Side blog. Vote-shamer <3 Aggressively pragmatic. Got called out because I bravely said people should wash their butts every day. (No TERFs)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Men: screaming and crying and throwing up WHY WON’T WOMEN DATE ME???!?!

Also men:

They really think emotional abuse is soooo funnee, a le epic meme joak. But how dare women stop dating men uwu

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

This old sack of mothballs who's never accomplished anything in the Senate and who LOST by millions of votes both times he left his weird ass bubble of Vermont will never stop jerking off to his own massive ego to consider that maybe, just maybe, he doesn't actually know how to win a presidential election. It's so fucking ridiculous to compare a Democratic primary in one of the bluest cities in the country to a presidential campaign, and what did Mr. 2x Primary Loser specifically have to say?

Go fuck yourself, you ratfucking loser. Like, are you kidding me? Harris shouldn't have paid for ads on TV? There's no presidential campaign that doesn't have ads, and she needed to introduce herself to as many people across the country as possible within 100 days, so TV ads were a way to do that, and by the way, I remember seeing Bernie run ads on TV back when he ran for president!

And what a fucking insult to the huge grassroots campaign Harris did have. Harris supporters across the country were knocking on doors for her! People knocked on my door for her! But oops oops OOPS that doesn't matter to the 2nd sorest loser in the world behind Donald Trump.

And again with the same fucking spiel he always gives about "taking money from billionaires", as if Harris hadn't instantly raised a shit ton of money from individual small donors across the country when her candidacy was announced! God, it's just 30 years of screaming about billionaires with this guy. Get new material, crusty ass!

I'm tired of waiting for this man to croak. We need to start encouraging him to kill himself.

#I hate him so much#we'd be so much better off if his mother had aborted him#I'm so serious about that

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it’s quite interesting that my posts expressing that a) immigrants subject to deportation literally could not vote in 2024 and aren’t responsible for Trump b) many natural born citizens of all backgrounds hold some kind of xenophobia against immigrants and should reflect on their biases c) my career of working with immigrants every day informs my views on this matter, have ruffled some feathers to the point of getting blocked—even by users who aren’t even American. Sorry this isn’t just abstract internet discourse for me and I don’t think it’s cool to throw immigrants under the bus, I guess? 🤷♀️ Also, the idea of getting mad at someone for sticking up for immigrants in a country you don’t even live in……….log off.

#out of ALL posts I’ve made too#I feel like I’ve tried to be measured with this#and these are far from my angriest posts#but. I don’t think there’s a progressive way to smugly shrug at deportations. so that warrants a block lmao

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do realize that this is a small thing compared to the loss of human life but it horrifies me and upsets me that that fucker also murdered Melissa Hortman’s golden retriever

#:(#totally legitimate to be upset about the dog too#a Republican extremist killed innocent beings#human and canine#it’s not surprising at all that someone so cold and cruel would kill an animal like that too#animal death tw

401 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can’t find a previous post I made like this but one of the many bleak things about the past decade is that Trump showcased just how important civic engagement is, and how everyone should be informed citizens and vote because the GOP is insanely evil and elections can have dire consequences, and people’s response was to scream and rage at the expectation to give a shit about any of that. To the lazy and selfish, there’s nothing more offensive than asking them to pay attention and give a shit about anything but themselves. They’d rather let everything go to hell in a hand basket than read the news and fill out a ballot

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are you using chatgpt to get through college. Why are you spending so much time and money on something just to be functionally illiterate and have zero new skills at the end of it all. Literally shooting yourself in the foot. If you want to waste thirty grand you can always just buy a sportscar.

#I love how every AI stan just winds up telling us how stupid they are in their pathetic defense of it#truly like they^^ said AI stans cannot imagine that people have like. real fucking jobs lmao#real jobs that require real knowledge and expertise#ALSO 'lulz AI frees up time-' TIME FOR WHAT#WHAT ARE YOU DOING THAT'S SO IMPORTANT#AND NO 'SCROLLING THROUGH TIKTOK' IS NOT AN ACCEPTABLE ANSWER#anti ai#queued

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

We must point at the blood on the hands of every person who didn't vote for Kamala Harris for the rest of their worthless lives. It doesn't matter how many vulnerable people suffer; obnoxious edgelords posting from their comfy bedrooms in the West don't care

(Link to thread)

Remember: the ends of the horseshoe meet with MAGA and tankies thinking "it's fine for countless people to die for the sake of my ideology."

Bonus:

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

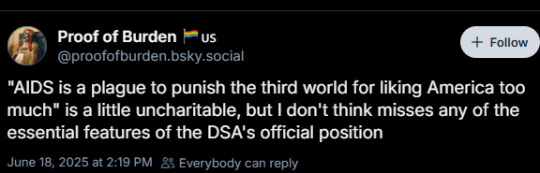

Sometimes I think about how a significant chunk of American political discourse and online political discourse in general over the past 10 years has been dedicated to pretending this tweet was not true or was never actually posted

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

It guts me how there were ads showing stories of women affected by Republican abortion bans that outright put "Trump did this" up on the screen at the end, and even the Lincoln Project had an ad targeting men whose daughters could die of a abortion bans, and yet the "Dobbs effect" was gone by Election Day.

Why is this? Two main reasons. First of all, men do not care about women** dying of abortion bans. Let's just be real here. The worst of them actively think any woman who gets an abortion for any reason did something wrong and deserves to suffer, but a lot of them are simply apathetic to women's healthcare and lives. They do not care. Women's issues don't exist to them, it's not a cause worth fighting for. They see no reason to care; they can't imagine even thinking enough about women's rights to actually vote in favor of them. If men vote on women's rights, they vote for a serial rapist to further rip them away, evidently. That's it.

The second reason is that too many women have bought the patriarchy's bullshit, not simply about the women who get abortions being evil, but being told that their rights are ~frivolous~ girlboss bullshit and they're not actually oppressed for being women--don't be hysterical--and they're actually a super selfish bitch for voting to preserve their rights instead of [insert any other cause that's deemed more important than women's rights here].

Reason #1 should wake people up to how little men care about women, and reason #2 should wake people up to how many women have been taught to devalue themselves and their rights.

(**Yes, people who aren't women need abortions, too, but anti-abortion laws are primarily driven by misogyny and meant to target cis women most of all.)

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been 3 years since Dobbs and I have not forgiven the deliberate, coordinated lying about what led to the death of Roe all to maintain the only constant, real principle the Online left has anymore of "we must not vote or support Democrats no matter the human cost."

I made a post recently about why the Dobbs effect was gone by the 2024 election, but I didn’t mention this:

Dobbs is one of the clearest consequences of Republican power in modern history. They spent decades campaigning on killing Roe, and loyally lining up to vote red to give Republicans enough power to stack the courts. They also spent decades chipping away at abortion rights in states they controlled.

In the face of Republicans, and Republicans alone, ripping away women’s rights like they said they would, the left immediately attacked Democrats. It was literally the day of the ruling, and in between posts from distressed women, you saw leftists screaming at Democrats. They spread disinformation about how this was all secretly Dems’ fault for not stopping Republicans (who apparently have no agency) by using votes they NEVER had to pass federal abortion legislation, and they screamed at anyone who mentioned how every liberal in 2016 told them Roe and SCOTUS were on the ballot in 2016. It didn’t matter how many times people fact-checked them, their mission was clear: ratfuck Democrats and spread the lie that Dobbs was their fault as much as possible.

I do think you’re genuinely stupid if you fell for that bullshit, but who knows if the constant, dedicated message that the erosion of women’s rights was akshewally Dems’ fault and you shouldn’t vote blue did kill the post-Dobbs momentum Democrats had in 2022.

I remember crying on the day Dobbs happened and my friend who was in the process of becoming a tankie was like “that’s really sad but I blame Democrats.” Her ass was sitting in Europe and her response to an American woman crying over the loss of American women’s bodily autonomy was to blame Dems. That’s how thoroughly the “everything is Democrats’ faults and Republicans are mere forces of nature” ratfucking had infiltrated online leftist spaces by then.

#I'd take 2022 back over 2025 don't get me wrong#but my god can we talk about how traumatizing June 2022 was?#Amber Heard was tormented on the world stage and Roe was killed in the same MONTH#and no those two things aren't unrelated!

375 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huh, it’s almost like the president of the United States can’t unilaterally force two autonomous, independent parties to agree to a ceasefire. But I was assured otherwise for a solid year and a half by everyone online who screamed "ceasefire now!" and ignored when a certain group repeatedly rejected those ceasefire offers. Hm! It's almost like I made a post way back in November 2023 saying that the people acting like the president could just end a war in the Middle East with a phone call were no different from MAGA believing Trump could waltz into a room and get world leaders to listen to him by acting like a big, tough guy. Hm, hm, hm,

#and to be clear wanting a ceasefire wasn't wrong#it was the childishly simplistic view on foreign policy that was wrong

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is really good in both acknowledging that humans have wanted to look at erotica since forever, and the god damn misogyny of modern pornography. These parts stood out to me, and it gets to the point that so many people on this anti-feminism website miss:

As the decade progressed, photographers lay on sidewalks trying to get up-skirt, genital-exposing pictures of actresses who’d only just turned 18, and female celebrities psychologically disintegrated in full view of the cameras; what remained consistent was how people kept on watching. We had been conditioned to see people on our computer screens not as human beings but as characters in an ongoing, multiplatform story, whose degradation was all part of the grand spectacle. Male aggression and female submission had been coded into the ways women in public were treated. The photographers who haunted Princess Diana until her death, in 1997, had supposedly used violent language to describe their methods: They “blitzed her” as a group, “whacked her,” “hose[d] her down.” The overwhelmed princess once reportedly shouted at them to go “rape someone else.” In her 2023 memoir, The Woman in Me, Britney Spears describes how she flipped out after a photographer repeatedly harassed her during a moment of crisis, attacking him with an umbrella. “Later, that paparazzo would say in an interview for a documentary about me, ‘That was not a good night for her … But it was a good night for us—’cause we got the money shot.’ ”

The vivisection of women peaked in 2007, when, within the space of a few months, Spears shaved her head, Anna Nicole Smith fatally overdosed on combined prescription drugs, a sobbing Paris Hilton went to jail, and a pantsuit-clad Hillary Clinton announced that she was running for president. All of this was documented in what felt like real time, in a rolling barrage of blog posts, paparazzi photos, and cable-news clips. The cruelty and disdain expressed toward women during the aughts were, I’d argue, more significant and enduring than they’ve been given credit for. We were being asked to see a woman as capable of occupying the most powerful position in the world, in a media landscape conditioned to view us as high-definition train wrecks...

The specter of a Hillary Clinton presidency was immediately presented by some pundits in objectified terms. How else were women in this era to be understood? “Will this country want to actually watch a woman get older before their eyes on a daily basis?” Rush Limbaugh asked on his radio show in 2007. It’s no longer at all surprising to me that a capable and experienced woman lost to a reality‐TV character and virulent misogynist in 2016 (to say nothing of 2024). The overwhelming cultural message that Americans had absorbed during the decades leading up to Clinton’s first presidential campaign enshrined the idea that women fundamentally lacked the qualities required to gain and exercise authority: intelligence, morality, dignity. Clinton tends to loom large in any discussion of female political ambition in this century, but there’s another woman whose rapid, turbulent ascent fittingly illustrates the cultural trends of this era. In August 2008, when Senator John McCain announced Sarah Palin as his presidential running mate, the 44‐year‐old Alaska governor was virtually unheard-of outside her state...

What did it mean, that American culture’s immediate response to a woman’s political ascent was to put her on her back? Who’s Nailin’ Paylin? was absurd, but it made undeniable all the ways in which porn had reset ideas about women. “Porn does not inform, or persuade, or debate,” Amia Srinivasan wrote in her 2021 book, The Right to Sex. “Porn trains.” For the past few decades, it has trained men to see women as objects—as things to silence, restrain, fetishize, or brutalize. But it has trained women, too. In 2013, the social psychologist Rachel M. Calogero found that the more women were prone to self‐objectification—the defining message of porn and aughts mass media—the less inclined they were toward gender-based activism and the pursuit of social justice. This, to me, goes a long way toward explaining what happened to women and power in the early 21st century. For decades, male supremacy was being coded into our culture, in ways that were both outlandish and so subtle, they were hard to question. Given what Millennials had grown up with, it wasn’t surprising when they started examining their own conditioning through storytelling, taking stock of what the first decade of the new century had wrought. One of the most prominent was Lena Dunham, whose HBO series, Girls, debuted in 2012. The show reckoned with, among other subjects, the indignities of sleeping with 20-something men whose sexual scripts and practices now tended to be ripped right out of porn. (In the second episode, while Dunham’s Hannah is having sex with Adam Driver’s Adam, he calls her a “dirty little whore” and puts his hand around her neck before he ejaculates. “That was so good—I almost came,” she says meekly in response.) By the time Sam Levinson’s Euphoria debuted in 2019, explicit sexual imagery was omnipresent among teenagers, something Zendaya’s protagonist, Rue, notes in a voice-over: “I’m sorry. I know your generation relied on flowers and fathers’ permission, but it’s 2019, and unless you’re Amish, nudes are the currency of love, so stop shaming us. Shame the assholes who create password-protected online directories of naked, underage girls.”

Euphoria was provocative to a fault...Levinson has insisted that his show was simply trying to convey how rapidly the experience of adolescence was changing. By the time Euphoria debuted, porn’s practices and mores had thoroughly defined not just culture but sex itself. That year, a survey found that 38 percent of British women younger than 40 had experienced unwanted violent behavior—including slapping, gagging, spitting, or choking—during consensual sex. A culture of unfettered male dominance had simultaneously sprawled across the rest of the web, as misogynistic abuse and harassment manifested in different communities and targeted campaigns, and even culminated in episodes of real violence. “Incels,” as certain disaffected young men began calling themselves, hate women for not being more sexually agreeable, as though sex is a commodity that should be redistributed to the needy rather than a matter of personal desire. That particular term was relatively new, but the rest of their verbiage was familiar: One 2021 study conducted by researchers in Britain found that much of the language used in incel forums is identical to the language used in mainstream pornography, routinely employed to dehumanize and sexually humiliate women. The impulse to subject women to sexual violence obviously predates porn. And not all porn is degrading or hateful toward women, even if much of it is. But, looking back across the past few decades, it’s hard not to see that the explosion of pornography as a cultural product during the 1990s and 2000s changed the terms of how women were to be viewed and understood. The ramifications have rippled throughout our on- and offline lives. In 2014, two years before Trump’s first presidential victory, approximately 70 percent of American men ages 18 to 39 reported using pornography within the past year. Trump’s election confirmed how widespread and even tacitly accepted the degradation of women had become: Here was a winning candidate who’d been accused of sexual misconduct by dozens of women (which he has denied); the first “porn president,” as my colleague Caitlin Flanagan wrote, for whom the reduction of women to sexual objects was as natural as breathing.

By 2024, the debasement of women in public life had become so instinctive that Kamala Harris was subjected to sexual slurs in the lead-up to her presidential campaign—even before she was officially a candidate. On Fox Business, a guest labeled Harris “the original Hawk Tuah girl,” a reference to a viral video about blow jobs; Trump himself reposted memes inferring that Harris had used sex to further her career. In October, a week and a half before the election, a billboard appeared in Ohio that depicted Harris on her hands and knees, mouth agape, about to engage in oral sex with a frenzied look on her face...

Porn’s logic of male supremacy has successfully saturated politics. The new administration is in thrall to the manosphere, and unabashed about its project of white masculine domination; in 2025, just 15 percent of Republican members of Congress are women. Young men and boys are growing up with misogynist influencers who assert that women are something less than fully human. “One must believe in the existence of the person in order to recognize the authenticity of her suffering,” Andrea Dworkin wrote in her 1983 book, Right-Wing Women, during another period of anti-feminist backlash. “Neither men nor women believe in the existence of women as significant beings.”

In 1999, the year I turned 16, there were three cultural events that seemed to define what it meant to be a young woman—a girl—facing down the new millennium. In April, Britney Spears appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone lying on a pink bed wearing polka-dot panties and a black push‐up bra, clutching a Teletubby doll with one hand and a phone with the other. In September, DreamWorks released American Beauty, a movie in which a middle‐aged man has florid sexual fantasies about his teenage daughter’s best friend; the film later won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture. In November, the teen-clothing brand Abercrombie & Fitch released its holiday catalog, titled “Naughty or Nice,” which featured nude photo spreads, sly references to oral sex and threesomes, and an interview with the porn actor Jenna Jameson, in which she was repeatedly harangued by the interviewer to let him touch her breasts.

The tail end of the ’90s was the era of Clinton sex scandals and Jerry Springer and the launch of a neat new drug called Viagra, a period when sex saturated mainstream culture. In the Spears profile, the interviewer, Steven Daly, alternates between lust—the logo on her Baby Phat T‐shirt, he notes, is “distended by her ample chest”—and detached observation that the sexuality of teen idols is just a “carefully baited” trap to sell records to suckers. Being a teen myself, I found it hard to discern the irony. What was obvious to my friends and to me was that power, for women, was sexual in nature. There was no other kind, or none worth having. I attended an all-girls school run by stern second-wave feminists, who told us that we could succeed in any field or industry we chose. But that messaging was obliterated by the entertainment we absorbed all day long, which had been thoroughly shaped by the one defining art form of the late 20th century: porn.

By this point in history, pornography, as Frank Rich argued in a New York Times Magazine story in 2001, was American culture, even if no one wanted to admit it. Porn was a multibillion-dollar industry in the United States—worth more money, Rich suggested, than consumers in the U.S. spent on movie tickets in a year, and purportedly “a bigger business than professional football, basketball and baseball put together.” It was a cultural product few people bragged about consuming, but it was infiltrating our collective imagination nevertheless, in ways no one could fully assess at the time. And things were just getting started. Porn helped define the structure and mores of the internet. It dominated popular music, as the biggest hip-hop stars of the era released hard-core films and the teenage stars of my generation redefined themselves for adulthood with fetish-tweaking music videos. In 2003, Snoop Dogg arrived at the MTV Video Music Awards with two women wearing dog collars attached to leashes that he held in each hand, to minimal protest. In 2004, the esteemed fashion photographer Terry Richardson released a coffee-table book that predominantly featured pictures of his own erect penis, and the models he’d cajoled into posing with it.

This period of porno chic arrived with an asterisk that insisted it was all a game, a postmodern, sex-positive appropriation of porn’s tropes and aesthetics. But for women, particularly those of us just entering adulthood, the rules of that game were clear: We were the ultimate Millennial commodity, our bodies cheerfully co-opted and replicated as media content within the public domain. If we complained, we were vilified as prudes or scolds. This kind of sexualization was “empowering,” everyone kept insisting. But the form of power we were being allotted wasn’t the sort you accrue over a lifetime, in the manner of education or money or professional experience. It was all about youth, attention, and a willingness to be in on the joke, even when we were the punch line.

What did growing up against this particular cultural backdrop do to me? What did it do to all of us? I didn’t start trying to process this particular initiation into adulthood until two decades later. A few months into the coronavirus pandemic, I gave birth to twins, and becoming a parent in almost complete isolation triggered a kind of identity crisis. I was too exhausted to read; I could no more sit through an entire movie than I could sprout wings and fly. When I went back to work, the #MeToo movement had many women parsing their own historical experiences of assault and abuse. All of the subjects I wrote about seemed to be circling the same theme: an environment that had been set up against women from the beginning.

In 2022, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, progress no longer seemed inevitable. The recreational misogyny of the aughts was back, this time with new technology and a cult figurehead, Andrew Tate, who’d briefly appeared on the reality series Big Brother while under investigation for rape. (In the years since, Tate has been accused by multiple other women of sexual misconduct and is now under investigation for human trafficking. He has denied all allegations against him.) On TikTok, doll‐like women murmured in affectless monologues about living the financially dependent dream of a “soft, feminine life.” In 2024, when Kamala Harris ran for president, she was subjected to a targeted campaign of sexualized slander, some of it broadcast personally by Donald Trump. And when Trump became president for the second time, his victory was jubilantly claimed by misogynists, who taunted women with a new catchphrase: “Your body, my choice.”

So much of this seemed familiar. It was all too reminiscent of the beginning of the 21st century, when feminism felt similarly nebulous and inert, squashed by a cultural explosion of jokey extremity and Technicolor objectification. This was the environment that Millennial women had been raised in. It informed how we felt about ourselves, how we saw one another, and what we understood women to be capable of. It colored our ambitions, our sense of self, our relationships, our bodies, our work, and our art. I came to believe that we couldn’t move forward without fully reckoning with how the culture of the aughts had defined us.

But as I revisited the entertainment of the ’90s and 2000s, what surprised me the most was how much the murk of the era came right from porn. It’s a more influential cultural genre than any other, and yet its impact outside of people’s homes and hotel rooms has hardly been analyzed. I should say here that I’m not opposed to porn on principle. Some of it is liberating; some of it is ethical; a tiny amount of it is even devoted to understanding female desire in a universe built on the male gaze and money shots. Still, in studying porn’s long cultural shadow, I’ve come to agree with the radical feminist Andrea Dworkin, who wrote in 1981 that “pornography incarnates male supremacy. It is the DNA of male dominance.” Porn has undeniably changed how people have sex, as researchers and anyone who has even fleeting experience with dating apps can attest. But it has also changed our culture and, in doing so, has filtered into our subconscious minds, beyond the reach of rationality and reason. We are all living in the world porn made.

Pornography has tended to be at the forefront of emerging technologies, for the simple reason that titillation mixed with novelty is a powerful draw. The porn industry adopted VHS before many Americans had even heard of it. In 1977, when videocassette players first went on the market, up to 75 percent of the tapes being sold were pornographic. Over the course of the 1980s, as AIDS became an unprecedented public-health crisis, both VHS adoption and porn consumption surged, fueled by convenience (movies you could watch alone, at home) and fear (casual sex was much safer as a solitary endeavor). Independent video stores, which pragmatically stocked the explicit tapes that chains such as Blockbuster refused to carry, also realized that porn could shore up their bottom line—in 1985, Americans rented 75 million adult videos. A decade later, that number had increased almost tenfold, according to the trade magazine Adult Video News.

America’s adoption of hard-core porn as a leisure pursuit happened so quickly that its effect on popular culture was hard to measure in the moment. But, as David Friend writes in his book The Naughty Nineties, the final decade of the 20th century was consumed with sex, a subject that dominated politics and art, but also public health. By the end of 1990, AIDS had claimed more than 120,000 lives in the United States; one‐fifth of the victims had lived in New York City, the epicenter of fashion, art, music, media, and advertising. The idea that sex could kill you had led to two wildly divergent schools of thought in American culture. One, nicknamed the New Traditionalism after a nostalgic Good Housekeeping ad campaign, called for a revival of old‐fashioned family values, suggesting that women go home and stay there. (The 1987 movie Fatal Attraction made this fear of a corrupted American culture literal, in the form of Glenn Close’s sexually adventurous, bunny‐boiling career woman, the fling who won’t be flung.) The other, the New Voyeurism, embraced sex—as a spectator sport. “At a time when doing it has become excessively dangerous, looking at it, reading about it, thinking about it have become a necessity,” a Newsweek feature on Madonna declared in 1992. “AIDS has pushed voyeurism from the sexual second tier into the front row.”

Already, the ’90s were a decade of unprecedented sexual openness. Explicit representations of sex were no longer taboo; they were, in fact, now considered vital for public education. This shift meant that artists could experiment with pornographic tropes in plain sight. Near the end of 1990, Madonna released a video to accompany her new single, “Justify My Love,” that set the tone for the coming years: audacious, fiercely sexual, a bit trollish. Madonna, shot in black and white, is seen walking down a hotel hallway toward an assignation, limping slightly in heels and a black raincoat, clutching her head as if in pain. As she passes different doorways, we see fleeting glimpses of the rooms’ occupants, watching us watch them. After she enters a room, orgiastic flashes of different scenes appear: Madonna with her lover (played by her real‐life boyfriend at the time, the amiable lunk Tony Ward); a man lacing a woman into a rubber corset; a dancer in a unitard contorting into shifting positions; Ward watching Madonna with another partner, then getting trussed up in a fetish harness. Finally, Madonna puts on her coat and leaves, laughing, renewed and jubilant, no longer tired.

The brazen sexuality of the video was the whole point. Madonna had lost many friends to AIDS, the artist Keith Haring among them. But she was adamant that sexual freedom, fantasy, and pleasure not be sacrificed amid the devastation. What some people call “sex positivity” today was, in the ’90s, understood by those promoting it as an expression of defiance and celebration. In 1990, HBO debuted Real Sex, an unfiltered peek into the lives of strippers, phone‐sex operators, porn directors, and exhibitionist couples looking for an audience. The show, according to HBO’s then–head of documentary programming, Sheila Nevins, was a direct response to fears about sexuality that had been stoked by the AIDS crisis. Depicting sex, she said, had become “much more important because of all the terror that surrounds it.” Four years later, Janet Jackson released a video for “Any Time, Any Place” that teased the same voyeuristic impulses at play in “Justify My Love”: An elderly neighbor looks on, disapprovingly, as Jackson pushes her lover’s head down while he’s on top of her—a then-radical assertion of sexual power and equality.

It was around this same time that then–presidential candidate Bill Clinton admitted on 60 Minutes, with his wife at his side, to “causing pain” in his marriage, referencing an affair with the TV reporter Gennifer Flowers. “I have said things to you tonight,” he acknowledged, “and to the American people from the beginning, that no American politician ever has.” Clinton’s public acknowledgment of scandal, nonspecific though it might have been, was unprecedented, and it helped underscore how much his era would embrace confession and self-exposure. The Jerry Springer Show had debuted in 1991, offering Americans a space to air their wildest secrets to a nation of rubberneckers. By the end of the decade, we had been obliged to consider what stains on a blue dress signified; what, exactly, Hugh Grant was arrested for on Sunset Boulevard; whether John Wayne Bobbitt got what he deserved; and whether a person might sell themselves for $1 million, as Demi Moore’s financially struggling Diana did in Indecent Proposal.

In the mid‐’90s, DJ Yella, of the hip-hop group N.W.A, started directing adult movies, kicking off a collaborative relationship between hip-hop and porn. In 1996, Lil’ Kim’s debut album, Hard Core, opened with what sounded like a recording of a man going to an adult theater, purchasing a ticket to a porn movie, unzipping his pants, and audibly masturbating when Kim appeared as its star. In 1998, the tired porn trope of the sexy schoolgirl was defibrillated by the video for “Baby One More Time,” in which the 16‐year‐old Britney Spears thrust her hips with an intensity that, now, I find more unsettling than her much-discussed exposed midsection. The video works because Spears seems so earnest, so unaware of how people might be reading her. She looks so young. This is teen sexuality as postmodern spectacle: a mishmash of transgressive allusions transmuted into a product that can’t possibly be interpreted as serious.

In 2001, Snoop Dogg starred in the top‐selling hard-core pornographic video in America, “Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle.” (Snoop didn’t perform explicit acts on camera, but rather acted as a hype man and an emcee, introducing performers and providing the soundtrack.) For fans, this was less a shift toward transgression than a cultural crossover event. “We’ve been using sex to sell music for years,” Camille Evans, a magazine publisher, told The New York Times. “Now we’re just flipping it to have music sell sex.” At the beginning of the decade, the provocative, expressive experimentation of artists like Madonna and Jackson had foregrounded women’s desires. By the end, the cultural dominance of porn was pushing a much more regressive set of sexual standards. And the technological mechanisms that helped bolster this dominance would come to underscore—and exacerbate—a potent idea: that women existed only for men’s pleasure.

The impulse to look at eroticized pictures of other people, of course, is as old as art itself. What changed toward the end of the 20th century was the ease with which pornographic images and videos could be made, disseminated, and turned into profit. If you investigate the origins of today’s most prominent online platforms, a surprising number stem from the equivalent impulse of an eighth grader typing boobies into a search bar. Google Images was created after Jennifer Lopez wore a vivid‐green jungle‐print Versace dress to the 2000 Grammy Awards, cut so spectacularly low that it became the most popular search query Google had seen to date. Facebook was born in 2004, after Mark Zuckerberg first experimented with making a website dedicated to assessing the relative hotness of Harvard undergraduates. And when Jawed Karim, Chad Hurley, and Steve Chen founded YouTube in 2005, it was partly because Karim had been searching for videos of Janet Jackson’s “wardrobe malfunction” at the Super Bowl and couldn’t easily find one. “Sex is the one drive that can shape immediate consumer response,” Gerard Van der Leun wrote in January 1993, in the first-ever issue of Wired, considering the extent to which the early internet was already being informed by sexual content.

In the mid-’90s, with porn now firmly propping up the rest of the web, and with shows such as Real Sex typifying the kinds of footage Americans wanted to watch, two women found themselves traversing fresh technological terrain. Both would end up determining the future of the internet. One was Pamela Anderson, who in 1997 became the first celebrity to have sexually explicit footage of herself disseminated on the internet without her consent. Despite the fact that the video in question was extremely private—made by herself and her husband, Tommy Lee, on their honeymoon, and stolen from a safe in their Malibu home—millions of people delighted at the opportunity to see something wholly new: a celebrity, an American icon, as exposed as anyone could possibly be.

When Anderson sued Penthouse, which was trying to profit from her tape, the company’s lawyer told her that because she’d previously posed nude for Playboy, she could not legitimately claim that she was being victimized and had “forfeited” her right to privacy. The following year, exhausted and seven months pregnant, Anderson agreed to let a distributor broadcast the tape online if he stopped selling physical copies on VHS, not understanding that the internet was already a thriving marketplace for porn. The footage became the quintessential cultural product of the ’90s: One of the most famous women in the world lost the right to a private sex life, and countless more people learned how to get online, enticed by a novel form of public spectacle. That very same year, Girls Gone Wild made its infomercial debut, selling videos in which college girls (and, often, high schoolers) revealed their breasts, made out with one another, and performed stripteases on camera, all for the low, low compensation of branded trucker caps and dubious street cred.

Just as Anderson was making futile attempts to protect her own image, an unknown college student was becoming the first woman to allow the internet unfiltered, unmediated access to her life. In 1996, a 19‐year‐old student at Dickinson College named Jennifer Ringley bought a webcam that she connected to a computer in her dorm room. Ringley was, in her words, a “computer nerd,” and she wanted to see if she could write a programming script that would take pictures in real time and upload them to her website. The script worked, and Ringley began to post: regular, unposed, black‐and‐white images that published first every 15 minutes, and then every three. The banality of the pictures seemed to be, for her, the draw of the project: She sat at her computer, she ate, she talked on the phone, she slept. “I think the camera would be a lot less interesting if I paid that much attention to it,” Ringley told Ira Glass on a 1997 episode of This American Life, by which time her “JenniCam” was getting upwards of half a million hits a day. “It would be more of a staged show. And you can go see a staged show anywhere.”

There was nothing particularly erotic about these photos, but the majority of visitors to her site, she said, were men. Many people seemed interested in JenniCam less for its humdrum snapshots of everyday life and more for the long‐odds hope that Ringley would do something salacious while they watched her. The first time she invited a date over who didn’t flee as soon as he saw the camera, so many viewers flocked to her site that they crashed the server and ended up seeing nothing. Ringley’s intentions weren’t to actively court what the film theorist Laura Mulvey termed “the male gaze,” and the camera didn’t deter her from doing anything that she felt like doing. She was opening up her life online to try something different, brokering a parasocial intimacy with the people watching her. But what most of them wanted to see—and what even well‐meaning interpreters such as Glass and David Letterman wanted to talk about—was nudity and sex, the most fascinating contours of private life turned into public exhibition.

The internet, at this point, still felt redolent with possibility. Going online was an opportunity to experiment with identity, self-presentation, communication. For women, though, what was becoming clear was how much we were already the primary objects of the online age. As the ’90s went by, third-wave feminism was edged out by postfeminism, a cheerful, consumerist movement arguing that feminism had achieved what it needed to and now women were largely free to behave just like men, sexually liberated and socially empowered. The catch was that we were also subtly being conditioned to perform.

I’m fascinated by Ringley because in her effort to find a new way to connect online, she set a template for how women would learn to act. Her experiments with radical honesty influenced the confessorial online writing of the 2000s. And her willingness to become a living, breathing character on people’s computer screens, coupled with the expectations that porn had already set, shaped the future of both celebrity and sex work. Before Instagram and TikTok and OnlyFans, even before blogs and MySpace and reality television, the internet had reaffirmed that women were to be what Mulvey defined as “erotic objects” whose bodies were very much in the public domain. With no other direction to go in, 21st-century porn would exploit this idea to new extremes.

By the time I was in college, porn was everywhere in popular culture, providing a recognizable aesthetic that filtered through fashion magazines, advertising, independent film, and online media. In 2004, the Deitch Projects gallery, in New York City, debuted a splashy exhibition of new work by Terry Richardson, accompanied by the publication of his coffee-table book, both titled Terryworld. Richardson, by that point, was the torchbearer for a visual mode that was irresistible at the beginning of the 21st century: a tacky, sweaty genre of portraiture that gave Hollywood stars and random passersby the same high‐flash, semisurprised, not‐quite‐human aura. Richardson’s book included images of Dennis Hopper, Kate Moss, and Pharrell Williams, as well as the photographer’s erect penis, which he captured in different settings: resting on a brown teddy bear, pointing down at the head of a seemingly passed‐out model whom Richardson holds by the hair; choking another model whose eyes display what appears to be discomfort. (In 2017, Condé Nast finally ended its working relationship with Richardson after years of well-publicized allegations by models that Richardson relentlessly harassed, manipulated, and coerced them into sexual activity during shoots; Richardson has always denied the allegations.)

The tone of Richardson’s work—the way it flattens its subjects into two‐dimensional beings seen through the photographer’s leering, cynical lens—might feel discomfiting now, but the substance of it, in that moment, wasn’t unusual. In the early 2000s, popular culture was doing everything it could to emulate hard-core pornography, playing with its tropes and lack of boundaries. In 2003, the British photographers Rankin and David Bailey (both of whom had previously shot Queen Elizabeth II) collaborated on a series devoted to explicit images of female genitalia that was known officially as “Rankin + Bailey: Down Under” and unofficially as “the pussy show.” At the Cannes Film Festival, the British filmmaker Michael Winterbottom—who’d previously directed a Thomas Hardy adaptation starring Kate Winslet—debuted his movie 9 Songs, the story of a young couple’s relationship that contained multiple scenes of unsimulated sex. In the summer of 2004, Jenna Jameson’s memoir, How to Make Love Like a Porn Star, spent six weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. In October, stars including Ben Stiller and Rachel Weisz attended the opening of Timothy Greenfield‐Sanders’s XXX, a photographic series featuring porn actors that was accompanied by an HBO documentary—a project that captured the porno-chic style of the moment. “Fashion has tremendous influence on how the culture changes,” Greenfield‐Sanders told a Times reporter. “And porn has had a tremendous influence on fashion.”

At the same time, porn was adapting to a world in which it was no longer on the margins. The more mainstream culture ripped off its imagery and its sexual excess, the more pornographers had to find new ways to stand out. The techno-optimistic vision of porn saw the medium as a sexually liberating force for everyone. But as the industry adapted to the jaded palate of the contemporary porn consumer, it pushed boundaries further. “The new element,” Martin Amis wrote in 2001, reporting for The Guardian on the business of porn, “is violence.” And it was overwhelmingly being inflicted on women, in content so degrading, it sometimes made even Larry Flynt, the Hustler publisher, uncomfortable.

Porn was getting crueler, and so was popular culture, as both met a growing taste for extremity. In 1999, a documentary was released about the porn actor Annabel Chong, who’d had sex 251 times in a single 10‐hour period and then went on The Jerry Springer Show to discuss her experience, while audience members gasped and cringed at the spectacle. Chong’s feat of endurance and the 2002 Gaspar Noé film Irréversible—which included a nine‐minute anal-rape scene featuring the actor Monica Bellucci—were arguably extensions of the same idea: testing the limits of what men could do to women for entertainment while the cameras rolled.

As the decade progressed, photographers lay on sidewalks trying to get up-skirt, genital-exposing pictures of actresses who’d only just turned 18, and female celebrities psychologically disintegrated in full view of the cameras; what remained consistent was how people kept on watching. We had been conditioned to see people on our computer screens not as human beings but as characters in an ongoing, multiplatform story, whose degradation was all part of the grand spectacle. Male aggression and female submission had been coded into the ways women in public were treated. The photographers who haunted Princess Diana until her death, in 1997, had supposedly used violent language to describe their methods: They “blitzed her” as a group, “whacked her,” “hose[d] her down.” The overwhelmed princess once reportedly shouted at them to go “rape someone else.” In her 2023 memoir, The Woman in Me, Britney Spears describes how she flipped out after a photographer repeatedly harassed her during a moment of crisis, attacking him with an umbrella. “Later, that paparazzo would say in an interview for a documentary about me, ‘That was not a good night for her … But it was a good night for us—’cause we got the money shot.’ ”

The vivisection of women peaked in 2007, when, within the space of a few months, Spears shaved her head, Anna Nicole Smith fatally overdosed on combined prescription drugs, a sobbing Paris Hilton went to jail, and a pantsuit-clad Hillary Clinton announced that she was running for president. All of this was documented in what felt like real time, in a rolling barrage of blog posts, paparazzi photos, and cable-news clips. The cruelty and disdain expressed toward women during the aughts were, I’d argue, more significant and enduring than they’ve been given credit for. We were being asked to see a woman as capable of occupying the most powerful position in the world, in a media landscape conditioned to view us as high-definition train wrecks. Early in 2008, when Clinton briefly welled up in a coffee shop after a bruising loss in the Iowa caucus, the moment was interpreted as being a melodramatic scandal fit for TMZ and a cynical ploy for attention that eventually won her New Hampshire.

The specter of a Hillary Clinton presidency was immediately presented by some pundits in objectified terms. How else were women in this era to be understood? “Will this country want to actually watch a woman get older before their eyes on a daily basis?” Rush Limbaugh asked on his radio show in 2007. It’s no longer at all surprising to me that a capable and experienced woman lost to a reality‐TV character and virulent misogynist in 2016 (to say nothing of 2024). The overwhelming cultural message that Americans had absorbed during the decades leading up to Clinton’s first presidential campaign enshrined the idea that women fundamentally lacked the qualities required to gain and exercise authority: intelligence, morality, dignity.

Clinton tends to loom large in any discussion of female political ambition in this century, but there’s another woman whose rapid, turbulent ascent fittingly illustrates the cultural trends of this era. In August 2008, when Senator John McCain announced Sarah Palin as his presidential running mate, the 44‐year‐old Alaska governor was virtually unheard-of outside her state. She had minimal political experience: two terms as the mayor of Wasilla, a town with fewer than 7,000 residents at the time, and less than two years as governor. But she was a woman—which the McCain campaign hoped would energize voters—a conservative Christian, and a mother. An early profile of Palin in the Times highlighted the latter identity, describing her as someone who had never had political ambitions of her own but rather was drawn to office reluctantly, out of a pragmatic desire to share her skills. Her successor as mayor described her to the newspaper as just “a P.T.A. mom who got involved.”

Palin also fit neatly into the decade’s understanding of what a woman should be. She’d won the title of Miss Wasilla and had placed as a runner-up in the 1984 Miss Alaska pageant. Mere days after she addressed the Republican National Convention as a candidate for vice president—the first woman ever to do so—Larry Flynt’s production company posted an ad on Craigslist requesting a “Sarah Palin look‐alike for an adult film to be shot in the next 10 days.” Flynt had a history of trying to unite porn and politics: In 1975, one year after launching Hustler, he published photographs of former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis sunbathing nude in Greece, and in 1983, he attempted to run for president himself as a Republican. Who’s Nailin’ Paylin?, which filmed over a weekend in October, starred the porn performer Lisa Ann as Serra Paylin, a politician who thinks the Earth is 10,000 years old, struggles to keep from saying “You betcha,” and participates in hard-core group scenes, including one with satirical versions of Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice.

What did it mean, that American culture’s immediate response to a woman’s political ascent was to put her on her back? Who’s Nailin’ Paylin? was absurd, but it made undeniable all the ways in which porn had reset ideas about women. “Porn does not inform, or persuade, or debate,” Amia Srinivasan wrote in her 2021 book, The Right to Sex. “Porn trains.” For the past few decades, it has trained men to see women as objects—as things to silence, restrain, fetishize, or brutalize. But it has trained women, too. In 2013, the social psychologist Rachel M. Calogero found that the more women were prone to self‐objectification—the defining message of porn and aughts mass media—the less inclined they were toward gender-based activism and the pursuit of social justice. This, to me, goes a long way toward explaining what happened to women and power in the early 21st century. For decades, male supremacy was being coded into our culture, in ways that were both outlandish and so subtle, they were hard to question.

Given what Millennials had grown up with, it wasn’t surprising when they started examining their own conditioning through storytelling, taking stock of what the first decade of the new century had wrought. One of the most prominent was Lena Dunham, whose HBO series, Girls, debuted in 2012. The show reckoned with, among other subjects, the indignities of sleeping with 20-something men whose sexual scripts and practices now tended to be ripped right out of porn. (In the second episode, while Dunham’s Hannah is having sex with Adam Driver’s Adam, he calls her a “dirty little whore” and puts his hand around her neck before he ejaculates. “That was so good—I almost came,” she says meekly in response.) By the time Sam Levinson’s Euphoria debuted in 2019, explicit sexual imagery was omnipresent among teenagers, something Zendaya’s protagonist, Rue, notes in a voice-over: “I’m sorry. I know your generation relied on flowers and fathers’ permission, but it’s 2019, and unless you’re Amish, nudes are the currency of love, so stop shaming us. Shame the assholes who create password-protected online directories of naked, underage girls.”

Euphoria was provocative to a fault—one locker-room montage featuring more than a dozen full-frontal penises felt more like a challenge to find premium cable’s limits than a coherent piece of storytelling. But the series was intent, in a bleakly cynical kind of way, on exploring what porn culture had passed down to the next generation. In one scene, Rue, who battles addiction throughout the series, blithely offers a tutorial on the art of dick pics; in another, she tears apart her house looking for pills. Many of the show’s sex scenes were unnerving: Kat (Barbie Ferreira) loses her virginity after being challenged by other high schoolers to prove she’s not a prude, but she’s secretly filmed and the footage is uploaded to PornHub; she panics that she’ll become a social pariah. Jules (Hunter Schafer) meets a man online named “DominantDaddy” who turns out to be the father of one of her classmates, and when he meets her at a motel to have sex, her pain and forced submission are hard to watch.

Levinson has insisted that his show was simply trying to convey how rapidly the experience of adolescence was changing. By the time Euphoria debuted, porn’s practices and mores had thoroughly defined not just culture but sex itself. That year, a survey found that 38 percent of British women younger than 40 had experienced unwanted violent behavior—including slapping, gagging, spitting, or choking—during consensual sex. A culture of unfettered male dominance had simultaneously sprawled across the rest of the web, as misogynistic abuse and harassment manifested in different communities and targeted campaigns, and even culminated in episodes of real violence. “Incels,” as certain disaffected young men began calling themselves, hate women for not being more sexually agreeable, as though sex is a commodity that should be redistributed to the needy rather than a matter of personal desire. That particular term was relatively new, but the rest of their verbiage was familiar: One 2021 study conducted by researchers in Britain found that much of the language used in incel forums is identical to the language used in mainstream pornography, routinely employed to dehumanize and sexually humiliate women.

The impulse to subject women to sexual violence obviously predates porn. And not all porn is degrading or hateful toward women, even if much of it is. But, looking back across the past few decades, it’s hard not to see that the explosion of pornography as a cultural product during the 1990s and 2000s changed the terms of how women were to be viewed and understood. The ramifications have rippled throughout our on- and offline lives. In 2014, two years before Trump’s first presidential victory, approximately 70 percent of American men ages 18 to 39 reported using pornography within the past year. Trump’s election confirmed how widespread and even tacitly accepted the degradation of women had become: Here was a winning candidate who’d been accused of sexual misconduct by dozens of women (which he has denied); the first “porn president,” as my colleague Caitlin Flanagan wrote, for whom the reduction of women to sexual objects was as natural as breathing.

By 2024, the debasement of women in public life had become so instinctive that Kamala Harris was subjected to sexual slurs in the lead-up to her presidential campaign—even before she was officially a candidate. On Fox Business, a guest labeled Harris “the original Hawk Tuah girl,” a reference to a viral video about blow jobs; Trump himself reposted memes inferring that Harris had used sex to further her career. In October, a week and a half before the election, a billboard appeared in Ohio that depicted Harris on her hands and knees, mouth agape, about to engage in oral sex with a frenzied look on her face. I spent much of the year with my head in my hands. For a moment, it seemed possible, again, that Trump’s hateful rhetoric, his nonsensical diatribes, his coalition of creeps and podcast bros and internet-poisoned trolls might be enough to make a capable woman seem favorable by comparison.

But that wasn’t the case. And as he returned to the presidency, I found myself thinking less about men than about women, particularly some of the women in Trump’s orbit—the ones who trade power for visibility, a high-definition, glaringly enhanced veneer of public womanhood that insists being seen is the same thing as being significant. So much of this century’s popular culture has presented women as spectacles: chaotic, melodramatic, hypersexualized recipients of attention.

Porn’s logic of male supremacy has successfully saturated politics. The new administration is in thrall to the manosphere, and unabashed about its project of white masculine domination; in 2025, just 15 percent of Republican members of Congress are women. Young men and boys are growing up with misogynist influencers who assert that women are something less than fully human. “One must believe in the existence of the person in order to recognize the authenticity of her suffering,” Andrea Dworkin wrote in her 1983 book, Right-Wing Women, during another period of anti-feminist backlash. “Neither men nor women believe in the existence of women as significant beings.”

The first part of her argument stands. That the second part is questionable—regarding how women see themselves, at least—is a positive development. And for all the ways in which popular culture helped enshrine porn as the defining form of modern entertainment, culture may be turning into the one place where we no longer want to be reminded of it. I keep coming back to HBO’s 2023 miniseries The Idol, a work to which Sam Levinson brought all of Euphoria’s provocations and none of its emotional intelligence. The show starred Lily-Rose Depp as a disgraced pop star in the Britney tradition and Abel “The Weeknd” Tesfaye as the nightclub owner and cult leader who seduces her with rough sex and BDSM; its intentions seemed to be to marry premium-cable aesthetics with the hollow transgressions of extreme porn. In one scene, Tesfaye’s character suffocates Depp’s Jocelyn with a scarlet silk robe, then uses a knife to slash a hole so she can breathe, reducing the character to a bright-red slash, a pornographic crevice. Jocelyn’s experiences, the show implied, had empowered her, a suggestion so absurd and anachronistic that viewers could only cringe in response. The Idol was a critical failure that hardly anyone even talked about—a possible sign of progress.

For me, the process of adulthood has been less about lessons learned than unlearned—the steady dismantling of ideas I absorbed before I could really think critically about them. But I still believe that by understanding all of the ways in which women have been diminished and broken down in the recent past, we can identify and defuse those same attacks in the present. Our culture isn’t just entertainment—it’s the means by which we understand and relate to ourselves and one another. In moments when I’m galled by how cyclical backlash and progress are, it’s consoling to remember that most women have newfound language and skepticism that I couldn’t have imagined while watching Girls Gone Wild or listening to “P.I.M.P.” Both of those developments feed the kind of unlearning, in other words, after which power is real, change is necessary, and wholly new stories can begin.

#it really drives me nuts that on this website#you can't take a critical look at porn and the misogyny involved within it#without people screaming and acting like you're a nun#like it's playing dumbbbbbb ofc the porn industry is misogynistic and what men see in porn has an impact on how they view women#go jerk off and stop being obtuse about this!#total side note but everything I've ever read about Euphoria#makes it seems like a god awful show lmao#feminism#queued

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something that really aggravates me is tech bros like "lulz, you people just don't know how to use LLMs, that's why ur mad at them." But 1.) if something needs like, training in order to be utilized properly, it shouldn't be marketed to the average Joe in fucking TV commercials as an all-knowing machine that they can rely on for anything and everything with a mere click of a button and 2.) the techbros just ignore how people figured out that you can very easily manipulate the responses the chatbot gives you! But we're supposed to pretend that doesn't exist and isn't a serious problem with this tech lol

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

I actually think an underdiscussed solution to the male loneliness epidemic is for lonely men to stop killing people. I think if lonely men didn’t kill people because they felt entitled to the love and attention of others that would really do a bangup job of helping male loneliness. Perhaps they could even make friends with a woman without thinking that if they’re nice to her 3 times they deserve sex from her. Just spitballing here.

#remember folks: men commit 97-98% of mass shootings#I remember pointing that out and a man yelling at me for it#so that shows how open they are to this conversation lol#queued#feminism

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I'm just going to cut and paste this meme I made whenever someone who didn't vote for Hillary in 2016 screams at someone for pointing at the blood on their hands

811 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so fucking chicken shit for the conservatives on the Supreme Court to keep being like "well let's allow the Trump administration to keep potentially violating the law while lower courts decide the final word on whether or not this is actually illegal <3 " It's like cops allowing a robber to keep stealing from someone else's house until a judge signs a final form saying he's committing crimes

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's episode of insufferable attention whores features the left's favorite rape apologist:

(Link to thread)

And these are the people who wonder why they never win anything lol. Like yeah making your entire personality and political identity that of an edgelord 7th grader who realized he’ll get a rise out of his parents by saying really obviously ugly things is really unappealing to anyone who mentally progressed past middle school

Really, how is this functionally any different from a Republican wearing an offensive T-shirt or MAGA hat to trigger the libs? It’s not. Same thing with the Hasan stans screaming "it's just a joke omfg" on twitter. Republicans constantly deflect criticism against their obviously offensive statements with "omg libs can't take a joke XD"

161 notes

·

View notes