Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

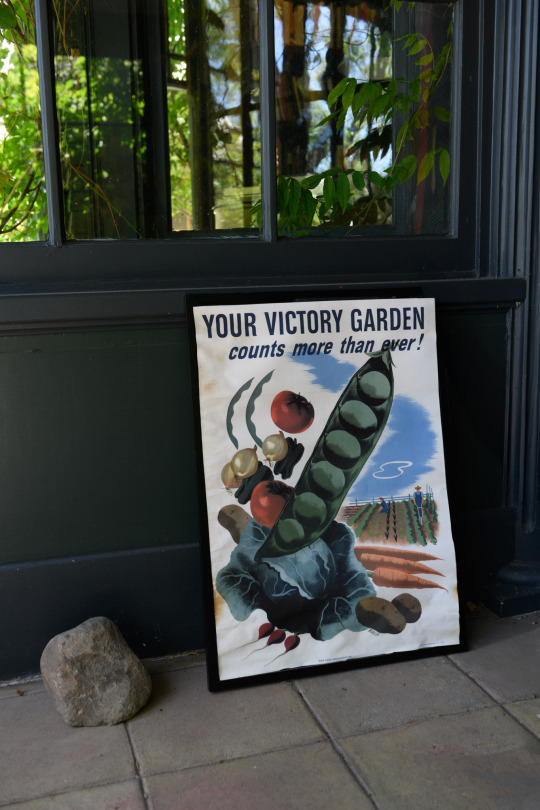

Caterina Fake: Northern California Legacy Spotlight

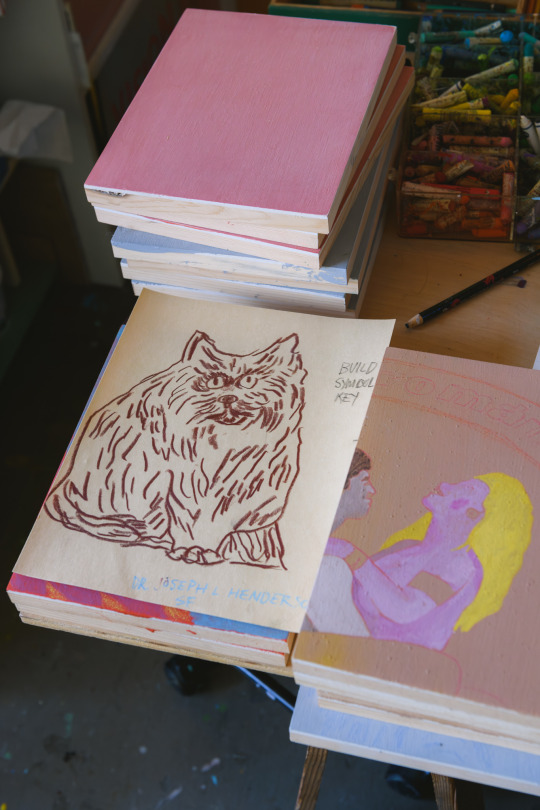

This month we interviewed Caterina Fake, who lives between San Francisco, where we took these photographs, and New York City, where our long-time collaborator Walter Ancarrow did this interview among stacks of books and paintings and voileipä, which is the Finnish word for sandwich and a delicious way to make them (instead of mayonnaise, use butter). Both of Caterina’s homes are conversation-pieces in that both are like having a conversation with Caterina: full of contrasts and curiosities and distractions that go every which way except where you expect.

Caterina is an entrepreneur, an artist, the heart and mind behind Flickr, which she co-founded, and an early investor in Etsy and Kickstarter, among others. She now hosts salons and works on her own art, with an upcoming show at the Jones Institute this October. Prior to this interview, we thought these two lives of hers—technologic, artistic—were another pair of her contrasting pieces. But as we learned, for Caterina both are ways of telling stories, the oldest technology we have of bringing people together. This interview has been edited for clarity and the linear constraints of prose. You just had to be there. Walter Ancarrow: The first time I met you [here in New York] everything was in boxes because you had just moved in. Then I saw you again three weeks later when I came for the salon, and it looked like this, like your San Francisco home, as if you had lived here forever. Caterina Fake: Right? Most people come in here and are like, oh, how long have you lived here? Assuming that my answer will be like 10, 15 years. The other thing that's really peculiar about this place, from my vantage point, is that the walls are all white. I don’t own this place, so there’s white walls. But in the entire San Francisco house, there's no white walls. WA: What color would you paint them if you could? CF: Setting Plaster, which is this pink color, a Farrow & Ball pink color, which I love and am kind of obsessed with. Then the kitchen would be another Farrow & Ball color called Breakfast Room Green. I have also grown to love the color of the bedroom upstairs, which is painted in what I think is Benjamin Moore’s Witching Hour, and it's amazing. WA: I love the color names. There’s a Roland Barthes quote: “Do not all the colors in Nature come from the painters?” CF: Yes, like the Biblical naming of the animals. The naming of the animals as being the first creative act. WA: What's going on in your mind when you're decorating these homes? CF: There's no thought to it, it's just accumulation. In front of us is an American colonial lathe-turned leg table, a Blanc de Chine piece of four bathing beauties, a Tibetan thangka of Avalokiteshvara, and then above it a Victorian mourning portrait decorated in shells, very beautiful. None of these things are from the same era, the same country. But somehow it coheres. It’s intuitive. Or over there, the juxtaposition of this guanyin statue with a painting of Matthew Henson, the first Black man to go to the North Pole. The two of them make this lovely couple. They would never appear together in any other place other than this house.

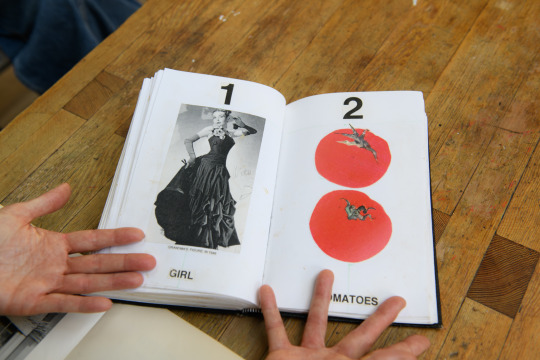

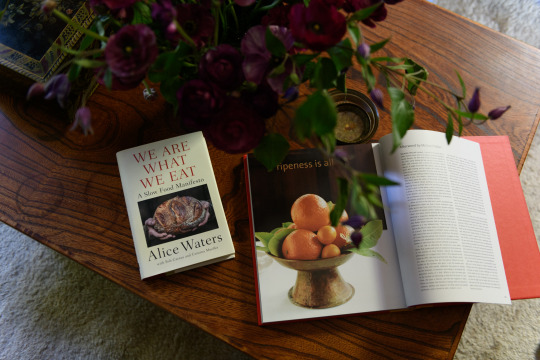

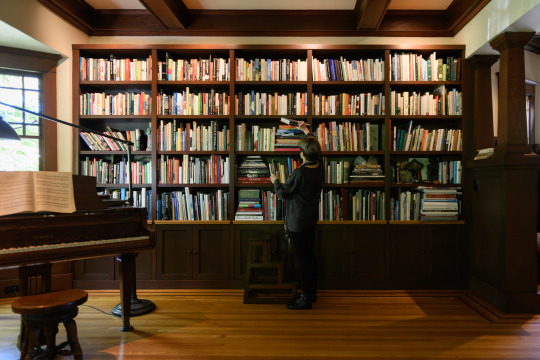

It's trial and error. I don’t have any bookshelves. Everything gets stacked on the floor in random order. WA: How about I pick a book and you give me one word that comes to mind. The Journals of Thoreau. CF: [A lengthy monologue on Thoreau as technophile, his obsession with telegraph poles, his likening of their hum to “music of the spheres,” technology-as-magic, the OED as one of the great masterpieces of Western culture, then the reading of a long passage from his journal] WA: Everything you just said, can you summarize in one word? CF: [Laughs] Re-enchantment.

WA: Okay, what about this book, George Saunders’ A Swim in the Pond in the Rain. One word. CF: ThisbookissomethingthatIgivepeoplewhoareinterestedinlearningabouthowtoreadliteratureanddon'treallyknowwheretostartit'samazingwhathedoesishetakesalloftheseshortstoriesbyChekhovandTurgenevandalloftheseotherRussianwriterswhoIalwaysfoundalittleshallIsayturgidandthenhetalksaboutthemscenebysceneit’sbrilliant. WA: Blood Meridian.

CF: Violent. WA: Oh, I just bought this book [Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations]. There is a quote in it that I love, he’s actually quoting someone else: The nomads are the ones who never moved on. CF: The nomads are the ones who never moved on. They just continue. Wandering. The rest of us have settled. WA: It's so true to life right now. Don’t you have a show coming up in San Francisco? CF: At the Jones Institute. I am bringing a 19th-century opium bed into the curator's home where various friends and artists will be invited to come and dream. They will actually come and stay and sleep in the bed and record their dreams if they have any. If they don't have any, I'm going to fill the room with dream creatures and dream objects and create what the Jungians would call a sand table to create an impressionistic kind of story you collect from all the dream objects. WA: What constitutes a dream object? CF: Anything that has some kind of evocation. For example, this [a wooden carving, one foot long, of a Victorian woman in a vest wearing a bowtie; she has no arms and no head] is kind of a dream object. The Surrealists nailed this. "The chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table." WA: It makes sense and doesn’t at the same time. It goes back to how you arrange items in your home, these wonderful, accidental contrasts. CF: They’re evocative, they tell a story. It’s kind of like a story cabinet. I have a story cabinet [in San Francisco] full of tiny little figurines. Some of them are from nativity scenes. Some of them are mechanical cars, toys, junk that you find in a rummage sale, sculptures, a lighthouse, a car, a tiger, a devil, an angel, and so on. The story cabinet has all these little objects in it. And then the whole house—somebody said you don't need a story cabinet, the entire house is a story cabinet, a cabinet of curiosities.

WA: The Jones Institute is out of Aida Jones's house. That seems like a better place to be dreaming. CF: I really wanted it to be in a house. I'm not a big fan of the blank slate or white contemporary box feeling of most gallery spaces. One of the best exhibits I've ever seen was at the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice. Mariano Fortuny was famous for his textiles and his family turned his palazzo into an art gallery. It was one of the most stunning shows I've seen because it had couches and sofas and the walls were covered with the Fortuny fabrics. I always thought it would be the perfect gallery space. WA: You host salons here at your house. How did that begin? CF: I’ve always organized things like this. I had a thing called Mythology Club where you bring a myth to tell, or a story that has been rubbed smooth by multiple retellings, or a song. You could tell a story from your family that has been told so many times nobody knows if it's true anymore. It's become fable. WA: [Smiles, daydreams] CF: I had a critical theory group which went on for many years with my friend Eric Rodenbeck, who lives in Inverness and is now an ink maker and designer, and we were reading things like Adorno and Horkheimer. WA: Have you always been like this, artistic, bringing people together? I remember your mentioning once wanting to move away from your earlier years in technology. CF: I was always planning on doing things in technology that were humanizing. The things that I’ve worked on like Flickr and Etsy and Kickstarter have to do with being platforms for people’s creative work. That part of the internet has been largely lost, but a lot of the technologies of AI are built on top of the stuff that we were building in that era. You asked about the origins of the salon. We used to do what we called photo forays on Flickr where people would go out together to an interesting place and take photos, a group activity. It’s community building, it’s putting people together, introducing people to each other. I've always done that. It’s what I felt the internet was best at. Granted, you can form really bad communities. You can form communities of white supremacists or cannibals. People who are without conscience or moral compass can abuse that capacity. That was the great tragedy of the internet. WA: When was the internet’s golden age? CF: It ended in 2007/2008 when Facebook reordered its feed. Instead of being reverse chronological, most recent at the top and going backwards in time, it was ordered by what got the most attention. WA: The algorithm. There’s something about the chronological aspect as what we've lost that really strikes me. It's hard to articulate... CF: It’s time, it’s the passing of time, but not in the sense of clockwork. Time can be conceived of as technological, the manufacturing of time, because humans created time. WA: But you're talking about a different sort of time. CF: Exactly. I'm talking about the sun rises, the sun sets. Time expands and contracts. WA: Like being in the presence of others can slow time or make it go faster. CF: Yes, to spend time together, that's a different way of thinking of time. You know how whatever the traveler sees are things that the map maker will never know? There is an experience of being in a place that you can't get from looking at a map. It’s the romantic versus the technocratic viewpoint. That's why I've had this career that I've had, which is peculiar but necessary. I’ve been this romantic in a technocratic world.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#san francisco#interiordesign#caterina fake#caterinafake

1 note

·

View note

Text

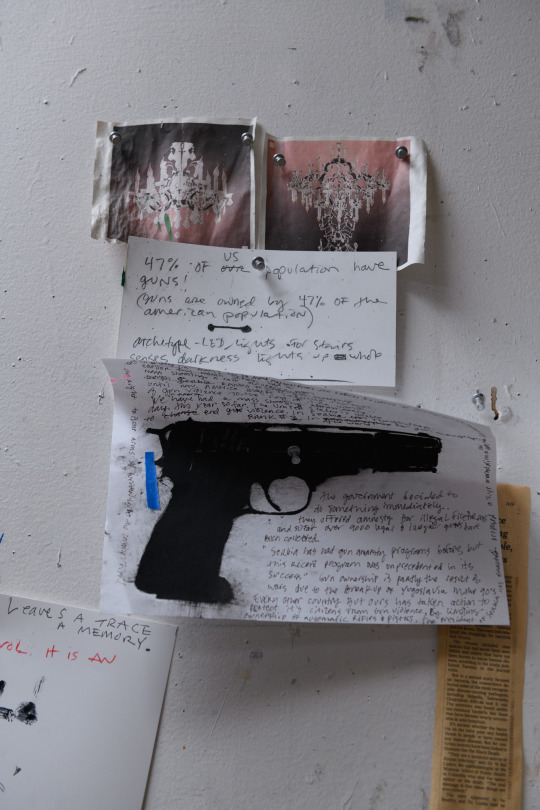

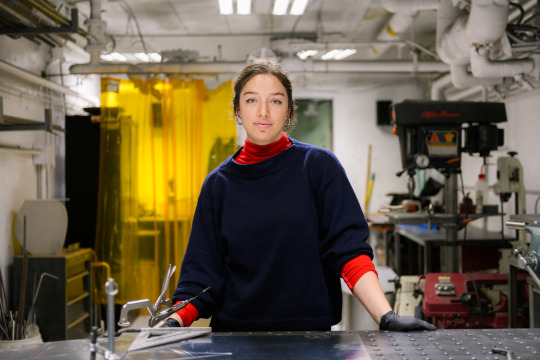

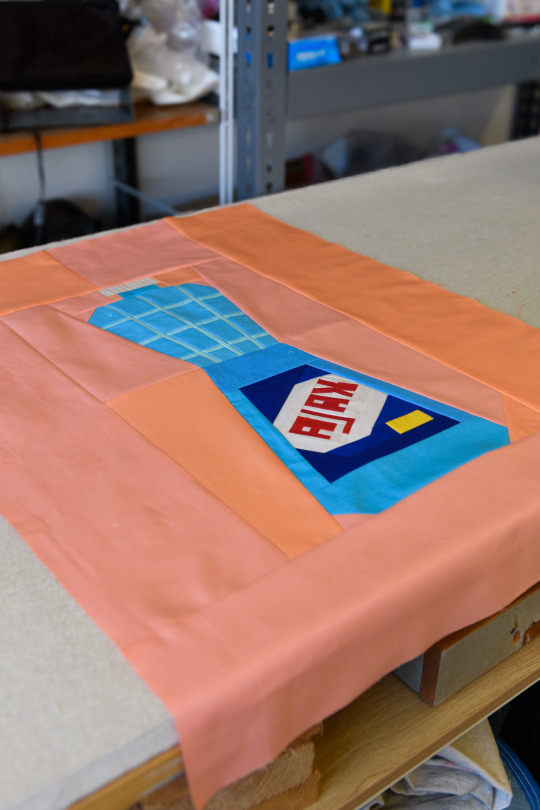

Artist Spotlight: Nico Corona

We hope our summer is just like this Nico Corona interview: all fire, warmth, gay shit, and chains, the chains we wear, the chains we break out of, the chains that are a metaphor for the links we form between each other. Also thank you Nico for "BDSM hacker bitch techno" which we believe is this year's Brat Summer, and for the amazing curated list of places to check out in the city, which you will find at the end of this interview.

Studio AHEAD: Tell us about the piece you are showing next month for our exhibition at Superhouse June 19th to August 2nd in New York. Why did you choose a chandelier? How does this piece fit in with where you are now, creative-wise?

Nico Corona: Ooo yes, I’m excited about this show, such an honor. So we were prompted to make a piece of work based on architectural elements. I didn’t even know what that meant [laughs] so I did some research, asked some friends what this meant to them. I knew I wanted to do something in the lighting category but didn’t wanna fuck around with anything electrical, and I’ve done some candelabras with chain, so I thought it would be cool do a megazord candelabra chandelier. I love primordial elements. I am a fire sign so I thought of course I’ll do a non-electrical, lighting sculptural rendition. I love the idea of unplugging and doing something intimate, forming the chains into a circle to prompt an intimate space

To gather around and socialize, the rings of fire can hopefully bring people together, hopefully off of their phones.

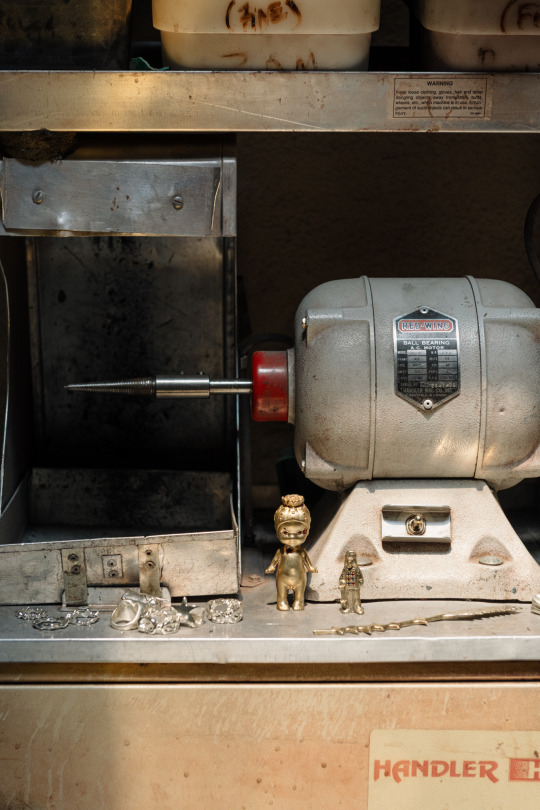

Studio AHEAD: Give us a bit about how you started working with metals?

Corona: I started working with metal out of curiosity. It was a bit later in life I had a realization that I had the confidence to make sculpture work. Metal is very durable and has a long life, I feel like it’s an archival material, so after when I’m dead I’ll leave behind a bunch of metal objects. You would really have to put an effort in destroying my work.

Studio AHEAD: What is the metal smithing scene like in San Francisco/Oakland?

Corona: I’m not sure if there really is a metal smithing scene in SF/OAK. From my perspective I feel like that term is a bit antiquated, but I do think there is a big interest and wave of artist interested in metal as material to work with. There are a handful of studios in the Bay and some DIY places too. The thing about the Bay is there’s always an undercurrent of people doing things on a DIY tip, whether it’s knowledge sharing, workshops, or resource gathering—probably because of it being such extreme place in the sense of wealth and disparity.

Studio AHEAD: You wear a lot of jewelry and seeing you wear so many pieces at once, there is an obvious masculine/feminine, hard/soft dichotomy going on. Are various cultural influences at play?

Corona: I actually don’t wear a lot of jewelry: at most I’ll wear two rings and a vintage ball-and-chain necklace. Two silver earrings made from scrap metal. I’m trying to shift away from masculine and feminine dichotomy. But I’ll often work in opposites. I’ll make a set of things that feel sharp, angular, and fixed—I’ll study that and make something that is the opposite stuff that is fluid, moving, and rounded. I’ll make something super tiny and then make the same thing but scaled up.

Cultural things at play—yes! There’s an undertone of my cultural background in my work. I’m Bolivian and Mexican, I come from an immigrant background, so being resourceful, a clever use of materials, and building things to help improve a person’s life. I inherited this directly from my dad, it’s a part of our culture (and a lot of other cultures). To just make things work with what we got, it’s a very beautiful thing. Also popular culture influences me, the animated world, music, and gay shit. So yeah very serious cultural undertones that engrained in me and popular culture stuff that isn’t very serious, that’s playful.

Studio AHEAD: The chains seem to build upon this. Chains are confining, fetishistic, protective... Can you elaborate? You use them a lot.

Corona: Chains are an everyday object but are referenced so much all throughout history. This is why I love them as a symbol and a material to build. They have been used as a literal symbol or object to keep you from freedom. They can constrict you, they can liberate you, and they can also be used to make chairs [laughs]. Again pretty serious associations and truths with this material. Yes, they’re referenced in fetish culture, they’re sexy, but also very practical. I love seeing people wear chains as jewelry and they attach little charms to them, people hooking charms to their chains, you can see a fragmented identity with what they attach to their chains. A concept I’m super drawn to with the chains is how a singular link is not as powerful as a series of connected links. I really love this. It’s a reminder that we should always stay connected and a metaphor for humanity.

Studio AHEAD: The earmuffs that you wear to protect your hearing while metalworking look like headphones. What music have you been listening to?

Corona: Oh! I think I had a past life in the 80s. A lot of stuff from the 80s: new wave and Madonna. Rock en espanol, cumbia. A lot of stuff my parents would play when we would clean the house that I resented I am super in love with. Music that reminds me of family and my childhood. I love 90s rap and R&B. Jazz, Sade, and BDSM hacker bitch techno.

Studio AHEAD: I love BDSM hacker bitch techno. What’ve you been enjoying lately in the city?

Corona: Book shopping at Et al. Books in the Mission. It’s close to my studio. Of course going to Auto Erotica in the Castro, I’ll bug the store owner Patrick. Adding to my collection for my archive of illustrative xxx work. Shopping at Body Philosophy Club, Twotwo in Oakland, and Shop Relove. Record shopping at Dark Entries in the Tenderloin (they also have great vintage gay ephemera). Listening to mixes from local DJs, Lowergrand Radio / Unity Press. Eating Ethiopian food at Club Waziema, one of the only Black women owned bars in SF! Probably the most important places in SF’s history.

Walking from Land’s End to Ocean Beach.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#interiordesign#oakland#Nico Coronoa#Nicocorona

0 notes

Text

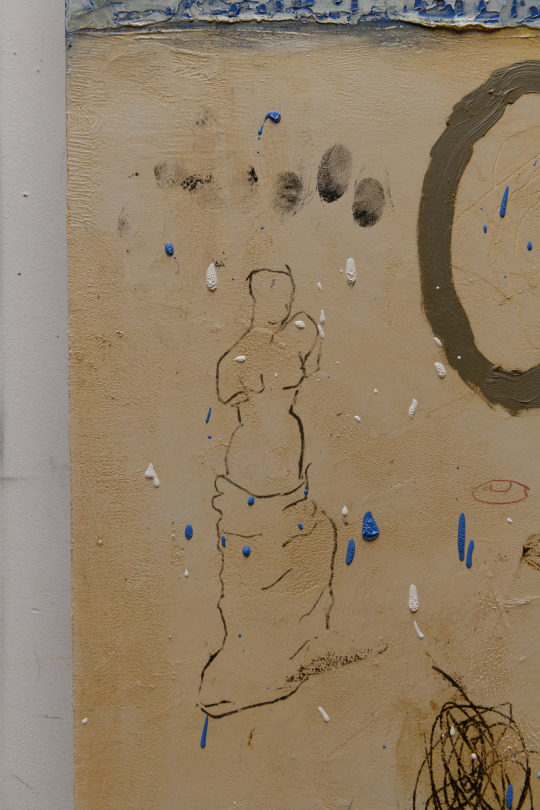

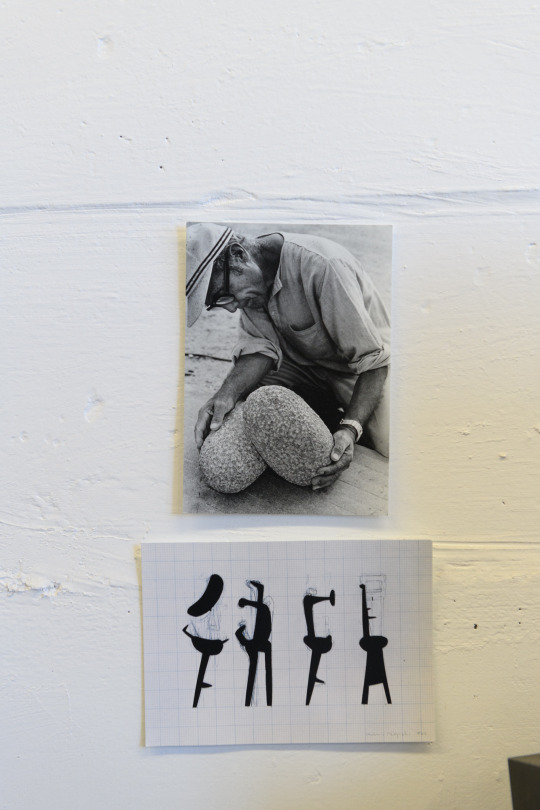

Artist Spotlight: Gay Outlaw

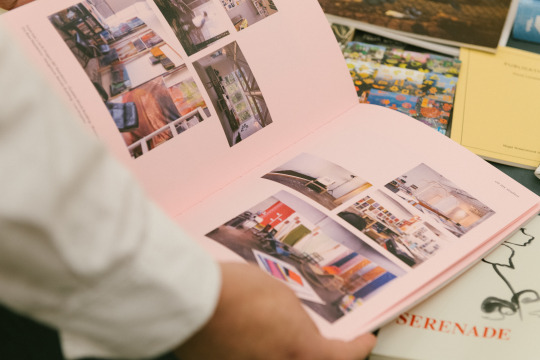

Perhaps the title given to her JSMA exhibition, “Mutable Object,” is the best description of Gay Outlaw’s work: sculptures and prints that seem pure explorations of form and color, going wherever the imagination leads. The treasures found during these adventures of the mind were everywhere on display in her Outer Richmond studio when we visited last month, where, like a page out of Euclid, the shapes of the universe are pared down to their essentials so that they can be built up again in new and surprising ways. Although Outlaw prefers the shapes to speak for themselves, she had no problem telling us what each evokes—“Ellipses are so beautiful and they feel like they are slipping around”—how to stay creative throughout a long career, and why she uses puff pastry as a medium.

Studio AHEAD: Tell us about the piece you are showing at Superhouse in NYC in June. It is based on an earlier piece, “Puff Supports,” made out of pastry.

Gay Outlaw: The piece for Superhouse is a reprise of a piece I made first in 1996. I made it again for a show in Los Angeles in 2010. This will be its third iteration. It’s a temporary, site-specific work, so it has to be remade, or rebaked, for every exhibition.

Just after moving to San Francisco, I experienced the Loma Prieta earthquake and the memory of it really stayed with me. I grew up on the Gulf Coast with hurricanes, which we could obviously see coming well ahead of landfall. It was the unexpected nature of the earthquake that really threw me—the fact that the architecture all around us, which one minute seemed completely stable, could liquify in what seemed like an instant of shaking. Thus the title “Puff Supports.” I could never look at solid walls the same way again.

Studio AHEAD: Can viewers eat it?

Outlaw: It is not intended for consumption, except maybe by mice…?

Studio AHEAD: You studied at the École de Cuisine la Varenne in Paris. Was it there you decided to become an artist? Besides the obvious connection between your use of perishable materials and the École de Cuisine, I’m curious what made you transition from culinary school to arts.

Outlaw: I think I decided to be an artist when I was a little kid. I kept it to myself for a long time, and even tried to repress the urge when it seemed an impractical choice for so many reasons. My father wanted me to go to law school. But art eventually won out.

There was really no transition from cooking school to art making. I think of it all as part of the same path. I just went to cooking school instead of art school. I couldn’t see myself working in a kitchen afterward—I am not that physically strong. I had a string of jobs in food sales and marketing and did a little cooking, and while I was doing that I started making photographs. Which eventually led me to want to make sculpture.

Studio AHEAD: What shape is really speaking to you right now?

Outlaw: At the moment I am studying paper pleating, and thinking of ways to transfer that geometry and energy to other materials… see what shapes present themselves in the process. I see pleating everywhere now, and I can see that it has qualities that have caught my eye before. Vibration. Rhythm. Triangles, which I view as feminine and stable forms.

Studio AHEAD: What about circles, squares, rhombuses…

Outlaw: I’ve always thought of circles as symbols of the self, of a fixed set of qualities or experiences. I love Venn diagrams as a way of presenting a situation.

But I work more often with ellipses. Ellipses are so beautiful and they feel like they are slipping around—more dynamic than circles. I designed a perforated cube when my kids were little and it’s a very specific thing. The perforations come through the faces of the cube and make elliptical openings. I have photographed them and incorporated them into my sculptures for years.

The other shape that I often return to is the hexagon. I learned from bees and wasps that hexagons pack very efficiently into a very stable form. Fun fact: an isometric drawing of a cube yields a hexagon which I think is very cool.

Studio AHEAD: A lot of your work seems to be built around exploration of material and form. At the end of this exploration, what do you hope to find? How do you know when you’ve gotten to that place?

Outlaw: I have found the key to making art for a lifetime is to work with a really open, present mind. I don’t ask myself whether what I am fiddling around with will lead me to a certain place. I just go with the flow of my hands and brain. I finish a piece when I have no more time, or when it stops making demands of me.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#interiordesign#gayoutlaw#gay outlaw

0 notes

Text

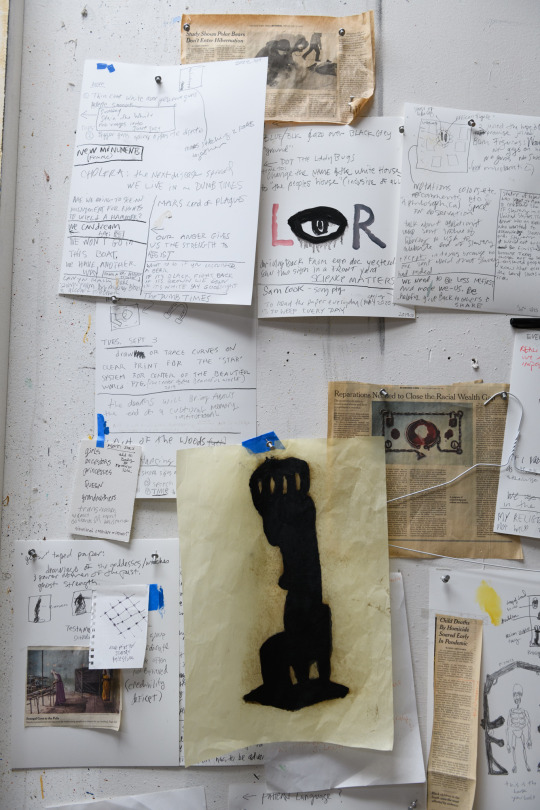

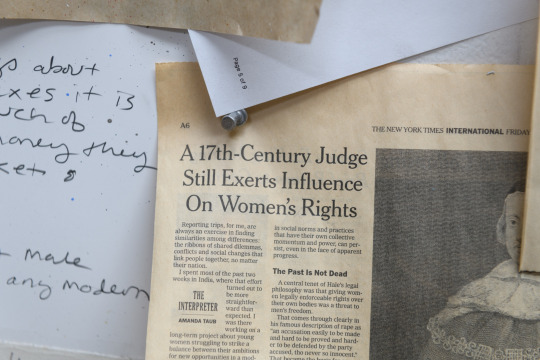

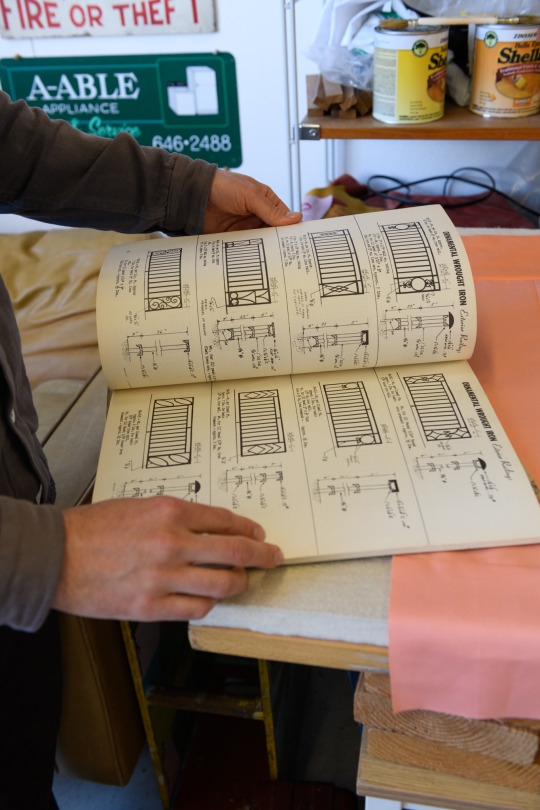

Artist Spotlight: Ben Peterson

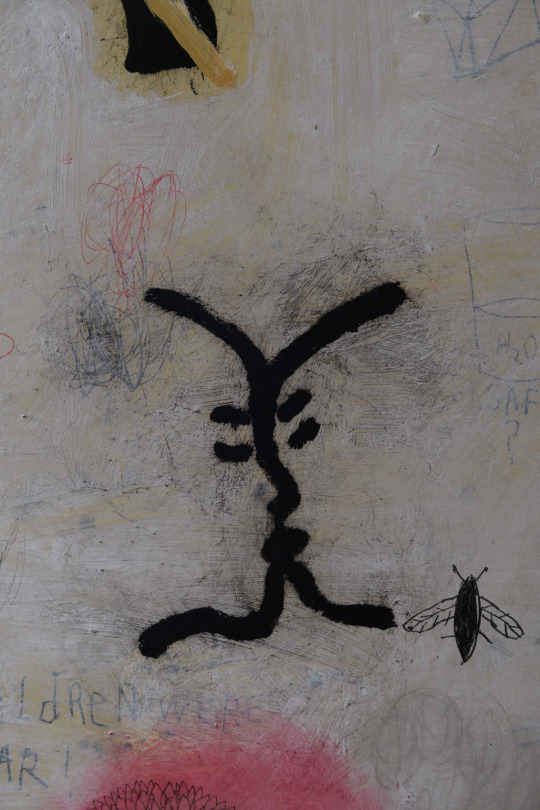

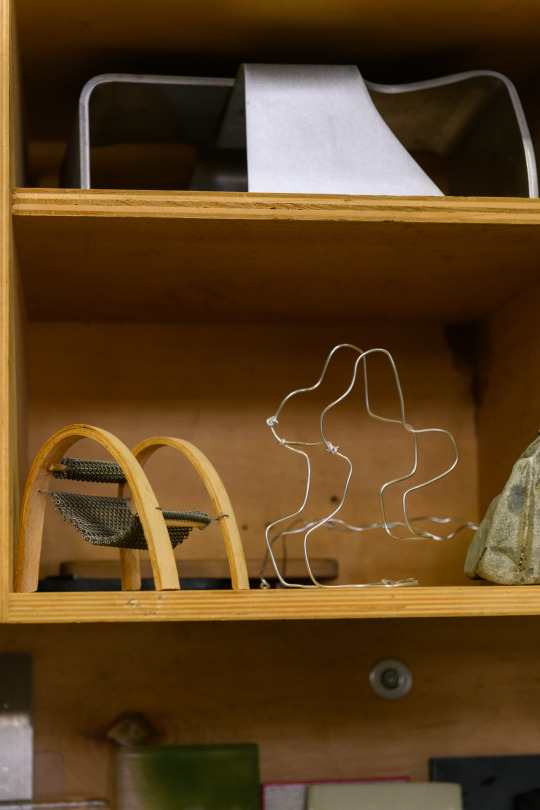

Ben Peterson is an Oakland-based artist working mostly in clay. A few weeks ago we visited his studio, where among spare modernist furniture were Ben's own creations: vaguely familiar, seemingly functional sculptures with no function. Except for their clean lines and perfect form, they might be something found during an archeological dig, but the civilization to use them has either not yet been created or was lost to time. Ben himself is down to earth. On a shelf were small sculptures somewhat resembling animals, or more accurately, glyphs of animals always pointing to something they are not.

Studio AHEAD: Your Instagram is @newertopographics. Are you furthering the pivotal New Topographic exhibition of 1975?

Peterson: I wouldn't say furthering... that show, in particular the photos and the aesthetic associated with it, were a critical early influence on my work and in some ways they continue to be. That show and photographers like Lewis Baltz and John Divola helped to open my eyes to the built environment and also gave me a way to articulate my own approach to landscape and objects. Also I love the way topographics can be confused with typography as a lot of my early art experiences involved writing on things without asking.

Studio AHEAD: I can see the typographic influence—almost like the Mayan writing system. Many of your works also have an industrial detritus look to them (in the best way). Is this from spending a good bit of your life in Oakland?

Peterson: I think the answer to this question really follows the first, in that I grew up in central Nevada in a small rural community that is also the world’s largest military ammunition depot. It’s surrounded by hundreds of cement bunkers. I also grew up mining with my family and living most of the summer in a cabin built in the late 1800s. There were a number of ghost towns and abandoned mining structures nearby. I moved to Oakland (San Francisco first) when I graduated high school and spent my first few years in the Bay Area skateboarding and playing around in derelict buildings, so I'd like to think I came by my interest in the industrial, the fragment and ruin, honestly.

Studio AHEAD: You recently returned here after spending some years in Houston. What did you miss?

Peterson: If I’m being honest, I pretty much missed everything [laughs], but what really cemented our move back was the realization that I had spent so much of my life here in Oakland that it was hard to articulate what I was trying to accomplish with my work and why or who my peers were or my influences. While living in Oakland I didn't give it much thought, but in Texas I was teaching at the University of Houston, and most of my students were pretty unfamiliar with art history, let alone Bay Area art history, so I really had to build a context/history for myself as well as tell my version of the history of art in the Bay Area. You could check out my friend Jamie Sterling Pitt and his Instagram mariposa_south_west where we tried to put together some of our shared influences, many of whom were firmly rooted in the Bay.

Studio AHEAD: Describe to me a perfect day creating something in your studio.

Peterson: I would get started working around 8am post-coffee. I enjoy the finishing portion of my work the most maybe (it’s where the surprises and spontaneity are), so I would be either putting the final surface treatments on greenware or plastering a fired piece. I don't glaze. Music usually starts mellow and gradually grows more intense... think Townes van Zant (“At My Window,” the Be Here to Love Me version). I listen to a lot of sad country / folk, mostly pre ’77. Lunch is probably a bean and cheese burrito. I usually make a big pot on Sunday, I love to cook. The afternoon music would probably be post-punk pushing into electronic music; I love subwoofers. Sometimes I get in the mood for an end of day harsh noise track or two [laughs]. Although it's a total fantasy, ideally my friend Carlos Matos would drop by and we could go get a drink and talk architecture.

Studio AHEAD: In June you are presenting, with Gay Outlaw and Nico Corona, some pieces at Superhouse in New York. Tell us about the piece and your process in making it.

Peterson: For the Superhouse show I'm making a fireplace mantel. The idea was in place before the fires in LA, but after of course... I’m still a bit nervous about writing down where I am with my thinking. Being born and raised in the rural High Desert I have a relationship to nature and my environment that I have come to understand is very different from people raised in green, lush environments. I’m thinking a lot about Wallace Stegner, the Army Corps of Engineers, a book called Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins, and Gaston Bachelard’s The Psychoanalysis of Fire. Ceramics are of course born in fire.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#interiordesign#oakland#ben peterson#benpeterson

1 note

·

View note

Text

Artist Spotlight: Daria Halprin and Ruthanna Hopper

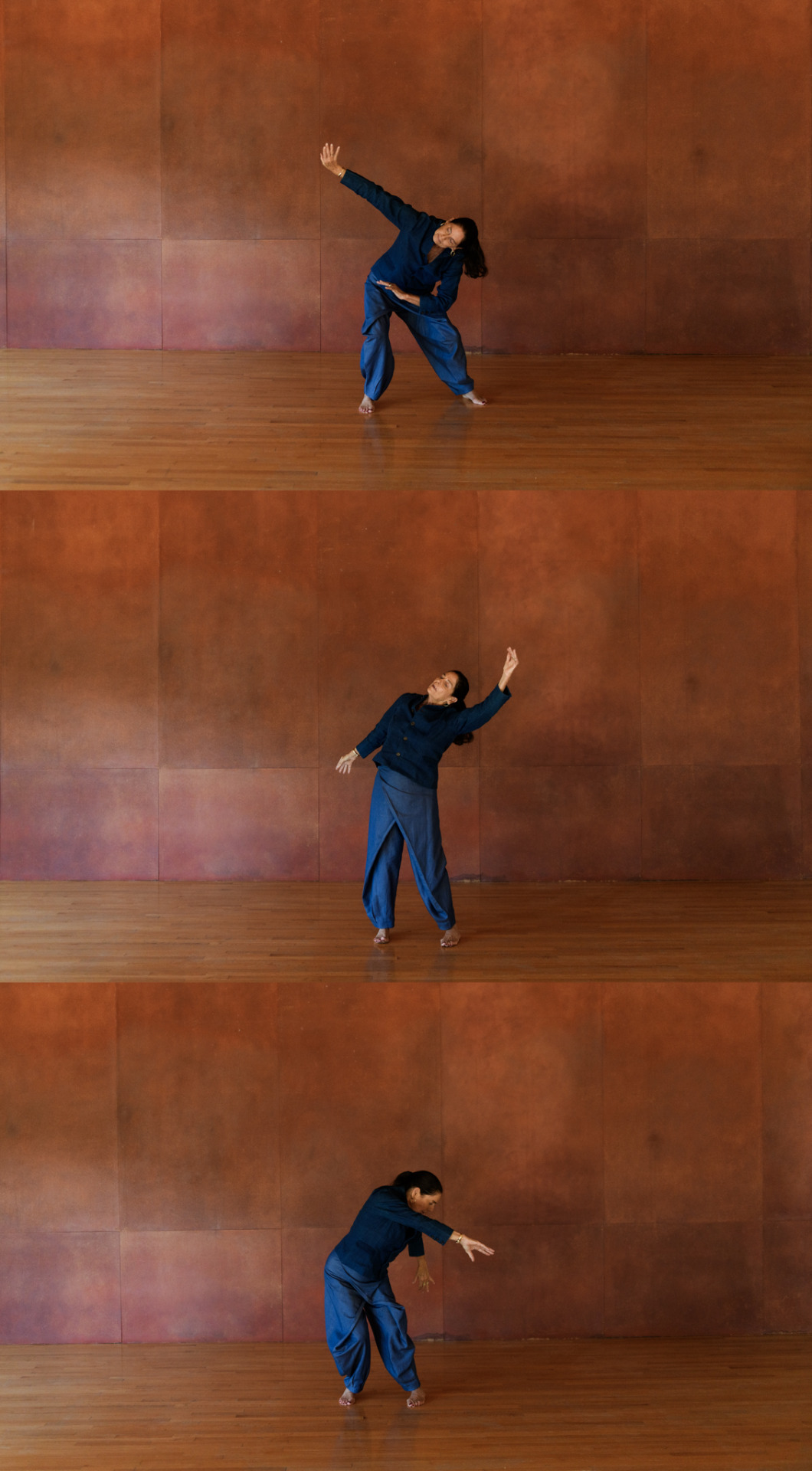

The term “movers and shakers” refers to anyone who has an outsize impact on their field. For Daria Halprin and her daughter, Ruthanna Hopper, the term is as literal as it is figurative. Daria is a dancer, instructor, and somatic movement therapist, and daughter of famed choreographer and dancer Anna Halprin. Ruthanna is a visual artist whose paintings have the expressive, kinetic quality of dance.

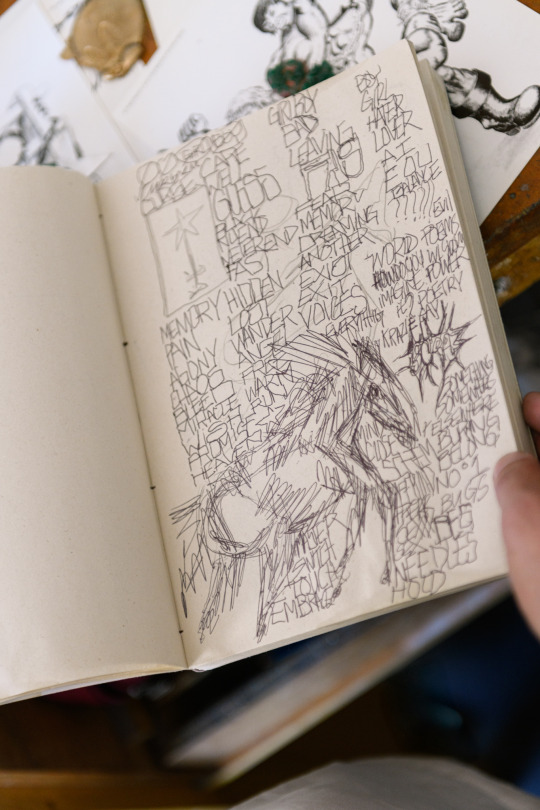

In 1978, Daria and Anna founded the Tamalpa Institute to teach movement- and art-based therapy, going on to teach thousands of students from their studio in the hills of Marin. We visited earlier this year, where Daria showed us some impromptu body movements and Ruthanna some sketches she’d been working on.

Studio AHEAD: We have to start with the dance deck and the Mountain Home Studio in general. It seems to be an extension of, rather than an intruding into, the Marin landscape.

Daria Halprin: The dance deck was designed by my father, Lawrence Halprin, with scenic designer and theater teacher Arch Lauterer.

The residential house was built first. The studio and dance deck were built in 1953/54. The idea was to create a space for my mother, so that she could create new works in a new kind of dance space and be “at home.” The deck was envisioned as an outdoor studio, cantilevered off the slope that leads down from the residence to the studio. Its shape was designed to integrate with the surroundings—the sloping of the land, the redwood forest and Madrone trees, and to capture as much natural light as possible.

Benches were constructed on the hill going down to the deck to serve as observation seats, like an outdoor theater, challenging the notion of the proscenium arch as a boundary between performer and audience.

The studio sits at one edge of the dance deck and the untamed forest on the other side. The studio ceilings are quite high and there are floor-to-ceiling glass sliding doors and windows on all three sides. The ochre walls of the studio provide a dramatic background that highlights us as we occupy the space.

The dance deck and studio invite both mover and witness to move in between indoor/outdoor environment and became part of the natural landscape. The wooden walkway from studio to dance deck ritualizes the transition.

Artists and students studying the Halprin work have infused the space and been infused by it. The artifacts and resonances of so many remarkable people and passionate students live in the place. Over the decades it has become a refuge and spiritual home for artistic practice, study, and performance.

Studio AHEAD: Ruthanna, your ongoing Passages is also site-specific. What makes it so? How are you engaging with the space as already there?

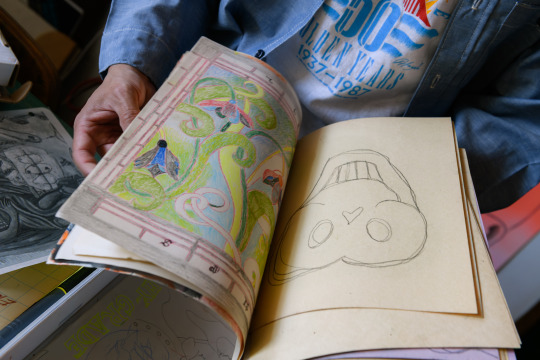

Ruthanna Hopper: The Passages installation and on-going project is a conversation through creative process with my grandfather Lawrence, connecting with his design work. I was incredibly close with my grandfather and we spent a great deal of time together in my growing-up years. He took me on long walks from the back door of the house to Phoenix Lake through the redwoods and over fern paths where my grandfather taught me never to pick a wild flower where she grows. He had a prolific drawing practice and he gave me my first sketchbook. On our hikes, we would sit together on mossy rocks and make drawings. We had wonderful conversations where he would make me feel like he cared about my take on things. As I grew up, I began to understand what a gift it was as a young girl to feel heard and seen.

My grandfather created a scoring system for creative response called the RSVP Cycles, which is a method that is a resource for artists and designers and communities to create a process in collective creativity and design thinking. The Passages project comes out of a score that I created utilizing his method and in its first iteration is an installation at Levi’s Plaza, which he designed. I see it as a re-generation project, connecting to his landscape designs, in homage to him and in our shared love language of art making.

The Passages project is a way for us to continue our conversations.

Studio AHEAD: Daria, you have also spoken about your childhood hikes with Lawrence. After all these years, what has stayed with you about those hikes? What still guides your practice?

Daria: We hiked from the time I was six years old, going into the High Sierras and camping out for two weeks every summer. First and foremost are the incredible memories of times spent with my father, the inheritance of a deep embodied love for wild nature, a sense of physical presence and strength in my body, and a wide-open imagination. Our home had a quality of wild nature as well. In some ways nature felt like a second home to me.

Studio AHEAD: Can you describe the moment when you know you've truly expressed some inner part of yourself through movement/dance? It is a feeling suddenly attained? A flood of emotion? How do you know you've gotten there?

Daria: That’s quite a big question. I have spent years exploring and articulating maps that would guide people toward those kinds of experiences. There are principles, maps and methods that help us “get there.” For me the moment is an experience of complete connection between body and mind: a flow and dialogue between my body moving, my mind imagining, my feelings expressing.

I experience movement as a language, it speaks to me as much as it speaks for me. In those moments of total attunement, I experience my body as an instrument, I become the instrument, I am playing it and listening to its voice.

Ruthanna: I think this is what artists are grappling with, and non-artists as well, the question of “how do I truly express myself”—how do I get to a place of congruence where the inner picture meets the outer picture? Going into the studio is facing yourself and saying I commit to contending with my interpretations and to myself and how I’m going to transmute those influences into some kind of coherence, some kind of integration. There’s a fleeting moment of feeling complete in a painting and then coming back to it and feeling the opposite, like nothing’s working and so beginning again and again, which is the way it goes in life and art. So those moments of feeling something is attained, feel fleeting and impermanent.

We often have an easier time recognize that creative attainment in others, when we’re moved by art and artists, musicians, dancers—we can see and feel deeply when they’ve had the fulfillment of a full inner expression, because that energy they’re transmitting gets shared with us and it feels like an incredible honor to witness that, like we’ve been privy to magic and the particles shift in the space. This is why art and artists are so important—when there’s an experience of creative authenticity we are moved to understanding and seeing some part of ourselves in its reflection.

Studio AHEAD: What are, so to speak, your next movements?

Daria: On some days I have a clear sense of what my next movement wants to be and on some days I really have no idea. I think about how I want to spend my time with my grandchildren, taking walks in the gorgeous nature where I live, I want to keep teaching. At my age I am feeling my next movement is circular where it used to feel like an extending line.

Ruthanna: My next movements are a daily question, especially during these times. I will continue to show up for art and artists, to make art and to support others in making art. I’ll keep looking for ways to connect to the environment, to Passages, my own and others, and to pick up the extending line my mother speaks of, to carry-on connecting to the Halprin lineage work, coming back to my roots and to the redwood grove and Mountain Home Studio, a full-circle…

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#interiordesign#oakland#marin county#marincounty#anna halprin#lawrence halprin#ruthanna hopper#daria halprin#Tamalpa Institute

1 note

·

View note

Text

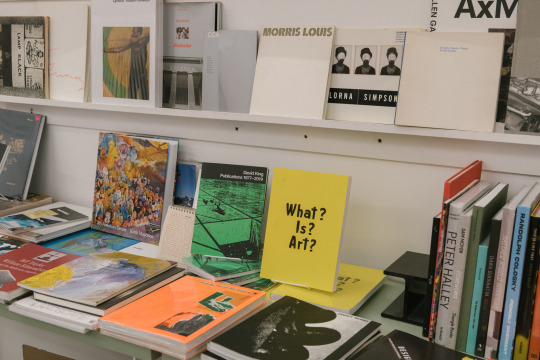

Gallery Spotlight: Et al.

Et al. is Latin for “and others,” shorthand for some of the most interesting works currently being displayed in the city (as well as being a fantastic bookstore), and is a great community-building project in whatever universal language we’re all speaking. Et al. is also Jackie Im and Aaron Harbour, who started the gallery in 2013 with Facundo Argañaraz back when it was in the basement of Union Cleaners. Now it is in the Mission and currently hosting the second iteration of Same Blue as the Sky. It’s been a busy time for all of us, so we were happy Im and Harbour could find a little bit of time to talk with us.

Studio AHEAD: We’re really excited and honored to be holding Same Blue as the Sky at your new location in the Mission. What’s the history of Et al. finding space in SF?

Im and Harbour: Et al. has always found our spaces through good fortune and help from many in our community. Our initial curatorial work took place at MacArthur B Arthur in Oakland, a space founded by our friend, the dearly missed Kevin Clarke. It was through a post on social media that prompted us to start organizing exhibitions there. After MacArthur B Arthur closed, we partnered with Facundo Argañaraz (now of 1599fdt) to found Et al., and he found our Chinatown space while walking past Union Cleaners and seeing a sign in their window. We were able to have a space in the initial years of Minnesota Street Project, through a very generous invitation. And eventually we ended up in the Mission by asking (or maybe more realistically bugging) Ratio 3 about the empty storefront next door to them. Our current gallery is in Ratio 3's old one and we are so grateful to have been entrusted with the space.

Studio AHEAD: What’s your history of making space?

Im and Harbour: We are very keen on thinking about what it means to make space or to give over space to others. For us, exhibition-making is first and foremost a chance to give artists room to develop work in a space with as much or as little involvement curatorially from us. We think a lot about hospitality and what we can do to support our community of artists, curators, writers, and thinkers and a lot of that has to do with sharing space. Right now at the gallery, Colpa Press uses a portion of the back room for printing. Our upstairs office hosts Small Press Traffic, a poetry non-profit where Jackie is currently on their board of directors. Our former Mission Street space is now Climate Control, run by Nico Colon. We also will turn our space over to curators of varying experience levels to realize exhibitions or events in the space. Being able to share our space is a vital part of our vision.

Studio AHEAD: Shout out to Small Press Traffic's series of events, especially the upcoming reading from Lyn Hejinian's "My Life" in February. Anyway, the gallery is very much a passion project—you’ve both got day jobs. Is this the reality for gallerists now?

Im and Harbour: The art market as it is now is one that is precarious and at a tough place, especially for galleries of our size. We have both kept working day jobs partly because it enables a certain level of curatorial freedom. At the same time, while it may help alleviate some of the financial burden, it's still a burden on our time and capacity. It was one thing to do this while we were in a basement in Chinatown, only open a couple of days a week, it's another thing altogether to operate a large storefront with a bookstore and a number of folks depending on us. We are working on getting fiscal sponsorship, as keeping the ship afloat has been hefty this past year or two, even with our jobs. For us going forward, we want to find different avenues to stay open and to continue doing the work that we do because most of all we love art and we love the Bay Area.

Studio AHEAD: Not to start drama, but what’s it like working with each other? I mean, I imagine you don’t have the exact same taste.

Im and Harbour: Strangely easy! We have this weird uncanny ability to walk into any large group show and leave identifying the same works as our individual favorites. And while one of us may have stronger opinions on this or that artist (or even book or movie or music!), we tend to generally agree. The other night we were talking about this and we couldn't remember the last time we really disagreed on art, other than Jackie liked Megalopolis more than Aaron, and Aaron liked the second Joker movie more than Jackie did. Haha.

In the more practical sense, Aaron's job is a little looser with his time, so the day-to-day operations of the space are handled mostly by him, while Jackie keeps the space focused.

Studio AHEAD: Can you make a bland, generalizing statement about the art scene here that only locals will know isn’t true?

Im and Harbour: Where there's money, art thrives.

People from outside the Bay have for a long time held the misconception that the presence of so much tech capital implies the scene should be thriving financially when, maybe especially for us, this is far from the case.

Studio AHEAD: God, that’s so true. By the way, happy new year! What are you looking forward to?

Im and Harbour: Right now, we're writing these answers as many of our friends and colleagues are grappling with the devastating fires in Los Angeles. It feels strange to think about what we're looking forward to as so many dear to us have lost so much. We are heartened to see so much of the community coming together to support each other, from near and afar and as we come upon 2025 with a lot of uncertainty and amid disaster, we look forward to the ways in which we can be of support to each other. To hold each other in love and support where perhaps institutions cannot or will not.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#studio ahead#Jackie Im#northern california#bayarea#art#california#san francisco#interiordesign#oakland#gallery spotlight#et al

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

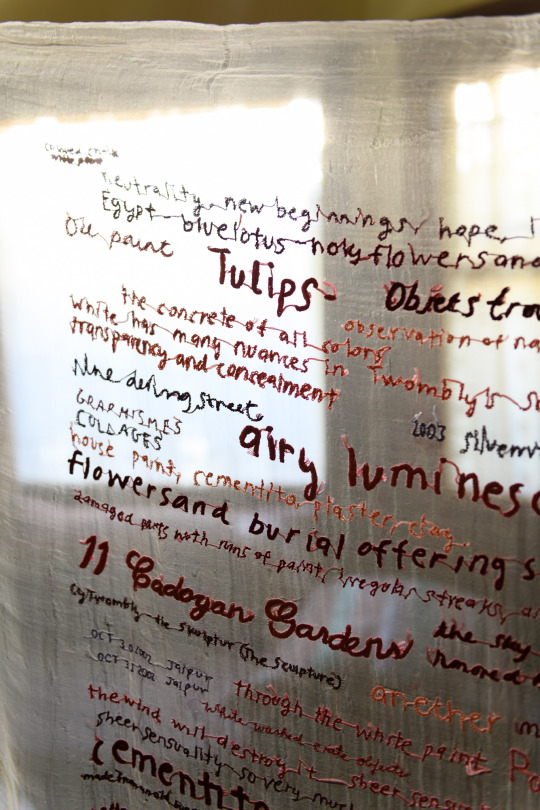

Artist Spotlight: Squeak Carnwath

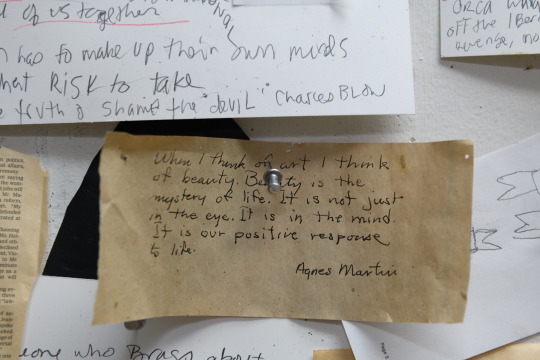

Our last interview of the year is with Squeak Carnwath, who has lived and worked in Oakland for the past five decades. Carnwath makes heavy use of text in her paintings: sometimes in a dreamlike way, as when you half-forget upon waking a phrase that seemed vivid in sleep; sometimes as subjective encyclopedia, as in her list-paintings of “pretty words” or “what we love about life”; sometimes in sprawling, philosophic lines that move across the whole canvas.

Despite all these words, Carnwath is hesitant to say anything definitive about what a painting might mean; and anyway there is not one meaning because we are always growing and changing, coming back to the painting a different person each time.

Studio AHEAD: In a great interview you did several years ago, you mentioned speaking less and less as you matured in your art. Yet your paintings often include words…

Squeak Carnwath: Paintings are about sensation and feeling; words are about talking, maybe about thinking, but paintings are beneath language. Paintings are the unseen language made visible. Also, I think that talking is more linear than a painting. Painting is the whole story. Words make up a story that are fixed in time. And I love ambiguity; it fuels creativity and intuition and allows the mind to wander in a beautifully guided way without an end or goal. Also, when I was younger I told stories about the work—particular stories about what started the work as if that was the end in the beginning. So it almost was like illustration, and as I got more into the metaphysics of painting, there was less need for illustration and more need to be open.

Studio AHEAD: One thing perhaps is that you are able to paint phrases that would be cliche if said aloud—ALL OF US WERE YOUNG ONCE, for instance—but somehow aren't when painted. Is this the magic of painting?

Carnwath: Yes, that is the magic of painting. Painting can turn the words into marks into images, scribbles, and scratches. Words in a painting are marks, marks that can make sense or can be a memory or a bit of a song in a painting. Writing in a painting can be a rhythm and add movement to a painting, like a pathway… like walking down a pathway. When you look at calligraphy in a different language, like in Persian miniatures, that’s as beautiful as any mark. And I don’t understand any of the Persian marks. So I love that about language, and it can go back-and-forth between being a thing and being an image. It can be water, it can be anything, but it can’t ever be a painting by itself. Sometimes it can be like a prayer.

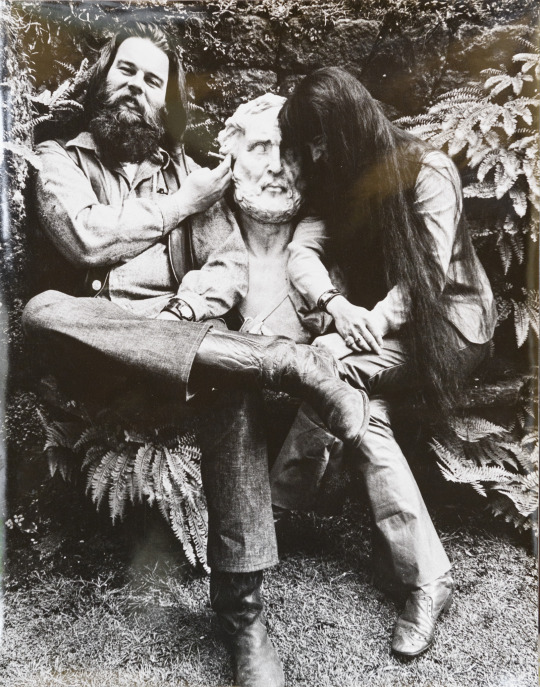

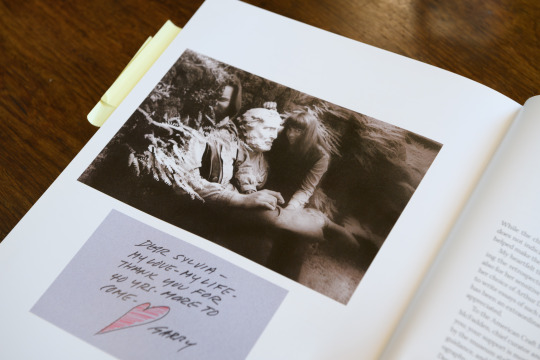

Studio AHEAD: I think what draws me into your paintings is that it gives the viewer permission to create their own interpretation. In Equations, the phrase "I just don't know" is written across the bottom of the canvas. This feels like it's always been your mantra when painting, to allow the imagination to meet the painting halfway. Carnwath: I do want the viewer-beholder to have the privilege and permission to interpret the painting through their own lens and lived experiences. What the viewer feels is also important and may not be something anyone can articulate, because a painting can come over you like a wave or later it can just tap you on the shoulder and it’s different every time you come to it. So it’s not set in one time because you’re not set in one time, you’re in the future, you’re always moving in the future; and so the painting goes with you into the future. Studio AHEAD: Equations also depicts a Garry Knox Bennett table. A few months ago we interviewed his wife, Sylvia Bennett [who has since passed away]. How did you become familiar with his work?

Carnwath: I’m not sure when I became familiar with Garry Bennett’s work, probably through California College of the Arts, and then we met a few times at various functions; and then we got to know Garry when we tried to buy the building that he had a studio in. It wasn’t for sale. We called up the owner and made an offer because it was the right size. The owner told Garry and he offered a bit more, so he bought the building. We ended up buying a building in the same neighborhood double the size, maybe more, and then Garry would always tell us that we got the better deal because we had more space. We had dinner with Garry & Sylvia on a number of occasions. It was always fun. Garry was provocative, to say the least, and of course I bit every time. But he had a great heart and so did Sylvia, and I miss him still. He was really multi-talented amazing.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#oakland#squeakcarnwath#squeak carnwath

0 notes

Text

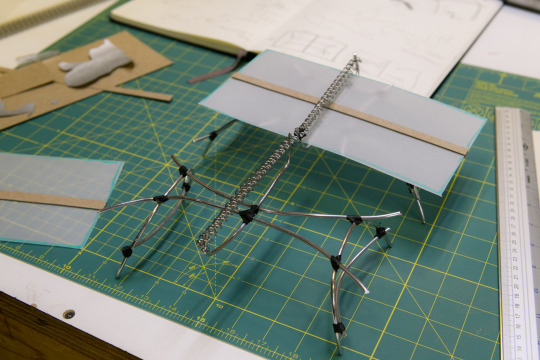

Artist Spotlight: Kate Greenberg

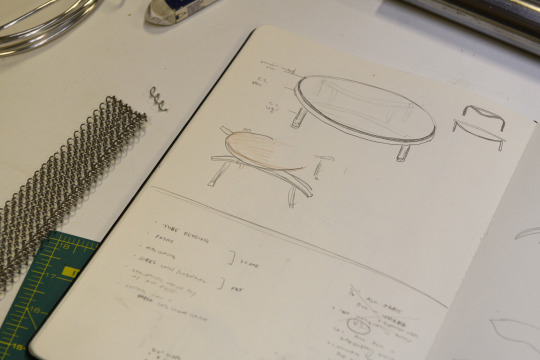

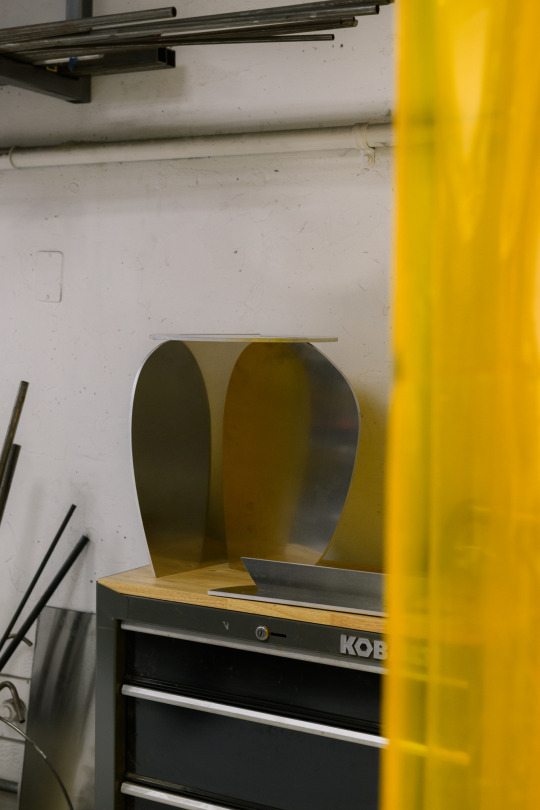

Longtime followers of Studio AHEAD know that a question we love to ask clients is “How do you sit?” because such a seemingly mundane activity has all sorts of cultural and physical assumptions behind it. This is a question furniture designer Kate Greenberg asks herself all the time. What’s thrilling is that she never answers definitively, instead presenting her work as possible non-answers.

For Californians there is the added pleasure in Greenberg’s designs of seeing how she sees California, whose topography unfolds subtly in her pieces. When we visited her studio in Alameda, she was working on something new, possibly a chair or possibly an entirely original way to sit on one.

Studio AHEAD: In your bio you say your furniture “suggests functions that are neither explicit nor expected.” What surprising ways have you seen your work used?

Kate Greenberg: Whenever I can, I design furniture that asks you to engage in a way that’s outside of the norm. I’ve seen the Tubie Chair used the most because it’s been around for the longest. With one armrest, it provides an opportunity for lots of motion over a sitting period while still being comfortable. I love to see how this chair is used at a dining table, because every single person sits on it differently. It’s like a posture opera.

I will never forget one particular delivery and watching the family gravitate toward the table and assimilate with the chairs in different ways. One person relaxed deep into that gap between the seat and backrest, and the other person naturally slouched, facing sideways to the adjacent person, with her arm slung over the backrest. Their kids started to climb on them and settled in by curling up on the cushion. There’s no designated carved seat you’re supposed to slide into, or a backrest or arms that hold you there. Sometimes those things are nice. But for this chair, I wanted a sense of freedom and comfort in one. Western dining chairs are usually meant to sit in one position, facing forward, which feels very Victorian if you think about it, and with the Tubie I really wanted to keep it open ended.

When I talked with reps about selling the chair over the years, they expressed that it would be too tricky to market as a dining chair; it just doesn’t fit the box. As a person trying to run a business, of course this isn’t so great, but you have to remind yourself there is power in taking risks and the right people will do that. When you offer new terms of use that people don’t immediately understand, you see that over time, these can become just as normal. Take the Windsor chair, now such a classic chair. I have many memories of my family’s Amish Windsor dining chairs as a child, listening to the sound they made when I slapped my hands one by one across the spindles, or getting my hand stuck in the gaps. Now this chair is accepted in the canon, but at some point, I’m sure people were confused how a bunch of thin wood cylinders would work well for a backrest.

A bit of a different approach to unexpected function: the lighting works I’ve made—the Radiator and Felled Sky—reference our daily rituals at home, the history of domesticity, and the rift between nature and our constructed world. The lights don’t exist to light up a room or a task, but instead hint to you where the sun is at in the sky, or give a psychological impression of warmth. Those lights people naturally flock to; they want to sit under the Felled Sky pendant and be immersed from below, or crowd around a Radiator light, like the gravitational pull of a bonfire.

Studio AHEAD: Do you feel constrained or freed by the form of the chair you’re sitting in now?

Greenberg: Well, to be honest, right now, I’m standing and writing, which is my preferred set up when working.

I do love chairs though, no surprise, and especially like to sit in chairs that give lots of options, with ways for your limbs to hang over, or ones that make you sit in weird ways. At home we have squatting stools, a wobbly active stool, and also this massive double-sided lounge chair I made. You can do a yoga bridge or sit back-to-back/head-to-head with someone. I cannot stand to sit in an Aeron chair or some sort of armed executive desk chair. It traps you into a position, and they really force ergonomics on you. In no way does that make for a dynamic experience with your body or apply to many bodies. This gets comfort all wrong (for me), invented at a time where they wanted you to shut off your body and give total focus to your company work. In short, I most enjoy sitting on chairs that don’t tell me what to do.

Studio AHEAD: Do you feel constrained or freed by form in general?

Greenberg: Form can be as freeing as you want it to be. I remember with Homan, one of the first long conversations we had, we talked about how our favorite way to hang with people at home was sitting on the carpet. Here we are, two designers talking about how their favorite piece of furniture is actually just the floor. Bad news! But we were recognizing that form can be constraining, and a great challenge to all of us designers is to keep poking holes in that. Researching Verner Panton while I studied furniture at CCA really blew that whole idea open for me.

In terms of my own design process, form is often the nucleus. It starts off as a sort of positive constraint, and never fails to be a big challenge to come up with a “new” form. That’s where craft-based thinking and working with material come into play, going back-and-forth in mind-centered and hand-centered processes, pushing an understanding of form outside of what you knew when you started.

Studio AHEAD: Share with us a recent problem that arose while designing and how you solved it.

Greenberg: Perfect timing—I was recently really strung out on designing this piece for our upcoming exhibition together. It’s a fairly large piece that requires a lot of heavy duty and some more traditional technique, because in my mind it absolutely needs to function the way it should. But I also wanted the piece to say something different about the game it’s about, and craft a story that I felt passionate about in lieu of my apathy toward the game itself.

I had to learn a ton about the requirements of this game, and how different materials react to each other in physics, in order to design accordingly. The challenge was how far I could push my concept without sacrificing the utility of the piece. I started to chip away at it by teasing apart the piece’s individual components, seeing how my concept could figure into each element, and then how the elements articulate each other in a comprehensive story. There were many circles of engineering; revisiting concept and lots of writing; design and form and material tests; and then back to engineering and starting over. By going through this cycle multiple times—instead of distilling concepts and then working out the fabrication—the concept only got deeper and I felt more connected to its purpose, which goes beyond using it as-is.

Ultimately, I think I was able to say something different about a “type” of furniture that doesn’t break norms, due to some very real technical stipulations, and I was very much emboldened by Barbara Stauffacher Solomon, who prompted the whole thing.

Studio AHEAD: We love Bobbie and are so happy to have your work shown with hers in our upcoming Same Blue as the Sky exhibition.

In another of our projects, we used your Lean Chair because the shape suggests the waves of the bay or the hills of the city. Is your work tied to place?

Greenberg: Having lived in the Bay for ten years now, and walking all over and thinking about how we got to inhabit the land as we do, the things I make always seem to have this layer embedded in it. My first love was architecture and first design activities were making site plans and elevations. When I moved to Northern California from New York, I became enamored with where the water meets the rock/grass/path/forest/mountains/desert, and how somehow, humans have woven structures around all this. The Lean Chair is about the weightlessness of a gesture, the strength of minimal material with just a swoop. There is something particularly San Francisco about it, the way architecture carves into the rolling land here, cascading in descending steps and giving way to the valley.

In the Lean Chair, the materials are also very tied to place: I sourced the elm from Arborica, from a felled tree that their team had just started to mill, so it was still very green and perfect for intense bending angles. I won’t go down the rabbit hole about how lucky we are to work with the trees in California, their resilience and diversity, but it was special to achieve the gesture I was looking for, out of a material that is itself a testament: strength and longevity are not synonymous to hard lines and rigidity.

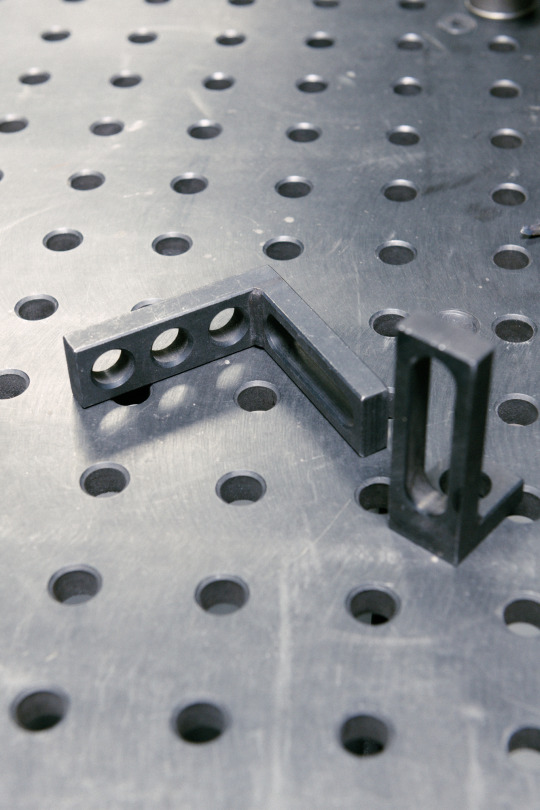

Studio AHEAD: Tell us about your studio space.

Greenberg: My studio is split. I design mostly from home, in a corner desk with few distractions. My fabrication workshop is an alcove within a shared space called Alameda Point Studios. It was originally a WWII-era hangar building that housed jet engines, but thirty years ago, Dean Santner—an incredible wood craftsman who’s been at it longer than all of us—and two others decided to turn it into a big woodworking production zone. He is still running the place with JP Frary, another wildly talented wood artist and storyteller. This shared shop is for woodworking primarily, and all the machinery is old and beautiful. I use this space for wood projects as well as mold making, casting, upholstery, material experiments…

It’s definitely a different type of space than I expected to land in, but very diverse as a home to cabinet makers, luthiers and piano repair experts, wood and printing press artists. I am the youngest and only one working in this particular niche of furniture design, and at times that can make me feel on an island, but I really love it and am so grateful to work there. My shopmates have persevered as makers through a decade or two or three, and this gives me a lot of promise that this life is possible. Most importantly, they really make me laugh when I’m having a hard day.

Aside from this communal wood shop, I share a metalworking space in a little upstairs nook, which used to be the control room when they tested military jet engines in the 40s. It’s pretty basic as far as metal fabrication equipment goes, but I’m able to make it all work somehow, with a few welders, a drill, lots of grinders and sanders, and a horizontal mill. I reckon we have the best finishing room in any shared artist space in the Bay Area.

Sadly, one day the city of Alameda will kick us out and start developing it. But for now, it is a second home for many craftspeople.

Studio AHEAD: Describe to us a collection you’d like to do that is also impossible.

Greenberg: I would love to design an entire furniture + lighting collection that is meant to be experienced in water and is made from water and underwater material. I think about and reference water all the time, but I wish it could be a main player in domestic life and in furniture.

Most of us live Earth-grounded lives, and build with material that is sourced from the soil and up. What would happen if you brought water, a vital element that takes up the majority of our planet, to the forefront of our daily experience? Water that meanders through the home, circulates in pools below the dining table, in moats around the interior perimeter. What materials would one have to use that could withstand being submerged every day? Would we look to some regenerative material of the deep sea? How would direct interaction with water every day affect the human experience? Obviously, humans are not meant to live in water day in and day out, and there’s all sorts of health, logistic, and sustainability concerns here, and this would never work. But it’s an interesting and weird future to think about, in a world with a rising sea level and extreme wet weather to which humans and their furniture have no choice but to adjust.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#interiordesign#oakland#kategreenberg#kate greenberg

0 notes

Text

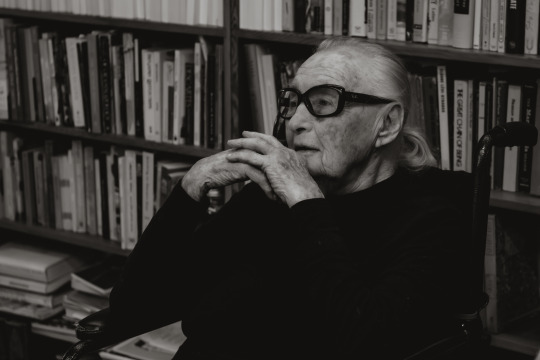

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: Northern California Legacy Spotlight

Last April, just before her death at 95, we had the privilege to interview Barbara Stauffacher Solomon, the trailblazing landscape architect and artist best known for her supergraphics inside Sea Ranch. Solomon, or “Bobbie” as everyone called her, was much more than her famous graphics, as her daughter Nellie, who helped parlay our questions to Bobbie, emphasizes.

Nellie King Solomon is an artist in her own right, whose gorgeous abstract paintings almost match the vibrancy of Nellie herself. We spoke with the two of them about memory and landscape, about love and what each has learned from the other, and about looking back on a life well-lived. Nellie’s daughter Fia joined in.

A few months after Bobbie's death, we revisited Nellie to ask what her mom’s legacy might be.

Studio AHEAD: Did California’s landscape influence your work once you returned from Switzerland?

Bobbie: It was the freedom of being a California woman that influenced you more than the landscape. Being in California as a woman was very different than being in Switzerland as a woman. I could do anything I wanted.

Nellie: I feel you, too, about the California woman thing and the freedom here having worked and lived in Europe and New York. I’ve come back to California multiple times as a result. There are hard-to-describe unspoken freedoms that are unheard of elsewhere. Even in New York. I would do things and be dismissed as “Californian”: make a drawing a certain way, have a different relationship to abstraction. At Cooper Union I would jump on top of my drafting table just so I could get a good look at my drawing from a distance. It seemed like the most natural thing in the world! Definitely a California move.

I would spend the weekends at Martha’s Vineyard looking at a seashell, stoned, and come back Tuesday morning with clear ideas about what I was going to draw for afternoon critique—that was a very different way of going about it. Slaving all weekend and sleeping under your desk was the East Coast Cooper way. Not for me. Go jump in some water and look at seashell instead.

Bobbie: About architecture, I see the corners of buildings and how they relate to each other. Supergraphics is all about relating everything to the corners. It never works having to do a computer printout ahead of time. It doesn’t work because it’s all about tying the graphics to the corners, which is on site. The architecture tells you what to do.

Studio AHEAD: The contrast between the colorful, geometric quality of Sea Ranch’s Supergraphics and the rolling hills and waves of Sonoma is very striking. Was this on purpose?

Bobbie: I didn’t want it to stick out. I didn’t want it to be more visible than the landscape itself. Well, it is but it’s indoors.

Nellie: You were doing the Supergraphics indoors so that it wouldn’t stand out against the land and look obnoxious. That’s why there’s all those rules up there at Sea Ranch—that whole dictatorial handbook that comes with the property that says don’t plant a rose or do Supergraphics outdoors. Your stuff is brazen but it’s inside.

Bobbie: Like once I was teaching at Sitka, Alaska and a woman wanted me to paint the main street with Supergraphics—this little town. I said “No!” with vengeance.

Nellie: I remember the walk through the forest and the ancient weathered totem poles and you would let the students paint inside the ugly fluorescent lit hallways. You wouldn’t let them paint outside in the beautiful quiet forest.

Studio AHEAD: What is one of your works that you’d wish had gotten more attention?

Bobbie: Graphics at the San Francisco Museum. It’s the biggest artwork in the museum that a woman has ever been allowed to make. And what does that mean? There really hasn’t been any press.

Nellie: And you’ve been annoyed about that. It’s bigger than a football field, and stronger in a way.

Studio AHEAD: Nellie, you help your mom with these large installations. What have you learned from her?

Nellie: Be big, bold, and beautiful. Be brazen. Think of the whole space and really go for it. These are all things that come in the territory of helping my mom do what she does. They definitely have rubbed off on me. To think of things from the perspective of the negative space, as opposed to the positive space, that’s a more formal quality. I think of the principles that she learned from Armin Hoffman. What I absorbed in watching her put together and draw Green Architecture and the Agrarian Garden when I was in fifth grade. So many gardens Bobbie and I snuck into all over the world. That there’s a certain irreverence and physical relationship to space and making that I’ve adopted from working with her.

I learned a lot of stuff from her and that would be very hard to figure out. It’s like untangling pantyhose that has been in a drawer forever. It’s all tangled up. And then some stuff I learned from Cooper Union and then some stuff I learned from Hoffman. I mean where does one education start and another education begin? What stuff did you learn from which grandmother or which parent? These influences are all different voices mixed together and yet when you get in your studio—there’s a great quote—when you close the door to your studio, you have to kick out all the voices and then begin.

Studio AHEAD: Bobbie, what has Nellie taught you?

Bobbie: What has Nellie taught me when you have a kid you love? You just learn how to try and make them happy.

Studio AHEAD: Fia, what’s going to be your medium of choice?

Fia: I'm a singer-songwriter, writer, and aspiring actress. I have an idea. I think that the youngest one should ask a question to the oldest one. I want to ask Bobbie, Why is your imagination at the end of life so opposite to your work?

Bobbie: You smart little thing!

* * *

Nellie: At the end Bobbie saw all of these romantic, fanciful, green, growing vines all over the ceilings and over the whole house. At one point the house turned into a hot-fudge sundae with different shades of light, dark, and milk chocolate for all the shadows. All these romantic and wild, elaborate visions would appear over the white walls of the clean, modernist house where she lived. Entirely opposite to the stark hard-edged graphics she was known for. That’s why Fia asked her question and why Bobbie knew it was wise.

Bobbie always loved the “schmaltzy” as she would call it. The romantic gardens, the formal gardens, the Tuileries, France, Turner Classic movies, Hollywood plots. When we wheeled her up to the entrance of SFMoMA to see her Strips of Stripes exhibition from the revolving doors, there was, flanking her work, two large Julie Mehretu works: “Ah, those are real art. The kind of stuff I would’ve made if I didn’t have to make money.”

As she lay dying in a magical space, her imagination ran wild on the stark white ceiling. She was enveloped in a romantic fantasy, ever-changing, constantly urgent to describe it to me, or anyone who would listen, as she slipped between worlds.

* * *

Studio AHEAD: What do you think your mom's legacy will be?

Nellie: There’s a chance that Bobbie’s Northern California legacy continues to be Sea Ranch. Bobbie does not see herself as defined by Sea Ranch at all. She is much more interested in her books and her continual evolution. Bobbie has a much more complex legacy than that one early project. She has multiple voices: hard-edge Supergraphics, complex books like Good Mourning California, the Green Architecture and the Agrarian Garden landscape drawings in the 80s.

She continually reinvented herself. Which made it tricky to pigeonhole her into a discipline or a style for a final summation, but it’s also her brilliance. In a 1968 Vogue issue, Bobbie (and her friend, the film critic Pauline Kael) were named “two of the 20 (?) women most in touch with her times.” Bobbie continually stayed “in touch with her times” by evolving with the times.

Studio AHEAD: What has been the reaction since her passing?

Nellie: People’s reaction is with a certain sense that Bobbie is immortal. It’s a funny thing. A dealer she worked with said “it seemed like she would never die. She couldn’t.” Even as she got old, she said “who you calling old?” Fia and I have decided not to refer to Bobbie in the past tense. We refer to her in the present tense. “Bobbie is” as opposed to “Bobbie was.”

There’s an outpouring of caring. It makes me want to invite everyone to be together in her honor, and onward. Bobbie lives in us. Bobbie is not at all gone.

“To be is not to know what to be”—this is one of my favorite things she wrote. If she is not being, then she now IS. Perhaps this is why galleries prefer to represent estate artists. Quantifiable only after death.

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#bayarea#art#northern california#studio ahead#california#artistspotlight#san francisco#nelliekingsolomon#Barbara Stauffacher Solomon#BarbaraStauffacherSolomon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Spotlight: Elana Cooper - Creativity Explored

In 1983 Florence and Elias Katz founded Creativity Explored, a studio that helps artists with developmental disabilities discover and foster their talents. Four decades later, the organization is still putting out exciting exhibitions and making space for people who have historically been left out of the picture.

When we visited the studio earlier this year, we were arrested by the flower paintings of Elana Cooper. With the help of Creativity Explored’s staff, she answered some of our questions and shared with us her imaginative world.

Studio AHEAD: How did you get started with Creativity Explored? Have you always been an artist?

Elana Cooper: I forget what year I started—Eric knows. When I came here I liked it a lot. I learned how to draw animals, then I learned how to draw flowers, and I kept doing flowers. I went to a different art school before Creativity Explored but only for one day— I didn’t like it.

Studio AHEAD: What does a typical day look like for you when you’re making art?

Elana: I’m really fast in the morning. [laughs] I get tired in the afternoon because of my medication. I have epilepsy and I get tired from it.

Studio AHEAD: Tell us a little bit about your flower paintings.

Elana: I work from a picture, and then I draw it, then I paint it after. Sometimes I do big, big ones, and I do medium size all the time. Like now, with Tom, I’m learning to do a door, with flowers, a patio, a background of trees. Yeah, I’m doing art now with Tom. It’s different with each teacher, I see it a different way now with Tom, he’s helping me learn it.

Studio AHEAD: One thing I find striking about some of these flower paintings is your use of the color black, because flowers aren’t naturally black. Why did you choose this color?

Elana: Paul started it. In the gallery, I got into it, and everybody liked it, then we called it “Flower Power.” I do more black, and I’m trying to get more color into it now too. Now with Tom, I’m doing stuff differently. I’m learning on it.

Studio AHEAD: What’s your favorite flower to paint?

Elana: Any flower.

Studio AHEAD: Do you consider yourself an artist now?

Elana: Yeah, I got a lot of money now. I’m going to London, and LA for Disneyland.

Studio AHEAD: Do you paint at home or just here at Creativity Explored?

Elana: Here. I don’t do it at home. I like doing word searches.

Studio AHEAD: Are you interested in working with other materials besides paint?

Elana: No [laughs]

Kelsey: So you’re a painter through and through.

Elana: Yeah!

Photos: Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#art#california#artistspotlight#interiordesign#san francisco#oakland#creativity explored#elana cooper#elanacooper

0 notes

Text

Ann Hatch: Northern California Legacy Spotlight

Ann Hatch has had many lives: ceramicist, entrepreneur, philanthropist, visionary founder of the Capp Street Project and the Oxbow School. “I believe ideas and projects have a relevance at a certain time… Things change. It is important to know when it is over,” she said to us, reflecting on a decades-long career that no matter its form has always centered on the arts, even as the city and the scene changes.

The other great constant in Hatch’s life, besides art, is her curiosity for culture. This was abundantly clear when we visited her home in Sebastopol earlier this year. Designed by her ex-husband, the architect and Buddhist priest Paul Discoe, the house is itself a work of art, with obvious Japanese influences and a respect for the materials, often left in their natural state. What makes this house Hatch’s own, however, are the artworks throughout—so perfectly selected that it is no surprise why Hatch has had success through all her personal reinventions.

Studio AHEAD: Years before we met, I came to your Sebastopol property—I didn’t know it was yours at the time—to pick up a piece by Jesse Schlesinger, who was living there. Tell us about this house, which was designed by Paul Discoe.

Ann Hatch: Designing and building a house with Paul was a unique experience. He had just started his construction business. Everything was done in the Japanese tradition. We had a terrific time designing and planning. We both had wild ideas. He could do them and make them unusually beautiful. When the project was finalized, we realized we really wanted to be together. Since we were both married that took some time. Paul is one of the most creative designers I had ever met—nothing was impossible. We shared a love of wood and using materials in creative but functional ways. He designed and built the New York apartment, as well.

Studio AHEAD: Do you regularly open up your home to artists?

Ann Hatch: There was a time when I had lots of receptions and parties. Now, I invite assorted people for small gatherings, mostly to the ranch. It’s fun to show them the details and materials of the house. I have, like everyone, realized how important my friends are. One benefit of getting old is the depth of friendship that we have.

Studio AHEAD: Is this the same kind of energy that pushed you to found the Capp Street Project?

Ann Hatch: I started Capp Street unexpectedly. I saw a David Ireland-designed house, which was for sale, empty. I met him on his birthday. I had a lot of apples in the car, which I took over to his personal residence to meet him. I soon agreed to buy the house he designed at 65 Capp Street without really knowing what I would do with it. But I knew it was a special space: I liked the changing light and sculptural elements, especially when it was empty. I knew the house could be a springboard for new ideas, not just a house. It was an immediate decision that you can’t explain. All my projects have started with a burst of confidence. I just knew it was the right idea for that time and needed to be done. I was fortunate to have the resources and advisors to get these projects started. In all cases my intention was that the project would be sustainable. It worked pretty well back then. (Things are different now).

Interestingly, my great grandfather T. B. Walker started the Walker Art Center out of his house. Maybe that had imprinted on me in some deep place. I moved quickly to develop the concept for an artist-in-residency, which was a new idea back in 1983. Artists were very enthusiastic about coming to San Francisco and making new work. We got the bravest and the best of the installation artists. Initially they made loose proposals; it was expected they would use S.F. or the house as a source of inspiration. I learned a great deal about Bay Area history from their projects: shredded money came from our mint, razor blades made from requisitioned cannons in the Presedio, seismic activity, recycled paper from Recology, and what people discard on the street. One collaborative team put fish hooks on all the street detritus around the building. We all had so much fun and realized amazingly bold ideas. The word spread fast among the artists—we were real and could do stuff! We facilitated the artists wishes, and that was thrilling.

Studio AHEAD: Could you have started Capp Street anywhere or was it something unique to the feel of San Francisco at the time? Perhaps it wouldn’t even be possible in San Francisco now.

Ann Hatch: Honestly, I would never be able to do a Capp Street project now. Everything is so charged and PC. I was born in S.F. and feel it has amazing qualities and depth. I wanted to see what artists would find interesting and worth focusing on. It might have worked in Chicago or any big city. Our artists, after 15 years, told us they were getting museum and gallery opportunities, which was great and why we closed. I believe ideas and projects have a relevance at a certain time. They can adapt and change sometimes, but it’s OK to "sunset" projects.

Later, I started Oxbow School in 1997, which we are closing after 25 years. I also closed Workshop Residence after 9 years when the pandemic hit. Things change. It is important to know when it is over.

Studio AHEAD: In the 80s and 90s you put on wild shows in your gallery: in one, the artist purposely flooded the exhibition space; in another, the street was extended right into the gallery, so that you couldn't tell which was interior/exterior. You have a much more adventurous, exploratory spirit than most patrons....

Ann Hatch: In the 80s it was a more adventurous and free time. There were lots of non-profit spaces that did great programs. The artists always wanted tech and unusual materials, which were difficult and challenging to find. Each residency exhibit was completely different. Capp Street Project had t-shirts that said "Weird things in a big room.” We had a small budget with lots of friends and connections. People wanted to be generous and part of these projects.

Studio AHEAD: What drew you to Napa to start the Oxbow School?

Ann Hatch: I was meeting the Mondavi family with a friend who was writing Robert Mondavi’s biography Harvest of Joy. My friend wanted to pitch Mondavi to fund a TV series of artists talking about their work. I said "no, that's a dreadful idea. Artists should not talk about their work… if I were Mondavis, I would start a school." So I was invited up to lunch… many lunches. I showed them many ways the arts can enrich young people and the community. He wanted to do something in the town of Napa that would have national impact. I quickly bought 15 pieces of property that were in the floodplain. It was across the river from his big project, Copia: The American Center for Wine, Food, & the Arts, which made it an "arts" district. Acquiring the properties was easy, as all the owners wanted out of the floodplain. The idea of having a semester for high school students with an arts focus was unique. Subjects taught in tandem with academics: English with painting, math with sculpture, for example. New ways of getting students thinking and engaged. Again, a bold idea that had its time. Oxbow did it really well, as the students say that I’ve changed their lives. I'm very proud of that.

Studio AHEAD: Twenty years ago you did a fascinating interview with Richard Whittaker and gave a great piece of advice to young artists: “You've got to be centered in what the work is about.” How have you remained centered in your own work?

Ann Hatch: That sounds preachy. I was probably thinking about the students at Oxbow School. If we could get the students focused in creative ways, they really blossomed. I have had the opportunity to start three projects. I've needed to be very focused on those to have them realized. Personally, I'm a bit hectic. I try to do too many things. That’s changing now...

In The Dogpatch you had Workshop Residence. Elena came after class from SFAI to a workshop headed by Max Lamb. Tell us about those times. Again I developed a plan for something that did not already exist. I wanted to have a store with limited editions of objects and work made by artists. Again , we rolled up our sleeves and made things with artists partners and fabricators. rugs made out of fire house, Sol Le Wit blankets, coffee cups made by 3D printing coffee grounds,, door stop made from skateboards, Perfume made locally, knot tieing Indigo and broom makingtied workshops, broom making,.etc

Studio AHEAD: Let's say I am a young person of certain means who wants to become a patron. What advice would you give? What has been most useful in your career?

Ann Hatch: Try new ideas that are within your means. Research what exists and find a niche. Be bold in concept. Use your friends and contacts. I needed an army for all my projects. It is one of the good parts of getting older, you have deep friendships. If you have financial resources, don’t be shy about using them in a constructive way. Starting projects takes energy, vision, and money. That’s nothing to be embarrassed about. I wanted to keep a low profile. Maybe that’s not possible now? If you’re making an impact, the word gets out by your deeds. Not social media.

Studio AHEAD: In a career of constantly looking forward, what is next for you?

Ann Hatch: I think my ceramics will hold my attention. I can control the whole process and keep learning. No board of directors, staff, or committees. I am enjoying doing porcelain portrait dog and cat bowls. People are crazy about their pets. They should have beautiful dinner dishes. It’s fun to capture their charming distinct expressions.