SCIENCE STUDIES, SPIRITUAL PRACTICE AND EXPERIMENTAL ART

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Documentation of ‘The Crocodile’ exhibition at Luna Elaine project space, London. New work by Matthew Drage, Miriam Austin, Paul Gwilliam and Al Page.

0 notes

Text

‘The Crocodile’ a short story by Dr. Boris Jardine written to accompany the exhibition of the same name at Luna Elaine Project space, London.

The Crocodile

He thought of the place first: a ruined chapel on a hill. But could there be a hill in this kind of countryside, which was not quite flat, but still conjured big skies and only occasionally went above sea level? Maybe a mound then, or even just a more open or exposed piece of land surrounded by woods and marshes. It was important to conceive the whole event, to grasp all of the interactions and developments, and this question of what the place would look like bothered him. How could he write a script or characters if he couldn’t even picture the chapel itself? Then he remembered the phrase they had given him: The sea is the most pure and the most polluted water.

The game would take place on board a ship. This was a fine conceit. Everything that could happen, could happen on a ship. The question of boundaries was solved, too, because anyone who left the ship would be drowned, or at least would need to be rescued. There was the problem of hierarchy, but that could fall out during play. They might be going somewhere, and could speculate about what kind of landfall they would make – presumably it would be an uninhabited island and the game would continue in more or less the same way. At the top of the document he wrote the words ‘The Ship of Fools’ and quickly sketched out a scheme.

The next day, after lunch, they set out, turning from the road down a track marked ‘fp’ for footpath. Soon the group fragmented and he found himself ahead of the others. To the left was the long straight drainage cut, visible only by the thick bulrushes that encased it. To the right – ancient by comparison – was a small stream that ran alongside the path, separating them from cows grazing on fields that led to a dark wood. Much further away, the white golf-ball dome of the nuclear power station rose above the treeline. He knew from the map that the chapel would be on that side, and looked out for the crossing.

/

He stood waiting at the fence. It was only knee-high but he wanted them to go in together. The ruin itself was slightly larger than expected: two walls still stood making a kind of exposed corridor; at the far end the modern brick of the pill-box. From where he stood the power station was in full view, but the sea itself was concealed by the long bank that ran north to south along the coastline. The machinery of the sluice centred the view, heading off the drain and penetrating the bank. He had seen a few mushrooms in the field, vetch and clover but not much else. The others arrived in a straggly line.

‘Michael –’ But he raised his hand to interrupt. They mustn’t break the game, or, at least, they would go as far as they could without doing so. Cub was the first to step over the fence, careful to avoid contact in case it was electrified. The others followed and they clambered up together into the chapel. Rubble from the walls was piled up high. The question of value detained him briefly: these were the stones from which the mediaeval chapel was built, and yet they lay around with nothing to protect or organise them, or to mark out their significance. Were they just stones again? He thought of taking one for his museum, but they were too big. He kicked a few into the chapel and went on to the door of the pill-box.

Cub was already inside, standing in a dark corner. He could hardly discern her, and when he looked out

through the tiny portal he was temporarily blind to the room. Cub struck something metallic against the wall, and gave a little shout. She struck again and advanced on him. Her face now came into the light and he smiled at her. She stopped but did not respond.

Outside, Bird, Snow Leopard and Friar were aimlessly exploring the chapel walls. Rat and Spirit crouched opposite each other, more or less at the entrance to the ruin, sorting through rubble.

Rat looked up and said mechanically, ‘With a deer’s form surrounding her – what’s next?’

Spirit completed the phrase: ‘With a deer’s form surrounding her, she labours at her task.’ She held up a large dark flint nodule. ‘But I’m a spirit, not a deer.’

‘I think it just means that you have a body – I mean, that we have bodies. Corporreal form.’

Spirit looked dismissively at Rat. ‘This is a body.’ And she threw the flint, hard, at the wall behind his head. A few pieces shattered off but the bulk of the nodule dropped heavily onto a pile and rolled down a little.

Bird came and stood over them. ‘Have you two selected the stones?’

‘Spirit smashed a good one,’ said Rat, not looking up.

Having ventured outside the walls of the chapel, Friar and Snow Leopard were busily picking the tiny flowers that grew here and there.

‘The purple ones that grow in a kind of neat line are called

vetch,’ said Friar, ‘we’ll need plenty of that for the ritual.’

Snow Leopard either didn’t hear or ignored him, and kept picking anything she could see, including a few clumps of grass.

‘Where are we going, Mr Friar.’ ‘I mean, you’re a scholar, but a scholar of what? Scholar from where?’

‘I’m not a scholar, and we don’t know where we’re going,’ said Friar simply, ‘that’s the point.’

Inside the pill-box, Cub remained silent as she lifted the small piece of rusted metal to his lips. He shook his head and turned away to look out of the letter-box window. He could see the power station and not much else. Who ever came here? Why had they come here? Cub poked him in the side with her new talisman.

‘You need to put this in your mouth.’

‘No I don’t. Not yet anyway. We’re still exploring the ship, and also it doesn’t mean anything if the others can’t see it.’

‘Why are you talking like that? We’ve been here for months, and how do you know what anything means?’

‘Ok, I mean – the point is that it’s not time yet, for that.’

‘Let me see.’ And she pushed his head aside with hers. There was just enough room for them both to look out.

‘What’s that then? Is it The Enemy?’

‘I think so,’ he said, and held up his hand, finger

extended like a gun. ‘P’chow.’

Cub’s hands made binoculars and she reported in hushed tones, ‘they have something in there – in the dome. Some kind of memory system. It’s important.’

‘Is that why we have no memory, because they keep it locked away from the citizens?’

Cub stuck her arm through the gap and shrieked as Snow Leopard thrust plants into it from the other side.

‘Take these into the belly of the beast!’ shouted Snow Leopard, ‘the belly of the beast!’

Friar’s nervous face appeared directly in front of them, peering in at the window.

‘What’s in there?’ he said, and went off in search of the entrance.

Rat and Spirit stayed in place, picking through the stones, while Bird and Friar walked into the pill-box together.

Bird groaned: ‘what’s that smell? Jesus.’

‘It’s a dead fox,’ said Cub, and pointed in the darkness. ‘I think it’s pretty badly rotted. But you get used to it.’

Now Snow Leopard was alone outside. She looked around and saw some people walking along the path towards the sea wall. They didn’t look up to the chapel but she felt watched. The few plants she had picked looked ragged in her hands, and she dropped them, brushing off the remaining bits and pieces

that clung to her skin. It was not warm but she took off her coat, and then her jumper, leaving only a thin vest to shield her from the breeze that whipped up the hill and followed the contours of the dilapidated walls. What were the others doing? Probably messing about to no purpose. She instantly regretted the thought and identified Rat as a possible companion. They could probably take control of the situation.

The pile of stones that Spirit and Rat had been assembling and sorting was now complete, or at least it had an obvious logic to it: a large base of flints supported increasingly small pieces of rubble until it reached an awkward point about a foot off the ground. They sat in silence for a moment before Spirit spoke:

Now she weeps, and now rejoices;

Now she weeps, and now is judged;

Now is judged, and now she dieth;

Now is born, with no way out for her; in misery

She enters in her wandering the labyrinth of ills.

‘Shouldn’t the others have heard that?’ said Rat.

‘It doesn’t matter does it? He just said that one of us should just say it when the pile was finished.’

‘But we forgot to to wait for the flowers to be put inside.’

Spirit grasped a large clump of straw that grew next to

her and yanked it out of the ground. She took some of the top stones off the pile until there was a small well, into which she placed the straw before replacing the stones she had removed. Pieces of straw now stuck out of the side of the pyramid.

They stood and walked over to the entrance to the pill-box and positioned themselves either side like sentries. Spirit began to sing a plain high note, and after a few seconds Rat joined in with a wavering lower note. They continued like that for the length of a long breath. Bird came to the entrance, and looked out at the pile of stones.

‘Did you say the labyrinth bit?’

Rat and Spirit looked at each other but didn’t respond. Friar bumped into Bird’s back. ‘Get out would you.’ They stepped out into the centre of the ruin, all except Cub. Rat and Spirit kept their stations.

Bird spoke briskly: ‘Cub’s staying inside. Says she has scurvy. She’s going to keep a ship’s log and look out of the porthole at The Enemy.’

Friar’s face contorted into disparagement. ‘Where’s Snow Leopard? Did she go overboard?’ Nobody spoke. Friar looked around and tried to assert himself: ‘Now she weeps, and now rejoices; Now she weeps, and now is judged –’

‘I already said that bit,’ said Spirit, and Rat looked sharply at her, then at Friar, who continued pompously:

Now is judged, and now she dieth;

Now is born, with no way out for her; in misery

She enters in her wandering the labyrinth of ills.

He strode up to the stones. ‘We’ve landed,’ he said, waving his hands at the pile. ‘We will form a new society here, in this land of God. Once, we were on board ship, but now the body of the ship has become like unto the sea itself, this place –’ and here he planted his foot roughly onto the stones, displacing most of them and exposing the straw ‘– is a pristine kingdom. Let no man or woman bedevil it with sin!’

While Friar was speaking Snow Leopard walked up behind him, carrying the small piece of metal that Cub had found, which she must have passed out through the little window. She reached around and placed it into his hand. ‘You need this,’ she whispered, stepping out to face him. He held the piece of metal up and squinted at it. Bird said ‘tell us what you can see,’ and slowly they all spread into a circle round him. With his free hand Friar removed a piece of paper from his pocket and awkwardly unfolded it with his fingers. Before he could start reading, the boy reached out and took the metal from his hand. Holding it up to his face he began to speak in a low, chanting voice. Haltingly, they all tried to speak with him:

O Father, see!

Behold the struggle of ills on earth!

Far from Thy Breath she wanders!

She seeks to flee the bitter Chaos,

And knows not how she shall pass through.

Wherefore, send me, O Father!

Seals in my hands, I will descend;

Through Æons universal will I make a Path;

Through Mysteries all I’ll open up a Way!

And Forms of Gods will I display;

The secrets of the Holy Path I will hand on.

Just as the last of them tailed off there was a sudden cry from the pill-box. He dropped the metal fragment and sheet of paper and ran towards the door. ‘What’s happened?’ Cub was there and quieted him with a gesture. He came in and shouted something but the odd silence stopped him. Cub was pointing to the little window of light, through which they could see a tiny figure cavorting up against the sea wall. They crowded up to see more clearly, but there was only room for two at a time.

The dome of the power station made an absurd abstract backdrop for Snow Leopard, who was now standing on top of the sea wall with her arms stretched out to either side. Further out behind her – probably quite far out to sea – dark clouds brought in the storm. Even further out, a large ship rocked at the centre of its

own world, though no crew walked about on deck and no one slept in the numerous cabins whose portholes were closer to sea level. Snow Leopard plunged her head down into the hard, frothy water; salt spilled into her nostrils and a black sound buffeting her ears. The hum that had in fact been present throughout the game now grew and its origin was obviously the power station. His hands grappled with the stepped sides of the window. Just outside, to the left, a large metal bracket secured intertwined strands of metal that swept away towards the sluice. A vibration shot back along the length of the cable towards him and he sprang backwards into the others. Someone tripped and fell and a crowd of concern formed. He muttered an apology and ran out into the ruin, then out into the field towards the wall. When he reached the top he was momentarily baffled by the sea. It was not blue, but a mottled, sick, greeny-grey. Snow Leopard was just out beyond the groin that must contain the sluice pipe, disgorging fresh water from the new cut into the sea. He jumped down onto the beach, skipping over the different sizes of stones and flotsam that had arranged themselves into rough strata. He called out to Snow Leopard, and she began swimming slowly back towards him. He looked back and saw that the others were coming up over the sea wall.

/

Only Friar was not among them. He had stopped to pick up the metal fragment, whose crazed surface and vague remnants of old lettering had detained him as the others fled. Pressing it into his palm he had glanced up to the point at which the top of the pill-box and the wall of the chapel met. There was a way up, and he climbed slowly onto the promontory. The top of the chapel wall was just within reach, and growing from it was a tuft of some grassy plant that he could not identify. Attached to this was a small bundle of fish tied around with a black band. Some old ropes strung about gave him a hand-hold and he pulled himself up, reaching for the fish. His fingers scraped against the wall, nearer and nearer to the bundle, and he jammed himself into a painful position that nonetheless held him firm. The only things above him now were the long stately flag with its embroidered moon insignia at the mast end and the sprig of shrubbery that balanced somehow on top, its pale mask keeping watch. He reached up, grasped the bundle and started cutting with the improvised knife.

SSEA Press 2018

Edition of 25

Boris Jardine

0 notes

Text

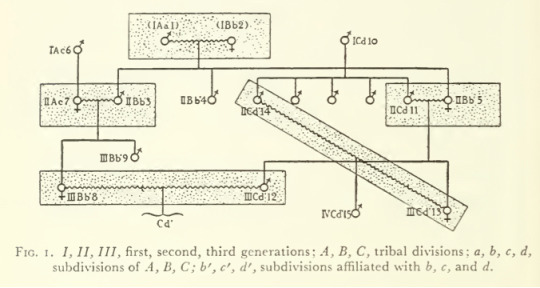

Kinship Bibliography by Dr. Jenny Bangham written to accompany the exhibition ‘The Crocodile’ at Luna Elaine Project Space, London

‘The Crocodile is … a spectre that haunts our games. It swims or slides or crawls in and makes something that was just pretend into something real. We become much smaller in ourselves. We are the birds that clean its teeth. But the crocodile is not a pristine kingdom. We think it could be some great vision of failure, it is magnificent. It is the reason we are friends and the image that makes our love of Avery so very sharp. We look above and see its great jaw but I think we sometimes worry it does not exist and we are just sitting on the ground.’

—PG

_______

‘Kinship: Relationship by descent; consanguinity (late 18th century); In cultural anthropology (late 19th century): The recognized ties of relationship, by descent, marriage, or ritual, that form the basis of social organization.So attributive and in other combinations, as kinship category, kinship group, kinship structure, kinship term; kinship system n. the system of relationships traditionally accepted in a culture and the rights and obligations which they involve.’

—OED

_______

The term ‘kinship’ refers to affective, cultural, narrative, and legal practices that structure close human relationships. It is also an anthropological concept, which has been used to define and study human life, and which has been questioned and reinvented several times in the field’s history. During the 1980s the concept of kinship was apparently undermined by theorists who worried that when anthropologists saw ‘kinship’, they were in fact seeing echoes of their own Anglo-American versions of human relations. Earlier critiques of biological essentialism gave way to the radical idea that the entire concept of kinship might be a modern Western projection. Against the backdrop of discourses in Europe and America about single parents, working mothers, “blended families”, abortion rights, and new reproductive technologies, the central issue became the role of biology in defining kinship. Eurocentic ‘biology’ was now seen as ‘cultural’, like any other performative aspect of kinship. Kin could be made through the rejection of ‘biology’ and ‘blood’, as well as through their evocation.

The following readings deal with histories of kinship both as a theoretical concept and social category. The first collection deals with the ways that kinship has been defined and contested by anthropologists. The second with the social, technological and legal changes since the 1980s that have shaped notions and practices of kinship in Europe and North America. The final collection deals with the complicated relationship between kinship and ‘biological relatedness’, especially the involvement of ‘blood’, as a metaphor and ritual.

_______

One

Bamford, Sandra, and James Leach. Kinship and Beyond: The Genealogical Model Reconsidered. Berghahn Books, 2009.

Franklin, Sarah, and Susan McKinnon, eds. Relative Values: Refiguring Kinship Studies. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2002.

MacCormack, Carol P., and Marilyn Strathearn. Nature, Culture and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Rapp, Rayna. “Toward a ‘Nuclear Freeze’? The Gender Politics of Euro-American Kinship Analysis.” In Feminism and Kinship Theory, edited by S.

Yanakisako and J. Collier, 119–31. Stanford University Press, 1987.

Sahlins, Marshall. “What Kinship Is (Part One).” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17 (2011): 2–19.

Schneider, David. A Critique of the Study of Kinship. University of Michigan Press, 1984.

Schneider, David. American Kinship: A Cultural Account. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

Wilson, Ara. ‘Visual Kinship,’ History of Anthropology Newsletter 42 (July 24th 2018).

From: Boas, Franz, ‘The Social Organization of the Kwakiutl’ in Race, Language and Culture, The Macmillan Company, 1940. Discussed inWilson, 2018, above.

Two

Franklin, Sarah. Dolly Mixtures: The Remaking of Genealogy. Duke University Press, 2007.

Helmreich, Stefan. “Kinship in Hypertext: Transubstantiating Fatherhood and Information Flow in Artificial Life.” In Relative Values: Reconfiguring Kinship Studies, edited by Sarah Franklin and Susan McKinnon, 116–45. Duke University Press, 2001.

Nash, Catherine. Of Irish Descent: Origin Stories, Genealogy, and the Politics of Belonging. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008.

Nelson, Alondra. The Social Life of DNA: Race, Repatriation and Reconciliation after the Genome. Beacon Press, 2016.

Reardon, Jenny, and Kim TallBear. “‘Your DNA Is Our History’: Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property.” Current Anthropology 53, no. S5 (2012): S233–45.

Sisters, TV series (2017–), Netflix; produced by Endemol Shine Australia. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6258050/?ref_=ttco_co_tt

TallBear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Thompson, Charis. Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Reproductive Technologies. 2005 MIT Press, Inside Technology Series.

Weston, Kath. Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Zhang, Sarah. ‘How a Genealogy Website led to the Alleged Golden State Killer’, The Atlantic, 27th April 2018.

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/04/golden-state-killereast-area-rapist-dna-genealogy/559070/

Three

Chinn, Sarah E. “‘Liberty’s Life Stream’: Blood, Race, and Citizenship in World War II.” In Technology and the Logic of American Racism. London and New York: Continuum, 2000.

Copeman, Jacob. Veins of Devotion: Blood Donation and Religious Experience in North India. Studies in Medical Anthropology. New Brunswick, N.J:

Rutgers University Press, 2009.

Guglielmo, Thomas A. “‘Red Cross, Double Cross’: Race and America’s World War II-Era Blood Donor Service.” The Journal of American History 97 (2010): 63–90.

* Haraway, Donna. “Universal Donors in a Vampire Culture: It’s All in the Family: Biological Kinship Categories in the Twentieth-Century United States.” In Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature, edited by William Cronon, 321–66. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1995.

Johnson, Christopher H., Bernhard Jussen, David Warren Sabean, and Simon Teuscher, eds. Blood and Kinship: Matter for Metaphor from Ancient Rome to the Present. Berghahn Books, 2013.

Lederer, Susan E. “Bloodlines: Blood Types, Identity, and Association in Twentieth-Century America.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19 (2013): S118–29.

Mazumdar, Pauline. “Blood and Soil: The Serology of the Aryan Racial State.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 64 (1990): 186–219.

Reddy, Deepa S. “Citizens in the Commons: Blood and Genetics in the Making of the Civic.” Contemporary South Asia 21 (2013): 275–90.

Rudavsky, Shari. “Blood Will Tell: The Role of Science and Culture in Twentieth Century Paternity Disputes.” University of Pennsylvania, 1996.

Spörri, Myriam. Reines Und Gemischtes Blut Zur Kulturgeschichte Der Blutgruppenforschung, 1900-1933. Universität Bielefeld: Verlag Bielefeld, 2013.

Weston, Kath. “Kinship, Controversy, and the Sharing of Substance: The Race/Class Politics of Blood Transfusion.” In Relative Values: Reconfiguring Kinship Studies, edited by Sarah Franklin and Susan McKinnon. Duke University Press, 2002.

Whitfield, Nicholas. “Who Is My Stranger? Origins of the Gift in Wartime London, 1939-45.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19 (2013): S95–117.

______

‘I am sick to death of bonding through kinship and “the family”; and I long for models of solidarity and human unity and different rooted in friendship, work, partially shared purposes, intractable collective pain, inescapable mortality, and persistent hope. It is time to theorize an “unfamiliar” unconscious, a different primal scene, where everything does not stem from the dramas of identity and reproduction. Ties through blood-including blood recast in the coin of genes and information--have been bloody enough already. I believe that there will be no racial or sexual peace, no livable nature, until we learn to produce humanity through something more and less than kinship. I think that I am on the side of vampires, or at least some of them. But, then, since when does one get to choose which vampire will trouble one’s dreams?’

—Donna Haraway, * above, p. 366.

0 notes

Photo

A Walk in the Woods devised and performed by Matthew Drage and Miriam Austin as part of Luppercalia at Bosse an Baum Gallery, London 2016

0 notes

Photo

Rebirth Ritual at Bosse & Baum Gallery, London as part of the Exhibition Lupercalia by Miriam Austin, 2016

0 notes

Photo

Documentation of the Ritual Enhancement event at Chisenhale Gallery, 2014

0 notes