Nepal as a Peace Corps Volunteer: March 6 2015 - May 21 2017 Qualla Boundary of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation: June - August 2013 University of Havana: February - June 2012 Jordan, Israel, Egypt, and Palestine: December 2011 - January 2012 The contents of this Web site are mine personally and do not reflect any position of the U.S. Government or the Peace Corps.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Another favorite strips of artivism in Kathmandu - public health, style!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favorite stretches of street artivism in Kathmandu. (Notice the "love is love" part near the end!)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The view from our balcony into the Madi Phant on the first morning, filled with clouds, and the second morning, cleared out from last night's storm.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two years of changes, and the familiarity that remains

I was greeted with fresh honey combe, a plate full of of dhal baat, and a goat cutting. The smells of the moist soil in the monsoon season, the rich chorus of crickets and birds and rice cookers, and the sight of the dark green rolling hills felt like a warm blanket welcoming me back in.

Coming back to my site (what PCVs call the community they live in) has been, for lack of a better word, surreal. When I left site, two years and two weeks ago, I left in a rush. My Zayda (grandfather, in Yiddish) back home was sick, and so my family and I decided that I would COS (Close of Service -- used interchangeably as a verb and a noun among PCVs) early to see him. The morning of the very day I was heading up to see him, after two years, he passed away. Even now, two years later, the memory of his passing before I got to see him feels heavy and sad.

In the rush of COS-ing in a week, I remember coming to terms with the feeling that I was trading closure at my site for closure with my grandpa. My last week here in Nepal was a frantic blur of packing and goodbyes and finishing up medical exams and paperwork for Peace Corps staff. Time moved quick, after two years of becoming accustomed to time that moved slow.

Now, as I sit here and look out over the Madi Phant (the valley in between Madan Pokhara, my site, to the South and Tansen, the district capital, to the North), I'm comforted by the familiarity that remains in this place. Chapal (sandals) are scattered throughout the house in pairs, as they once were, welcoming my feet to find some cushion from the cold cement floor. The layout of the kitchen garden, with the papaya trees soaring above the light green orange trees, crawling bean vines, and low-lying elephant leaf plants, is the same as it was two years ago. And our water buffalo, as always, is grunting in anger or hunger or whatever else compels her to sing her morning blues.

I haven't even been here for 48 hours, and already the memories are rushing back. After my first morning dhal baat, I went with my aama to the monthly aama samuaa baitak (mother's group meeting) and was welcomed with warm smiles and an unbroken pattern of reading through their money ledger -- an implicit acknowledgement that I'm enough of a "normal" presence around here for them to stick to their routine (which I appreciated). A later gumnu (meander) around Tansen brought me past the medical pasaal (local pharmacy) where the owner laughed and asked if I remembered the time I brought my cat there for an x-ray of his foot (which I had forgotten!), then to the "Himalayan Organic Coffee" shop that held (holds) little treasures like dried ginger and dark roast coffee beans and chocolate digestive biscuits that were always a welcome deviation from the regular dhal baat, and then the print shop where I always printed and scanned by absentee ballots back to the States. After waiting an hour in the bus park for the bus to get filled (which is often more of a prompt for a bus to leave than any specific time on a clock), I came home to dinner with my aama (mom) and bua (dad), which was filled with an ease of simple coversation and smacking lips and looking out over the valley filled with the house lights that always reminded me of fallen stars.

Being here, even for two days, has been such a beautiful reminder that memories are held in space -- and the topography and climate and people and the sounds and smells within -- patiently awaiting us whenever we're ready for them.

Meanwhile, just as I've changed over the past two years, there are small markers sprinkled around here that remind me that I've been gone for as long as I was ever here. The most glaring change is that of my family structure - my bahini (younger sister) is now married and living with her husband and his family down in the Terai (the plains of Southern Nepal), my dai (older brother) is now living and working on a pig farm in South Korea (and is only one year into a five year work contract), and my bhai (younger brother) has gotten married and now spends more time in the house with his new wife, my buhari (younger brother's wife). The steep walking path to my cousin's house has been paved, and the beginning stages of paving the big road up to the radio station are in place. A new veggie shop has opened up near my cousin's store in Tansen, and a new hotel is open for business at the bus park. Our house is twice the size, with twice the subhida (amenities) as before -- with WiFi in the house to enable my family to more easily talk with my brother in South Korea and my sister at her husband's home in the Terai, a pump to bring running water up to the third (!) floor where the kitchen now sits, and a personal fridge in the kitchen next to the 55,000 NPR (~ $550) set of wooden chairs and table that replaced the metal set we once used. And the faces of all the little ones I loved have changed as well -- Kris (the baby who was born to my friends at the fruit shop 3 years ago) is now walking and talking and trying to carry around my big hiking backpack, Amrika (whose mom sometimes does day labor for my family) has gotten taller and her face leaner, and Angie (the younger sister of Prijma, who came to Camp GROW and whose family is related to us through our grandpa's brother) has replaced her love of goats for a newfound love of kittens. Even though I know it's been two years, it feels as if time has played a trick on me, and all of the changes have happened overnight.

Meanwhile, the geo-political identity of my site has changed as well. As Tansen grows more developed and the country as a whole works to decentralize development out of Kathmandu, VDCs (Village Development Corporations, somewhat like county lines) have been dissolved. Madan Pokhara has become a part of Tansen Nagarpalika (municipality), as have the surrounding areas, Thelgha, Arghali and Bharangdi. Our house and land khorr (taxes) have increased from 150 Rs/year to 500 Rs/year, and we had to pay an additional 8,000 Rs to an engineer to make a naksa (map/blueprint) of our house -- something which I believe is both associated in part with Madan Pokhara becoming a part of Tansen and with the expanded size of our house. Change is happening, in big and small ways, in this community and throughout the country as a whole.

Now, as my eyes linger on the top of the Himal poking out from above the Madi Phant that last night's storm made "sapha bhayo" (clear), and I listen to my buaa "moi parne" (churning the buffalo milk into a liquidy yogurt) from his spot on the balcony a few feet away, I'm warmed by the sun to the East and by the way this community has graciously welcomed me back in. I and this community have changed a bit, but/so/and I still feel as happy to be here as ever.

On to day 3!

0 notes

Video

One of the aunties in Madan Pokhara sang a song at the Damkada stage about all of the trouble that monkeys cause in the village. What a great video! I can see Jhabindra sir (my counterpart) in the back, as well as the Head Sir of the Damkada Government School, a few Female Community Health Volunteers, and a variety of other familiar faces. Makes me miss my site!

0 notes

Text

Nepal needs an extended TPS

This week, the Department of Homeland Security officially announced that it will end Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for the almost 9,000 Nepalis living with TPS in the US.

According to the press release, the "disruption to living conditions in Nepal" isn't substantial enough anymore. But I'd call it pretty "substantial" when thousands of people across 14 earthquake-effected districts are still living under tarps, piled multiple families into homes, and/or unable to work because debris and boulders cover their farm lands...wouldn't you?

For more, check out the Nepali-led NY-based NGO Adhikaar, a March 2018 report by the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, an article by NBC news, the official press release by DHS, and some photos I took from Lantang valley, just a year ago -- which was two years after the earthquake.

0 notes

Video

youtube

This video is a really powerful depiction of the sexism faced by women across Nepal, and makes me think of all my friends back in Nepal who are moving through the process of/continuing to live in arranged marriages.

Not all arranged marriages are negative experiences for the women, but this video does beg the question: what practices do we consider “normal” that are actually deeply rooted in sexism or some other form of oppression of non-dominant identities?

0 notes

Text

Waxing and Waning

From “when i sing along with you” by Zan Romanoff:

On the first night of Hanukkah, the moon is close to full, and we light one candle.

The next night, the moon turns its face from us, and goes a little bit darker, so we light two.

On the last night, there is almost no light left. We light eight candles. We make our own brightness. We put hanukkiot in the windows to publicize it: a great miracle happened here. And we remind ourselves, miracles don't come unless we rise up to meet them. Boots on the ground, feet in the water. We have to march forward to find the world we're trying to live in. I know last night was a complicated victory, and too close for comfort. I know it was won the backs of people who are tired of carrying. I'm not-- I don't want to claim anything that doesn't belong to me. All I know is that again and again I'm grateful, at least, for the tradition that I live in, which insists that we be our own light in the darkness. That we remember that we have been lucky. That we bless the forces that have brought us again to this season, and prepare ourselves to do the work that will bring us to the next.

0 notes

Link

Gorgeous words from a friend in Nepal -- through which you really get a sense of life nestled in the hills, where nights are getting colder and work in the fields more intense with the harvests.

“Well, it certainly has been a little bit since I sat down to write y'all a little life update from the hills. As ever, much to report. The change of the seasons is upon us again! Nights turning crisp and cold, and stars overhead now exposed and gleaming, no more monsoon thunderclouds to hide them away. The harvest too has mightily begun. Whole rice paddies harvested in a fraction of the time it took to plant them, stalks laid out in the sun to dry before being carried dutifully home on villager backs. Kodo or millet also being picked, the tasseled heads cut first, the straw (winter food for the ruminants) soon after. Once the harvest is done, then begins the processing! Heating up - literally translated - the kodo by beating it with long sticks to loosen and liberate the seeds from the tasseled fibrous top. Stomping on it with feet (my favorite job and one didi now saves for me) to remove the chaff. I leave the winnowing to her though. Yes, plenty of work in the fields for the post festival season.”

Read more on her website, and see some of the awesome nursery/yearround vegetable production/income generation projects that she’s doing with her didi (host sister).

With peace and a longing for the shortening days and chilly nights in the Nepali hills,

Rachel

0 notes

Quote

On the day when The weight deadens On your shoulders And you stumble, May the clay dance To balance you. And when your eyes Freeze behind The gray window And the ghost of loss Gets in to you, May a flock of colors, Indigo, red, green, And azure blue, Come to awaken in you A meadow of delight. When the canvas frays In the curragh of thought And a stain of ocean Blackens beneath you, May there come across the waters A path of yellow moonlight To bring you safely home. May the nourishment of the earth be yours, May the clarity of light be yours, May the fluency of the ocean be yours, May the protection of the ancestors be yours. And so may a slow Wind work these words Of love around you, An invisible cloak To mind your life.

“Beannacht,” which is the Gaelic word for blessing, by the Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue.

0 notes

Link

My third story published by the Peace Corps Stories website!

0 notes

Text

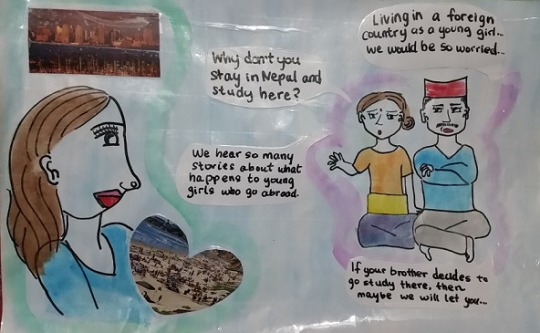

Kamishibai: Using Traditional Japanese Story Telling as a Tool for Girls’ Empowerment in Nepal

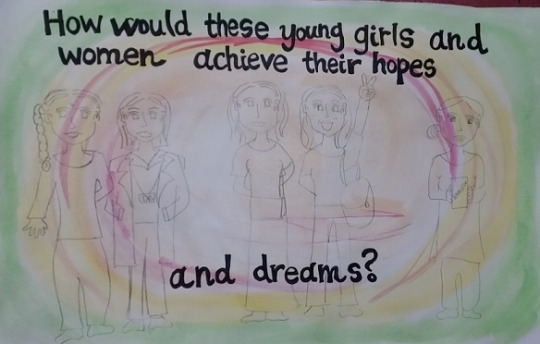

Rachel, a fellow PCV in my group, used a traditional Japanese story telling method throughout her service as an innovative way to teach youth about girls’ empowerment. Above is a photo of some of the students at our Camp GROW in Palpa in May 2016, when Rachel led a Kamishibai story telling session.

Below are photos of each page that she made, which she displays in a small wooden theatre that she made (shown above) as she talks through the story below.

Introduction to Kamishibai:

Kamishibai is a Japanese story telling method where there are visuals that engages the audience with active listening and participation.

There are three stories all together that will showcase the Nepali women and girls. The characters are Rakshya, Sabitra and Laxmi.

Story of Rakshya (1):

This story is about a girl named Rakshya who studies in class 8. She is an exceptional student. She enjoys going to school to be with her friends. Yet, the difficult news has arrived that this girl will not be able to go to class 9 starting in spring.

Story of Rakshya (2):

What could have been the reasons that made Rakshya's family decide the way they did about her schooling?

Possible answers include:

Financial reasons

Family expectations

Caste issues/bullying at school

School infrastructure problems (lack of water and sanitation, charpi toilets are not suitable for girls during menstruation, etc.).

Story of Rakyshya (3):

Rakshya wants to continue going to school. But she is also faced with the dilemma that her family has their hands full with house work, and that they need her home to take care of the chores. She is afraid that this will lead her to an early marriage, only taking her farther from her dream of one day becoming a doctor…

Rakshy is not sure who to turn to, or what to think.

Story of Sabitra (1):

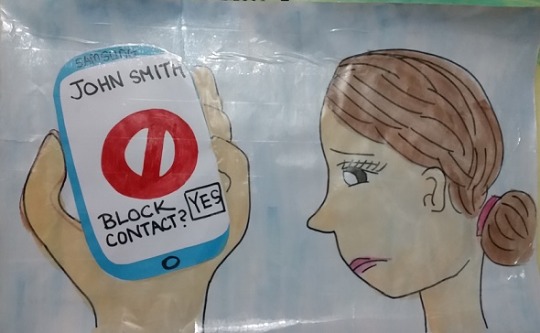

Sabitra’s husband is living in India and she lives with her in-laws, including a babu (boy) of four years old. She recently opened a Facebook account to keep in touch with her friends and husband, but one day an unknown stranger named John Smith added her on Facebook. He said he wanted to be her friend, and that he spoke English, and she wanted to speak English with this foreigner from another country.

“What a great chance to practice my English!” she thought to herself.

Story of Sabitra (2):

As days went by, the conversations became more personal and Sabitra started to get nervous about the conversations from John Smith.

(During this presentation, tear off the conversations with a sticker to show the audience, one by one, the conversations.)

Story of Sabitra (3):

Finally, John Smith told Sabitra that he had sent her a gift from the UK, and that it would be sent to her home. He also created a fake website showing the package on its way to India.

She grew very worried, yet she did not know who she could talk to. John Smith also said that she had to pay 40,000 NPR to pick up the package in her name.

Who to go to? Who to talk to? Sabitra felt like she could not talk to her husband about this. She decided to block John Smith, but was still unsure if the package was going to arrive at her doorstep, and if she would have to pay the money or not.

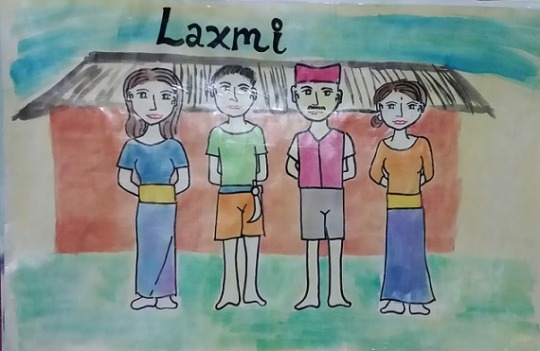

Story of Laxmi (1):

Laxmi is currently in class 12, and is a very bright student. Laxmi comes from a small member household, but they are all very active people in her village.

Her older brother, Suyog, is an active farmer in his village, following in his fathers’ footsteps. Laxmis’ aama is the Female Community Health Volunteer.

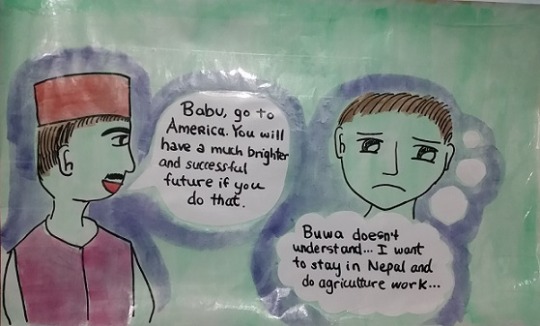

Story of Laxmi (2):

Laxmi’s brother, Suyog, has been facing a dilemma. His buwa wants him to go abroad to widen his horizons and also make money by working abroad.

Buwa admires his son's determination for agriculture work, but wants his son to have opportunities that the buwa never even dreamed of achieving.

There is constant pressure from Buwa to Suyog…but if only Buwa knew that Suyog is just not interested.

Story of Laxmi (3):

Laxmi, on the other hand, has a dream of going to the USA to study, and hopefully even find a job there.

She has no hopes of living in USA forever, but would like to learn new technical skills so she can bring all this new knowledge and information back to Nepal. She has also expressed to her family that if she does start working abroad, she can send money to her family. Yet, her family is not fully supportive of her wishes and hopes.

What do you think were some of the responses from her parents?

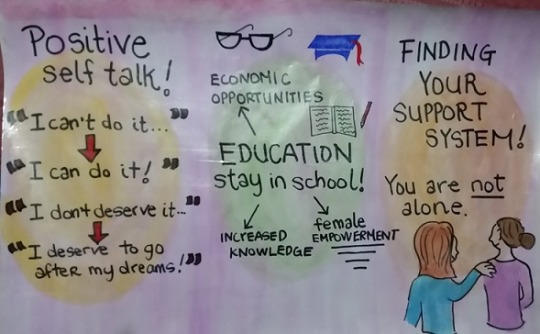

Tying it all together:

Today, you have met three different characters showing three different struggles.

One was the young girl Rakshya who had to discontinue her education after class 8.

Another was Sabitra, the daughter-in-law of the house, and an educated woman who wants to learn English, but she ran into online scamming.

Finally, there was Laxmi, who wants to travel abroad but is discouraged from doing so due to her gender.

Ending:

Situations like this can make it hard for girls and women to achieve their dreams and further their ambitions.

It is important that, no matter what challenge you face, you find your support system of a few people who you trust. Often times, we internalize our problems and think we cannot express them because we feel shameful, or we are afraid that talking about them would bring disrespect to someone else.

Many of these same issues are shared by other women and girls - you would be surprised by how many other people face these same issues!

So, despite your fears, it's important to reach out, because you are not alone, and your support system can help!

More about online scamming:

Online scamming can happen not only to girls but also to boys, men and women. With so many people having access to social media, it is important that everyone be careful when making friends with strangers online -- whether abroad or in your own country.

Online scamming can also come through news that seems "too good to be true." Watch out for those who are promising you “a better future,” such as ways to make money to help you and your family. This is a RED FLAG.

If online scamming happens, do not be ashamed! Just make sure to let someone know what is going on.

0 notes

Link

Interesting article about the pulls and pushes between India, Nepal, China, and the US. (I’ve copies and pasted it below, and have also included the link.)

The foreign policy of independent India is no different to that of East India Company it has come to despite so much of late.

India is in the process of rewriting its own history, the new writing purged of the biases of ‘paternal orientalism’ that supposedly characterized the earlier works of British historians of India like John Keay and Charles Allen. Shashi Tharoor’s most recent book, An Era of Darkness, for instance, is a scathing criticism of the British rule of India. He methodically shoots down every argument that the empire was in any way beneficial for India. A case in point: When the British East India Company was established in 1600, India accounted for 23 percent of the global GDP; when the ‘rapacious’ British finally left India in 1947, India’s share of global GDP had shrunk to under five percent.

Yet, interestingly, while India has been trying so very hard to get rid of the historical burden of the British Raj, the foreign policy of independent India is not much different to what the Brits practiced through East India Company. This is particularly true when it comes to dealing with countries in the region that were considered by the company as coming under its ‘sphere of influence’. Since Sikkim and Bhutan, two of the three countries at the core of this supposed sphere, are now firmly in the Indian camp, the recent Indian focus has been on securing India’s stranglehold in Nepal.

Revenge of geography

To be fair to the Indians, although geography isn’t quite destiny, it has always been the most decisive factor in the conduct of international relations. Have a close look at the geopolitical map of Nepal and the first thing you notice is that the country is bound by easily-accessible flatlands of India on three sides. In fact, in the map, the whole of the country appears submerged in the bigger Indian landmass. You see that only on its northern side is Nepal flanked by China’s Tibet Autonomous Region, the two countries separated by the enormous, almost impregnable Himalayan peaks. India was thus always going to have a decisive say in Nepal.

China knows this. This is why it has repeatedly told Nepali leaders that China is ready for closer relations with Nepal, but there is also no option for Nepal but to be in best of terms with India. China understands that it is futile to try to match India’s outsized but natural influence in Nepal. But what China wants to be able to do in Nepal, as in the rest of South Asia, is to thwart what it sees as growing American attempts (post Obama pivot) to encircle it in South Asia with the help of America’s democratic ally in India. China wants to retain enough sway over Nepal to ensure that the Americans don’t use India (and, by extension, Nepal) to make mischief on its Tibetan border.

That the US rather than India is the main Chinese concern in Nepal is evident in the recent pronouncements of Chinese scholars. I have personally asked many Chinese academics—who have in recent times made a beeline to Kathmandu to push President Xi Jinping’s signature One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative—if they are concerned about India’s coercive and rather exclusionary diplomacy in Nepal. The reply, always circuitous, is along the lines of: “The Indians are far too clever to follow American diktat”. In other words, we are concerned about growing Indian influence in Nepal only to the extent it allows the US, the sole superpower China is competing against, to push its agenda in Nepal.

But, again, following its resounding victory in the 1962 border war against India, China has never been insecure about India, a country the Chinese think of as rather inferior to them, both militarily and economically, and perhaps even culturally.

Since China is not directly competing for influence with India, it is comfortable with Nepal’s trilateral Nepal-India-China cooperation proposal, particularly the idea of linking the three countries with roads and rails. Such cooperation, it thinks, can help keep the meddling Americans out of Nepal. But for India any proposal emanating from Beijing is suspicious. In India’s reckoning, it is engaged in a zero sum game: only one of India or China can win the old geopolitical game in Nepal.

This is why there was a lot of hand-wringing in the South Block when Nepal announced its inaugural joint military exercises with China. The plan was that around 100 army personnel each from Nepal and China would together conduct anti-terrorism and disaster-preparedness drills. In the event, Nepal had to significantly water down the drills, downgrading it from ‘joint military exercise’ to ‘joint military training’ with the involvement of 25 soldiers apiece from Nepal and China. Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal and the Nepal Army top brass were under relentless Indian pressure to keep the whole thing as low-key as possible.

The Indians clearly feel that greater Nepal-China military engagements will undercut its influence in Kathmandu. But for Nepal, these military drills (or whatever you choose to call them) with China are important. It is an unmistakable signal to the rest of the world that Nepal does not consider itself as falling under the sphere of influence of any country, and that it has complete freedom to conduct its foreign policy.

Nepal’s efforts to improve its relations with China were paradoxically boosted following the 2015-16 border blockade, when New Delhi had tried to hijack the Madhesi movement to remind Kathmandu that it better not get too close to Beijing—or else. In the same vein, India does not want Nepal to sign up to OBOR initiative as it feels some components of OBOR impinge on Indian interests. But joining the OBOR is in Nepal’s interest; it is a potent means to ensure that Nepal will never again be blackmailed through coercive tactics like blockades.

Obey the nature

The Nepali leaders I speak to, from across the political spectrum, all know that Nepal is not in a position to antagonize India. But they are absolutely right that as a landlocked country, Nepal must learn to hedge its bets, and try to maintain a semblance of balance between the influence of India and China, even if the scale will always tilt towards India.

The best way India can respond to recent Chinese push into Nepal is by learning to treat its small neighbor with more respect; by according Nepal the dignity it deserves as a fully sovereign and independent country. The largest democracy in the world and the producer of some of the most potent symbols of soft power—Bollywood, IPL, an indomitable free press, to name just a few—India has a lot going for it. Other smaller democracies in the region naturally look up to and try to emulate India. If only India was more comfortable in its own skin.

0 notes

Link

Yesterday, on the two year anniversary of the April 25, 2015 Gorkha Earthquake, I spent the day walking around my community and reflecting on the earthquake.

I read one article, in particular, that I felt did a great job summarizing where the country currently stands. This article was written by Subhash Ghimire, who received his Masters of Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School in 2014.

Subhash explained that, in the last 2 years since the Gorkha Earthquake, less than 3% of the 887,353+ houses destroyed by the earthquake have been rebuilt.

This means that thousands of “people in the mountains and the hills…have braved two seasons of freezing winter and heavy monsoon under make-shift tents.”

And although the Nepali Government has promised a grant of roughly $3,000 USD to each victim to rebuild their homes, the earthquake victims must first get a building recommendation from a local engineer who can sign off on the project. (Unfortunately, it seems they didn’t consider the ubiquitous phenomenon of the brain drain, where engineers in low-income countries typically move abroad, or at least to the capital, and don’t usually stay in the rural and remote villages.)

And what about the engineers and other technicians hired by the Government of Nepal to help? Unfortunately, the article explained, over 60% of the technicians (engineers, etc.) hired by the National Reconstruction Authority to rebuild communities have resigned because of poor pay and insurance.

“To make matter worse, we are facing a dearth of trained masons to build the houses. Massive outflow of young men to the Middle East for employment has led to an acute shortage of manpower to undertake mega rebuilding. Almost 1,200 young Nepalis leave the country for better opportunities in the Middle East every single day. An investigative story published in Republica estimated that building quake-safe houses might take over 100 years in Kathmandu that has only 242 trained masons to rebuild about 4,200 quake-destroyed houses.”

It’s hard to be reminded, just weeks before my Close of Service, that there is still so much left to do in terms of rebuilding communities destroyed from the earthquake. But with such powerful voices coming from within (like the "Rebuild Kasthamandap" movement), and some attention from the broader international community, I’m hopeful for change to come.

Rachel

0 notes

Text

Finding great gratitude in the small.

Gratitude is found in the small things.

This past Tuesday, just seven weeks before my last day at site, was a day made perfect by many small, sweet moments.

6:00 -- It all started at 6:00 in the morning, when I Skyped with my family back home during their Passover Seder. With the clear morning morning and early time on my side, I took advantage of strong data signal to turn on the video camera and bring my American family on a video tour around our Nepali home, our water buffalo and goats, our garden. When I got to the chicken coop, where my host family houses 240 boiler chickens, my great aunt asked me “Are those….garlic?” I laughed, and later shared the story with my cousin Khuma, who smiled and said “Ayyyyy, aba Amrika ma lasun hidne sakincha, ke ho?” (Wooooow, so now in America, garlic can walk around or what?”) I understood the sarcasm in her voice, and she understood the sillyness of the story, and although the moment was short, it was unblemished by misunderstanding or delays or cultural differences (which often make humor and silliness hard in foreign languages), and thus equally shared and perfect.

7:30 -- The next hour and a half, I talked on the phones with one of my PCV friends, Liz. We joked about how her younger group’s relationship with my older group have shifted over time, spoke about her successful oyster mushroom projects that she started (using millet and mustard straw to grow mushrooms since her community is too water insecure to grow rice for the rice straw – really innovative!), and mused about how various PCVs cope with the inevitable highs and lows of Peace Corps service. Both having just read “Into the Wild,” we also spoke about our yearning to travel, reflecting on the reality that Peace Corps is an international experience that is book-ended by two big journeys, but is actually quite stationary for the majority of the two years. It felt affirming to talk through that small, yet fundamental, truth: Peace Corps is not for those who have wander lust. Peace Corps is instead for people who want to live deeply, fully, in one place, one small (usually rural and remote) village, for two years, and to learn the subtle nuances of that place during that long time.

10:00 -- After talking with Liz, I went upstairs and asked my aama if she could serve me my food early, since I was meeting a friend later in the day. I now understand, after nearly two years living here, that if I don’t ask to eat at a certain time, it could be as late as 11:00 when my whole family eats our morning meal together. Today, however, I ate early, and as I was finishing my meal, which included bamboo (a taste I mistook for mustard oil and despised during PST when it was served to me as a special treat on my 23rd birthday, but a taste I’ve now grown to enjoy) and potatoes (which I now know to expect as a staple of every meal until the monsoon rains break us from our dry season), my bua walked in, and I knew to say “maile khanna khaye chu” (I’ve eaten), acknowledging the obvious as a polite way to avoid the rude-ness of eating before the head of the household (him). After eating, I washed my right hand and brought our two empty water buckets down to the outside tap to fill up, knowing that our inside faucet dries up in the dry season. As I walked outside, exposing my neck and face to the hot mid-day sun, I turned my thoughts to the many host families of other volunteers, and many of my own neighbors, who have to walk 15-30 minutes to get water from a community tap. How lucky we are, I thought for what must be the five-hundredth time, to have our own private family tap outside, not to mention an inside faucet that works most (if not all) months of the year. Perspective is everything.

11:00 -- After bringing the filled water buckets back upstairs, I set off to walk down to Nayapati, the bus stop about a mile from my house where I catch all buses to Tansen, Pokhara, Kathmandu, or elsewhere. At Nayapati I met up with Chelsea, another PCV who was coming to my site to visit a worm production farm in my village. We walked at a quick clip back up the hill, past the cement resting point where I’ve sat dozens of times with older women who needed to catch their breath on the uphill stretch, past the water tank where old men often sit, past the school where the neighborhood kids usually play after hours, and then followed the advice of various neighbors who pointed out how to get to Durba dai’s (the worm farmer) house. As I walked past countless community landmarks, places that were indistinguishable and without meaning two years ago, I was reminded again and again just how well I know this place. How filled with memories every spot has become.

At Durba dai’s house, his wife Usha walked us through their farm, pointing out key steps of the worm production process along the way. She spoke clearly, but quickly, and I realized that I was able to follow her without much effort. After spending some time with our hands in the dirt, picking out the few worms that hadn’t buried themselves deep to avoid the hot, dry upper layers of soil, we went back to the porch to sit in the shade and chat. And, in typical Peace Corps fashion, Chelsea, Usha and I ended up spending the majority of the afternoon doing just that: sitting and chatting. By the time Chelsea and I realized (from our growling stomachs) that it was getting late, Usha had already begun cooking up an afternoon snack. And just like that, as graciously as if we were her own children, she brought over a hearty snack of two kodo ko roti (big round black flat breads made from millet flour), two bowls of sour yogurt, two bowls of tarkaari, and two glasses of sweet, milky chia.

As Chelsea and I sat there, happily munching on our snack in the shade, overlooking a field filled with banana trees and coffee plants and goats and vermaculture compost piles, I was filled with gratitude for the unrushed days that Peace Corps life affords, and the generosity of Nepali people. Not many other times in my life, I thought, will I have so much time to just sit, relax, and enjoy the passing of the day with the company of complete strangers. Chelsea and I ended up hanging out with Usha and her family for four hours that day.

3:00 -- After Chelsea left to catch a bus back to her own site, I walked over to the “balbalika ko karekram” (children’s program), where the President of the Children’s Club had invited me to come speak about the differences and similarities between situation of children in the United States and in Nepal. Although he had only invited me that morning, and barely mentioned where the meeting would be held, I knew exactly where to go – and, walking into the training hall on the top floor of the school, I was struck with memories of the very first meeting that I ever went to in that room, nearly two years ago, when I had been asked to introduce myself to all of the community leaders, and had stumbled my way through my previously-prepared (and practiced) 3-minute introduction in Nepali before quickly rushing to take my seat.

Today, however, I got up without notes, without much guidance, and spoke to the students for 30 minutes – easily sliding back into English when needed (and knowing which adults in the room I could turn to for help), but by-in-large being able to comfortably speak and share my thoughts in Nepali. I spoke about the existence of both public and private schools in the US (similar to Nepal), about school uniforms (usually not required at public schools in the US, although they are in Nepal) and school buses (usually available in the US, but not in Nepal), and about the minimum age to vote (18 in the US and in Nepal).

After speaking for a while, I encouraged the students to stand up and ask their own questions, and was thrilled to hear some really thought-provoking ones (asked by an equal number of boys and girls, which is rare), including:

How do you take care of young babies in the US?

What are the laws in the US about child abuse and child labor?

What are the differences in social services available to kids versus adults in the US?

What strengths does Nepali society have to offer that the US should learn about?

As I answered their questions, I felt confident, knowing that the students understood my Nepali (or most of it, at least) and that I was speaking from a place of deep understanding of both systems – something I would not have been able to do as well two, or even one, year ago.

4:00 -- After my part in the program ended, I walked the mile back down to Nayapati (to pick up some fruit I had forgotten that morning). The late afternoon sun glowed a soft orange on my closed eyelids as I slowly and easily made me way down the dirt road, knowing (without having to look) which sections of road had been expanded, which banks had been reinforced, and which water gutters had been built since I first arrived two years ago. I opened my eyes just as a group of monkeys, 18 in total, crossed the road, scaled the exposed roots of trees along the edge of the jungle, and made their way inside the tree-filled refuge. Although when I first got here, I felt alarmed by the warnings of my neighbors to watch out for the bhadr (monkeys), I now knew not to be afraid of them, and that if I simply continued on my way, they’d continue on theirs.

4:30 -- With a kilo of anar (pomegranate) in hand, I walked from Nayapati back up to the house of our ward’s Female Community Health Volunteer, whose father in law passed away 5 days prior. After having experienced two deaths in my host family over these past two years, I now know too well that the 5th day after the death is the first day for visitors to come and give their condolences, that I should not to do the “Namaste” hands since it was a time of mourning, and that I should make sure to pay respect to the wooden chair set up with a framed photo of the man who passed away. As I glanced over towards the wife of the man who passed away, I wasn’t surprised to see her hair down and unbrushed (a stark contrast to the usually neat bun or braid that most Nepali women keep), and her thin body wrapped only in a few pieces of white cloth with nothing underneath (the required outfit for the mourning family members for 13 days). Her gaze met mine, and I knew to hear the kindness in her predictable remarks on how my face has gotten fatter since two years ago, how “moto bhayera ramri bhaye cha” (you look so beautiful now that you’re fatter). Her comment, which used to make me feel uncomfortable in my first few months of site, now left me feeling complimented.

5:00 -- After about 30 minutes, I walked with my cousin back to her house, then sat outside with our hajurbua (grandfather) to de-shell dried beans that would become next week’s daal (lentil/bean soup). I enjoyed the lack of conversation as I sat with the 89-year-old, instead focusing on each crinkle of the dried bean cover crumbling in our fingers and ping as the beans reached the metal bowl. I wasn’t surprised to see my hajurbua, on multiple occasions, pause his de-shelling to slowly reach into the bean skeletons and extract individual beans that had been accidentally discarded – despite the fact that his eyes are failing him in his old age. I felt so comfortable, so in my place, just sitting there with him – and I felt so grateful for that comfort, because comfort is hard to come by in new places. But this place is no longer new to me. It is very much familiar, known, and understood.

At the end of the day, reflecting on these many small moments of understanding and comfort, I thought about how that these small moments are enough. They are what separate the recently arrived Rachel from the nearly COS’ed Rachel. They are what make conversations these days with host family and friends smoother, funnier, more honest. And they are what have made this place a home for these past two years.

In these next seven weeks, I hope to come to terms with the fact that the process of accumulating these many small moments of understanding has provoked a lot of personal growth in me – and that even though I don’t fully realize all the ways I’ve changed, that I will never be the same person I was when I walked into this village two years ago.

Now, as I hear the clatter of plates and bowls upstairs, I know it’s time to put my computer away, put on my shoes (no bare feet allowed), and walk upstairs for our evening meal eaten under the stars and the full, orange moon.

What a beautiful experience this has been, to find great gratitude in the small.

Rachel

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lessons Learned by RPCVs in Nepal

On April 4, a new trainee in Peace Corps Nepal’s group N204 asked the following question:

What did you learn in Nepal that was incredibly useful while you were there...but no application back home? Like I learned that you can wedge yourself against a mountain pass and hold an umbrella out so cattle wont throw you off. And I leaned that ants will not attack food stored atop a (leaky) kerosene stove. Any others?

Within minutes, answers began pouring in from RPCVs who served 30-40 years ago, to current PCVs serving in Nepal. Most of the responses, despite their variety, make me smile as they ring true to my own experiences here as a current PCV in Nepal, just two months away from my COS. And although responses are still coming in, here are the responses received in the first 10 days following the initial question:

Take warnings about rhinos seriously.

Keep your 2nd floor windows closed during the day as the chickens will fly in and crap all over your bed and perhaps lay an egg.

Don't chew rice.

Always be prepared for an unanticipated holiday.

If you want to write down the combo lock on the door post outside your dera, use Roman numerals - nobody can figure them out.

Just how much one can do without.

The actual difference between wants and needs. Our trunks were delayed between Delhi and Kathmandu so I couldn't take it out to my post, in fact I didn't have it until three months later. La, I had survived without all the stuff I packed in the belief that it would be indispensable.

Don't touch food with your left hand.

Don’t teach 4th and 5th graders that the word for baby chicken in English is "chick."

How to lipnu.

That I have a fairly high tolerance for dysentery.

Priming those awful stoves. I refuse to use white gas backpacking stoves for this reason - I feel I've done that enough for one lifetime!

Learned I was incapable of instantly switching between Nepali and Hindi. It took me a day or two to purge Hindi from my Nepali or vice versa. (Back in the days when summer travel between my post and Kathmandu involved speaking Hindi while walking across the inner Terai and then two days on Indian buses and trains.)

Flies are attracted to light. Rats like block soap.

How to bake brownies in a dekshi oven.

How to make soup from goat skin, lungs and intestines.

The concept of "juto" and associated prohibitions of the left hand.

Not taking anything larger than one-rupee bills into the real hinterlands, circa 1970 when three rupees was the standard day's wage, although sahibs were expected to be a little more generous.

Muddy water will settle out overnight and be fit for drinking, after siphoning and purifying, the next morning.

How to plow with water buffalo.

From the class 3 English book I learned that "Mr. Sherchan has three cocks."

Hiking a peak in chappals (flip flops).

To run in chappals.

Spitting tobacco juice on your feet while wearing chappals in the jungle during monsoon keeps the leeches off.

Sleep under a mosquito net so the rats don't run across you at night.

You can make dahi (yogurt) out of the sweetened Nestle powdered milk as long as you have a starter.

How to make a projecting microscope out if scraps- milk cans, blown light bulbs, chapels and cheap lenses.

Covering my cup with my left elbow while waving my left hand over my plate to keep flies away, and eating with my right.

If you want to buy something, be the first to arrive at that particular pasal and and make a bid. You will get the best price of the day. (Morning business. I think the Nepali word is “bahoni.”)

By reading TATA trucks, I learned to "work like a coolie and live like a prince."

Applied hygroscopic principles when trekking by holding a small container of salt to sprinkle on engorged leeches. Salt absorbed the moisture and the leeches melted like the Wicked Witch of the East when Dorothy soaked her.

Speak Nepali all the time with everyone - especially the didis (women older than you) - you will make friends everywhere you go. People will look out for you. I cannot count the number of times I could not hike all the way back to my village before dark and people took me in for the night and fed me.

To completely shower with my lungi on and then dress in front of onlookers at the dera without showing anything from shoulder to below my knee. This has come in handy at the beach, stateside.

How to make rotis (flat breads).

I have found no application for knowing how to order a toomba (millet-based Nepali alcohol) back home.

Bathing politely at the well.

I have never had to bribe an Indian border guard again since PC days.

Lipnuing/mudding the floors of my dhera.

Putting your right turn signal on not to turn, but to indicate that the oncoming bus can pass on your right.

“Rato mato, chiplo bato.” (Red mud, slippery road.)

Didi taught me how to make daal bhaat. But in the states my husband makes it. Also, of course, how to eat well with my hands.

That chickens love eating my spit (and snot).

That chickens are evil.

Surfing the Himalaya on top of an overloaded TATA truck.

Identifying parts of a goat in the dark using my teeth.

Drinking Urvashi out of a warm coke bottle (on top of a TATA truck).

Steering rickshaws after a long bout of tomba.

Calming rickshaw drivers who are concerned that a tomba laagyo baideshi (foreigner drunk from tomba alcohol) is steering.

Fixing chappals with matches and getting local matches to light in order to fix chappals.

Bathing with only two mugs of lukewarm water.

Using a cattle prod to keep monkeys out of the food supplies.

To put my food containers on a plate of water to keep the ants out.

Learning how to wear a dhoti.

Throwing a casting net.

Skills I've used but not nearly often enough: Making raksi, chang, and yes one time even toomba.

I learned many ways to refuse another portion of rice.

Make jaard!

You don't need to say dhanyabad (thank you) for every transaction and there is no equivalent reply for thank you.

How to outrun a charging water buffalo, then climbing a tree to evade him.

Chortens and behind gompas were go to places when explosive diarrhea struck.

How to estimate the age of a pile of poop by seeing how many worms appeared. Few worms -- fresh. Many worms – older.

Real business gets done when you show up at an Under Secretary's home before morning bhat, not at his office or an embassy cocktail party.

A dhera directly above the buffalos' and goats' shelter can be cozy warm in winter.

How to refill a disposable Bic lighter.

How to do 1 and 2 while squatting.

How to fiddle with the knob and simultaneously prop a shortwave radio at just the right angle to pick up a broadcast.

To sling snot, Nepali style.

How to properly peel & suck the juice from ukhu (sugar cane) using your teeth.

Always store your med kit in your metal foot locker, lest while you're away from post for a few weeks, the rats will chew through the plastic of the kit and leave chewed up condoms scattered around your room.

Deet eats through duct tape (and mosquito nets).

Always walk on the upslope side of a yak!

How to jovially discuss poo composition over dinner.

How to hold a container of drinking water above my face, lean my head back a bit and swallow a steady stream coming from the spigot without choking or dowsing my shirt.

Once a child can walk she is potty-trained.

Peeing while standing so no one notices!

You can lay your bedding in hot sun and the fleas will flee.

The way to get rid of udus (bed bugs) in a rope bed is to submerge it for a sufficiently long time, weighted down with stones.

A bokha (un-neutered male goat, as opposed to a khusi, neutered male goal) that cries all night will be a bohka that is quickly cutnu-ed (cut) and eaten the next morning.

Filling up the unkara's (silver jugs) with water before bed is both good for the gods and helpful in having easy access to water to make morning chia (tea).

You can toilet train a baby to pee by (softly) shaking them over a bush and saying "sssssss sssssss ssssss.”

You can put most types of pot on the fire and prevent them from getting burnt if you first coat the bottom/sides of it with a mix of ash and water on it.

Curling all your fingers into your palm except your pointer finger and thumb, and flicking them up to indicate -- where are you going?)

The Nepali head bobble and pointing with my chin.

Running along the balance-beam-wide ledges of rice paddies without falling in (most of the time).

If you can't get through the border at one check point, go to the next one while your school committee goes through another.

How to plow with oxen.

How to boil and filter water buffalo milk.

Terai ants will get into your peanut butter even submerged in a bucket of water with a brick on top. They will sacrifice themselves to become a bridge for the others.

How to eat ants that found their way into your peanut butter.

How to bounce down a mountain without hurting your knees, feet or ankles to avoid Sahib’s knee (the Sherpa shuffle).

Not to use too much battery acid to cure/tan a rabbit pelt.

Ants attack my food even on my kerosene stove.

Hiring a rickshaw and having the driver sit in the back with your friends so you can pedal home, cause it looks like fun and somehow feels right.

Opening flimsy padlocks without a key by batting them around.

There's no line here! Elbows out and go for an opening!

If the river water is deep and current strong, you can cross as a chorus line, arms around each others' waists.

0 notes