A thing of many names. Pronouns are mainly ce/cer and it/its (IT/ITs for fun, they/them auxiliary). Icon is IC 2220, header image is the Apollo 8 Earthrise photo. blogging from a comet ☄️“You are going to have to believe that I love you. Most often in the absence of concrete proof.”

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

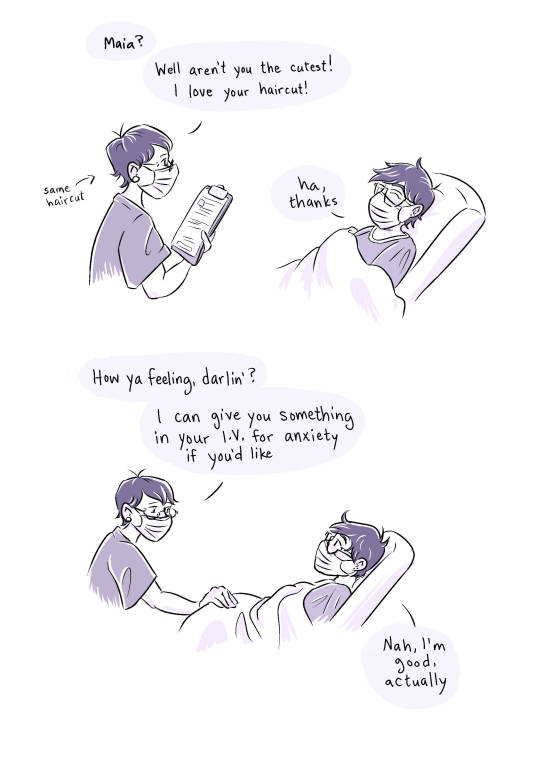

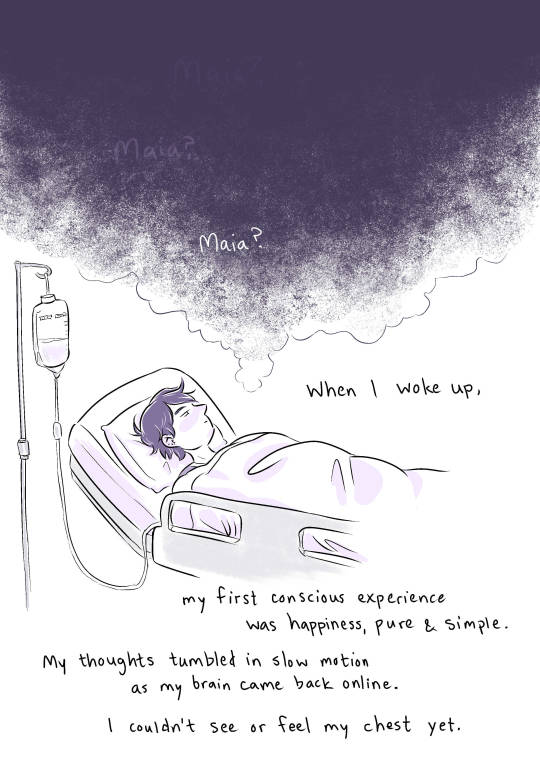

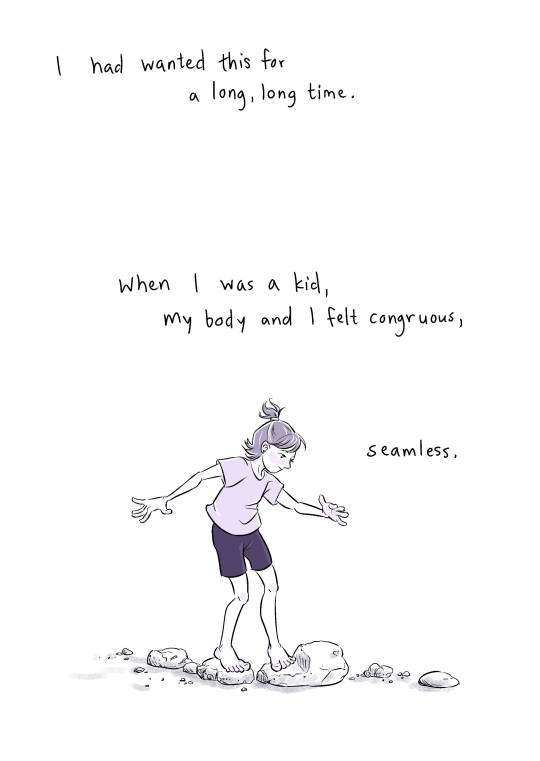

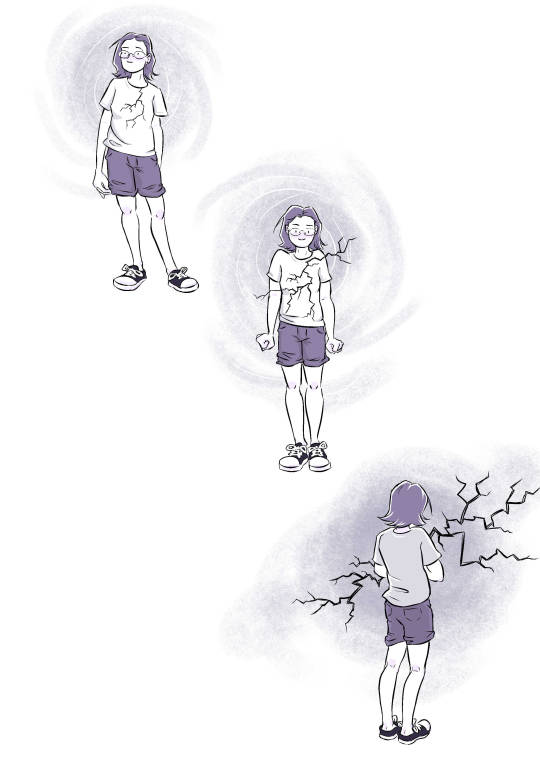

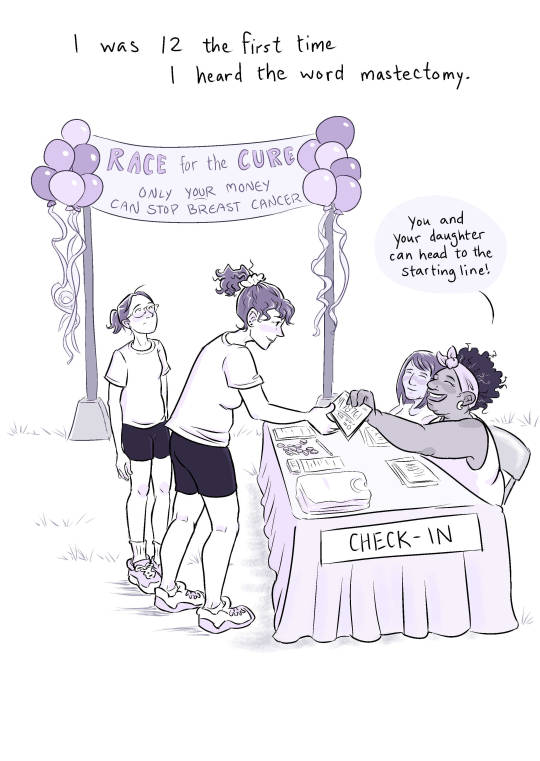

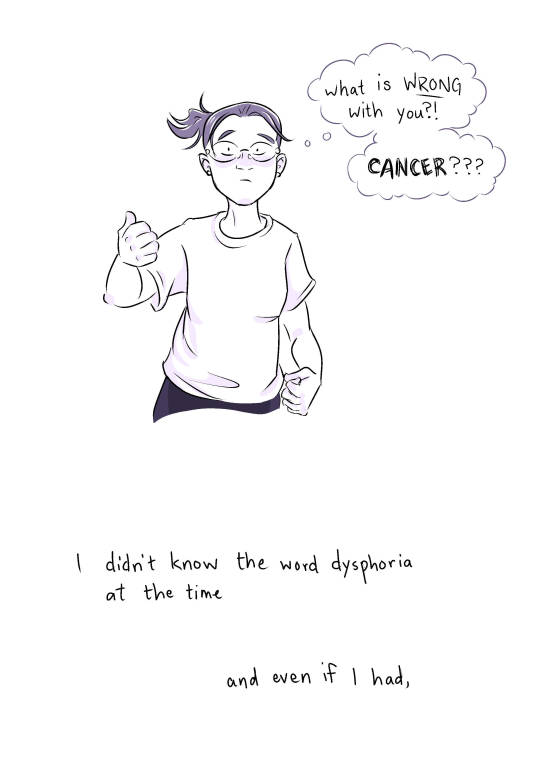

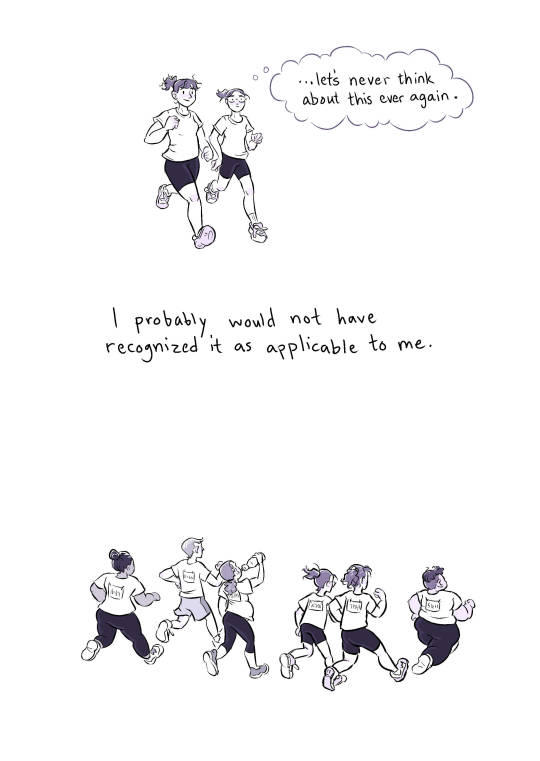

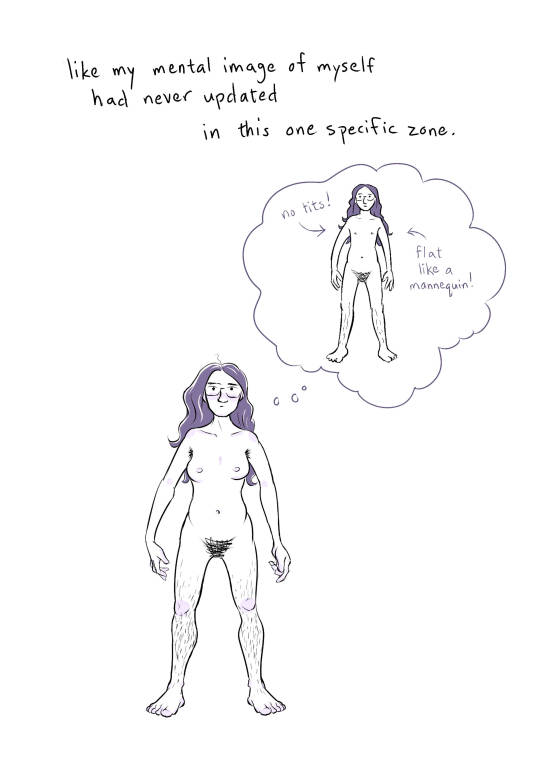

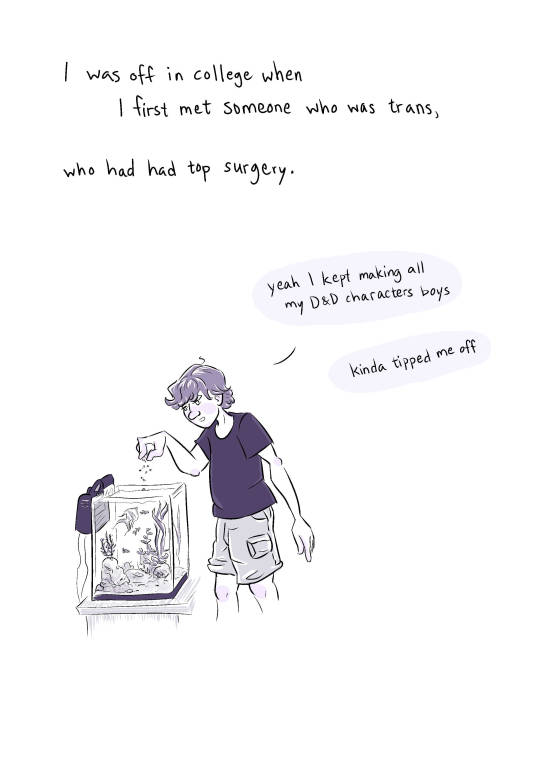

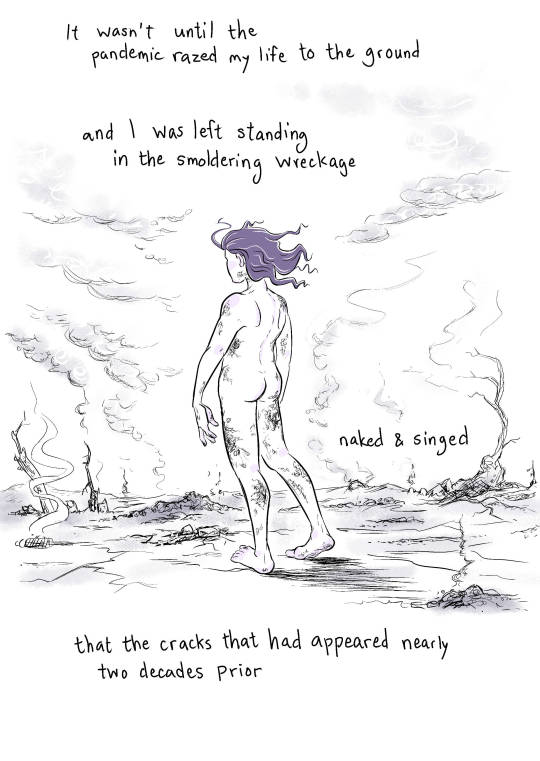

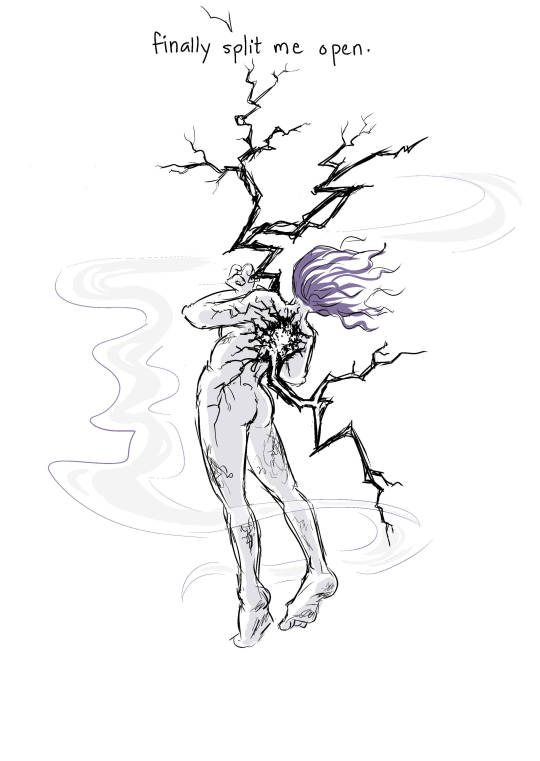

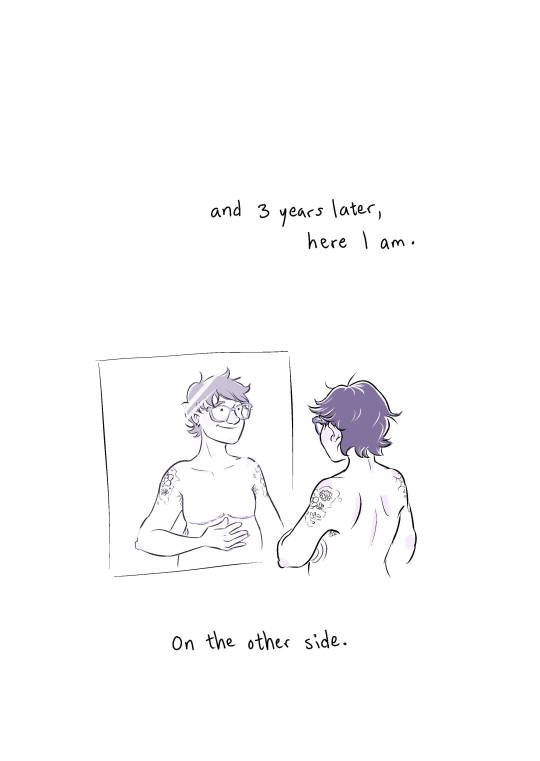

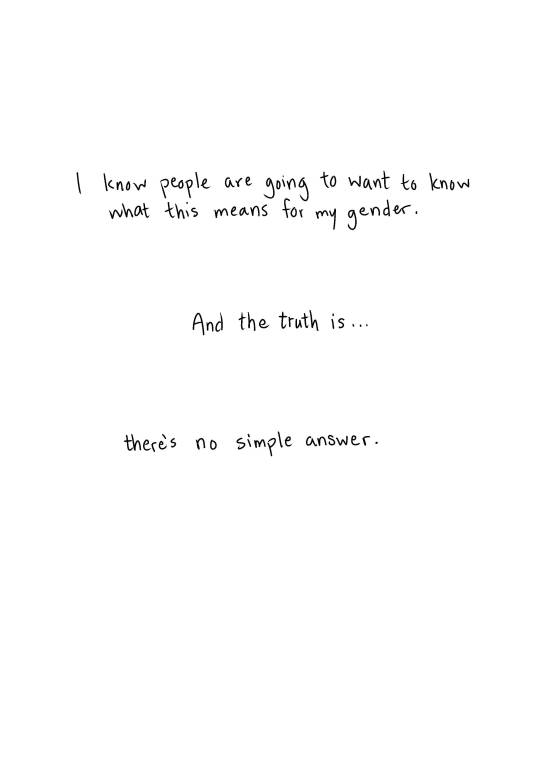

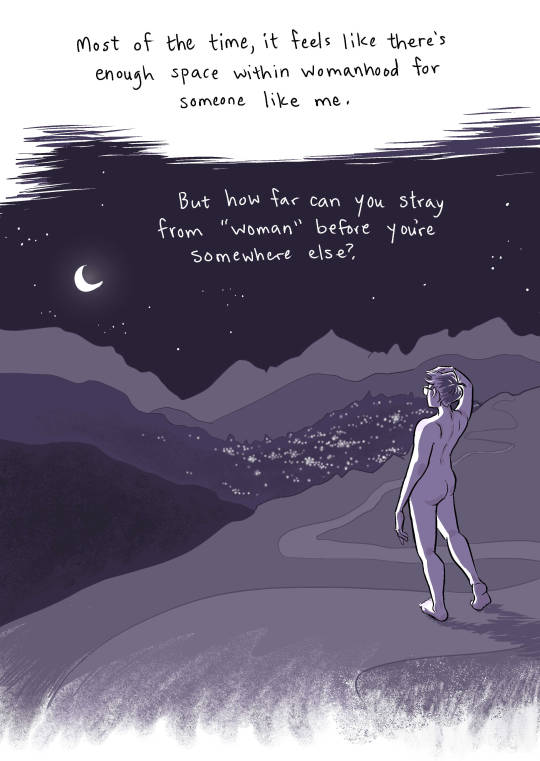

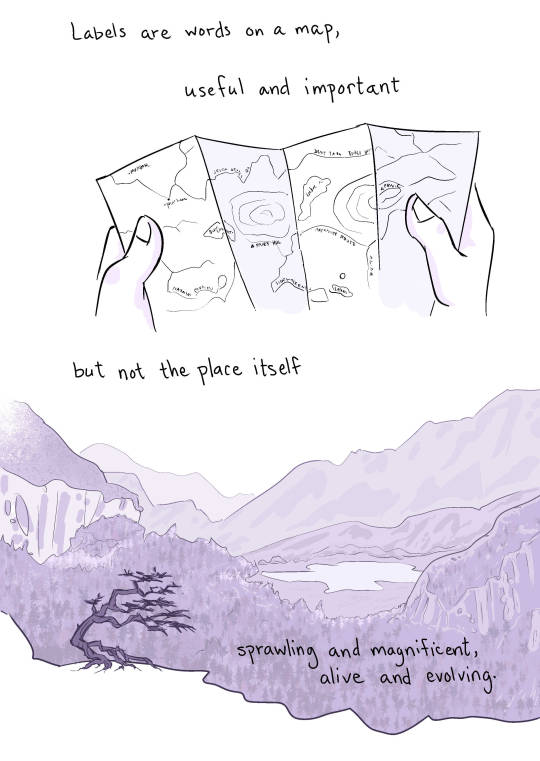

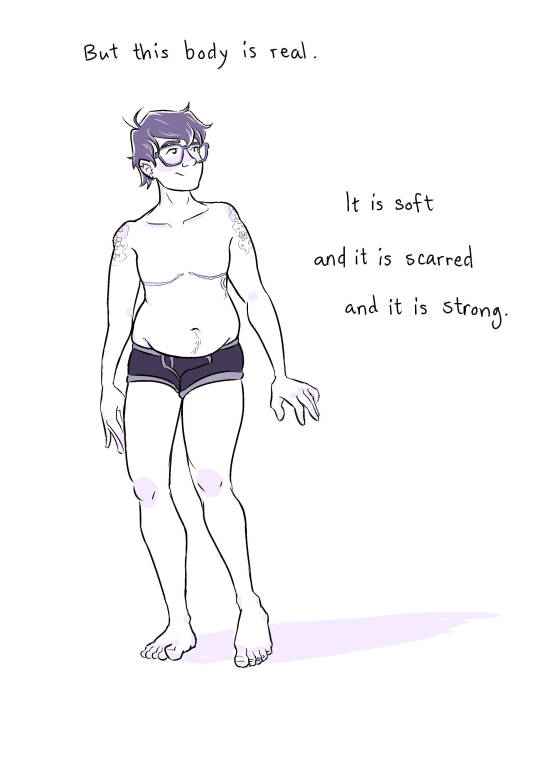

yes I'm now on the other side of top surgery and I'm allowed to lift things again 💪 You might have already seen this one on my substack -- did u know you can subscribe to my substack for early access to comics like this?! Sent directly to your email inbox??? FOR FREE????? (there is also an optional paid tier for exclusive bonus content for five bucks a month but like 80% of my posts will be free and publicly available) ty ily♥

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

I do wish that "oppositional sexism" was a more commonly known term. It was coined as part of transmisogyny theory, and is defined as the belief that men and women, are distinct, non-overlapping categories that do not share any traits. If gender was a venn diagram, people who believe in oppositional sexism think that "men" and "women" are separate circles that never touch.

The reason I think that it's a useful term is that it helps a lot with articulating exactly why a lot of transphobic people will call a cis man a girl for wearing nail polish, then turn around and call a trans woman a man. Both of those are enforcement of man and woman as non-overlapping social categories. It's also a huge part of homophobia, with many homophobes considering gay people to no longer really belong to their gender because they aren't performing it to their satisfaction.

It's a large part of the reason behind arguments that men and women can't understand each other or be friends, and/or that either men or women are monoliths. If men and women have nothing in common at all, it would be difficult for them to understand each other, and if all men are alike or all women are alike, then it makes sense to treat them all the same. Enforcing this rift is particularly miserable for women and men in close relationships with each other, but is often continued on the basis that "If I'm not a real man/woman, they won't love me anymore."

One common "progressive" form of oppositional sexism is an idea often put as the "divine feminine", that women are special in a way that men will never understand. It's meant to uplift women, but does so in ways that reinforce the idea that men and women are fundamentally different in ways that can never be reconciled or transcended. There's a reason this rhetoric is hugely popular among both tradwifes and radical feminists. It argues that there is something about women that men will never have or know, which is appealing when you are trying to define womanhood in a way that means no man is or ever has been a part of it.

You'll notice that nonbinary people are sharply excluded from the definition. This doesn't mean it doesn't apply to them, it means that oppositional sexism doesn't believe nonbinary people of any kind exist. It's especially rough on multigender people who are both men and women, because the whole idea of it is that men and women are two circles that don't overlap. The idea of them overlapping in one person is fundamentally rejected.

I think it's a very useful term for talking about a lot of the problems that a lot of queer people face when it comes to trying to carve out a place for ourselves in a society that views any deviation from rigid, binary categories as a failure to perform them correctly.

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

You know what I've never really seen realistically depicted in fiction? The way that people in places that get a huge amount of snow deal with said snow. Specifically in the cities. I get that it's probably not exactly an intuitive thing to think about if you've never lived in a place that gets a lot of snow, and even if you do, you probably figure that they must have some really sophisticated infrastructure systems specifically for this purpose. It's not like they'll just scoop the snow off the streets and gather it into huge piles, and then just climb over the progressively larger and larger snow piles every single year for months while waiting for the piles to melt in the spring.

We do. There's no point in planning more sophisticated systems to get rid of something that'll eventually just go away on its own. So they just pile the snow into randomly designated spaces that cars or people aren't supposed to go through, and let it pile up. There's significantly less street parking available in the winter because some spots where you could otherwise park a car are currently the parking spot of a snow pile three times taller than a car.

You get used to it. And if you grow up around here, it never even occurs to you to think of it as something strange in the first place.

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

Spin this wheel first and then this wheel second to generate the title of a YA fantasy novel!

(If the second wheel lands on an option ending with a plus sign, spin it again)

Share what you got!

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

openin’ the door to the microwave one second early because you don’t need all the hootin’ and hollerin’

78K notes

·

View notes

Text

it pisses me off SO bad how transphobes have so effectively used sports to launder transphobia and misogyny to people. like does nobody remember like ~5-10 years ago when it was a MAJOR feminist talking point to argue for desegregating sports and going by skill level instead of gender separation??? and now, because so many cis people hate trans people so violently and think we should be excluded from all aspects of public life, you’ve got a whole bunch of women who call themselves feminists laundering misogynistic talking points about how “women are just inherently weaker and worse at athletics than men :(( it’s just biology and women are inherently inferior :(( this is definitely not misogyny that’s unsupported by science, women are just weaker and worse at things :((“ like girl open your ears and listen to what you’re saying!!

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

daily affirmations:

i am kind

i am in control of my emotions

it does not bother me when someone is in the kitchen while i was planning to be in there alone

everyone in the house has the right to be in the kitchen

i am kind and in control of my emotions even when someone is in the kitchen while i was planning to be in there alone

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the things that makes autism a disability (and why some of us choose to label it as such rather than an “alternate neurotype”) is the stress.

part of autism is just being incredibly stressed. overstimulation? stress. holding a conversation? stress. something happening to our schedule? stress. people talk about how often autism is recognized and diagnosed via our stress responses (like meltdowns) because it is just so common to see autistic people stressed because of lack of accommodations to how our brains work.

and this matters because stress kills. stress causes a lot of health issues, or it can trigger pre-existing ones by making certain chronic conditions flare up. i once had a psychiatrist very unhelpfully tell me i “just need to manage my stress” when the stress i was describing was things i could not avoid in neurotypical society and can’t “just get over”. i can do “self care” all i like but i cannot at the very base level change the way my brain inputs information and reacts accordingly.

#“manage your stress” i am stressed by things i literally cannot avoid by existing in this world#not to mention that constant stress is EXTREMELY detrimental to your health and can make other conditions you might have worse#autism stuff

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

new cover dropped

#was expecting the star thing to look more like a telescope but it’s still a fun design!!#i will always be in favor of more astronomy stuff of course :)#kotlc

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

you ever think about how fucked up the phrase "commit suicide" is

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tell me which kotlc characters you hc as genderqueer/non-binary I need it for a thing I'm making

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes it is very funny that Keefe wore a Taylor Swift shirt without knowing what it was, but also, one must admit that if and when he finds out, Keefe would absolutely be a swiftie

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Quick reminder since apparently it bears reminding in both directions: if bigoted people, closed-minded people overall, or your own internalized insecurities misinterpret a queer person’s message in a way that hurts/endangers you, yeah, it sucks, but it’s not the fault of the queer person in question, nor should it be a reason for them to silence themselves. They’re probably as hurt/pissed as you are that someone misinterpreted and misused their message to do harm.

Of course sadly there’ll still be queer people that actually DO mean harm and dismissal to other queer people – I ain’t speaking for those and it’s not the best way to ensure their and others’ wellbeing imo. I’m just saying – not all people will be like that. That’s what I want to believe. So hopefully let’s not put everyone in the same bag, keep supporting each other, WHILE allowing each other to advocate for our own visibility, without having to self-erase or self-censor to accomodate to what haters might say.

It’ll be tougher this way, maybe, because humans seem to like to draw extreme conclusions very quick, but I don’t believe there’s any better way for us all to be alright and stay alright on the long run.

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Being a sex-positive personally-sex-repulsed ace is weird cuz like reading about sex? Awesome. Writing about sex? Not much more intolerable than writing about anything else. Sex is good. Sex is normal. Sex is only as important as you let/want it to be. Kinks are natural expressions of sexuality. Sexual purity is a scam. Bodies are nothing to be ashamed of. Sex work is no more exploitative than any other kind of labor. If you touch me I will throw up on you.

44K notes

·

View notes