Text

Jonah! Your video essay was delicious. I'm particularly interested in how you speak of Zola and Stefani as dialectical opposites, whose performances of race relate to one another--your point about the visual storytelling, the bravado, the glitz and glamor making immanent a world stringently invested in gazing and making real its raced subjects as the products of this gaze, of a postmodernist technological categorization, is compelling and strong. It makes me think about how Judith Butler distinguishes between "seeing" and "reading," the former being an impossible ideal of a neutral way to view an object without projecting culturally-sanctioned thoughts and values onto them, and the latter being the way these thoughts invest us with ideas about what we see--your reading of the character of Zola investigates these ideas and how Stefani (Money, titties, money titties!) determines her visibility and imitates her Blackness as a function of this racial reading.

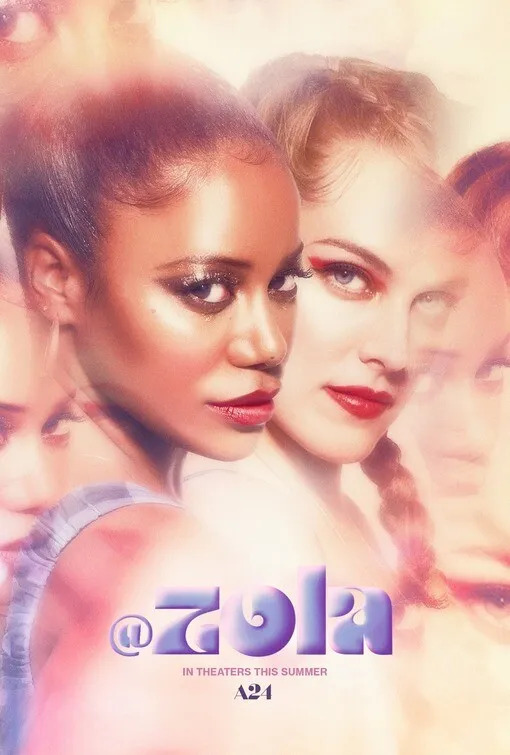

Zola: Digital Storytelling and Racial Performance

“Y'all Wanna Hear A Story?...”

Zola is a glittering piece of postmodernism, filtering the infinite jest of touch screen technology through the medium of film. This is appropriate, considering its source material – a 148-Twitter thread from 2015. Narrated with lacerating wit by Aziah “Zola” King, the thread details the Detroit-based waitress’ wayward excursion to Tampa. Packed with suspenseful twists and turns, it's only natural that it eventually became a feature length film. After years of middling in development hell, Zola was eventually released in 2020. Directed with auteur sensibilities by Janicza Bravo, Zola uses a road-trip from hell to interrogate (or subvert) American race-relations, transaction and bodily autonomy.

The plot unfolds on the heels of a newfound friendship. Zola (the magnetic Taylour Paige) meets Stefani (Riley Keough) at her waitressing job and the two strike up a bond. Both strippers on the side, they appear to be cut from the same cloth – funny, street-smart hustlers and practitioners of a particular brand of femininity. This femininity is one patterned off of Black womanhood and Stefani, who is white, is shameless in her racial posturing. With stray braids, slicked down baby hairs and the unmistakable accent of a white girl imitating Blackness, Stefani represents a post-racial spectacle of appropriation. Keough delivers a comic tour-de-force performance, ringing each AAVE-inflect line with the appropriate amount of misplaced conviction. That Keough is the granddaughter of Elvis is not really relevant, but it does add just a pinch of subversiveness to the proceedings.

Shortly after they meet, Stefani invites Zola to strip with her in Tampa. Joining them are Stefani’s misbegotten beau (Nicholas Braun, giving a masterclass in patheticism) and her enigmatic, increasingly shady “roommate” (Colman Domingo). Zola comes to discover that she is in the throes of a trafficking scheme and that Stefani’s intentions may not be as innocent as she proclaims them to be. In her essay “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance,” author/academic bell hooks writes of cultural appropriation and its manifestation in the media at large. She writes that, “The overriding fear is that cultural, ethnic, and racial differences will be continually commodified and offered up as new dishes to enhance the white palate – that the Other will be eaten, consumed, and forgotten.”

In many ways, Zola functions as a story of otherness – specifically White consumption of the other. Stefani is the walking embodiment of white consumption and continual exploitation/coercion of Zola only emboldens this quality. Zola, on the other hand, is expected to look out for Stefani, opining at one point, “Who’s looking out for me?” This line is indicative of Zola’s compromised safety as a Black woman – a figure who is expected to take care of everyone but herself. When Stefani tells her pimp that, “Zola made me a whole new bitch,” she is literally referring to Zola’s help in increasing her net value in the realm of sex work, but more implicity speaking her debt to Black womanhood as a means of adornment.

Zola and Stefani are depicted as mirror images of one another, both literally and figuratively. Bravo follows in the footsteps of many a psychodrama in her choice to present the two as spiritual twins. Walking down a hallway in corresponding outfits or gazing upon their reflections, they are both augmentations of one another and so completely diametrically opposed.

Elsewhere in her aforementioned essay, hooks states that, “Cultural appropriation of the Other assuages feelings of deprivation and lack that assault the psyches of radical white youth who choose to be disloyal to western civilization.” This feels like an appropriate diagnosis of Stefani, someone who exists outside of white parameters and thus adopts Blackness in relation to her perceived outsider status.

Bravo has described her films as existing a step-away from reality. This is fitting for a film like Zola, which renders a stranger-than-fiction story into filmic material. In a profile of Bravo for The New York Times author Jenna Wortham wrote:

Her movies are reminiscent of being on psychedelics — the way even the most mundane interactions become revealing, exquisite and worthy of intense examination, and the way something humorous can seem sinister for a flicker of a second before shifting back into levity. Bravo specializes in exploring the way seeing clearly can happen in an instant and permanently alter your experience of yourself and your life.

Bravo walks a tonal tightrope, but through the imaginative force of her storytelling, manages to pull it off.

Shimmering in neons and buzzing like a smartphone, Zola occupies a distinctive sonic and visual landscape. There are qualities that seem like a callback to old Hollywood: orchestral swells and grandiose title cards. These stylistic nods come across a little cheeky, especially considering the ways in which Zola rejects the Hollywood formula. Aided by playwright provocateur Jeremey O. Harris (who co-wrote the screenplay), Bravo presents a narratively frenetic fever dream that sidesteps convention at every turn. Even though Zola is unequivocally the narrator, the nature of authorial authority is subverted in a sequence where Stefani speaks to the camera, telling her side of the story.

In the Western sphere, stripping is one of the more fascinating, and literal, representations of our bodies’ entanglement with capitalism. The physicality, the need to appease and titilate, the showering of dollars. All of it seems like a particularly charged ritual of commerce. Zola does not incriminate the profession nor does it glorify it. For the titular character, the act of stripping has an autoerotic verve to it: through it she is able to explore the dimensionality of her selfhood. This is most evident in a sequence in which Zola envisions the different personas she can adopt before a performance. Repeating, “Who you gonna be tonight?,” she appears in multitudes, as if in an elaborate musical number (yet another moment that made me recall the stylistic grandeur of Old Hollywood).

If this moment is any indication, Zola is a film in which pleasure and pain are offered up with equal aplomb. It is a disorienting and spellbinding exercise in absurdism, confounded by the fact that its story is ripped from the digital headlines.

Work Cited:

bell hooks, “Eating the other: Desire and resistance.” In Black Looks: Race and Representation, pp. 21–39. Boston: South End Press, 1992.

Wortham, Jenna. “How She Transformed a Viral Twitter Thread about Sex Work into a Sinister Comedy.” The New York Times, The New York Times Company, 16 June 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/06/16/magazine/how-she-transformed-a-viral-twitter-thread-about-sex-work-into-a-sinister-comedy.html.

@theuncannyprofessoro

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm really interested in your point about the use of archival footage in montage as a "metric overtonal" element of the film--the way it disrupts the audience's comfort and reminds them that this is not merely a fictional account of Tekahentahkhwa and her family but a very politically grounded representation of a real genocide. Montage can be so powerful visually as a tool to evoke emotion in viewers and provide them with a lot of visual information in a short amount of time to elicit feelings and tell a whole story in a short amount of time.

Beans Critical Analysis

youtube

Beans (2020), directed and co-written by Tracey Deer, is a semi-autobiographical film that follows Tekahentahkhwa (“Beans”) during the Oka Crisis (July through September of 1990). This violent conflict between a group of Mohawk people and the town of Oka in Quebec, Canada, in a way, began centuries before when the Mohawk (the most easterly section of the Iroquois Confederacy, located in southeast Canada and northern New York state) first settled in the area in the late 1660s1. However, this specific event arose because “The Pines” (indigenous land) and a nearby Mohawk cemetery were to be cleared to expand a golf course and build new condos. While not all residents of Oka supported the plan, the mayor refused to discuss and hear from the people. By the end, the crisis was successful in halting the development, but resulted in two killed and over one hundred wounded.

Tracey Deer, who was born and raised in Kahnawake (one of the Mohawk communities in the region of Oka), was 12 when she lived through this crisis. In the grand scheme of things, there are very few who could be entrusted to create a film on this specific event, and luckily, Deer is one of those. This won’t be a tale of the white savior entirely misunderstanding and misrepresenting colonization conflict! A nice change of pace.

Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory is at the heart of this film. It’s centered around an undeniably racialized conflict: First-Nations (and their supporters) vs. Colonizers. But, as mentioned previously, this is co-written and directed by a Mohawk woman who grew up in this community and experienced this conflict first-hand (the other writer is Meredith Vuchnich and it seems as though she is not indigenous). As we all know, relations between indigenous populations and settlers around the world are violent and oppressive, to say the least. Speaking for myself, I am most familiar with the North American history and from what I know, it is relatively representative of global indigenous genocide. So, what is so special about this film is that it is a coming of age story that takes place during a widely unrelatable historic moment and proves that the fight for sovereignty is not over. We’ve all been Beans: should she go to the private school she was accepted to? Are her new friends good for her? But also will her community succeed in the protection of their land? Deer sets the story during a somewhat recent conflict, proving the battle for sovereignty is not over as some might like to believe. In their article “Colonialism, Racism, and Representation: An Introduction,” Stam and Spence write that “[a]n ethnocentric vision rooted in North American cultural patterns can lead, similarly, to the ‘racialising’, or the introjection of racial themes into, filmic situations”2. I would argue that Beans is a functional execution of this idea: Tekahentahkhwa is just a pre-teen coming into a difficult world as she witnesses Canadians and their government fight against her existence and right to save her land. Stam and Spence also write specifically about indigenous populations, arguing that the “attitude toward the Indian is premised on exteriority”2 and the “besieged wagon train or fort is the focus of our attention and sympathy, and from this center our familiars sally out against unknown attackers characterized by inexplicable customs and irrational hostility”2 (2009, 759). While this is true in wider film history, I would argue that it is only partially true in Beans because Deer brings us onto the reservation and into Beans’ family. We’re not viewing the Mohawk community from the outside and watch them be victimized by white Candians. The viewer does not pity them and is more familiar with the attackers. However, it is clear that the hostility of the Canadians is irrational and wildly disproportionate (considering there should not have been a conflict in the first place because they were proposing to steal even more Mohawk land). Deer deftly navigates a relatable coming of age 90s story and the experience of indigenous women and populations in modern history.

Montage Theory

Another theoretical approach that this film utilizes is the montage. I love a good montage, especially if it makes use of archival footage of historical events, and Deer does this flawlessly in Beans. She intercuts the narrative with footage of the actual protests to provide context and transition during the film. If we follow Sergei Ėjzenštejn’s Soviet Montage Theory, I would argue that Deer employs a metric overtonal, not just tonal, montage, because “movement is perceived in a wider sense”3 and it’s “based on the characteristic emotional sound of the piece,”3 but “it is distinguishable from tonal montage by the collective calculation of all the piece’s appeals”3. Furthermore, these archival montages are “capable of impelling the spectator to reproduce the perceived action, outwardly,”3 meaning Deer is looking to evoke an emotional reaction as the viewer is confronted with undeniable, clear evidence of the vitriol and hatred of the white Canadians. Through it direct confrontation, Deer sets a emotional tone, lest the viewers forget that Beans is not simply a coming of age film: Tekahentahkhwa and her family are battling a centuries-long genocide, something that most pre-teens are unfamiliar with. The structuring and score of almost every single montage is identical, creating an overarching tone conveyed by her. Many of these montages are accompanied by the newscasters’ voiceovers and a tight, quick, string-heavy score, almost reminiscent of a horror film, which I believe sets the consummate haunting tone and reveals the “psychological turmoil of [the] characters”4.

Beans is an amazing movie about an event that I, hate to admit it, had never heard of. I loved how Deer balanced a coming of age story with a violent crisis that is simply one event in a long history of colonial oppression by white settlers. Viewing this film through the lenses of Critical Race theory and Soviet Montage theory enhances her storytelling abilities and allows the viewer to melt into Beans’ world.

Sources:

Ėjzenštejn, Sergei. “Methods of Montage.” In The Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, translated by Jay Leyda, 72-83. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1949.

Melinda, Meng. “Bloody Blockades: The Legacy of the Oka Crisis.” Harvard International Review, 30 June 2020. https://hir.harvard.edu/bloody-blockades-the-legacy-of-the-oka-crisis/.

Pudovkin, Vsevolod. “From Film Technique [On Editing].” In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, 7-12. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Stam, Robert, and Louise Spence. “Colonialism, Racism, and Representation: An Introduction.” In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, 751–66. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I loved your video essay and also used Halberstam's conception of ideological positivity to help frame my analysis--I thought your point about what we expect from masculinity and butch lesbians being rooted in their lived reality and the "stereotypes" it proliferates being a consequence of the broader culture was compelling. It makes me think about the genesis of the "stereotypical lesbian" and how much we risk overwriting the realities of people aligned with these presentations by disregarding them as stereotypical.

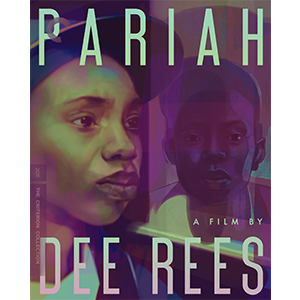

Pariah - Dee Rees (2011)

Engaging with film and media gives the public an opportunity to get to know people, places, and identities that they wouldn’t necessarily encounter in their own lives. Because of this, there are great steaks in the way that we represent people, particularly those who have been oversimplified, minimized or left out of stories completely. There are hugely necessary conversations happening about representation in film, the goal being to humanize people and refrain from perpetuating negative stereotypes that hold back representational progress. But what do we mean when we say “positive representation” and “positive imagery”? Do stereotypes always equate to negative representation? Dee Lee’s 2011 film Pariah breaks down some of the rules we have created about representation and shows us characters that expand stereotypes rather than rejecting them completely.

Pariah tells the story of 17 year old Alike coming to terms with her lesbian identity, navigating her queerness in the world of high school dating as well as in her religious and homophobic household. Alike’s best friend Laura – butch, sexy, confident, and much more romantically and sexually experienced than Alike – is attempting to help Alike break out of her shell and meet someone. Laura has not spoken to her mother in months and is living with her sister, working to support them, and attempting to get her GED so she can take on more responsibility. I find Laura’s story and her friendship with Alike to be really compelling and significant surrounding conversations of queer representation. Laura and Alike’s friendship is perfectly balanced with tenderness and tough love. When Alike decides that getting a strap-on would benefit her “image”, she goes to Laura and asks her to get one for her. Laura lovingly laughs at Alike and without question agrees to help. They stand together in the mirror as Alike reluctantly tries it on, Laura cheering her on and reassuring her that she looks good. There is something that is very sweet about this moment, evoking the innocence of a coming-of-age friendship, awkwardly helping each other navigate the constant newness and uncharted territory of their teenage lives. We continue to see moments like this where Laura and Alike, who are both forced to harden themselves to manage the intensity of their family lives, soften up with each other. When Alike starts having a romantic relationship with Bina, a neighborhood girl who her mom forces her to start hanging out with to keep her from Laura, Laura comes to Alike with concern about drifting apart. She tells Alike, “I just want to get this off my chest. I’m glad she makes you happy. I’m happy for you. Cause I love you.” You can tell on Alike’s face that she is shocked to hear this. You can see on Laura’s face that this kind of expression is difficult for her. The real turning point in our understanding of Laura is the first time we meet her mom. Laura comes to see her and nervously attempts to get everything out. She tells her she got her GED and that her and her sister are working hard and making her proud. Her mother says nothing before shutting the door and going back inside. This is a really significant moment for Laura because up until this point she has never seemed to care what anyone thought of her. We realize here that there is one person who she will always be trying to impress. She stands outside her mothers door panicked and in tears. All she wanted was her recognition and approval.

I think a lot of concerns around queer representation frame the existence of stereotypes as inherently negative, fighting for queer characters who are doing something different. In his book, Female Masculinity, Jack Halberstam questions what we really want out of queer characters and what gets to be positive representation. “Positive images, we may note, too often depend on thoroughly ideological conceptions of positive (white, middle-class, clean, law-abiding, monogamous, coupled, etc.)” Laura’s character rejects the idea that positive representation of queerness has to be those things; representation of Black female masculinity is such an important subversion from the power and respect that is glued to images of white male masculinity. She holds with power and strength her identity as butch lesbian of color: she is tough, self-assured, popular with femmes, and uninterested in what anyone thinks about her. She is also not diminished to those qualities alone. She is sensitive, intelligent, complicated, she takes her life seriously and has a thoroughly explored, trusting and deep friendship with Alike.Without the moments of vulnerability and openness I described, Laura may have been passed off as a side character, and therefore reduced to some of her more surface level qualities. The times in which stereotypes are negative are when they are diminishing and when characters are not allowed real depth and character development. Halberstam explores the most common queer media stereotypes, “the butch” and “the queen,” pushing back on the assumption that when we encounter butches and queens we are encountering a homophobic narrative. “It is important to judge the work that the stereotype performs within any given visual context-accordingly, if the queen or the butch is used only as a sign of that character's failure to assimilate, then obviously the stereotype props up a dominant system of gender and sexuality. But often the butch or the queen exceeds the limits of representation imposed by the law of the stereotype and disrupts the dominant systems of representation that depend on negative queer images." Butchness, framed simply as a stereotype, denies it any validity as a true and authentic identity.

Laura’s character is a strong example of positive queer representation because she owns her identity and breaks down walls that are so often formed around characters like her. Her character owns a stereotype without presenting it as a failure to be more. The problem with representation in film is that certain characters are not afforded the opportunity to display their “more”. Framing stereotypes as a form of negative representation can be a dangerous narrative. Leaving butchness out of queer stories to avoid stereotypicality depends on butch identity as a negative queer image. Instead of rejecting stereotypes wholly, we should be doing work to make sure we give our minority characters the opportunity to be known fully, to have flaws, and to still be cared about.

Works Cited:

Halberstam, Jack. Female masculinity. Durham (Grande-Bretagne): Duke University Press, 2018.

@theuncannyprofessoro

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Watermelon Woman: Queer representational strategies as possibility

Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) made history as the first feature film written and directed by a Black lesbian–but the film knows this and extensively explores its appellation as the “first of its kind,” a title Dunye simultaneously treats with frustration and reverence. It’s strikingly self-aware, funny, and inventive, a semi-autobiographical story about Cheryl, a video store clerk and chronically single filmmaker who decides to make a documentary on a mysterious Black actress from the 1930s pigeonholed into playing “mammy” roles who appears in the credits of a film called Plantation Memories simply as “The Watermelon Woman.” It’s a movie about movies! “I am a Black lesbian filmmaker who's just beginning,” Cheryl says, and here the thesis of the movie exhumes itself. The text demonstrates a preoccupation with the power of identity as a representational strategy through imagery and insists on its existence, the Black lesbian gaze resisting hiddenness behind the camera and crafting a visible narrative powered by the excavation of archival memory, the straddling of truth and representations of truth, of real and imagined. Dunye’s filmmaking mirrors her own life while the fictionalized version of herself seeks her own image in the black-and-white static of footage nearly lost to history. The Watermelon Woman chronicles the myriad of interconnected dynamics between art and real life–its awareness of the ways it is speaking about and to itself is demonstratively pointed, with Cheryl often speaking directly to the camera about her project and desire to tell Fae’s story.

Fae Richards, the eponymous Watermelon Woman, symbolizes the Black queer archive that future generations of Black queer filmmakers like Cheryl strive to hold within their canon, and as Cheryl interviews subjects for her documentary on Fae and digs through archives she finds proof not only of Fae’s existence but of her queerness¹. She discovers that Martha Page, the white director of Plantation Memories, and Fae were in a relationship, all the while navigating her own dating life, getting entangled with a white video store patron named Diana, much to her best friend Tamara’s dismay. The ways Cheryl’s relationship with Diana parallels Fae and Martha’s excavates the possibilities and challenges of “race relations” within queerness and the ways white lesbianism often possesses an objectifying curiosity with Blackness. The film’s theoretical standpoint as a piece of media that presents a representational theory of Black queerness pointing out gaping holes in the so-called canon is made imminent by some of its casting choices–cultural critic and infamous haver of weird opinions Camille Paglia appears as a parody of herself and a mouthpiece for white feminist film theory offering a misguided take on the “mammy” sterotype, and love interest Diana is played by Guinevere Turner, cowriter and star of the 1994 lesbian film Go Fish. The Watermelon Woman theorizes that sexuality and race are mutually constitutive and through the production and reception of representational imagery this interrelation is complicated by the relationship between the creator and the recipient of an image–Cheryl is a lover of film as much as she is a filmmaker and a large portion of her desire to tell stories about the complexity of being a Black woman who is many things at once comes from her desire to consume these stories.

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” bifurcates queer imagery into “positive” and “negative,” necessarily locating “butch” as a visual identity located in media representations in one of two pathologies². Butchness in film is often leveraged to be emblematic of non-normative female sexuality in a way that is easily visually understood, and as a result, butch lesbians in film have more often than not functioned to be objects rather than subjects of inquiry. Halberstam posits that the debate around positive and negative images often returns to early feminist film criticism calling for “positive representations,” categorically rejecting depictions that could be received in their full complexity as anything other than “good.” Halberstam complicates the idea of a positive image by postulating that this desire for queer imagery imbedded with messaging that campaigns for itself places “the onus of queering cinema squarely on the production rather than the reception of images.” The Watermelon Woman explores how cinema is queered both through the production and reception of images; Cheryl watches Plantation Memories for the first time, she reads the queerness in it and it becomes a queer text because of her viewing, then when it is revealed that The Watermelon Woman and the film’s white director were in a relationship, her read is validated. Cheryl’s onscreen presence as a butch lesbian is overtly queer and her and Tamara’s open discussion of lesbianism as well as an intimate sex scene between Cheryl and Diana underscore this film’s goal of moving beyond the implicit in representation, further informing the lesbian lens with with Cheryl uses to analyze and interpret films like Plantation Memories.

Plantation Memories is not a real film, but it might as well be as it represents the startling politics of race films of its time where the white Scarlet O’Hara-type starlet weeps in the arms of the nurturing Black woman with such vigor that it’s hard not to believe in its existence. The consequence of the effects films like it produced continue to be felt in strategies of representation and Fae Richards does not represent an easily “positive” image of queerness–instead occupying a space in the troubling tradition of the racialized dominant images of Black women in film–yet Cheryl recognizes herself in Fae’s performance partially because it is so fraught. She identifies in her relationship with Diana a similar dynamic to Fae Richards and Martha Page, who only cast her lover in highly stereotyped and racially singular roles, where her lesbianism and Blackness are at slight odds with one another when in a relationship with a white lesbian who can relate to her based on only one of those central tenets and displays a voyeuristic and ultimately isolating interest in the other one. The Watermelon Woman argues for complexity beyond “positive” and “negative” imagery and constructs a Foucauldian reverse discourse where negative imagery can be positively productive when viewed critically and rethought. The film invests in the prospect that art can be a two-way conversation and that by beholding representational images, we project our possibilities onto it. The image on the screen dims and the reflection of the audience is left peering back at itself--Dunye holds onto this moment and treats it with tenderness, imbuing this empty space with hope.

@theuncannyprofessoro

Ratnarajah, Anoushka. “Indisputably Real: Cheryl Dunye’s the Watermelon Woman.” Out On Screen, August 6, 2021. https://outonscreen.com/blog/2020/news/indisputably-real-cheryl-dunyes-the-watermelon-woman/.

Halberstam, Jack. Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film" In Female Masculinity, 175-230. New York, USA: Duke University Press, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822378112-008

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

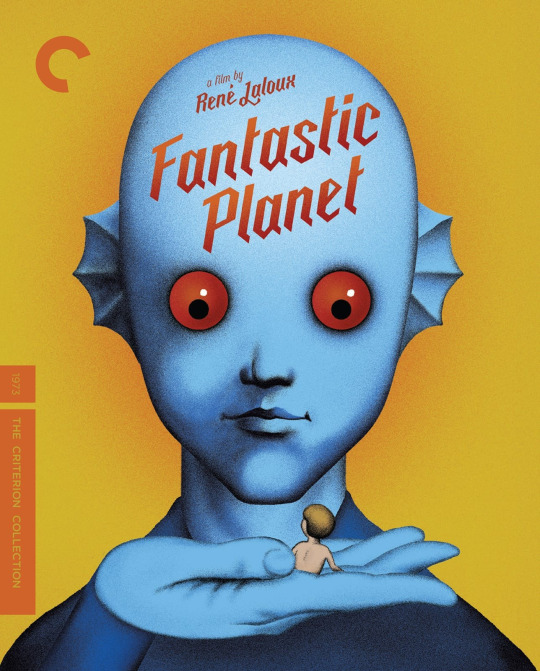

La Planète Sauvage (1973) Race in the Imaginary

René Laloux’s La Planète Sauvage (1973), an experimental animated science fiction art film, is as strange as it is dense with implications. The politically charged dissonance of psychedelia combined with the film’s Dali-esque surreal cutout stop-motion animation universe, realized by French avant-garde artist Roland Topor, has solidified this film as a seminal work of animation and a cult science fiction feature. The film is set in the hallucinatory landscape of the planet Ygam, where gargantuan blue humanoid creatures called Draags who rule the planet enslave humans (called Oms–a play on the French homme)--Terr, an Om who has been kept as a pet since Traag children killed his mother in his infancy escapes from his child captor and bands together with a band of radical escaped Oms to resist the Draag regime and impending genocide. The film is markedly allegorical for its use of imagined alienness to establish otherness and marginalization, and the techniques the Draag use to subordinate the Oms evoke historically significant racist discriminatory practices. Simply, it feels like a movie that is bluntly about something beyond what it appears to be, and the slight heavy-handedness of its messaging reifies its goal of engaging in racial discourse.

The racial politics of Fantastic Planet are strange in that the broadness of the trenchant sociopolitical commentary imminent in the dynamic between oppressor and oppressed has led critics to draw comparisons between the plot and the narrative around “animal rights” and the (mis)treatment of domesticated animals, yet the human-ness stitched into the film’s fabric positions it as a text specifically interested in the ways humans create divisions among themselves. The Draags and the Oms, despite their vast difference in physical size, do resemble one another and take on different forms of the corporality of a human being, and for this reason and many others, Fantastic Planet seems to be a film about how we could recognize ourselves in one another and still splinter into factions and enforce senseless violent domination.

Terr’s captor, a girl named Tiwa, has given him a collar to control him as he attends “school” with her, which involves her wearing a headset that transmits facts into her brain, and a defect in his collar inadvertently allows him to learn the same knowledge as Terr, knowledge he ends up using to save the Oms. Intelligence is the gateway to capital in Ygam and the Draags are highly intellectualized beings who pride themselves on their inborn wisdom and biological superiority that allows them to far outdo the meager Oms in their knowledge–the film comments on the complications of the racialized bioessentialist understanding of knowledge that would posit that being smart, and subsequently having value, is a fixed innate biological trait. The Oms navigate the world through cunning, outwitting the Draags practically in ways they might fail to do so intellectually and the Draags and Oms counter one another in the film on what “counts” as knowledge: the Draags favor transcendental meditative practices that imbue them with highly complex perspicuity, whereas the Oms argue that their knowledge is more useful for the ways it enables them to survive despite their circumstances. The Oms are made alien not only through their physical inferiority but also because they exist in a society that was not built for them. Fantastic Planet depicts an idea of home that is stringent upon exclusivity and requires technical superiority to belong; shoring up racial politics, Fantastic Planet deploys a social constructionist standpoint that colors these divisions as the products of structural forces benefitting only those who erected them.

youtube

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I couldn't agree more that Whale Rider argues for the necessity of both tradition and evolution--the ways they coexist in this movie and in the end are proven to be capable of working together are incredibly thoughtful and poignant and one of the crowning achievements of Whale Rider.

Whale Rider

The film Whale Rider, by Niki Caro, explores the theme of tradition clashing with modernity through the experience of Paikea, a young Maori girl. Paikea is eager to learn Maori tradition yet is left out of a large part of it because she is a girl. Her innate curiosity to enact tradition is a disgrace to tradition itself according to her grandfather Koro. Despite her love and respect for him, Paikea struggles against his rigid adherence to tradition and his reluctance to recognize her potential simply becuase of her gender. The film highlights the evolving dynamics of the family structure as it grapples with generational differences and the desire for continuity. The conflicts in the film arise becuase of certain gender expectations being placed on each of the characters that they fail to meet. "Whale Rider" suggests that while tradition is essential for cultural identity and continuity, there is room for evolution and adaptation. It celebrates the idea that qualities of leadership and strength can be found in unexpected places, transcending gender norms and challenging established traditions. The movie encourages a more inclusive and open-minded approach to tradition that can involve every generation, preserving cultural heratige while also adapting and evolving.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You make a really interesting point about the significance of Paikea's age and status as a child and how it is relevant to her relationship to the past. The film's central conflict is that she is a girl, yet her being a child further implicates how she is gendered--she represents the entry into a new epoch for her tribe, which is made harder by the fact that she struggles to gain credibility and respect not only as a girl but as a child.

Whale Rider Viewing Response

In Whale Rider (2002), Paikea is a young Maori girl who has to fight to prove her ability when her twin brother, who has been selected to be the next chief of their New Zealand tribe, dies at birth. Paikea is a self-assured, confident, wise young girl who is determined to convince her grandfather to open his mind to the rigid, sexist customs he abides by. As Belinda du Plooy writes in her piece, "Anthropocene terror in two girl-centred narratives: The leitmotifs of mythological time, colonisation and monstrosity in the films Whale Rider and Moana," Paikea's gender and age place her as a symbol of hope and change in the film. Du Plooy describes film as a medium for "speaking and listening to the stories of others as part of both an ethical response to the narratives of the past and a moral responsibility to engage the present." I think more than ever, we see children as a necessary piece of the discourse surrounding the past and how we should be evolving and changing. They "embody the projected dreams, desires and commitment of a society's obligations to the future." I think that an important piece of Paikea's character, identity, and activism is her age. If her brother had been born, he would have been assumed as the next chief and he, nor anyone else, would have to question that. Because Paikea is a girl, she is forced to think about and challenge these things as a child. This is representative of how necessary it is that we listen to and take seriously the children who are going to break the boundaries of where they are traditionally and systematically placed in society, because they have no other choice but to resist. Paikea represents hope and demands she be listened to because if she doesn't, how is anyone to move forward?

@theuncannyprofessoro

1 note

·

View note

Text

Whale Rider viewing response

Niki Caro's Whale Rider, a 2002 New Zealand drama film based on a book by the same name, explores what tradition and hope can offer one another. The character of Paikea, whose traditional grandfather Koro is convinced brought misfortune to the tribe since her birth, has within her a deep-seated generational memory, an ancestral force that compels her at the film's climax to approach the stranded alpha whale and ride it back into the ocean as the founder of her patrilineal tribe once did. She engages with tradition interestingly here, reaching through her lineage and pulling herself towards a mythological coming-home that empowers her to entrench herself in her tribe, while simultenously reforming this tradition and sacralizing the new. The film is invested in Pai's scrutiny of tradition as she watches Koro teach the village boys how to use a taiaha, hoping to train a new leader, and secretly learns to use it herself. She is inventive and determined, and with ease she conquers the pillars of tradition, holding past and future in each of her hands, thoughtfully eschewing what doesn't serve her and still clutching onto some veneration of the past. She is frustrated with Koro's refusal to accept her as the rightful future leader she knows herself to be because she feels this ancestral memory within her that she is meant to lead her tribe--Whale Rider tells a story where memory is magic, and this magic is not so simple as to be a nonsensical calling from an ethereal plane but is instead the throughline connecting Pai to those who came before her. Her memories are, in a way, not her own, and these instincts motor her through the difficulties of repeatedly being disallowed from participating in the cultural practices that would enter her into leadership. Her journey through indigenous temporality and ancestral memory calls her to lead in the end and the ways she navigates this calling, with a balance of stoicism and childlike earnestness, are demonstrative of the forces within her too vast and deep-seated to be anything other than her ancestors working through and for her. Pai is knee-deep in the waters of past, present, and future all at once.

@theuncannyprofessoro

1 note

·

View note

Text

I'm glad you gave Sweet Bean another shot! I couldn't agree more about the lighting of the film. It imbues it with an intimacy I found really interesting and something I often find necessary for a movie as character-driven as this one--the most important scenes are the ones where very little might be actually happening, and we instead are meant to sit and watch these people go through the motions and embark on their journeys through food.

Sweet Bean? More like Sweetie Pie

I watched Sweet Bean for the first time a few years ago and thought I didn’t like it, but boy was I mistaken!! Something I was really taken aback by during this screening was the lighting – every scene was beautifully lit and perfectly set the tone. In particular, the scene where Tokue makes an in the shop for the first time. In his article “Art with the Right Ingredients: An and the Films of Naomi Kawase,” Anthony Carew writes that “the preparation of the red bean paste is lovingly shot, and given mythical credence,” which is emphasized by the lighting (50). As a borderline religious experience, when Tokue peeks into the pot or as Sentaro looks on, both are darkly lit for similar reasons: Tokue is communicating with the family of azuki beans while Sentaro is seeing Tokue in her mysterious, magical element of making perfect an. I believe that this scene is the beginning of bridging the generational gap that has been insurmountable for so many people in Tokue’s life. In a dark, private, beautifully revealing moment.

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love your observation that Tokue treats the adzuki "as if they had a life of their own." Her gentleness in this film is so compelling, especially when juxtaposed with the harshness she endures from the world around her as a result of her condition. This film takes its time in the scenes where food is handled, and the love present in the ways this food is prepared is one of my favorite parts of Sweet Bean.

Making Red Bean Paste in Sweet Bean

The scene of Tokue first teaching Sentaro how to properly make red bean paste is a wonderful depiction of traditions being lovingly passed down and connections being made. As Carew writes, “An is essentially a shrine to ‘slow food’, to time-won wisdoms, and to the traditions being lost to today’s hyper-capitalist, factory-model food industry” (3). Viewers are able to see how Tokue treats the adzuki beans with great care and as if they had a life of their own. Tokue’s long and enduring process pays off and proves that homemade goods made with love are much better than artificial bulk products. The labor put into the bean past is evident in its taste and the customers’ love of it. The red bean paste and the process done to make it connects Tokue and Sentaro, and later Wakana, together as they lovingly make dorayaki together and peacefully enjoy the small shop’s success. The act of making red bean paste serves as a healing process for the three and shows the multiple values of traditions.

@theuncannyprofessoro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sweet Bean Viewing Response

Sweet Bean, a 2015 Japanese drama film directed by Naomi Kawase follows a man named Sentaro who owns a dorayaki shop in Tokyo and ends up hiring an elderly woman, Tokue, to make the bean paste. This film is slow and sweet, yet ends up taking a sudden departure into sadness--the crux of this melancholy, Tokue's life in the sanatorium and eventual death, takes place entirely off-screen. Kawase insists that this is a movie about food, shots lingering on the batter frying on the griddle, and careful visual attention paid to the bean paste, and doesn't stray from this mission. The film's tone is understated and its movement is intimate, framing the actors closely and allowing their faces to subtly convey the ebbs and flows of a hard day's work and the satisfaction of creating something different.

Tokue's secret struggle, her battle with leprosy adds an interesting depth to the film, but one I struggled to engage with for the ways Kawase leverages it for a message about tolerance rather than a tenet of one of her central characters--it feels sudden and the audience is left wanting to understand more about her when all of a sudden she disappears from the screen and Sentaro, a character who is decidedly less compelling than Tokue is left to pick up the pieces and anchor the film.

@theuncannyprofessoro

1 note

·

View note

Text

Laughing Through Color: Alice Wu's Saving Face (2004)

Saving Face is a vastly underrated 2004 lesbian rom-com about Wilhelmina (AKA Wil), a young closeted Chinese-American surgeon whose mother Hwei-Lan, played by the inimitable Joan Chen of Twin Peaks fame, continues to try to set her up with Chinese men at community events, one of which leads her to the magnetic Vivian Shing, a dancer whose father happens to be Wil's boss. An unmarried 48-year-old widow, Hwei-Lan unexpectedly gets pregnant, is subsequently shunned by her community, and moves in with Wil all while refusing to divulge the identity of her child's father to anyone, including Wil. She hides herself from Wil, who hides herself in return as Vivian forces her to grapple with queerness in public vs. private. The mother and daughter both struggle with the ways their sexualities are on display, for Wil on the axis of queerness and for Hwei-Lan as a pregnant unmarried person and are afraid of how the cultural norms they transgress infiltrate their relationship with each other and the world around them, a fact that ultimately helps them relate to each other more.

It was the feature debut for Alice Wu, a Taiwanese-American lesbian director, and one of the most interesting things about it for me is how it explores Wil's queerness as a parallel to her mother's journey and the ways the two work against gendered and cultured expectations alongside each other. This movie is smart, sexy, funny, and thoughtful and demonstrates a possibility for the rom-com genre to traverse nuanced depths of love and relationships and how culture imbues them with questions that prove so difficult to answer. It doesn't rush to answer these questions or present them as simple dilemmas constructed as mechanisms to thicken the plot but positions them as part of the architecture of love. Saving Face is invested in how many things can be true at once. What if queerness could be relatable beyond its variable boundaries and could help articulate the disillusion of being marginalized by your own community? Hwei-Lan's journey with her daughter's sexuality prods at this, wades around in its fullness--she is at once in and out of her culture, held by its comforts and shunned by its rigidity, but when confronted with this complication in Wil she sees so much familiarity reflected back at her.

Wil's relationship with her mother starts to affect her budding romance with Vivian who, unlike Wil, is openly gay. Vivian is pursuing contemporary dance against the wishes of her father, who wants for her to continue in traditional ballet--at the nexus of this story is the conflict between individual desire and tradition, and the added layer of queerness implicates this conflict and creates in the characters differently complicated relationships with authenticity. Vivian transcends her ethnic origins in her espousal of American values, especially concerning individual freedoms, and Wil's reluctance to detach from these origins (and subsequently alienate her mother) starts to impact their relationship. Wil is afraid to kiss Vivian in public but loves her freely in private; Saving Face understands the ability to move through public spaces as yourself as a culturally specific phenomenon and presents the stories of people who never had to think about it so much as they do at this moment, who try to make it matter less but when it comes crashing down on them, discover how badly it is they wish to be seen.

Alice Wu sought specifically to make a movie by and for Asian-American queer people, repeatedly rejecting studio's pleas to cast a major white actress in one or both of the leading roles and the film having an entirely Asian-American cast is an significant diversion from the typical trajectory of Hollywood rom-coms--Kaklamanidou's “Romantic Comedy and the ‘Other’: Race, Ethnicity, and the Transcendental Star" points out that many people of color in the rom-com genre, Will Smith in Hitch being one achieve stardom and success through the ways they shore up comfortable, easily digestible and markedly neutral characters who happen to be people of color without isolating white audiences, wherein box office success is entrusted. Saving Face, however, demonstrates a lack of interest in mainstream success and is interestingly also somewhat lacking from the queer canon; it occupies a noticeably niche space in the realm of queer movies insofar that its mainstream success was limited but, unlike other "before-its-time" movies ascribed with queer cult status such as Jennifer's Body, didn't necessarily circle back around to audiences today. The lack of whiteness in this film is no doubt a salient causal factor in this lack of rebirth--while being funny, it also demonstrates a commitment to telling arguably a serious story, and the film doesn't necessitate a "campy" read as much as other retroactively added to the queer canon.

youtube

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is such an interesting and smart observation! I couldn't agree more that the omnipresence of transportation in this movie suggests the possibility for movement toward the unknown, but the characters instead choose to stay in place. Your point that the scene where they get caught in the rain and have to stop their journey is a fantastic connection to this theme and one I hadn't thought about.

35 shots of rum analysis

Something I really loved about "35 Shots of Rum" was the use of transportation throughout the film. Lionel is a train conductor so we see him in scenes in the tracks or on the train a lot of the time, but also the use of seeing all the characters in buses and cars. While transportation moves people from one place to another, it is clear that a lot of these characters feel stuck. In James S. Williams' "Romancing the Father in Claire Denis's 35 Shots of Rum", he writes about "the poetic images of passage and transience." I think this is clear in the scene where Lionel and Rene are sitting on the bus after Rene's retirement party. Rene is very depressed and says that he can't believe he still has so much life to live. It is clear that he feels stuck. But, he is on the bus, surrounded by people from his now former job, on the way home. It is a powerful juxtaposition to feel stuck when on a bus and also when you were once a train conductor - one could argue you could go anywhere. But, the use of the public transportation in this film is not to show how characters could go anywhere, but how even with accessibility to the outside world, they choose to stay where they are, comfortable. This is also portrayed when the four characters start driving and the storm starts: when they try to break out of that comfort, they are faced with the reality that they are meant to stay stagnant.

@theuncannyprofessoro

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is so significant to the story that, as you point out, the two central characters of the film whose relationship is the lynchpin of its trajectory hardly speak to one another at all. It almost seems like their domestic comfort allows them to settle into a routine where they assume so much about the other and don't feel a need to communicate. This is undoubtedly a catalyst for their relationship changing, without conflict, because this unspoken-ness cannot hold all of their desires and the things they assume about one another might not be as true as they believe and they've lived with these preconceived notions of each other for so long.

"35 Shots of Rum" Viewing Response

"35 Shots of Rum" tells the intimate story of a father-daughter relationship strained by the daughters romantic involvement with a neighbor. The film's slow pacing and subtle drama creates an uncomfortable realness in the tension between characters. In "Romancing the Father in Claire Denis's 35 Shots of Rum" James T. Williams highlights the speed and swiftness with which the film moves through death, grief, change, and anger. The characters speak softly to one another, Lionel and Josephine, whose relationship is central to the narrative, often say nothing to each other at all. Their relationship is mostly narrated through their expressions, physical contact with one another, and their coexistence in mundane activities like cooking. As Josephine forms her relationship with Noé and decides that she wants to be with him, the space that her and her father occupy together changes. Although there is very little outright conflict or drama, we feel the weight of the shift in their relationship.

@theuncannyprofessoro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

35 Shots of Rum and the little things

Claire Denis' 35 Shots of Rum (2008), set in contemporary France, paints a sedate picture of human relationships and the way their minutia means the world. Lionel and Josephine are father and daughter and Lionel's devotion to fatherhood causes Josephine to put herself aside sometimes to protect his feelings. He needs her to need him, and when she begins to express interest in Noé, he must come to terms with this. Denis is keenly invested in the small things: a covert glance, a cup of coffee placed on a saucer. Gabrielle, a cab driver who lives in the same building as Lionel and Josephine, shows interest in Lionel, who seems uninterested in anything beyond casual acquaintanceship with anyone except his daughter. The film takes its time and Agnès Godard's moody cinematography helps the audience live in its world--these characters are interconnected and long for more, sure, but they're in no rush to name or finalize these connections. Gabrielle clearly imagines a possibility of herself fitting into Lionel and Josephine's domesticity, but she doesn't hurry to facilitate this and instead lets it be what it is. Denis' storytelling allows these people to drift towards one another, struggling with the ebbs and flows of the limits of their own comfort, instead of pushing them towards one another. Lionel views Rene, his depressed retiring coworker, as a looming specter of what he could be if he fails to have a purpose and upon finding him at his demise, this warning seems final. Denis' narrative structure requires you to pay rapt attention for the way that, at first glance, not much seems to be happening. The lived-in character of the film demonstrates faith in its audience to project their own feelings of the beauty in letting relationships crash on the shore onto the story.

@theuncannyprofessoro

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I couldn’t agree more that the kiss felt like a step back. It felt like she was building towards so much, and the conclusion where she and the coach end up together felt so regressive. It made me think about why it is that they felt this plot line needed to happen—I suspect that in order to market this movie, there had to be a central romance, yet the movie’s ambitions as a commentary on cross-cultural dialogue impacted how they approached it.

Bend it Like Beckham Viewing Response

In Bend it Like Beckham, Jess is constantly having to fight against the assumptions that are being made about her based on her love for soccer. Her family fears that the fact that she wants to play soccer professionally means that she is less of a woman and means that she will have trouble finding a man to marry. They also see it as a rebellion generally and worry that it is the beginning of the end of Jess abiding by their rules and expectations. We see this kind of fear and judgement coming from Jules' family as well. Jules' mom says that boys won't like Jules because she dresses more masculine and accuses Jess and Jules of being in a romantic relationship. Whether or not there is a queer undertone to the film, the sheer fact that Jess and Jules want to play soccer is completely unrepresentative of their sexuality, gender expression, or ability to "find a man." Ultimately, Jess's parents see how happy it makes her and allows her to go with Jules to play soccer professionally in the US. This feels like such a freeing moment for Jess. She will be able to begin the process of finding herself when she is free from her parents expectations. That is why, to me, the ending being her kissing the coach for the first time was really disappointing. It felt like a step back towards the life she was living and the things that were holding her back. We see the coach playing with Jess's dad in the ending montage, suggesting that maybe he has found a place in her family and will be there for her when she gets back. Her relationship with the coach feels like a regression to the things that kept her silent and lying all the time. She had an opportunity to be completely free and start over with her best friend, but ultimately the movie had to end with her finally getting the man, rather than just living out her dreams.

@theuncannyprofessoro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is so interesting when you consider the role womens' sports have compared to men's sports--I have to imagine this film would be so different if Jess was a boy, whose passion for sports might be regarded with more seriousness! Part of her parents' struggle to support her sport is its masculinity and their worry about people's perception of their family being impacted by having an athletic daughter is not unfounded.

Bend It Like Beckham

Throughout Bend It Like Beckham, female soccer is not regarded as serious by men, limiting the ability for Jess and Jules to play. Even their coach says he applied for a promotion to be assistant coach on a mens team. While men who play soccer are seen as strong, women are regarded as too masculine, and therefore undesirable. Jess and Jules are assumed to be in a gay relationship twice, showing how the closeness of their friendship is regarded as homosexual. Because they play soccer, they are regarded as masculine and therefore gay. Jules mother even says that playing soccer turned Jules gay. This shows how gender expectations are associated with sexuality, pushing Jess and Jules to appear more feminine. Both Jess and Jules are impacted by their parents' perceptions of what girls should be acting like. They disapprove of their daughters playing soccer because they fear it will impede their social desirability and attractability to men. Jess’ parents assume that because they face prejudice, they need to protect their children and make sure they are afforded with the most opportunities possible. Once her father sees that she has a talent at soccer, he lets her pursue it, showing how this film is more than a reductive representation of Indian immigrants. Mary Chacko writes in her analysis of Bend It Like Beckham that the title of this film is a “ metaphor for the ways in which girls like Jess attempt to bend the rules prescribed by their cultural backgrounds to achieve their goal”. Jess is able to subvert cultural and gendered norms through her talent and dedication, showing she is more than a stereotype of girls or of Indians. She attends both her sisters wedding and her soccer final on the same day, representing her ability to fulfill her cultural expectations and also play soccer.

10 notes

·

View notes