle was one of his greatest joys, but it was also the source of misfortune. One beautiful sunny, autumn weekend he was seriously injured in a biking accident. While out riding with a friend south of Saskatoon he was struck by a reckless motorcyclist racing in the wrong lane. Although both riders and their passengers were injured, Les was the most seriously injured and ultimately lost both his legs below the knees.

Despite being on the cusp of life and death, Les bounced back with a new enthusiasm for life. His vow, to be back on his feet before the end of the year, was fulfilled when he demonstrated his prosthetics to visitors who had stopped by in December to give him Christmas greetings. The accident did not dampen his zeal for riding – with both a truck and motorcycle outfitted to accommodate his new condition. In the years following his accident, Les embarked on several more local and cross-country outings. Unfortunately, while riding his motorcycle again in 2022 he was involved in a second accident with a truck. Despite once again vowing to re-engage after release from hospital, he died in hospital as a result of complications related to his injuries.

Les is remembered for several contributions to the scholarship and to the life and work of his colleagues, students, and numerous community partners. His publications, based on research and work in the areas of critical criminology, social control, and relationships between social inequalities and criminal justice systems, appear in several journals and books, including Canadian Public Policy, International Journal of Contemporary Sociology, and Journal of Crime and Justice, and his edited works, Power and Resistance: Critical Thinking About Critical Social Issues (which was regularly updated in several editions) and Criminal Justice: Sentencing Issues and Reforms (co-edited with a former colleague). He also produced several technical reports and presentations for numerous government agencies in Canada and Australia.

Les left an especially impressive legacy through his long-time service towards the decolonization of the academy and the building of bridges between the University of Saskatchewan and Indigenous communities. His commitment in this regard is expressed in what is arguably his most innovative and important academic contribution, namely, the development in 1994 of the Aboriginal Justice and Criminology (ABJAC) degree program, a program that continues to operate (now as the Indigenous Justice and Criminology program). The program, introduced to prepare Indigenous students for careers in corrections, public safety, advocacy, and other areas related to criminal or social justice, was to gain recognition as an exemplary case of Indigenous programing and engagement at the University. Its implementation and success represented a labour of love. It was also pioneering work – work that Les gladly took on largely by himself. When Les conceived of, and decided to build, the ABJAC program there was nothing like it on the University of Saskatchewan campus, nor, for that matter, anywhere else that we are aware of. Although his departmental colleagues at the time understood what he wanted to accomplish, the main form of support they provided was to not get in his way.

Les developed the program in response to concerns that, while Indigenous people as inmates are over-represented in the criminal justice system as inmates, they are under-represented as employees and officials. In developing the ABJAC program he consulted with, and was able to negotiate start-up funding support from government agencies responsible for policing, courts, and corrections. Les designed the program to ensure that students had rigorous training, combining the learning of core skills and knowledge related to sociology and criminology with applied knowledge, skills, and competencies designed to enable students to gain experience working with communities and agencies in relevant fields. Graduates of the program have achieved high levels of success working in many areas, including government agencies, First Nations and Métis organizations, and non-governmental agencies and community organizations in Saskatchewan and further afield.

While this is an especially notable contribution, it is only one of many activities he undertook to work with and support Indigenous students, Elders, and other Indigenous community members in Saskatchewan and Australia. His life and career overall were marked by his consistent dedication and committed service to make the University a welcoming place for everyone, underlined by a focus on justice reform and improved life chances for oppressed and marginalized populations.

Some of his greatest joys were associated with his travels abroad – though limited in number, they took him to Tibet, Australia, and other places. His relationships with Indigenous scholars in Australia was especially prominent in his commitments to decolonization and Indigenous justice at home.

Unfortunately, newer colleagues who did not have an opportunity to meet Les after his initial accident were deprived of the many colourful stories and astute commentaries (some of which made sense) with which he regaled friends and acquaintances alike. However, Les has left a strong legacy for all of us to remember him by.

Les Samuelson has finally returned to his beloved Newfoundland, but sadly not in the manner in which he had planned. Following a celebration of his life, in Saskatoon in October, 2022, his ashes were taken back to St. John’s by family members. It is fitting that Les ended his journey in a place that was always central to his core.

0 notes

Text

Gianfranco Poggi (1934-2023)

By Stephen Harold Riggins

Sociology at Memorial University in the early 1970s had a rather lowly and insecure status. It had been taught at the St. John’s campus since 1956 by a handful of instructors who were young except for retirement-age Nels Anderson, author of the Chicago-School classic The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man. Consequently, an effort was made to bolster the MUN department by hiring a senior sociologist. That effort failed.

Professor Gianfranco Poggi.

The next strategy was so successful that it gave the department an aura among Canadian sociology departments that lasted until the early 1990s. The solution was appointing Visiting Professors. Since the department’s Ph.D. program did not exist then, offering local graduate students short-term teaching contracts was not an option. Department heads at Memorial had the power to make short-term appointments and could hire per-term instructors primarily on the basis of their CVs. To my knowledge, Peter Baehr, formerly of Lingnan University of Hong Kong; and Michael Gardiner, now at Western University of London, Ontario, were the last scholars who benefitted from the department’s commitment to appointing Visiting Professors.

These Visiting Professors, some of whom taught at MUN on two or three occasions, had degrees from prestigious universities: University of Florence, Brandeis University, State University of New York at Buffalo, University of Leicester, University of Warsaw, University of California at Berkeley, University of Essex, University of Bristol, Mining Institute of Leningrad, and the University of Toronto. Most Visiting Professors were relatively young and only later established excellent publication records. The best-known visitor was Zygmunt Bauman. He was retired when he came to MUN but was not yet a celebrity.

“What made the MUN department exciting,” Volker Meja told me, “was the people passing through. At large universities such visits happen naturally. Due to the location of St. John’s we had to make a special effort to attract prominent scholars. This really worked for over ten years. It drew people together intellectually.”

Gianfranco Poggi was one of the visitors. Meja met Poggi at the World Congress of Sociology in Madrid in the summer of 1978. He invited Poggi to give a lecture or seminar in St. John’s at a time of his choosing. It was then common for sociologists and anthropologists to give public presentations in the Great Hall at Queen’s College, the building where the department was located. Poggi was overcommitted when first invited, but did teach at MUN in the summers of 1980 and 1982 as well as the autumn of 1983. Poggi was an authority on sociological theory, especially the classics of the 19th and early-20th centuries; the development of the modern state; and political power. If you have never read Poggi, a good place to start might be his little book Weber: A Short Introduction or the book co-authored with Giuseppe Sciortino Great Minds: Encounters with Social Theory.

Poggi (1984) wrote a memoir about his early experiences, which he titled “The Wopscot Chronicle: Reflections of a Half-baked Sociologist.” The title is a pun on The Wapshot Chronicle, a novel by John Cheever. “Wop” is an insulting slang term for Italian; Poggi was then living in Scotland. He was born in spectacularly beautiful Modena, Italy. It should not be a surprise that his first degree was in law when his father was a judge and in the 1950s sociology had not yet been reestablished in Italy following the catastrophe of Fascism. Poggi was attracted by what he learned about American society at the U.S. Information Service library in Bologna. Browsing among the sociology books in this library, he began to form an idea of sociology as a discipline. Sociology seemed like a distinctly American subject, which also made it appealing to him. When he applied for graduate school in the US in 1956, he still knew little about the discipline. The University of California at Berkeley was not his first choice. Some bureaucrat decided to send him there. After a while, he realized that he had been very lucky. His dissertation, published by Stanford University Press, was about social activism by Italian Catholics.

Poggi’s first full-time teaching position was at the University of Edinburgh where he remained for 24 years but during those years often taught on short-term contracts in North America and Australia. Beginning in 1988, he taught for several years at the University of Virginia before returning to Italy where he was affiliated with the European University Institute in Fiesole and the University of Trento. It could be argued that Poggi’s research contributed to the revival of sociology in Italy after World War II, although he adamantly downplayed his role in this development.

“I am reminded of [David] Riesman’s remark,” Poggi wrote, “that there are two kinds of sociologists, those interested in sociology and those interested in society. My problem is that I would like to be one of the latter, but if I am any good at all it is as one of the former. …I am not a natural sociologist, a shrewd observer and interpreter of social facts-on-the ground. …[I prefer] instead to think of another writing project which I can handle by reading other people’s books” (The Wopscot Chronicle).

A letter to Meja (September 17, 1980) also gives some insight into his status among well-known professional sociologists and into his personality. He had recently contacted Daniel Bell, author of The End of Ideology and The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. “He received me in his home and said he could only give me twenty minutes because his eye was bothering him – but then kept me there for nearly two hours, talking (quite entertainingly, I must say) almost all the time.” Poggi also mentioned that he had chats with German sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Poggi’s presentation at the 1980 annual meeting of the American Sociological Association was “quite well received” even by the “Redoubtable Niklas himself.” Poggi certainly name drops in his letters, and indeed the references are to well-established sociologists, but he does this in a way which is not offensive.

In another letter to Meja (January 2, 1986), Poggi expressed interest in returning to MUN for a fourth visit and writing for a sustained period of time with Victor Zaslavsky. Poggi’s daughter, Maria Johnson, professor of religious studies at the University of Scranton, confirmed to me that her father enjoyed living in Newfoundland. Perhaps it is not insignificant to mention that he displayed Volker Meja’s photographs of Newfoundland icebergs in the family’s Edinburgh home.

Scottish sociologist David McCrone, who taught as a Visiting Professor at MUN, wrote in Scottish Affairs (vol. 32, no. 4) that Poggi was an intellectual tour de force with Italian boyish charm. Giuseppe Sciortino, in his obituary for Poggi in the magazine il Mulino (The Mill) commented: “His intellectual output is also a magnificent example of passion without pettiness. …If he continued to deal with other authors forgotten by many, it was not out of inertia. They were thoughtful choices, which did not need controversy and tactical positioning to be taken calmly and communicated transparently.”

Major Publications by Gianfranco Poggi

Poggi, Gianfranco (1967) Catholic Action in Italy: The Sociology of a Sponsored Organization.Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

-- (1972) Images of Society: Essays on the Sociological Theories of Tocqueville, Marx and Durkheim. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

-- (1978) The Development of the Modern State: A Sociological Introduction. London: Hutchinson.

-- (1983) Calvinism and the Capitalist Spirit: Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

-- (1990) The State: Its Nature, Development, and Prospects. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

-- (1993) Money and the Modern Mind: Georg Simmel’s Philosophy of Money. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

-- (2000) Durkheim. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

-- (2001) Forms of Power. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

-- (2003) “Tom Burns 1913-2001,” Proceedings of the

British Academy, 120, 43-62.

-- (2006) Weber: A Short Introduction. Cambridge, UK:

Polity Press.

-- (2014) Varieties of Political Experience; Power Phenomena in Modern Society. Colchester, UK: ECPR Press.

Gianfranco Poggi and Giuseppe Sciortino (2011) Great Minds: Encounters with Social Theory. Stanford, CA: University of Stanford Press.

0 notes

Text

Newfoundland style mittens knitted by Lynda Harling Stalker.

0 notes

Text

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 23

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 22

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 21

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 20

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 19

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 18

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 17

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 16

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 15

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 14

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 13

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 12

Sociology on the Rock, Issue 11

Sociology on the Rock ARCHIVE

0 notes

Text

Editor and Founder: Stephen Harold Riggins

Webmaster: Zbigniew Roguszka

Issue 23 in PDF

0 notes

Text

This issue

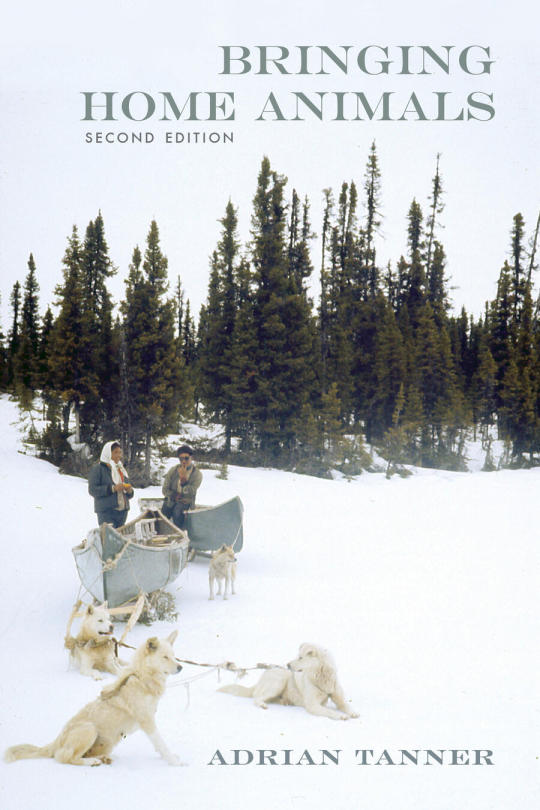

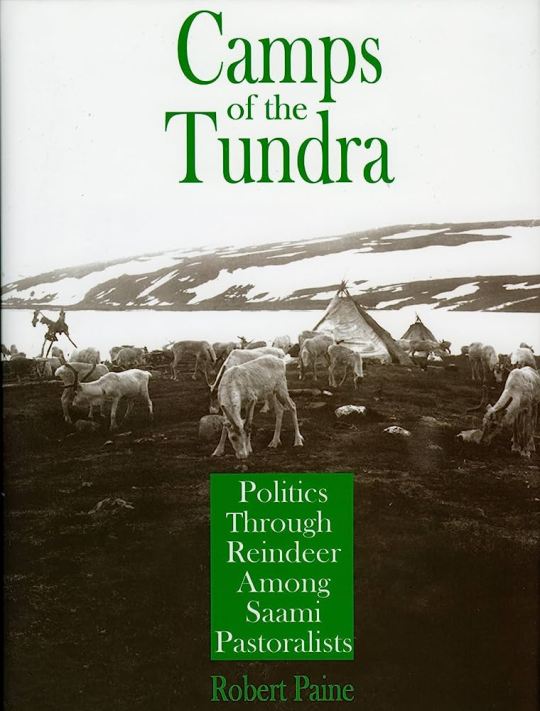

Adrian Tanner: Remembering Social Anthropologist Robert Paine.

Stephen Harold Riggins: Which Memorial University Sociologist will be read in a Hundred Years?

Chris William Martin: Fatherhood is an Act of Letting Go.

Shayan Morshedi: Why do some Violent Events stick in our Collective Memory while others Fade Away?

0 notes

Text

“Humans weren’t created from scratch, and anyone who is seriously interested in how our minds work simply must have some appreciation for both the logic of evolutionary theory and the rich body of data on the mental lives of other animals” – Paul Bloom.

0 notes

Text

Memorial University graduate students who participated in the 2023 annual meeting of the Canadian Sociological Association at York University. From left to right: Forough Mohammadi, Adela Kabiri, Heather Dicks, Atinuke Tiamiyu, Hannah Marie-Laure McLean, and behind them are Shayan Morshedi and Pouya Morshedi.

0 notes

Text

Remembering Social Anthropologist Robert Paine

By Adrian Tanner

Crossing Boundaries

When social anthropologist Robert Paine came to Memorial in the mid-1960s and headed the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, he faced significant barriers to building a strong academic unit. As the only university in the province, and a relatively small one, the administration had to try its best to cover all the bases in undergraduate course offerings. The salaries Memorial offered were generally below those of mainland universities. In the social sciences and humanities, scholars generally select their own research, often as individuals, and bring to it and to their teaching, their own interests, experiences and conceptual approaches. Moving a department in a particular direction is like herding cats. Robert brought in a very diverse group of scholars, and never tried to create anything like a school of the followers of his own ideas.

Robert brought in as ISER Fellows many anthropologically trained scholars to conduct the kind of research that elsewhere in North America is known as “rural sociology.” To recruit new scholars he tended to use his existing personal networks. However, I wonder if it is the case, as has been suggested, that he actively discouraged sociology. The sociologist, Nels Anderson, who was a member of the Sociology and Anthropology Department between 1964 and 1966, is quoted as saying of Robert, “He knows nothing about sociology so he puts anthropology up and sociology down, so the best for me is to stay at the typewriter, see and hear but say nothing” (Riggins 2017:104).

It is true that Paine was skeptical of how statistics can be misused, such as in his comments on those Norwegian scholars who had cited figures on the size of Sami caribou herds, but without considering the herd’s age profile, which fundamentally misrepresented the situation (Paine 1986). Nels Anderson had no previous experience as a full-time faculty member in a university, and thus had little familiarity with the way academic departments operate. Robert also knew as little about archaeology as he did about sociology, and yet this specialization was able to get established under his headship. Robert would have had a hand in recruiting Jim Tuck; and after his arrival, Tuck was able to bring in other archaeologists, and develop a very successful unit within the department. Was it indeed the case that Robert prevented the same kind of development from taking place among the sociologists within the department?

While visiting Toronto in 1972, Robert Paine, about whose academic work I was only vaguely aware, invited me to apply to Memorial. My first impression of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology was of a small but interesting and diverse group of scholars, Robert Paine’s influence was evident, although mainly indirectly, from his role as director of ISER and ISER Books, and from the various scholars, many from Scandinavia, who he had invited to conduct research in this province. He was no longer the department head, and did not come to department meetings. He was rumoured to have good relations with Memorial’s senior administrators, particularly with President Moses Morgan; and the Dean of Arts and later Vice-President (Academic) Leslie Harris. It was relatively simple in those days for department members to get funds from ISER for small projects.

I was pleased to find how well department members generally got along together, as I had previously encountered some vicious internal factional conflicts among faculty members in the Anthology Departments at both McGill and the University of Toronto. We also felt privileged having the benefit of Robert’s influence with the administration, and our preferential connection to ISER, even if this was only of direct relevance to those doing research in the province. However, Robert’s influence with the administration had not extended to one of the most persistent issues faced by all university departments – space. The department seemed to be treated as somewhat peripheral within the Arts Faculty, compared, for example, to better established departments, like English or History, in that our offices were relegated to a temporary building until we moved to Queen’s College. Moreover, in the decades since then Memorial has never managed to house all the social sciences in the same building.

The split with sociology, a year after I arrived, was, as far as I was made aware at the time, imposed by the university administration. I was told the reason was that there was a problem among the sociologists, and that they needed to be isolated as a group in order for the issue to be fixed. Academically the sociologists formed a separate group within the department, as did the archaeologists, and it was not clear to me why this arrangement seemed to be working for the one but not for the other. At the time, I assumed this “problem” was that the sociologists lacked a senior sociologist with leadership skills. I have recently learned that, while the initiative for the split came from the Dean of Arts a couple of years before my arrival, the matter had been debated within the department, with a division of opinion on the issue among department members, including some anthropologists arguing in favour of the split.

Knowing none of this, on arrival I felt comfortable to be in a joint Sociology-Anthropology Department, even if it was more common for universities to have separate departments. While anthropologists had once focused exclusively on tribal societies, with sociology studying “modern” industrial ones, a shift was well under way by the 1970s. Anthropologists had begun focusing on “communities” in general, in both industrial and tribal contexts, often using participant observation, while sociologists remained mainly concerned with mass society, often using surveys and statistical methods. My first academic friendships, initially within the department, were with people like Jean Briggs, Ron Schwartz, Judy Adler, Volker Meja, Barbara Neis and Doug House. While all but Jean were sociologists, I did not feel any disciplinary boundary between us in our academic work or our intellectual ideas. For example, I found that Meja’s work on the sociology of knowledge was in principle applicable to the kinds of small-scale societies that I studied. For me, the two disciplines are complementary approaches. My general attitude is that, while disciplines may be an organizational necessity for a university, and for those professions that make practical use of university research, the disciplinary silos that academic departments sometimes create can be a barrier to good scientific thinking, and to new discoveries. I believe in a holistic, unified social science.

Friend and Scholar

After the split, the Anthropology Department began to assert itself with what seemed to me a new emphasis stemming from the department’s autonomy, that is, a general unwillingness to go along meekly with whatever dictates or suggestions might come down from the university administration. However, given that Gordon Inglis, John Kennedy and I were the last new anthropology hires for a few years, there was little opportunity to change the department’s direction after the split. Beginning in 1971, John Kennedy had been an ISER Fellow, specializing in coastal Labrador communities, and was appointed to the department in 1973. Gordon Inglis was hired in the department in 1972 to head a new community development program. Robert must have been aware of the new management style that Anthropology adopted, but I do not know what he thought about it.

Although in later years, Robert and I became friends, in those early days I did not see a whole lot of him. I was closer with Jean Briggs, who like me had conducted long-term participant observation research with hunters, in her case with Inuit, and in mine with Cree. Jean also had an on-and-off friendship with Robert. Jean had been involved in Robert’s Killam team project, “Identity and Modernity in the East Arctic,” which was winding up when I arrived, although The White Arctic (Paine 1977), a major collection of articles from the project, was published a few years later. I became aware of the innovative direction this project had taken from some of the ISER fellows who were, or had been, members of the project team, like John Kennedy, Ditte Koster and Hugh Brody. John Kennedy had contributed a chapter in The White Arctic on ethnic division in one northern Labrador community. Ditte Koster had written a chapter on gossip among non-Inuit in an arctic community. By the 1970s, when I knew her, she was working as a Memorial University librarian, and writing her doctoral thesis on the federal Department of Indian Affairs, which took her into the literature on bureaucracy, very much a part of sociology. She died from cancer in 1981, before that work could be completed. Hugh Brody is now a famous writer and film maker. He studied anthropology at Oxford, and had conducted research in Ireland, after which he lived in a number of Canadian arctic communities, on the basis of which he published The People’s Land (Brody 1975), as well as a chapter in The White Arctic.

Paine’s project was remarkable in two ways. It was the first team research project to focus on the role that non-Inuit were playing in the lives of the Inuit, something I was already personally aware of from my own experience living for three years in the arctic, before becoming an anthropologist. Secondly, in the publications that came from the project Robert introduced to a North American context several of the theoretical concepts developed earlier by the Norwegian scholar Frederick Barth.

Barth had studied at Oxford, and Robert had known him personally when Barth was heading the Anthropology Department at the University of Bergen in Norway. I was already aware of Barth from his often-cited research Ethnic Groups and Boundaries (1969). In terms of his general theoretical approach, with which Robert identified, Barth is known as a “transactionalist.” Barth described this as follows: “Most of our basic relationships, all of our basic relationships, are social relations that are built around mutual transactions” built upon the “biological constraints of ecology” (Anderson 2007, p. xii). Like most of the concepts used by Robert Paine in his work, such as brokers and patrons, gossip, and political rhetoric, these ideas are as relevant to sociology as they are to anthropology.

Robert did contact me from time to time in those early years, and showed interest in my work with the Cree, particularly on the impact of the James Bay hydro-electric project, as well as on the land claim of the Labrador Innu. After only two years at Memorial I asked for, and was given, a semester off, so I could temporarily move to Montreal to set up a negotiating team for the Naskapi of Quebec in land claims negotiations. This particular First Nation had, up to then, been left out of the James Bay Agreement negotiations, even though under the agreement they were about to lose aboriginal title to their traditional lands. It was therefore urgent that they immediately got involved in the negotiations. Robert came to visit me in Montreal while I was working for the Naskapi, and showed a lot of interest in the issues I was facing. This was some years before Paine himself took on an advocacy role alongside the Sami, in their opposition to the Kautokeino hydro scheme in northern Norway (Paine 1982).

After coming to Memorial, I paid a bit more attention to Robert’s research, particularly on the Sami, noting similarities, despite the forager/herder divide, between the Cree hunters I worked with and Robert’s reindeer herders. Both were nomads in similar subarctic environments, with similar material cultures, but with quite different idea systems. However, over the next forty-plus years Robert and I never did formally collaborate on research, although we regularly swapped ideas, news, and stories about our mutual field work experiences. We also kept a close interest in each other’s research projects.

I noticed how Robert turned on the charm with most people he dealt with, including strangers. However, some women, in particular, found him patronizing or condescending, if their work was not of interest to him. In time, Robert and I began to have lunch together on a regular basis. We ate at restaurants, and he always chatted up the server, and usually managed to get the person to talk about themselves. I could see that he was a natural as an ethnographic field worker.

Over time, Robert and I occasionally exchanged drafts of papers for comments. Some people thought that Robert sometimes used other people, but I felt I got as much from my relationship with him as I gave. Robert always came to department seminars, and tended to ask questions that often took the discussion in a new direction. I confess that I sometimes had difficulty following some of these “off-the-cuff” ideas, and, apart from concepts like “welfare colonialism” a phrase he coined to describe government relations with the Inuit, I cannot say that his ideas had a significant influence on my own writing or intellectual development, at least not consciously. Robert also gave seminars, and this kind of forum seemed to be one he enjoyed.

Moreover, Robert and I got along well despite, and not because of, our similar social backgrounds and the circumstances of our UK origins. For instance, both of our fathers had officer-level military backgrounds. I had come to Canada in part as a rejection of the British class system that I had grown up in, and my parents’ views on social class and politics. It seemed to me that Robert, while not a snob, embraced, rather than rejected, his British class status. One factor behind this, apart from his years at Oxford, could have been that while I had come to Canada as a teenager, Robert moved here in his late 30s.

My wife, Marguerite MacKenzie, and I were invited to Robert’s house from time to time, as well as having him to our place. I got to know all of his various wives, except for his first, Norwegian one, although he would often talk about their son, Michael. When I first knew Robert, he was living in a house in the woods on Old Broad Cove Road, on the outskirts of Portugal Cove, with his second wife, Sonja. Among her other talents, Sonja was a flamenco dancer, and gave occasional public performances in St. John’s.

Sonja was also employed as a text editor for ISER Books, and in my dealings with her I found that she held very strong opinions. I felt that, as the wife of the Institute director, she put some authors whose work she edited in an awkward position. This issue once gave me difficulties, when I edited an ISER book The Politics of Indianness (Tanner 1983). Robert had come to me with three studies that had been submitted to ISER Books, none of them enough to make a book on its own. I took the editing task as a challenge, despite initial misgivings, and in the end I was pleased that I had been able to set down in print some of my own ideas about Indigenous politics in Canada in my introduction. However, I lost at least one battle with Sonja over the text, and later became aware that one of the authors in my collection was very unhappy with a change she had made.

Robert also moved house quite often – after Portugal Cove he had a house on Bond Street, in the old part of the city, and later another in an upscale area off Kings Bridge Road. For a while he lived in Ottawa. His last house was at the East end of Empire Avenue, with a garden that stretched down to Rennies River. This last house was close to Quidi Vidi Lake, where Robert would often walk. He was something of an expert on sea birds, at least from my perspective, knowing nothing on that subject. Robert told me he had been brought up in Exeter, in Devon, and as a youth had spent time on the large estuary of the River Ex, where he became familiar with its bird life. I have since got to know this area myself, after one of my brothers retired to the same general area.

Given that when he came to Memorial, the Department of Sociology and Anthropology was a small unit in a small university in an out-of-the-way place, it is remarkable that Robert Paine managed to create a department that punched above its weight, and made a distinctive contribution to the development of the social sciences in Canada. He and I remained friends to the end, with me visiting him on his death bed. Today, he is one of those deceased acquaintances who I can truly say I miss.

Adrian Tanner is Professor Emeritus in the MUN Department of Anthropology. His publications include Bringing Home Animals and The Politics of Indianness: Case Studies of Native Ethnopolitics in Canada.

Robert Paine photographed by Moyra Buchan

References

Anderson, Robert. 2007. Interview with Fredrik Barth – Oslo, 5 June 2005. AIBR, 2(2), xii. Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana (AIBR). www.aibr.org, 2(2), 2007, i-xvi. Madrid: Antropólogos Iberoamericanos en Red.

Barth, Frederick.1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Bergen: Universitetsforlaget, and London: Allen & Unwin.

Brody, Hugh. 1975. The People’s Land. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre; and New York: Penguin, 1977.

Paine, Robert (Ed.). 1977. The White Arctic: Anthropological Essays on Tutelage and Ethnicity. St John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Paine, Robert. 1982. Dam a River, Damn a People. Copenhagen: International Working Group for Indigenous Affaires.

Paine, Robert. 1986. Interview with Robert Paine by Piers Vitebski. Youtube - www. youtube.com > watch?y=luAyT4a-nfA. Accessed October 29, 2022.

Riggins, Stephen Harold. 2017. “Sociology by Anthropologists: A Chapter in the History of an Academic Discipline in Newfoundland during the 1960s,” Acadiensis, 46(2), 119-142.

Tanner, Adrian (Ed.).1983. The Politics of Indianness: Case Studies in Native Ethnopolitics. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research.

0 notes

Text

Which Memorial University Sociologist will be read in a Hundred Years?

By Stephen Harold Riggins

If I were to name a Memorial University sociologist who might be read in a hundred years, Victor Zaslavsky (1937-2009) would certainly be at the top of the list. Zaslavsky is important despite – perhaps because – his initial training was not in the social sciences. He was a mining engineer who became an art historian, a critic of organized brutality, and an author of autobiographical short stories.

Zaslavsky’s parents were “Old Bolsheviks,” supporters of communism before the Russian Revolution, who survived Stalin’s purges by abandoning politics. Victor helped his father, a metallurgist and chemist, burn letters from Trotsky in a fireplace. His mother, a physician, was director of a hospital during the 900-day Nazi blockade of Leningrad. Like many children, Victor had been evacuated from Leningrad with his aunt to the distant Urals, while his mother stayed behind. The experience is described in his autobiographical story “Nadezhda.” An English translation was published by Judith Adler in 2022 in the journal Society.

As a young man, he was interested in history, although the discipline was too political, and he was rejected by Leningrad State University because of anti-Semitism and nationality quotas. It was difficult for Jews, even assimilated agnostics, to win acceptance to the most popular Russian universities. They solved the problem, like Zaslavsky, by majoring in a subject most young people did not want to study. Consequently, Zaslavsky was educated at the Leningrad Mining Institute, the oldest mining school in Russia. From 1959 to 1968, he was employed as a mining engineer, working in distant regions before gaining permission to attend evening courses in art history and aesthetics at the Krupskaya Institute of Cultural Studies. He spent several years at the Krupskaya Institute, becoming a lecturer in 1972 and was allowed to travel to East Germany to complete his research for a dissertation titled The Problem of the Aesthetic Relation in Soviet Aesthetics (1954-1974) that he would never get to defend. He started at the Krupskaya Institute in 1969 and would have defended his dissertation in 1974, had his nephew not emigrated in 1973. He also did lectures on art history as an adjunct, including at the ballet school, to make some money on the side.

Outside the classroom, Zaslavsky seems to have been reticent about recounting his personal experiences in the Soviet Union. Perhaps he was tired of the topic or thought Canadians would not understand. He was less reticent among Russian immigrants. I quote Vladislav Zubok, whose recollections appeared in a book of eulogies for Zaslavsky. As a young geologist, Zaslavsky crisscrossed the Soviet Union. One of his instructors was a Chechen veteran of World War II, an expert in explosions. The story is that the instructor was punished for refusing to blow up a famous Leningrad cathedral. “Zaslavsky said to me once,” Vladislav Zubok wrote, “pointing to a building across the street, ‘I could blow up that building over there so that all window-panes on this side of the street would remain intact.’ I thought he was joking, but understood that he knew indeed how to do it” (Zubok, in Orlandi, 2010: 163). This is also described in his autobiographical story “The Professor of Explosion,” published in German translation.

It was not Zaslavsky’s intention to leave the Soviet Union (Riggins interview 2007). He said on several occasions that the Soviet system was not as rigid as it looked. His family was ostracized when a nephew, his sister’s son, immigrated to Canada in 1973. His sister, her husband, and Zaslavsky himself were blacklisted for “political unreliability.” He had participated in activities, which were “unofficial” although not subversive. The final straw was that he was told his son Alexander, age 10, would never be allowed to attend university. Zaslavsky reluctantly joined the exodus of 250,000 Jews who left the Soviet Union in the mid-1970s. In 1973, when nephew Serge emigrated, the numbers were small and receiving permission was far from guaranteed, hence the old joke that you would be going “either West or East” (meaning Siberia); by 1974 and 1975 the floodgates opened, only to be shut again in 1980.